Abstract

Background

Women’s sexual health is generally defined and explored solely in relation to reproductive capacity, and often omits elements of sexual function and/or dysfunction. Concerted focus is given to women’s health during pregnancy; however, women’s sexual health is largely neglected after childbirth. This scoping review explored how the sexual health of postpartum women has been defined, measured, and researched in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

Articles eligible for review were those that investigated women’s sexual health during the first 12 months postpartum and were conducted among women aged 15–49 in LMICs. Eligibility was further restricted to studies that were published within the last 20 years (2001–2021). The initial PubMed search identified 812 articles, but upon further eligibility review, 97 remained. At this time, the decision was made to focus this review only on articles addressing sexual function and/or dysfunction, which yielded 46 articles. Key article characteristics were described and analyzed by outcome.

Results

Of the final included articles, five studies focused on positive sexual health, 13 on negative sexual health, and the remaining 28 on both positive and negative sexual health or without specified directionality. The most common outcome examined was resumption of sex after childbirth. Most studies occurred within sub-Saharan Africa (n = 27), with geographic spread throughout the Middle East (n = 10), Asia (n = 5), North Africa (n = 3), and cross-geography (n = 1); notably, all five studies on positive sexual health were conducted in Iran. Negative sexual health outcomes included vaginismus, dyspareunia, episiotomy, perineal tears, prolapse, infection, obstetric fistula, female genital cutting, postnatal pain, uterine prolapse, coercion to resume sex, sexual violence, and loss of sexual desire/arousal. Most studies were quantitative, though eight qualitative studies elucidated the difficulties women endured in receiving information specific to sexual health and hesitance in seeking help for sexual morbidities in the postpartum period.

Conclusions

Overall, the evidence base surrounding women’s sexual health in the postpartum period within LMICs remains limited, with most studies focusing solely on the timing of resumption of sex. Integration of sexual health counseling into postnatal care and nonjudgmental service provision can help women navigate these bodily changes and ultimately improve their sexual health.

Plain language summary

Women’s sexual health is often studied in relation to reproductive health and childbearing. While reproductive health during pregnancy and immediately after is well documented, it remains unclear how women’s sexual health is addressed, particularly within low- and middle-income countries. The aim of this review is to understand how researchers have measured, defined, and examined postpartum sexual health. In October 2021, we searched PubMed database with the following criteria: published in the last 20 years; conducted in a low- or middle-income context; examined sexual function and/or dysfunction among women aged 15–49 within 1 year after childbirth. From this inclusion criteria, we identified 46 relevant articles. Most studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. Only five studies focused exclusively on positive sexual health, and the majority of studies examined the resumption of sex after childbirth. Multiple qualitative studies described women’s reluctance to seek help for postpartum sexual health issues and highlighted the difficulties they faced in receiving information specific to sexual health. Overall, the evidence base surrounding women’s sexual health after childbirth within low- and middle-income contexts is limited. Future research should examine sexual health beyond resumption of sex after childbirth and explore barriers to help-seeking for women experiencing sexual health issues. Further exploration of positive sexual health is needed across contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Women’s health is often framed in relation to reproductive capacity, with less attention on the wide spectrum of health outcomes that are both unique to women or disproportionately impact women [1, 2]. The sexual and reproductive health (SRH) field has been largely criticized for underemphasis on the “S” in SRH, where these critiques highlight underinvestment in and lack of policies surrounding women’s sexual health [3, 4]. Sexual health, or “the positive and respectful approach to sexual relationships, including pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free from coercion, discrimination, or violence” [5], is a cornerstone of Sustainable Development Goal-5 [6], however, indicators notably center around infringements on sexual rights, including sexual violence, child marriage, and female genital cutting (FGC), rather than addressing positive outcomes, such as voluntary resumption of sex or sexual pleasure.

Pregnancy and childbirth are profound physical and psychological transition periods for women, and vast literature has documented the impact of pregnancy on women’s sexual health, including the necessity of sexual health counseling during antenatal care visits and childbirth classes [7, 8]. Further, a number of studies from high-income countries, including systematic reviews, have explored specific sexual function or dysfunction outcomes during the postpartum period [9,10,11]. These studies reveal the high prevalence of sexual morbidities, such as dyspareunia, incontinence, lack of desire, and change in sensations of pleasures following childbirth, as well need for effective interventions and counseling strategies to navigate them [9,10,11]. Additionally, the effects of psychological changes within the postpartum period must be considered, as postnatal depression affects as many as one in five women and can have a profound impact on sexual desire and the perception of sexual pleasure [7]. Despite the research supporting interventions, postpartum sexual health care remains regionalized, under-funded, and without policy support, even within high-income countries.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many women deliver at home or in facilities that are ill-equipped for obstetric emergencies [12], placing them at increased risk of both short- and long-term delivery complications [13, 14], including sexual health morbidities [15]. Antenatal and postnatal care are key intervention points for sexual health education and counseling; however, coverage of these services varies substantially, both within and across LMIC contexts [7, 16, 17] Moreover, recent efforts to estimate the coverage of quality services have found substantial gaps [16, 17]. Postnatal care, which consistently has lower coverage than antenatal care [18, 19], focuses largely on life-threatening danger signs to the child, with maternal health often limited to counseling on postpartum contraceptive use to prevent short interval pregnancies. Given these gaps in care, much less is known about the prevalence of postpartum sexual health complications and/or practices to mitigate dysfunctions and promote positive sexual health within LMICs.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to synthesize the current literature on women’s sexual health in the postpartum period, with a focus on research specific to sexual function and dysfunction among women living in LMICs. Findings can inform research and practice guidelines within LMICs.

Methods

Scoping review procedures

A scoping review was conducted to identify and summarize studies from LMICs, as described by Arksey and Malley [20], Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien [21], and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews [22]. First, a search strategy was developed with the assistance of library informationists (Additional file 1: Table S1). This search was conducted within PubMed in October 26, 2021, with identified references imported into Covidence, a systematic literature review management program. Titles and abstracts of each reference were screened by one Masters-level researcher, with questions flagged for the first author. Full-text articles were then reviewed by two Masters-level researchers to determine final eligibility. Throughout the review process, eligibility criteria were discussed with the entire authorship team and any disputes resolved via discussion. All decisions were documented within Covidence software.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were peer-reviewed, English-language articles, published within the past twenty years (2001 to 2021), and explored women’s sexual health in the postpartum period. Initially, the team adopted a broad definition of sexual health—in line with the World Health Organization’s definition and examples—which included wide-ranging topics such as sexual expression, relationships, pleasure, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), sexual dysfunction, sexual violence, and harmful sexual practices [23]. Given the vast, well-documented literature on postpartum contraception, family planning, and return to fertility, the team chose to not include these terms within the search. During the full-text review of the literature, the team identified 97 articles that met the initial review criteria; of note, this initial review included topics such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), reproductive cancers, fistula, reproductive tract infections (RTIs), uterine prolapse, FGC, sexual violence, sexual function, and sexual dysfunction. To allow for a more focused discussion while ensuring comprehensive coverage of positive and negative sexual health outcomes, the research team chose to narrow the inclusion criteria and focus solely on sexual function and/or dysfunction (defined further below); many of the initial topics were also included if the article concurrently discussed sexual function/dysfunction. Future work aims to explore the myriad of additional sexual health needs of women in the postpartum period.

Final inclusion criteria:

-

Studies that examined women’s sexual health during the postpartum period.

-

For the purpose of this scoping review, the postpartum period was defined as one year after delivery.

-

To allow for a comprehensive lens of sexual health and be in line with the World Health Organization's definition, sexual health included both negative and positive experiences; this review focuses on sexual function (including resumption of sexual activity, sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, arousal, intimacy, orgasm) and sexual dysfunction (including dyspareunia, sexual violence, sexual coercion)

-

-

Studies focused on women of childbearing age (ages 15–49)

-

Studies published in English

-

Studies conducted in low or low-middle economies, as defined by the World Bank lending groups (2021–2022 classification)

-

Studies published within the last 20 years (between 2001 and 2021)

Final exclusion criteria

-

Studies that were not conducted with women less than one year postpartum (i.e., studies with only male partners or service providers)

-

Studies not specific to sexual health, and specifically sexual function/dysfunction, as defined within the inclusion criteria

-

Studies specific to rapid repeat pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, abortion, postpartum family planning, contraceptive side-effects, or postpartum fertility, including studies that examined sexual abstinence only in relation to fertility and family planning

-

Literature reviews, case reports, study protocols, and grey literature

-

Studies focused on morbidities experienced before or after, rather than during, the postpartum period

-

Studies that focused on the perspectives of men and men’s sexual activity within the postpartum period

-

Studies that focus on highly specific subgroups, such as HIV positive women only

Data extraction

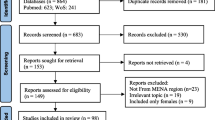

The search yielded 812 results, all of which were screened via title and abstract review. Of these, 241 progressed to a full-text review. Based on the initially broad inclusion criteria, 97 articles were eligible for inclusion. After further restricting the inclusion criteria to only studies involving sexual function and/or dysfunction, only 46 articles were eligible and included (Fig. 1). Key characteristics of each article (author, year, objective, population, study design, sexual health topic, results) were described in Microsoft Excel tables by two Masters-level researchers and consolidated with input by the lead author; extracted data and study characteristics were then analyzed by positive sexual health (i.e., sexual function), negative sexual health (i.e., sexual dysfunction), and studies that reported both positive and negative sexual health or approached sexual health from a neutral perspective, which often examined resumption of sex as an outcome without indication of whether this outcome was viewed positively or negatively.

Results

The final inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded 46 articles (Tables 1, 2, 3). Of these 46 articles, five studies focused on positive sexual health, 13 studies on negative sexual health, and the remaining 28 on both positive and negative sexual health or without specified directionality. The most common outcome examined was resumption of sex after childbirth. The majority of studies occurred within sub-Saharan Africa (n = 27), with additional geographic spread throughout the Middle East (n = 10), Asia (n = 5), and North Africa (n = 3); one study analyzed data from 17 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) [24]. Most studies were quantitative, including prospective cohort, cross-sectional, and clinical trial designs; however, eight studies solely or supplementally collected qualitative data.

Positive sexual health

Five studies examined positive sexual health during the postpartum period with outcomes including libido, satisfaction, stimulation, orgasm, pelvic floor muscle strength, sexual self-efficacy, female sexual function (measured via the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)), and intimacy [25,26,27,28,29] (Table 1). Notably, all five studies were conducted within the Islamic Republic of Iran and largely within the context of interventions or utilizing comparison groups. Specifically, Golmakani et al. examined the impact of a pelvic floor muscle exercise program on pelvic floor strength and sexual self-efficacy and found significant increases in both outcomes within the intervention compared to the control group [26]. Zamani et al. examined the effectiveness of sexual health counseling and found increased sexual satisfaction among intervention participants [29]. Two additional studies examined sexual function in relation to infant feeding practices, with mixed results [25, 27]. Additionally, Nezhad and Goodarzi examined intimacy and sexuality within the context of partnerships and found that having a high level of intimacy could potentially buffer against negative effects of low sexual satisfaction on overall marital satisfaction [28].

Negative sexual health

Thirteen studies explored negative sexual health outcomes, including vaginismus, dyspareunia, episiotomy, perineal tears, prolapse, infection, obstetric fistula, female genital cutting, postnatal pain, uterine prolapse, coercion to resume sex, sexual violence, and loss of sexual desire/arousal [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] (Table 2).

Dyspareunia, or painful intercourse, was one of the most examined negative sexual health outcomes for postpartum women. In Nigeria, Adanikin found that over one in three women reported dyspareunia within six months after delivery [31]. Similarly, in Ethiopia, approximately one in five women reported sexual morbidities upon resuming intercourse in the postpartum period, and dyspareunia was the most common morbidity reported [37]. In Pakistan, dyspareunia was examined in relation to episiotomy, where dyspareunia was more prevalent among episiotomy patients than those without (69% vs. 12%) [36]. Further, in Nigeria, Oboro and Tabowei found that painful intercourse decreased throughout the postpartum period, with approximately 55% of women reporting painful intercourse at 6-weeks postpartum and dropping to less than 20% at 6-months postpartum; dyspareunia at 3-months postpartum was significantly more likely among women who had perineal trauma or reported pre-pregnancy dyspareunia [40].

Resumption of sex, if explored in relation to coercive or forced sex, was also included within negative sexual health outcomes. Postpartum sexual abstinence was largely practiced across settings (though length of time depended on cultural factors); however, not all women who resumed sex did so on their own accord. Specifically, in Ethiopia, among the 20% of women who had resumed sex within 6-weeks postpartum (and prior to the end of the 40 day sexual abstinence period largely observed within Ethiopia), half reported being pressured by their husband to resume intercourse [37].

While our search only uncovered three qualitative studies specific to negative sexual health, these studies were helpful for elucidating cultural beliefs and concerns surrounding sexual health in the postpartum period. In Cambodia, White explored Khmer women’s beliefs surrounding sex, specifically that resuming sex too soon after delivery, either by choice or by force, could cause physical health symptoms [42]. In Mozambique, women with fistula reported no sexual activity since onset, with one woman reporting that her husband had used her “handicap” to justify taking an additional wife [33].

Across studies/settings, many women reported sexual health morbidities following pregnancy and childbirth, however, help-seeking or participation within interventions was minimal. In Tunisia, Achour et al. reported that while women experienced vaginismus symptoms following delivery, 60% did not feel that sex was important compared to motherhood, and no women completed the pelvic floor training program nor sought counseling from the sexologist [30]. Moreover, some studies reported that women did not feel comfortable discussing sexual health issues or felt providers were poorly equipped to handle matters surrounding sexual health. In Nigeria, while 98% of women in the study reported receiving counseling on contraception, only 29% reported discussions surrounding sexual health [40]. Similarly, in Iran, women felt their sexual health needs during the postpartum period were often neglected by healthcare providers [39].

Additional findings included associations between RTIs and uterine prolapse and postpartum depression [41], a cross-sectional examination of abnormal vaginal discharges in Zambian women [38], perineal tearing and postpartum complications related to FGC in Ethiopia [35], and perineal tearing and genital prolapse in Bangladesh [34].

Positive and negative (or neutral) sexual health

Studies that examined both positive and negative sexual health outcomes or examined women’s health within the postpartum period from a neutral perspective are outlined within Table 3 [24, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] (n = 28). Of note, the majority of studies within this group explore prevalence or corelates of resumption of sex, with little discussion of the positive or negative impact of the timing of sexual activity within the postpartum period [24, 43, 46, 48,49,50, 53, 54, 58, 61, 66, 67]. In a multi-country DHS study, resumption of sex was related to the return of a woman’s menses [24], and this practice was corroborated via qualitative data from Cote d’Ivoire [47] and Malawi [68]. In Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Eswatini, and Malawi, postpartum sexual abstinence was further described in relation to breastfeeding or child developmental benchmarks, specifically the child being of age to walk [47, 56, 63, 68].

Multiple studies linked resumption of sexual activity to their husband’s sexual needs or demands [44, 52, 55, 57, 63]. A qualitative study in Cote d’Ivoire depicted this pressure on women to resume sex—while some women felt that polygynous marriages were useful in allowing for long abstinence periods, others expressed fear of infidelity and related STI risks [47]. In one study from Kenya, increased odds of resumption of sex was associated with past-month forced sex [53].

Few studies explored specific cultural practices, withstanding timing of resumption of sex, in relation to women’s sexual health. In northern Nigeria, women reported a number of postpartum practices, including postpartum abstinence periods inclusive of confinement for 40 days after birth or longer, hot ritual baths, nursing in heated rooms, laying on heated beds, and consuming specific foods [51]. In Malawi, substantial regional variation persisted in cultural practices, however, need for postpartum abstinence was described in relation to healing the mother, partner, and child, with early resumption linked to numerous health complications [68].

Notably, within qualitative data, women described feeling less sexually attractive during the postpartum period and felt that decreased self-confidence impacted their sexual health and desire; however, they also indicated that partner acceptance of their body changes helped improve their anxiety surrounding sex [45]. Some women simply stated that they were too tired to engage in sex [54].

Within the studies on both negative and positive sexual health, women similarly reported difficulty seeking help or discussing sex with healthcare providers [44]. In one Nigerian study, fewer than two thirds of postpartum women sought help for the sexual morbidities they were experiencing, and prominent reasons for not seeking health included feeling shy, the problem resolving on its own, cultural or religious factors, and not having a female doctor to ask [52]. In Tanzania, women described that too much health education was provided at once during antenatal care, and felt that some of this information should be spread throughout postpartum care visits [56]. In Uganda, women noted that the advice provided by health workers at discharge was inconsistent, leaving them unsure of when to resume sexual activity and how to navigate associated health and safety risks [60].

Discussion

While our search yielded 46 studies examining sexual health in the postpartum period within LMICs, only five of these studies focused exclusively on positive sexual health. Rather, sexual health was generally framed within the context of delivery complications (episiotomies, prolapse, fistula) or morbidities that continued into the postpartum period. Moreover, the vast majority of studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa—while this number of articles was nearly three-fold those from other geographies, many of these studies only examined the prevalence or correlates of sexual resumption. Overall, the evidence base surrounding women’s sexual health in the postpartum period within LMICs remains limited in comparison to higher income countries and highlights a need to explore a broader range of sexual health outcomes, including those surrounding positive sexual health.

This review highlights a clear need for increased sexual health education for postpartum women within LMICs. Prior global literature has highlighted a lack of education on positive sexual health, which is influenced by access to sexuality education, including knowledge of risks/vulnerabilities, access to sexual health care, and affirmative environments to promote positive sexual health [6]. Specifically, our results found that when women experienced sexual health morbidities within the postpartum period, they were hesitant to seek help from providers, both because they felt embarrassed and because they felt providers were poorly equipped to handle issues surrounding women’s sexual health. Further, many women were unclear about the recommended timing surrounding safe resumption of sex, and instead turned to cultural practices, which were largely enforced by family members. Sexual health education, including guidance surrounding care-seeking for potential sexual health morbidities that could occur, must be included within postnatal care services to ensure that women are able to resume sex when they feel the time is right for themselves and their relationships. Additionally, normalization of sexual health dysfunction, particularly at a time when women’s bodies are undergoing massive physical and hormonal changes, can help women feel less embarrassed and stigmatized. Clear guidelines for healthcare providers on how to integrate sexual health education into postpartum protocols are necessary, alongside the expansion of accessible postpartum care services far into the postpartum period given delays in resumption of sexual activity and recognition of associated dysfunctions.

While maternal health services are rapidly expanding within LMICs, attention is shifting to not only ensure provision of services, but to also assess the quality of such services [16]. Current quality of care assessments, however, do not include sexual health counseling and to date, the majority have focused on content of antenatal services, with little attention to quality of postnatal care services [69]. Without data to examine receipt and content of sexual health education and counseling as part of antenatal and/or postnatal care services, the research and practice field does not have a clear sense of when and how sexual health is addressed. Future work must seek to close this data gap given the profound impact these data will have on shaping clinical practice guidelines and in turn, monitoring quality of care.

Strengths of this study include a rigorously implemented scoping protocol, utilization of library informationists in developing and revising the search strategy, and focus on an understudied topic inclusive of both positive and negative sexual health outcomes; however, this study is not without limitations. Namely, this scoping review includes many studies with small samples or limited measures for sexual health in the postpartum period. The majority of studies included were cross-sectional in nature, limiting conclusions surrounding temporality of associations. Further, some studies did not define inclusion criteria surrounding timing within postpartum period, and thus were not included within the current scoping review as we could not assess whether the findings were specific to one year postpartum. Methodologic rigor was not assessed as part of this review given the large number of articles retained within our final criteria. Lastly, as our search strategy purposively did not examine women’s sexual health in relation to fertility and contraception, it is possible that some articles which also explored women’s sexual health in the postpartum period more broadly may have been missed by our search.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we urge future research to examine sexual health beyond the resumption of sex after childbirth and to explore barriers to help-seeking for women experiencing sexual health morbidities in the postpartum period. Further exploration of positive women’s sexual health is needed, inclusive of factors that may promote positive sexual health within the postpartum period. Ultimately, both the expansion of indicators surrounding positive sexual health and prioritization of women’s sexual health within global development priorities, such as the SDGs, can ensure that the full range of women’s health needs are not only addressed, but also valued, regardless of context.

Availability of data and materials

Original articles reviewed in this manuscript are available on PubMed.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

- FGC:

-

Female genital cutting

- FSFI:

-

Female Sexual Function Index

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income country

- RTI:

-

Reproductive tract infection

- SRH:

-

Sexual and reproductive health

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

References

Strobino DM, Grason H, Minkovitz C. Charting a course for the future of women’s health in the United States: concepts, findings and recommendations. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(5):839–48.

Editorial L. Women: more than mothers. Lancet. 2007;370:1283.

Gruskin S, Yadav V, Castellanos-Usigli A, Khizanishvili G, Kismödi E. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2019;27(1):29–40.

Gilby L, Koivusalo M, Atkins S, Atkins S. Global health without sexual and reproductive health and rights? Analysis of United Nations documents and country statements, 2014–2019. BMJ Glob Heal. 2021;6(3):1–10.

World Health Organization (WHO). Definining Sexual Health. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

UNFPA. Measuring SDG Target 5.6: ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. New York: UNFPA; 2020.

Johnson CE. Sexual Health during Pregnancy and the Postpartum (CME). J Sex Med. 2011;8(5):1267–84.

Allen L, Fountain L. Addressing sexuality and pregnancy in childbirth education classes. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16(1):32–6.

Fan D, Li S, Wang W, Tian G, Liu L, Wu S, et al. Sexual dysfunction and mode of delivery in Chinese primiparous women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2017;17(1):408.

Cattani L, De Maeyer L De, Yerbakel J, Bosteels J, Deprest J. Predictors for sexual dysfunction in the first year postpartum: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;Online ahe.

Grussu P, Vicini B, Quatraro RM. Sexuality in the perinatal period: a systematic review of reviews and recommendations for practice. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021;30:100668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100668.

Campbell OMR, Graham WJ. Maternal Survival 2 Strategies for reducing maternal mortality : getting on with. Lancet. 2006;368.

Gon G, Leite A, Calvert C, Woodd S, Graham WJ, Filippi V. The frequency of maternal morbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;141(Supplement 1):20–38.

Koblinsky M, Chowdhury ME, Moran A, Ronsmans C. Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: neglected agenda in maternal health. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(2):124–30.

Hardee K, Gay J, Blanc AK. Maternal morbidity : Neglected dimension of safe motherhood in the developing world. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(6):603–17.

Arroyave L, Saad GE, Victora CG, Barros AJD. Inequalities in antenatal care coverage and quality: an analysis from 63 low and middle-income countries using the ANCq content-qualified coverage indicator. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(102):1–10.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Maeve O, Campbell R. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low- income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(e000779):1–11.

Amouzou A, Aguirre LC, Khan SM, Sitrin D, Vaz L. Measuring postnatal care contacts for mothers and newborns: an analysis of data from the MICS and DHS surveys. J Glob Health. 2017;7:2.

Sacks E, Langlois EV. Postnatal care: increasing coverage, equity, and quality. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e442-443.

Arksey H, Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, Brien KKO, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR ): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med Res Report Methods. 2016;2018(169):467–73.

World Health Organization. Sexual Health. 2021.

Borda MR, Winfrey W, McKaig C. Return to sexual activity and modern family planning use in the extended postpartum period: an analysis of findings from seventeen countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14:72–9.

Anharan ZK, Baghdari N, Pourshirazi M, Karimi FZ, Rezvanifard M, Mazlom SR. Postpartum sexual function in women and infant feeding methods. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(3):1–7.

Zare Z, Golmakani N, Khadem N, Shareh H, Shakeri MT. The effect of pelvic floor muscle exercises on sexual quality of life and marital satisfaction in primiparous women after childbirth. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2015;20(3):347–53.

Mirzaei N, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Bahri Khomami M, Moini A, Kazemnejad A. Sexual function, mental health, and quality of life under strain of COVID-19 pandemic in Iranian pregnant and lactating women: a comparative cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(66):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01720-0.

Nezhad MZ, Goodarzi AM. Sexuality, intimacy, and marital satisfaction in Iranian first-time parents. J Sex Marital Ther. 2011;37(2):77–88.

Zamani M, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Moradi M, Esmaily H. The effect of sexual health counseling on women’s sexual satisfaction in postpartum period: A randomized clinical trial. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019;17(1):41–50.

Achour R, Koch M, Zgueb Y, Ouali U, Hmid R. Vaginismus and pregnancy: Epidemiological profile and management difficulties. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:137–43.

Adanikin AI, Awoleke JO, Adeyiolu A, Alao O, Adanikin PO. Resumption of intercourse after childbirth in southwest Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care. 2015;20(4):241–8.

Assarag B, Dubourg D, Maaroufi A, Dujardin B, De Brouwere V. Maternal postpartum morbidity in Marrakech: what women feel what doctors diagnose? BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2013;13:1–16.

Boene H, Mocumbi S, Högberg U, Hanson C, Valá A, Bergström A, et al. Obstetric fistula in southern Mozambique: a qualitative study on women’s experiences of care pregnancy, delivery and post-partum. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):1–24.

Ahmed FA, Dasgupta SK, Jahan M, Huda FA, Ronsmans C, Chowdhury ME. Occurrence and determinants of postpartum maternal morbidities and disabilities among women in Matlab, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(2):143–58.

Gudu W, Abdulahi M. Labor, delivery and postpartum complications in nulliparous women with female genital mutilation admitted to Karamara Hospital. Ethiop Jedical J. 2017;55(1):11–7.

Islam A, Hanif A, Ehsan A, Arif S, Niazi SK, Niazi AK. Morbidity from episiotomy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(6):696–701.

Jambola ET, Gelagay AA, Belew AK, Abajobir AA. Early resumption of sexual intercourse and its associated factors among postpartum women in western ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:381–91.

Lagro M, Liche A, Mumba T, Ntebeka R, van Roosmalen J. Postpartum health among rural Zambian women. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003;7(3):41–8.

Nazari S, Hajian S, Abbasi Z, Majd HA. Postpartum care promotion base on maternal education needs: a mixed study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10(July):1–6.

Oboro V, Tabowei T. Sexual function after childbirth in Nigerian women. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002;78(3):249–50.

Surkan PJ, Sakyi KS, Christian P, Mehra S, Labrique A, Ali H, et al. Risk of depressive symptoms associated with morbidity in postpartum women in rural Bangladesh. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(10):1890–900.

White PM. Heat, balance, humors, and ghosts: postpartum in Cambodia. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(2):179–94.

Alum AC, Kizza IB, Osingada CP, Katende G, Kaye DK. Factors associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse among postnatal women in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1–15.

Anzaku A, Mikah S. Postpartum resumption of sexual activity, sexual morbidity and use of modern contraceptives among Nigerian women in Jos. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(2):210–6.

Asadi M, Noroozi M, Alavi M. Exploring the experiences related to postpartum changes: perspectives of mothers and healthcare providers in Iran. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2021;21(7):1–31.

Dadabhai S, Makanani B, Hua N, Kawalazira R, Taulo F, Gadama L, et al. Resumption of postpartum sexual activity and menses among HIV-infected women on lifelong antiretroviral treatment compared to HIV-uninfected women in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;149(2):211–8.

Desgrées-Du-Loû A, Brou H. Resumption of sexual relations following childbirth: norms, practices and reproductive health issues in Abidjan. Côte d’Ivoire Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13(25):155–63.

Ezebialu IU, Eke AC. Resumption of vaginal intercourse in the early postpartum period: determinants and considerations for child spacing in a Nigerian population. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2012;32(4):353–6.

Gadisa TB, Michael MW, Reda MM, Aboma BD. Early resumption of postpartum sexual intercourse and its associated risk factors among married postpartum women who visited public hospitals of Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–8.

Glynn JR, Buvé A, Caraël M, Macauley IB, Kahindo M, Musonda RM, et al. Research letters: Is long postpartum sexual abstinence a risk factor for HIV? AIDS. 2001;15(8):1059–61.

Iliyasu Z, Kabir M, Galadanci HS, Abubakar IS, Salihu HM, Aliyu MH. Postpartum beliefs and practices in Danbare village Northern Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2006;26(3):211–5.

Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Danlami KM, Salihu HM, Aliyu MH. Correlates of postpartum sexual activity and contraceptive use in Kano Northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22(1):103–12.

Kinuthia J, Richardson BA, Drake AL, Matemo D, Unger JA, McClelland RS, et al. Sexual behavior and vaginal practices during pregnancy and postpartum: implications for HIV prevention strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(2):142–9.

Lundberg PC, Thu TTN. Vietnamese women’s cultural beliefs and practices related to the postpartum period. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):731–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.02.006.

Maamri A, Badri T, Boujemla H, El KY. Sexuality during the postpartum period: study of a population of tunisian women. Tunis Med. 2019;97(5):704–10.

Mbekenga CK, Christensson K, Lugina HI, Olsson P. Joy, struggle and support: postpartum experiences of first-time mothers in a Tanzanian suburb. Women Birth. 2011;24(1):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2010.06.004.

Mekonnen BD. Factors associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse among women during extended postpartum period in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5(1):1–8.

Nkwabong E, Ilue EE, Nana NT. Factors associated with the resumption of sexual intercourse before the scheduled six-week postpartum visit. Trop Doct. 2019;49(4):260–4.

Nolens B, van den Akker T, Lule J, Twinomuhangi S, van Roosmalen J, Byamugisha J. Birthing experience and quality of life after vacuum delivery and second-stage caesarean section: a prospective cohort study in Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(8):914–22.

Odar E, Wandabwa J, Kiondo P. Sexual practices of women within six months of childbirth in Mulago hospital, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2003;3(3):117–23.

Osinde MO, Kaye DK, Kakire O. Influence of HIV infection on women’s resumption of sexual intercourse and use of contraception in the postpartum period in rural Uganda Michael. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;116(2):170–1.

Rezaei N, Azadi A, Sayehmiri K, Valizadeh R. Postpartum sexual functioning and its predicting factors among Iranian women. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24(1):94–103.

Shabangu Z, Madiba S. The role of culture in maintaining post-partum sexual abstinence of swazi women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):1–18.

Sheikhi ZP, Navidian A, Rigi M. Effect of sexual health education on sexual function and resumption of sexual intercourse after childbirth in primiparous women. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9(April):1–6.

Shirvani MA, Nesami MB, Bavand M. Maternal sexuality after child birth among Iranian women. Pak J Biol Sci. 2010;13(8):385–9.

Sule-Odu AO, Fakoya TA, Oluwole FA, Ogundahunsi OA, Olowu AO, Olanrewaju DM, et al. Postpartum sexual abstinence and breastfeeding pattern in Sagamu, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12(1):96–100.

Ugwu EO, Dim CC, Eleje GU. Effects of mode of delivery on sexual functions of parturients in Nigeria: a prospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(7):1925–33.

Zulu EM. Ethnic variations in observance and rationale for postpartum sexual abstinence in Malawi. Demography. 2001;38(4):467–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.050.

Arroyave L, Ghada E, Barros AJD. A new content-qualified antenatal care coverage indicator: development and validation of a score using national health surveys in low- and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04008.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Welch Medical Library informationists for their assistance in setting our scoping review search terms.

Funding

No funding to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SNW conceptualized the manuscript, guided inclusion exclusion/criteria, and drafted the manuscript. AP conducted the initial search, abstract/title review, and full text review, and compiled results tables. HLT conducted full text review and compiled results tables. CW and LAZ provided input into the eligibility criteria and scoping review process and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

PubMed MeSH Terms

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wood, S.N., Pigott, A., Thomas, H.L. et al. A scoping review on women’s sexual health in the postpartum period: opportunities for research and practice within low-and middle-income countries. Reprod Health 19, 112 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01399-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01399-6