Abstract

Background

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a complex and partially understood disease defined by mucin deposits in the peritoneal cavity, mostly of appendiceal origin caused by the rupture of a mucocele often containing Low or High grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN/HAMN). Other origins include primitive ovarian mucinous cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma almost always with an associated teratoma, but to our knowledge no case of ovarian teratomatous appendiceal-like mucocele with LAMN has been reported as a cause of PMP.

Case presentation

A 25-year old female with infertility was diagnosed with an isolated left ovarian tumor in a context of PMP. Histological examination revealed an ovarian teratoma containing an appendiceal-like structure with mucocele and LAMN, without any associated lesion of the appendix on full histological analysis. Molecular characterization of the ovarian lesion showed co-KRAS and GNAS mutations, as described in PMP of appendiceal origin, while only KRAS mutations are reported in primitive ovarian mucinous tumor.

Conclusions

Detection of co-KRAS and GNAS mutations in our case of ovarian teratomatous appendiceal-like mucocele with LAMN shows that when PMP derives from a mucinous ovarian lesion (with histological proof of none-appendiceal involvement), it is probably of a digestive teratomatous origin, emphasizing the need to actively search for tetatomatous signs in a context of ovarian PMP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei (PMP) is a rare neoplastic disease defined by the presence of mucinous ascites or mucinous deposits in the peritoneal cavity. It is a rare disease whose incidence is approximately 1 to 2 cases per million people per year and which affects more commonly women. Its clinical manifestations are abdominal distention, pain and transit disorder. Its complex physiopathology remains unclear. The majority of PMP are of appendiceal origin due to rupture of a mucocele associated with a low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) or a high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (HAMN). However, in a few cases, tumors of other origins, especially ovarian, may be associated with PMP. Indeed, the description of authentic cases of PMP without appendiceal involvement but with associated ovarian tumor have confirmed its ovarian origin. Primitive ovarian PMP are thought to develop from a broad spectrum of mucinous ovarian entities, from mucinous cystadenoma to borderline cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma, almost always in the context of an associated teratoma. Mucinous proliferation in teratoma is well described but to our knowledge, no teratomatous LAMN has been reported. We describe a case of PMP caused by a ruptured appendiceal-like mucocele associated with LAMN in an ovarian teratoma. Our investigations provide clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and molecular data. We also conducted a literature review about PMP origin, especially ovarian.

Case presentation

Clinical context

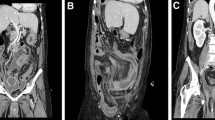

A 25-year-old woman, without previous medical history, presented for infertility lasting for more than one year. Clinical examination was normal but abdominal and pelvic computed tomodensitometry (CT) revealed a cyst of the left ovary associated with abundant peritoneal ascites that could correspond to mucinous material. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed ascites and showed a heterogeneous mass of the left ovary measuring 8.4 × 6.8 cm with adipose, solid and cystic regions that were suggestive of a dermoid cyst. The right ovary and uterus seemed normal. No other lesion was seen in the rest of the body, notably in the digestive system. In this context, surgery by left oophorectomy with appendicectomy and omentectomy was performed 3 months after the first consultation, without resorting to additional hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Intra-operative examination revealed mucinous material inside the peritoneal cavity and a normal digestive tract with a normal appendix. There was no complication of the surgery. The 5-month follow-up based on clinical and imaging surveillance revealed no complaints. Without relapse, the patient was able to pursue her plan to have a child.

Histopathological findings

Macroscopically, the left ovary was cystic measuring 9.5 × 7 × 7 cm and weighing 305 g. It was ruptured on 4 cm. Its cut section revealed a heterogeneous and viscous mass with hair. The appendix, measuring 6 cm in length, and the omentum were macroscopically normal. Histologically, the ovarian cyst corresponded to a mature pluritissular teratoma with intermingled skin and pilosebaceous annexes, serous and mucinous glands, respiratory epithelium, adipose tissue and smooth muscle (Fig. 1). The organoid areas with the aspect of a colon, representing about 20% of the ovarian cyst, were composed of colonic mucosa, muscularis mucosae, and submucosa from the surface to the depth. A thick muscularis propria was also observed. In the colonic mucosa, some glands were elongated and layered with moderate proliferating epithelial cells with minimal atypia, near to mucin pools stained with Alcian blue. The colonic epithelial cells were immunohistochemistry stained with CK20 and CDX2, and showed heterogeneous staining for CK7. These cells were negative for estrogen and progesterone receptors (Fig. 2). The ovarian surface was covered with hyperplastic mesothelial cells and presented acellular mucinous pools, also found in the omentum. The left fallopian tube was normal. The appendix examined in totality was histologically normal besides mucin deposits on the surface of the serosa. It did not present any mucocele or LAMN/HAMN. All together, these data suggested a diagnosis of acellular PMP (according to Carr classification [1]) caused by a ruptured appendiceal-like mucocele associated with LAMN, in a left ovarian teratoma.

Histological aspects of the ovarian teratoma (a-f) and the normal appendix (g). Views of the organoid colonic/appendiceal wall inside the ovarian teratoma at the top, composed of mucosa, muscularis mucosae, submucosa and muscularis propria, with dissociated mucus at left, close to some squamous teratomatous element at the bottom, without any magnification (a) and with low-power magnification Gx25 (b). Focus on colonic/appendiceal LAMN comprising elongated glands layered by mild atypical proliferating cells producing mucin at magnification Gx50 (c), Gx100 (d) and Gx200 (e). View of other teratomatous elements, mostly of cutaneous epithelium and glands at magnification Gx50 (f), and of the histologically normal appendix without magnification (g)

Molecular features

Next generation sequencing of the LAMN of the teratomatous mucocele revealed an activating mutation of KRAS gene c.35G > A corresponding to the p.(Gly12Asp) substitution (Fig. 3). Complementary molecular analysis by SNaPshot showed an associated mutation of GNAS c.602G > A resulting in p.(Arg201His). No mutation was found by these two techniques on the other tissues of the ovarian teratoma (squamous, respiratory, adipose or smooth muscle elements) or in the normal appendix and ovarian parenchyma (Fig. 4).

Mutational status of GNAS gene in teratomatous LAMN, ovarian teratoma and appendix by SNaPshot analysis. In the teratomatous LAMN there was a c.602C > T (reverse) corresponding to a c.602G > A (forward) mutation in GNAS (a) while in the other tissues of the teratoma (b) and in the normal appendix (c) there was no mutation detected in GNAS

Discussion

PMP is caused by the peritoneal localization of mucin, almost exclusively in the context of a tumor, by two possible mechanisms: tumor rupture in the peritoneal cavity causing the spread of mucinous material containing a variable amount of tumor cells, or peritoneal metastasis of a mucinous adenocarcinoma. Most of the tumors (90%) are of appendiceal origin from LAMN or HAMN associated with a mucocele [2]. Other tumors were mucinous adenocarcinomas of colonic [3], gastric [4], pancreatic [5, 6], urachian [7], pulmonary [8], endocervical [9] or mammary [10] origin, or to rare mucinous ovarian tumors, cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas [9]. Some authors reported non-neoplastic intra-peritoneal mucinous deposits caused by alternative processes as mucin retention due to a stercolith or a diverticule, or mucinous metaplasia of fallopian tubes [11,12,13], but such situations are very rare and questionable.

Physiopathologically, the mucin deposits in peritoneal cavity, more or less associated with tumor cells, are caused by the redistribution phenomenon [14] and epithelio-mesenchymal transition [15]. Hematogenic and lymphatic routes of dissemination seem to be infrequent in this complex pathology, still partially understood. However, because of its clinical evolution, PMP is considered as a neoplastic condition with variable behaviors, either indolent or aggressive.

Curative treatment of PMP relies on maximal cytoreduction surgery completed by HIPEC, performed by experienced staff in a reference center [16, 17]. This procedure is indeed associated with numerous potential complications, leading to high morbidity (16 to 65%) and mortality (0 to 18%). Nevertheless, extended survey is possible (59% at 5 years) [18].

Several histological classifications have been established for PMP. In 2017, Carr et al. proposed a PMP classification divided in four categories: mucin without epithelial cells; PMP with low-grade histological features; PMP with high-grade histological features; and PMP with signet ring cells [1]. Recently, the 2019 WHO (World Health Organization) classification adopted a three-tiered system of classification to unify and simplify denomination of the disease. Grade 1 (or low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm) is defined by acellular or hypocellular mucinous deposits, with pushing tumor margins, and low grade epithelial cell cytology. Grade 2 (or high grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm) is characterized by mucinous deposits with numerous epithelial cells often arranged in clusters with marked atypia. Grade 3 (or high grade with signet-ring cells) is represented by neoplasms containing true signet-ring cells defined as intracytoplasmic mucin vacuole indenting the nucleus (degenerating cells floating within mucin pools should not be considered as true signet-ring cells) [19].

The primitive ovarian origin of PMP has been debated for a long time. First descriptions of PMP were from appendiceal or intestinal origins. Thus, when a female patient presented with a clinical situation of PMP with both mucinous lesions of the appendix and the ovaries, she was considered to present either a PMP of appendiceal origin with secondary localization of the ovaries or an appendiceal PMP with a concomitant borderline mucinous ovarian tumor [20,21,22]. In order to elucidate the origin of PMP in cases of both appendiceal and ovarian mucinous lesions, some authors tried to define morphological criteria comparing the aspects of mucinous tumor of the ovaries with and without PMP and appendiceal tumor.

For Ronett et al., the secondary ovarian localization of a primitive digestive tumor was retained when (i) the ovarian tumor involved the surface with eventually superficial stroma; (ii) ovaries were of a quite normal size; (iii) a unilateral ovarian tumor had a digestive phenotype in a context of anteriority of such a digestive tumor; (iv) a bilateral ovarian tumor had a digestive phenotype without any known antecedent; (v) an appendiceal tumor was ruptured with an intact associated ovarian tumor [22].

Stewart et al. observed that secondary ovarian tumor was made by scalloped glands layered by sub epithelial clefts while primitive ovarian tumor did not share these features but was instead associated with an abundant stroma reaction and histiocytic infiltration [23].

Immunohistochemistry has also been used to distinguish between primary and secondary ovarian origin. Ferraira et al. showed that CK20 and MUC2 were more often expressed by mucinous ovarian tumors associated with PMP than by mucinous ovarian tumors without PMP, supporting the hypothesis of a secondary ovarian localization of a primitive digestive tumor [24]. Nevertheless, Saluja et al. reported a case of PMP associated with an ovarian borderline mucinous tumor without any digestive tumor [24]. In this case, the appendix was normal on full microscopic examination, and the ovarian tumor expressed both CK7 and CK20, with MUC2. Finally, studies revealed that the immunohistochemical profile of the tumor did not allow to distinguish between PMP of primitive ovarian or digestive origin, both of them being positive for CK20 and CDX2 with variable staining for CK7 [25].

O’Connell et al. investigated the mucin composition of PMP, which is principally made of MUC2 and MUC5AC and revealed that while MUC2 was more abundant in PMP, but also in appendiceal mucinous tumors and normal digestive tissue, MUC5AC was predominant in mucinous ovarian primitive tumors, suggesting that mucin composition could help to distinguish the origin of PMP [26, 27]. However, only a few studies on mucin composition are available.

Nonetheless, some cases of authentic PMP with an ovarian origin have been described. These cases were associated with various mucinous tumors of the ovary, as benign mucinous adenomas, borderline mucinous tumors and adenocarcinomas [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. In many of these primitive ovarian PMP, in which an appendiceal origin was formally excluded, mucinous ovarian tumors were associated with teratoma, leading some authors to consider that primitive ovarian origin of a PMP was only possible in a context of a mucinous ovarian tumor arising from an ovarian teratoma [36]. It should be noted that ovarian teratomas associated with mucinous tumors causing PMP did not show particularities from other teratomas without mucinous associated lesion, but such teratomatous component was often a minor part of the lesion. All the reported cases of primitive ovarian PMP associated with a teratoma in literature, from 2003 till 2021, have been listed in Table 1.

The unique and original feature of our case is that the primitive ovarian tumor responsible for the PMP was not a classic mucinous tumor of the ovary associated with a teratoma but a teratomatous appendiceal-like mucocele with LAMN. To our knowledge, such teratomatous involvement has never been described.

Molecular sequencing of PMP revealed frequent KRAS and GNAS mutations as in mucinous tumors of the appendix. These mutations are frequent in LAMN and HAMN and slightly rarer in mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinomas, which harbor frequent TP53 mutations as in HAMN but not LAMN [38]. KRAS mutations occur in exon 2. GNAS mutations are located at codon 201 in c.601 or c.602. Mutations in codon 601 are frequently c.601C > T, resulting in p.(R201C), and those in codon 602 are often c.602G > A resulting in p.(R201H) [39]. While the former is more common in LAMN, the latter is more common in HAMN. Molecular data on primitive mucinous ovarian carcinomas without the context of PMP showed frequent mutations in KRAS, without GNAS mutation [39]. Choi et al. studied molecular alterations in primitive ovarian mucinous tumor associated with teratoma and PMP. They revealed KRAS and GNAS associated mutations [36]. These results, as ours, could indicate that ovarian mucinous tumors associated with teratomas and responsible for PMP are in fact of a teratomatous digestive origin. Molecular data on PMP of other origins than appendiceal and ovarian are not available, because of their rarity.

Conclusions

PMP is a rare neoplastic disease, deriving in most cases from a mucinous appendiceal tumor from LAMN, HAMN or adenocarcinoma, all associated with co-KRAS and GNAS mutations. Mucinous tumors of other origins, mostly adenocarcinomas, can also cause PMP, among them mucinous ovarian tumors, almost always in a context of concomitant ovarian teratoma. In the literature, molecular data show that KRAS and GNAS co-mutations are also present in primitive ovarian PMP associated with teratoma.

By reporting here the presence of KRAS and GNAS mutations in this extremely rare case of primitive ovarian PMP derived from the rupture of a teratomatous appendiceal-like mucocele with LAMN arising in an ovarian teratoma, our results suggest the teratomatous digestive origin of the mucinous ovarian tumors causing PMP. This finding emphasizes the need to actively search for teratomatous signs in a context of primitive ovarian PMP.

Availability of data and materials

Concerning clinical and sample collection, approval was obtained according to the agreement of the tumor biobank of Rouen University Hospital (tissue sample collection n° DC2008–689).

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed Tomodensitometry

- HAMN:

-

High-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

- HIPEC:

-

Hyperthermic IntraPEritoneal chemotherapy

- LAMN:

-

Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PMP:

-

PseudoMyxoma Peritonei

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Carr NJ, Bibeau F, Bradley RF, Dartigues P, Feakins RM, Geisinger KR, et al. The histopathological classification, diagnosis and differential diagnosis of mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinomas and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Histopathology. 2017;6:847–58.

Van den Heuvel MG, Lemmens VE, Verhoeven RH, de Hingh IH. The incidence of mucinous appendiceal malignancies: a population-based study. Int J Color Dis. 2013;28:1307–10.

de Bree E, Witkamp A, Van De Vijver M, Zoetmulde F. Unusual origins of pseudomyxoma peritonei. J Surg Oncol. 2000;75(4):270–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/1096-9098(200012)75:4<270::AID-JSO9>3.0.CO;2-V.

Ikejiri K, Anai H, Kitamura K, Yakabe S, Saku M, Yoshida K. Pseudomyxoma peritonei concomitant with early gastric cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 1996;26(11):923–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00311797.

Chejfec G, Rieker WJ, Jablokow VR, Gould VE. Pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with colloid carcinoma of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 1986;90(1):202–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(86)90094-6.

Mizuta Y, Akazawa Y, Shiozawa K, Ohara H, Ohba K, Ohnita K, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei accompanied by intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2005;5(4-5):470–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000086551.

Agrawal AK. Bobin’ski P, Grzebieniak Z, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei originating from urachus: case report and review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(1):155–65. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.21.1695.

Kurita M, Komatsu H, Hata Y, Shiina S, Ota S, Terano A, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei due to adenocarcinoma of the lung: case report. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(3):344–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02358375.

Baratti D, Kusamura S, Milione M, Pietrantonio F, Caporale M, Guaglio M, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of extra-appendiceal origin: a comparative study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(13):4222–30. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5350-9.

Hawes D, Robinson R, Wira R. Pseudomyxoma peritonei from metastatic colloid carcinoma of the breast. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16(1):80–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01887311.

Lamps LW, Gray GF Jr, Dilday BR, Washington MK. The coexistence of low grade mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and appendiceal diverticula: a possible role in the pathogenesis of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(5):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880086.

Dupre MP, Jadavji I, Matshes E, Urbanski SJ. Diverticular disease of the vermiform appendix: a diagnostic clue to underlying appendiceal neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(12):1823–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.001.

Minguillon C, Friedmann W, Vogel M, Wessel J, Lichtenegger W. Mucinous metaplasia of fallopian tube mucous membrane as a cause of peusomyxoma peritonei. Zentralbl Pathol. 1992;138(5):363–5.

Sugarbaker PH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a cancer whose biology is characterized by a redistribution phenomenon. Ann Surg. 1994;219(2):109–11.

Bibi R, Pranesh N, Saunders MP, Wilson MS, O’dwyer ST, Stern PL, et al. A specific cadherin phenotype may characterize the disseminating yet non-metastatic behavior of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(9):1258–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603398.

Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery and peri-operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy as a curative approach to pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27(3):239–43.

Dartigues P, Isaac S, Villeneuve L, Glehen O, Capovilla M, Chevallier A, et al. Mise au point sur le pseudomyxome peritonéal. Aspects anatomo-pathologiques, et implications thérapeutiques. Ann Pathol. 2014;34(1):14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annpat.2014.01.012.

Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, Levine EA, Glehen O, Gilly FN, et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2449–56. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7166.

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76(2):2–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13975.

Young RH, Gilks CB, Scully RE. Mucinous tumors of the appendix associated with mucinous tumors of the ovary and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases supporting an origin in the appendix. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15(5):415–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199105000-00001.

Prayson RA, Hart WR, Petras RE. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with emphasis on site of origin and nature of associated ovarian tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(6):591–603.

Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ, Zahn CM, Shmookler BM, Jablonski KA, Kass ME, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women: a clinicopathologic analysis of 30 cases with emphasis on site of origin, prognosis and relationship to ovarian mucinous tumors of low malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1995;26(5):509–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0046-8177(95)90247-3.

Stewart CJ, Ardakani NM, Doherty DA, Young RH. An evaluation of the morphologic features of low-grade mucinous neoplasms of the appendix metastatic in the ovary, and comparison with primitive ovarian mucinous tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e318284e070.

Ferreira CR, Carvalho JP, Soares FA, Siquiera SA, Carvalho FM. Mucinous ovarian tumors associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei of adenomucinosis type: immunohistochemical evidence that they are secondary tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(1):59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00988.x.

Saluja M, Kenwright DN, Keating JP. Pseudomyxoma peritonei arising from a mucinous borderline ovarian tumor: case report and literature review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(4):399–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01189.x.

O’Connell JT, Hacker CM, Barsky SH. MUC2 is a molecular marker for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(9):958–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000026617.52466.9F.

O’Connell JT, Tomlinson JS, Roberts AA, McGonigle KT, Barsky SH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a disease of MUC2-expressing goblet cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(2):551–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64211-3.

Ronnett BM, Seidman JD. Mucinous tumors arising in ovarian mature cystic teraromas: relationship to the clinical syndrome of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):650–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200305000-00008.

Pranesh N, Menasce LP, Wilson MS, O’Dwyer ST. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: unusual origin from an ovarian mature cystic teratoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(10):1115–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2004.025148.

Marquette S, Amant F, Vergote I, Moerman P. Pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with a mucinous ovarian tumor arising from a mature cystic teratoma. A case report. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(4):340–3.

Stewart CJ, Tsukamoto T, Cooke B, Leung YC, Hammond IG. Ovarian mucinous tumor arising in mature cystic teratoma and associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei: report of two cases and comparison with ovarian involvement by low-grade appendiceal mucinous tumor. Pathology. 2006;38(6):534–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313020601024078.

Mandal S, Kawatra V, Khurana N. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma arising immature cystic teratoma ovary and associated pseudomyxoma peritonei: report of a case. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(3):265–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0579-6.

McKenney JK, Soslow RA, Longacre TA. Ovarian mature teratomas with mucinous epithelial neoplasms: morphologic heterogeneity and association with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(5):645–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815b486d.

Hwang JH, So KA, Modi G, Lee JK, Lee NW, Lee KW, et al. Borderline-like mucinous tumor arising in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28(4):376–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0b013e318191e766.

Mohtaram A, Boutayeb S, El Youbi MB, Sghiri T, Aaribi I, Kettani F, et al. Pseudomyxome péritonéal résultant d’un tératome ovarien associé à une tumeur mucineuse borderline : à propos d’un cas et revue de la littérature. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:156. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.14.156.2589.

Choi YJ, Lee SH, Kim MS, Jung SH, Hur SY, Chung YJ, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identified the genetic origin of a mucinous neoplasm in a mature cystic teratoma. Pathology. 2016;48(4):372–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2016.02.017.

Yan F, Shi F, Li X, Yu C, Lin Y, Li Y, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of pseudomyxoma peritonei originated from ovaries. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:7569–78. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S264474.

Nishikawa G, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Matsubara A, Mori T, Taniguchi H, et al. Frequent GNAS mutations in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. B J Cancer. 2013;108(4):951–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.47.

Nummela P, Saarinen L, Thiel A, Järvinen P, Lehtonen R, Lepistö A, et al. Genomic profile of pseudomyxoma peritonei analyzed using next-generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E282–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29245.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Nikki Sabourin-Gibbs (Rouen University Hospital) for assistance with language editing.

Funding

This work was not funded by any grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MCB and JCS performed histological examination of the left ovary and appendix. FB and AL realized molecular analyses. MCB and JCS were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Rouen University Hospital has approved this study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained according to the policies of the institutional review board of Rouen University Hospital and the French Ministry of Scientific Research.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Csanyi-Bastien, M., Blanchard, F., Lamy, A. et al. A case of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei of an unexpected origin. Diagn Pathol 16, 119 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01179-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01179-z