Abstract

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a pressing global health concern that threatens the efficacy of antibiotics and compromises the treatment of infectious diseases. The private health sector, including private hospitals, private clinics, private doctors, and private drug stores, play crucial roles in accessing antibiotics at the primary health care level, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), however, it also brings high risks of AMR to communities, for example, non-prescriptive antibiotic sales. In Vietnam, AMR is highly prevalent due to the inappropriate use or overuse of antibiotics in clinical settings and in the community. This study aimed to assess the regulatory framework governing antibiotic resistance in Vietnam’s private health sector by examining international and national successful strategies and approaches to control AMR in the private health sector.

Methods

The literature search was used to gather international experiences and official Vietnamese documents related to AMR control in the private health sector. Web of Science, PubMed, and Cochrane were utilized as the main sources for academic database, meanwhile, Google Search Engine was used as the additional source for grey literature and international guidelines and reports. The methodological framework of the scoping review was based on Arksey and O'Malley’s guidelines. The selection criteria were articles and documents pertinent to AMR control, antibiotic use and dispensing regulations in the private health sector.

Results

Analysis from 118 documents (79 of them on international experience) revealed various successful strategies employed by countries worldwide to combat AMR in the private health sector, including the establishment of surveillance networks, antibiotic stewardship programs, interagency task forces, public‒private partnerships, and educational initiatives. Challenges in AMR control policies in Vietnam’s private health sector existed in AMR surveillance, intersectoral coordination, public‒private cooperation, resource allocation, and regulatory enforcement on the sale of antibiotics without prescriptions.

Conclusion

The findings highlight the role of surveillance, medical education, regulatory enforcement in antibiotic prescription and sales, and public‒private partnerships in promoting rational antibiotic use and reducing the burden of AMR in the private health sector. Addressing AMR in Vietnam’s private health services requires a multifaceted approach that includes regulatory enforcement, surveillance, and educational initiatives for private health providers and communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global challenge that threatens the ability to treat common infectious diseases with antibiotics. Antimicrobial resistance directly causes more than 1.27 million deaths worldwide each year and represents a significant economic burden on health systems [1,2,3,4]. Within 30 years, AMR is predicted to be one of the leading causes of death globally, disproportionately affecting populations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [5].

The private health sector, including private hospitals, private clinics, private doctors and private drug stores, offer convenient access to antibiotics for individuals seeking primary healthcare services. This is particularly important in LMICs, where urbanization is increasing and public healthcare facilities may be limited, especially in rural communities [6, 7]. The high demand for antibiotics in the private sector, combined with a lack of regulatory controls over antibiotic dispensing at local levels, has led to increased consumption and overprescription of antibiotics, exacerbating the spread of AMR [7, 8]. According to a systematic review of 52 countries, the non-prescriptive antibiotic distribution in community settings was 63.4% [9]. In AMR prevention and control, these entities are instrumental in promoting responsible antibiotic use practices through patient education, prescription monitoring, and adherence to treatment guidelines [10].

AMR is highly prevalent in Vietnam, especially in urban areas where health services are easily accessible. Due to economic incentives for drug sellers to satisfy consumer demands and lack of knowledge on AMR from both drug sellers and consumers, many private clinics and pharmacies dispense antibiotics without prescriptions, leading to overuse and misuse of antibiotics [11]. This inappropriate use of antibiotics in communities contributed largely to the increasing incidence of drug-resistant infections in Vietnam [12, 13]. A national survey of 360 private drugstores in nine Vietnamese provinces in 2017 showed more than 80% of antibiotic purchases were without prescriptions and mainly for respiratory infections [14]. According to a report from Ministry of Health (MOH) of Vietnam, approximately one-third of antibiotics used each year in Vietnamese hospitals were considered unnecessary [15], and this rate was likely to be even higher at the primary health care levels, especially among private pharmacies and informal sellers serving local markets [15].

The Vietnamese government has recognized AMR as one of national health security priorities [16]; however, to date, regulations aimed at addressing the inappropriate use and supply of antibiotics have had limited impacts, particularly with private pharmacies. Besides, the current interventions to reduce AMR have focused on hospital-level stewardship programs, and was lack of attention to the large quantities of antibiotics consumed at the community level [17]. Under the increased pressure on the public health system and economic loss for business owners, the enforcement of the regulations to control antibiotic use and AMR in the private health sector is limited in practice [7, 13, 17] and restrictive provisions are imposed to address their consequences [18]. A recent study identified health system challenges in AMR interventions, such as limited cooperation between national management bodies and shortages of human resources at all levels [19]. However, the gaps and challenges in controlling antibiotic use and AMR in the private health sector were not clearly addressed.

This study aimed to identify successful approaches and interventions from countries and organizations around the world and reflect them with AMR control policies in Vietnam. The findings from the study could provide evidence and recommendations for strengthening the legal framework governing the prescription, distribution and use of antibiotics to control AMR in the private healthcare sector in Vietnam and similar countries.

2 Methods

A perspective literature search was conducted to collect international experiences; interventions; strategies; official Vietnamese documents (national action plans, legal documents, etc.); scientific documents; reports (evaluation and analysis reports) related to AMR control and rational use of antibiotics in the private health sector. To ensure a reliable and reflective examination of the literature, Arksey and O'Malley’s methodological framework [20] was used as outlined below to ensure the rigor, transparency, validation, and replication of the current findings. This method proved effective in identifying key practices and providing evidence to suggest necessary changes to previous literature [19, 21].

2.1 Research questions

Three major questions were considered for this study, aligning with the main objectives: (i) What the strategies, approaches, and interventions have been successfully implemented to control AMR in the private health sector accross different countries? (ii) What are Vietnam’s legal provisions related to AMR in the private health sector? (iii) What are the key factors affecting AMR control in the private health sector worldwide and in Vietnam?

2.2 Identify relevant documents

2.2.1 Search strategy

Electronic database searches were performed with the Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane as the main sources for academic papers [22,23,24], and the Google Search Engine as an additional source for grey literature, governmental policies and institutional reports [25,26,27]. A Boolean algorithm was used to search for variations in spelling, and the global terminology was adjusted using the following keywords: AMR/antibiotic resistance/antimicrobial resistance/antibiotic use/antibiotic prescription/Antibiotic Stewardship Program, control/ regulation/law/enforcement/policy, and private/private sector. Lists of references and relevant articles for identified articles were also searched manually. The keywords and syntax for searching was described in the Supplementary Material.

2.2.2 Selection criteria

Various definitions and concepts of the private health sector were considered. For example, WHO defined the private health sector as “individuals and organizations that are not directly owned or controlled by the government and are involved in the provision of health services” [28]. By this definition, the private health sector can be classified into for-profit and nonprofit, formal and informal, and domestic and international groups. According to a 2017 study on the role of the private sector in health coverage in Vietnam [29], the private health sector included “private hospitals, private clinics, traditional medicine diagnostic rooms, units providing paraclinical services and other medical services”. In another article titled “Antibiotic resistance and the private sector in Southeast Asia”, Marco Liverani mentioned the private healthcare sector, which consisted of “large private hospitals, clinics and small pharmacies to informal drug sellers, drug vendors and traditional healers” [30].

In the context of this study, we defined the private health sector as anyone of four groups: private hospitals, private clinics, private pharmacies/drug stores, and private doctors. These individuals/units are directly involved in prescribing or providing antibiotics to people. These subjects are also regulated by the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment issued in 2009 [31], the revised Law on Medical Examination and Treatment in 2023 [32], and by the Law on Pharmaceuticals in 2016 [33]. Only articles in English and Vietnamese documents published from Japanuary 1, 2010 to December 31, 2023 were included. For empirical research, scientific validity assessments or statistical calculations are not used to draw conclusions.

2.2.3 Exclusion criteria

Documents specific to animals or those that did not respond to the research questions were excluded because the focus of this review was on regulations of AMR control and appropriate use of antibiotics in human. Other actors in private sector, such as pharmaceutical companies, traditional medicine clinics, traditional healers and drug sellers (in person or online), were not included in the study.

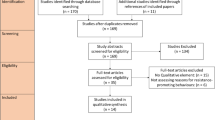

2.3 Study selection

Based on our search strategy, we found 595 articles from three sources including Web of Science (285), PubMed (273) and Cochrane (37). After removing duplicated publications, all the rest articles (523) were screened for its titles and abstracts. As a result, 166 articles were identified for full text assessment. In this step, we checked the eligbility of documents and an additional 118 articles were excluded, leaving 48 articles for review.

For the AMR prevention guidelines and strategies from international organizations and countries, we found 31 documents from the WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States of Ameria (USA), Canada, Australia, the European Union, the United Kingdom (UK), Denmark, Japan, and Korea, via Google Search Engine.

Regarding drug resistance control and prevention policies in Vietnam, we found 39 relevant documents in Vietnamese and English languages for reviewing and analysis (Tables 1 and 2). In total, 118 documents were finally recruited for this scoping review. The study was conducted from November 2023 to February 2024.

2.4 Charting the data

All the articles were compiled and put into analysis matrix tables according to the following contents: author, year of publication, country, data source, research objects, study design, and main findings (covers topics of interest such as AMR regulations, community engagement, the role of the private health sector, policy impacts, positive factors, and barriers).

2.5 Collating, summarizing and reporting results

After reviewing each document, the authors discussed the main findings and categorized them into the nine themes stated in the analytical framework. The global AMR strategies and good examples from other countries were served to provide a comprehensive benchmark for assessing Vietnam’s current approaches. Besides, these international examples could also offer practical, evidence-based solutions to enhance the control of AMR in Vietnam’s private healthcare sector.

3 Analysis framework

The analytical framework is based on the WHO Guidelines for AMR Action Plan Development and a review of the 2020–2021 global response to antibiotic resistance in 114 countries [142]. The former one offers 13 strategic interventions for countries when developing, implementing and monitoring national action plans to control AMR [143]. These interventions address the needs and barriers that people and patients face when accessing health services through a person-centered approach to AMR (Fig. 1). This approach is based on two foundations (Investigation—Research and Administration—Education—Awareness) and four pillars (Prevention; Access to essential services; Fast and accurate diagnosis; and Appropriate treatment management, quality). In this paper, the arrangement of strategies, plans, and good practices of subjects in private health sector were also based on these foundations.

Measures to reduce the incidence of AMR and reduce the incidence of death and AMR infection, as proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [143]

Research and analysis of National Action Plans of 114 countries evaluate the strength of strategies to manage and respond to antibiotic resistance at the global, national, regional and international levels [142]. This study is based on Anderson and colleagues’ analytical framework, which includes 53 indicators related to 18 areas divided into three phases: policy design, implementation tools, and monitoring and evaluation. Among the groups of implementation tools, this study classifies seven tool groups, namely, Investigation—Surveillance, Management Leadership on Antimicrobial Resistance, Infection Prevention and Control, Education, Community Awareness, Policy on Drug Resistance Use of Drugs, and Research and Development of New Antibiotics.

Based on the WHO’s strategies and analytical models for research on 114 countries, the research team proposed a framework to analyze the strategies, policies, and approaches of countries as well as Vietnam, focusing on group policies and implementation levels, as described in Table 1. The list of documents included in the analysis is provided in Table 2.

4 Results

4.1 Successful strategies and approaches for preventing and controlling AMR in the private healthcare sector

The summary of good practices from international and national strategies and guidelines were presented in Table 3. First, global efforts to combat AMR have highlighted the role of national and regional AMR monitoring networks. The global standardization of AMR surveillance was led by the WHO with the Global Antimicrobial Use and Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) in 2015 [81]. By 2021, GLASS had 111 participating countries [144]. High-income countries such as France established regional networks for AMR surveillance before GLASS, while LMICs lacked such systems.

The national surveillance network on AMR was successfully implemented in France with the active role and high effectiveness of private hospitals. The Regional Coordination Center for Hospital Infection Control (RAISIN) established a surveillance system with a focus on healthcare-associated infection (HAI) prevention and antibiotic stewardship programs in both public and private hospitals. This system was integrated into the European surveillance of HAI and controlled by the European Centre for Disease Control [145]. Under the RAISIN, the HAI in acute care settings in France decreased 38% between 2001 and 2006 for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [145]. The use of flouroquinolone in private acute care hospitals, which leads to comprehensive antibiotic resistance programs, decreased by 10% from 2006 to 2009 [82].

Specialized task forces to address AMR prevention were established to ensure that the participants from different sectors were private healthcare providers [146]. The US National Action Plan to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB) coordinated efforts across 17 agencies to combat antibiotic resistance, emphasizing policies for sustainable investment and access to new interventions [83]. Similarly, India initiated policy interventions and established a National Task Force on AMR Prevention, integrating AMR prevention into national programs [76]. They established a Statewide Task Force along with a Core Committee at the State level with the aim of improving basic antibiotic prescribing practices [76].

Public‒private partnerships play a crucial role in AMR prevention and control at the global and national levels in many countries. The Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance initiated by the United Nations works as an advocate for policies and actions to address AMR [84, 85]. The Call to Action on Antimicrobial Resistance—2021, signed by 113 member states and supported by 35 non-state actors, urges stakeholders to take concrete steps in combating AMR through promoting innovation and access and enhancing governance and accountability [86]. The US National Action Plan emphasizes private sector involvement through collaborations such as CARB-X to facilitate public‒private collaboration to accelerate the discovery of new treatments for AMR [88]. In India, partnerships involving 18 medical associations developed Antibiotic Prescribing Guidelines and promoted rational antibiotic use. This collaboration spans the human, animal, and environmental sectors; engages civil society; and was a task force that focused on state funding for rational antibiotic use and active participation in research on AMR [76].

One Health Policy Approach is widely adopted to address AMR, emphasizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. Countries such as the USA, the EU, Australia, Denmark, and Singapore are implementing One Health strategies through surveillance, research, education, and regulation of antibiotic use in various sectors [90,91,92]. The AMR challenge initiated by the US aimed to accelerate the fight against antibiotic resistance and promote a One Health approach globally [93]. EU policy involves Commission and Member States on strengthening AMR combat through a One Health approach [89]. Their guidelines on antibiotic use targeted the promotion of prudent antibiotic use with specific recommendations for various healthcare facilities, including the private sector [94, 95]. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has published a study on Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Health Care, which outlines a One Health approach to reducing AMR [99]. Similar approaches were also found in Denmark [100] and Singapore [101].

At primary health care level, Point-of-care testing (POCT) in private pharmacies and drug retail settings in LMICs can improve treatment-seeking behavior, reduce inappropriate antimicrobial use and resistance, and ease the burden on public healthcare services [48]. This intervention was particularly effective for early diagnosis and treatment at community level for malaria, pneumonia and respiratory tract infection. A narrative review highlighted that POCT is feasible and welcomed by both shops and customers when supported by community sensitization, training, reasonable pricing, infrastructure support, and healthcare integration. A study from Nigeria demonstrated that access to C-reactive protein (CRP) test kits and staff training in private community pharmacies significantly reduced the non-prescription dispensing of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections, with a reduction of 15.66% to 16% [42].

Interventions at hospitals and medical facilities focus on optimizing antibiotic use and infection control. The USA and Japan have implemented strategies to reduce antibiotic use in healthcare settings, including reimbursement incentives and infection control standards. The CDC provides resources such as the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs and offers educational materials to promote appropriate antibiotic use and infection prevention [103]. Besides, the Antimicobial Stewardship (AMS) program was also highly recommended by WHO and was applied successfully in hospital settings of many countries like India and France [37, 46]. Some other countries provided financial incentives to encourage AMR control in hospital, for example, in Japan. Both public and private hospitals in Japan could receive payments for infection control to reduce antibiotic use even in small ones (which had fewer than 200 beds). Starting in 2010, hospitals meeting infection control standards could receive reimbursement of 1000 yen (approximately 9 to 10 USD) per patient per admission. This was also a significant economic motivation to hire an infection control specialist with full-time certification [147]. By 2021, among Japan’s 8,300 hospitals, 69.5% were small hospitals. Health insurance reimburses 4000 yen per patient per admission for infection control measures in large hospitals and 1000 yen for small hospitals. This measure has significantly decreased drug-resistant bacteria rates in both types of hospitals [104].

Educational initiatives target private healthcare professionals and pharmacies to promote appropriate antibiotic use. Countries such as Canada, India, and South Africa emphasize guidelines, awareness campaigns, and regulatory frameworks to combat overprescription and ensure rational antibiotic use. In Canada, key areas for intersectoral cooperation include promoting appropriate antibiotic use in human and veterinary medicine and collaborating with the livestock industry to regulate veterinary drugs and promote alternatives to antibiotics [105]. In India, collaboration with medical associations has led to Clinical Guidelines on Prescribing Antibiotics, curriculum revisions in medical schools, and the implementation of Good Antibiotic Prescribing Practices (GAPP) across healthcare facilities [106]. In South Africa, a strict legal framework [67] ensures that only trained providers can prescribe or dispense medications.

Health communication and community awareness campaigns are essential for raising public awareness and engaging stakeholders in the fight against AMR. Governments in the USA and the UK collaborate with civil society organizations to educate the public and policymakers about AMR and implement national and local strategies to address this issue. This strategy has succeeded in increasing public awareness, reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, and improving surveillance capacity. However, ensuring consistent implementation at local levels remains a challenge [107]. A systematic review of 13 studies in LMICs found that educational interventions alone were insufficient to curb inappropriate antibiotic use in outpatient settings. However, multi-faceted interventions combining education with audit and feedback, rapid diagnostic tests, or peer-to-peer comparison are more effective. For example, in Hanoi, Vietnam, such interventions reduced antibiotic dispensing from 45 to 30% in pharmacies [39].

Efforts to reduce unnecessary and unreasonable prescribing involve policy interventions, regulatory frameworks, and awareness campaigns in countries in Latin America (particularly in Brazil), India and South Africa. In Brazil, a policy restricting over-the-counter (OTC) antimicrobial sales was implemented in November 2010 by the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA), requiring a medical prescription for such purchases. Studies have shown that this policy led to a significant reduction in antimicrobial sales, particularly amoxicillin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole [36, 49]. The impact was more pronounced in urban areas with better socioeconomic conditions and access to healthcare. In India, the government amended drug regulations in 2011 and engaged medical associations through the Chennai Declaration in 2012 to reduce the health costs associated with drugs. Schedule H1 was introduced in 2013 to better manage antibiotic usage [70]. Other methods for controlling AMR include improving vaccination rates and leveraging technology for better antibiotic prescribing practices [108,109,110].

4.2 Current regulatory documents in Vietnam on antibiotic control and antimicrobial resistance in the private health sector

The current regulatory documents in Vietnam regarding antibiotic control and antimicrobial resistance in the private health sector focus on six major challenges: surveillance, the AMR task force, the One Health approach, medical education, health communication and antibiotic sales.

First, while Vietnam established a national surveillance system for antibiotic resistance (VNASS) in 2016 involving 16 hospitals nationwide, private medical facilities are notably absent from this network [133]. Despite guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health in 2019 for implementing national surveillance of antibiotic resistance, private sector involvement remains limited [148]. In 2023, in the latest National Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistance Prevention for the period 2023–2030, with a vision to 2045, the role of the private sector was not mentioned clearly [128]. In many previous reports, the private sector (healthcare facilities and antibiotic business sector) lacked antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use surveillance strategies in humans [149].

In recent initiatives, Vietnam has made progress toward enhancing surveillance efforts [150]. According to the national strategy for treating AMR in 2023, Vietnam has committed to annually publishing a National Monitoring Study on AMR from 2023 and joining international systems such as the Global Health Safety Scale (GLASS) and the Western Pacific Regional Antibiotic Consumption Survey (WPRACSS) by 2027 [128]. The third goal of the strategy was to reduce the spread of viruses and infectious diseases with the goals of (i) improving the proportion of hospitals implementing proactive surveillance of HAIs and implementing interventions; and (ii) reducing the incidence of these infections in district hospitals to 20% by 2025 and 40. % by 2030 [128].

Second, the establishment of an AMR task force at the national level demonstrates Vietnam’s commitment to addressing drug resistance comprehensively. This task force, comprising representatives from four ministries, aims to coordinate efforts in combating AMR [12]. However, challenges persist at the provincial and district levels, where intersectoral coordination remains limited.

Third, Vietnam’s commitment to the One Health approach highlighted its recognition of the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health in combating AMR. The One Health Partnership Framework from 2021 to 2025 and the National Action Plan on One Health exemplify efforts to promote interdisciplinary collaboration [151, 152]. To date, 33 official member partners have been involved, and nearly 100 programs and projects are being prepared and implemented in an effort to support the implementation of the plan under the One Health Partnership Framework [151, 153]. However, the role of the private sector in antibiotic resistance has been mentioned mainly in livestock and poultry production [154].

Fourth, interventions at hospitals and medical facilities, from primary to higher levels, emphasize the importance of appropriate antibiotic use and infection control, particularly to improve antibiotic prescribing practices and reduce the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. For example, the Decision 2115/QD-BYT dated May 11, 2023, already approved “Guidelines for implementing the antibiotic use program for district hospitals” [129]. In 2014, Vietnam approved the National Strategy for Pharmaceutical Industry Development for the period up to 2020 and vision to 2030 [125]. The Plan on AMR in 2023 sets the target of compliance with good practices on infection prevention and control and biosafety, in which provincial and central levels reach at least 40% by 2025 and 70% by 2030 [128].

Fifth, educational policies on drug use in the community started in 2015, but not much involved the private health sector, especially private pharmacies. The Ministry of Health determined that the most important thing to do is to increase people’s awareness about using drugs effectively for themselves and for the community [155]. The National Strategy for AMR Prevention 2023 sets clear goals to raise awareness and understanding of medical and veterinary staff about drug resistance prevention and control, of which the second goal is to increase the correct understanding of drug resistance prevention and control to 60% by 2030 among medical staff [128].

Finally, in Vietnam, the widespread sale of prescription drugs without prescriptions persists despite numerous prohibiting regulations. Challenges include inadequate postinspection mechanisms, an excessive number of pharmacies, and limited human resources within regulatory bodies. Sanctions for violations are also insufficient to deter non-compliance. According to regulations, the act of retailing prescription drugs without a prescription is fined from 200,000 VND to 500,000 VND. For drugs that are not fully, clearly, or accurately prescribed, the fine will be from 1,000,000 VND to 2,000,000 VND [156]. Various decisions and circulars have been issued to enhance control over drug prescriptions and sales, with a focus on reducing antibiotic overuse and associated risks for people and outpatients [114, 123, 130, 131, 157].

Recently, the Ministry of Health went further in antibiotic prescription by introducing electronic prescriptions in 2021 and requiring medical facilities and pharmacies to adopt information technology infrastructure for prescription processing and storage, such as electronic prescriptions [120]. In Circular 27/2021/TT-BYT, medical examination and treatment facilities and drug retail establishments must ensure information technology infrastructure, send electronic prescriptions according to procedures, and store them properly according to regulations [120].

5 Discussion

Global efforts to combat AMR involve multiple strategies across surveillance, medical education, community awareness, the One Health approach, and public‒private partnerships. In Vietnam, these strategies were also implemented, but the extent and effectiveness of these activities varied, with limited evidence to support their impact.

Vietnamese private medical facilities have not been included in the AMR surveillance network, challenging the national and local authorities in AMR controlling the private sector. Though the government has initiated the VNASS nationwide since 2016 to monitor AMR, no private health facility was recruited into this system so far [128]. According to some studies in LMICs, private sector facilities offer better data collection opportunities because of superior resources, and private networks in LMICs can help bridge AMR surveillance gaps [76]. The surveillance network under RAISIN of France could show a good model of involving private hospitals to national AMR control program [145].

While the number and distribution of private pharmacies and drug stores were very high in Vietnam, the knowledge and attitude of the drug sellers regarding AMR was limited, which contributed to the spreading of unnecessary antibiotic use. In the community, these facilities were considered as an informal “fifth level” primary care points (under central, provincial, district and commune levels) [18, 158], with the advantages of convenient opening hours, availability of generic medications, ability to purchase medications in small quantities, and geographic accessibility [159]. According to a report in 2015, the number of registered drug dispensaries was estimated around 66/100,000 people, not including unregistered drug stores, meanwhile, the number of pharmacists was 33.9/100,000 people [140]. This meant that many stores were managed by staff with minimal formal pharmacy training. In some countries, continuing medical education has been applied to improve knowledge and attitudes concerning appropriate antibiotics and AMR [55, 56, 80].

Since 2013, the AMR awareness campaigns have been conducted very frequently, particularly during the World AMR Awareness Week (WAAW), but no evidence of the outcome of these campaigns regarding the public awareness of AMR were officially reported. While the AMR problem is requiring cross-sectoral and systematic interventions at the national and regional levels, many literature reviews reported the efforts to address consumption tended to focus on the individual level [160, 161]. A recent research recognized that the focus on improving knowledge and changing the behavior of individuals has been largely unsuccessful in changing patterns of antibiotic use [160]. Therefore, antibiotic and AMR education program should be on a longer-term basis, both for clinicians and parents, to lower inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rates, as demonstrated in a recent RCT conducted in the US [80].

In the Vietnamese community, knowledge about antibiotics and awareness of the people on AMR were still low, especially in rural areas [140]. Research conducted by Giang et al. highlights the remaining challenges in public awareness and prevention of AMR, which stemmed from their access to convenient pharmaceutical care and affordable prices, self-medication, and the ability of pharmacists to benefit from the sale of antibiotics and other health supplements [19]. The unregulated prescription drug sales in Vietnam are also driven by real demand and high consumer awareness of antibiotics [7, 18]. Despite laws requiring the use of prescription medications [139], antibiotics are still widely sold without prescription in pharmacies and private drug stores. The most commonly purchased antibiotics are broad-spectrum penicillins, such as amoxicillin and ampicillin, and first-generation cephalosporins, such as cephalexin [7, 17].

For the One Health approach, while Vietnam has demonstrated commitment to the One Health Policy through partnerships and national action plans, private sector involvement in AMR prevention and control has remained limited, particularly outside the livestock and poultry farming sector. This underscored the need for expanded roles and collaboration to address AMR comprehensively [154].

The use of PPPs for AMR prevention and control in Vietnam is weak, and PPPs are not recognized as key measures for improving AMR control and prevention in the private health sector. While some private sector stakeholders have shown interest in partnering with the government, challenges such as inappropriate regulations and conflicts of interest hinder effective implementation. A study by Bordier et al. revealed that private medical facilities and the antibiotic business sector are absent from the strategy for monitoring antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use in humans [149]. Addressing these barriers is crucial for harnessing the potential of PPPs for combating AMR.

5.1 Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, there is a reliance on non-peer-reviewed documents, such as workshop presentations, which may introduce bias into the analysis due to the lack of rigorous scrutiny. Additionally, the scope of the literature search using Google searches potentially caused some bias in selection of documents due to the algorithm of Google Search Engine was personalized by the user. Therefore, it might excluded valuable insights from gray literature sources. Furthermore, the selection criteria may limit the breadth of perspectives considered by excluding certain actors within the private healthcare sector. Finally, the study did not incorporate empirical research or statistical analyses to validate the findings, potentially constraining the depth of understanding.

6 Conclusions

The findings of this study highlighted the role of international and national surveillance, education for both health providers and consumers, community awareness campaigns, public‒private partnerships, One-Health approaches to effectively address AMR in the private health sector. Greater investment in medical education, surveillance, one-health approaches, and regulatory enforcement in antibiotic prescription and sales in the private health sector is pivotal for promoting rational antibiotic use and alleviating the burden of AMR. Moreover, fostering public‒private partnerships and community awareness in countries like India could mobilize more resource and expertise to enhance capacity building in AMR management and improve the effectiveness of AMR programs in LMICs such as Vietnam.

6.1 Future activity recommendations

To enhance AMR control in the private health sector of Vietnam, this study recommends following possible strategies. First, an expanded AMR monitoring network involving private medical facilities and hospitals should be established. This should be supported by government policies promoting active participation. Second, interventions in primary healthcare and hospitals, coupled with education on appropriate antibiotic use for private doctors and pharmacies, are needed to improve awareness and quality of diagnosis and treatment. Third, strengthening community awareness through targeted health campaigns and reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescription by promoting electronic prescribing can mitigate AMR risks. Fourth, the government should take high consideration of public‒private partnerships and create incentives for private sector involvement in AMR prevention and control, including investments in research and development. Fifth, the government need to continue the implementation of One Health Policy. A coordinated approach across health, agriculture, and environmental sectors is needed to address AMR comprehensively. And finally, enhancing the regulatory framework for antibiotic control, including postinspection work and enforcement of prescription-only regulations should also be considered to implement in the long term.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- CARB:

-

Combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- CDC:

-

Centre of Disease Control

- EU:

-

European Delegation

- GAPP:

-

Good Antibiotic Prescribing Practices

- GLASS:

-

Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance

- HAI:

-

Healthcare-associated infection

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PPP:

-

Public–private partnerships

- RAISIN:

-

The Réseau d’alerte, d’investigation et de surveillance des infections nosocomiales, Regional Coordination Center for Hospital Infection Control

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

- USD:

-

US Dollar

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WPRACSS:

-

Western Pacific Regional Antibiotic Consumption Survey

- VNASS:

-

Vietnam Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System

- VND:

-

Vietnam Dong

References

WHO. Antibiotic resistance—fact sheet. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance.

Cantón R, Akova M, Langfeld K, Torumkuney D. Relevance of the consensus principles for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in 2022. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;77(1):i2-9.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–55.

Phuong NTK, Hoang TT, Van PH, Tu L, Graham SM, Marais BJ. Encouraging rational antibiotic use in childhood pneumonia: a focus on Vietnam and the Western Pacific region. Pneumonia. 2017;9:7.

Rony MKK, Sharmi PD, Alamgir HM. Addressing antimicrobial resistance in low and middle-income countries: overcoming challenges and implementing effective strategies. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30:101896–902.

Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E3463–70.

Alsan M, Schoemaker L, Eggleston K, Kammili N, Kolli P, Bhattacharya J. Out-of-pocket health expenditures and antimicrobial resistance in low-income and middle-income countries: an economic analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1203–10.

Li J, Zhou P, Wang J, Li H, Xu H, Meng Y, et al. Worldwide dispensing of non-prescription antibiotics in community pharmacies and associated factors: a mixed- methods systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23:E361–70.

Granlund D, Zykova YV. Can private provision of primary care contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance? A study of antibiotic prescription in Sweden. PharmacoEconomics. 2021;5:187–95.

Nga DTT, Chuc NTK, Hoa NP, Hoa NQ, Nguyen NTT, Loan HT, et al. Antibiotic sales in rural and urban pharmacies in northern Vietnam: an observational study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;15:6.

MOH. National Action Plan on combatting drug resistance in the period 2013–2020. Approved with the Decision No. 2174/QD-BYT dated 21st June 2013 by Minister of Health of Viet Nam. 2013.

CDC. Combating Antimicrobial Resistance in Vietnam. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/solutions-initiative/stories/tracking-resistance-in-vietnam.html. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Nguyen T, Do T, Nguyen H, Nguyen C, Meyer J, Godman B, et al. A national survey of dispensing practice and customer knowledge on antibiotic use in Vietnam and the implications. Antibiotics. 2022;11:1091.

Mitchell MEV, Alders R, Unger F, Nguyen-Viet H, Le TTH, Toribio J-A. The challenges of investigating antimicrobial resistance in Vietnam—what benefits does a One Health approach offer the animal and human health sectors? BMC Public Health. 2020;20:213.

McKinn S, Trinh DH, Drabarek D, Trieu TT, Nguyen PT, Cao TH, et al. Drivers of antibiotic use in Vietnam: implications for designing community interventions. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6: e005875.

Nguyen NV, Do NTT, Nguyen CTK, Tran TK, Ho PD, Nguyen HH, et al. Community-level consumption of antibiotics according to the AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) classification in rural Vietnam. JAC-Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2:dlaa048.

Dat VQ, Toan PK, van Doorn HR, Thwaites CL, Nadjm B. Purchase and use of antimicrobials in the hospital sector of Vietnam, a lower middle-income country with an emerging pharmaceuticals market. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0240830.

Pham GN, Dang TTH, Nguyen T-A, Zawahir S, Le HTT, Negin J, et al. Health system barriers to the implementation of the national action plan to combat antimicrobial resistance in Vietnam: a scoping review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2024;13:12.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143.

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6:245.

van Enst WA, Scholten RJPM, Whiting P, Zwinderman AH, Hooft L. Meta-epidemiologic analysis indicates that MEDLINE searches are sufficient for diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1192–9.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, Kramer BMR. Comparing the coverage, recall, and precision of searches for 120 systematic reviews in Embase, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar: a prospective study. Syst Rev. 2016;5:39.

Piasecki J, Waligora M, Dranseika V. Google search as an additional source in systematic reviews. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018;24:809–10.

Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015;4:138.

Briscoe S, Abbott R, Lawal H, Shaw L, Coon JT. Feasibility and desirability of screening search results from Google Search exhaustively for systematic reviews: a cross-case analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2023;14:427–37.

Klinton J. The private health sector: an operational definition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Nguyen MP, Wilson A. How could private healthcare better contribute to healthcare coverage in Vietnam? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6:305–8.

Liverani M, Oliveira Hashiguchi L, Khan M, Coker R. Antimicrobial resistance and the private sector in Southeast Asia. In: Jamrozik E, Selgelid M, editors. Ethics and drug resistance: collective responsibility for global public health. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 75–87.

Viet Nam national assembly. Law on medical examination and treatment (No. 40/2009/QH12). 2009.

National assembly. Law No. 15/2023/QH15 on medical examination and treatment. 2023.

Viet Nam national assembly. Law on pharmacy (No. 105/2016/QH13). 2016.

Kliemann B, Levin A, Moura M, Boszczowski I, Lewis J. Socioeconomic determinants of antibiotic consumption in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil: the effect of restricting over-the-counter sales. PLOS ONE. 2016;11: e0167885.

Baubie K, Shaughnessy C, Kostiuk L, Joseph M, Safdar N, Singh S, et al. Evaluating antibiotic stewardship in a tertiary care hospital in Kerala, India: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2019;9: e026193.

Santa-Ana-Tellez Y, Mantel-Teeuwisse A, Leufkens H, Wirtz V. Effects of over-the-counter sales restriction of antibiotics on substitution with medicines for symptoms relief of cold in Mexico and Brazil: time series analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:1291–6.

Binda F, Tebano G, Kallen M, ten Oever J, Hulscher M, Schouten J, et al. Nationwide survey of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs in France. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50:414–22.

Moura M, Boszczowski I, Blaque M, Mussarelli R, Fossaluza V, Pierrotti L, et al. Effect on antimicrobial resistance of a policy restricting over-the-counter antimicrobial sales in a large metropolitan Area, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:180–7.

Nair M, Mahajan R, Burza S, Zeegers M. Behavioural interventions to address rational use of antibiotics in outpatient settings of low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26:504–17.

Singh S, Chua A, Tan S, Tam C, Hsu L, Legido-Quigley H. Combating antimicrobial resistance in Singapore: a qualitative study exploring the policy context, challenges, facilitators, and proposed strategies. Antibiotics. 2019;8:201.

Dumartin C, Rogues A-M, Amadeo B, Pefau M, Venier A-G, Parneix P, et al. Antibiotic stewardship programmes: legal framework and structure and process indicator in Southwestern French hospitals, 2005–2008. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:123–8.

Onwunduba A, Ekwunife O, Onyilogwu E. Impact of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing intervention on non-prescription dispensing of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections in private community pharmacies in Nigeria: a cluster randomize d controlle d trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;127:137–43.

Darwish R, Matar S, Snaineh A, Alsharif M, Yahia A, Mustafa H, et al. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship on antibiogram, consumption and incidence of multi drug resistance. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:916.

Shen L, Wei X, Yin J, Haley D, Sun Q, Lundborg C. Interventions to optimize the use of antibiotics in China: A scoping review of evidence from humans, animals, and the environment from a One Health perspective. ONE Health. 2022;14:100388.

Lui L, Wong L, Chen H, Yung R, Working Grp Collaboration CHP Priv. Antibiogram data from private hospitals in Hong Kong: 6-year retrospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2022;28:140–51.

Walia K, Ohri V, Mathai D. Antimicrobial stewardship programme (AMSP) practices in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:130–8.

Sharma S, Kumari N, Sengupta R, Malhotra Y, Bhartia S. Rationalising antibiotic use after low-risk vaginal deliveries in a hospital setting in India. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10: e001413.

Chan J, Nguyen V, Tran T, Nguyen N, Do N, Doorn H, et al. Point-of-care testing in private pharmacy and drug retail settings: a narrative review. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:551.

Moura M, Boszczowski I, Mortari N, Barrozo L, Neto F, Lobo R, et al. The impact of restricting over-the-counter sales of antimicrobial drugs preliminary analysis of national data. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94: e1605.

McCombe G, Conneally N, Harrold A, Butt A, Behan W, Molony D, et al. How does the introduction of free GP care for children impact on GP service provision? A qualitative study of GPs. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188:1245–9.

Ganesan V, Sundaramurthy R, Thiruvanamalai R, Sivakumar V, Udayasankar S, Arunagiri R, et al. Device-associated hospital-acquired infections: does active surveillance with bundle care offer a pathway to minimize them? Cureus J Med Sci. 2021;13: e19331.

Peiffer-Smadja N, Allison R, Jones L, Holmes A, Patel P, Lecky D, et al. Preventing and managing urinary tract infections: enhancing the role of community pharmacists-a mixed methods study. Antibiotics. 2020;9:583.

Pinto L, Udwadia Z. “Universal” access for MDR-TB limited without the involvement of the private sector [Correspondence]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:851–851.

Yin X, Gong Y, Yang C, Tu X, Liu W, Cao S, et al. A comparison of quality of community health services between public and private community health centers in urban China. Med Care. 2015;53:888.

Singh S, Charani E, Devi S, Sharma A, Edathadathil F, Kumar A, et al. A road-map for addressing antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries: lessons learnt from the public private participation and co-designed antimicrobial stewardship programme in the State of Kerala, India. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:32–32.

Årdal C, Blix HS, Plahte J, Røttingen J-A. An antibiotic’s journey from marketing authorization to use, Norway. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:220–6.

Wirtz VJ, Herrera-Patino JJ, Santa-Ana-Tellez Y, Dreser A, Elseviers M, Vander Stichele RH. Analysing policy interventions to prohibit over-the-counter antibiotic sales in four Latin American countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:665–73.

Collignon P, Beggs JJ, Walsh TR, Gandra S, Laxminarayan R. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2:e398-405.

Sommanustweechai A, Chanvatik S, Sermsinsiri V, Sivilaikul S, Patcharanarumol W, Yeung S, et al. Antibiotic distribution channels in Thailand: results of key-informant interviews, reviews of drug regulations and database searches. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:101–9.

Landstedt K, Sharma A, Johansson F, Stålsby Lundborg C, Sharma M. Antibiotic prescriptions for inpatients having non-bacterial diagnosis at medicine departments of two private sector hospitals in Madhya Pradesh, India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012974–e012974.

Ryu S, Head MG, Kim BI, Hwang J, Cho E-H. Are we investing wisely? A systematic analysis of nationally funded antimicrobial resistance projects in Republic of Korea 2003–2013. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2016;6:90–4.

Yimer SA, Holm-Hansen C, Bjune G. Assessment of knowledge and practice of private practitioners regarding tuberculosis control in Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:13–9.

Rickard J. Bacterial resistance in surgical infections in low-resource settings. Surg Infect. 2020;21:509–15.

Nizame FA, Shoaib DM, Rousham EK, Akter S, Islam MA, Khan AA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to adherence to national drug policies on antibiotic prescribing and dispensing in Bangladesh. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14:85–85.

Metz M, Shlaes DM. Eight more ways to deal with antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4253–6.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Lagarde M, Blaauw D. Levels and determinants of overprescribing of antibiotics in the public and private primary care sectors in South Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8:e012374–e012374.

Theuretzbacher U, Årdal C, Harbarth S. Linking sustainable use policies to novel economic incentives to stimulate antibiotic research and development. Infect Dis Rep. 2017;9:6836.

Luepke KH, Suda KJ, Boucher H, Russo RL, Bonney MW, Hunt TD, et al. Past, present, and future of antibacterial economics: increasing bacterial resistance, limited antibiotic pipeline, and societal implications. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2017;37:71–84.

Shet A, Sundaresan S, Forsberg BC. Pharmacy-based dispensing of antimicrobial agents without prescription in India: appropriateness and cost burden in the private sector. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:55–55.

Akulayi L, Alum A, Andrada A, Archer J, Arogundade ED, Auko E, et al. Private sector role, readiness and performance for malaria case management in Uganda, 2015. Malar J. 2017;16:219–219.

Al-Omari A, Al Mutair A, Alhumaid S, Salih S, Alanazi A, Albarsan H, et al. The impact of antimicrobial stewardship program implementation at four tertiary private hospitals: results of a five-years pre-post analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:95–95.

Rutta E, Tarimo A, Delmotte E, James I, Mwakisu S, Kasembe D, et al. Understanding private retail drug outlet dispenser knowledge and practices in tuberculosis care in Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:1108–13.

Rehman MU, Tariq NA, Ahmed M, Ahmad M, Zahid A, Chaudhry Q, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of common cold and its management among doctors of Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad JAMC. 2016;28:523–7.

Montoya A, Mody L. Common infections in nursing homes: a review of current issues and challenges. Aging Health. 2011;7:889–99.

Gandra S, Merchant AT, Laxminarayan R. A role for private sector laboratories in public health surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:709–12.

Lee MHM, Pan DST, Huang JH, Chen MI-C, Chong JWC, Goh EH, et al. Results from a patient-based health education intervention in reducing antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infections in the private sector primary care setting in Singapore. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02257-16.

Henry W. Efficacy of a patient-based health education intervention in reducing antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infections in the private sector primary care setting in Singapore. 2015.

Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Affran-Bonful H, Bart-Plange C, Cundill B, Gyapong M, et al. The impact of providing rapid diagnostic malaria tests on fever management in the private retail sector in Ghana: a cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2015;350: h1019.

Goggin K, Hurley EA, Lee BR, Bradley-Ewing A, Bickford C, Pina K, et al. Let’s talk about antibiotics: a randomised trial of two interventions to reduce antibiotic misuse. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e049258.

World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS). 2023. https://www.who.int/initiatives/glass. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Dumartin C, Rogues A-M, Amadéo B, Péfau M, Venier A-G, Parneix P, et al. Antibiotic usage in south-western French hospitals: trends and association with antibiotic stewardship measures. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1631–7.

The White House. Executive order—combating antibiotic resistant bacteria. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/executive-order_ar.pdf. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

World Health Organization. Global leaders group on antimicrobial resistance. 2020. https://www.who.int/groups/one-health-global-leaders-group-on-antimicrobial-resistance. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

AMR Leaders. Global leaders group on antimicrobial resistance—members. 2021. https://www.amrleaders.org/members. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

United Nations. Call to action on antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—2021. 2021.

ICMRA. Antimicrobial resistance best practices working group report and case studies. 2022.

NIH. Antimicrobial Resistance Diagnostic Challenge. 2020. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/AMRChallenge. Accessed 28 Dec 2023.

European Commission. EU action on antimicrobial resistance—European Commission. https://health.ec.europa.eu/antimicrobial-resistance/eu-action-antimicrobial-resistance_en. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

Cleaveland S, Sharp J, Abela-Ridder B, Allan KJ, Buza J, Crump JA, et al. One Health contributions towards more effective and equitable approaches to health in low- and middle-income countries. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372:20160168.

Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M. The one health approach-why is it so important? Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4:88.

Yopa DS, Massom DM, Kiki GM, Sophie RW, Fasine S, Thiam O, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of one health strategies in developing countries: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1252428.

CDC. Join the AMR challenge. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/intl-activities/amr-challenge.html. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

European Commission. Commission notice—EU Guidelines for the prudent use of antimicrobials in human health.

EU Council. Tackling antimicrobial resistance: Council adopts recommendation. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/06/13/tackling-antimicrobial-resistance-council-adopts-recommendation/. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

Australian Government. National AMR Strategy. Antimicrobial resistance. 2021. https://www.amr.gov.au/australias-response/national-amr-strategy. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

Australian Government. Australia’s antimicrobial resistance strategy—2020 and beyond. 2020.

Australian Government. Australia’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy – 2020 and Beyond. Canberra: Department of Health, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment; 2019.

Australian Government. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Health Care, Australian Commission on safety and quality in health care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/antimicrobial-stewardship-australian-health-care. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

Hammerum AM, Heuer OE, Emborg H-D, Bagger-Skjøt L, Jensen VF, Rogues A-M, et al. Danish integrated antimicrobial resistance monitoring and research program. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1633–9.

Chua AQ, Kwa AL-H, Tan TY, Legido-Quigley H, Hsu LY. Ten-year narrative review on antimicrobial resistance in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2019;60:387–96.

UN. Call to action on antimicrobial resistance 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-07-2021-call-to-action-on-antimicrobial-resistance-2021. Accessed 25 Dec 2023.

Joshi MP, Hafner T, Twesigye G, Ndiaye A, Kiggundu R, Mekonnen N, et al. Strengthening multisectoral coordination on antimicrobial resistance: a landscape analysis of efforts in 11 countries. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14:27.

Suzuki S. A view on 20 years of antimicrobial resistance in Japan by two national surveillance systems: the national epidemiological surveillance of infectious diseases and Japan Nosocomial infections surveillance. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1189.

Canada PHA of. Antimicrobial resistance and use in Canada: A federal framework for action. 2014. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/antibiotic-antimicrobial-resistance/antimicrobial-resistance-use-canada-federal-framework-action.html. Accessed 11 Dec 2023.

Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham. CME on good antibiotic prescription practices held at Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences. 2016. https://www.amrita.edu/news/cme-on-good-antibiotic-prescription-practices-held-at-amrita-institute-of-medical-sciences/. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Eastmure E, Fraser A, Al-Haboubi M, Bennani H, Black N, Blake L, et al. National and Local Implementation of the UK Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Strategy, 2013–2018.

Nogrady B. The fight against antimicrobial resistance. Nature. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03912-8.

Ryu S. The new Korean action plan for containment of antimicrobial resistance. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;8:70–3.

Lagarde M, Blaauw D. Overtreatment and benevolent provider moral hazard: evidence from South African doctors. J Dev Econ. 2022;158: 102917.

Government of Vietnam. Nghị định54/2017/NĐ-CP Quy định một số điều và biện pháp thi hành Luật dược. 2017.

Government of Vietnam. Nghị định109/2016/NĐ-CP Quy định cấp chứng chỉ hành nghề đối với người hành nghề và cấp giấy phép hoạt động đối với cơ sở khám bệnh, chữa bệnh. 2016.

Government of Vietnam. Nghị định 131/2020/NĐ-CP Quy định về tổ chức, hoạt động dược lâm sàng của cơ sở khám bệnh, chữa bệnh. 2020.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư05/2016/TT-BYT Quy định kê đơn thuốc trong điều trị ngoại trú. 2016.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư21/2013/TT-BYT Quy định về tổ chức và hoạt động của Hội đồng thuốc và điều trị trong Bệnh viện. 2013.

Government of Vietnam. Thông tư 02/2018/TT-BYT Quy định thực hành tốt cơ sở bán lẻ thuốc. 2018.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 04/2022/TT-BYT Sửa đổi, bổ sung một số điều của Thông tư số 52/2017/TT-BYT ngày 29 tháng 12 năm 2017, Thông thư 18/2018-TT-BYT. 2022.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 12/2020/TT-BYT Sửa đổi, bổ sung một số điều của Thông tư số 02/2018/TT-BYT ngày 22 tháng 01 năm 2018 của Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế quy định về thực hành tốt cơ sở bán lẻ thuốc. 2020.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 18/2018/TT-BYT Sửa đổi, bổ sung một số điều của Thông tư số 52/2017/TT-BYT ngày 29 tháng 12 năm 2017 quy định về đơn thuốc và kê đơn thuốc hóa dược, sinh phẩm trong điều trị ngoại trú. 2018.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 27/2021/TT-BYT Quy định kê đơn thuốc bằng hình thức điện tử. 2021.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 31/2012/TT-BYT Hướng dẫn hoạt động dược lâm sàng trong bệnh viện. 2012.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 44/2018/TT-BYT Quy định kê đơn thuốc cổ truyền, thuốc dược liệu và kê đơn kết hợp thuốc cổ truyền, thuốc dược liệu với thuốc hóa dược. 2018.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 52/2017/TT-BYT Quy định về đơn thuốc và việc kê đơn thuốc hóa dược sinh phẩm trong điều trị ngoại trú. 2017.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Thông tư 16/2018/TT-BYT quy định về kiểm soát nhiễm khuẩn trong các cơ sở khám bệnh, chữa bệnh. 2018.

Government of Vietnam. Quyết định 68/QĐ-TTg Phê duyệt Chiến lược quốc gia phát triển ngành Dược Việt Nam giai đoạn đến năm 2020 và tầm nhìn đến năm 2030 do Thủ tưởng Chính phủ ban hành. 2014.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 708/QĐ-BYT Ban hành tài liệu chuyên môn “Hướng dẫn sử dụng kháng sinh.” 2015.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 772/QĐ-BYT Ban hành tài liệu “Hướng dẫn thực hiện quản lý sử dụng kháng sinh trong bệnh viện.” 2016.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 1121/QĐ-TTg Phê duyệt chiến lược quốc gia về phòng, chống kháng thuốc tại Việt Nam giai đoạn 2023 - 2030, tầm nhìn đến năm 2045. 2023.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 2115/QĐ-BYT Ban hành tài liệu chuyên môn “Hướng dẫn thực hiện chương trình sử dụng kháng sinh dành cho bệnh viện tuyến huyện.” 2023.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 4041/QĐ-BYT Phê duyệt Đề án tăng cường kiểm soát kê đơn thuốc và bán thuốc kê đơn giai đoạn 2017–2020 do Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế ban hành. 2017.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 4448/QĐ-BYT Ban hành Kế hoạch triển khai Đề án tăng cường kiểm soát kê đơn thuốc và bán thuốc kê đơn giai đoạn 2017–2020 theo Quyết định số 4041/QĐ-BYT. 2017.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 5631/QĐ-BYT Ban hành tài liệu “Hướng dẫn thực hành quản lý sử dụng kháng sinh trong bệnh viện.” 2020.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định số 6211/QĐ-BYT về việc thiết lập và quy định chức năng, nhiệm vụ của mạng lưới giám sát vi khuẩn kháng thuốc trong các cơ sở khám, chữa bệnh. 2016.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 3391/QD-BYT về việc Thành lập Đơn vị giám sát kháng thuốc Quốc gia. 2015.

MARD, MOH. The Viet Nam one health strategic plan for zoonotic diseases 2016–2020. 2016. https://onehealth.org.vn/upload/upload/National%20One%20Health%20Strategic%20Plan%20for%20Zoonotic%20Diseases_VN.pdf. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Government of Vietnam. Chiến lược quốc gia về phòng, chống kháng thuốc tại Việt Nam giai đoạn 2023 - 2030, tầm nhìn đến năm 2045 (Ban hành kèm theo Quyết định 1121/QĐ-TTg). 2023.

Government of Vietnam. Chỉ thị 23/CT-TTg Về việc tăng cường quản lý, kết nối các cơ sở cung ứng thuốc. 2018.

Nguyen KV. Situation Analysis on Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Vietnam, 2010, GARP – Việt Nam. Washington. 2010.

Carrique-Mas JJ, Choisy M, Van Cuong N, Thwaites G, Baker S. An estimation of total antimicrobial usage in humans and animals in Vietnam. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:16.

Larsson M, Nguyen HQ, Olson L, Tran TK, Nguyen TV, Nguyen CTK. Multi-drug resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae among children in rural Vietnam more than doubled from 1999 to 2014. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:1916–23.

Thang Nguyen. Selling antibiotics without a prescription in the community in Vietnam (Antibiotic Resistance Conference Document 26.11.2020). Vietnamese language. 2020.

Patel J, Harant A, Fernandes G, Mwamelo AJ, Hein W, Dekker D, et al. Measuring the global response to antimicrobial resistance, 2020–21: a systematic governance analysis of 114 countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23:706–18.

World Health Organization. People-centred approach to addressing antimicrobial resistance in human health: WHO core package of interventions to support national action plans. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

The RAISIN Working Group C. “RAISIN” – a national programme for early warning, investigation and surveillance of healthcare-associated infection in France. Eurosurveillance. 2009;14:19408.

United States Government. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria (CARB). 2020.

Morikane K. Infection control in healthcare settings in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:86–90.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Quyết định 127/QĐ-BYT Về việc ban hành Hướng dẫn thực hiện giám sát quốc gia về kháng kháng sinh. 2019.

Bordier M, Binot A, Pauchard Q, Nguyen DT, Trung TN, Fortané N, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Vietnam: moving towards a One Health surveillance system. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1136.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Antibiotic resistance surveillance report in Vietnam 2020. 2023.

Ministry of Heath Portal. Diễn đàn cấp cao thường niên về Một sức khỏe phòng, chống dịch bệnh từ động vật sang người giai đoạn 2021–2025. 2023. https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-bo/-/asset_publisher/TW6LTp1ZtwaN/content/dien-an-cap-cao-thuong-nien-ve-mot-suc-khoe-phong-chong-dich-benh-tu-ong-vat-sang-nguoi-giai-oan-2021-2025. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Nguyen-Viet H, Lam S, Nguyen-Mai H, Trang DT, Phuong VT, Tuan NDA, et al. Decades of emerging infectious disease, food safety, and antimicrobial resistance response in Vietnam: the role of One Health. One Health Amst Neth. 2022;14:100361–100361.

MARD portal. Ký kết khung đối tác ‘Một sức khỏe’ giai đoạn 2021–2025. 2021. https://www.mard.gov.vn/Pages/ky-ket-khung-doi-tac-%E2%80%98mot-suc-khoe%E2%80%99-giai-doan-2021-2025.aspx. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

OneHealth Viet Nam. Public-Private cooperation in preventing antibiotic resistance in livestock. 2023. https://onehealth.org.vn/public-private-cooperation-in-preventing-antibiotic-resistance-in-livestock.new. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Dùng thuốc kháng sinh phải theo chỉ định của bác sĩ. 2019. https://moh.gov.vn/chuong-trinh-muc-tieu-quoc-gia/-/asset_publisher/7ng11fEWgASC/content/dung-thuoc-khang-sinh-phai-theo-chi-inh-cua-bac--1. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

Ministry of Health of Vietnam. Đến lúc phải siết chặt kê đơn và bán thuốc kê đơn. 2017. https://moh.gov.vn/tin-tong-hop/-/asset_publisher/k206Q9qkZOqn/content/-en-luc-phai-siet-chat-ke-on-va-ban-thuoc-ke-on?inheritRedirect=false. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

People Public Security Online. Phải có chế tài riêng để xử phạt vi phạm về kê đơn, bán thuốc kháng sinh sai quy định. 2020. https://cand.com.vn/y-te/Phai-co-che-tai-rieng-de-xu-phat-vi-pham-ve-ke-don-ban-thuoc-khang-sinh-sai-quy-dinh-i589647/. Accessed 29 Dec 2023.

WHO/OIE/FAO. Global database for the tripartite antimicrobial resistance (AMR) country self-assessment Survey (TrACSS). https://amrcountryprogress.org/#/map-view.

Vu TVD, Do TTN, Rydell U, Nilsson LE, Olson L, Larsson M, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and antibiotic consumption results from 16 hospitals in Viet Nam: The VINARES project 2012–2013. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;18:269–78.

Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax. 2012;67:71.

Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, Fakhran S, Balk R, Bramley AM, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–27.

Torres N, Solomon V, Middleton L. Pharmacists’ practices for non-prescribed antibiotic dispensing in Mozambique. Pharm Pract. 2020;18:1965.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the leaders of Department of International Health and Medical Service Administration of Ministry of Health of Viet Nam. We also thank to Ms. Nguyen Thuy Linh, Vietnam National Cancer Hospital for collecting documents in Vietnamese.

Funding

This study was financially funded by FHI 360 under the project “Fleming Fund for Antibiotic-resistant Surveillance System in Vietnam (Fleming Fund), number 1302.0003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, LTNT, ADD, and MHN; methodology, LTNT, ADD; formal analysis, LTNT, ADD, MHN, GHN and GVT; writing—original draft preparation, LTNT, ADD, MHN; writing—revising and editing, GHN, GVT, and ADD; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted on the basis of a literature review only; therefore, we did not apply the proposal to the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Trinh, L.T.N., Do, A.D., Nguyen, M.H. et al. A scoping review on best practices of antibiotic resistance control in the private health sector and a case study in Vietnam. Discov Public Health 21, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00174-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00174-1