Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence is a primary determinant of sustained viral suppression, HIV transmission risk, disease progression and death. The World Health Organization recommends that adherence support interventions be provided to people on ART, but implementation is suboptimal. We evaluated linkage to intensive adherence counselling (IAC) for persons on ART with detectable viral load (VL).

Methods

Between January and December 2017, we conducted a retrospective chart review of HIV-positive persons on ART with detectable VL (> 1000 copies/ml), in Gomba district, rural Uganda. We abstracted records from eight HIV clinics; seven health center III’s (facilities which provide basic preventive and curative care and are headed by clinical officers) and a health center IV (mini-hospital headed by a medical doctor). Linkage to IAC was defined as provision of IAC to ART clients with detectable VL within three months of receipt of results at the health facility. Descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate factors associated with linkage to IAC.

Results

Of 4,100 HIV-positive persons on ART for at least 6 months, 411 (10%) had detectable VL. The median age was 32 years (interquartile range [IQR] 13–43) and 52% were female. The median duration on ART was 3.2 years (IQR 1.8–4.8). A total of 311 ART clients (81%) were linked to IAC. Receipt of ART at a Health Center level IV was associated with a two-fold higher odds of IAC linkage compared with Health Center level III (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.78; 95% CI 1.00–3.16; p = 0.01). Age, gender, marital status and ART duration were not related to IAC linkage.

Conclusions

Linkage to IAC was high among persons with detectable VL in rural Uganda, with greater odds of linkage at a higher-level health facility. Strategies to optimize IAC linkage at lower-level health facilities for persons with suboptimal ART adherence are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence is a modifiable determinant of viral suppression and long-term treatment success i.e., viral load (VL) suppression below the lower limit of detection of commercially available assays [1,2,3,4]. Persons with suboptimal ART adherence have sub-therapeutic drug levels and are three times as likely to rapidly progress to virologic failure compared with those who adhere to ART [5, 6]. Barriers to ART adherence include number and timing of doses, pill size, side-effects, transportation costs to the HIV clinic, depression and substance abuse [7]. Targeted adherence interventions, including adherence counselling, improve viral suppression in 57–84% of individuals with detectable viraemia [8,9,10]. Failure to achieve viral suppression after adherence counseling is assumed to indicate virologic failure in settings where drug resistance testing is unavailable [11]. Studies suggest that approximately 70% of persons on first-line ART who have a first high viral load will re-suppress following an adherence intervention [8], suggesting that non-adherence is a key reason for unsuppressed viral load.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that HIV-positive persons with detectable VL (> 1000 copies/ml), be offered enhanced adherence counselling [12]. In 2016, the government of Uganda implemented intensive adherence counseling (IAC) for persons with detectable HIV viral load in accordance with WHO recommendations [13]. The goal of IAC is to help clients identify and gain insight into their specific adherence barriers, explore strategies to overcome these barriers and to formulate a comprehensive adherence plan to help improve ART adherence [12, 14]. An IAC multidisciplinary team comprises of counsellors, clinicians, family members, nurses, peers, nutritionists and psychiatrists who address multi-factorial issues that influence adherence including nutrition, stigma and disclosure [12, 13]. The IAC package includes the provision of individual needs assessment, education sessions and adherence counselling to patients and the use of 5As—Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist and Arrange–when offering adherence support to people with detectable viraemia [13].

For all those with detectable VL, Uganda guidelines recommend 3 IAC sessions, 1 month apart, with repeat viral load testing one month after the 3rd IAC session [15]. Those with persistent virologic failure after IAC are considered for switching to second line treatment provided that all adherence challenges have been addressed [15]. Since its launch in Uganda in 2016, implementation of IAC has been suboptimal. An analysis of 449 children and adolescents with detectable VL (> 1,000 copies/ml) found that 77% completed all 3 IAC sessions, 16% received one or two sessions and 7% were not linked to IAC within 400 days of receiving a viral load result [16]. Little is known about linkage to IAC for adults in sub-Saharan Africa and in rural settings. Suboptimal adherence is a major challenge globally because of a diversity of person- and facility-level factors. Characterizing factors affecting IAC implementation will help improve HIV service delivery. The objective of this study was to evaluate IAC linkage among HIV-positive persons on ART with detectable viral loads in Gomba District, Uganda.

Materials and methods

Subjects and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of HIV-positive persons who received ART between January and December 2017 at 8 HIV clinics in Gomba district, rural Uganda [17]. Gomba, one of 136 administrative districts in Uganda, has a population of 160,075 of which 92% is rural and 49% are female [18]. Uganda’s healthcare system operates on a referral system, in which lower-level facilities refer cases to the next level unit. Primary care facilities are organized by administrative division and include Health Center II (parish), Health Center III (sub-county) and Health Center IV (county). Gomba district had one Health Center IV (a mini hospital with surgical and obstetric services managed by a medical doctor) and 7 Health Center III facilities (each with a general outpatient clinic and maternity ward and led by clinical officers) [19]. In 2016, Uganda adopted WHO recommendations to offer immediate ART to all persons newly diagnosed with HIV [13]. Following ART initiation, VL testing is performed after 6 months, and if virally suppressed, 12 months thereafter [13]. At scheduled clinic visits, socio-demographic and clinical data are recorded on client treatment cards (blue card) and clients are asked to return to clinic every three months for adherence assessment and ART refills. At the scheduled visit for VL testing, the date of blood sample collection is documented on the client’s blue card. Samples from the 8 ART clinics are warehoused at a district laboratory hub prior to transportation to the national reference laboratory. Facility staff document VL results in viral load registers and on client blue cards at subsequent clinic visits [17].

Population and procedures

Clients with detectable VL received IAC every month and a minimum of three IAC sessions were required prior to repeat viral load testing which was performed at the third IAC visit [17]. At the health center IV, counselling was provided by health care workers including adherence counsellors, nurses and clinical officers. At the health center III, IAC provision was supported by peers (expert clients with HIV or members of village health teams) due to limitations in the numbers of health workers. Peers were trained and supervised by health workers during provision of IAC. Data were collected from all 8 ART clinics during a 6-week period from mid-October to November 2018. We included all clients with detectable VL at all eight health facilities. Each client was given a unique identifier and data abstracted from viral load registers, IAC registers and client treatment cards that contain a record of client details. These documents were completed at each clinic visit by the health facility staff. Data on age, sex, marital status, duration on ART, and dates of viral load testing, receipt of test results and first IAC session, the number of IAC sessions and health facility level were entered into a Microsoft® Excel database. Quality control checks were performed to ensure data quality.

Laboratory methods

Viral load testing was performed in batch at the Central Public Health Laboratory as standard of care using the COBAS® AmpliPrEP/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, v2.0 kit (Roche Molecular System, Inc, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Viral load test results were returned to ART clinics within 6–8 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Linkage to IAC (the primary outcome) was defined as provision of IAC to an HIV-positive person with detectable VL within three months of receipt of VL viral load results at the health facility. Detectable VL was defined as HIV RNA concentration > 1,000 copies/ml [11]. Time to first IAC session was was counted from the date of receipt of VL test results at the health facility to date of first IAC session. We used descriptive analytical methods and a multivariable logistic regression model to assess factors related to lAC linkage. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to test relationships between categorical variables. Factors with p ≤ 0.2 in bivariate analyses were included in the multivariable model. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM, Corp. Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the University of Liverpool Board of Ethics (H00057734), Mildmay Uganda Research Ethics Committee (0208–2018) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS255ES). Administrative clearance was obtained from the District Health Officer of Gomba district prior to study implementation.

Results

Participant characteristics

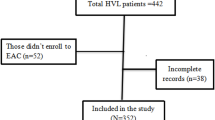

A total of 4,100 clients had received ART for at least six months during the study period. Of these, 411 (10%) had detectable VL (> 1000 copies/mL) and were included in the retrospective analysis. The median age was 32 years (interquartile range [IQR] 13–43) and 52% were female (Table 1). The median duration on ART was 3.2 years (IQR 1.8–4.8), and most (63%) received ART services at a Health Center level III facility.

Linkage to IAC

Three hundred and thirty one participants (81%) with non-suppressed viraemia were linked to the IAC intervention within three months of receipt of viral load test results. Sixteen percent (65/411) had not been linked to IAC by the time of the study, and three percent (15/411) had been linked to IAC after more than three months. Nearly all widowed participants (96%) were linked to IAC. Linkage was similar among participants who had been on ART for more than 5 years and those on ART for 6–11.9 months (89% vs. 76%; p = 0.07). A higher proportion of participants receiving HIV care at Health Center IV were linked to IAC than Health Center III ART recipients (87% vs 77%; p = 0.01). Similar proportions of women and men (82% and 79%, respectively) were linked to IAC.

In bivariate analysis, clients receiving ART at Health Center IV facilities had two-fold higher odds of linkage to IAC compared with Health Center III (odds ratio [OR] 2.04 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18–3.54; p = 0.01) (Table 1). There was a non-statistically significant trend for IAC linkage among those with ART duration > 5 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.54; 95% CI 0.94–6.83; p = 0.07). In multivariable analyses, receipt of ART at a Health Center level IV was significantly associated with linkage to IAC (adjusted OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.00–3.16; p = 0.01). Age, gender, marital status and ART duration were not related to IAC linkage.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 4,100 HIV-positive women and men in rural Uganda, one-in-ten had detectable viral load. Eighty one percent were linked to the IAC intervention within 3 months of receipt of viral load results at the HIV care facility. Receipt of HIV treatment at a higher level public health facility was the only factor associated with linkage to IAC. Linkage was similar with respect to age, gender, marital status and duration of ART.

We found that persons receiving HIV care at a Health Center IV had two-fold higher odds of linkage to IAC compared to Health Center III, perhaps because Health Center IV staff conducted IAC themselves whereas patients at Health Center III facilities were referred to peer counsellors [17]. This extra step in linkage to IAC may have increased the odds of non-linkage. Additionally, peer counsellors were sometimes unavailable due to other health system support roles they performed in the community. Improving linkage to IAC at lower-level health facilities is needed to improve HIV treatment outcomes in Uganda. Prompt linkage to IAC and routine VL monitoring to confirm treatment response facilitates faster regimen switch to second line ART in a setting where genotypic testing to inform choice of efficacious drugs is not standard of care because of high cost [20,21,22]. We found that gender was not associated with linkage to IAC. Similar findings have been reported from South Africa where gender was not associated with uptake of HIV treatment [23].

IAC is also known as enhanced adherence counselling (EAC) elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa where it is standard of care for patients failing first- or second-line ART. A study in Uganda found that IAC was ineffective, with 91% of persons on first-line ART remaining virologically unsuppressed (VL > 1000 copies/ml) after 3 months [24]. In contrast, a study in South Africa found that enhanced adherence counselling was effective for patients unsuppressed on second-line ART [25]. In this study, in which 64% were resuppressed after 3 months, EAC consisted of at least one counseling session with an experienced adherence counsellor or social worker and follow up visits with a medical officer experienced in treatment failure until they re-suppressed. Similar findings were observed in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Mali and Senegal, in West Africa, where 67% of patients re-suppressed on second line ART after 4 months [26] In this study, IAC consisted of monthly counselling sessions coupled with any of the following strategies: directly observed therapy by a pill buddy, a pill organizer, weekly phone calls, daily alarm reminders, daily text messages, home visits, or peer self-help groups. IAC curricula and implementation strategies vary among countries and health systems in sub-Saharan Africa and may account for these divergent results [27].

The proportion linked to IAC in our study is similar to other work in sub-Saharan Africa. In an evaluation of 489 people with plasma viral loads > 1,000 copies/ml in Zimbabwe, 83% attended all three enhanced adherence counselling sessions, and 47% re-suppressed [28]. Although we did not evaluate viral suppression as a measure of the effectiveness of IAC, attendance of all 3 adherence sessions in the Zimbabwean study was independently associated with higher probability of viral suppression. In the ADVANCE trial in South Africa, in which viral suppression with dolutegravir plus either tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disproxil fumarate was non-inferior to standard of care, adherence counseling led to resuppression of viraemia [29]. Two studies in South Africa found that following IAC, viral re-suppression occurred in 68% and 61% of persons on ART, respectively [25, 30]. A study in rural Uganda found that 60% of HIV-positive persons with detectable viraemia achieved viral suppression after adherence counselling interventions [31]. These findings suggest that most treatment failure in this setting is associated with non-adherence and can be addressed with targeted adherence support [32].

The strengths of our study include the district-wide assessment of linkage to IAC in a rural setting, and the large sample size with similar proportions of women and men which improves the generalizability of our findings. Our study has limitations. We did not conduct viral load or drug resistance testing after IAC and are unable to assess the effectiveness of IAC in this setting. However, drug resistance testing is not routinely available. Finally, we did not evaluate counseling quality or fidelity to IAC counseling materials in this programmatic setting.

In conclusion, linkage to IAC was high among persons with detectable viral load in rural Uganda. Receiving services from Health Center level IV was associated with increased odds of linkage to IAC.Strategies to optimize IAC linkage at lower-level health facilities for persons with suboptimal ART adherence are needed. Future studies should or conduct qualitative research to explore participant and provider perceptions and experiences with IAC and generate actionable data for program improvement.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- IAC:

-

Intensified adherence counselling

- ART:

-

Anti-retroviral treatment

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- VL:

-

Viral load

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, Moss A. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–3.

Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(8):564–73.

Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4+ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 x 10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):810–6.

Hughes MD, Johnson VA, Hirsch MS, Bremer JW, Elbeik T, Erice A, Kuritzkes DR, Scott WA, Spector SA, Basgoz N, et al. Monitoring plasma HIV-1 RNA levels in addition to CD4+ lymphocyte count improves assessment of antiretroviral therapeutic response. ACTG 241 Protocol Virology Substudy Team. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(12):929–38.

Bezabhe WM, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and virologic failure: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2016, 95(15).

Bulage L, Ssewanyana I, Nankabirwa V, Nsubuga F, Kihembo C, Pande G, Ario AR, Matovu JK, Wanyenze RK, Kiyaga C. Factors Associated with virological non-suppression among HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda, August 2014-July 2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):326.

Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, Orrell C, Altice FL, Bangsberg DR, Bartlett JG, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817-833(W284-W294).

Bonner K, Mezochow A, Roberts T, Ford N, Cohn J. Viral load monitoring as a tool to reinforce adherence: a systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(1):74–8.

Jobanputra K, Parker LA, Azih C, Okello V, Maphalala G, Kershberger B, Khogali M, Lujan J, Antierens A, Teck R. Factors associated with virological failure and suppression after enhanced adherence counselling, in children, adolescents and adults on antiretroviral therapy for HIV in Swaziland. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0116144.

G Diress, S Dagne, B Alemnew, S Adane, Addisu A. Viral load suppression after enhanced adherence counseling and its predictors among high viral load HIV seropositive people in north wollo zone public hospitals, northeast Ethiopia, 2019 retrospective cohort study AIDS research and treatment 2020 2020

WHO: What's new in treatment monitoring: viral load and CD4 testing. In: Update July. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

WHO: Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach: World Health Organization; 2016.

MOH: Consolidated Guidelines on the Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda. In. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2018.

Ministry of Health. Uganda Clinical Guidelines. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health. In; 2016.

Ministry of Health: Consolidated Guidelines on the Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda. In. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2018.

Nasuuna E, Kigozi J, Babirye L, Muganzi A, Sewankambo NK, Nakanjako D. Low HIV viral suppression rates following the intensive adherence counseling (IAC) program for children and adolescents with viral failure in public health facilities in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1048.

District Health Officer Gomba: Annual District Health sector Performance Report. 2018.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics: The national population and housing census 2014-main report. Kampala: Uganda; 2016. . In.; 2016.

Orem JN, Zikusooka CM. Health financing reform in Uganda: How equitable is the proposed National Health Insurance scheme? Int J Equity Health. 2010;9(1):23.

Omooja J, Nannyonjo M, Sanyu G, Nabirye SE, Nassolo F, Lunkuse S, Kapaata A, Segujja F, Kateete DP, Ssebaggala E, et al. Rates of HIV-1 virological suppression and patterns of acquired drug resistance among fisherfolk on first-line antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(10):3021–9.

Nicholas S, Poulet E, Wolters L, Wapling J, Rakesh A, Amoros I, Szumilin E, Gueguen M, Schramm B. Point-of-care viral load monitoring: outcomes from a decentralized HIV programme in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(8):e25387.

Phillips A, Cambiano V, Nakagawa F, Magubu T, Miners A, Ford D, Pillay D, De Luca A, Lundgren J, Revill P. Cost-effectiveness of HIV drug resistance testing to inform switching to second line antiretroviral therapy in low income settings. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109148.

Meehan S-A, Sloot R, Draper HR, Naidoo P, Burger R, Beyers N. Factors associated with linkage to HIV care and TB treatment at community-based HIV testing services in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195208.

Birungi J, Cui Z, Okoboi S, Kapaata A, Munderi P, Mukajjanga C, Nanfuka M, Nyonyintono M, Kim J, Zhu J. Lack of effectiveness of adherence counselling in reversing virological failure among patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. HIV Med. 2020;21(1):21–9.

Fox MP, Berhanu R, Steegen K, Firnhaber C, Ive P, Spencer D, Mashamaite S, Sheik S, Jonker I, Howell P, et al. Intensive adherence counselling for HIV-infected individuals failing second-line antiretroviral therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(9):1131–7.

Eholie SP, Moh R, Benalycherif A, Gabillard D, Ello F, Messou E, Zoungrana J, Diallo I, Diallo M, Bado G. Implementation of an intensive adherence intervention in patients with second-line antiretroviral therapy failure in four west African countries with little access to genotypic resistance testing: a prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(11):e750–9.

Jopling R, Nyamayaro P, Andersen LS, Kagee A, Haberer JE, Abas MA. A cascade of interventions to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy in African Countries. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(5):529–46.

Bvochora T, Satyanarayana S, Takarinda KC, Bara H, Chonzi P, Komtenza B, Duri C, Apollo T. Enhanced adherence counselling and viral load suppression in HIV seropositive patients with an initial high viral load in Harare, Zimbabwe: Operational issues. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211326.

Venter WDF, Moorhouse M, Sokhela S, Fairlie L, Mashabane N, Masenya M, Serenata C, Akpomiemie G, Qavi A, Chandiwana N, et al. Dolutegravir plus two different prodrugs of Tenofovir to treat HIV. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):803–15.

Garone D, Conradie K, Patten G, Cornell M, Goemaere E, Kunene J, Kerschberger B, Ford N, Boulle A, Van Cutsem G. High rate of virological re-suppression among patients failing second-line antiretroviral therapy following enhanced adherence support: A model of care in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Southern Afr J HIV Med. 2013;14(4):170–5.

Billioux A, Nakigozi G, Newell K, Chang LW, Quinn TC, Gray RH, Ndyanabo A, Galiwango R, Kiggundu V, Serwadda D: Durable suppression of HIV-1 after virologic monitoring-based antiretroviral adherence counseling in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS One 2015, 10(5).

Cohen J, Pepperrell T, Venter WDF. The same lesson over and over: drugs alone will not get us to 90–90–90. AIDS. 2020;34(6):943–6.

UNAIDS: Understanding Fast-Track: Accelerating Action to End the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. In.: Author Geneva; 2015.

Ford N, Orrell C, Shubber Z, Apollo T, Vojnov L. HIV viral resuppression following an elevated viral load: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(11):e25415.

Ssemwanga D, Asio J, Watera C, Nannyonjo M, Nassolo F, Lunkuse S, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Sanyu G, Lutalo T, et al. Prevalence of viral load suppression, predictors of virological failure and patterns of HIV drug resistance after 12 and 48 months on first-line antiretroviral therapy: a national cross-sectional survey in Uganda. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75(5):1280–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Gomba district personnel whose contributions made this work possible. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Gomba district personnel.

Funding

This study was solely funded by RN. AM was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants K43 TW010695 and R34 MH121084). The content is entirely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Gomba district administration. The authors report no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RN designed the study, performed data collection and statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript along with AM. RMK and RM supported data collection and analysis. GK, NM, CNK, HK, IKK, CN, SK, ZL and JAB participated in study conception and interpretation of results. AM and HD actively supervised all stages of the study including manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Approval to conduct this retrospective chart review was obtained from the University of Liverpool Board of Ethics (H00057734), Mildmay Uganda Research Ethics Committee (0208–2018) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS255ES). Administrative clearance was obtained from the District Health Officer of Gomba district.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakalega, R., Mukiza, N., Debem, H. et al. Linkage to intensive adherence counselling among HIV-positive persons on ART with detectable viral load in Gomba district, rural Uganda. AIDS Res Ther 18, 15 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00349-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00349-9