Abstract

Background

To evaluate the clinical utility of LIM Domain Only 2 (LMO2) negative and CD38 positive in diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma (BL).

Methods

LMO2 and CD38 expression determined by immunohistochemistry in 75 BL, 12 High-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS (HGBL,NOS) and 3 Burkitt-like lymphomas with the 11q aberration.

Results

The sensitivity and specificity of LMO2 negative for detecting BL were 98.67 and 100%, respectively; those of CD38 positive were 98.67 and 66.67%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of a combination of both for detecting BL were 97.33 and 100%, respectively. In our study, the combined LMO2 negative and CD38 positive results had a higher area under the curve than either LMO2 negative or CD38 positive alone.

Conclusions

A combination of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive is useful for the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is one of the most studied human malignant tumors that originates in the B cells. Although it is relatively simple to diagnosis BL in children, it is a challenge to identify reliable subtypes of aggressive B-cell lymphoma in adults [1, 2]. It is crucial to distinguish BL from other lymphomas because of its rapid progress and the planned improvements in treatment for adult aggressive B-cell lymphomas [1,2,3,4].

BL is a highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma with unique morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features [5]. BL tumor cells are monomorphic, composed of medium-sized cells with round nuclei, multiple deeply stained nucleoli, and basophilic cytoplasm. The cell proliferation rate as well as the apoptotic rate are extremely high. Approximately 100% of the cells are Ki-67 positive (MIB-1 positive) and display the “starry sky” pattern. BL has a typical immunophenotype-strong immunoglobulin (Ig) expression and generally expresses markers of B cell-associated antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79a) and a germinal center (CD10). It does not express BCL-2 [6]. In nearly all studies, BL was associated with one of three chromosomal translocations on the c-MYC oncogene locus (8q24) and the Ig gene on the long arm of chromosome 14, also the immunoglobulin light chain genes on chromosomes 2 and 22 [7,8,9].

High-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS includes blastoid-appearing large B-cell lymphomas and cases lacking MYC and BCL2 or BCL6 translocations. HGBL, with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 and HGBL, NOS replaces the 2008 category of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BCLU) [5]. Most morphologic features are intermediate between those of DLBCL and BL, with a high proliferative index and starry sky pattern, and the immunophenotype is consistent with that of BL.

Burkitt-like lymphoma with an 11q aberration has morphologic and immunophenotypic features similar to those of BL, but lacks MYC rearrangement and has the typical 11q aberration, which appears as a partial amplification and partial deletion in the region at the same time [10]. The tumor is rare, accounting for only 3% of BL, is more common in children and young people and more in males than females, and is more likely to involve lymph nodes than BL [11].

The above lymphomas are difficult to distinguish from their histological morphologies and existing routine immunophenotypes. Our study hopes to discover new immunohistochemical markers and analyze their expressions in these lymphomas so as to better diagnosis of BL.

LMO2 is a transcription factor that plays an important role in embryonic development and angiogenesis. Studies have shown that many tumors have LMO2 expression and that it is associated with the prognosis for patients with certain tumors, such as glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer [12, 13]. In the lymphatic and hematopoietic system, in addition to expression in the normal lymphoid germinal center, LMO2 is expressed in germinal center-derived lymphomas, acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [14]. Recent studies have found that LMO2 protein expression is downregulated or negative in BL with abnormal MYC [2]. CD38 is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein that has several complex and unique biological characteristics and functions. It is widely expressed in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells, including bone marrow precursor cells, germinal center B-cells, plasma cells, prostate epithelial cells, skeletal muscle, and other tissues, and in activated T cells, B cells, monocytes, NK cells, and islet cells [15]. CD38 is strongly expressed in both plasma cells and plasma cell tumors. It is also present in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [16, 17]; however, no in-depth studies have been conducted to verify the positive expression of CD38 in BL.

Our study analyzed the expression of LMO2 and CD38 proteins in BL, HGBL,NOS and Burkitt-like lymphomas with the 11q aberration and hypothesized that the combination of LMO2-negative and CD38-positive expressions can be used to diagnose auxiliary BL. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the specificity and sensitivity of LMO2-negative, CD38-positive, and the combination of both expressions, as well as their diagnostic efficiency in BL.

Materials and methods

Case selection

From May 2015 to March 2018, we compiled 75 cases of BL, 12 cases of HGBL, NOS and 3 cases of Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration from the Department of Pathology in Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, China. All cases were classified according to the diagnostic criteria of the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. None of the patients received any treatment and all had complete pathological data. The study was retrospectively performed and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (2018-P2–130-01).

Immunohistochemistry

All samples were fixed with 3.7% neutral formaldehyde, followed by routine paraffin section and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Proteins CD38 (clone 38CO3), CD10 (clone MX002), BCL-6 (clone LN22), BCL-2 (clone SP66), MUM1 (clone MUM1p), c-Myc (clone Y69), Ki67 (clone MIB-1), their reagents, and their primary antibodies were purchased from the Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnologies Development Company (Maixin, Fuzhou, China).

The conditions and the evaluation of all these antibodies were the same as those previously described and were assessed following the recommended guidelines for their interpretation by the Luneburg Lymphoma Biomarker Consortium; appropriate internal controls were used in the evaluation of the immunostains [18, 19]. c-Myc, CD38, and Ki67 immunostaining were also semiquantitatively evaluated, and the cutoff rates for positive results were 80, 80, and 90% [2], respectively.

LMO2 was studied using clone 1A9–1 (Ventana,Roche, Tucson, AZ), which was detected using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) in the BenchMark XT automated immunostainer (Ventana). LMO2 immunostaining was evaluated following the cutoff criteria by Natkunam et al. [14], and in which staining of > 30% of the lymphoma cells was designated as positive for LMO2.

Brownish-yellow nuclear particles were observed in cells staining positive for LMO2 and c-Myc. Cells were defined as CD38 positive when the cell membrane stained brownish yellow.

Detection using fluorescence in situ hybridization

FISH was conducted using the ATM dual color probe (LBP Medicine Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). ATM (11q22.3) was marked in red, and the CEP11 (11p11–q11) chromosomal probe was labeled in green. In addition, the MYC break apart probe (Beijing GPmedical Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to detect MYC status. The specific operations were conducted according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Statistical analyses

Staining sensitivity and specificity for LMO2 and CD38 with 95% exact binomial confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated. Our immunostaining criteria for diagnosing BL were positive staining for CD38 and negative staining for LMO2.

Data were compared using the χ2 test, unpaired t-tests, or nonparametric tests, when necessary. P < .05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. The differences between rates were tested using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, when appropriate.

Logistic regression was used to model BL as a function of immunostaining. The corresponding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for different combinations of immunostains, and the areas under these correlated ROC curves (AUCs) were compared using the nonparametric approach of DeLong et al. and integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI) [20, 21]. All analyses were performed using SPSS v 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc v 9.2.1.0 (https://www.medcalc.org/).

Results

Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features

The clinicopathological features and the expression of immunohistochemical markers in 75 cases of BL, 12 cases of HGBL,NOS and 3 cases of Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration are shown in Table 1.

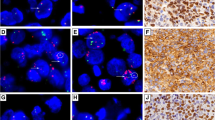

Of the 75 cases of BL, 62 were males, and patient ages ranged from 2 to 69 years with a median age of 10 years. Of the 75 BL cases, 27 involved lymph nodes and 48 were extranodal. Morphologically, the tumors consisted of sheets of a monotonous population of tumor cells with diffuse infiltration. They were closely packed, medium sized, had small or medium amounts of cytoplasm, were lightly stained, contained a round nucleus, exhibited a coarse chromatin pattern, and contained two to four small nucleoli within each nucleus. A large number of nuclear divisions were observed within the tumor, and a large number of dead neoplastic cells that were swallowed by macrophages to form a “starry sky” phenomenon (Fig. 1a, b) were also observed. Of the 75 cases of BL, 74 (98.67%) were negative for LMO2 and positive for CD38. The expression rates of CD10+, BCL-6+, BCL-2-, MUM-1+, c-Myc (80%+), and Ki67 (95%+) were 73/75 (97.33%), 73/75 (97.33%), 67/75 (89.33%), 42/75 (56%), 67/75 (89.33%), and 64/75 (85.33%), respectively. The BL tumor cells were generally negative for LMO2, but were strongly and diffusely cell membrane positive for CD38, and ≥ 80% of tumor cells were strongly nuclear positive for c-Myc (Fig. 1c-e).

Seven of the 12 patients with HGBL,NOS were males. Patient ages ranged from 1 to 67 years with a median age of 31 years. Four cases involved lymph nodes and eight were extranodal. Morphologically, these gray areas or borderline cases were characterized by medium-size cells that were similar to those in BL and mixed with some of the large cells typically seen in DLBCL (Fig. 2a, b). All 12 cases showed 100% (12/12) expression of LMO2. Four (4/12) cases (33.3%) were positive for CD38. The expression rates of CD10+, BCL-6+, BCL-2-, MUM-1+, c-Myc (80%+), and Ki67 (95%+) were 11/12 (91.67%), 11/12 (91.67%), 10/12 (83.33%), 4/12 (33.33%), 5/12 (41.67%), and 8/12 (66.67%), respectively. In HGBL, LMO2 was found in moderate intensity in the nucleus, CD38 was not expressed or was weakly expressed in the tumor cells, and c-Myc was detected in some tumor cell nuclei (Fig. 2c-e).

One of the three patients with Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration was male. The age of the three patients was 10, 15 and 22 years respectively. One case involved lymph nodes and two were extranodal. Morphologically, the tumors were very similar to those of BL, appearing as diffusely growing, medium-sized lymphocytes with uniform cells. There were multiple deviated small nucleoli scattered within the tingible body macrophages to form a starry sky phenomenon (Fig. 3a, b). All three cases were LMO2 negative and CD38 positive (100%). The expression rates of CD10+, BCL-6+, BCL-2-, MUM-1+, c-Myc (80%+), and Ki67 (95%+) were 3/3 (100%), 3/3 (100%), 2/3 (66.67%), 2/3 (66.67%), 2/3 (66.67%), and 2/3 (66.67%), respectively. In Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration, the expression patterns of LMO2, CD38, and c-Myc in the tumor cells were similar to those in BL tumor cells (Fig. 3c-e).

FISH detection results

In BL, c-MYC translocation showed one red signal, one green signal, and one fused yellow signal in the nucleus (Fig.1f). In HGBL,NOS showed MYC nonrearranged (Fig. 2f). In the Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration, the MYC gene break apart FISH probe did not detect breakpoints in MYC. When the ATM dual color probe was used, ATM (11q22.3) was marked red and the CEP11 (11p11-q11) chromosomal probe was marked green. The results showed that ATM was amplified (three red, two green) (Fig. 3f).

Statistical analyses of immunohistochemical expression in BL and HGBL, NOS

There were significant differences in the expression of the three immunophenotypes LMO2 negative, CD38 positive, and c-Myc (80%+) in the 75 cases of BL and 12 cases of HGBL, NOS(P < .01) (Table 2).

Sensitivity and specificity of immunostaining combinations

The sensitivities (95%CI) of tissues staining LMO2 negative, CD38 positive, and a combination of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive were 98.67, 98.67, and 97.33%, respectively. The corresponding specificities (95%CI) were 100, 66.67, and 100%, respectively (Table 3). The ROC curves for the immunohistochemistry markers were analyzed by logistic regression. The AUC (95%CI) for tissues staining LMO2 negative, CD38 positive, and a combination of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive were 0.993, 0.827, and 0.998, respectively (Table 3).

Comparison of the diagnostic efficacy between combination of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive and single index

A significant difference existed between ROC curves for tissues staining LMO2 negative and CD38 positive compared with those staining CD38 positive (P = .015); however, there was no significant difference observed between those staining LMO2 negative and those staining both LMO2 negative and CD38 positive (P = .328) (Table 4). The same results can be obtained by integrated discrimination improvement index analysis (Table 4).

Discussion

BL is a highly aggressive B-cell NHL characterized by the translocation and dysregulation of c-MYC on chromosome 8 [2]. Researchers have questioned whether c-MYC rearrangement is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of BL and have found that ≤5% of the tumors with typical BL characteristics do not have c-MYC rearrangement [1, 22]. Some researchers have speculated that these cases might have molecular pathogeneses other than the MYC activation mechanism, which is the BL’s iconic pathogenesis. Recently, many studies have reported cases with clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, or gene expression characteristics consistent with BL, but lacked FISH-detected positive MYC rearrangement. Additional studies have found that there were 11q aberrations in MYC-negative cases [10, 11, 23]; therefore, the 2016 revision of WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues proposed a new temporary type of lymphoma-Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration [5].

BL, HGBL,NOS and Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration can be diffusely infiltrated by large, medium-sized lymphocytes, no obvious nodule formation, monotonous and consistent cells, and a starry sky pattern. In addition to the expression of B-cell markers, all tumors showed mostly the expression of CD10 positive, BCL-6 positive, and BCL-2 negative in the immunophenotype; therefore, these types of tumors cannot be fully identified using only their morphology and the immunophenotype.

Previous studies have found that LMO2 has high sensitivity and specificity of expression in normal germinal center B cells and germinal center B cell-derived lymphomas. LMO2 was also expressed in myeloid and erythroid progenitor cells, megakaryocytes, lymphocytes, and acute myeloid leukemia. It was rarely expressed in mature T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, or plasma cell tumors. In addition, with the exception of endothelial cells, it did not express in non-lymphoid hematopoietic tissue. In DLBCL, the expression profile of LMO2 was similar to that of other germinal center-related proteins (HGAL, BCL6, and CD10), but was different from nongerminal center proteins (MUM1/IRF4 and BCL2) [14]. Recent studies have found that LMO2 might be a useful indicator for identifying MYC translocation and might also help identify BL [24].

We observed that the deletion of LMO2 expression might be particularly helpful in diagnosing BL. In this series, we found 74 of the 75 BL cases studied were negative for LMO2 using a cutoff of 30%. This was consistent with the data obtained using the GEP study, which indicated that the expression level of LMO2 was lower in BL [1, 2]. Only three studies analyzed the expression of the LMO2 protein in a small number of BL cases. Natkunam and colleagues and Agostinelli and colleagues defined two different cloned LMO2 proteins and evaluated the specificity and effectiveness of their antibodies. In these two studies, the expression rate of LMO2 in BL was 5/10 (50.0%) and 13/32 (41.0%), respectively, and 1/3 (33.3%) in the BL cell line (Ramos cell line). A third study comprised five cases of BL, and LMO2 was expressed in only one case (20%) [14, 25, 26]. Previous studies have also found that the presence of LMO2 protein can distinguish BL from DLBCL [25], because it was more commonly expressed in the latter [26]. In our study, we found that LMO2 protein was 100% positively expressed in HGBL; however, it was only expressed in one of Seventy-five Burkitt lymphomas. There was a statistically significant difference in the negative expression of LMO2 protein between BL and HGBL,NOS(P < .01). The sensitivity and specificity of the negative expression of LMO2 protein were 98.67 and 100%, respectively, and AUC of diagnostic efficiency was 0.993; therefore, we preliminarily concluded that LMO2 deletion might play a role in BL identification. None of the previous studies found a correlation between LMO2 and MYC rearrangements; however, a recent study not only found low expression of LMO2 in BL, but also 100% detected MYC rearrangement. This study suggested that the loss of LMO2 might be a good predictor of the presence of MYC [24]. In MYC rearrangement in BL, the exact mechanism that leads to LMO2 downregulation was not clear; however, Natkunam et al. [14] found that LMO2 protein is highly expressed at the mRNA level in the Ramos cell line, whereas the expression was indeed low at the immunohistochemical protein level. This suggested that LMO2 might be regulated at the posttranscriptional level in BL. These findings suggested that LMO2 protein can be used as an alternative marker for detecting MYC translocation in BL and might have application value in the differential diagnosis of other high-grade lymphomas.

CD38 is a transmembrane glycoprotein and in addition to marking mature plasma cells and plasma cell tumors, is a marker for germinal center B-cells [15]. Previous studies have found that CD38 is positively expressed in BL, but no in-depth studies have been conducted to verify this [27]. The expression of CD38 in HGBL,NOS and Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration was even more limited. In our study, the positive rates of CD38 in BL, HGBL,NOS and Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration were 98.67 (74/75), 33.3 (4/12), and 100% (3/3), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the positive expression rate of CD38 in BL and HGBL,NOS (P < .01). The sensitivity and specificity of the positive expression of CD38 protein were 98.67 and 66.67%, respectively, and AUC of diagnostic efficiency was 0.827. Previous studies have found that CD38, as LMO2, can be considered as a valuable diagnostic marker for identifying BL/DLBCL [28]. At the immunohistochemical level, it has been found that CD38 and CD44 can be used to distinguish between MYC-positive and MYC-negative lymphomas [29]. In the absence of cytogenetic analysis, it was very difficult to identify MYC-R in high-grade B-cell lymphomas. In practice, classical morphologic features of starry sky with medium-sized lymphocytes, typical Ki-67 hyperproliferation/CD10+/bcl-6+/bcl-2-, and recently identified CD38+/CD44−/TCL-1+ can predict a great possibility of MYC-R [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. All of these suggest that CD38 has a specific value in the differential diagnosis of BL.

Recent studies have suggested that the expression of MYC protein in aggressive B-cell lymphoma can effectively predict a poor prognosis [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. MYC protein is significantly correlated with MYC rearrangement, but the expression of MYC protein is not necessarily the result of MYC rearrangement [41]. In our study, the cutoff value of the positive expression of MYC protein was defined as 80% because of the differential diagnosis of BL, which was not consistent with previous studies [19, 35]. There was a significant difference in the expression of MYC protein in BL and HGBL,NOS (P < .01; Table 2) because of the defined MYC protein cutoff value. Because of the impact on the statistics of the defined MYC protein–positive cutoff value, we excluded MYC in subsequent statistical analyses. Finally, the combination of LMO2-negative and CD38-positive was used in the differential diagnosis of BL in our study. The sensitivity and specificity of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive were 97.33 and 100%, respectively, and AUC of diagnostic efficiency was 0.998, which was larger than AUC of those only LMO2 negative (0.993) or only CD38 positive (0.827). Further analysis found that AUC of the combination of LMO2-negative and CD38-positive was statistically different (P = .015) from that of CD38 positive, and there was no statistical difference (P = .328) in AUC of the combination of LMO2-negative and CD38-positive compared with that of LMO2 negative. The same results can be obtained by integrated discrimination improvement index analysis. The reasons for this were that first, the sample size of our study was relatively small, and in a follow-up study we will need to increase the sample size to reduce sampling error. Second, Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration was rare; therefore, only three cases were included in our study and the expressions of LMO2 and CD38 in those cases were consistent with that in BL. We did not include these three cases in the statistical analyses shown in Table 2. Further analyses with a larger sample must be conducted to assess whether the expressions of LMO2 and CD38 in Burkitt-like lymphoma with the 11q aberration is completely identical to those in BL.

There was another limitation in our study. The best detection method for the 11q aberration is the chip technology of comparative genomic hybridization using oligonucleotide microarrays. In this study, ATM detected by FISH was located in 11q22. There were eight cases in the literature that reported amplification of this gene region [10, 11, 23], which was similar to the results of our study; therefore, the detection of this gene indirectly proved the 11q aberration.

Conclusions

We believe that the assessment of LMO2 and CD38 protein expression can improve the accuracy of the pathological diagnosis of BL. At the same time, with the use of routine immune indices, such as immunohistochemical markers CD10 and BCL2, the combination of LMO2-negative and CD38-positive results can be directly applied to the routine assessment of BL in clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

Is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BL:

-

Burkitt lymphoma

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HGBL, NOS:

-

High-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS

- IDI:

-

Integrated discrimination improvement index

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Hummel M, Bentink S, Berger H, Klapper W, Wessendorf S, Barth TF, et al. A biologic definition of Burkitt's lymphoma from transcriptional and genomic profiling. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2419–30.

Mead GM, Barrans SL, Qian W, Walewski J, Radford JA, Wolf M, et al. A prospective clinicopathologic study of dose-modified CODOX-M/IVAC in patients with sporadic Burkitt lymphoma defined using cytogenetic and immunophenotypic criteria (MRC/NCRI LY10 trial). Blood. 2008;112(6):2248–60.

Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW, Lam LT, Kluin P, Boerma EJ, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2431–42.

Molyneux EM, Rochford R, Griffin B, Newton R, Jackson G, Menon G, et al. Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1234–44.

Cazzola M. Introduction to a review series: the 2016 revision of the WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Blood. 2016;127(20):2361–4.

Dunleavy K, Little RF, Wilson WH. Update on Burkitt lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(6):1333–43.

Salaverria I, Siebert R. The gray zone between Burkitt's lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma from a genetics perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(14):1835–43.

Boxer LM, Dang CV. Translocations involving c-myc and c-myc function. Oncogene. 2001;20(40):5595–610.

Hecht JL, Aster JC. Molecular biology of Burkitt's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(21):3707–21.

Salaverria I, Martin-Guerrero I, Wagener R, Kreuz M, Kohler CW, Richter J, et al. A recurrent 11q aberration pattern characterizes a subset of MYC-negative high-grade B-cell lymphomas resembling Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123(8):1187–98.

Ferreiro JF, Morscio J, Dierickx D, Marcelis L, Verhoef G, Vandenberghe P, et al. Post-transplant molecularly defined Burkitt lymphomas are frequently MYC-negative and characterized by the 11q-gain/loss pattern. Haematologica. 2015;100(7):e275–9.

Nakata K, Ohuchida K, Nagai E, Hayashi A, Miyasaka Y, Kayashima T, et al. LMO2 is a novel predictive marker for a better prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia. 2009;11(7):712–9.

Kim SH, Kim EJ, Hitomi M, Oh SY, Jin X, Jeon HM, et al. The LIM-only transcription factor LMO2 determines tumorigenic and angiogenic traits in glioma stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(9):1517–25.

Natkunam Y, Zhao S, Mason DY, Chen J, Taidi B, Jones M, et al. The oncoprotein LMO2 is expressed in normal germinal-center B cells and in human B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2007;109(4):1636–42.

van de Donk N, Richardson PG, Malavasi F. CD38 antibodies in multiple myeloma: back to the future. Blood. 2018;131(1):13–29.

Bras AE, Beishuizen A, Langerak AW, Jongen-Lavrencic M, Te Marvelde JG, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, et al. CD38 expression in paediatric leukaemia and lymphoma: implications for antibody targeted therapy. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(2):292–6.

van de Donk NW, Janmaat ML, Mutis T, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Ahmadi T, Sasser AK, et al. Monoclonal antibodies targeting CD38 in hematological malignancies and beyond. Immunol Rev. 2016;270(1):95–112.

de Jong D, Xie W, Rosenwald A, Chhanabhai M, Gaulard P, Klapper W, et al. Immunohistochemical prognostic markers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: validation of tissue microarray as a prerequisite for broad clinical applications (a study from the Lunenburg lymphoma biomarker consortium). J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(2):128–38.

Valera A, López-Guillermo A, Cardesa-Salzmann T, Climent F, González-Barca E, Mercadal S, et al. MYC protein expression and genetic alterations have prognostic impact in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Haematologica. 2013;98(10):1554–62.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–45.

Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, Hanna S, Iorio A, Devereaux PJ, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: Users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1377–84.

Haralambieva E, Schuuring E, Rosati S, van Noesel C, Jansen P, Appel I, et al. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization for detection of 8q24/MYC breakpoints on routine histologic sections: validation in Burkitt lymphomas from three geographic regions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40(1):10–8.

Pienkowska-Grela B, Rymkiewicz G, Grygalewicz B, Woroniecka R, Krawczyk P, Czyz-Domanska K, et al. Partial trisomy 11, dup(11)(q23q13), as a defect characterizing lymphomas with Burkitt pathomorphology without MYC gene rearrangement. Med Oncol. 2011;28(4):1589–95.

Colomo L, Vazquez I, Papaleo N, Espinet B, Ferrer A, Franco C, et al. LMO2-negative expression predicts the presence of MYC translocations in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(7):877–86.

Agostinelli C, Paterson JC, Gupta R, Righi S, Sandri F, Piccaluga PP, et al. Detection of LIM domain only 2 (LMO2) in normal human tissues and haematopoietic and non-haematopoietic tumours using a newly developed rabbit monoclonal antibody. Histopathology. 2012;61(1):33–46.

Menter T, Gasser A, Juskevicius D, Dirnhofer S, Tzankov A. Diagnostic utility of the germinal center-associated markers GCET1, HGAL, and LMO2 in Hematolymphoid neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23(7):491–8.

Barth TF, Müller S, Pawlita M, Siebert R, Rother JU, Mechtersheimer G, et al. Homogeneous immunophenotype and paucity of secondary genomic aberrations are distinctive features of endemic but not of sporadic Burkitt's lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement. J Pathol. 2004;203(4):940–5.

Naresh KN, Ibrahim HA, Lazzi S, Rince P, Onorati M, Ambrosio MR, et al. Diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma using an algorithmic approach--applicable in both resource-poor and resource-rich countries. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(6):770–6.

Rodig SJ, Vergilio JA, Shahsafaei A, Dorfman DM. Characteristic expression patterns of TCL1, CD38, and CD44 identify aggressive lymphomas harboring a MYC translocation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(1):113–22.

Cogliatti SB, Novak U, Henz S, Schmid U, Möller P, Barth TF, et al. Diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma in due time: a practical approach. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(3):294–301.

Haralambieva E, Boerma EJ, van Imhoff GW, Rosati S, Schuuring E, Müller-Hermelink HK, et al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, and genetic analysis of adult lymphomas with morphologic features of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(8):1086–94.

McClure RF, Remstein ED, Macon WR, Dewald GW, Habermann TM, Hoering A, et al. Adult B-cell lymphomas with burkitt-like morphology are phenotypically and genotypically heterogeneous with aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(12):1652–60.

Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C, Barth TF, Bernd HW, Feller AC, et al. MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(12):2253–63.

Green TM, Young KH, Visco C, Xu-Monette ZY, Orazi A, Go RS, et al. Immunohistochemical double-hit score is a strong predictor of outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3460–7.

Johnson NA, Slack GW, Savage KJ, Connors JM, Ben-Neriah S, Rogic S, et al. Concurrent expression of MYC and BCL2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3452–9.

Green TM, Nielsen O, de Stricker K, Xu-Monette ZY, Young KH, Møller MB. High levels of nuclear MYC protein predict the presence of MYC rearrangement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(4):612–9.

Tapia G, Lopez R, Muñoz-Mármol AM, Mate JL, Sanz C, Marginet R, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of MYC protein correlates with MYC gene status in aggressive B cell lymphomas. Histopathology. 2011;59(4):672–8.

Cook JR, Goldman B, Tubbs RR, Rimsza L, Leblanc M, Stiff P, et al. Clinical significance of MYC expression and/or "high-grade" morphology in non-Burkitt, diffuse aggressive B-cell lymphomas: a SWOG S9704 correlative study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(4):494–501.

Lynnhtun K, Renthawa J, Varikatt W. Detection of MYC rearrangement in high grade B cell lymphomas: correlation of MYC immunohistochemistry and FISH analysis. Pathology. 2014;46(3):211–5.

Perry AM, Alvarado-Bernal Y, Laurini JA, Smith LM, Slack GW, Tan KL, et al. MYC and BCL2 protein expression predicts survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(3):382–91.

Chisholm KM, Bangs CD, Bacchi CE, Molina-Kirsch H, Cherry A, Natkunam Y. Expression profiles of MYC protein and MYC gene rearrangement in lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):294–303.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province, China (No. WSN-059), Scientific Research Topic of Jiangsu Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission, China (No. H201626), Key Talents of Medical Science in Jiangsu Province, China (No. QNRC2016682). National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81602010), Key Scientific and Technological Projects in Nantong City, Jiangsu, China (No. MS22018001), and Jiangsu Post-doctoral Foundation Research Project, China (No. 2019Z142). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL, TB designed the study, performed the evaluation of the IHC stains, participated in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. YZ, YZ and JZ participated in data analysis. XZ and JX provided tissue specimens. YL financed the study and participated in evaluation of the IHC stains. All authors reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate was given by all patients in writing (ethics approval was given by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, China, 2018-P2–130-01).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Bian, T., Zhang, Y. et al. A combination of LMO2 negative and CD38 positive is useful for the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma. Diagn Pathol 14, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0876-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0876-3