Abstract

Purpose

The implementation of occupational health and safety (OHS) measures among healthcare workers in Tanzania is suboptimal, mainly due to a lack of adequate resources. This study aimed to map the available research and identify research gaps on occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted by searching relevant articles in MEDLINE, Scopus, Science Direct and Web of Science electronic databases. A total of 29 studies were included, and the data were extracted from these studies.

Results

Healthcare workers in Tanzania are exposed to biological, psychosocial, ergonomics, physical and chemical hazards. The majority of the literature involved biological hazards (71%), and research on other hazards was limited.

Conclusion

OHS need to become a priority public health issue to protect healthcare workers in Tanzania. More research is needed to understand the determinants of this problem in Tanzania.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The World Health Organization estimated a total of 65.1 million healthcare workers in 2020, projecting to a 29% growth by 2030 [1]. There is a global shortage of healthcare workers and this is high in developing countries [2]. Despite the shortage, healthcare workers experience occupational health injuries and diseases which pose safety risk and hence reduce their performance [3]. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO) report, work-related diseases accounted for 2.58 million (89%) of the total estimated deaths attributed to work in 2019 while occupational injuries made up the remaining [4]. The review from O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health suggests that every 15 s, a worker dies and every day, 6,300 people die as a result of occupational injuries or work-related diseases [5].

The global prevalence of any form of workplace violence to healthcare workers is 61.9% with verbal abuse being the most common form [6]. A systematic review study found that the prevalence of low back pain is higher among the health care workers (54.8%) and stress, lack of physical exercise, patient related factors, and body position at work and were the risk factors [7]. Communicable diseases are more common in low-income countries, constituting slightly more than 30% of work-related mortality in the African region compared to less than 5% in high-income countries and the attributable fraction for infectious diseases was highest for women in both high-income countries and other WHO regions [8].

Healthcare workers face diverse hazards, including exposure to infectious pathogens such as COVID-19, hepatitis B, HIV, and tuberculosis, as well as ergonomic strains leading to musculoskeletal injuries such as back pain [9]. The demanding nature of their work contributes to mental health challenges such as burnout, stress, and depression [10]. Chemical exposures, from disinfectants to latex in gloves and from antineoplastic drugs, pose additional risks, while physical hazards such as radiation, slips, falls, and noise further emphasize the need for comprehensive safety measures in healthcare settings [11]. The World Health Assembly Resolution WHA72.6 on Patient Safety prioritizes the occupational health and safety of healthcare workers to improve their physical and mental health, thus reducing absenteeism, attrition and suboptimal outcomes [12]. However, the implementation of occupational health and safety measures in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has been hampered by limited resources [13].

The benefits of implementing occupational and health safety measures cannot be underestimated compared to the greater financial burden that may be incurred for the compensation and treatment of healthcare workers (HWCs) who experience disease or injury while at work [14]. Furthermore, protecting HCWs improves the quality of the services provided to patients and helps to minimize the waste of resources for hospitals [15]. Healthy and happy healthcare workers have a better quality of life, a lower risk of exposure to hazards and increased work productivity [16].

Recognizing that workers are exposed to a range of workplace hazards and risks, the government of Tanzania established the Occupational Health and Safety Policy to provide guidance on the prevention, management and rehabilitation of occupational health and safety at work places to promote the productivity and profitability of their work [17]. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 2003 provided the legal framework for occupational health and safety in Tanzania and established the responsibilities of employers, workers, and the government to ensure safe and healthy working conditions. To protect workers from any hazardous exposure, as shown in part VI, Sect. 60–62 of this Act requires the employer to conduct regular (annually or at any time as per special need) risk assessments and provide the report to the chief inspector for action [18]. Limited resources make it difficult to effectively monitor and control workplace hazards [13].

To ensure occupational health and safety in health facilities, it is important to understand the magnitude of the problem. The majority of the literature on occupational hazards among health care workers is from developed countries, and a few is from LMICs, including Tanzania [19]. The findings from other settings cannot be generalized because exposures are likely to differ due to differences in social demographics and legislation. There is a need to determine the scope and volume of available research conducted on this topic in Tanzania and to identify any research gaps. Focusing on the health and well-being of healthcare workers in Tanzania will improve the health outcomes of the broader population in line with SDG 3's target to achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to map and identify the research gap in the literature on exposure to occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania, informing policymakers to improve the safety of healthcare workers.

2 Study area

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country located in East African region and has the largest total surface area of 947,300 sq. km and a population size of 61.7 M, 51% of them being female. It is bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the North, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the West and Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to the South; the country’s eastern border lies in the Indian Ocean which has a coastline of 1,424 km. [20]. Tanzania has a workforce of 126,925 healthcare workers, equivalent to 36.4 percent of all (348,923) employees needed in the health sector [21] to provide services to 12,198 operating health facilities ranging from Hospitals (4%), Health centers (10%), Dispensary (66%), Clinics (8%) and Health laboratories (12%); of the total facilities, 40% are owned by the private [22]. The healthcare workers in Tanzania are at risk of being exposed to HIV, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and other occupational hazards. Recent reports indicate that the prevalence of HIV in Tanzania is 4.5 [23] and the prevalence of hepatitis B is 6.91 [24] while the prevalence of TB is 208/100,000 [25]. Moreover, a recent study in Tanzania indicated that there was an increasing trend in both fatal and nonfatal work-related injuries reported to workers’ compensation funds from 2016 to 2019, and motor traffic accidents, machine faults and falls were the most reported causes of musculoskeletal disorders [80]. The presence of these risks and many others indicate that healthcare worker’s safety in Tanzania is an issue of concern. This study aims to identify the research gap in the literature on exposure to occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania and propose solutions.

3 Methods

This review was conducted according to the methodological framework for scoping reviews outlined by Arksey and O’Malley, Levac et al. [26], Colquhan et al. [27], and The Joanna Briggs Institute [28]. The study is reported under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines[29]. This study was guided by the research question ‘What is known from the literature about exposure to occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania?’.

3.1 Search strategy

The key terms relating to the research question were identified as follows: ‘health personnel’, ‘health care workers’, ‘health workers’, ‘health professionals’, ‘doctors’, ‘nurses’, ‘laboratory workers’, ‘occupational health’, ‘occupational risks’, ‘occupational hazards’, ‘occupational diseases’, ‘occupational accidents’, ‘occupational injuries’, and ‘Tanzania’. The search strategy was adopted from previous study [13] and improved by the research team in consultation with an academic librarian. Using these key terms and their associated mapped subject headings and MeSH terms, searches were conducted in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, Scopus, Science Direct and Web of Science. The search was completed on 20 March 2024, and articles published in the English language were the only limits applied to the searches to maintain a breadth of coverage. The bibliographies of the included studies were also checked to ensure that all relevant studies had been included in the review. Gray literature was not included.

3.2 Study selection

All Studies from the inception of the databases till 20 March 2024, were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) were conducted in Tanzania, (2) were healthcare workers as classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) [30], (3) were exposed to occupational hazards, (4) were observational or experimental studies, and (5) were published in English. After removing duplicates, one reviewer (DL) assessed the articles by title and abstract and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to select the full-text articles to be retrieved. Any uncertainties related to study selection at this stage were discussed with the research team until a consensus was reached. Full-text articles were then screened independently by two reviewers (DL and SSK) to finalize their inclusion in the review. Any disagreement regarding the determination of study inclusion in the review at this stage was resolved by consulting a third reviewer (JM). Manual searches of the reference list of the included studies were also conducted.

3.3 Charting of the data

The data were extracted from the studies and charted on a table by one reviewer (DL). This included the author, year of publication, title, study population, study design, methods and key findings. A second reviewer (SSK) then extracted the data from all (29) studies using the data charting form to ensure that the data extraction approach was consistent with the research question and study aims.

3.4 Collating and summarizing the results

The study characteristics, which included the article source information, study participant characteristics, the topic researched, and the key study outcomes, are described in the figures. A thematic analysis was then carried out, and the studies were sorted into occupational hazard groups and types of exposure based on the WHO classification of occupational hazards in health care workers [26]. These two steps assisted in identifying the dominant areas of research, key variables and any research gaps. The findings of this research were described as a narrative review.

4 Results

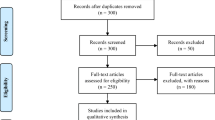

The database searches identified 488 articles, with an additional 26 articles identified from a manual search of the reference lists (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 507 articles were screened by title, followed by the abstracts of 116 articles. A review of the abstracts resulted in 103 articles for full-text examination, 29 of which met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Table 1).

Table 1 indicates study characteristics on occupational hazards faced by healthcare professionals in Tanzania. 29 articles were fully reviewed and analyzed to highlight the risks of biological, psychosocial, ergonomic, physical and chemical hazards.

The included studies were published between 1997 and 2024, with one study published in 1997, 2 studies published between 2005 and 2009, 4 studies published between 2010 and 2014, 13 studies published between 2015 and 2019, and 12 studies published between 2020 and 2024 (Fig. 2). The type of study design was cross-sectional (25, 86%), mixed (3, 10%) or retrospective (1, 4%), as shown in Fig. 3.

In these studies, all participants were healthcare workers, and 66% (19/29) of the studies reported 5596 HCWs by their cadre; nurses (48%) composed the majority of participants, followed by clinicians (21%), as shown in Fig. 4. Twenty-four (83%) studies reported the type of facilities where the research was conducted: zonal referral hospitals (14), regional referral hospitals (35), district hospitals (86), health centers (225) and dispensaries (213), as shown in Fig. 5. The occupational exposure of healthcare workers were; 71% for biological, 14% for psychosocial 6% for ergonomic and physical and 3% for chemical hazards (Fig. 6).

5 Discussion

This study aimed to map and synthesize the available research on occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania. The research conducted on this topic is quite substantial, as evidenced by the 29 articles included in this review. However, most (71%) of these studies involved biological hazards, and research on the other types of hazards was minimal. The findings of this review also show that research on occupational hazards in Tanzania has increased considerably in the last decade, perhaps indicating an increasing recognition of the occupational health and safety of healthcare workers in the country. The occupational exposure of healthcare workers were: 71% for biological, 14% for psychosocial 6% for ergonomic and physical and 3% for chemical hazards (Fig. 6).

5.1 Biological exposure

The most common pathogen mentioned by the literature on biological hazards concerns HIV and hepatitis B transmission through needlestick injuries and mucocutaneous splashing (Table 1). Like those in other sub-Saharan African countries, healthcare workers in Tanzania are at increased risk of blood-borne infection due to needlestick and mucocutaneous splashes [31]. In our research, a total of 8 articles variably reported the prevalence of occupational exposure to needlestick injuries and mucocutaneous splashing, with most (6; 75%) reporting the prevalence in the past year, one in the previous six months and one for the entire career. The prevalence of needlestick injuries and mucocutaneous splashes in the previous year varied widely, from 27.1% to 59.2%[32,33,34,35,36,37]. A systematic review indicated that the global pooled prevalence of blood and body fluids among healthcare workers during their career time and in the previous year accounted for 56.6% (95% CI: 47.3, 65.4) and 39.0% (95% CI: 32.7, 45.7), respectively [38]. However, another systematic review in developing countries showed that the average prevalence of occupation-related injuries among HCWs in their career and previous last year was 60.17%, ranging from 32% to 87.8% and 39.16%, ranging from 1.14% to 87%, respectively [3]. Our study indicates that the prevalence of occupational exposure to needlestick injury and mucocutaneous splashing reported for the previous year range from 27.1% to 59.2% is lower than what has been reported in other studies cited above, the differences in the sample size, study population scope, geographical differences, data collection, and statistical methods may explain this differences.

Additionally, we observed similar variability in the duration of exposure among the 5 studies that reported the prevalence of exposure to needlestick injury and those that reported the prevalence of exposure to mucocutaneous splashing; the majority (3, 60%) reported exposure in the past year, and two studies reported the entire career. The prevalence of needlestick injuries and mucocutaneous splashes in the past year varied from 20% to 71.7% and 21.7% to 56.7%, respectively [34, 36, 37]. A study in Somalia showed that 8.6% of healthcare workers sustained a needlestick and sharps injury incident in the past year, which is lower than our rate, probably due to differences in settings [39]. Our results are more comparable to those of Ethiopia, in which 30.6% (95% CI; 26.8–34.4) of healthcare workers had experienced needlestick and sharp injuries within their working area [40], and the pooled prevalence of needle-stick injuries in the past year was 28.8% (95% CI 23.0–34.5) [41]. Additionally, similar findings were reported in Ghana, in which 29.7% of respondents reported a needlestick accident during the previous year [42]. A study in developing countries indicated that the prevalence of needlestick injury ranged from 19.9% to 54.0%, with an overall prevalence of 35.7%, and that of needlestick injury ranged from 38.5 to 100%, with an overall prevalence of 64.1% in the previous year and throughout one’s career [43]; these findings are comparable to our findings. Previous studies on mucocutaneous splashing in Ethiopia (39.0% [44]), Ghana (53.7% [45]), Cameroon (86.7% [46]) and Kenya (25% [47]) have reported similar results.

Compliance with infection prevention and control in Tanzania is suboptimal, as reported by [48,49,50,51,52]. Additionally, knowledge, equipment and supplies and practices related to waste management were below the standards [53, 54]. Four studies in our review about exposure to hepatitis B virus showed that 87.3% of the healthcare workers were not adequately immunized [34]; approximately 89% of healthcare workers were not aware of their status and had never been vaccinated [55, 56], and the prevalence of chronic HBV infection among healthcare workers ranged from 5.7% to 7.0% [56, 57]. In this review, there were nine studies about HIV exposure risk, risk of HIV transmission mentioned were percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposure; inadequate knowledge; gender and work experience as described here below: The estimated risk of HIV transmission to healthcare workers due to needlestick injuries was calculated to be 7 cases per 1,000,000 HCW-years from one study [58], and another study showed that there was approximately 0.27% annual HIV risk for HCWs/year [59]. Five studies indicated low utilization rates of PEP (23.1%, 22.5%, 58%, 11.7% and 24%), and most of these studies found that knowledge and reporting were predictors of PEP use [35,36,37, 60, 61]. Four studies indicated that females had an increased risk of occupational exposure and were more knowledgeable about and likely to report and use safe precaution standards [34, 36, 60, 62]. Three studies reported that working experience is associated with an increased risk of occupational exposure [33, 56, 57], and two studies indicated more compliance with infection, prevention and control standards among health care workers with more work experience [49, 53]. Two other studies reported greater exposure to occupational injuries among less experienced healthcare workers [34, 63]. Healthcare workers who had knowledge on transmission and management of workplace HIV exposure were less likely to have poor practice of managing occupational exposure [32], supported by another study indicating healthcare workers not trained on the use of person protective equipment were less likely to have comprehensive knowledge on occupational exposure to HIV (OR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.9) [64].

To mitigate the risk of blood and body fluid occupational infections, various strategies, such as capacity building using specific training on occupational health and safety, PEP, infection prevention and control, vaccination for hepatitis B, supportive supervision, guidelines, the supply of PPE, the establishment of surveillance systems to monitor occupational exposures, the design of occupational health and safety personnel in hospitals, proper waste disposal, the placement of disaster preparedness tools in hospitals, the provision of information and instructions to all HCWs on actions to be taken in case of injury, the regulation of working hours to not more than 40 h per week and the recruitment of more staff, have been recommended [32,33,34,35,36,37, 60, 61, 63, 65].

In summary, stick needle injuries and mucocutaneous splashes are prevalent among healthcare workers in Tanzania, but strategies to protect healthcare workers are suboptimal.

5.2 Psychosocial hazards

Psychosocial factors are job satisfaction, service conditions, leadership, type of work, communication, payment, the welfare state, trade union activity, incentives, and others [66]. Health care workers are at increased risk of burnout due to the nature and environment of their job, which exposes them to high levels of emotional and psychological stress [67].

Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and Maslach et al. described it in three dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy [68]. Burnout is associated with absenteeism, high turnover rates, lack of motivation, and low work output [69,70,71]. Two studies included in this review reported a high prevalence of burnout (62%) [72] for different cadres of HCWs, and another study found that the prevalence of burnout was 67% for Tanzanian emergency service providers and 70% for specialists at Bugando Medical Hospital (70%) [73].

The work-related risk factors for burnout identified in this review were a longer duration of a single‐day shift, fewer night‐time sleeping hours, tobacco use and lack of regular exercise [72]. Other risks were dissatisfaction with career choice, consideration of switching institutions, working in an urban setting, inadequate coverage for emergencies/leaves, financial housing responsibilities, unnecessary administrative paperwork, working overnight shifts, pressure to achieve patient satisfaction or decrease length of stay, meaningful mentorship, and not having a close friend or having a family member dead [73]. Burnout risk is high in sections with higher workloads, such as emergency medicine, intensive care units and other high workload areas [74]; however, there are few studies conducted to provide solutions that will improve working conditions in these areas.

Workplace violence is any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site [75]. Workplace violence has been found to cause psychological distress, reduce work morale, and lead to low performance. One study reported that 71.79% of health workers were generally knowledgeable about gender-based violence; however, only 36.9% had good knowledge about gender-based violence management guidelines for gender-based violence [76]. In summary, psychosocial hazard is known to affect work performance despite limited related research.

5.3 Ergonomic hazards

Low back pain is an occupational injury that can be caused by poor posture, heavy lifting, repetitive movements, sitting for long periods, poorly designed workstations or equipment that does not support proper posture and alignment [77]. One of our studies reported that the prevalence of low back pain was 61.4%, and carrying the patient and standing for more than 3 h per day were the major contributors to low back pain [63].

In summary, work-related ergonomic hazards are increasing, while studies on work-related injuries among healthcare workers are rare.

5.4 Physical hazards

Workers may be exposed to physical hazards such as heat, noise, vibration, repetitive movement light and other radiations depending on the type of work [78]. A slippery floor increases the risk of sliding, slipping, riding, and falling whereby a person rests inadvertently on the ground or floor or at other lower levels, which can result in injuries ranging from minor bruises to severe fracture or head injuries [79]. Floor slippage can be caused by various factors, such as spills, wet surfaces, wax or polish residue, or even improperly floating materials [80]. In our case, one study reported that the incidence of slippery floors was 5.9% [65] among other occupational exposures, this is supported by the published report on work related injuries in Tanzania, indicating an increasing trend in both fatal and nonfatal work-related injuries reported to workers’ compensation funds from 2016 to 2019, and motor traffic accidents, machine faults and falls were the most reported causes of musculoskeletal disorders [81].The medical sector contributes approximately 98% of the population’s radiation dose from all human-made sources [82]. Prolonged or high-level exposure to ionizing radiation can have adverse health effects, including increased risk of cancer, cataracts, skin burns, radiation sickness, and genetic mutations [83]. One study in this review reported that most staff members had low to moderate knowledge of radiation safety [62]. Workers in the radiology department are required to be monitored for radiation exposure levels using dosimeters [84].

In summary, physical hazard is an occupational alarming concern in Tanzania, healthcare workers’ knowledge of safety is limited, and research in this field is limited.

5.5 Chemical hazards

One study in this review examined chemical hazard exposure to antiseptics and disinfectants, which resulted in chemical burns with a 10.6% prevalence of exposure [65]. Other studies have shown that chemicals such as chlorhexidine, natural rubber latex and ortho‐phthalaldehyde contribute to allergic airway inflammation; the prevalence of asthma ranges from 7 to 10% among healthcare workers in hospital settings [85, 86]. The use of less allergenic alternatives, such as powder-free latex gloves and nitrile gloves, has been recommended for controlling latex exposure among healthcare workers [87], and less allergenic disinfectants, such as buffered peracetic acid-based products, can be used as alternatives [88] while meeting safety precautions and standards to limit exposure [89]. In summary, this area has not been well researched to explore the magnitude of the problem and address the key challenges.

6 Implications

This scoping review revealed that healthcare workers in Tanzania are exposed to a wide range of occupational hazards and that risk reduction strategies and safety measures are inadequately implemented, mainly due to equipment and human resource limitations. To protect healthcare workers in Tanzania, occupational health and safety first and foremost need to be prioritized. This requires political commitment from the government to increase investments in occupational health and safety programs and create a comprehensive national strategy for OHS specifically tailored to the needs of healthcare workers, informed by the evidence based data. In line with this, the implementation of occupational health and safety requires regularly review and update legislation and policies related to OHS to reflect changes in healthcare practices, new research findings, and lessons learned from implemented programs.

7 Strengths and limitations of the review

To our knowledge, this review on exposure to occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania is the most comprehensive to date. This study was based on a rigorous, systematic search strategy across four large databases with no date restrictions using strict methodological inclusion criteria. Our findings might differ from those of other countries due to differences in regulatory frameworks; health infrastructure; and socioeconomic, cultural, and policy factors. Additionally, within the healthcare context, there are likely considerable differences between occupations in terms of the hazards faced (nurses versus doctors; versus support personnel). Thus, the overall findings for Tanzania healthcare workers might not be as useful as differentiating between occupations.

Although this review provides an overall synopsis of occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania, there are several limitations to this study. First, the quality of the included studies was not assessed, which could have limited our findings; therefore, the review was inclusive of all the articles, irrespective of their quality. Second, only articles published in English were included, which might have resulted in the exclusion of data published in other languages. Third, all the data may not have been captured by the search strategy, particularly if the articles were published in journals not indexed in Medline, Scopus, Web of Science or Science Direct. Despite these limitations, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the hazards encountered in the workplace by healthcare workers in Tanzania.

We propose a solution for occupational hazards in Tanzania using a High-Reliability Organization (HRO) model which is particularly relevant for health facilities with potential hazards, complex environments and involving multiple professionals, technologies, and procedures [90]. The HRO model components as shown in Fig. 7; 1. Sensitivity to Operations: HROs pay close attention to the details of their operations, which in healthcare means being vigilant about the procedures, protocols, and daily practices that could impact patient and worker’s safety; 2. Reluctance to Simplify Interpretations: HROs avoid oversimplifying complex situations. In healthcare, this means recognizing the complexity of medical work and not reducing safety to a single cause or solution; 3. Preoccupation with Failure: HROs are characterized by a constant focus on the possibility of failure and how to prevent it. This involves continuous risk assessment and learning from near misses and past incidents; 4. Commitment to Resilience: HROs build in redundancy and buffers to handle failures. In healthcare, this could mean having backup systems, cross-trained staff, and contingency plans; 5. Deference to Expertise: HROs ensure that decisions are made by those with the most relevant expertise in a healthcare setting, this supports evidence-based practices and trusting the judgment of frontline workers; 6. The concept of "mindfulness of operations" as one of the key characteristics of High-Reliability Organizations (HROs) was introduced by Karl Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe in their work on managing the unexpected in organizations. Mindfulness of Operations maintain a heightened state of awareness and mindfulness regarding ongoing operations and potential risks [91].

In summary, the HRO model is well-suited for addressing occupational health and safety hazards for the Tanzanian context due to its focus on maintaining high levels of safety and reliability in the face of potential hazards. It encourages a culture of continuous learning, vigilance, and adaptability, which are critical for managing occupational hazards among healthcare workers.

8 Conclusions

A large proportion of healthcare workers in Tanzania are occupationally exposed to a wide range of hazards. Safety measures and risk reduction strategies in Tanzania are suboptimal, mainly due to resource limitations. Healthcare workers must be protected from occupational hazards as this can adversely impact the quality of care provided. In addition, the majority of the studies involved biological hazards, indicating high exposure to pathogens, coinciding with inadequate protective measures and low knowledge among healthcare workers. Moreover, it was found that majority of the healthcare workers were not aware of and not vaccinated against hepatitis B, and had low HIV PEP uptake. Furthermore, compliance with infection prevention and control in Tanzania was reported below the standard, while the production of medical waste is tremendously increasing following high investment in the health sector.

This research found that the research on occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania has increased considerably in the last decade. However, most of the articles focused on biological hazards indicating the need for further research in this area.

9 Recommendations

The following are key recommendations for improvement of occupational health and safety in Tanzania:

The government should prioritize the revision and enforcement of occupational health and safety (OHS) policies to ensure they are comprehensive and up-to-date with international standards.

Allocate sufficient resources for the healthcare service delivery and implementation of OHS measures in healthcare facilities, including the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE), training, staffs and infrastructure improvements.

Implement regular training programs for healthcare workers on OHS, infection prevention and control, and the proper use of PPE. Include modules on biological, psychosocial, ergonomics, physical, chemical hazards.

Develop a robust system for monitoring and reporting occupational exposures and injuries to facilitate timely interventions and continuous improvement of safety measures.

Engage with local communities and the public to raise awareness about the importance of OHS for healthcare workers and the impact on quality of patient care and collaborate with international organizations, non-governmental organizations, and academic institutions to share best practices and develop joint strategies for OHS in healthcare.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Boniol MKT, Nair TS, Siyam A, Campbell J, Diallo K. The global health workforce stock and distribution in 2020 and 2030: a threat to equity and “universal” health coverage? BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:6.

Collaborators GH. Measuring the availability of human resources for health and its relationship to universal health coverage for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2129–54.

Debelu D, Tolera ST, Aschalew A, Deriba W. Occupational-related injuries and associated risk factors among healthcare workers working in developing countries: a systematic review. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2023;10:23333928231192830.

Takala J, Sauni R, Nygård CH, Gagliardi D, Neupane S. Global-, regional- and country-level estimates of the work-related burden of diseases and accidents in 2019. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2024;50(2):73–82.

APHA. Occupational Health and Safety. 2024 [cited 2024 18/05]; https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/occupational-health-and-safety.

Liu J, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, Yan S, Sampson O, Xu H, Wang C, Zhu Y, Chang Y, Yang Y, Yang T, Chen Y, Song F, Lu Z. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–37.

Rezaei B, Heshmati B, Asadi S. Low back pain and its related risk factors in health care providers at hospitals: a systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;70:102903.

Acke S, Bramer WM, Schmickler MN, De Schryver A, Haagsma JA. Global infectious disease risks associated with occupational exposure among non-healthcare workers: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med. 2022;79(1):63–71.

Shabani T, Steven J, Shabani T. Significant occupational hazards faced by healthcare workers in Zimbabwe. Life Cycle Reliability Safety Eng. 2024;13(1):61–73.

Tomaszewska K, et al. Stress and occupational burnout of nurses working with COVID-19 Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:19.

Tawiah PA, Effah ES, Adu-Fosu G, Ashinyo ME, Alhassan RK, Appiah-Brempong E, Afriyie-Gyawu E. Occupational health hazards among healthcare providers and ancillary staff in Ghana: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10):e064499.

WHO. Global action on patient safety. in Seventh plenary meeting, 28 May 2019 A72/VR/7. 2019. Geneva.

Rai R, Dorji N, Rai BD, Fritschi L. Exposure to occupational hazards among health care workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5.

Nathan Ezie K, Scott GY, Andigema AS, Musa SS, Takoutsing BD, Lucero-Prisno Iii DE. Healthcare Workers’ Safety; A Necessity for a Robust Health System. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):57.

Jullien S. Wasting resources in health care - unnecessary hospitalisations and over-medicalisation: The health workers’ or the health systems’ fault? Evidence from Romania and Tajikistan and implications for global health. J Glob Health. 2023;13:03018.

JM, A., The Value of Worker Well-Being. Public Health Rep, 2019. 134(6): 583–586.

Ministry of Labour, E.a.Y.D., National Occupational Health and Safety Policy. 2009.

Tanzania, G.o., Occupational Safety and Health Act P.o.t.U.R.o. Tanzania, Editor. 2003.

Tolera ST, T.S., Mulat Endalew S, Alamirew TS, Temesgen LM, Global systematic review of occupational health and safety outcomes among sanitation and hygiene workers. Front Public Health, 2023. 11: 1304977.

Tanzania, G.o., Ripoti_ya_Mgawanyo_wa_Idadi_ya_watu_kwa_Umri_na_Jinsi_Tanzania_Matokeo_Muhimu, N.B.o. Statistics, Editor. 2022: Dodoma.

Health, M.o., TANZANIA MINISTER OF HEALTH BUDGETARY SPEECH BY HON. UMMY ALLY MWALIMU (MP), INCOME AND EXPENDITURE PLANS FOR 2024/2025. 2024.

Health, M.o. Health Facility Registry. 2024 [cited 2024 11/March]; Available from: https://hfrs.moh.go.tz/web/index.php.

USAID. Tanzania HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2023.

Kilonzo SB, et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection in Tanzania: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Med. 2024;2024:1.

NTLP. TB Prevalence in Tanzania. 2024 [cited 2024 10/March]; https://ntlp.go.tz/tuberculosis/tb-prevalence-in-tanzania/.

Levac D, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Colquhoun HL, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, Kastner M, Moher D. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Santos WM, Secoli SR. The Joanna Briggs Institute approach for systematic reviews. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2018;26:1.

Icco AC, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

WHO Classifying Health workers. 2019.

Mossburg S, Nkimbeng M, Commodore-Mensah Y. Occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Africa: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85:1.

Mashoto KO, et al. Self-reported occupational exposure to HIV and factors influencing its management practice: a study of healthcare workers in Tumbi and Dodoma Hospitals Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:276.

Laisser RM, Ng’home JF. Reported incidences and factors associated with percutaneous injuries and splash exposures among healthcare workers in Kahama District Tanzania. Tanzania J Health Res. 2017;19:1.

Chalya PL, Mushi MF, Mirambo MM, Jaka H, Rambau PF, Mabula JB, Kapesa A, Ngallaba SE, Massinde AN, Kalluvya SE. Needle-stick injuries and splash exposures among health-care workers at a tertiary care hospital in north-western Tanzania. Tanzania J Health Res. 2015;17:2.

Kimaro L, et al. Prevalence of occupational injuries and knowledge of availability and utilization of post exposure prophylaxis among health care workers in Singida District Council, Singida Region, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10): e0201695.

Mponela MJ, et al. Post exposure prophylaxis following occupational exposure to HIV: a survey of health care workers in Mbeya, Tanzania, 2009–2010. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:32.

Mabwe P, Kessy AT, Semali I. Understanding the magnitude of occupational exposure to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and uptake of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare workers in a rural district in Tanzania. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96(3):276–80.

Mengistu DA, D.G.,. Global occupational exposure to blood and body fluids among healthcare workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2022;2022:5732046.

Mohamud RYH, Doğan A, Hilowle FM, Isse SA, Hassan MY, Hilowle IA. Needlestick and Sharps Injuries Among Healthcare Workers at a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023;16:2281–9.

Tsegaye Amlak B, Tesfamichael B, Abebe H, Zewudie BT, Mewahegn AA, Chekole Temere B, Terefe TF, GebreEyesus FA, Tsehay T, Solomon M. Needlestick and sharp injuries and its associated factors among healthcare workers in Southern Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121221149536.

Yazie TD, Tebeje MG. Prevalence of needlestick injury among healthcare workers in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019;24(1):52.

Appiagyei H, Donkor P, Mock C. Occupational injuries among health care workers at a public hospital in Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:103.

Mengistu DA. Prevalence of occupational exposure to needle-stick injury and associated factors among healthcare workers of developing countries: systematic review. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1): e12179.

Yasin J, Mekonnen F, Yirdaw K. Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids and associated factors among health care workers at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019;24(1):18.

Tawiah PA, Okyere P, Ashinyo ME. Splash of body fluids among healthcare support staff in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241234470.

Takougang I, Ze BRS, Tsamoh FF, Moneboulou HM. Awareness of standard precautions, circumstances of occurrence and management of occupational exposures to body fluids among healthcare workers in a regional level referral hospital (Bertoua, Cameroon). BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):424.

Mbaisi EM, Wanzala P, Omolo J. Prevalence and factors associated with percutaneous injuries and splash exposures among health-care workers in a provincial hospital, Kenya, 2010. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:10.

Powell-Jackson T, et al. Infection prevention and control compliance in Tanzanian outpatient facilities: a cross-sectional study with implications for the control of COVID-19. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e780–9.

Bahegwa RP, et al. Factors affecting compliance with infection prevention and control standard precautions among healthcare workers in Songwe region, Tanzania. Infect Prev Pract. 2022;4(4): 100236.

R, B.S.A., Preparedness of health facilities providing HIV services during COVID-19 pandemic and assessment of their compliance to COVID-19 prevention measures: findings from the Tanzania Service Provision Assessment (SPA) survey. Pan Afr Med J, 2020.

Rayson D, et al. Comparison of hand hygiene compliance self-assessment and microbiological hand contamination among healthcare workers in Mwanza region, Tanzania. Infect Prev Pract. 2021;3(4): 100181.

Hokororo J, Ngowi R, German RC, Bahegwa R, Msigwa Y, Nassoro O, Marandu L, Kiremeji M, Lutkam D, Habtu M, Lusaya E, Eliakimu E. Evaluation of Infection Prevention and Control Compliance in Six Referral Hospitals in Tanzania using National and World Health Organization Standard Checklists. Prev Med Epidemiol Public Health. 2021;2(3):2–9.

Millanzi WC, Herman PZ, Mtangi SA. Knowledge, attitude, and perceived practice of sanitary workers on healthcare waste management: a descriptive cross-sectional study in Dodoma region Tanzania. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231174736.

Nilsson J, Urasa M, Darj E. Safe injections and waste management among healthcare workers at a regional hospital in northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2013;15(1):64–70.

Debes JD, Kayandabila J, Pogemiller H. Knowledge of Hepatitis B Transmission Risks Among Health Workers in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(5):1100–2.

Shao ER, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among healthcare workers in northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):474.

Mueller A, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:386.

Mashoto KO, Makundi E, Mohamed H, Malebo HM. Estimated risk of HIV acquisition and practice for preventing occupational exposure: a study of healthcare workers at Tumbi and Dodoma Hospitals Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:369.

Gumodoka B, Berege ZA, Dolmans WMV. Occupational exposure to the risk of HIV infection among health care workers in Mwanza Region, United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(2):133–40.

Lahuerta M, et al. Reporting and case management of occupational exposures to blood-borne pathogens among healthcare workers in three healthcare facilities in Tanzania. J Infect Prev. 2016;17(4):153–60.

Chagani MM. Healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on post exposure prophylaxis for HIV in Dar es salaam. Tanz Med J. 2011;25(2011):2.

Sakafu L, et al. Radiation safety in an era of diagnostic radiology growth in Africa: Lessons learned from Tanzania. Clin Imaging. 2023;102:65–70.

Mligiliche NL, Masinga J, Ntigga FB, Mtoro S. Prevalence and Predictors of Occupational Health Hazards among Nurses Working in Health Care Facilities at Moshi Municipal, Kilimanjaro. Tanzania TMJ. 2022;33:1.

Mashoto KO, Mubyazi GM, Mushi AK. Knowledge of occupational exposure to HIV: a cross sectional study of healthcare workers in Tumbi and Dodoma hospitals. Tanzania BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:29.

Manyele SV. The status of occupational safety among health service providers in hospitals in Tanzania. Tan J Health Res. 2008;10:3.

Zhen Y. Occupational Hazards. In: Quanjun L, editor. Preventive Medicine. London, UK: International Clinical Medicine Series Based on the Belt and Road Initiatives; 2020. p. 241–2.

Soares JP, Mendonça PBS, Silva CRDV, Rodrigues CCFM, Castro JL. Use of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Among Public Health Care Professionals: Scoping Review. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:e44195.

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

Lee C, Fuller JA, Freedman M, Bannon J, Wilkins JT, Moskowitz JT, Hirschhorn LR, Wallia A, Evans CT. The association of burnout with work absenteeism and the frequency of thoughts in leaving their job in a cohort of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Health Serv. 2023;3:1.

S, D.H., Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local Reg Anesth, 2020. 13: 171–183.

Kelly LA. Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69(1):96–102.

Lwiza AF, Lugazia ER. Burnout and associated factors among healthcare workers in acute care settings at a tertiary teaching hospital in Tanzania: an analytical cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(5): e1256.

Iyer S, S.S., Qiu Y, Platt S, Risk factors for physician burnout: a perspective from Tanzania. 2022.

Klick JC, et al. Health and well-being of intensive care unit physicians: how to ensure the longevity of a critical specialty. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(1):303–16.

USDOL. Safety and Health Topics - Workplace Violence. 2024 [cited 2024 13/04]; Available from: https://www.osha.gov/workplace-violence.

Mtaita C, et al. Knowledge, Implementation, and Gaps of Gender-Based Violence Management Guidelines among Health Care Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:7.

Karahan A, Abbasoglu A, Dogan N. Low back pain: prevalence and associated risk factors among hospital staff. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(3):516–24.

Zhen, Y., Physical hazards, in Preventive Medicine, L. Quanjun, Editor. 2020. p. 239–240.

de Souza AB, Maestri RN, Mutlaq MFP, Lorenzini E, Alves BM, Oliveira D, Gatto DC. In hospital falls of a large hospital. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):284.

Drebit S, Alamgir H, Yu S, Keen D. Occupational and environmental risk factors for falls among workers in the healthcare sector. Ergonomics. 2010;53(4):525–36.

Shewiyo BS, et al. Work-Related Injuries Reported toWorkers Compensation Fund in Tanzania from 2016 to 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:17.

S., J., Radiation in medical practice & health effects of radiation: Rationale, risks, and rewards. J Family Med Prim Care, 2021. 10(4): 1520–1524.

WHO. Ionizing radiation and health effects. fact sheet 2023 [cited 2024 13th April].

Akram S, Radiation Exposure Of Medical Imaging. 2022, StatPearls [Internet]: Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Mwanga HH, Singh T, Jeebhay MF. Work-related allergy and asthma associated with cleaning agents in health workers in Southern African tertiary hospitals. Am J Ind Med. 2022;65(5):382–95.

Mwanga HH, Singh T, Jeebhay MF. Asthma Phenotypes and Host Risk Factors Associated With Various Asthma-Related Outcomes in Health Workers. Front Allergy. 2021;2:747566.

Naranje N, Parate KP, Reche A. Comparative assessment of hypersensitivity reactions on use of latex and nitrile gloves among general dental practitioners: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e46443.

Otterspoor S. An evaluation of buffered peracetic acid as an alternative to chlorine and hydrogen peroxide based disinfectants. Infect Dis Health. 2019;24(4):240–3.

Gharpure R, Hunter CM, Schnall AH. Safe use and storage of cleaners, disinfectants, and hand sanitizers: knowledge, attitudes, and practices among U.S. Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic, May 2020. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104(2):496–501.

Veazie S, et al. Implementing high-reliability organization principles into practice: a rapid evidence review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):e320–8.

Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the librarians from Southern Medical University for their support in searching for the literatures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DML developed the search strategy; screened, extracted and analyzed the data; and prepared the manuscript. SSK and JM contributed to the development of the search strategy, screening and extracting the data and editing the manuscript and WY contributed to the manuscript revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lyakurwa, D.M., Khalfan, S.S., Mugisha, J. et al. Occupational hazards among healthcare workers in Tanzania: a scoping review. Discov Public Health 21, 32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00160-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00160-7