Abstract

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor of the uterine cervix with a well-documented link to infection with human papillomaviruses (HPV). According to a recent classification, there are several morphological variants of cervical squamous carcinoma, without reference to sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma, which is well described in other organs.

Case presentation

In this paper, we describe an extremely rare case of a 77-year-old woman with primary malignant cervical tumor displaying biphasic histomorphology with an epithelioid and sarcomatoid part; the latter was immunohistochemistry positive for cytokeratin and vimentin. The association with a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion and molecular proof of HPV33 infection in the tumor tissue supported our diagnosis of carcinoma with partial sarcomatoid differentiation.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of a primary cervical epithelial tumor with a partial sarcomatoid phenotype, an unequivocal HPV infection, and an associated precancerous lesion in the cervical mucosa. This is the first description of an HPV33 infection underlying a biphasic epithelioid-sarcomatous tumor of the uterine cervix. The terminology overlap between sarcomatoid carcinoma and carcinosarcoma is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common malignant tumor of the uterine cervix, whereas cervical cancer is the second or third most common malignancy in women worldwide [1]. The etiopathogenetic link to infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) and precursor squamous intraepithelial lesions in most cervical carcinomas are well known. The recent World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of gynecological tumors or Blaustein’s Monography [2] discerns several histomorphological variants of cervical SCC: keratinizing, non-keratinizing, basaloid, verrucous, warty/condylomatous, papillary, squamotransitional, and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. However, the WHO Classification does not describe the rare sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma (SSCC) even though it is described in the literature [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. In this paper, we report on the case of a rare SSCC of the uterine cervix with molecular proof of HPV33 infection.

Case presentation

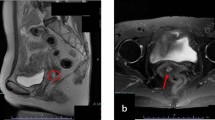

A 77-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the university hospital with vaginal bleeding that was occurring 30 years after menopause, and 45 years after her last gynecological examination. Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis revealed a hypoechogenic well-circumscribed endophytic tumor measuring 30 × 28 × 24 mm, almost filling the entire bulk of the anterior cervical labium (Fig.1). A biopsy excision from the tumor mass was performed. Microscopically, it was a neoplastic tissue with a solid architecture consisting of polymorphous tumor cells containing giant partly lobulated, multiple nuclei, and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. Immunohistochemistry was positive for pankeratin (cytokeratin) AE1/AE3, vimentin, and p16. These findings lead to a diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma. The patient underwent radical hysterectomy and adnexectomy (Wertheim-Meigs surgery) with pelvic lymphadenectomy, together with identification and frozen histological examinations of the sentinel lymph nodes.

The hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy specimens were sent for histopathological examination. Microscopically, an obviously malignant biphasic tumor, containing an epithelioid part with the morphology of invasive squamous non-keratinizing carcinoma and a polymorphous cell-rich component with abundant highly polymorphous, monstrous cells, with bizarre nuclear atypia and pleomorphism were observed (Fig.2). Immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3) was strongly positive for pankeratin (cytokeratin) AE1/AE3 in the epithelioid-squamous part and weaker but still unequivocally positive in the polymorphous part. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) was focally positive in both parts of the tumor. P63 and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMWK) were positive in the epithelioid-squamous component, while the polymorphous component was negative. The entire tumor showed strong diffuse p16 positivity. The polymorphous component was vimentin positive while the epithelioid-squamous part was vimentin negative. Proliferation activity (Ki67) was present in approximately 80% of the tumor cell nuclei. The expression of p53 was wild type. The rest of the markers tested, i.e., estrogenic and progesterone receptor, Wilms tumor-1 (WT-1), smooth muscle actin, desmin, myogenin, CD56, and ERG, were negative. Based on squamous morphology and p63 positivity, together with the spindle cell polymorphous component, which was cytokeratin positive, the diagnosis of SCC with sarcomatoid differentiation was confirmed. The tumor measured 27 × 24 × 24 mm. There was no involvement of the parametrium and no lymphatic or vascular invasion. Surgical resection margins were tumor-free. All 17 of the lymph nodes found in the lymphadenectomy specimen were free of metastatic involvement, including 2 sentinel lymph nodes. The sizable extent of the high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (HSIL/CIN3), affecting almost the entire exocervix and involving the exocervical resection margins, was an interesting ancillary finding. Immunohistochemistry on the HSIL showed strong diffuse p16 positivity.

Scans of histological slides stained with hematoxylin-eosin, showing biphasic malignant tumor of the uterine cervix, a squamous epithelioid part in the left, sarcomatoid part in the right, 7,1x b direct transition between sarcomatoid (up) and epithelioid (bottom) tumor components, 18,2x c detail of the sarcomatoid part with highly atypical spindle cells and bizarre cells, 52,7x, d and with necrosis, 53,2x

Scans of histological slides stained immunohistochemically. AE1/3 (11,2x): note the strong diffuse positivity in the epithelioid part of tumor (left) and weaker, but unequivocal diffuse positivity in the sarcomatoid part, in the upper right corner in detail (5,9x). EMA (7,8x): Note the heterogenous positivity in both epithelioid (left) and sarcomatoid (right) parts of the tumor. Vimentin (29,2x): note the strong positivity in the cervical stroma (left) and in the sarcomatoid part (right) and negativity in the accompanying HSIL (in the middle). P63 (11,2x): note the diffuse nuclear positivity in the epithelioid part (left) and negativity in the sarcomatoid tumor (right). HMWK (26,5x): note the positivity in the epithelioid tumor bud (in the middle) and full negativity in the sarcomatoid part. P16 (7,1x) note the strong and diffuse positivity in both parts of the tumor. Ki67 (16,6x): note the brisk proliferation activity in approximately 80% of tumor cells in both parts

Using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, we performed an additional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the HPV genes, using the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extracted from the tumor tissue, using primers amplifying the E6/E7 gene region and searching for HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, and 45. The PCR reaction found HPV type 33 in the extracted DNA.

Discussion

SSCC is a well-described variant of SCC in the lungs [3], the upper aerodigestive tract, and the skin, but rare in the uterine cervix [4]. SSCC is a primarily epithelial tumor composed of a squamous cell carcinoma element and a polymorphous sarcomatoid element derived from the squamous cell carcinoma element [3]. However, SSCC is not described in the recent WHO Classification of gynecological tumors. Kumar et al. (2008) reviewed only 16 cases [5]. From our point of view, the term SSCC overlaps to a significant extent with carcinosarcoma or malignant mixed Müllerian tumor (MMMT) of the uterine cervix, which is described in WHO as a very rare malignancy. There are more than 80 published cases of MMMTs of the uterine cervix [12]. Grayson et al. (2001) examined eight cases of uterine cervical carcinosarcomas (or MMMTs) and found an HPV-infection in all cases; in seven cases, it was found along with a squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) in the adjacent cervical epithelium [13], as in our case. Moreover, the authors documented cytokeratin-positivity in all eight tumors and EMA-positivity in the majority of the described cases, which was also similar to our case. Unlike Grayson et al., who found HPV type 16 in all cases, we found HPV type 33 in the DNA extracted from the tumor tissue. However, an infection with HPV16 was described in a single case of cervical SSCC as well [11].

Contrary to rare cervical MMMT or carcinosarcoma, MMMT of the uterine corpus is more common and has similar molecular and epidemiological characteristics to endometrial carcinoma, i.e., obesity and menopause [14], whereas uterine cervical MMMT and SSCC are HPV-related [11, 13]. Cervical MMMT differs in several ways from its much more common counterpart in the uterine corpus: the most common carcinomatous pattern in cervical MMMTs is a basaloid pattern that consists of anastomosing densely cellular trabeculae composed of small cells with scant cytoplasm and peripheral palisades; other epithelial patterns include typical squamous cell carcinoma. The sarcomatous element in MMMT is typically homologous and frequently has the appearance of a fibrosarcoma or endometrial stromal sarcoma [15]. Cervical MMMTs, compared to their counterparts in the corpus, are more commonly confined to the uterus at presentation, have a non-glandular epithelial component, and potentially have a better prognosis, whereas carcinosarcoma of the uterine corpus almost always has adenocarcinomatous component [16].

All considerations mentioned above lead us to the opinion that tumors of the uterine cervix with a concomitant epithelial and sarcomatous component are usually HPV-related and differ epidemiologically and histopathologically from corporal MMMT, independently of labeling them carcinosarcoma or sarcomatoid carcinoma. Due to the lack of a large dataset, it remains unclear, if the distinction between SSCC and cervical MMMT would have a clinical impact. According to the literature, cervical SSCC is quite an aggressive tumor [8]. From our point of view, the terminology overlap between cervical MMMT and SSCC may explain the paucity of literature surrounding SSCC. From our point of view, due to the unequivocal link with HPV infection, the term SSCC or SCC with sarcomatoid differentiation fits better than MMMT for this particular tumor; because of obviously squamous epithelial part of the tumor and well known relation between HPV and cervical SCC.

There are several theories about the potential histogenesis of biphasic malignant tumors of the female genital tract, including the “collision,” “combination,” “composition,” and “metaplastic” theories [13], which may be simplified to biclonal or monoclonal. Genetic studies [17,18,19] support the monoclonal origin of MMMTs from a common stem cell. Carcinosarcoma or sarcomatoid carcinoma may be regarded as an epithelial tumor originally in which a subclonal population has undergone a sarcomatoid transformation (or metaplasia): the common cytokeratin- and EMA-positivity of both the epithelial and sarcomatoid parts in our cases and other published cases may support this statement. The differential diagnosis between carcinosarcoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma remains rather an academic question; however, in the absence of definitive criteria, it’s etiological and morphological similarity to squamous carcinoma of the cervix leads us to prefer the term sarcomatoid carcinoma.

In conclusion, we report on an extremely rare case of primary cervical SSCC or carcinosarcoma (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage 1B1 associated with HPV 33 infection). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of HPV 33 in this type of tumor. The patient underwent adjuvant brachyradiotherapy, and five months after surgery, she is disease-free.

Availability of data and materials

It is not possible to share research data publicly.

Abbreviations

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EMA:

-

Epithelial membrane antigen

- FIGO:

-

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HMWK:

-

High-molecular-weight keratin

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- HSIL/CIN3:

-

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3

- MMMT:

-

Malignant mixed Müllerian tumor

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SIL:

-

Squamous intraepithelial lesion

- SSCC:

-

Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WT-1:

-

Wilms tumor-1

References

Stoler M, Bergeron C, Colgan TJ, Ferenczy AS, Herrington CS, Kim KR, et al. Squamous cell tumours and precursors. In: Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. Lyon: IARC; 2014. p. 176–81.

Pirog EC, Wright TC, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ. Carcinoma and other tumors of the cervix. In: Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, editors. Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract, 7th Edition. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2019. p. 316–38.

Terada T. Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282:231–2.

Rodrigues L, Santana I, Cunha T, Félix A, Freire J, Cabral I. Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21:287–9.

Kumar M, Bahl A, Sharma DN, Agarwal S, Halanaik D, Kumar R, Rath GK. Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: pathology, imaging, and treatment. J Cancer Res Ther. 2008;4:39–41.

Kong TW, Kim JH, Chang SJ, Ryu HS, Joo HJ. Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix successfully treated by laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:445–8.

Mohan H, Garg S, Handa U. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the cervix: case report of a rare entity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:571–3.

Brown J, Broaddus R, Koeller M, Burke TW, Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:23–8.

Pang LC. Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix with osteoclast like giant cells: report of two cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17:174–7.

Steeper TA, Piscioli F, Rosai J. Squamous cell carcinoma with sarcoma-like stroma of the female genital tract: Clinicopathologic study of four cases. Cancer. 1983;52:890–8.

Lin P, Ho CL, Shen MR, Huang LH, Chou CY. Evidence of human papilloma virus infection, enhanced phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein, and decreased apoptosis in sarcomatoid carcinoma of uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:336–40.

Comert KG, Turkmen O, Karalok A, Basaran D, Bulbul D, Turan T. Therapy modalities, prognostic factors, and outcome of the primary cervical carcinosarcoma: meta-analysis of extremely rare tumor of cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(9):1957–69.

Grayson W, Taylor LF, Cooper K. Carcinosarcoma of the uterine cervix: a report of eight cases with Immunohistochemical analysis and evaluation of human papillomavirus status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(3):338–47.

Zelmanowicz A, Hildesheim A, Sherman ME, Sturgeon SR, Kurman RJ, Barrett RJ, et al. Evidence for a common etiology for endometrial carcinomas and malignant mixed mullerian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69:253–7.

Wright TC, Ferenczy A, Kurman RJ. Carcinoma and other tumors of the cervix. In: Kurman RJ (Ed.), Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract, 5th Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, New York, Heidelberg, 2002. Pp. 346–371.

Clement PB, Zubovits JT, Young RH, Scully RE. Malignant mullerian mixed tumors of the uterine cervix: a report of nine cases of a neoplasm with morphology often different from its counterpart in the corpus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998;17:211–22.

Kounelis S, Jones MW, Papadaki H, Bakker A, Swalsky P, Finkelstein SD. Carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed mullerian tumors) of the female genital tract: comparative molecular analysis of epithelial and mesenchymal components. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:82–7.

Leskela S, Pérez-Mies B, Rosa-Rosa JM, Cristobal E, Biscuola M, Palacios-Berraquero ML, Ong S, Matias-Guiu Guia X, Palacios J. Molecular basis of tumor heterogeneity in endometrial carcinosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(7):964.

Sreenan JJ, Hart WR. Carcinosarcomas of the female genital tract: a pathologic study of 29 metastatic tumors: further evidence for the dominant role of the epithelial component and the conversion theory of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:666–74.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special thanks to Mr. Tom Secrest, MSc. for his valuable language editing service. This work was supported by the Charles University research program PROGRES Q 28 (Oncology). The fund covers all institution publications related to oncology. In our article, the fund covered some of the antibodies used in immunohistochemistry and publication expenses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH analyzed and interpreted the patient’s data, performed the histological examination, formulated the final diagnosis after resection, took the pictures, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. BR performed the histological examination and formulated the presented diagnosis from the biopsy and contributed to writing the manuscript. MH analyzed and interpreted the patient’s clinical data and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hrudka, J., Rosová, B. & Halaška, M.J. Squamous cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation or carcinosarcoma of the uterine cervix associated with HPV33 infection: report of a rare case. Diagn Pathol 15, 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-00934-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-00934-y