Abstract

Background

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a hyperinflammatory condition with uncontrolled activation of lymphocytes and macrophages. Besides a primary (genetic) form, HLH can also be triggered by malignant, autoimmune and infectious diseases. HLH recurrences are rarely described, usually only in primary HLH. Parvovirus B19 (PVB19) Infection is one of the rare and rather benign causes of HLH. Since the infection usually results in long-lasting immunity, recurrent viremia is very uncommon.

Case presentation

We report an unusual case of a young female with recurrent PVB19 infection that led to repeated episodes of HLH. The first episode occurred at the age of 25 years with a three-week history of high fever and nonspecific accompanying symptoms. The diagnosis of HLH was confirmed by HLH-2004 criteria and HScore, PVB19 viremia was detected as underlying cause. Following guideline-based therapy, the patient was symptom-free for one year, before similar symptoms recurred in a milder form. Again, PVB19 was detected and HLH was diagnosed according to HScore. After successful treatment and a nine-month symptom-free interval, a third phase of hyperinflammation with low PVB19 viremia occurred; this time, treatment with a corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulin was initiated before the presence of clear diagnostic criteria for HLH. No further events occurred in the following three years.

Conclusions

In the case of our patient, the recurrent viremia triggered three episodes of hyperinflammation, two of which were clearly diagnosed as HLH. To our knowledge, this is the first published case of recurrent HLH due to PVB19 infection. Therefore, the case gives new insights in triggering mechanisms for HLH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since its first description in 1939 [1], hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) has been subclassified into various entities including primary (genetic) and various secondary forms. Common to all entities is a hyperinflammatory state with uncontrolled activation of lymphocytes and macrophages, often—but not necessarily—resulting in manifest hemophagocytosis and critical illness [2]. Diagnostic criteria for the primary form have last been updated in 2007. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is confirmed if at least five out of eight diagnostic criteria are met. These criteria comprise cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, hyperferritinemia, elevated soluble CD25 (each above defined levels), and fever, splenomegaly, hemophagocytosis, and impaired NK cell activity [3]. The HLH-2004 criteria were generally used for secondary HLH (sHLH) as well; only in 2014, with the HScore, diagnostic criteria for secondary forms of HLH have been introduced. HScore is calculated as a sum of nine variables corresponding to different clinical and laboratory characteristics including immunosuppression, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, AST elevation and hemophagocytosis. The sum values are associated with different probabilities of a correct diagnosis of HLH, the optimal cut-off is 169 [4].

Infection associated sHLH has first been described in 1979 as a hyperinflammatory condition following viral infections [5]. Since then, different pathogens have been described as triggers for sHLH, including viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa. The most frequent causative agent, however, appears to be Epstein-Barr-Virus [6]. Parvovirus B-19 (PVB19) has rarely been identified as causative agent for sHLH, with a usually rather benign course of disease. Several cases of PVB19-induced sHLH were associated with hematologic disorders [7].

Infection with PVB19 usually results in sustained immunity against the virus. Persisting infection and recurrences have rarely been reported in immunocompetent individuals [8, 9]. In the following, we describe the case of an otherwise healthy female, who suffered repeated episodes of HLH during episodes of PVB19 viremia within a period of two years.

Case presentation

Our patient’s first episode of sHLH occurred at the age of 25 years. She was admitted to hospital because of high fever, cough, joint pain, and dizziness that had been present for three weeks. She did not report any pre-existing conditions or a family history of autoimmune diseases. Physical examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic work-up revealed an active PVB19 infection with a positive PCR with 1,761 IU/ml and high level of IgG (Index > 46, reference < 0.9) but no detection of IgM antibodies (LIAISON® Biotrin Parvovirus B19 IgG; IgM). Further diagnostic testing revealed no evidence of underlying immunodeficiency or concomitant malignant, infectious or autoimmune disease (including CT scan of neck, chest and abdomen, abdominal and cardiac ultrasound, interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis, serologies for HIV, CMV, EBV, viral hepatitis A, B, C, E, Treponema, Bartonella, Brucella, Coxiella, Legionella, Leptospira, Leishmania, and Toxoplasma, as well as ANA, ENA, ANCA, anti-LKM-1, AMA-M2, ASMA, anti-CCP and rheumatoid factors).

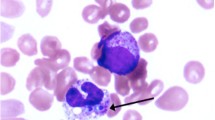

Tricytopenia, pronounced elevation of ferritin, splenomegaly, and elevation of soluble CD25 confirmed the suspected diagnosis of sHLH. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, but the material obtained was of low quality and therefore diagnostically inconclusive with regard to possible hemophagocytosis or detection of PVB19-DNA. Under therapy with corticosteroids, etoposide (four doses of initially 50 to finally 100 mg/m2) and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) according to the current treatment guideline [10], disease remission of HLH and control of PVB19 infection were achieved. One year later, similar symptoms recurred. With evidence of PVB19 viremia (275 IU/ml) and elevation of ferritin and tricytopenia, the clinical diagnosis of sHLH relapse and recurrent replication of PVB19 was made and successfully treated with corticosteroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG). A third episode of HLH occurred another nine months later with detection of a low amount of PVB19-DNA (2 IU/ml) and elevated inflammatory biomarkers. Although the diagnostic criteria for HLH were not fully met, we considered the comparatively mild symptoms to be incipient sHLH and started treatment with IVIG and prednisolone, which resulted in rapid resolution of symptoms. The patient has since been healthy without relapses for three years. Table 1 gives details of clinical and diagnostic characteristics of the three episodes.

After the third episode, we performed an additional immunologic workup: Immunophenotyping with fluorescence-based flow cytometry showed T-lymphopenia with only 219 CD4+ cells/µl despite repeated negativity for HIV. CD4+ and CD8+ cells showed normal HLA-DR expression. Additionally, few class-switched memory B-cells (IgD−/CD27+) were detected (3/µl), but total immunoglobulins including IgG-subclasses were within normal range. Absolute number of NK cells (CD56+/CD3−) was within normal range, NK cells showed normal perforin expression (intracellular staining with perforin antibody) and normal degranulation activity (CD107a) following stimulation with target cells compared to healthy controls. Genetic analysis of possible underlying causes of HLH was recommended to the patient following discharge, but ultimately not conducted.

Conclusions

Reactivation or persistence of PVB19 viremia is an uncommon event in immunocompetent individuals. Interestingly, at the time of diagnosis of the first episode of HLH in our patient, high PVB19-specific IgG levels but no IgM were detected, suggesting that this episode was in fact already a reactivation of persistent PVB19 infection rather than a primary infection. In previous reports, the possibility of persistent infection of the bone marrow with PVB19 is discussed [7], unfortunately in our case, bone marrow biopsy did not yield adequate material for PCR. The PCR results from blood during the different hospital admissions show decreasing viral load over the three episodes, probably due to improved specific immunity by a CD4+ cell-mediated booster effect as known from other viral infections [11]. However, this could not be quantified, because repeatedly high concentrations of PVB19-specific IgG were measured (i.e.: index > 46) throughout the two-year course. The decreasing viremia went along with ameliorated HLH symptoms from first to third episode. Previous reports suggest that PVB19 induces rather benign courses of sHLH, which in some cases do not even require specific HLH therapy [6]. In other infectious triggers like malaria, spontaneous resolution of HLH symptoms has been shown with clearance of the infectious agent [12].

During the first episode, both HLH-2004 criteria and HScore unambiguously supported the diagnosis of sHLH. During the second episode, only three HLH-2004 criteria were met, while an HScore of 193 (corresponding to a calculated likelihood of 80–88%) conclusively indicated HLH. The detected PVB19 viremia was lower this time and symptoms were overall milder. We assume that this is due to the earlier diagnosis, since the treating physicians and the patient were aware of her medical history. Because of the less severe symptoms, no etoposide was administered. The diagnosis of a third episode of sHLH is ultimately elusive, as neither the HLH-2004 criteria nor the HScore provide clear evidence of HLH. Nevertheless, inflammatory biomarkers were elevated and PVB19 detectable. Considering the patient's medical history, we therefore made a diagnosis of incipient sHLH and initiated early treatment with prednisolone and IVIG, which quickly led to resolution of symptoms.

Regarding the diagnostic criteria, it should be mentioned that bone marrow aspiration during the first episode was not diagnostically meaningful due to low quality of the aspirate. Since the diagnosis was already confirmed, we decided against repeated bone marrow biopsy and against bone marrow puncture during the relapses. The absence of this value may have reduced diagnostic accuracy of HScore and HLH-2004 criteria during the second and third episode. Since bone marrow is a potential reservoir for PVB19, a bone marrow analysis for PVB19-DNA would also be helpful in assessing the course of infection and should therefore be sought in case of further relapse.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is usually considered a threshold disease, which—once a tipping point is exceeded—leads to uncontrolled, self-sustained hyperinflammation and macrophage activation [2]. Relapse of HLH has been described, but it is usually associated with primary HLH, which is caused by genetic disorders of CD8+ T cells and NK cells [13]. Although immune cell phenotyping in our case yielded no evidence of primary HLH, a genetic overlap between primary and secondary HLH is discussed [2]. Our patient’s case therefore provides new insights into possible long time prognosis of sHLH and suggests that the recurrence of triggering effects—in this case PVB19 viremia—is capable of inducing relapse of sHLH.

Availability of data and materials

All clinically relevant data have been made available within the manuscript. For data protection reasons, no further clinical data can be made available.

Abbreviations

- HLH:

-

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- PVB19:

-

Parvovirus B19

- sHLH:

-

Secondary HLH

- IVIG:

-

Intravenous immune globulin

References

Scott RB, Robb-Smith AHT. Histiocytic medullary reticulosis. Lancet. 1939;234(6047):5.

Brisse E, Wouters CH, Matthys P. Advances in the pathogenesis of primary and secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: differences and similarities. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(2):203–17.

Henter JI, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–31.

Fardet L, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613–20.

Risdall RJ, et al. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a benign histiocytic proliferation distinct from malignant histiocytosis. Cancer. 1979;44(3):993–1002.

Rouphael NG, et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(12):814–22.

Kalmuk J, et al. Parvovirus B19-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(11):2076–81.

Sasaki T, et al. Persistent infection of human parvovirus B19 in a normal subject. Lancet. 1995;346(8978):851.

Mogensen TH, et al. Chronic hepatitis caused by persistent parvovirus B19 infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:246.

La Rosée, P.B. et al.: Onkopedia Leitline Hämophagozytische Lymphohistiozytose (HLH) 2020, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie e.V. https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/haemophagozytische-lymphohistiozytose-hlh/@@guideline/html/index.html. Accessed 17 Dec 2021

Lim EY, Jackson SE, Wills MR. The CD4+ T cell response to human cytomegalovirus in healthy and immunocompromised people. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:202.

Muthu V, et al. Malaria-associated secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Report of two cases & a review of literature. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145(3):399–404.

Yildiz H, et al. Clinical management of relapsed/refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adult patients: a review of current strategies and emerging therapies. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:293–304.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HMO, AF and NL collected the clinical data. HMO wrote the first version of the manuscript, all authors contributed significantly to the final version. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Publication of this case report is in accordance with the regulations of the Ethical Board of the Heinrich-Heine University Düsseldorf.

Consent for publication

The participant has given written informed consent to the submission of the case report to the journal.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Orth, H.M., Fuchs, A., Lübke, N. et al. Recurrent parvovirus B19 viremia resulting in two episodes of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Virol J 19, 107 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01841-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01841-y