Abstract

Background

Self-management is an important component of care for patients or consumers (henceforth termed patients) with chronic conditions. Research shows that patients view guidelines as potential sources of self-management support. However, few guidelines provide such support. The primary purpose of this study was to characterize effective types of self-management interventions that could be packaged as resources in (i.e., appendices) or with guidelines (i.e., accompanying products).

Methods

We conducted a meta-review of systematic reviews that evaluated self-management interventions. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library were searched from 2005 to 2014 for English language systematic reviews. Data were extracted on study characteristics, intervention (content, delivery, duration, personnel, single or multifaceted), and outcomes. Interventions were characterized by the type of component for different domains (inform, activate, collaborate). Summary statistics were used to report the characteristics, frequency, and impact of the types of self-management components. A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) was used to assess the methodological quality of included reviews.

Results

Seventy-seven studies were included (14 low, 44 moderate, 18 high risk of bias). Reviews addressed numerous clinical topics, most frequently diabetes (23, 30 %). Fifty-four focused on single (38 educational, 16 self-directed) and 21 on multifaceted interventions. Support for collaboration with providers was the least frequently used form of self-management. Most conditions featured multiple types of self-management components. The most frequently occurring type of self-management component across all studies was lifestyle advice (72 %), followed by psychological strategies (69 %), and information about the condition (49 %). In most reviews, the intervention both informed and activated patients (57, 76 %). Among the reviews that achieved positive results, 83 % of interventions involved activation alone, 94 % in combination with information, and 95 % in combination with information and collaboration. No trends in the characteristics and impact of self-management by condition were observed.

Conclusions

This study revealed numerous opportunities for enhancing guidelines with resources for both patients and providers to support self-management. This includes single resources that provide information and/or prompt activation. Further research is needed to more firmly establish the statistical association between the characteristics of self-management support and outcomes; and to and optimize the design of self-management resources that are included in or with guidelines, in particular, resources that prompt collaboration with providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Governments, professional societies, foundations, academic groups, and other organizations worldwide develop guidelines which translate scientific research findings into recommendations that have the potential to enhance health care quality and outcomes [1]. Guidelines are viewed as a foundation for health care planning, delivery, evaluation, and quality improvement [2]. However, the inconsistent use of guidelines has been referred to as a crisis, leading to heterogeneity in clinical practice, over- or underuse of beneficial therapies, preventable harm, suboptimal patient outcomes or experiences, and inefficient use of resources [3, 4]. Efforts to tailor a wide variety of guideline implementation strategies have achieved positive yet modest results. Thus further research is required to understand how guideline implementation can be optimized [5, 6].

Interviews with health care professionals revealed that they struggled to interpret and apply guidelines, and that they desired tools that would facilitate guideline implementation [7]. Systematic reviews show that implementation tools such as guideline summaries, algorithms, point-of-care checklists, and health status reminders enhanced compliance with guideline recommendations [8–10]. Experts have also advocated for the development of guideline-based implementation tools that could be used by patients and providers to clarify the goals of care, understand the underlying evidence, assess the risks and benefits of treatment options, and enable informed decision-making [3, 4]. In other research, we revealed that few guidelines published between 1980 and 2013 offered information or tools to support implementation [11]. We also learned that organizations generating guidelines desired guidance for developing implementation tools [12] given that current guideline development instructional manuals lacked such instructions [13, 14]. We then engaged the international guideline community to produce a framework and considerations with which to assess and adapt existing or develop new guideline implementation tools [15, 16].

Historically, health care professionals were considered to be the primary users of guidelines. Now, it is well-recognized that patients or consumers (henceforth referred to collectively as patients) should be involved in guideline development and are key users of guidelines [17–19]. An emphasis on patient-centered care has also prompted the development of resources to engage patients in their own health care [20–22], and research has optimized the format and content of evidence summaries for the public [23]. So far, little research has examined how to implement patient-oriented tools such as lay language summaries or decision aids into practice [24], and only one study investigated how guidelines can be used as a vehicle for disseminating such patient-oriented implementation tools [25]. In the previous research, we analyzed the content of guidelines and found that 50 % provided information to educate or engage patients [26]. Of these, five guidelines provided information to help clinicians discuss relevant issues with patients, two included information sheets for patients, and seven provided contact information (phone number or web site) where information for patients could be obtained. A systematic review found that patients and members of the public viewed guidelines as sources of health information, support for informed decision-making, and resources to manage their own care but were uncertain about how to find, assess, and use guidelines [27]. This may highlight an opportunity for guideline developers to enhance the implementability of their guidelines by including patient-oriented tools and for providers to share guidelines and associated patient-oriented tools with patients at the point of care. This may improve the adoption and impact of guidelines.

The prevalence of chronic disease is increasing worldwide, and the challenge of addressing the needs of patients with one or more chronic conditions is well-recognized [28]. Self-management has been commonly defined as “the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions” and self-management support as “the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions by health care staff to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support” [29]. It is distinguished from shared decision-making which involves deliberation between patients and providers about the risks and benefits of health care options to arrive at a mutually agreeable decision about the best course of action for that patient [29]. Self-management is viewed as a complementary to medical care—it is an ongoing process that involves (1) interaction with health care professionals to (2) provide patients with information and education about their condition, its clinical management, options for self-care and what to expect, and activities traditionally provided by health care professionals and, (3) above and beyond that, equip patients with strategies and tools to help them implement and sustain behaviors to cope with their condition and optimize quality of life [30]. A meta-review of self-management support by Taylor et al. found that program components ranged along a spectrum from simple summaries of disease-specific information to multifaceted interventions [31]. However, the review did not identify one or more components as crucial [31]. Effectiveness was variable across interventions and conditions. For example, action plans were beneficial for asthma management while self-monitoring was beneficial for hypertension management. Educational information was a core component of all self-management interventions evaluated in 102 systematic reviews, including 969 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Qualitative studies included in the meta-review revealed that effectiveness may be associated with good communication with providers at the point of care about self-management.

An increasing number of patients with chronic conditions may require and benefit from self-management, and self-management may be an intervention best introduced by providers at the point of care. It may be possible for guidelines to provide patients and providers with resources that enable the interactive, educational, and supportive domains of self-management. First, we need to understand the components of self-management interventions that are both effective and of a nature such that they could be included as resources in print or electronic versions of guidelines. The primary purpose of this study was to systematically review published research on self-management to describe the self-management components that have been evaluated as effective and could potentially be packaged in (i.e., as appendices) or with guidelines (i.e., as accompanying products) for use by patients and physicians to promote discussions about and the uptake of self-management. A secondary purpose was to assess the effectiveness of single versus multifaceted types of self-management interventions, as this has implications for the resources required to develop and include one or more self-management components in or with guidelines. Ultimately, the inclusion of such resources in guidelines may improve the implementation and integration of self-management into care delivery and self-care and, by enhancing the implementability of guidelines, lead to greater adoption of guidelines and associated beneficial outcomes.

Methods

Approach

Given the large number of published systematic reviews on self-management, a meta-review of systematic reviews on the impact of self-management programs was conducted using standard systematic review methods [32]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria guided the conduct and reporting of the review [33]. Data were publicly available so institutional review board approval was not necessary. A protocol for this review was not registered. Data extracted from eligible systematic reviews describing self-management interventions were thematically analyzed to categorize them according to type of self-management components and assess observable patterns of association between type of self-management components and beneficial outcomes reported by eligible studies.

Scoping

To plan for the full-scale review, a preliminary scan of relevant literature was undertaken by assessing the nature of eligible studies included in the Taylor et al. meta-review [31]. This refined the objectives of the review, leading to the development of a population, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes (PICO) statement and contributed to the development of search parameters and screening criteria. The Population of interest was adult patients or consumers aged 18 years and older with any chronic health condition including communicable and non-communicable diseases with no definite cure. The Intervention of interest was self-management interventions delivered in any format, potentially referred to instead as self-care, self-monitoring, or self-help interventions. Self-management interventions were comprised at minimum of an informational or educational component and potentially additional supportive (behavioral, educational, psychological, clinical) components to encourage people to take an active role in their own health and better manage the condition itself and their overall well-being [31]. Relevant study Comparisons included patients with and without exposure to self-management interventions, or before or after exposure to self-management interventions, or patients receiving different types of self-management interventions, or comparison of any type of self-management intervention with any type of alternative intervention that was meant to address the same health condition issues as the self-management intervention. Self-management interventions are usually targeted at maintaining or improving life with the condition, rather than improving the condition itself; therefore, Outcomes of interest included any functional outcomes that were reported by the study, including but not limited to adherence to medical care, physiological function, overall well-being, return to daily living, pain, social or psychological factors, or adoption of new activities or behaviors, measured clinically, or with instruments, questionnaires, or interviews.

Searching

MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and CINAHL were searched in February 2015 for studies published from January 1, 2005 to that date which evaluated self-management interventions. A 10-year time span was used to capture the components of self-management interventions developed more recently, thereby enabling a current-day description of informational or educational self-management components that could accompany guidelines. To ensure that our meta-review was comprehensive, we also applied our screening criteria to review the 102 systematic reviews included in the Taylor et al. meta-review [31] which included systematic reviews of RCTs published from January 1993 to June 2012 (as reported by authors). Our meta-review updates and expands on the meta-review conducted by Taylor et al. [31] by including nearly two additional years of published systematic reviews and systematic reviews that may have included study designs other than RCTs. The search strategy was purposefully broad to be as inclusive as possible and included both Medical Subject Headings and keywords (Additional file 1). Searches were limited to English language to avoid the cost of translation and expedite completion of the review.

Screening

Titles and abstracts of search results were reviewed independently by ARG and a research assistant following a pilot test during which they independently screened the first 100 results, then compared and discussed their selections to establish a shared understanding of the screening criteria. All items selected by at least one reviewer were retrieved for further assessment. If more than one publication described a single study, the most recent or complete publication was included. Selection criteria included systematic reviews or meta-analyses that described the impact of self-management interventions meeting the criteria specified in the abovementioned PICO statement. As search results were reviewed, selection criteria were expanded to specify studies that were not eligible. Studies were excluded if they focused on (1) clinical treatment; (2) individuals that did not have a chronic condition but temporarily required self-monitoring, for example, as part of rehabilitation after surgery or an accident; (3) contextual or environmental conditions that may influence or moderate the impact of self-management, for example, the role of family; (4) information-seeking patterns among patients or the well public; (5) promotion of self-care for the elderly without any underlying disease or as a means of preventing a disease; (6) self-management interventions with no educational or informational component, for example, exercise only; or (7) barriers to self-management. Guidelines as a publication type, protocols, proceedings, abstracts, letters, editorials, or commentaries were not eligible.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed to collect information on study design (number/type of eligible studies), disease or condition, number and type of participants, methodological assessment, intervention details (content, delivery mode, frequency and duration, audience, personnel), and findings. ARG and a research assistant pilot-tested the form on three articles through four iterations until data extraction was consistent. The research assistant proceeded to extract data from all eligible studies. Extracted data were confirmed independently by RWMV and MW who reviewed each study and edited or added to the extracted data.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of eligible studies was assessed with A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR), for which a score of 0 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 11 represent low, moderate, and high quality, respectively [34]. ARG and the research assistant independently assessed 10 studies, then compared and discussed their findings to achieve a shared understanding of how to apply the criteria, following which the research assistant assessed remaining studies.

Data analysis

Extracted data were summarized to describe the characteristics of eligible studies including years when published, country of first author, the number of included studies and participants, and the quality of included studies if assessed. Interventions were categorized as educational sessions (single or multiple provider and/or lay leader sessions during which information was conveyed to individuals or groups in-person or by virtual means), self-directed guides (print material, computer, Internet, or information technology if more than one electronic delivery mechanism was used), or counseling (brief in-person or virtual interaction during which providers and/or lay leaders provided patients with recommendations, reminders or encouragement). Data were not pooled due to heterogeneity in the study design, nature of interventions, and reported outcomes.

The primary purpose of this review was to describe the components of self-management interventions. To do so, we used a modified version of the taxonomy of self-management components generated by the Taylor et al. meta-review in which we eliminated items pertaining to clinical care or the provision of equipment and retained items that could potentially be included in or with guidelines [31]. The modified taxonomy of components were categorized into three domains adopted from work by Grande et al. [20] corresponding to the interactive, educational, and supportive aspects of self-management: informing—providing knowledge about their condition and an understanding of how to manage it; activating—providing information or tools to prompt action for actively managing the condition and enhancing quality of life; and collaborating—providing information or linkages that lead to interaction with health providers or agencies. Table 1 shows the resulting taxonomy used to describe the components of self-management interventions and provides examples of each. Two authors (RWMV, ARG) independently used thematic analysis to peruse the details of self-management interventions extracted from included studies and categorize them as one or more components. They compared findings and discussed discrepancies to achieve consensus.

The secondary purpose of this review was to assess whether single-component self-management interventions were as effective as multifaceted self-management interventions. Eligible studies were categorized by self-management component (Table 1) and by format of delivery as single- (one of education session, self-directed guide, or counseling) or multifaceted (more than one of these). Given the diversity of conditions, interventions employed, and outcomes reported, we did could not pool and statistically analyze the impact of interventions. Instead, to explore potential trends, outcomes as reported by the authors were categorized as all positive (improved outcomes), all negative (no change or worsening outcomes), or mixed (a blend of improved, no change, or worsening outcomes).

Results

Search results

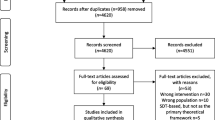

A total of 1001 unique articles were identified by search strategies across all sources of which 882 were excluded based on screening of titles and abstracts, leaving 119 full-text articles to be screened. Of these, 42 were excluded due to study design (7) or lack of details about methods, intervention, or impact (6); focused on prevention (1) or clinical treatment (6), views about, or barriers of self-management (4) did not evaluate the impact of self-management (10) or were based on an intervention that did not include an educational or informational component (9). As a result, 77 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1). Data extracted from each review appear in Additional file 2 [35–111].

Characteristics of eligible studies

Of the 77 eligible reviews, 19 (25.0 %) were conducted in the UK, 18 (23.0 %) in the USA, 10 (13.0 %) in Australia, and 5 (6.5 %) in Canada. Other reviews conducted in Europe (other than the UK) emerged from the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark. The majority of reviews were conducted in the year 2010 or afterwards (70.0 %). The largest proportion of reviews by year published occurred in 2013 (16.9 %). The mean number of studies included in eligible reviews was 23.6 (range 2.0 to 163.0). Eligible reviews addressed a wide range of clinical topics that were categorized as metabolic conditions which were all related to diabetes (23, 29.9 %); musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis and back pain (12, 15.6 %); reviews of a variety of chronic conditions (12, 15.6 %); cardiovascular conditions such as angina, hypertension, heart disease, and stroke (11, 14.3 %); pulmonary conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (7, 9.1 %); other conditions such as cancer pain, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and kidney disease (7, 9.1 %); and mental illness including anxiety and depression (5, 6.5 %).

Quality assessment of eligible studies

Quality assessment found that 14, 44, and 18 studies had a low, moderate, and high risk of bias (Additional file 2).

Characteristics of self-management

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of self-management interventions reported in 75 of 77 eligible reviews that provided sufficient detail to categorize them according to domain, component, and delivery format. Of these, 54 reviews included studies that largely employed single types of interventions (delivery format). These were educational sessions in 38 studies, self-directed guides in 16 reviews of which 14 involved self-directed guides in electronic form (computer or phone application, Internet), one review in print format, and one review in which both electronic and print self-directed guides were offered. A further 21 reviews included studies that offered a variety of single interventions or multifaceted interventions. These included 8 reviews of education, self-directed guides, and counseling; 7 reviews of education and self-directed guides; 4 reviews of education and counseling; and 2 reviews of self-directed guides and counseling.

The majority of reviews included self-management interventions that involved multiple domains (i.e., inform, activate, collaborate) and components. For example, 36 reviews included studies with interventions that provided components to both inform and activate patients, while 21 reviews included studies with interventions that provided components to inform and activate patients and promote collaboration.

Impact of self-management

Table 2 summarizes the reported outcomes of eligible reviews. The majority of reviews reported positive results for all measures reported (47/75, 62.7 %). This included 23 reviews of educational sessions, 10 reviews of self-directed guides, and 14 reviews of multifaceted interventions. Mixed results were reported in 23 reviews (11 education, 5 self-directed, 7 multifaceted), and 5 reviews (4 education, 1 self-directed) failed to show the impact of self-management on reported outcomes.

When outcomes were perused by the type of self-management domain (i.e., inform, activate, collaborate), it appeared that interventions which activated patients may have been associated positive impact. This may have been supplemented by interventions that also informed patients. For example, positive results were achieved in 58.3 % (7/12) of interventions based on activation alone, 66.7 % (24/36) in combination with information, and 57.1 % (12/21) in combination with information and collaboration. If reviews that achieved both positive and mixed results were considered, then 83.3 % (10/12) of interventions based on activation alone, 94.4 % (34/36) in combination with information, and 95.2 % (20/21) in combination with information and collaboration were successful. This apparent trend was observed across educational, self-directed, and multifaceted interventions. Positive results were also achieved in two reviews that evaluated interventions that stimulated both activation and collaboration. Of the 4 studies that did not include activation (2 educational, 2 self-directed interventions), 3 achieved positive and 1 achieved mixed results.

Frequency and impact of self-management by condition

Table 3 summarizes the frequency of self-management interventions by domain and component for different types of conditions.

When examined by domain, self-management components that promoted collaboration with health care professionals or others was the least frequently used form of self-management across all studies. The most frequently occurring type of self-management components across all included studies was lifestyle advice (54, 72.0 %), followed by psychological strategies (52, 69.3 %) and information about the condition (37, 49.3 %). The least frequent types of self-management components were links to supportive care resources (2, 2.7 %), information about accomplishing the activities of daily living (9, 12.0 %), and guidance or prompts to facilitate communication with health care professionals (9, 12.0 %). When examined by condition, the frequency of the types of self-management components differed. For example, among the reviews of mental illness, psychological strategies were the most common. Among the reviews of pulmonary conditions, action plans were the most frequently used form of self-management component, followed closely by psychological strategies and lifestyle advice.

Most conditions featured multiple types of self-management components. There did not appear to be trends in the characteristics or impact of self-management by condition. For example, metabolic disease (all diabetes) was the focus of the greatest proportion of reviews (23, 29.9 %). Among these, 13, 3, and 6 were based on educational, self-directed, and multifaceted interventions, respectively (Additional file 2). In 13 reviews that focused on educational interventions by activation alone (1), information and activation (8) or information, activation and collaboration (3), 83.3 % achieved positive or mixed results. In 3 reviews that focused on self-directed interventions by activation alone (1), information and activation (1), or information, activation, and collaboration (1), all achieved positive or mixed results. In 6 reviews that focused on multifaceted interventions by activation alone (1), information and activation (3) or information, activation and collaboration (2), all achieved positive or mixed results.

Discussion

This review was conducted to identify and describe the characteristics of effective self-management interventions that could be packaged in or with guidelines as a means of delivering them directly to patients or indirectly through their providers. Educational sessions were the most frequently used format for delivering self-management, followed by self-directed guides which were largely electronically available. Interventions were based on multiple self-management domains and components, most often by offering information about recommended lifestyle choices and by activating patients to adopt and maintain those lifestyle choices through psychological strategies. It appeared that single or multifaceted interventions were associated with positive outcomes. This included informational-only self-management components and self-management components that included activation alone or in combination with other types of support. Activation was most frequently impactful when combined with informational support.

Several implications can be drawn from these findings. The modified taxonomy of self-management used in this study was easy to apply and able to characterize all of the intervention components described in the included systematic reviews [31]. Therefore, it was further validated and can be used by guideline developers and others as the basis for planning and developing patient-oriented guideline implementation tools that support self-management. Most conditions employed multiple types of self-management components; however, it appeared that even single self-management interventions (based on delivery format) can result in beneficial outcomes. The majority of included studies offered evidence that resources which inform or activate patients can achieve beneficial outcomes. This is relevant to guideline developers who often possess few resources with which to develop and implement guidelines and must therefore decide how to allocate scarce resources by prioritizing the strategies they will use for guideline implementation [12]. This finding is similar to that of a recent meta-review of 25 systematic reviews that compared direct and indirect effect size and dose-response of single and multifaceted strategies which showed no benefit of multifaceted over single strategies [112].

Although studies were few, and the association between self-management characteristics and various outcomes remains to be established, there appears to be multiple types of self-management components that may be effective and could be packaged in or with guidelines. This includes information about the condition and its management, how to accomplish activities of daily living, and lifestyle behaviors that support disease management (inform); tools that enable disease and lifestyle management such as diaries, action plans, monitoring measures and logging templates, and tips for problem-solving, goal-setting, or relaxation (activate); and prompts for when and how to communicate with health care providers or other supportive care agencies (collaborate). Given that, in other research, patients favorably viewed guidelines as a useful source of self-management support [27], and our research showed that few guidelines offered such resources [11], this study reveals numerous opportunities to enhance guidelines as a means of promoting the adoption of guidelines and self-management. Ultimately, the optimal use of guidelines and enhanced integration of self-management into care delivery and self-care may improve the health status of patients with chronic conditions.

Other researchers have also highlighted the need to better implement tools that support patient engagement in their own health care [25] and that guidelines offer a potential vehicle for doing so [26]. Although, in previous research, we produced a framework and considerations with which to assess and adapt existing, or develop new guideline implementation tools [15, 16], further research is needed to apply this guidance to the development of informational or activating tools that specifically support self-management. A variety of theories offer insight on how patient perspectives influence their health-related views and behavior, and can be used to design and then evaluate self-management guideline tools. These include the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior [113, 114]. Normalization Process Theory provides insight on how sociological processes influence the implementation of innovations and could be used to examine how patients and providers adopt and integrate self-management [115]. The PRECEDE-PROCEED model is another useful framework by which to plan or evaluate self-management tools based on patient-specific and external factors that may influence their impact [116].

While patients may see the benefit of accessing self-management support through guidelines, research shows that many patients are not aware of guidelines or where to find them [11]. The Taylor et al. meta-review included a complementary analysis of 30 qualitative systematic reviews and 61 studies on the implementation of self-management programs which revealed that interventions such as education and training, feedback, prompts or reminders, equipment, and financial incentives were needed so that providers offered self-management support to their patients [31]. Other systematic reviews similarly found that educational strategies were needed to prompt health care professionals to adopt patient-centered approaches in clinical consultations such as shared decision-making [117, 118]. The qualitative review included in the Taylor et al. meta-review also emphasized that the effectiveness of self-management was enhanced through good collaboration with providers at the point of care. This review revealed that self-management support to promote collaboration with health care professionals or others was the least frequently used form of self-management across all studies. Thus further research is needed to develop and evaluate resources such as question prompt lists for patients about when and how to communicate with health care providers [119]. Further research is also needed to investigate whether and how guidelines prompt health care professionals to engage in conversations with patients.

A variety of factors limit the interpretation and application of these findings. The literature search, which was not peer-reviewed by another librarian, and screening process may not have identified all relevant studies although we employed a comprehensive search strategy and multiple independent screeners selected eligible articles. The characteristics of self-management interventions in eligible studies may not have been accurately categorized even though data were independently extracted by multiple authors and a research assistant. In part, this is due to the fact that self-management interventions were not well-described in all eligible reviews and, even if the intervention was stated, the type of self-management domain and component was not always explicit and had to be inferred. This may also be due to a general lack of consensus on the definition of self-management and a corresponding confusing array of interventions labelled as self-management in the literature, as was observed here and by Taylor et al. [31]. Others have distinguished self-management education (informs decision-making, self-care, problem-solving) from self-management support (enables adoption and maintenance of self-management behaviors that influence functional outcomes), yet this was not clear in many of the included studies [120, 121]. Moreover, of the 77 studies included, 44 and 18 were found to have a moderate and high risk of bias, respectively. Thus the results reported by 80.5 % of the included reviews should be interpreted with caution and influence the overall findings reported here. That being said, the modified Taylor et al. taxonomy proved to be a useful means of distinguishing between the components of self-management interventions [31]. This systematic review was exploratory in nature and revealed a potential association between the type of self-management support that could be included in or with guidelines and positive impact. However, given the diversity of conditions, interventions employed, and outcomes reported, we were not able to generate a statistical measure of association. Future research could repeat this work but focus on RCTs evaluating single diseases in an effort to examine effect size and confidence intervals, and pool that data. The underlying mechanism of self-management interventions associated with impact could be examined if such a review used realist approach [122]. In that work, self-management interventions could be categorized based on outcome quadrants suggested by De Silva et al. knowledge, technical skill, self-efficacy, and behavior change [123]. Future research could also examine the content of guidelines to characterize the self-management support they offer, thereby identifying exemplars that others could emulate, and gaps where self-management support may be needed.

Conclusions

In this meta-review, single or multifaceted educational or self-directed self-management interventions that included activation support (i.e., reminders, diaries, action plans, tools to monitor health status, psychological strategies for problem-solving) may have reinforced general information about the condition and lifestyle advice, and contributed to the positive impact of self-management interventions as reported in included studies. Given that, in previous research, patients desired self-management support and few guidelines offered such tools, this study revealed numerous opportunities by which to enhance guidelines in a way that supports self-management to contribute to the improved health of patients with a variety of chronic conditions. Further research is needed to establish the statistical association between the characteristics of self-management support and outcomes and to optimize the design of self-management tools for both health care providers and patients that are included in or with guidelines.

References

Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington: National Academies Press; 2013.

Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, Schunemann H, Eccles MP. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci. 2012;7:62.

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N, for the Evidence Based Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348:g37225.

Pronovost PJ. Enhancing physicians’ use of clinical guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310:2501–2.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L, Wensing M, Dijkstra R, Donaldson C. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–72.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N, Wensing M, Fiander M, Eccles MP, Godycki-Cwirko M, van Lieshout J, Jager C. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD005470.

McKillop A, Crisp J, Walsh K. Practice guidelines need to address the “how” and the “what” of implementation. Primary Health Care Res Develop. 2012;13:48–59.

Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R, et al. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132:517–34.

Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke MJ, et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD009401.

Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2005;293:1223–38.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Do guidelines offer implementation advice to target users? A systematic review of guideline applicability. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007047.

Gagliardi AR. “More bang for the buck”: exploring optimal approaches for guideline implementation through interviews with international developers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:404.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Integrating guideline development and implementation: analysis of guideline development manual instructions for generating implementation advice. Implement Sci. 2012;7:67.

Gagliardi AR, Marshall C, Huckson S, James R, Moore V. Developing a checklist for guideline implementation planning: review and synthesis of guideline development and implementation advice. Implement Sci. 2015;10:19.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Bhattacharyya O. A framework of the desirable features of guideline implementation tools (GItools): Delphi survey and assessment of GItools. Implement Sci. 2014;9:98.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Bhattacharyya OK. The development of guideline implementation tools: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:e127–33.

G-I-N PUBLIC. Patient and public involvement in guidelines. Guidelines International Network Public and Patient Involvement Working Group. http://www.g-i-n.net/working-groups/gin-public.

Légaré F, Boivin A, van der Weijden T, Pakenham C, Burgers J, Légaré J, St-Jacques S, Gagnon S. Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31:e45–74.

Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19:CD004563.

Grande SW, Faber MJ, Durand MA, Thompson R, Elwyn G. A classification model of patient engagement methods and assessment of their feasibility in real-world settings. Pat Educ Counsel. 2014;95:281–7.

Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013;32:223–31.

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351–79.

Santesso N, Rader T, Nilsen ES, Glenton C, Rosenbaum S, Ciapponi A, Moja L, Pardo JP, Zhou Q, Schünemann HJ. A summary to communicate evidence from systematic reviews to the public improved understanding and accessibility of information: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:182–90.

Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Manna M, Edward AGK, Clay C, Legare F, van der Weijden T, Lewis CL, Wexler RM, Frosch DL. Many miles to go: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Dec Mak. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S14.

Van der Weijden T, Pieterse AH, Koelewijn-van Loon M, Knaapen L, Legare F, Boivin A, Burgers JS, Stiggelbout AM, Faber M, Elwyn G. How can clinical practice guidelines be adapted to facilitate shared decision making? A qualitative key-informant study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:855–63.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Palda VA, Lemieux-Charles L, Grimshaw JM. How can we improve guideline use? A conceptual framework of implementability. Implement Sci. 2011;6:26.

Loudon K, Santesso N, Callaghan M, Thornton J, Harbour J, Graham K, Harbour R, Kunnamo I, Liira H, McFarlane E, Ritchie K, Treweek S. Patient and public attitudes to and awareness of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review with thematic and narrative syntheses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:321.

Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Rosella H, Hulscher M, Grol R. Integrated care programs for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:4–46.

Adams K, Greiner AC, Corrigan JM, editors. The 1st annual crossing the quality chasm summit—a focus on communities. Washington: The National Academic Press; 2004.

Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7.

Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, Parke HL, Schwappach A, Purushotham N, Jacob S, Griffiths CJ, Greenhalgh T, Sheikh A. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS—practical systematic review of self-management support for long-term conditions. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2014.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org/.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, and The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Siantz E, Aranda MP. Chronic disease self-management interventions for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:233–44.

Bossen D, Veenhof C, Dekker J, De Bakker D. The effectiveness of self-guided web-based physical activity interventions among patients with a chronic disease: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11:665–77.

Kivela K, Elo S, Kaariainen M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97:147–57.

Zhai Y, Zhu W, Cai Y, Sun D, Zhao J. Clinical- and cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2014;93:e312.

Bolen SD, Chandar A, Falck-Ytter C, Tyler C, Perzynski AT, Gertz AM, Sage P, Lewis S, Cobabe M, Ye Y, Menegay M, Windish DM. Effectiveness and safety of patient activation interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1166–76.

Attridge M, Creamer J, Ramsden M, Cannings-John R, Hawthorne K. Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD006424.

McGillion M, O’Keefe-McCarthy S, Carroll SL, Victor JC, Cosman T, Cook A, Hanlon JG, Jolicoeur EM, Jamal N, McKelvie R, Arthur HM. Impact of self-management interventions on stable angina symptoms and health-related quality of life: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:14.

Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PDLPM, Zielhuis GA, Monninkhof EM, van der Palen J, Frith PA, Effing T. Self-management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD002990.

Kroon FPB, van der Burg LRA, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Johnston RV, Pitt V. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD008963.

Köpke S, Solari A, Khan F, Heesen C, Giordano A. Information provision for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD008757.

Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P. Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD005330.

Burns P, Jones SC, Iverson D, Caputi P. Internet self-management uniform reporting framework: the need for uniform reporting criteria when reporting internet interventions. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31:554–65.

Beatty L, Lambert S. A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:609–22.

Franek J. Self-management support interventions for persons with chronic disease: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13:1–60.

McDermott MS, While AE. Maximizing the healthcare environment: a systematic review exploring the potential of computer technology to promote self-management of chronic illness in healthcare settings. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:13–22.

Kuijpers W, Groen WG, Aaronson NK, van Harten WH. A systematic review of web-based interventions for patient empowerment and physical activity in chronic diseases: relevance for cancer survivors. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e27.

Stellefson M, Chaney B, Barry AE, Chavarria E, Tennant B, Walsh-Childers K, Sriram PS, Zagora J. Web 2.0 chronic self-management for older adults: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e35.

Pal K, Eastwood SV, Michie S, Farmer AJ, Barnard ML, Peacock R, Wood B, Inniss JD, Murray E. Computer-based diabetes self-management interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD008776.

Torenholt R, Schwennesen N, Willaing I. Lost in translation- the role of family in interventions among adults with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;31:15–23.

El-Gayar O, Timsina P, Nawar N, Eid W. A systematic review of IT for diabetes self-management: are we there yet? Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:637–52.

Carter BM, Barba B, Kautz DD. Culturally tailored education for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Medsurg Nurs. 2013;22:105–9.

Clarkesmith DE, Pattison HM, Lane DA. Educational and behavioural interventions for anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD008600.

Cumberworth A, Mabvuure NT, Hallam MJ, Hindocha S. Is home monitoring of international normalized ratio safer than clinic-based monitoring? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16:198–201.

De Freitas RFCP, Ferreira MAF, Barbosa GAS, Calderon PS. Counselling and self-management therapies for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:864–74.

Malanda UL, Welschen LMC, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Bot SDM. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD005060.

Nam S, Janson SL, Stotts NA, Chesla C, Kroon L. Effect of culturally tailored diabetes education in ethnic minorities with type 2 diabetes. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27:505–18.

Newlin K, Dyess SM, Allard E, Chase S, Melkus GD. A methodological review of faith-based health promotion literature: advancing the science to expand delivery of diabetes education to Black Americans. J Relig Health. 2012;51:1075–97.

Steinsbekk A, O Rygg L, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim F. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:213.

Tshiananga JK, Kocher S, Weber C, Emy-Albrecht K, Berndt K, Neeser K. The effect of nurse-led diabetes self-management education on glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:108–23.

Forster A, Brown L, Smith J, House A, Knapp P, Wright JJ, Young J. Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD001919.

Ciere Y, Cartwright M, Newman SP. A systematic review of the mediating role of knowledge, self-efficacy and self-care behaviour in telehealth patients with heart failure. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:384–91.

Bentsen SB, Langeland E, Holm AL. Evaluation of self-management interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:802–13.

Tan JY, Chen JX, Liu XL, Zhang Q, Zhang M, Mei LJ, Lin R. A meta-analysis on the impact of disease-specific education programs on health outcomes for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Geriatr Nurs. 2012;33:280–96.

Wong CX, Carson KV, Smith BJ. Home care by outreach nursing for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD000994.

Moullec G, Gour-Provencal G, Bacon SL, Campbell TS, Lavoie KL. Efficacy of interventions to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in adult asthmatics: impact of using components of the chronic care model. Respir Med. 2012;106:1211–25.

Gross A, Forget M, St George K, Fraser MMH, Graham N, Perry L, Burnie SJ, Goldsmith CH, Haines T, Brunarski D. Patient education for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD005106.

Oliveira VC, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Refshauge KM, Ferreira ML. Effectiveness of self-management of low back pain: systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1739–48.

Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. A systematic evaluation of content, structure and efficacy of interventions to improve patients’ self-management of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:264–84.

Coull G, Morris PG. The clinical effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help interventions for anxiety and depressive disorders: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2239–52.

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R, Mohr DC, van Straten A, Andersson G. Self-guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21274.

Inouye J, Braginsky N, Kataoka-Yahiro M. Randomized clinical trials of self-management with Asian/Pacific islanders. Clin Nurs Res. 2011;20:366–403.

Li T, Wu HM, Wang F, Huang CQ, Yang M, Dong BR, Liu GJ. Education programmes for people with diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6:CD007374.

Lennon S, McKenna S, Jones F. Self-management programmes for people post stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:867–78.

Bloomfield HE, Krause A, Greer N, Taylor BC, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Reddy P, Wilt TJ. Meta-analysis: effect of patient self-testing and self-management of long term anticoagulation on major clinical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:472–82.

Du S, Yuan C, Xiao X, Chu J, Qiu Y, Qian H. Self-management programs for chronic musculosckeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e299–310.

Rae-Grant AD, Turner AP, Sloan A, Miller D, Hunziker J, Haselkorn JK. Self-management in neurological disorders: systematic review of the literature and potential interventions in multiple sclerosis care. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48:1087–100.

Minet L, Moller S, Vach W, Wagner L, Henriksen JE. Mediating the effect of self-care management interventions in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of 47 randomised controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:29–41.

Heinrich E, Schaper NC, de Vries NK. Self-management interventions for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Eur Diabetes Nurs. 2010;7:71–6.

Matteson ML, Russell C. Interventions to improve hemodialysis adherence: a systematic review of randomized-controlled trials. Hemodialysis Int. 2010;14:370–82.

Dorn SD. Systematic review: self-management support interventions for irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:513–21.

Bray EP, Holder R, Mant J, McManus RJ. Does self-monitoring reduce blood pressure? Meta-analysis with meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2010;42:371–86.

Saksena A. Computer-based education for patients with hypertension: a systematic review. J Health Educ. 2010;69:236–45.

Albano MG, Giraudet-Le Quintrec JS, Crozet C, d’Ivernois JF. Characteristics and development of therapeutic patient education in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of the 2003-2008 literature. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:405–10.

Iversen MD, Hammond A, Betteridge N. Self-management of rheumatic diseases: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:955–63.

Graziano JA, Gross CR. The effects of isolated telephone interventions on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;32:E28–41.

Duke SAS, Colagiuri S, Colagiuri R. Individual patient education for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD005268.

Hwang R, Marwick T. Efficacy of home-based exercise programmes for people with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2009;16:527–35.

Williams A, Manias E, Walker R. Interventions to improve medication adherence in people with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63:132–43.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Brown SA, Brown LM. Meta-analysis of patient education interventions to increase physical activity among chronically ill adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:157–72.

Khunti K, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Carey M, Davies MJ, Stone MA. Educational interventions for migrant South Asians with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:985–92.

Mason J, Khunti K, Stone M, Farooqi A, Carr S. Educational Interventions in kidney disease care: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:933–51.

Brox JI, Storheim K, Grotle M, Tveito TH, Indahl A, Eriksen HR. Systematic review of back schools, brief education and fear-avoidance training for chronic low back pain. J Spine. 2008;8:948–58.

Bradley PM, Lindsay B. Care delivery and self-management strategies for adults with epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD006244.

Foster G, Taylor SJC, Eldridge S, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005108.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR, LeMaster JW, Brown SA, Nielsen PJ. Metabolic effects of interventions to increase exercise in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:913–21.

Sigurdardottir AK, Jonsdottir H, Benediktsson R. Outcomes of educational interventions in type 2 diabetes: WEKA data-mining analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:21–31.

Blackstock F, Webster KE. Disease-specific health education for COPD: a systematic review of changes in health outcomes. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:703–17.

Tapp S, Lasserson TJ, Rowe BH. Education interventions for adults who attend the emergency room for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD003000.

Liddle SD, Gracey JH, Baxter GD. Advice for the management of low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Man Ther. 2007;12:310–27.

Renz A, Ide M, Newton T, Robinson P, Smith D. Psychological interventions to improve adherence to oral hygiene instructions in adults with periodontal diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005097.

Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner ML, Gary TL. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:105–10.

Heneghan C, Alonso-Coello, Gracia-Alamino JM, Perera R, Meats E, Glasziou P. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation. Lancet. 2006;367:404–11.

Anderson L, Lewis G, Araya R, Elgie R, Harrison G, Proudfoot J, Schmidt U, Sharp D, Weightman A, Williams C. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice? Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:384–6.

Deakin TA, McShane CE, Cade JE, Williams R. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD003417.

Van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HFMJ, van der Borne BHW. Social support in diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:1–12.

Welch JL, Thomas-Hawkins C. Psycho-educational strategies to promote fluid adherence in adult hemodialysis patients: a review of intervention studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:597–608.

Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes BW. Back schools for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration back review group. J Spine. 2005;30:2153–63.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single component interventions in changing healthcare professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9:152.

Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 45–66.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behavr Human Dec Proc. 1991;50:179–211.

McEvoy R, Ballini L, Maltoni S, O’Donnell CA, Mair FS, Macfarlane A. A qualitative systematic review of studies using the normalization process theory to research implementation processes. Implement Sci. 2014;9:2.

Carsen-Gielen A, McDonald EM, Gary TL, Bone LR. Chapter 18. Using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model to apply health behavior theories. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Behavior and health education. Theory, research and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

Dwamena F, Homes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, Lewin S, Smith RC, Coffey J, Olomu A, Beasley M. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, Turcotte S. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD006732.

Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Ryan R, Prout H, Cadbury N, MacBeth F, Butow P, Butler C. Interventions before consultations to help patients address their information needs by encouraging question asking: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a485.

Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159–71.

Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, Cox CE, Duker P, Edwards L, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 Suppl 1:S144–53.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2005;10:21–34.

De Silva D. Helping people help themselves. London: The Health Foundation; 2011 [http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/HelpingPeopleHelpThemselves.pdf, accessed February 2016].

Acknowledgements

Members of the Guidelines International Network Guideline Implementation Working Group reviewed this manuscript to further refine the interpretation of findings and enhance communication of the findings. They included:

• Melissa Armstrong, University of Florida, USA

• Melissa Brouwers, McMaster University, Canada

• André Bussières, McGill University, Canada

• Margot Fleuren, Organisation for Applied Scientific Research TNO, Netherlands

• Kari Gali, Case Western Reserve University, USA

• Sue Huckson, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, Australia

• Stephanie Jones, American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, USA

• Sandra Zelman Lewis, EBQ Consulting, USA

• Roberta James, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, UK

• Catherine Marshall, Guideline and Health Sector Consultant, New Zealand

• Danielle Mazza, Monash University, Australia

The Guidelines International Network (G-I-N; www.g-i-n.net) is a Scottish Charity (SC034047). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and G-I-N is not liable for any use that may be made of the information presented.

Funding

This study was undertaken with no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ARG envisioned and planned the study and provided funding for research assistant support; all authors established study objectives, collected and analyzed data, drafted the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

MEDLINE search strategy. Search strategy as applied in MEDLINE. (DOCX 13.2 kb)

Additional file 2:

Data extracted from eligible studies. Data extracted from eligible studies. (DOCX 25.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Vernooij, R.W.M., Willson, M., Gagliardi, A.R. et al. Characterizing patient-oriented tools that could be packaged with guidelines to promote self-management and guideline adoption: a meta-review. Implementation Sci 11, 52 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0419-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0419-1