Abstract

Background

An ethnobotanical field study on the traditional uses of wild plants for food as well as medicinal and veterinary plants was conducted in four Waldensian valleys (Chisone, Germanasca, Angrogna, and Pellice) in the Western Alps, Piedmont, NW Italy. Waldensians represent a religious Protestant Christian minority that originated in France and spread around 1,170 AD to the Italian side of Western Alps, where, although persecuted for centuries, approximately 20,000 believers still survive today, increasingly mixing with their Catholic neighbours.

Methods

Interviews with a total of 47 elderly informants, belonging to both Waldensian and Catholic religious groups, were undertaken in ten Western Alpine villages, using standard ethnobotanical methods.

Results

The uses of 85 wild and semi-domesticated food folk taxa, 96 medicinal folk taxa, and 45 veterinary folk taxa were recorded. Comparison of the collected data within the two religious communities shows that Waldensians had, or have retained, a more extensive ethnobotanical knowledge, and that approximately only half of the wild food and medicinal plants are known and used by both communities. Moreover, this convergence is greater for the wild food plant domain. Comparison of the collected data with ethnobotanical surveys conducted at the end of the 19th Century and the 1980s in one of studied valleys (Germanasca) shows that the majority of the plants recorded in the present study are used in the same or similar ways as they were decades ago. Idiosyncratic plant uses among Waldensians included both archaic uses, such as the fern Botrychium lunaria for skin problems, as well as uses that may be the result of local adaptions of Central and Northern European customs, including Veronica allionii and V. officinalis as recreational teas and Cetraria islandica in infusions to treat coughs.

Conclusions

The great resilience of plant knowledge among Waldensians may be the result of the long isolation and history of marginalisation that this group has faced during the last few centuries, although their ethnobotany present trans-national elements.

Cross-cultural and ethno-historical approaches in ethnobotany may offer crucial data for understanding the trajectory of change of plant knowledge across time and space.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethnobotanical studies of minority and diasporic groups are of crucial interest in contemporary ethnobiology to help identify those cultural and/or social factors which affect the perceptions and uses of plants and to understand how traditional plant knowledge evolves [1-8].

Moreover, diverse analyses conducted in Europe during the last decade have pointed out that a broad range of factors influence the resilience of ethnobotanical knowledge and are able to slow or accelerate its erosion, including environmental changes, internal (urbanisation) and external migrations, self-perception and that of others’ identities, language, religion, as well as economic or political externalities [9-16].

On the other hand, the Alps have been shown to still represent an important reservoir of local, folk plant knowledge, both in touristic [17,18] and especially in “peripheral” valleys [19-22], which have been less affected by the mass tourism industry.

Along these theoretical trajectories, our ethnobotanical research in recent years has focused on a number of linguistic “isles” and cultural boundaries in mountainous areas of Italy and the Balkans; especially in the latter cultural region, we have also observed the effect that religious affiliation has on the vertical transmission of folk plant knowledge, as it remarkably shapes kinship relations within multi-lingual and multi-religion communities [23].

In order to further assess the role that religion plays in shaping folk plant knowledge, we decided to investigate the local ethnobotany of the Waldensian community and that of their Catholic neighbours in the Western Alps, NW Italy. Waldensians represent a religious Christian (and later Protestant Christian) minority that originated in France during the 12th Century which spread around 1,170 AD to the Italian side of the Cottian (Western) Alps. Harassed for centuries, Waldensians went through a long and dramatic history of persecutions, migrations and relocations, and, despite the isolation and marginalisation of their valleys, they built important ties to Protestant countries, notably England, the Netherlands, and Switzerland [24].

Nowadays, approximately 20,000 believers (Provençal/Occitan, Piedmontese and standard Italian speaking) still survive in these valleys, increasingly mixing with their Catholic neighbours.

The specific aims of this study were:

-

1.

to record the local names and specific uses of wild food plants, as well as wild and non-wild plants for medicinal and veterinary practices in four Waldensians valleys;

-

2.

to compare the ethnobotany of members belonging to the two faiths (Waldensians and Catholics); and

-

3.

to diachronically compare the current data with those from the historical North Italian ethnobotanical data.

Methods

Selected sites

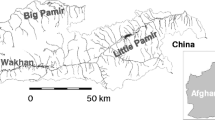

Figure 1 shows the location of the study sites, which were represented by four Waldensian valleys (Chisone, Germanasca, Angrogna, and Pellice) located in the Western Alps, Piedmont, NW Italy.

The valleys are characterized by chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.), beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), and larch (Larix decidua Mill.) forests, with some Scots pine (Pinus sylvatica L.); the climate is alpine, with relevant annual precipitations (1000–2000 mm/year).

In particular, the following villages were visited: Fenestrelle (1,138 m.a.s.l.), Mentoulles (1,046 m.a.s.l.), Villaretto (986 m.a.s.l.), Pomaretto (619 m.a.s.l.), Campo La Salza (1,140 m.a.s.l.), Massello (1,187 m.a.s.l.), San Martino (1,063 m.a.s.l.), Villasecca (832 m.a.s.l.), Angrogna (582 m.a.s.l.), and Bobbio Pelice (762 m.a.s.l.).

All villages officially report a few hundred inhabitants (normally 300–500), but the actual figures are largely overestimated, as a significant portion of the current resident populations lives in the lowland Piedmontese centres and Turin and comes back to the villages only during the summer or on the weekends.

The local economy, since a few decades, is no longer based on agro-pastoral activities, and the elderly inhabitants live off of their pensions and in their free time manage some home-gardens and/or small-scale agricultural activities. Young and mid generations work instead in the main lowlands centres and in Turin.

Mass tourism is absent, although some eco-touristic initiatives have been growing in recent years.

The original Waldensian inhabitants have increasingly mixed with their Catholic neighbours in the last few decades, and in most cases intermarriage leads to a family’s change of faith (from Waldensian to Catholic).

Nowadays the language spoken within the domestic arena is increasingly a mixture of the original Provençal/Occitan language with the Piedmontese variety of Italian. All inhabitants also speak standard Italian.

Field study

In the years 2010–2014, forty-seven elderly informants (nineteen Catholics and twenty-eight Waldensians, aged between 58 and 78 years) were selected, among those locals who could be identified as Traditional Knowledge holders (normally elderly small-scale farmers and shepherds), employing snowball sampling techniques. These individuals then were interviewed after Prior Informed Consent was verbally obtained.

The focus of the interviews, which were conducted in standard Italian, was the folk knowledge (name and use) of wild food plants and wild and non-wild medicinal and veterinary plants.

The Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology [25] was strictly followed.

The wild plant species mentioned by the informants were collected, when available, identified according to Flora d’Italia [26], and finally stored at the Herbarium of the University of Gastronomic Sciences.

Plant family assignments follow the current Angiosperm Phylogeny Group designations [27].

The reported folk plant names were transcribed using the rules of the Provençal/Occitan and standard Italian languages.

Data analysis

We compared the data gathered among local Waldensians with those collected among Catholics in the same study sites.

Moreover, we compared our findings with those observed in two ethnobotanical field studies conducted in the same areas (Val Germanasca) at the end of the 19th Century and in the 1980s [28-30]. In particular, the first work represents one of the very first ethnobotanical studies in Italy as well as the whole of Europe, which was conducted by a Waldensian botanist working as a secondary school teacher, who died from an infectious disease in Uruguay, where he immigrated one year after the publication of his investigation [31].

Results and discussion

Wild food plants

Table 1 shows the recorded uses of the wild food and semi-domesticated plant taxa.

The collection of the young aerial parts of the following wild vegetables is still common in the study area: Borago officinalis, Primula spp., Nasturtium officinale, Lapsana communis, Chenopodium bonus-henricus, Rumex acetosa, Tragopogon pratensis, Urtica dioica, Silene vulgaris, Humulus lupulus, and Taraxacum officinale.

The above confirms what we already know about wild food plant consumption in Italy and in particular NW Italy, where the very common consumption of the young shoots of Humulus lupulus and Tragopogon pratensis can be considered a cultural marker of Piedmontese cuisine. While all these data confirm the observations reported nearly one century ago by Giovanni Mattirolo in his review of the wild plants of Piedmont [32], it appears that the practice of gathering and consuming the leaves/young shoots of Valerianella locusta, Phyteuma spp., Persicaria bistorta, and Aruncus dioicus continued only until the recent past and/or is less common today. The latter three species (in soups or boiled) in particular represent an important part of the slowly disappearing North Italian Alpine culinary “traditions” [17,33].

Among the wild plants exploited for seasoning, the use of Carum carvi, Thymus serpyllum, Juniperus communis, and Tanacetum vulgare is predominant. In particular, the common use of the leaves of the last species (Figure 2) – which has been widely reported not only in the Piedmont region but also recently in Occitan/Provençal and Alpine Ligurian areas [17,22,34,35] – as a crucial seasoning ingredient in omelettes, soups, and a home-made liqueur called arquebuse may be better investigated from a historical perspective. In fact, this species has a long history of folk use in Britain, especially in omelettes consumed during the fish-based diet of Lent [36], and Waldensians, even in the poorest villages, have maintained for many centuries intense cultural ties to Britain, due to the historical and theological proximity between the Protestant/Anglican and Waldensian faiths [23].

As in other areas of NW Italy ([17], and references therein), wild Artemisia genipi, A. glacialis, and A. umbelliformis flowering tops (genepì), Gentiana acaulis flowers (Figure 3) and roots, and G. lutea roots are commonly gathered and used for making home-made hydro-alcoholic macerates/digestive liqueurs.

Among wild fruits, the gathering of the fruits/pseudo-fruits of Rosa canina, Sambucus nigra (and rarely S. racemosa), and Vaccinium myrtillus is still commonly practiced.

Finally, the frequent use of the aerial parts of Veronica species (esp. the local Veronica allionii) as recreational teas in the study area, which has also been recorded in adjacent valleys [17], could be the result of cultural “contamination” from British and Northern/Central European customs. Waldensians, for example, have introduced in their valleys, and continue to practice today, the English custom of taking afternoon tea, which is extremely uncommon among the autochthonous Catholics in the study area as well as other areas of Italy.

In place of exotic and expensive colonial teas, the poor villagers may have opted for a “cheap”, local substitute, which may explain the use of the aerial parts of Veronica spp. even today. This tea – sometimes locally and more recently called “Occitan tea” - became in the last decade in the study area and also among the entire Occitan/Provençal community living in the Western Italian Alps an important cultural marker and seems to represent there one of the distinctive signs of the local identity.

On the other hand, the use of Veronica officinalis tea was very spread in France, Switzerland, and Northern Europe in the 19th Century [37].

Medicinal plants

Table 2 reports the locally recorded medicinal plant uses.

The most common wild medicinal plant-based remedies, which are used externally, comprise the flowers of Arnica montana, the aerial parts of Artemisia absinthium, the resin of Abies alba, and the fresh latex of Chelidonium majus. Apart from the last species, this finding confirms the recent ethnobotanical data gathered from other Italian Alpine areas [17-22].

Among the less commonly reported species, the use of the fern Botrychium lunaria for skin problems should be further investigated, as the use of this plant was not recorded in the Italian ethnobotanical database compiled in 2004 [38], and the phytochemistry and pharmacology of the genus Botrychium is largely unknown, if we exclude the recent work on its flavonoids [39].

The most frequently mentioned local herbal infusions are instead prepared with plants that are commonly used throughout Italy and Europe: Equisetum arvense, Hypericum perforatum, Parietaria officinalis, Malva sylvestris, Matriciaria chamomilla, Thymus serpyllum, Tilia cordata, Viola tricolor, and Cetraria islandica. The use of the last species is peculiar, however, as it is frequently found, in Italy, in the herbalism-based standardized phytotherapy, but not often in the local folk medical systems.

The remarkable tradition of gathering and using this wild lichen in Waldensian valleys may be, once again, the result of the historical ties that these communities retained with Central and Northern European customs.

The same lichen, gathered from the wild, is also nowadays one of the pillars of the resurgence of the traditional Waldensian cuisine, where it is sometimes used to prepare desserts in a few of the new restaurants in the area [40].

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the unsual herbal folk uses of Cetraria islandica and Botrychium lunaria find parallelisms in the Alpine Catalan ethnobotany [41,42], showing in this way interesting commonalities between the Catalan and Occitan ethnobotanies of the Alpine communities.

Veterinary plants

Nearly all the plants pertaining to the veterinary domain (plants used for both feeding and for curing animals, Table 3) were used primarily in the past, as current uses are sporadic and quotation indexes are very low.

This suggests that the socio-economic shift local communities have faced since the 1960s, in which most inhabitants have abandoned the traditional agro-pastoral activities and animal breeding has decreased, has also produced a dramatic loss of Traditional Knowledge concerning veterinary practices.

Waldensian versus Catholic ethnobotany: the possible role of cultural isolation from neighbours

Figure 4 illustrates the overlap between the ethnobotany of Waldensians and that of their Catholic neighbours in the three analysed domains (folk wild plant foods, medicines, and veterinary food plants and remedies).

The comparison shows that Waldensians had, or have retained, a more extensive ethnobotanical knowledge, and that approximately only half of the recorded wild food and medicinal plants are known and used by both communities. Moreover, this convergence is more marked for the wild food plant domain.

Despite the fact that Waldensians nowadays live together with Catholics, intermarriage between the two religious communities did not exist until a few decades ago. Given the fact that vertical transmission (from grandmother to mothers and from mothers to daughters) of ethnobotanical knowledge is related to kinship networks and these are determined by religious affiliation, this factor may explain the divergence of the two ethnobotanies.

Moreover, the fact that the plant knowledge among Waldensians appears to be more extensive than among the Catholic population may be related to a less marked erosion of the traditional customs and the strong sense of identity Waldensians retain. The historical isolation of the Waldensian community, which survived for many centuries cut off from the rest of their neighbours but at the same time fostered strong ties to Central and Northern Europe, may have facilitated unique patterns of plant perception and use.

However, in the last few decades intermarriage between members of the two communities has become more common (generally bringing the new family into the Catholic faith), and this will probably further hybridize the ethnobotany of the two groups.

On the other hand, a stronger overlap of the ethnobotanies of two culturally distinct groups in the specific wild food domain has also been observed in other mountainous regions of Europe, and may be regarded as a common strategy for coping with the food security-centred struggles that marginalised Alpine populations had to face in the past [1].

The Waldensian ethnobotany during the last century: a historical analysis

Table 4 illustrates the overlap of ethnobotanical data collected at the end of the 19th Century and in the 1980s in one of the study valleys (Germanasca Valley) [28-30] with our current data.

Although few plants were reported in the ethnobotanical study published in 1900 [28,29] and few taxa were reported with their local names in the survey published in 1984 [30] (thus suggesting maybe a sampling based mainly on trained herbalists), more than half of these species recorded in these two studies are used in the same of similar ways today.

However, possible different research methods used in the current and past field studies make a detailed comparison very problematic, as in both of the past considered surveys, which were conducted by botanists, an exact description of the utilized sampling and ethnographic methods and, paradoxically, even an indication of collected plant vouchers are completely missing.

The comparative analysis shows in any case a remarkable degree of resilience of traditional plant uses in the study area, despite the tremendous socio-economic changes that occurred during the last 120 years; other diachronic analyses recently conducted in the Balkans have also confirmed the survival of 19th Century folk plant uses to today [16,43].

Conclusions

Local plants have played, and still partially play, an important role in the context of food security and emic, domestic pathways of the management of human and animal health in the Western Alps.

A marked persistence of local knowledge regarding these plants among Waldensians confirms the importance of studying enclaves as well as cultural and linguistic “isles” in ethnobotany, which may represent both crucial reservoirs of folk knowledge and bio-cultural refugia [44].

On the other hand, the findings of this study indicate that a proper conservation of the bio-cultural heritage, such as the ethnobotanical one, requires strategies, which carefully consider natural landscapes and resources as well as cultural and religious customs, since plant folk knowledge systems are the result of a continuous interplay between these two domains over centuries.

Finally, these neglected local plant resources may represent a key issue for fostering a sustainable development in an area of the Alps, which has been largely untouched by mass tourism and is looking with particular interest at eco-touristic trajectories.

References

Quave CL, Pieroni A. A reservoir of ethnobotanical knowledge informs resilient food security and health strategies in the Balkans. Nat Plants. 2015;1:14021.

Pieroni A, Quave CL. Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: a comparison. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:258–70.

Menendez-Baceta G, Aceituno-Mata L, Molina M, Reyes-García V, Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Medicinal plants traditionally used in the northwest of the Basque Country (Biscay and Alava), Iberian Peninsula. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:113–34.

di Tizio A, Luczaj LJ, Quave CL, Redzic S, Pieroni A. Traditional food and herbal uses of wild plants in the ancient South-Slavic diaspora of Mundimitar/Montemitro (Southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:21.

Pirker H, Haselmair R, Kuhn E, Schunko C, Vogl CR. Transformation of traditional knowledge of medicinal plants: the case of Tyroleans (Austria) who migrated to Australia, Brazil and Peru. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8:44.

Kujawska M, Hilgert NI. Phytotherapy of polish migrants in Misiones, Argentina: Legacy and acquired plant species. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:810–30.

Kujawska M, Pieroni A. Plants used as food and medicine by polish migrants in Misiones, Argentina. Ecol Food Nutr. 2015;54:255–79.

Pieroni A, Cianfaglione K, Nedelcheva A, Hajdari A, Mustafa B, Quave CL. Resilience at the border: traditional botanical knowledge among Macedonians and Albanians living in Gollobordo, Eastern Albania. J Ethnobiolo Ethnomed. 2014;10:31.

Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Pieroni A. Resilience of Andean urban ethnobotanies: a comparison of medicinal plant use among Bolivian and Peruvian migrants in the United Kingdom and in their countries of origin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:27–54.

Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Torry B, Pieroni A. Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: the Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:342–59.

Łuczaj Ł. Changes in the utilization of wild green vegetables in Poland since the 19th century: a comparison of four ethnobotanical surveys. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:395–404.

Sõukand R, Kalle R. The use of teetaimed in Estonia, 1880s-1990s. Appetite. 2012;59:523–30.

Sõukand R, Kalle R. Change in medical plant use in Estonian ethnomedicine: a historical comparison between 1888 and 1994. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:251–60.

Pieroni A, Sheikh QZ, Ali W, Torry B. Traditional medicines used by Pakistani migrants from Mirpur living in Bradford, Northern England. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:81–6.

Pieroni A, Gray C. Herbal and food folk medicines of the Russlanddeutschen living in Künzelsau/Taläcker, South-Western Germany. Phytother Res. 2008;22:889–901.

Pieroni A, Rexhepi B, Nedelcheva A, Mustafa B, Hajdari A, Kolosova V, et al. One century later: the folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:22.

Pieroni A, Giusti ME. Alpine ethnobotany in Italy: traditional knowledge of gastronomic and medicinal plants among the Occitans of the upper Varaita valley, Piedmont. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:32.

Vitalini S, Iriti M, Puricelli C, Ciuchi D, Segale A, Fico G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy) - An alpine ethnobotanical study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:517–29.

Dei Cas L, Pugni F, Fico G. Tradition of use on medicinal species in Valfurva (Sondrio, Italy). J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;163:113–34.

Vitalini S, Tomè F, Fico G. Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Valvestino (Italy). J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:106–16.

Abbet C, Mayor R, Roguet D, Spichiger R, Hamburger M, Potterat O. Ethnobotanical survey on wild alpine food plants in Lower and Central Valais (Switzerland). J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:624–34.

Mattalia G, Quave CL, Pieroni A. Traditional uses of wild food and medicinal plants among Brigasc, Kyé, and Provençal communities on the Western Italian Alps. Genet Res Crop Evol. 2013;60:587–603.

Pieroni A, Giusti ME, Quave CL. Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the western Balkans: medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia. Hum Ecol. 2011;39:333–49.

Tourn G, Valdesi I. La singolare vicenda di un popolo-chiesa (1170–2008). Torino: Claudiana; 2008.

International Society of Ethnobiology. The ISE Code of Ethics. http://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/ (2008). Accessed 25 Jan 2015.

Pignatti S. Flora d’Italia. Bologna: Edagricole, Bologna; 1997.

Stevens PF. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 13. http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/ (2012). Accessed 12 March 2015.

Pons G. Primo contributo alla flora popolare valdese. Boll Soc Ital Bot. 1900;101–09.

Pons G. Flora popolare valdese, secondo contributo. Boll Soc Ital Bot. 1900;216–222.

Lomagno Caramiello R, Piervittori R, Lomagno PA, Rolando C. Fitoterapia popolare nelle valli Chisone e Germanasca. Nota prima: Valle Germanasca e bassa Val Chisone. Ann Fac Sci Agr Univ Torino. 1984;XIII:259–98.

Pieroni A, Quave CL. Pioneering ethnobotanists in Italy. In: Svanberg I, Łuczaj Ł, editors. Pioneers in European ethnobiology. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet; 2014. p. 263–71.

Mattirolo G. “Phytoalimurgia Pedemontana” ossia Censimento delle Specie vegetali alimentari della Flora spontanea del Piemonte. Torino: Bona; 1918.

Ghirardini MP, Carli M, del Vecchio N, Rovati A, Cova O, Valigi F, et al. The importance of a taste. A comparative study on wild food plant consumption in twenty-one local communities in Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:22.

Musset D, Dorothy D. La mauve et l’erba bianca. Salagon: Musée départimental ethnologique de Haute-Provence; 2006.

Cornara L, La Rocca A, Terrizzano L, Dente F, Mariotti MG. Ethnobotanical and phytomedical knowledge in the North-Western Ligurian Alps. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:463–84.

Mabey R. Flora Britannica. The definitive new guide to wild flowers, plants and trees. London: Chattus & Windus; 1997.

Leyel CF. Herbal dilights. London: Faber & Faber; 1937.

Guarrera PM. Usi e tradizioni della flora italiana. Medicina popolare ed etnobotanica. Roma: Aracne; 2006.

Warashina T, Umehara K, Miyase T. Flavonoid glycosides from Botrychium ternatum. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2012;60:1561–73.

Pizzardi G, Eynard W. La Cucina Valdese. Torino: Claudiana; 2006.

Agelet A, Vallès J. Studies on pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the region of Pallars (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). Part III. Medicinal uses of non-vascular plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:229–34.

Rigat M, Bonet MA, Garcia S, Garnatje T, Vallès J. Studies on pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the high river Ter valley (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;13:267–77.

Łuczaj Ł, Dolina K. A hundred years of change in wild vegetable use in southern Herzegovina. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;166:297–304.

Barthel S, Crumley CL, Svedin U. Biocultural refugia: combating the erosion of diversity in landscapes of food production. Ecol Soc. 2013;18:71.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to all the study participants, who graciously agreed to share their folk plant knowledge and to the students of the University of Gastronomic Sciences Giovanni Marabese, Stefano Reverdito, Matteo Belloni, Adriano Piazza, Aurelia Blanc, and Riccardo Mazzoni, who gathered some of the data in the Angrogna Valley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AP conceived the study; GB gathered the data in the field in the Germanasca and Chisone valleys, while AP gathered the data in the Pellice and Angrogna valleys; AP and GB analysed the collected data; AP drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bellia, G., Pieroni, A. Isolated, but transnational: the glocal nature of Waldensian ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 11, 37 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0027-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0027-1