Abstract

Background

The management of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in HIV-infected patients is often complex with patients experiencing higher mortality rates, more toxic side effects and a higher possibility of treatment failure and relapse than HIV-negative individuals with VL.

Case presentation

We report on successful salvage therapy in two HIV-infected patients suffering with disseminated cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis, recalcitrant to therapy with liposomal amphotericin B. After the employment of combination anti-leishmanial treatment, parasite genomes were not detectable up to the last follow up visit, 57 and 78 weeks after treatment onset, respectively. CD4+ lymphocyte counts fluctuated over time, but were generally higher than counts detected at treatment onset, which likely contributed to protection against VL relapse.

Conclusions

Results achieved with the anti-leishmanial combination treatment were promising, but are based on only two patients. Future investigation is necessary to confirm the efficacy of this salvage therapy in sustaining the immunological response and control of VL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and HIV co-infection is common in tropical areas and can occur in southern European countries [1]. Concerning the WHO European Region, the estimated annual incidence of VL/HIV co-infection is around 1100–1900 cases/year [2]. The Leishmania-HIV interplay at the cellular and molecular level appears to affect the course of infection for both pathogens [3] as VL hampers the immunological competence of HIV-positive patients, while HIV-infected patients with VL exhibit reduced anti-leishmanial drug response, frequent relapses and higher mortality rates than HIV-negative individuals [1, 2]. A combination anti-leishmanial therapy might be considered in HIV/VL co-infection, especially for HIV patients with refractory cases of VL [4, 5]. Nevertheless, a valuable multidrug therapy and optimal treatment duration have yet to be established.

Case description

We report on two patients with Leishmania infantum-induced VL and HIV-1 co-infection who received an extended course of a salvage therapy (anti-leishmanial combination treatment, cAnti-Leish) in addition to antiretroviral therapy (ART). The rationale behind multidrug therapy against Leishmania was to increase drug activity with compounds targeting different pathways of the parasite metabolism, ultimately preventing the emergence of drug resistance. Drugs with distinct activity against Leishmania were used, including those targeting ergosterol biosynthesis (liposomal amphotericin B [L-amB] and fluconazole) and cell membrane integrity (L-amB), modulating surface signaling pathways (miltefosine) interfering with the purine salvage pathway (allopurinol) and hindering DNA synthesis at mitochondrial level (pentamidine) [6, 7]. Furthermore, HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PI) were employed as adjunctive anti-leishmanial therapy for HIV-associated VL [8]. In fact, in vitro [9] and in vivo [10] evidence suggests that high dose PI hamper Leishmania replication and exhibit synergistic effect with L-amB and miltefosine [10].

Our regimen resulted in good control of VL and HIV-1 infection in both patients, whereas previously administered conventional monotherapy with L-amB (dosage regimen of 4 mg/kg on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 31 and 38, for a total dose of 40 mg/kg) followed by secondary prophylaxis (3 mg/kg every 4 weeks) did not prevent multiple VL relapses. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients included in the study.

Case 1 was a 55-year-old man who presented at the Unit of Infectious Diseases, Forlì Hospital (northeastern Italy) with a 4-year history of HIV infection and a 2-year history of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis. Despite being under secondary prophylaxis with L-amB, severe gastroenterological disease caused by Leishmania was discovered. Case 2 was a 50-year old HIV-positive man who presented with a 6-year history of HIV infection and a 3-year history of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis and VL, recalcitrant to therapy with L-amB.

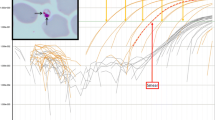

Leishmanial DNA was detected by real-time PCR in the peripheral blood, bone marrow aspirates and skin biopsies of both patients (Fig. 1 and not shown). Additionally, stomach and colon biopsies from Case 1 tested positive for leishmanial DNA. In both cases, bone marrow showed high levels of parasitemia (around 10E6 parasite genomes/mL), while lower levels (around 10E2–10E3 parasite genomes/mL) were detected in peripheral blood (Fig. 1). Patients exhibited a CD4+ count of 225 cells/μL and 170 cells/μL before cAnti-Leish, Case 1 and Case 2, respectively. The nadir CD4 cell count was 120 cells/μL and 143 cells/μL, Case 1 and Case 2, respectively.

Time course of parasitological and immunological parameters upon combined anti-leishmanial treatment in Case 1 (a) and Case 2 (b). Parasitemia (red circles) was measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) before and after anti-leishmanial combination (cAnti-Leish) treatment. Also shown is the CD4+ cell count in peripheral blood (empty squares; normal range: 500–1500 cells/μL). HIV RNA was < 40 copies/mL in Case 1 and Case 2 throughout the study as tested by the Veris DxN HIV-1 assay (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA USA). Leishmanial DNA was detected in peripheral blood by two distinct real-time (RT) PCR assays, amplifying segments of the small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene and the kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) [15]. Samples testing positive for parasitic DNA were then quantified by RT-PCR for the single copy polymerase gene (pol) of Leishmania [16]. The detection limit was 0.00005 parasite/reaction for kDNA RT-PCR and 1 parasite/reaction for pol RT-PCR. Leishmania typing was performed by hsp70 PCR [17] and L. infantum was identified in both patients. ▲: Parasitemia was quantified in bone marrow aspirates within one week before cAnti-Leish onset

High and intermittent doses of L-amB in 5% dextrose i.v. infusion over 4 h (4 mg/kg/day on days 1–5, 10, 17, 24, 32 and 38) were administered for VL treatment [1, 4]. The patients also received concomitant miltefosine (50 mg three times/day for 28 days), allopurinol (300 mg four times daily for 15 days) and de-escalating doses of fluconazole (from 600 to 400 mg/day for 28 days). Since PI can also be considered an adjunctive anti-leishmanial therapy, ART was modified by adding a boosted PI treatment, including darunavir (800 mg/day) and ritonavir (100 mg/day) in Case 1 and atazanavir (300 mg/day) and ritonavir (100 mg/day) in Case 2, respectively, while the backbone therapy included lamivudine 300 mg/day and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (245 mg/day) in both patients. Once remission was achieved, including resolution of fever, remarkable improvement of the patient’s general condition, regression of splenomegaly and amelioration of laboratory parameters, a maintenance treatment was instituted for 12 weeks with L-AmB (2–3 mg/kg every 3 weeks), miltefosine (50 mg three times weekly), allopurinol (300 mg twice daily), fluconazole (400 mg/day) and pentamidine aerosol (300 mg twice a month for the first 2 months, then once a month for 6 months). One week after cAnti-Leish onset, there was a significant decline in peripheral blood parasitemia (Fig. 1); we observed a good correlation between clinical outcome and blood parasite burden. To consolidate activity against potentially residual parasites, a second cycle of the initial and maintenance therapy was given to both patients (Case 1 only received 2 mg/kg L-Amb in the second cycle). Secondary prophylaxis with L-Amb (2–3 mg/kg every 3–4 weeks) was subsequently administered. Parasite genomes were not detectable over time up to the last follow-up visit (Week 57 and Week 78 for Case 1 and Case 2, respectively). CD4+ lymphocyte counts fluctuated over time, but were generally higher than counts detected at treatment onset, which likely contributed to protection against VL relapse.

Discussion and conclusions

It has been suggested that combined drug regimens are the best option for VL/HIV co-infected patients by increasing drug efficacy, reducing toxicity and hampering the emergence of resistance [4, 5]. So far, the best combination therapy appears to be L-amB plus miltefosine due to the observed synergism between the two compounds in vitro and in animal models [11]. Furthermore, a combination regimen consisting of L-amB and miltefosine was employed in VL/HIV co-infected patients in a pilot study performed by Médecin Sans Frontières in Ethiopia [12] as well as in 120 VL/HIV co-infected patients in India [13], showing encouraging results.

Here, the employment of L-amB and miltefosine was associated to other drugs with anti-leishmanial effects, including fluconazole, allopurinol and pentamidine. Results achieved with cAnti-Leish were promising, but are based on only two patients. Thus, future investigation is necessary to confirm the efficacy of this salvage therapy. Furthermore, the potentially synergistic role of cAnti-Leish and a PI-based ART regimen in sustaining the immunological response and control of VL should be further explored as recent evidence suggests that both CD4+ count and circulating Leishmania DNA contribute to prognosis in HIV/VL co-infection [14].

References

Monge-Maillo B, Norman FF, Cruz I, Alvar J, Lopez-Velez R. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV coinfection in the Mediterranean region. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3021.

Gradoni L, Rogelio LV, Mourad M. Regional Office for Europe. Manual on case management and surveillance of the leishmaniases in the WHO European Region. WHO 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/manual-on-case-management-and-surveillance-of-the-leishmaniases-in-the-who-european-region-2017.

Okwor I, Uzonna JE. The immunology of Leishmania/HIV co-infection. Immunol Res. 2013;56:163–71.

Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R. Treatment options for Visceral Leishmaniasis and HIV coinfection. AIDS Rev. 2016;18:32–43.

Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, Pearson R, Lopez-Velez R, Weina P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202–64.

Maes L, da Luz RAI, Cos P, Yardley V. Classical versus novel treatment regimens. In: Ponte-Sucre A, Diaz E, Padrón-Nieves M, editors. Drug resistance in Leishmania parasites. Vienna: Springer; 2013. p. 301–20.

Singh OP, Sundar S. Immunotherapy and targeted therapies in treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: current status and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2014;5:296.

van Griensven J, Diro E, Lopez-Velez R, Boelaert M, Lynen L, Zijlstra E, et al. HIV-1 protease inhibitors for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-co-infected individuals. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:251–9.

Trudel N, Garg R, Messier N, Sundar S, Ouellette M, Tremblay MJ. Intracellular survival of Leishmania species that cause visceral leishmaniasis is significantly reduced by HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1292–9.

Valdivieso E, Mejías F, Carrillo E, Sánchez C, Moreno J. Potentiation of the leishmanicidal activity of nelfinavir in combination with miltefosine or amphotericin B. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:682–7.

Seifert K, Croft SL. In vitro and in vivo interactions between miltefosine and other antileishmanial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:73–9.

Akuffo H, Costa C, van Griensven J, Burza S, Moreno J, Herrero M. New insights into leishmaniasis in the immunosuppressed. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006375.

Mahajan R, Das P, Isaakidis P, Sunyoto T, Sagili KD, Lima MA, Mitra G, Kumar D, Pandey K, Van Geertruyden JP, Boelaert M, Burza S. Combination treatment for visceral leishmaniasis patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus in India. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1255–62.

Cota GF, de Sousa MR, de Assis TSM, Pinto BF, Rabello A. Exploring prognosis in chronic relapsing visceral leishmaniasis among HIV-infected patients: circulating Leishmania DNA. Acta Trop. 2017;172:186–91.

Varani S, Ortalli M, Attard L, Vanino E, Gaibani P, Vocale C, et al. Serological and molecular tools to diagnose visceral leishmaniasis: 2-years’ experience of a single center in Northern Italy. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183699.

Mary C, Faraut F, Lascombe L, Dumon H. Quantification of Leishmania infantum DNA by a real-time PCR assay with high sensitivity. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5249–55.

Van der Auwera G, Maes I, De Doncker S, Ravel C, Cnops L, Van Esbroeck M, et al. Heat-shock protein 70 gene sequencing for Leishmania species typing in European tropical infectious disease clinics. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20543.

Authors’ contributions

AM conceptualization, SV, PG, GRo, CV, GRa, VS, MCR methodology and data curation, AM and SV writing—original draft preparation; VS, MCR, PG, GRo, CV, GRa writing—review and editing; VS, MCR resources. AM was Head of the Unit of Infectious Diseases, “G.B. Morgagni-L. Pierantoni” Hospital, Forlì (Italy) at the time of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Martina Moriconi, Elena Carra and Gianluca Rugna for identification of Leishmania species. Anne Collins edited the English text.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed signed consent was obtained from the two patients included in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by Lab P3 funds from the Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy) and by RFO 2010–2015 funds from the University of Bologna.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mastroianni, A., Gaibani, P., Rossini, G. et al. Two cases of relapsed HIV-associated visceral leishmaniasis successfully treated with combination therapy. AIDS Res Ther 15, 27 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-018-0215-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-018-0215-x