Abstract

Background

Because little is known about food insecurity in people with mental health conditions, we investigated relationships among food insecurity, nutrient intakes, and psychological functioning in adults with mood disorders.

Methods

Data from a study of adults randomly selected from the membership list of the Mood Disorder Association of British Columbia (n = 97), Canada, were analyzed. Food insecurity status was based on validated screening questions asking if in the past 12 months did the participant, due to a lack of money, worry about or not have enough food to eat. Nutrient intakes were derived from 3-day food records and compared to the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs). Psychological functioning measures included Global Assessment of Functioning, Hamilton Depression scale, and Young Mania Rating Scale. Using binomial tests of two proportions, Mann–Whitney U tests, and Poisson regression we examined: (1) food insecurity prevalence between the study respondents and a general population sample from the British Columbia Nutrition Survey (BCNS; n = 1,823); (2) differences in nutrient intakes based on food insecurity status; and (3) associations of food insecurity and psychological functioning using bivariate and Poisson regression statistics.

Results

In comparison to the general population (BCNS), food insecurity was significantly more prevalent in the adults with mood disorders (7.3% in BCNS vs 36.1%; p < 0.001). Respondents who were food-insecure had lower median intakes of carbohydrates and vitamin C (p < 0.05). In addition, a higher proportion of those reporting food insecurity had protein, folate, and zinc intakes below the DRI benchmark of potential inadequacy (p < 0.05). There was significant association between food insecurity and mania symptoms (adjusted prevalence ratio = 2.37, 95% CI 1.49–3.75, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Food insecurity is associated with both nutritional and psychological health in adults with mood disorders. Investigation of interventions aimed at food security and income can help establish its role in enhancing mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among health researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and decision makers, there are concerns about the growing global and ethical issue of food insecurity [1], defined as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable food in socially acceptable ways [2]. The impact of food insecurity on mental health is significant and may be attributed to its associations with suboptimal diet [3–5], and psychological issues such as depression, eating disorders, and impaired cognition [6–9]. Of the few investigations that have examined food insecurity in populations with confirmed diagnosis of a mental health condition, results have indicated an association with food insufficiency [10] and that patients in a psychiatric emergency unit who lacked food security had higher levels of psychological distress compared to food-secure individuals [11]. In a previous study of the determinants of food intakes in a sample of adults with confirmed mood disorders conducted by the authors [12], a high prevalence of inadequate intakes of several micronutrients (e.g., folate, vitamin B12, iron, zinc) was found. As part of this investigation, the authors also included food insecurity screening questions and measures of psychological symptoms, as it was speculated that food access would be associated with both dietary intake and mental function in this population. To further understanding of food insecurity in specific mental health populations, we used data from the study of adults with mood disorders to answer the following research questions: (1) what is the prevalence of food insecurity compared to a general population sample?; and (2) is food insecurity associated with poorer nutrient intakes and psychological function? It was hypothesized that in this sample of adults with mood disorders, food insecurity would be: (1) significantly more prevalent than in the general population; (2) associated with suboptimal nutrient intakes based on defined standards; and (3) associated with poorer psychological functioning.

Methods

Sample

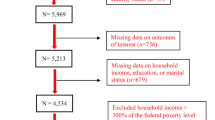

The data were from a cross-sectional nutrition survey of adults (>18 years) with clinically defined mood disorders (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders or SCID; [13]) who lived in the lower mainland of British Columbia; 146 individuals were randomly selected from the membership list of the Mood Disorder Association of British Columbia and invited to participate. Of the 146 randomly selected members, 26 were deemed ineligible and 23 refused to participate. Eleven of the 23 individuals who declined participation completed a non-response questionnaire, and statistical comparisons showed no significant differences compared to the respondents based on a variety of lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, multivitamin use).

As part of the recruitment process, all individuals received phone follow-up from research staff to determine their interest and eligibility. Full details of recruitment, data collection, quality control, and overall nutrient intake results have been published previously [12]. This study adhered to guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board. Sufficiency of statistical power (minimum 80%) to conduct the analysis was based on: (1) the hypothesis, food insecurity would be associated with lower nutrient intakes; (2) results from a Canadian study on food insecurity and nutrient intakes reporting mean intakes of folate of 424 and 378 micrograms for food-secure and food-insecure groups, respectively, with a common standard deviation of 18.5 [14]; and (3) an alpha level of 0.05 [15].

Measurements

Dependent variable

Food insecurity

Food insecurity status was determined as having an affirmative response to at least one of the two screening questions:

-

1.

In the past 12 months did you worry that there would not be enough to eat because of lack of money? (Question description: Worry about food access).

-

2.

In the past 12 months did you not have enough food to eat because of lack of money? (Question description: Compromised diet).

These two screening questions, which have previously been used in Statistics Canada national surveys [16], were also used in the British Columbia Nutrition Survey and allowed for direct comparisons of food insecurity between the sample and the general population. In the Canadian survey and in our study, a third question was also used: “In the past 12 months, did you or anyone in your household not have enough food to eat because of a lack of money?”. All of our study respondents who responded affirmatively to question two also indicated “yes” to the third question. Due to this redundancy in responses, the third question was not included in the analysis.

Independent variables

Psychological functioning and symptoms

Psychological, social, and occupational functioning was based on scores of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) [17]. Current symptoms of depression and mania were measured based on the Hamilton Depression Scale (Ham-D) [18], and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [19].

Diet

Nutrient intakes were derived from 3-day food records (two weekdays and one weekend day; non-consecutive) according to standard protocols [20]. The dietary variables included intakes of energy, macronutrients, and selected micronutrients (i.e., vitamins B6, B9, B12, and C, plus the trace minerals iron, and zinc) that function in cognition, and were analyzed using Food Processor SQL with the Canadian nutrient file [21].

Covariates

Covariates included in the analysis were body mass index (BMI; kg/m2; continuous variable) measured according to standard protocols used in national and provincial nutrition surveys [20], diagnosis of depressive or bipolar disorder based on the SCID (dichotomous), following a therapeutic (diet for a medical condition) diet (dichotomous), sociodemographic factors including age (continuous), gender (male/female), in a relationship or not (dichotomous), and income (dichotomized as low versus adequate, based on Canadian government standards).

Data analysis

To test the first hypothesis, prevalence estimates of food insecurity (i.e., affirmative response to at least one of the two food insecurity screening questions) and low income were compared (using binomial tests of two proportions) to regional data available from the 1999 British Columbia Nutrition Survey (BCNS; n = 1,823) that contained the same income and food insecurity measures [20]. The BCNS was conducted by the British Columbia Ministry of Health Services, Health Canada, and the University of British Columbia. It randomly sampled British Columbians aged from 19 to 84 years. Most of the BCNS participants were married (65.2%), did not hold a university degree (85.5%), and had income levels above the poverty cut-off (74.8%).

To examine the second hypothesis, differences in nutrient intakes between respondents who were either food-insecure or secure were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests or binomial tests of two proportions based on the Dietary Reference Intakes [22]. Specifically, the proportion of the sample above and below the Estimated Average Requirements (EAR; to estimate prevalence of possible nutrient inadequacy) or within and above the Adequate Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR; to estimate suboptimal or excess macronutrient intake) were analyzed.

To test the third hypothesis, bivariate relationships between food insecurity and the psychological measures were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and crude prevalence ratios. Cut-offs used to categorize the mental health measures included scores of 7 or less for the Ham-D [18] and 12 or less for the YMRS [19] which indicate that symptoms are currently absent. A cut-off of 60 for the GAF was used; scores less than this indicate more severe mental illness [23].

The final steps of the analysis involved conducting Poisson regression with robust variance to examine relationships between food insecurity and psychological functioning while adjusting for age, sex, relationship status, and income. This particular method was chosen as it is considered the most viable model option when analyzing cross-sectional data [24]. It provides adjusted prevalence ratios that are interpreted as the ratio of the proportion of the persons with the outcome (e.g., low GAF scores) over the proportion with the exposure (e.g., food insecurity). To test whether the Poisson model form fit the data, the goodness-of-fit Chi-squared test was applied. All data analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 [25].

Results

Description of sample

Similar to the general population sample studied in the BCNS, most respondents (n = 97) were females (n = 69; 71.1%). Unlike the BCNS, most did not have a university degree (n = 76; 78.4%) and were not in a relationship (61.9%). Approximately half of the sample (49.0%) had government defined low-income levels (Statistics Canada, 2013). Most (67.0%) had body mass indices greater than 24.9 kg/m2 and 19.0% indicated they were following a specific diet for medical reasons. Based on the SCID, 58 (59.8%) met criteria for bipolar disorder and 39 (40.2%) for depressive disorder. More than 85% of the participants were taking psychiatric medications.

Comparison of prevalence estimates of food insecurity

As hypothesized, the sample of adults with mood disorders had a higher proportion of individuals (36%) experiencing food insecurity (p < 0.001) compared to the general population sample (BCNS) (Table 1). The proportion of individuals reporting low-income status was also higher in adults with mood disorders (p < 0.05).

Food insecurity and nutrient intakes

The respondents who reported food insecurity had lower median carbohydrate and vitamin C intakes (Table 2). The assessment of nutrient intakes based on the EARs indicated that those reporting food insecurity had higher proportions of inadequate protein, folate and zinc intakes (p < 0.05). The food-insecure group also had a higher proportion of participants with excess total fat intakes as measured by the AMDR (p < 0.05).

Food insecurity and psychological functioning

Based on the bivariate analysis, some associations were found between food insecurity and psychological functioning when measured as continuous variables (Table 3). Ham-D and YMRS scores were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in participants with compromised diet (i.e., answered affirmatively to the food insecurity screening question “In the past 12 months did you not have enough food to eat because of lack of money”). In addition, higher depression scores were found in those reporting low income (p < 0.05).

Crude prevalence ratios (PRs) of food insecurity and the psychological measures (dichotomized based on their defined cut-off scores) showed significant association between food insecurity and mania symptoms (Table 4). When Poisson regression was applied, the ratio of the proportion of respondents with high YMRS scores over the proportion with food insecurity was 2.37 (95% CI 1.49–3.75, p < 0.001). Low income was also consistently associated with worse scores on all psychological measures (adjusted PRs ranged from 2.68 to 2.88, p < 0.05). The variables in the final three Poisson regression models included the psychological measures (i.e., GAF, YMRS, Ham-D, respectively) age, sex, and income. The goodness-of-fit Chi-squared test results were not significant for all models (goodness-of-fit 51.34 to 55.01, p’s > χ2 (92) = 1.00) suggesting that the Poisson model form fit the data.

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that food insecurity was more prevalent in adults with mood disorders when compared to a general population. Sample respondents who reported food insecurity had significantly lower intakes of carbohydrates and vitamin C. A higher proportion of the adults with mood disorders had potentially inadequate intakes of protein, folate, and zinc. Finally, food insecurity was consistently associated with worsened mania symptoms in adults with mood disorders.

This is the first study to report the relationships between food insecurity and selected nutrients in adults with mood disorders. As shown in other studies of food insecurity in different populations [14, 26–28], there is higher risk of inadequate intakes of essential nutrients which can have profound effects on mental health. Research conducted in this sample of adults with mood disorders has shown positive correlations between nutrient intakes and psychological function [29].

There are multiple interconnected ways in which food insecurity could contribute to poorer nutritional and psychological health, including through nutrient deficiencies and/or the body’s physiological response to the immense stress from not having the resources to feed oneself and/or one’s family [30–32]. When people experience food insecurity, they may be forced to consume food in socially unacceptable ways [33] which may affect psychological function directly or indirectly by altering nutrient intakes and metabolism. For example, reduced blood folate levels (that may be a result of compromised dietary folate intake due to food insecurity) may impair one-carbon metabolism, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psychiatric symptoms [34]. While previous studies have shown links between food insecurity and psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and suicide ideation [6, 7, 28, 35, 36], our results are the first to show association with mania symptoms. One mechanism underlying this relationship may be due to suboptimal blood levels of vitamin C caused by either lower intakes and/or increased breakdown due to stress. With lower blood levels of vitamin C, disequilibrium between ascorbic acid and vanadium metabolism may occur and result in mania symptoms [37].

The consistent association between low-income status and worse scores on the psychological measures is not surprising as other studies have shown links with depression and low income [38]. However, to our knowledge, this study is the first to report associations with YMRS and GAF scores. While food insecurity is an independent determinant of health [39], cross-sectional surveys have also shown it is strongly linked with another health determinant, inadequate income [16, 40–42]. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of these investigations and our study cannot determine the temporality of the relationships among food insecurity, low income, and mental health. However, longitudinal studies have shown that associations between food insecurity and depression are bidirectional [30, 43].

For several reasons, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Limitations include the modest sample size and that the food insecurity screening questions may not discriminate varying degrees of food access. However, previous studies indicate that short form measurement tools are appropriate to determine the subjective experiences of food insufficiency [44]. Measurement error between food insecurity and psychological functioning may be present as the two may be correlated (e.g., people in depressed mood states might report increased food insecurity regardless of their true status) and thereby yield a spuriously stronger positive association. However, the multivariate analysis did not show an association between food insecurity and Ham-D scores. Finally, most of the sample was taking psychiatric medications which may impact on food-related behaviours (e.g., increase appetite) [45] and therefore, increase food insecurity.

Conclusions

Food insecurity is an important determinant of health and significant public health and social issue [39, 40]. This study extends the current body of food insecurity knowledge by providing prevalence estimates and reported associations with poorer nutrient intakes and psychological functioning in a sample of adults with mood disorders. While program and policy developments that strengthen food security would reduce health and social inequities [41, 42], it may also be speculated that such interventions may enhance the nutritional and psychological well-being of those with mood disorders. Future investigations should focus on interventions aimed at improving food security to establish its role in enhancing mental health.

Abbreviations

- AMDR:

-

Adequate Macronutrient Distribution Ranges

- BCNS:

-

British Columbia Nutrition Survey

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- EAR:

-

Estimated Average Requirement

- Ham-D:

-

Hamilton Depression scale

- YMRS:

-

Young Mania Rating Scale

- GAF:

-

Global Assessment of Functioning scale

References

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2012) The state of food insecurity in the world: economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutrition. FAO, Rome. http://www.un.org/ru/publications/pdfs/state%20of%20the%20food%20insecurity%20in%20the%20world%202012%20fao.pdf

Anderson SA (1990) Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr 120(Suppl 11):1559–1600

Monsivais P, Drewnowski A (2007) The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Am Diet Assoc 107(12):2071–2076

Klesges LM, Pahor M, Shorr RI, Wan JY, Williamson JD, Guralnik JM (2001) Financial difficulty in acquiring food among elderly disabled women: results from the women’s health and aging study. Am J Public Health 91(1):68–75

Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS (2003) Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr 133(1):120–126

Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA (2002) Family food insufficiency, but not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia and suicide symptoms in adolescents. J Nutr 132(4):719–725

Wu Z, Schimmele C (2005) Food insufficiency and depression. Soc Perspect 48(4):481–504

Gunderson C, Kreider B (2009) Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J Health Econ 28(5):971–983

Sorsdahl K, Slopen N, Siefert K, Seedat S, Stein DJ, Williams DR (2011) Household food insufficiency and mental health in South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health 65(5):426–431

Muldoon KA, Duff PK, Fielden S, Anema A (2013) Food insufficiency is associated with psychiatric morbidity in a nationally representative study of mental illness among food insecure Canadians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(5):795–803

Gsisaru N, Kaufman R, Mirsky J, Witztum E (2011) Food insecurity and mental health: a pilot study of patients in a psychiatric emergency unit in Israel. Community Ment Health J 47(5):513–519

Davison KM, Kaplan BJ (2011) Vitamin and mineral intakes in adults with mood disorders: comparisons to nutrition standards and associations with sociodemographic and clinical variables. J Am Coll Nutr 30(6):547–558

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2001) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition. (SCID-I/NP). Biometrics Research, New York

Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V (2008) Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr 138(3):604–612

Rosner B (2010) Fundamentals of biostatistics, 7th edn. Duxbury Press, Pacific Grove

Che J, Chen J (2001) Food insecurity in Canadian households [1998/99 data]. Health Rep 12(4):11–22

Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J (1976) The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33(6):766–771

Hamilton M (1960) A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 23:56–62

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA (1978) A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133:429–435

BC Ministry of Health Services (2004) British Columbia Nutrition Survey—Report on Energy and Nutrient Intakes. BC Ministry of Health Services, Victoria

Canada Health (2010) Canadian nutrient file. Health Canada, Ottawa

Institute of Medicine (2000) Dietary reference intakes: applications in dietary assessment. National Academies Press, Washington

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E et al (2003) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(2):184–189

Lee J, Tan CS, Chia KS (2009) A practical guide for multivariate analysis of dichotomous outcomes. Ann Acad Med Singapore 38(8):714–719

StataCorp (2007) Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. StataCorp LP, College Station

McIntyre L, Glanville NT, Raine KD, Dayle JB, Anderson B, Battaglia N (2003) Do low-income lone mothers compromise their nutrition to feed their children? CMAJ 168(3):686–691

Tarasuk V, McIntyre L, Li J (2007) Low-income women’s dietary intakes are sensitive to the depletion of household resources in one month. J Nutr 137(8):1980–1987

Lee J, Frongillo EA Jr (2001) Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons. J Nutr 131(5):1503–1509

Davison KM, Kaplan BJ (2012) Nutrient intakes are correlated with overall psychiatric functioning in adults with mood disorders. Can J Psychiatry 57(2):85–92

Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR (2005) Food insufficiency and women’s mental health: findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Soc Sci Med 61(9):1971–1982

Huddleston-Casas C, Charigo R, Simmons LA (2009) Food insecurity and maternal depression in rural, low-income families: a longitudinal investigation. Public Health Nutr 12(8):1133–1140. doi:10.1017/S1368980008003650.226

Davison KM, Nig E, Chandrasekera U, Seely C, Cairns J, Mailhot-Hall L et al (2012) Promoting mental health through healthy eating and nutritional care. Dietitians of Canada, Toronto. http://www.dietitians.ca/mentalhealth

Piaseu N, Belza B, Shell-Duncan B (2004) Less money less food: voices from women in urban poor families in Thailand. Health Care Women Int 25(7):604–619

Kronenberg G, Colla M, Endres M (2009) Folic acid, neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disease. Curr Mol Med 9(3):315–323

Davison KM, Marshall-Fabien GL, Tecson A (2015) Association of moderate and severe food insecurity with suicidal ideation in adults: national survey data from three Canadian provinces. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50(6):963–972. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1018-1

Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC et al (2011) Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr 94(6):1729S–1739S

Naylor GJ, Corrigan FM, Smith AH, Connelly P, Ward NI (1987) Further studies of vanadium in depressive psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 150:656–661

Topuzoğlu A, Binbay T, Ulaş H, Elbi H, Aksu Tanık F, Zağlı N et al (2015) The epidemiology of major depressive disorder and subthreshold depression in Izmir, Turkey: prevalence, socioeconomic differences, impairment and help-seeking. J Affect Disord 181:78–86. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.017

McIntyre L, Rondeau K (2009) Food insecurity. In: Raphael D (ed) Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. Canadian Scholar’s Press Inc, Toronto, Ontario

Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N (2013) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2012. Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF): 2014. Toronto, Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.nutritionalsciences.lamp.utoronto.ca

Office of Nutrition Policy & Promotion, Health Canada (2007) Canadian community health survey, cycle 2.2, nutrition (2004): income-related household food security in Canada. Health Canada, Ottawa

McIntyre L, Connor SK, Warren J (2000) Child hunger in Canada: results of the 1994 National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. CMAJ 163(8):961–965

Huddleston-Casas C, Charigo R, Simmons LA (2008) Food insecurity and maternal depression in rural, low-income families: a longitudinal investigation. Public Health Nutr 12(8):1133–1140. doi:10.1017/S1368980008003650

Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S (2008) Household food insecurity in the United States. USDA Economic Research Service, Washington, DC

Davison KM (2013) The relationships among psychiatric medications, eating behaviors, and weight. Eat Behav 14(2):187–191

Authors’ contributions

KMD conducted the study as part of her doctoral studies and was supervised by BJK. KMD drafted the manuscript and BJK helped with revisions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank their funding source, The Danone Research Institute. The second author also thanks the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute for ongoing support. We also acknowledge the assistance of the Mood Disorders Association of British Columbia for providing support staff, office space and assistance with recruitment.

Funding

Financial support for this project was obtained from The Danone Research Institute, which played no role in carrying out the study, analyzing the results, or influencing publication.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Karen M Davison and Bonnie J Kaplan have contributed equally to this work

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Davison, K.M., Kaplan, B.J. Food insecurity in adults with mood disorders: prevalence estimates and associations with nutritional and psychological health. Ann Gen Psychiatry 14, 21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-015-0059-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-015-0059-x