Abstract

Background

The integration of family planning (FP) and HIV-related services is common in sub-Saharan Africa. Little research has examined how FP quality of care differs between integrated and non-integrated facilities. Using nationally representative data from Malawi and Tanzania, we examined how HIV integration was associated with FP quality of care.

Methods

Data were drawn from Service Provision Assessments (SPAs) from Malawi (2013–2014) and Tanzania (2014–2015). The analytic sample was restricted to lower-level facilities in Malawi (n = 305) and Tanzania (n = 750) that offered FP services. We matched SPA measures to FP quality of care indicators in the Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ). We conducted bivariate and multivariate analyses of 22 QIQ indicators to examine how integration status was related to individual QIQ indicators and overall FP quality of care at the facility- and client-level.

Results

The prevalence of HIV integration in Malawi (39%) and Tanzania (38%) was similar. Integration of HIV services was significantly associated (p < 0.05) with QIQ indicators in Malawi (n = 3) and Tanzania (n = 4). Except for one negative association in Tanzania, all other associations were positive. At the facility-level, HIV integration was associated with increased odds of being at or above the median in FP quality of care in Malawi (adjusted odd ratio (OR) = 2.24; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.32, 3.79) and Tanzania (adjusted OR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.37, 3.22). At the client-level, HIV integration was not associated with FP quality of care in either country.

Conclusion

Based on samples in Malawi and Tanzania, HIV integration appears to be beneficially associated with FP quality of care. Using a spectrum of FP quality of care indicators, we found little evidence to support concerns that HIV integration may strain facilities and providers, and adversely impact quality outcomes. Rather, it appears to strengthen FP service delivery by increasing the likelihood of stocked FP commodities and achievement of other facility-level quality indicators, potentially through HIV-related supply chains. Further research is needed to assess FP quality of care outcomes across the various platforms of FP integration found in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Integration of family planning (FP) and HIV-related services is a long-term trend in the health systems of sub-Saharan Africa [1]. While FP has been integrated with myriad other health services (e.g. maternal, neonatal, and child health services) [2], HIV-related services are a foremost platform of integration due to the prevalence of HIV and AIDS in the region [1]. We define service integration as the delivery of two different types of health services at the same facility, though various more precise definitions of integration are present in the literature [1, 3]. Integrated service delivery has grown more prevalent as research has accumulated on its potentially favorable effects, and as it has gained the support of local stakeholders [4].

The literature on FP and HIV service integration effects on facility-, provider-, and client-level outcomes is largely positive though inconclusive. Integration of FP and HIV services has been associated with beneficial clinical outcomes (e.g. prevention of unintended HIV-positive births) [5, 6], service delivery outcomes (e.g. improved service uptake) [7], and cost effectiveness (e.g. cost savings from infant HIV infections prevented) [1, 8]. However, the infrastructural and logistical challenges of integrating health services [4] has the potential to negatively affect base service quality [9] and dilute providers’ expertise [10].

Despite the predominance of integrated FP and HIV services, there is a paucity of research on how integrated programming may impact FP quality of care. The maintenance of FP quality of care is essential for positive client health outcomes and adherence to a reproductive rights-based approach to FP. The Bruce/Jain Quality of Care Framework, which has guided the design and delivery of services in the field of FP for over two decades, outlines six critical elements that constitute FP quality of care: choice of methods, information given to users, technical competence, interpersonal relations, follow-up or continuity mechanisms, and appropriate constellation of services [11]. The multidimensional nature of FP quality of care posited by the Bruce/Jain Framework necessitates measurement at the facility level (e.g. availability of FP methods), provider level (e.g. adherence to infection control guidelines), and client level (e.g. communication about client-preferred FP method) to sufficiently capture FP quality of care.

The few studies available on FP quality of care in HIV integrated facilities are limited by methodological concerns. In a review of integrated FP and HIV services globally, Spaulding and colleagues [12] identified four studies [13,14,15,16] reporting on “quality of services,” though most of this research is either drawn from grey literature with insufficiently detailed or weak study design [14,15,16] or reliant on provider-reported information such as knowledge and attitudes [16] as a proxy for FP quality of care. To gain a comprehensive understanding of FP quality of care, a theory-based measurement approach comprising indicators of quality at the facility, provider, and client level is needed for evidence-informed decision making.

The present study aimed to fill these knowledge gaps by using multiple objective indicators from a theory-based FP quality of care measurement tool, Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ), to assess the quality of FP care among HIV integrated and non-integrated facilities using Service Provision Assessment (SPA) data from Malawi (2013–2014) and Tanzania (2014–2015). Our specific objectives for this study were to investigate the level of FP quality of care in HIV integrated and non-integrated facilities, how FP quality of care compares between HIV integrated and non-integrated facilities, and finally, to determine the degree to which integration is associated with FP quality of care when controlling for other facility characteristics. We hypothesized that there are differences in the quality of FP service provision between HIV integrated vs. non-integrated facilities.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study based on secondary datasets from recent SPA conducted in Malawi (2013–2014) and Tanzania (2014–2015). The purpose of the SPA is to assess the availability and quality of basic and essential health services to identify gaps and compare findings across health systems [17, 18]. Four types of data collection instruments are used to understand relevant facility-, provider-, and client-level characteristics: Facility Inventory Questionnaire, Health Provider Interview Questionnaire, Observation Protocols for selected health services (including FP), and Exit Interview Questionnaires for selected clients and caretakers (including FP clients). In sum, these data collection tools provide a comprehensive snapshot of the status of a wide range of basic and essential health services, including those related to FP and HIV.

We used data collected from the Facility Inventory Questionnaire, FP Observation Protocol, and FP Client Exit Interview Questionnaire. The data collection methodology for Malawi and Tanzania were largely identical [17, 18]. A team of data collectors visited each facility to administer questionnaires and observation protocols. For the Facility Inventory Questionnaire, a data collector approached knowledgeable staff members with relevant information to complete each section. For the FP Observation Protocol, data collectors were instructed to observe a maximum of five clients for each provider of the service, with a maximum of 15 observations per service per facility. If several eligible FP clients were present and waiting for an appointment, interviewers sought to select two new clients for every follow-up client. Each client with an observed consultation was approached afterward to complete the FP Client Exit Interview Questionnaire. If the service was not offered on the day that data collectors arrived, there would be a return visit to administer the relevant observation protocol and interviews. However, no return visit was conducted if the service was offered on that day, but no clients came for the service. Consequently, not all facilities in the sample have FP Observation Protocol and FP Client Exit Interview data. Further details on the SPA are reported elsewhere [17,18,19].

Sample

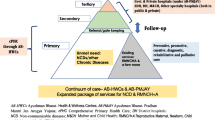

Facilities included in the sample offered any FP services, as recorded in the general service availability section of the facility inventory. In the present study, we define HIV integration as a facility that offers FP services in addition to offering either “HIV/AIDS antiretroviral prescription or antiretroviral treatment follow-up services” or “HIV/AIDS care and support services, including treatment of opportunistic infections and provision of palliative care.” Facilities were considered “non-integrated” if they offered HIV testing and counseling services but neither of the two categories of HIV care and support services. (Note that HIV testing and counseling is a common practice; of facilities offering FP services, 85% in Malawi and 98% in Tanzania also offered HIV testing and counseling services and nearly all facilities included in the analysis in Malawi (119/121) and Tanzania (394/396) provided at least one long acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method.) Importantly, both integrated and non-integrated facilities offered a variety of primary health care services, such as, antenatal care and child health services, in addition to FP. Figure 1 displays a study flowchart of the sample strategy.

Malawi

The Malawi SPA was a census of all formal-sector facilities in the country. In Malawi, 977 of 1060 (92%) facilities were assessed and included in the SPA dataset. Facilities in the sample frame not assessed were for reasons of: refusal (3%), closed down/not yet operational (2%), no respondent available (1%), and inaccessibility (2%). Stratification by type of facility showed that, of the 505 hospitals and health centers offering FP services, only 20 (4%) were non-integrated. Since integration is almost 100% at these types of facilities, they were excluded from the analysis, leaving 388 maternity clinics, dispensaries, clinics, and health posts. Of the 388 facilities, 305 (79%) offer FP services. Of facilities offering FP services, 121 (40%) also offered “HIV/AIDS antiretroviral prescription or antiretroviral treatment follow-up services” or “HIV/AIDS care and support services, including treatment of opportunistic infections and provision of palliative care.” Therefore, the facility-level analytic sample (n = 305) had a smaller proportion of facilities that were HIV integrated (40%) as compared to non-integrated (60%). Of the 305 facilities, 108 facilities had FP client observations (n = 323) and FP client exit interviews (n = 315), and constitute the client-level analytic sample.

Tanzania

The Tanzania SPA was a nationally representative probability-based sample survey of all formal-sector facilities in the country. In Tanzania, 1188 of 1200 facilities (99%) sampled were assessed and included in the SPA dataset. Facilities that were sampled but not assessed (1%) were due to refusal (n = 7), closed down/not yet functional (n = 4), and inaccessibility (n = 1). Stratification by type of facility showed that, of the 183 hospitals offering FP services, only eight (4%) were not HIV integrated. As in Malawi, integration was almost 100% at this level of service provision. Excluding hospitals from the analysis resulted in 937 health centers, clinics, and dispensaries. Of these, 750 (80%) offer FP services. Of facilities offering FP services, 396 (53%) also offered “HIV/AIDS antiretroviral prescription or antiretroviral treatment follow-up services” or “HIV/AIDS care and support services, including treatment of opportunistic infections and provision of palliative care.” Therefore, the facility-level analytic sample (n = 750) was roughly evenly divided by integrated (53%) and non-integrated (47%) status. Of the 750 facilities, 365 facilities had FP client observations (n = 1060) and FP client exit interviews (n = 1059), and comprise the client-level analytic sample.

Measures

Indicators

Indicators from the QIQ were mapped onto SPA measures to create indicators of FP quality of care (Table 1) [20]. The QIQ was developed by the MEASURE Evaluation Project to provide a rapid and low-cost methodology that can be used to routinely measure quality of care in clinic-based family planning programs and related reproductive health services. The QIQ comprises 25 indicators that measure five of six elements from the Bruce/Jain Framework of Quality of Care: choice of methods, information, technical competence, interpersonal relations, and follow-up [11, 20]. The data collection methodology was similar to the SPA in that a Facility Audit Questionnaire, FP Observation Protocol, and Client Exit Interview were developed to assess multiple levels of FP quality of care.

We matched SPA measures to 21 of 25 original QIQ indicators. However, we excluded one of those QIQ indicators (Indicator 20) due to very few clients in the Malawi and Tanzania analytic samples with information on that indicator. Because we treated Indicator 1 as three separate sub-indicators in the analyses, 22 QIQ indicators were used in our analyses. Each indicator was operationalized as a dichotomous variable. An additional file presents the SPA mapping and dichotomization of each QIQ indicator [see Additional file 1, Table S1].

Data analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare each QIQ indicator by HIV integrated vs. non-integrated status. The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to examine whether the distribution of each QIQ indicator significantly differed by integration status. Results are presented as percentages.

Logistic regression analyses were used to determine if integration status was associated with FP quality of care. We estimated unadjusted models of the relationship between integration status and FP quality of care at both the facility- and client-level. In addition, we estimated adjusted models at the facility-level controlling for managing authority (Malawi: 1 = government/public, 2 = private [non-profit], and 3 = private [for profit]; Tanzania: 1 = government/public, 0 = not government/public), facility type (Malawi: 1 = dispensary, 2 = clinic, 3 = health post/maternity; Tanzania: 1 = health center/clinic, 2 = dispensary), zone (for Malawi) or region (for Tanzania), and urban/rural location (1 = rural, 0 = urban). The FP quality of care dependent variables for the facility- and client-level models were sum scores of the respective facility- and client-level QIQ indicators dichotomized at the median. The sum scores included all facility- and client-level indicators except Indicator 9 (Provider gives accurate information on the method accepted [how to use, side effects, complications]) and Indicator 13 (Provider performs clinical procedures according to guidelines), because very few respondents received a relevant service offering, and thus, had no information on the indicator. The facility-level FP quality of care dependent variable included seven indicators, and the sum score ranged 0–7 for both Malawi (median = 4, standard deviation [SD] = 1.64) and Tanzania (median = 4, SD = 1.39). The client-level FP quality of care dependent variable (with indicators from observations and client exit interviews) had 13 indicators and the median score ranged 1–13 for both Malawi (median = 7, SD = 2.03) and Tanzania (median = 7, SD = 2.04).

Analyses were weighted for sample design (Tanzania) and non-response (Malawi) to compensate for any over- or under-representation of facility type in the data. In client-level models, we specified the facility as the primary sampling unit to adjust standard errors for the clustering of clients within facilities. A two-tailed alpha of 0.05 was set for statistical significance. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15.0 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Distribution of facilities by country

Malawi

Of 305 facilities included in the weighted Malawi SPA analytic sample, 39% met the criteria for HIV services integration by offering FP services and at least one of the two HIV care and support services. Table 2 displays facility characteristics in the Malawi sample by integration status. The managing authority of integrated and non-integrated facilities did not significantly differ, with a majority of the sample reporting a private (for profit) managing authority (61%). Most integrated and non-integrated facilities were clinics (80%), though a higher proportion of integrated facilities were a dispensary (18%) than non-integrated facilities (10%). While the location of a facility in an urban or rural setting did not significantly differ by integration status (p = 0.156), a significantly higher proportion (p = 0.006) of integrated facilities were concentrated in northern (17%) and southeastern (24%) zones than non-integrated facilities.

Tanzania

Of 750 facilities included in the weighted Tanzania SPA analytic sample, 38% were HIV integrated, as defined by offering FP services and at least of the two HIV care and support services. Table 3 displays facility characteristics for Tanzanian facilities. Nearly all facilities in the sample reported a government/public managing authority (88%) and rural location (83%). Most integrated (76%) and non-integrated (95%) facilities in the sample were a dispensary. However, a significantly higher proportion of integrated facilities (p < 0.0001) were a health center or clinic (24%) than non-integrated facilities (5%).

Distribution of facilities meeting QIQ indicators, by integration status: bivariate analyses

Malawi

Eleven of 22 QIQ indicators were reported as met by at least half of facilities and clients in each integration category of the Malawi analytic sample (Table 4). Of seven facility-level indicators, only three were met by at least half of facilities in each integrated and non-integrated category. Of fifteen client-level QIQ indicators, eight were reported as met by at least half of clients in each integrated and non-integrated facility category.

Integration status was significantly associated with meeting three QIQ indicators. For facility-level QIQ indicators, integrated facilities were more likely to meet Indicator 18 (Facility has all [approved] methods available; no stockouts; p = 0.039) and Indicator 22 (Facility has received a supervisory visit in past 6 months; p = 0.003), compared with non-integrated facilities. For client-level QIQ indicators, integration status was significantly associated with meeting one of fifteen QIQ indicators. Clients of integrated facilities were more likely than clients of non-integrated facilities to report meeting of Indicator 1a (Look and write on client record; p = 0.005).

Tanzania

Twelve of 22 facility- and client-level QIQ indicators were met by at least half of the Tanzania SPA analytic sample (Table 5). Of seven facility-level indicators, four were met by at least half of integrated and non-integrated facilities in the sample. Of fifteen client-level QIQ indicators, eight were reported as met by clients in at least half of facilities in each integrated and non-integrated category. The sets of QIQ indicators reported by at least half of facilities and clients in Malawi and Tanzania were largely identical, though discrepancies were found (three indicators were reported by at least half of facilities or clients in one country but not another country).

Integration status was significantly associated with meeting four QIQ indicators. Compared with Malawi, integration status was positively associated with Indicator 18 (Facility has all [approved] methods available; no stockouts; p = 0.003) but not Indicator 22 (Facility has received a supervisory visit in past 6 months; p = 0.104). In addition to Indicator 18, integration status was positively associated with Indicator 21 (Facility has mechanisms to make programmatic changes based on client feedback; p = 0.019) and Indicator 23 (Facility has adequate storage of contraceptives and medicines [away from water, heat, direct sunlight] on premises; p = 0.002). At the client-level, integration status was negatively associated with Indicator 25 (Waiting time acceptable; p = 0.005) but not significantly associated with any other client-level QIQ indicator.

Association between integration status and FP quality of care: multivariate analyses

Malawi

In Malawi (Table 6), HIV integrated facilities had two times the odds of being at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care than non-integrated facilities in unadjusted (odds ratio [OR] = 2.18; 95% CI = 1.36, 3.50) and adjusted (OR = 2.24; 95% CI = 1.32, 3.79) facility-level models. Facilities with a private (for profit) managing authority (vs. government/public) had increased odds of being at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care (OR = 5.42; 95% CI = 1.64, 17.91). Health post/maternity facilities had 77% reduced odds of being at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care (OR = 0.23; 95% CI = 0.05, 0.97), compared with dispensaries. There was no significant association of urban/rural location or zone with facility-level FP quality of care. No association was found between integration status and FP quality of care assessed at the client-level (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.48, 2.31).

Tanzania

In Tanzania (Table 7), HIV integrated facilities had twice the odds of being at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care than non-integrated facilities in unadjusted (OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.51, 3.37) and adjusted (OR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.37, 3.22) facility-level models. Dispensaries had lower odds than health center/clinics to be at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care (OR = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.38, 0.84). However, managing authority and urban/rural location were not significantly associated with the likelihood of being at or above the median in facility-level FP quality of care. An association between integration status and FP quality of care assessed at the client-level was not found (OR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.55, 1.51).

Discussion

The present study used publicly available service provision data from Malawi (2013–2014) and Tanzania (2014–2015) to evaluate whether integration of HIV services was associated with FP quality of care. Using the QIQ tool to define and measure FP quality of care, we examined whether integration status was associated with meeting several indicators (in bivariate analyses) and facility- and client-level FP quality of care (in multivariate analyses). To our knowledge, this study is the first study to match SPA measures with the majority (21 of 25) of QIQ indicators to examine service quality. We found that integration status was positively associated with facility-level FP quality of care measures in both countries, as well as a subset of facility- and client-level QIQ indicators in Malawi (n = 3) and Tanzania (n = 4).

Our facility-level bivariate and multivariate analyses found a positive association between integration status and facility-level FP quality of care. The mechanism of this relationship might be best exemplified by the consistent finding in both countries that integrated facilities were more likely than non-integrated facilities to meet criteria for Indicator 18 (Facility has all [approved] methods available; no stockouts). It is possible that HIV integrated facilities in Malawi and Tanzania benefit from strengthened or parallel supply chains implemented to scale-up antiretroviral therapy [21,22,23], and could efficiently receive FP commodities that might also flow through such chains. However, we have no information on facility supply chains in our sample to assess the plausibility of this explanation.

In contrast to facility-level analyses, the relationship between integration status and client-level FP quality of care in Malawi and Tanzania was less clear. Of the 15 client-level QIQ indicators, integration status was significantly associated with just one indicator in Malawi and Tanzania. Moreover, the one indicator that significantly differed by integration status in Tanzania (Waiting time acceptable) was different than Malawi (Look and write on client record) and in the opposite direction. The association between integration status and client-level FP quality of care was null for both countries. These mixed results may suggest that the most robust benefits conferred by integration of HIV services might be primarily infrastructural in nature, and that client-level outcomes that are more dependent on provider skills and capacities might be less influenced. Further research is needed to understand the consequences of integration from the provider and client perspective, and whether this finding is unique to Malawi in sub-Saharan Africa.

Our study findings must be considered along with their limitations. First, our principal data sources are two cross-sectional surveys. Therefore, we lack temporal sequence to establish a causal effect of HIV services integration on FP quality of care. Second, there are no standardized decision rules for meeting of a QIQ indicator. We set indicator criteria in accordance with the original QIQ definition, content knowledge, and data distributions of SPA measures. Consequently, our indicator criteria may be inconsistent with other studies in the literature; other criteria may be equally appropriate but result in different findings. Third, many facilities did not contribute client data through Client Observation or FP Exit Interviews. Due to the incomplete assessment of clients across all facilities, we conducted separate analyses of FP quality of care at the facility- and client-level per country, rather than a single overall analysis utilizing one dependent variable representing FP quality of care. As mentioned, the SPA data collectors would not return to facilities that had no clients visiting for the service on the day of the visit. Therefore, our sample may reflect busier facilities that have less time available for clients, and consequently perform worse on client-level indicators than facilities that are less busy and have more time to provide better quality service to FP clients. Fourth, our data-driven dichotomization of FP quality of care may limit comparison of our findings to other studies. However, the dichotomization scheme provides insight as to how integrated facilities perform relative to non-integrated facilities in the countries, according to country-specific baseline levels of FP quality of care. Finally, our analysis focused on primary and secondary health care facilities, as virtually all tertiary facilities were found to meet the criteria for integration. Results should not be interpreted for tertiary level facilities in these countries.

Our study had many strengths. We used the most recent, nationally representative data available, thereby providing valuable insight that may inform current policymaking regarding integrated FP programs. The present study is one of the few that leveraged SPA data, which is relatively underutilized given the critical need for research on topics of health system strengthening in developing countries. We used the QIQ to conduct a theory-based evaluation of FP quality of care that does not rely on single subjective measures of quality, as is common in the literature. As a result, our assessment of FP quality of care in integrated and non-integrated settings amounts to a significant contribution to the evidence base.

Conclusion

Research on the relationship between integration of HIV services and FP quality of care is necessary to ensure that service integration results in high quality care that improves service delivery and benefits clients’ health. Using service provision data from Malawi and Tanzania, we found that integration is beneficially associated with facility-level FP quality of care. However, results were mixed at the client-level.

Our findings did not confirm concerns regarding the potential adverse consequences of HIV and FP services integration. Though research on stakeholder perspectives regarding integration implementation indicate concern that integration may overburden facilities and negatively affect quality [4], we found only one negative association indicating that integration of HIV services may negatively affect provider practice (i.e. reduced likelihood of acceptable waiting time in Tanzania). In general, our findings suggest that FP quality of care may be equivalent or superior in integrated facilities compared with non-integrated facilities in Malawi and Tanzania. Further research is needed to understand how HIV services integration may impact FP quality of care in diverse settings, and how the platform in which FP is integrated may differentially influence FP quality of care.

A French translation of this article has been included as Additional file 2.

A Portuguese translation of the abstract has been included as Additional file 3.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FP:

-

Family planning

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- QIQ:

-

Quick Investigation of Quality

- SPA:

-

Service Provision Assessment

References

Johnson K, Varallyay I, Ametepi P. Integration of HIV and family planning services in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the literature, current recommendations, and evidence from the service provision assessment health faculty surveys [Internet]. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2012 Sep. Report No.: 30. [Accessed 7 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-AS30-Analytical-Studies.cfm.

Barden-O’Fallon J, Adamou B, Mejia C, Agala CB. A review of family planning outcomes in integrated health programs and research recommendations — MEASURE Evaluation [internet]: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2017. Accessed 10 Jul 2017] Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/wp-17-176

Foreit KGF, Hardee K, Agarwal K. When does it make sense to consider integrating STI and HIV services with family planning services? Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2002:105–7.

MEASURE Evaluation. Findings from a Multi-Country Assessment of Integrated Health Programs [Internet]. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2014 Aug. [accessed 2017 Sep 10] Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-14-115.

Ringheim K, Yeakey M, Gribble J, Sines E, Stepahin S. Supporting the integration of family planning and HIV services. [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: Population Reference Bureau; 2009 Sep. [Accessed 7 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/557931.

Duerr A, Hurst S, Kourtis AP, Rutenberg N, Jamieson DJ. Integrating family planning and prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2005;366:261–3.

Church K, Mayhew SH. Integration of STI and HIV prevention, care, and treatment into family planning services: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plan. 2009;40:171–86.

Stover J, Fuchs N, Halperin D, Gibbons A, Gillespie D. Costs and benefits of adding family planning to services to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT). How family planning can increase the benefits of PMTCT by saving lives and reducing the number of orphans. [Internet]. 2003 Jul. [Accessed 7 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/276464.

Adamchak S, Janowitz B, Liku J, Munyambanza E, Grey T, Keyes E. Study of family planning and HIV integrated services in five countries [Internet]. Research Triangle Park, NC, USA: Family Health International; 2010. [Accessed 8 Sep 2017] Available from: http://addiscontinental.edu.et/files/FPHIVInt5countryreport.pdf.

Sherr L. Literature review on program strategies and models of continuity of HIV/maternal newborn and child health care for HIV-positive mothers and their HIV-positive/−exposed children. [Internet]. Arington, VA, USA: AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources, Task Order 1 (AIDSTAR-One); 2012 Feb. [Accessed 8 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/561593.

Bruce J. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Stud Fam Plan. 1990;21:61.

Spaulding AB, Brickley DB, Kennedy C, Almers L, Packel L, Mirjahangir J, et al. Linking family planning with HIV/AIDS interventions: a systematic review of the evidence. AIDS. 2009;23:S79–88.

Coyne KM, Hawkins F, Desmond N. Sexual and reproductive health in HIV-positive women: a dedicated clinic improves service. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:420–1.

PATH. Preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission [internet]. PATH; 2006 [Accessed 7 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.path.org/publications/files/ER_directions_summer06.pdf.

Mullick S, Askew I, Maluka T, Khoza D, Menziwa M. Integrating counselling and testing into family planning services: what happens to the existing quality of family planning when HIV services are integrated in South Africa? Addis Ababa: Ethiopia; 2006. p. 9–10

Reynolds HW, Liku J, Beaston-Blaakman A, Kimani J, Burke H. Integrating family planning services into voluntary counseling and testing centers in Kenya. Operations research results. [Internet]. Research Triangle Park, NC, USA: Family Health International; 2006 Jul. [Accessed 7 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.popline.org/node/179189.

Ministry of Health- MoH/Malawi, ICF International. Malawi Service Provision Assessment 2013–14 [Internet]. Lilongwe, Malawi, and Rockville, MD, USA: MoH/Malawi and ICF International; 2014. [Accessed 8 Sep 2017] Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-spa20-spa-final-reports.cfm.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare/Tanzania, Ministry of Health/Zanzibar, National Bureau of Statistics/Tanzania, Office of Chief Government Statistician/Tanzania, ICF International. Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey 2014–2015 [Internet]. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Rockville, MD, USA: MoHSW, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF International; 2016 Feb. [Accessed 8 Sep 2017] Available from: http://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-spa22-spa-final-reports.cfm

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The DHS program - service provision assessments (SPA) [internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 10]. [Accessed 10 Jul 2017] Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm.

MEASURE Evaluation. Quick investigation of quality: a User’s guide for monitoring quality of Care in Family Planning (2nd ed.) [internet]. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: MEASURE Evaluation: University of North Carolina; 2016. [Accessed 10 Jul 2017] Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/ms-15-104

Windisch R, Waiswa P, Neuhann F, Scheibe F, de Savigny D. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: using supply chain management to appraise health systems strengthening. Glob Health. 2011;7:25.

El-Sadr WM, Holmes CB, Mugyenyi P, Thirumurthy H, Ellerbrock T, Ferris R, et al. Scale-up of HIV Treatment Through PEPFAR: A Historic Public Health Achievement. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2012;60:S96–104.

Schouten EJ, Jahn A, Ben-Smith A, Makombe SD, Harries AD, Aboagye-Nyame F, et al. Antiretroviral drug supply challenges in the era of scaling up ART in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:S4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The journal supplement is made possible by the generous support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in partnership with United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). General support is provided by the Carolina Population Center and its NIH Center grant (P2C HD050924).

The views expressed in this publication are solely the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the USAID, UNFPA or UNAIDS, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the U.S. Government, UNFPA or UNAIDS.

Availability of data and materials

De-identified Service Provision Assessment data are available for public use with registration at http://dhsprogram.com.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Reproductive Health, Volume 16 Supplement 1, 2019: Effective Integration of Sexual Reproductive Health and HIV Prevention, Treatment, and Care Services across sub-Saharan Africa: Where is the evidence for program implementation? The full contents of the supplement,published as a joint collaboration between Reproductive Health and BMC Public Health, are available online at https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-16-supplement-1 and https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JBO and CM designed and conceptualized the study; MC ensured the quality of the data; MC, JBO, CM analyzed the data; and all critically interpreted the data. CM and MC drafted the article; and JBO critically revised it. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Office of Human Research and Ethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill determined that this analysis of secondary data did not constitute human subjects research as defined under federal regulations, and therefore, did not require institutional review board approval. Consent and ethics approval were obtained by ICF Macro (the DHS Program) prior to data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, there is no personally identifiable individual-level data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Description of Matched QIQ and SPA Measures in Present Study. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Translation of this articles into French. (PDF 361 kb)

Additional file 3:

Translation of the abstract of this article into Portuguese. (PDF 115 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Close, M., Barden-O’Fallon, J. & Mejia, C. Quality of family planning services in HIV integrated and non-integrated health facilities in Malawi and Tanzania. Reprod Health 16 (Suppl 1), 58 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0712-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0712-y