Abstract

Background

Previous studies have not synthesized existing literature on the lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents (aged 10–19) in Africa. Such evidence synthesis is needed to inform policies, programs, and future research to improve the well-being of the millions of pregnant or parenting adolescents in the region. Our study fills this gap by reviewing the literature on pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa. We mapped existing research in terms of their substantive focus, and geographical distribution. We synthesized these studies based on thematic focus and identified gaps for future research.

Methods

We used a three-step search strategy to find articles, theses, and technical reports reporting primary research published in English between January 2000 and June 2021 in PubMed, Jstor, AJOL, EBSCO Host, and Google Scholar. Three researchers screened all articles, including titles, abstracts, and full text, for eligibility. Relevant data were extracted using a template designed for the study. Overall, 116 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Data were analyzed using descriptive and thematic analyses.

Results

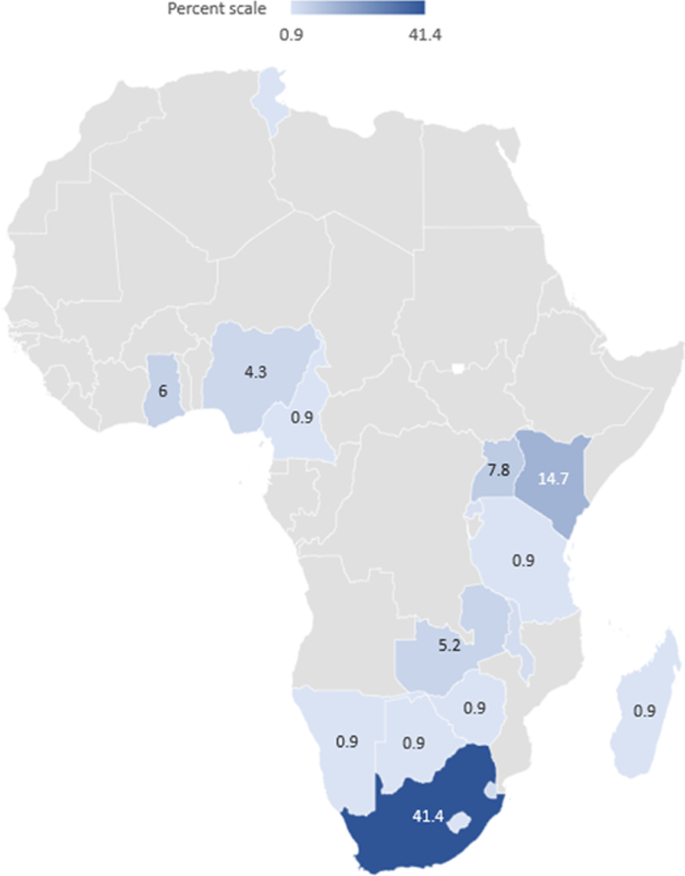

Research on pregnant and parenting adolescents is limited in volume and skewed to a few countries, with two-fifths of papers focusing on South Africa (41.4%). Most of the studies were African-led (81.9%), received no funding (60.3%), adopted qualitative designs (58.6%), and were published between 2016 and 2021 (48.3%). The studies highlighted how pregnancy initiates a cycle of social exclusion of girls with grave implications for their physical and mental health and social and economic well-being. Only 4.3% of the studies described an intervention. None of these studies employed a robust research design (e.g., randomized controlled trial) to assess the intervention’s effectiveness. Adolescent mothers' experiences (26.7%) and their education (36.2%) were the most studied topics, while repeat pregnancy received the least research attention.

Conclusion

Research on issues affecting pregnant and parenting adolescents is still limited in scope and skewed geographically despite the large burden of adolescent childbearing in many African countries. While studies have documented how early pregnancy could result in girls' social and educational exclusion, few interventions to support pregnant and parenting adolescents exist. Further research to address these gaps is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One group of young people that has received limited attention in sexual and reproductive health and rights research is pregnant and parenting adolescents (aged 10–19). This group of adolescents faces daunting challenges as they navigate parenthood, care for their babies, and improve their lives [1,2,3]. Many forfeit their future aspirations, including their educational goals and skills acquisition, with significant implications for their health and well-being, as well as that of their offspring [4,5,6].

Girls who become pregnant outside marriage often face stigma because of widespread socio-cultural and religious beliefs that sex should only occur in marriage [7]. As a result, some face an an hostile home environment or move away from home to reside with their partners [8]. Further, girls who become pregnant while in school are often forced to drop out of school [9]. This situation initiates a cycle of events culminating in their social exclusion. Social exclusion of pregnant and parenting adolescents can jeopardize the immediate and future health and well-being of young mothers. Patton et.al. argues that adolescence offers huge opportunities to alter negative and harmful trajectories that can jeopardize their future health. In their Lancet Commission, they demonstrate that investing in adolescent health, education and family would yield a triple dividend of benefits in the development of capabilities during adolescence, future adult-health trajectories, and secure welfare of the next generation [10].

Despite the existence of school reentry policies in most African countries that should facilitate reentry, available estimates show that a vast majority of pregnant and parenting adolescents are out of school even though they would like to return to school [11]. The few that manage to return to school describe the school environment as hostile, discriminatory, and inflexible [12]. Teachers unfairly target them, resulting in them dropping out or infrequently attending school [13].

Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood are also associated with child marriage, as these adolescents may be forced to move in with or get married to their partners [14, 15]. For some adolescent girls who become pregnant outside of wedlock, marriage serves as the only option to escape the associated stigma and social exclusion, enhance their status in the community or get financial support to care for their children [16]. However, child marriage can expose adolescent mothers to mental problems [17], school dropout [18], and intimate partner violence [19].

The social exclusion of pregnant and parenting adolescents has grave implications for gender equality. Because they rarely return to school [11], pregnant and parenting adolescents are unable to achieve their educational goals, which has consequences for their participation in the labor force [4]. Ultimately, this disenfranchises them and their children. Even though there are review studies on adolescent sexual and reproductive health, experience of adolescent mothers affected by HIV, and adolescent mental health in Africa [20, 21], there is limited attention to the lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Given the unique challenges facing this cohort of adolescents, it is pertinent to review the literature to identify gaps in research on this population. Also, noting that a quarter of adolescent girls are either pregnant or parenting in the region, there is a need to target this population for interventions [22].

A review of existing studies will inform our knowledge of what interventions exist to improve their health and well-being as well as their socioeconomic and education empowerment and identify areas to prioritize for interventions. Our scoping review addresses this gap, drawing on the social exclusion framework [23], and aims to answer three questions: (1) What is the profile of research on the lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in terms of research designs, geographical distribution and substantive focus, including motherhood, and experiences in the community and schools? (2) How does early childbearing impact pregnant and parenting adolescents’ mental health? (3) What interventions are reaching adolescent mothers to improve their health and socioeconomic wellbeing?

Methods

A scoping review is the appropriate design for the study given we aim to explore the breadth and extent of the literature, map and summarize the evidence, and inform future research, of the broader objective of this review.

Search strategy

Guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological approach, we searched for peer-reviewed papers and grey literature published between January 2000 and June 2021 on pregnant and parenting adolescents. Grey literature was limited to theses. The search was limited to documents published in the English language and focusing on African countries. A three-step search strategy was used to ensure our search was comprehensive. First, we conducted a limited PubMed search to identify medical subject heading (MesH) terms for pregnant adolescents, adolescent mothers, and adolescent fathers. We analyzed the text words in the title, abstracts, and index terms in the articles from the initial search. We then created search terms for the study using the results of our analysis. In the second step, we searched PubMed, Jstor, AJOL, EBSCO Host, and Google scholar. After removing duplicates from the initial articles, we identified review studies found during our search. We reviewed the reference lists of these review articles and identified articles from the list that met our inclusion criteria. A detailed sample of PubMed search is provided in Additional file 1.

Eligibility criteria

We included articles focusing on pregnant and parenting adolescents (married and unmarried) published in English between January 2000 and June 2021. As we aimed to identify gaps in research on pregnant and parenting adolescents with a specific focus on the challenges they face and interventions to address them, we only included articles that focused on parenting adolescents' well-being, including school reentry, livelihood, and repeat pregnancy, contraceptive use, mental health, motherhood challenges and care-seeking practices, and programs reaching pregnant and parenting adolescents. We excluded studies focusing on maternal health care services utilization, obstetric outcomes and adolescent pregnancy rate and risk factors to have a manageable number of articles and because previous systematic review studies have explored these topics [24,25,26] (Table 1).

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened the articles' titles and abstracts to assess their eligibility. Articles were included if they met the pre-specified inclusion criteria and if both reviewers agreed. When there was disagreement, a discussion was held with a third reviewer to resolve it. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating the process of article screening, inclusion, and exclusion. The initial search yielded a total of 427 articles, from which we removed 188 duplicates. After screening abstracts and titles, we excluded 112 articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria. We assessed the full text of a total of 127 articles and further removed 11 articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria, leaving 116 articles in our analysis.

Data extraction and charting

We developed a data extraction template using Microsoft Excel. Three members of the research team completed the data extraction. Specifically, we extracted the country of affiliation of the first and last authors, country of study and sub-region, year of publication, journal of publication, study design, study objectives, key findings, and funder. We also classified the articles into common themes, including contraceptive use, mental health, lived experiences, education, social support, motherhood, care-seeking practices, and repeat pregnancy and HIV. One member of the research team reviewed samples of the extracted data for quality assurance.

Evidence synthesis

We synthesized the data using descriptive statistics and content analysis. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the studies in terms of geographic distribution, year of publication, thematic focus, and research design. We summarized the key findings under the themes generated.

Results

Overall, 116 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. About half of the studies were published between 2016 and 2021 (48.3%). The studies were conducted in 17 African countries, and two-fifth of them focused on South Africa (41.4%) (Fig. 2). As shown in Table 2, most of the studies were African-led (81.9%). Only a few of the studies (4.3%) described an intervention, and none of these intervention studies employed a robust research design (e.g., randomized controlled trial design) to assess its effectiveness and impact. Qualitative methodology was the most commonly used study design (58.6%), enabling a deeper understanding of adolescent mothers' challenges. Adolescent mothers' experiences (26.7%) and their education (36.2%) were the most studied topics, while repeat pregnancy received the least research attention. Close to two in three studies did not receive any funding; 30.2% received external funding, while 9.5% had local funding. Organizations and agencies in the United States funded 37.1% of studies (n = 35) that received external funding. The United Kingdom (14.3%), Netherlands (14.3), Sweden (11.4%), and Canada (8.6%) governments were also prominent funders of research on pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa.

Partners, parents and community reactions to and support for pregnant and parenting adolescents

Partners, parents and community reactions to and support for pregnant and parenting adolescents were the areas that have received the most research attention [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. However, eighteen of the 30 studies were conducted in South Africa. Most adolescent girls described their pregnancy as unintended [28, 29] and owing to transactional sex to meet their basic needs, sexual violence and exploitation, and lack of accurate information on methods of preventing pregnancy. A few adolescents wanted to become pregnant to command respect from people. Most were still in school when they became pregnant—many experienced denials of paternity [30, 31]. Boys were reported to deny paternity because they thought admitting it would jeopardize their educational and employment opportunities. As a result, adolescent mothers had limited support from the boys or their parents. Adolescent girls’ reactions to their pregnancy ranged from disappointment, anger, regret, and anxiety, for many, to a personal sense of satisfaction, happiness, and accomplishment, for a few [32].

Family reactions to adolescent pregnancy and motherhood were largely negative [30, 31, 33] and ranged from anger, disappointment, abandonment, rejection, and physical and emotional violence. In studies in Ghana and South Africa, parents and guardians of adolescent mothers were upset in the initial stages when they heard the news of the pregnancy, but they subsequently turned the initial emotion into forgiveness and acceptance. Lack of support from families, friends, and society was reported in Nigeria [33]. In Swaziland [32] and South Africa [34], adolescent pregnancy strained relationships with fathers, but mothers provided emotional and material support [32].

Adolescent mothers were noted to experience extreme hardship, educational disruption, stigma, stress, loneliness, guilt, and harsh treatment from family, schools, hospitals, and community members [35, 36]. They also faced financial constraints and food insecurity, prompting some to take up menial jobs. They faced unfavorable health [37] and school systems [38] emanating from discrimination by health workers, abuse and mockery from teachers, and stigma from peers [35]. This, in return, restricted them from effectively managing their schoolwork and parenting roles and resulted in delays in healthcare seeking and poor performance in school. Their pregnancy was seen as a major impediment to their education and career aspirations. Others were forced into early marriages and left feeling rejected. The negative treatment of pregnant and parenting adolescents was associated with skill gaps in handling parenting adolescent needs among key stakeholders, including parents, teachers, and service providers. Positive experiences included parenting adolescents’ views of their children as a source of meaning and the aspirations they had for their children [39]. Also, despite these challenges, adolescent mothers in South Africa were more likely to report parental support [28].

Only four studies focused on the experiences of adolescent fathers [40,41,42,43] and were conducted in South Africa. Peer influence, misconceptions about contraceptives, multiple partners, and low education attainment were associated with adolescent fatherhood. The studies found that adolescent fathers' own experience of absent fathers gave them a strong sense of responsibility towards their children and partners, but they faced financial constraints and were emotionally, psychologically, and socioeconomically overwhelmed by parental responsibilities. Adolescent fatherhood was related to stress and feelings of low confidence due to stigma related to becoming a father too early. Some had to work to support their children.

School reentry policies and experiences of adolescent mothers in school

Forty-two studies focused on school reentry policies and adolescent mothers' experiences in school [5, 7, 11, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. These studies are mainly from South Africa (19 publications), Kenya (11 publications), Zambia (six publications), Ghana (two publications), Eswatini (one publication), Tanzania (one publication), Namibia (one publication), and Ghana (one publication). The review shows that most countries studied have school reentry policies in place while others are in the process of drafting or finalizing a policy [60]. In Kenya, there is a school reentry policy, but key stakeholders are unfamiliar with the provisions within the policy and are unable to fully implement policy [49]. Thus, 98% of adolescent mothers were reported to be out of school [56]. A lack of proper monitoring systems to ascertain conformity with the guidelines and limited circulation to headteachers and principals were noted [60]. In Zambia, pregnant girls were reported to drop out of school voluntarily or involuntarily as soon as the pregnancy is visible. On return to school, they experienced discrimination, mockery, abuse, humiliation, labeling, and isolation from teachers, peers, friends, classmates, and community members [7]. Their social exclusion resulted in low self-esteem, identity crises, poor academic performance, alcohol use, truancy, and running away from home [7]. Parents and adolescent mothers lacked information about the school reentry policy and guidelines resulting in the limited implementation of the policy [80]. Also, preference for boys’ education and poverty affected adolescent mothers' education with parents not willing or lacking resources to fund their education [57, 80].

While most adolescent mothers wanted to reenter school, they were constrained with child care responsibilities coupled with various contextual barriers, including financial burden, lack of emotional and social support, culture, lack of policy guidelines, fear of the school being ostracized by the community, fear of having mothers at school, and political factors, which impeded their full reintegration in school and impacted negatively on their school performance [11, 56, 60]. These contextual barriers suppressed the implementation of school reentry policies, especially in very conservative communities. Prevailing negative factors such as childcare responsibilities, poor economic background, and unsympathetic teachers and schoolmates made it difficult for adolescent mothers to reintegrate back into school [60]. Almost all adolescent mothers indicated that financial support for school fees and other expenses is critical for their reentry back to school. Only a few mentioned the need for childcare support. A study in Kenya found that school environment, teacher encouragement, school clubs, school sponsors, attitudes of other learners, the attitude of the school principal, teacher parenting program, curriculum, guidance and counseling services, opportunities to take part in activities and perform duties, motivational talks by resource persons, time for arrival and departure from school are factors facilitating the education of adolescent mothers [79].

In South Africa, however, many adolescent mothers returned to school. But, there were concerns that they return too early, as early as the first two months of postpartum [63]. Their return to school was fraught with challenges like limited support, social stigma, verbal abuse, and discrimination, resulting in many quitting schools or not succeeding with schooling [46, 48]. Adolescent mothers also struggled with balancing childcare with school demands [45]. But teachers were aware of their constitutional right to education and painstakingly protected this right [47].

Mental health

Few studies have focused on the mental health of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Except for two studies, the rest were published between 2015 and 2021 [20, 81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96]. They concentrated on Zimbabwe [87], Nigeria [81, 85], South Africa [86, 92, 95], Kenya [83, 91, 93], Uganda [82, 88], Rwanda [94], and Lesotho [90]. One study looked at data from across sub-Saharan Africa [16], while one focused on global data[84]. Except for one intervention study, all these studies described the mental health challenges faced by pregnant, and parenting adolescents (including suicidal ideation, stress, anxiety, hearing voices, depression), the key stressors increasing their risk to mental distress, and challenges they experienced in accessing care.

These studies demonstrate that pregnant and parenting adolescents face high levels of depression, stress, and anxiety, heightened by their social exclusion, poverty, intimate partner violence, rejection by partners and parents after becoming pregnant, stigma from the community, chronic illnesses like HIV, and childhood vulnerabilities. The prevalence of depression ranged from 13% in Zimbabwe [87], 16% in South Africa [92], 48% in Rwanda [94], and 33% [93], and 53% [91] in Kenya. Common risk factors for depression included physical violence, verbal abuse, intimate partner violence [92], low family income, psychoactive substances [91], having experienced stressful life events, being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, absence of social support, abandonment by a partner, absence of both parents during childhood [93], social insecurity, negative perception of teenage pregnancy, and bad relationships within families [87]. Protective factors included partner support [92]. Postpartum depression among adolescent mothers was associated with parental distress, weight/body shape disturbances, economic income, and parental-child dysfunctional interaction [94].

Negative service providers’ attitudes and stigma towards mental illness [85] and adolescent pregnancy, lack of confidentiality, and logistic and environmental challenges prevented the use of mental health services [86]. The lack of an all-inclusive approach to address adolescent parents’ multiple needs, including inadequate capacity and training for healthcare providers on handling their needs, was another challenge. Limited evidence exists on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on mental health disorders, prevention or treatment of common mental illnesses for adolescent mothers, particularly from low- or middle-income countries to inform effective intervention strategies for mental health illnesses.

Motherhood challenges and care-seeking practices

A few studies focused on the challenges faced by adolescent mothers and care-seeking behaviors [97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107]. These studies were conducted in Uganda, South Africa, Swaziland, and Ghana with one study focusing on sub-Saharan Africa. The findings highlighted adolescent mothers' limited knowledge and skills about newborn/childcare practices. They often resorted to practices deemed harmful to their children [102], such as applying hot towels heated with hot stones to children's umbilical stump [102, 104]. Further, early motherhood was noted to strip adolescent girls of their agency and expose them to the stigma that compounds their barriers to accessing care during and after pregnancy. As a result, adolescent mothers may face more challenges during pregnancy and early motherhood than adult mothers.

Contraception

Only seven studies focused on contraception among parenting adolescents [82, 108,109,110,111,112,113], four were published between 2001 and 2004, and two were published in 2020. These studies focused on contraceptive knowledge, attitude, perceptions, and use and were conducted in Cameroon, Nigeria, South Africa, Malawi, and Uganda. The studies highlighted low contraceptive uptake or the use of less effective methods like periodic abstinence, herbal concoctions, and vaginal douching [108]. However, in Uganda, Muyama et al. [82] reported a relatively high uptake of contraceptives among adolescent mothers, influenced by the desire to return to school [82]. The findings in terms of contraceptive knowledge were mixed with the study conducted in Nigeria, showing that contraceptive knowledge is poor. In contrast, the study in Cameroon found that most adolescent mothers had heard about contraceptives [111]. A study in South Africa reported several barriers to contraceptive use among parenting adolescents, including fear of side effects, partner rejection, providers' attitudes, and shortage of contraceptive supplies [112].

Repeat pregnancy

Just three studies focused on repeat pregnancy among adolescent mothers, and all were conducted in South Africa [114,115,116]. The prevalence of repeat pregnancy in South Africa ranged from 17.6% to 19.9%. A history of spontaneous abortion, contraceptive use, a higher level of education, and emotional support were protective against repeat pregnancy. However, HIV-positive status, having more than one sexual partner and having a partner that is at least five years older were risk factors for repeat pregnancy. Adolescent mothers who received medical, psychosocial, educational, and family planning support experienced lower repeat pregnancy rates.

Programs reaching pregnant and parenting adolescents

Five studies described programs targeting adolescent mothers [117,118,119,120,121]. Two of these five papers reported on one program—the Teenage Mothers project—implemented in Uganda [120, 121]. The program used an iterative, bottom-up, participatory approach to co-design an intervention to improve the psychological and social well-being of unmarried adolescent mothers. The program encompassed five intervention components: community awareness-raising, teenage mother support groups, formal education and income generation, counseling, and advocacy. The program was evaluated using qualitative research, and the findings suggest that it contributed to the teenage mothers' well-being and supportive social environment and community norms towards their future opportunities. Results also suggested that the program increased agency, improved coping with early motherhood and related stigma, continued education, and increased income generation. However, the program was not effective in changing community norms regarding out-of-wedlock sex and pregnancy [120].

Another study in Kenya used young mothers' clubs to increase adolescent mothers' knowledge of family planning and postpartum hemorrhage [118]. Young mothers participating in the program met weekly to share experiences and solutions to their challenges while receiving health education from health facility staff and community health workers.

Another intervention was implemented in Malawi to improve adolescent mothers' well-being and promote the healthy upbringing of their children. The program was informed by a literature review and consultation with key stakeholders. A safe space was created to share the daily challenges faced by adolescent mothers. Key stakeholders were brought to teach mothers about various topics like brain development, hygiene, and nutrition. Their children were provided with early childhood education and stimulation activities for up to two and a half years. Lastly, there was a community advocacy component to ensure the continued support of adolescent mothers.

As part of the fourth intervention, adolescent mothers in South Africa were introduced to kangaroo mother care to improve their childcare practices [119]. Kangaroo mother care is the practice of skin-to-skin contact between an infant and parent and has been found to improve growth and decrease the morbidity and mortality of low-birth-weight and premature infants [119]. Adolescent mothers in this intervention reported positive feelings about the kangaroo mother care. They also reported positive interactions with nurses, doctors, and other mothers and were pleased with the physical, emotional, social, and discharge support they received. However, they considered kangaroo mother care boring because they would just sit with their babies and do nothing.

Discussion

Ours is the first study to our knowledge to synthesize existing literature on the experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa. Research on pregnant and parenting adolescents is generally limited in volume and skewed to a few countries despite most countries recording a high prevalence of adolescent childbearing. The bulk of research on these adolescents is from two countries (South Africa and Kenya), underscoring the gaps in the geographical distribution of research on the issue in the region. These two countries are by far not the ones with the highest prevalence of adolescent childbearing in Africa. The significant research attention on the issues in these countries could make the issues facing pregnant and parenting adolescents more prominent to policymakers. Kenya, for example, formulated and released National Guidelines for School Reentry in Early Learning and Basic Education in 2020 [122]. Without the significant research attention on the issue in Kenya, this may have been impossible.

Despite the limited research attention on the experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents, more recently, there appears to be increasing research attention given that about half of the studies were conducted between 2016 and 2021. Researchers' apparent growing interest in this population of adolescents bodes well for future research and investments in programs to improve their well-being. If the current interest in pregnant and parenting adolescents continues, there is a possibility for filling research gaps and addressing the wide geographical gaps in its distribution.

Unlike research on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in general [123], affiliated African authors led a vast majority of research on pregnant and parenting adolescents’ experiences and challenges. Adolescent sexual and reproductive has received significant research attention given it is one of the global development priority topics. Ending HIV, child marriage, female genital mutilation, early and unintended pregnancy, and increasing contraceptive uptake among adolescents are important global health priorities that have received significant research and program investments. However, issues affecting adolescent mothers have received limited focus, including funding and program investments. It is not surprising that most studies on pregnant and parenting adolescents did not receive any funding. The low representation of global north researchers in publications on these adolescents’ experiences and challenges may reflect the limited research funds available on these issues. Given that millions of girls in the region become pregnant every year, it is important that issues affecting them, particularly their education and skill empowerment, prevention of repeat pregnancy, mental health, and prevention of partner and non-partner violence, gain global attention. Empowering pregnant and parenting adolescents is key to realizing Sustainable Development Goal 5—Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. It is, therefore, imperative that global development partners and governments invest in research and programs to improve their health and well-being.

Our review demonstrates that pregnant and parenting adolescents, particularly girls, face several social, education, health, and motherhood challenges, including stigma, poor mental health, low contraceptive uptake, repeat pregnancy, lack of support, hostile school environment. Yet limited studies report on interventions to address these challenges. Such overwhelming neglect suggests that the suffering and social exclusion of this population of adolescents will continue, resulting in their disempowerment, poverty, and exacerbation of gender inequality. However, it is important to note that there is a range of experiences across the continent and challenges faced by adolescent parents varies hugely depending on the context [63]. For example, adolescent mothers are more likely to return to school in South Africa compared to Kenya, suggesting differential experiences of adolescent mothers in both settings [11, 63]. Also, some countries have formulated school reentry policies to address hostile school environments and facilitate adolescent mothers’ return to school.

While most studies focus on pregnant and parenting adolescents’ lived experiences and education, topics like contraceptive uptake, repeat pregnancy, intimate partner violence, mental health, and interventions to demonstrate what works in improving overall well-being and empowerment have received limited attention. Even though a few studies described an intervention, none used robust research designs to assess their effectiveness. Gaps exist in terms of understanding what works to empower adolescent mothers educationally and economically. Overall, evidence on scalable and cost-effective programmatic responses for adolescent mothers' education and economic empowerment is lacking in sub-Saharan Africa. Also lacking are studies documenting the complex nature of adolescent fatherhood and its impacts on their health and socioeconomic well-being. Overall, the studies were limited in scope and geographical distribution. There is a need for studies on lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in many African countries where no such studies exist. Future studies should document the positive experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents and especially young fathers.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. The articles reviewed are limited to those published in English. Excluding publications written in other languages may have potentially limited the number of studies reviewed. Our search was also limited to online sources and might have missed out on manuscripts not published online. We also did not assess the quality of the studies included. Lastly, since our search was completed in 2021, there is a need for future studies to update this review to keep pace with the evolving research on the topic.

Conclusion

Our review shows that research on lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents is limited in scope and geographical coverage. While studies have documented how early pregnancy could result in girls' social and educational exclusion, few interventions to support and empower pregnant and parentings adolescents exist. Further research is warranted on repeat pregnancy, contraceptive uptake, and exposure to violence among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Further, research on what works to empower these adolescents is needed.

Data availability

All data analysed are in the article.

References

The United Nations Population Fund. Motherhood in childhood: facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy. New York: UNFPA; 2014.

Gomez AM, Arteaga S, Ingraham N, Arcara J, Villaseñor E. It’s not planned, but is it okay? The acceptability of unplanned pregnancy among young people. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):408–14.

Hanna B. Negotiating motherhood: the struggles of teenage mothers. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34(4):456–64.

Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F. Unintended pregnancy and its adverse social and economic consequences on health system: a narrative review article. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(1):12.

Gyan C. The effects of teenage pregnancy on the educational attainment of girls at Chorkor, a suburb of Accra. J Educ Soc Res. 2013;3(3):53.

Rosenberg M, Pettifor A, Miller WC, Thirumurthy H, Emch M, Afolabi SA, et al. Relationship between school dropout and teen pregnancy among rural South African young women. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):928–36.

Nkwemu S, Jacobs CN, Mweemba O, Sharma A, Zulu JM. “They say that I have lost my integrity by breaking my virginity”: experiences of teen school going mothers in two schools in Lusaka Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):62.

Ajayi AI, Akpan W, Goon DT, Nwokocha EE, Adeniyi OV. Tough love: socio-cultural explanations for deadly abortion choices among Nigerian undergraduate students: health. Afr J Phys Activity Health Sci. 2016;22(31):711–24.

Human Rights Watch. Leave No Girl Behind in Africa: Discrimination in Education against Pregnant Girls and Adolescent Mothers. 2018. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/06/14/leave-no-girl-behind-africa/discrimination-education-against-pregnant-girls-and. Accessed 17 July 2021.

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423–78.

Undie C-C, Birungi H, Odwe G, Obare F. Expanding access to secondary school education for teenage mothers in Kenya: A baseline study report. 2015.

Karimi E. Challenges experienced by young mother learners upon reentry to formal primary school. Oslo: Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Oslo; 2015.

Undie C, Birungi H. Are School Principals ‘the Bad Guys’? Nuancing the narrative of school re‐entry policy implementation in Kenya. In: Okwany A, Wazir R, editors. Changing Social Norms to Universalize Girls' Education in East Africa: Lessons from a Pilot Project. 2016. p. 166.

Menon J, Kusanthan T, Mwaba S, Juanola L, Kok M. ‘Ring’your future, without changing diaper–Can preventing teenage pregnancy address child marriage in Zambia? PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10): e0205523.

Steinhaus M, Hinson L, Rizzo AT, Gregowski A. Measuring social norms related to child marriage among adult decision-makers of young girls in Phalombe and Thyolo, Malawi. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(4):S37–44.

Schaffnit SB, Wamoyi J, Urassa M, Dardoumpa M, Lawson DW. When marriage is the best available option: perceptions of opportunity and risk in female adolescence in Tanzania. Glob Public Health. 2020;16:1–14.

Gage AJ. Association of child marriage with suicidal thoughts and attempts among adolescent girls in Ethiopia. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):654–6.

Sekine K, Hodgkin ME. Effect of child marriage on girls’ school dropout in Nepal: Analysis of data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0180176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180176.

Ahinkorah BO, Onayemi OM, Seidu A-A, Awopegba OE, Ajayi AI. Association between girl-child marriage and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. J Interpers Violence. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211005139.

Roberts KJ, Smith C, Cluver L, Toska E, Sherr L. Understanding mental health in the context of adolescent pregnancy and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review identifying a critical evidence gap. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:2094–107.

Toska E, Laurenzi CA, Roberts KJ, Cluver L, Sherr L. Adolescent mothers affected by HIV and their children: a scoping review of evidence and experiences from sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Public Health. 2020;15(11):1655–73.

UNICEF. Early childbearing and teenage pregnancy rates by country New York, United States: UNICEF; 2021. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/adolescent-health/. Accessed 16 July 2021.

Sen A. Social exclusion: concept, application, and scrutiny. Manila: Asian Development Bank; 2000.

Fasula AM, Chia V, Murray CC, Brittain A, Tevendale H, Koumans EH. Socioecological risk factors associated with teen pregnancy or birth for young men: a scoping review. J Adolesc. 2019;74:130–45.

Yakubu I, Salisu WJ. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4.

Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T, Osornio-Vargas A, Chandra S, Voaklander D, et al. Social determinants of health and adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):88–99.

Mngadi PT, Zwane IT, Ahlberg BM, Ransjö-Arvidson AB. Family and community support to adolescent mothers in Swaziland. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(2):137–44.

Mjwara N, Maharaj P. Becoming a mother: perspectives and experiences of young women in a South African Township. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(2):129–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1334963.

Gyesaw NYK, Ankomah A. Experiences of pregnancy and motherhood among teenage mothers in a suburb of Accra, Ghana: a qualitative study. Int J Women’s Health. 2013;5:773–80. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S51528.

Kaufman CE, De Wet T, Stadler J. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in South Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(2):147–60.

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. “I have to provide for another life emotionally, physically and financially”: understanding pregnancy, motherhood and the future aspirations of adolescent mothers in KwaZulu-Natal South, Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):620. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03319-7.

Ntinda K, Thwala SLK, Dlamini TP. Lived experiences of school-going early mothers in Swaziland. J Psychol Afr. 2016;26(6):546–50.

Melvin AO, Uzoma UV. Adolescent mothers’ subjective well-being and mothering challenges in a Yoruba community, southwest Nigeria. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(6):552–67.

Mashala P, Esterhuizen R, Basson W, Nel K. Qualitative exploration of the experiences and challenges of adolescents during pregnancy. J Psychol Afr. 2012;22(1):49–55.

Naidoo J, Muthukrishna N, Nkabinde R. The journey into motherhood and schooling: narratives of teenage mothers in the South African context. Int J Incl Educ. 2021;25(10):1125–39.

Dzotsi HT, Oppong Asante K, Osafo J. Challenges associated with teenage motherhood in Ghana: a qualitative study. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2020;15(1):85–96.

Amod Z, Halana V, Smith N. School-going teenage mothers in an under-resourced community: lived experiences and perceptions of support. J Youth Stud. 2019;22(9):1255–71.

Taffa N, Matthews Z. Teenage pregnancy experiences in rural Kenya. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2003;15(4):331–40.

Van Zyl L, van Der Merwe M, Chigeza S. Adolescents’ lived experiences of their pregnancy and parenting in a semi-rural community in the Western Cape. Soc Work. 2015;51(2):151–73.

Swartz S, Bhana A. Teenage tata: Voices of young fathers in South Africa. 2009.

Chideya Y, Williams F. Adolescent fathers: exploring their perceptions of their role as parent. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk. 2013;49(2).

Matlakala F, Makhubele J, Mashilo M. Challenges of teenage fathers towards fatherhood in Vaalbank, Mpumalanga province. Gender Behav. 2018;16(3):12013–20.

De Wet N, Amoo EO, Odimegwu C. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: where are the young men involved? S Afr J Child Health. 2018;2018(1):s44–50.

Shefer T, Bhana D, Morrell R. Teenage pregnancy and parenting at school in contemporary South African contexts: deconstructing school narratives and understanding policy implementation. Perspect Educ. 2013;31(1):1–10.

Ngabaza S, Shefer T. Policy commitments vs. lived realities of young pregnant women and mothers in school, Western Cape, South Africa. Reprod Health Matt. 2013;21(41):106–13.

Matlala SF, Nolte A, Temane M. Secondary school teachers’ experiences of teaching pregnant learners in Limpopo province, South Africa. S Afr J Educ. 2014;34(4):1.

Theron L, Dunn N. Coping strategies for adolescent birth-mothers who return to school following adoption. S Afr J Educ. 2006;26(4):491–9.

Chigona A, Chetty R. Girls’ education in South Africa: Special consideration to teen mothers as learners. Journal of education for international development. 2007.

Omwancha KM. The implementation of an educational re-entry policy for girls after teenage pregnancy: a case study of public secondary schools in the Kuria District, Kenya. 2012.

Ngabaza S. An exploratory study of experiences of parenting among a group of school-going adolescent mothers in a South African township. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape; 2010.

Simelane Q, Thwala S, Mamba T. An assessment of the implementation of the re-entry policy for girls in Swaziland: school practices and implications for policy development. Probl Educ 21st Century. 2013;56:115.

Runhare T, Mulaudzi O, Dzimiri P, Vandeyar S. Democratisation of formal schooling for pregnant teenagers in South Africa and Zimbabwe: smoke and mirrors in policy. Gender Behav. 2014;12(2):6382–95.

Nyariro MP. Re-conceptualizing school continuation & re-entry policy for young mothers living in an urban slum context in Nairobi, Kenya: a participatory approach. Stud Soc Justice. 2018;12(2):310–28.

Mwanza MN. Factors that influence the use of the education re-entry policy for adolescent mothers in Monze, Zambia. 2018.

Maluli1 F, Bali T. Exploring experiences of pregnant and mothering secondary school students in Tanzania. 2014.

Walgwe EL, LaChance NT, Birungi H, Undie C-C. Kenya: Helping adolescent mothers remain in school through strengthened implementation of school re-entry policies. 2016.

Zuilkowski SS, Henning M, Zulu J, Matafwali B. Zambia’s school re-entry policy for adolescent mothers: examining impacts beyond re-enrollment. Int J Educ Dev. 2019;64:1–7.

Tarus CBK. The level of awareness of re–entry policy of teenage mothers in public secondary schools in Kenya. Am J Humanit Soc Sci Res. 2020;4(2):249–63.

Mbugua NW. Stakeholders’roles in implementing the readmission policy on adolescent mothers in public secondary schools in Kikuyu District, Kiambu County, Kenya. Kenya: The Catholic University of Eastern Africa; 2015.

Birungi H, Undie C-C, MacKenzie I, Katahoire A, Obare F, Machawira P. Education sector response to early and unintended pregnancy: A review of country experiences in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2015.

Shaningwa LM. The educationally-related challenges faced by teenage mothers on returning to school: a Namibian case study. Grahamstown: Rhodes University; 2007.

McCadden DT. An Assessment of the Impact of Zambia’s School Re-Entry Policy on Female Educational Attainment and Adolescent Fertility. Washington: Georgetown University; 2015.

Jochim J, Groves A, Cluver L. When do adolescent mothers return to school? Timing across rural and urban South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(9):850–4.

Bhana D, Morrell R, Shefer T, Ngabaza S. South African teachers’ responses to teenage pregnancy and teenage mothers in schools. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(8):871–83.

Nelima WA. Bending the private-public gender norms: negotiating schooling for young mothers from low-income households in Kenya. Hague: International Institute of Social Studies; 2011.

Madhavan S, Thomas KJ. Childbearing and schooling: New evidence from South Africa. Comp Educ Rev. 2005;49(4):452–67.

Achoka JS, Njeru FM. De-stigmatizing teenage motherhood: towards achievement of universal basic education in Kenya. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(6):887–92.

Bhana D, Clowes L, Morrell R, Shefer T. Pregnant girls and young parents in South African schools. Agenda. 2008;22(76):78–90.

Chilisa B. National policies on pregnancy in education systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Botswana. Gend Educ. 2002;14(1):21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250120098852.

Grant MJ, Hallman KK. Pregnancy-related school dropout and prior school performance in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(4):369–82.

Malahlela MK, Chireshe R. Educators’ perceptions of the effects of teenage pregnancy on the behaviour of the learners in South African secondary schools: implications for teacher training. J Soc Sci. 2013;37(2):137–48.

Maputle M, Lebese R, Khoza L. Perceived challenges faced by mothers of pregnant teenagers who are attending a particular school in Mopani District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int J Educ Sci. 2015;10(1):142–8.

Mashishi N, Makoelle T. Inclusion or exclusion ramifications of teenage pregnancy: a comparative analysis of Namibia and South African Schools Pregnancy Policies. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2014;5(14):374.

Matshotyana Z. Experiences of parenting learners with regards to learner pregnancy policy. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape; 2010.

Mcambi SJ. Exploring young women's experiences of teenage motherhood in schools: a gendered perspective 2010.

Nkabinde RN. The geographies of schooling and motherhood: narratives of teen mothers in KwaZulu-Natal 2014.

Nkani FN, Bhana D. No to bulging stomachs: male principals talk about teenage pregnancy at schools in Inanda. Durban Agenda. 2010;24(83):107–13.

Pillay N. Pathways to school completion for young mothers: are we winning the fight? South Afr J Child Health. 2018;2018(1):s15–8.

Jumba LK, Githinji F. School factors which enhance the schooling of teen mothers in secondary school in Kenya: a Case of Trans-Nzoia West Sub-County. J Art Soc Sci. 2018;2(1).

Mwanza MN. Factors that influence the use of the education re-entry policy for adolescent mothers in Monze, Zambia. The Hague: International Institute of Social Studies; 2018.

Kola L, Abiona D, Adefolarin AO, Ben-Zeev D. Mobile phone use and acceptability for the delivery of mental health information among perinatal adolescents in nigeria: survey study. JMIR Mental Health. 2021;8(1): e20314.

Muyama DL, Musaba MW, Opito R, Soita DJ, Wandabwa JN, Amongin D. Determinants of postpartum contraception use among teenage mothers in Eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Open Access J Contracept. 2020;11:187.

Musyimi CW, Mutiso VN, Nyamai DN, Ebuenyi I, Ndetei DM. Suicidal behavior risks during adolescent pregnancy in a low-resource setting: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7): e0236269.

Laurenzi CA, Gordon S, Abrahams N, du Toit S, Bradshaw M, Brand A, et al. Psychosocial interventions targeting mental health in pregnant adolescents and adolescent parents: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2020;17:1–15.

Kola L, Bennett IM, Bhat A, Ayinde OO, Oladeji BD, Abiona D, et al. Stigma and utilization of treatment for adolescent perinatal depression in Ibadan Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–8.

Field S, Honikman S, Abrahams Z. Adolescent mothers: a qualitative study on barriers and facilitators to mental health in a low-resource setting in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):1–9.

Mbawa M, Vidmar J, Chingwaru C, Chingwaru W. Understanding postpartum depression in adolescent mothers in Mashonaland Central and Bulawayo Provinces of Zimbabwe. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;32:147–50.

Kaye DK. Negotiating the transition from adolescence to motherhood: coping with prenatal and parenting stress in teenage mothers in Mulago hospital, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):1–6.

BeLue R, Schreiner AS, Taylor-Richardson K, Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. What matters most: an investigation of predictors of perceived stress among young mothers in Khayelitsha. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(6):638–48.

Yako E. A comparative study of adoloscents’ perceived stress and health outcomes among adolescent mothers and their infants in Lesotho. Curationis. 2007;30(1):15–25.

Kimbui E, Kuria M, Yator O, Kumar M. A cross-sectional study of depression with comorbid substance use dependency in pregnant adolescents from an informal settlement of Nairobi: drawing implications for treatment and prevention work. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):1–15.

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. Antenatal and postpartum depression: prevalence and associated risk factors among adolescents’ in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Depression Res Treat. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5364521.

Osok J, Kigamwa P, Vander Stoep A, Huang K-Y, Kumar M. Depression and its psychosocial risk factors in pregnant Kenyan adolescents: a cross-sectional study in a community health Centre of Nairobi. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–10.

Niyonsenga J, Mutabaruka J. Factors of postpartum depression among teen mothers in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosomatic Obstet Gynecol. 2020;42:356.

Mokwena JP, Govender S, Setwaba MB. Health and well-being among teenage mothers in a rural South African community. J Psychol Afr. 2016;26(5):428–31.

Sodi EE. Psychological impact of teenage pregnancy on pregnant teenagers 2010.

Govender D, Taylor M, Naidoo S. Adolescent pregnancy and parenting: perceptions of healthcare providers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1607.

Ruzibiza Y. ‘They are a shame to the community…’stigma, school attendance, solitude and resilience among pregnant teenagers and teenage mothers in Mahama refugee camp, Rwanda. Glob Public Health. 2020;16:763.

Kululanga LI, Kadango A, Lungu G, Jere D, Ngwale M, Kumbani LC. Knowledge deficit on health promotion activities during pregnancy: the case for adolescent pregnant women at Chiladzulu District, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Annika J, Kirumira EK, Faxelid E. Seeking safety and empathy: adolescent health seeking behavior during pregnancy and early motherhood in central Uganda. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):781–96.

Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Annika J, Kirumira EK, Faxelid E. Adolescent and adult first time mothers’ health seeking practices during pregnancy and early motherhood in Wakiso district, central Uganda. Reprod Health. 2008;5(1):1–11.

Twintoh RF, Anku PJ, Amu H, Darteh EKM, Korsah KK. Childcare practices among teenage mothers in Ghana: a qualitative study using the ecological systems theory. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Pillay N. ‘There is no more future for me? Like really, are you kidding?’: agency and decision-making in early motherhood in an urban area in Johannesburg, South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):1886456.

Kabwijamu L, Waiswa P, Kawooya V, Nalwadda CK, Okuga M, Nabiwemba EL. Newborn care practices among adolescent mothers in Hoima District, Western Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11): e0166405.

Naidoo S, Taylor M, Govender D. Nurses’ perception of the multidisciplinary team approach of care for adolescent mothers and their children in Ugu, KwaZulu-Natal. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2019;11(1):1–11.

Mngadi PT. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in Swaziland: quality of care, community support and health care service needs: Institutionen för folkhälsovetenskap/Department of Public Health Sciences; 2006.

Yeboah M. Social support and access to prenatal health services: a study of pregnant teenagers in Cape Coast, Ghana. J Sci Technol. 2012;32(1):68–78.

Adonis T. Family planning among teenage mother in a cameroonian centre. Afr J Reprod Health. 2001;5(2):105.

Ehlers V. Adolescent mothers’ knowledge and perceptions of contraceptives in Tshwane, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2003;8(1):13–25.

Ehlers VJ. Adolescent mothers’ utilization of contraceptive services in South Africa. Int Nurs Rev. 2003;50(4):229–41.

Olaseha I, Ajuwon A, Onyejekwe O. Reproductive health knowledge and use of contraceptives among adolescent mothers in a sub-urban community in Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33(2):139–43.

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. “My partner was not fond of using condoms and I was not on contraception”: understanding adolescent mothers’ perspectives of sexual risk behaviour in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–17.

Machira K, Palamuleni ME. Health care factors influencing teen mothers’ use of contraceptives in Malawi, Ghana. Med J. 2017;51(2):88–93.

Mphatswe W, Maise H, Sebitloane M. Prevalence of repeat pregnancies and associated factors among teenagers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(2):152–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.09.028. (Epub 2016/03/08).

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. Scoping review of risk factors of and interventions for adolescent repeat pregnancies: a public health perspective. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):e1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1685. (Epub 2018/06/27).

Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. Prevalence and risk factors of repeat pregnancy among South African adolescent females. Afr J Reprod Health. 2019;23(1):73–87.

Dzabala N, Kachingwe M, Chikowe I, Chidandale C, van der Haar L. Using evidence and data to design an intervention in the Project Community Model for fostering health and wellbeing among adolescent mothers and their children. Front Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.584575.

Ndirangu G, Gichangi A, Kanyuuru L, Otai J, Mulindi R, Lynam P, et al. Using young mothers’ clubs to improve knowledge of postpartum hemorrhage and family planning in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. J Commun Health. 2015;40(4):692–8.

Robertson AE, Crowley T. Adolescent mothers’ lived experiences whilst providing continuous kangaroo mother care: a qualitative study. Health SA Gesondheid. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v25i0.1450. (Epub 2020-01-20).

Leerlooijer JN, Bos AER, Ruiter RAC, van Reeuwijk MAJ, Rijsdijk LE, Nshakira N, et al. Qualitative evaluation of the Teenage Mothers Project in Uganda: a community-based empowerment intervention for unmarried teenage mothers. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):816. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-816.

Leerlooijer JN, Kok G, Weyusya J, Bos AER, Ruiter RAC, Rijsdijk LE, et al. Applying Intervention Mapping to develop a community-based intervention aimed at improved psychological and social well-being of unmarried teenage mothers in Uganda. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(4):598–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyu020.

Ministry of Education Republic of Kenya. National Guidelines for school re-entry in Early Learning and Basic Education, 220. Nairobi: Ministry of Education; 2021.

Ajayi AI, Otukpa EO, Mwoka M, Kabiru CW, Ushie BA. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health research in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of substantive focus, research volume, geographic distribution and Africa-led inquiry. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(2): e004129. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004129.

Funding

This research was made possible through funding to the African Population and Health Research Center from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency for the Challenging the Politics of Social Exclusion project (Sida Contribution No. 12103). CK’s writing time was partially covered by a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) for the Action to empower adolescent mothers in Burkina Faso and Malawi to improve their sexual and reproductive health project (Grant No. 109813 – 001). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors or Sida.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AIA and CWK conceptualized the study. AIA, SA, and WM conducted the search and data extraction. All authors contributed to drafting and reviewing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not obtained for this study because it is based on a review of publicly available articles and does not involve human subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Sample search terms.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ajayi, A.I., Athero, S., Muga, W. et al. Lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa: A scoping review. Reprod Health 20, 113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01654-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01654-4