Abstract

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and HIV-2) use cellular receptors in distinct ways. Besides a more promiscuous usage of coreceptors by HIV-2 and a more frequent detection of CD4-independent HIV-2 isolates, we have previously identified two HIV-2 isolates (HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97) that do not use the two major HIV coreceptors: CCR5 and CXCR4. All these features suggest that in HIV-2 the Env glycoprotein subunits may have a different structural organization enabling distinct - although probably less efficient - interactions with cellular receptors.

Results

By infectivity assays using GHOST cell line expressing CD4 and CCR8 and blocking experiments using CCR8-specific ligand, I-309, we show that efficient replication of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 requires the presence of CCR8 at plasma cell membrane. Additionally, we disclosed the determinants of chemokine receptor usage at the molecular level, and deciphered the amino acids involved in the usage of CCR8 (R8 phenotype) and in the switch from CCR8 to CCR5 or to CCR5/CXCR4 usage (R5 or R5X4 phenotype). The data obtained from site-directed mutagenesis clearly indicates that the main genetic determinants of coreceptor tropism are located within the V1/V2 region of Env surface glycoprotein of these two viruses.

Conclusions

We conclude that a viral population able to use CCR8 and unable to infect CCR5 or CXCR4-positive cells, may exist in some HIV-2 infected individuals during an undefined time period, in the course of the asymptomatic stage of infection. This suggests that in vivo alternate molecules might contribute to HIV infection of natural target cells, at least under certain circumstances. Furthermore we provide direct and unequivocal evidence that the usage of CCR8 and the switch from R8 to R5 or R5X4 phenotype is determined by amino acids located in the base and tip of V1 and V2 loops of HIV-2 Env surface glycoprotein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) envelope (Env) glycoproteins are responsible for initial molecular interactions between HIV and cellular receptors present in plasma membrane. The sequential and specific interaction of Env surface (SU) glycoprotein with CD4 and a member of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), enables the disclosure of a hydrophobic region (called fusion peptide) in Env transmembrane glycoprotein that leads to the fusion of viral envelope with cell membrane [1],[2].

The two major GPCRs (known as coreceptors) involved in this complex entry mechanism are CCR5 and CXCR4 [1]-[6]. However, several other GPCRs have been implicated as coreceptors [7]-[21], revealing that HIV-1 and HIV-2 isolates can exploit alternate molecules in vitro as co-factors for viral entry, raising the possibility that they might contribute to HIV infection of natural target cells in vivo. These alternate coreceptors include: CCR2b, CCR3, CCR4, CCR6, CCR8, CCR9, CCR10, CXCR2, CXCR5, CXCR6, CX3CR1, XCR1, FPRL1, GPR1, GPR15, APJ, ChemR23, CXCR7/RDC1, D6, BLTR and US28.

The importance of CCR5 and CXCR4 as HIV coreceptors emanates from (i) the apparent selection of CCR5-using (R5) variants during or soon after HIV-1 mucosal transmission [22]; (ii) the almost exclusive presence of R5 HIV-1 variants during chronic infection; and (iii) the emergence and predominance of CXCR4-using (X4) variants in some patients with advanced HIV-1 disease [23].

We and others have previously demonstrated that in vitro, HIV-1 and HIV-2 use cellular receptors in distinct ways, including (i) more promiscuous usage of coreceptors by HIV-2 [24]-[27]; (ii) more frequent detection of CD4-independent HIV-2 isolates [28]-[31]; and (iii) identification of CCR5/CXCR4-independent HIV-2 isolates [7],[32]. All these features suggest that in HIV-2 the Env glycoprotein subunits may have a different structural organization enabling distinct (although probably less efficient) interactions with cellular receptors.

In HIV-1, the molecular determinants governing coreceptor usage by a certain isolate are located mainly in the third variable region (V3) of SU glycoprotein [33]-[37]. In HIV-1 subtype B, the presence of basic (positively charged) amino acids at positions 11, 25 and/or 24 (referred to V3 region), an overall charge of V3 region above +6 and the loss of an N-linked glycosylation site within the V3 region are consistently associated with CXCR4 usage [1],[2],[38]-[40]. Besides V3 region, also the variable regions 1 and 2 (V1/V2) have been described as cooperating in coreceptor’s choice [1]-[6],[41]-[43].

In HIV-2, structural and functional studies of envelope glycoproteins regions are much more scarce and in some aspects contradictory. Some studies had claimed an association between V3 loop sequence and CCR5 or CXCR4 usage [7]-[21],[44]-[47], while others had found no genetic signature underlying coreceptor usage [22],[27],[48],[49]. Particularly, the C-terminal region of the V3 loop, a global net charge above +6 and the presence of mutations in amino acids 18 and 19 (numbers refer to V3 sequence), appear to dictate the ability to use CXCR4 alone or in addition to CCR5 [23],[45],[47].

During a screening of HIV-2 primary isolates regarding coreceptor usage, we identified two strains obtained from asymptomatic individuals (HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97) that enter target cells independently of CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors [7],[24]-[27]. Here the virus-receptors interactions and the SU Env glycoprotein characteristics of these two viruses were further studied in order to (i) decipher which are the molecules used by these isolates to enter target cells; and (ii) which are the molecular determinants underlying the CCR5/CXCR4-independent entry. We provide direct evidence that CCR8 is the cellular receptor engaged as coreceptor by these specific strains. Furthermore, we also demonstrate that the molecular determinants of this phenotype are located in the V1/V2 region of SU Env glycoprotein, providing valuable new insights into the basis of HIV-2 envelope interactions with cellular receptors.

Results

The interactions between cellular coreceptors and Env glycoproteins from two CCR5/CXCR4-independent HIV-2 strains were investigated. In the first part of this study we identified the CCR8 molecule as the coreceptor used by both strains for viral entry. In the second part, we addressed the determinants of chemokine receptor usage at the molecular level, and deciphered the amino acids involved in the usage of CCR8 and in the switch from CCR8 to CCR5 or to CCR5/CXCR4 usage.

HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 uses CCR8 to infect GHOST cell lines and PBMC

Our previous results showed that both HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 are unable to infect GHOST-CD4 cell lines expressing several coreceptors including CCR5 and CXCR4 [7],[28]-[31]. The CCR5/CXCR4-independent phenotype was demonstrated either in ccr5 Δ32/Δ32 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) infection, and by testing the in vitro resistance to CCR5 and CXCR4 targeted inhibitors [7],[32].

Since both viruses required the presence of CD4 at cell membrane [7],[33]-[37] together with an unknown coreceptor present in IL-2-activated PBMC, our first goal was to identify this elusive molecule. We initially characterize chemokine receptors usage, by infectivity assays using GHOST-CD4 and U87-CD4 cell lines expressing several chemokine receptors (CCR1, CCR2b, CCR3, CCR5, CXCR4, GPR15 and CXCR6). To further extend these results, we analyzed HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 utilization of a panel of other potential coreceptors. For this, GHOST-CD4/Hi5, GHOST-CD4/CCR8 and GHOST-CD4/CX3CR1 cell lines were infected with 100 TCID50 of each virus. As controls, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cell lines and PBMC were included as well as HIV-2ROD (able to use both CXCR4 and CCR5 coreceptors; biotype R5X4) and HIV-1Ba-L (able to use CCR5 coreceptor; biotype R5) viral strains. The results (Figure 1) show that only PBMCs and GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells are able to support efficiently the replication of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 (p < 0.001), indicating that these strains require the presence of CCR8 to enter host cells. Viral replication was assessed by measuring RT activity in culture supernatants of infected cells; however, since GHOST cell line carries HIV-2 long terminal repeat (LTR)-driven green fluorescent protein (GFP), we also assessed coreceptor usage by analyzing GFP expression in GHOST-CD4/CCR8, GHOST-CD4/Hi5, GHOST-CD4/CX3CR1, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 infected cells by fluorescent microscopy (Table 1). This analysis was done in triplicate at days 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 post-infection and confirms the exclusive usage of CCR8 as coreceptor by HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97.

HIV-2 MIC97 and HIV-2 MJC97 use CCR8 as coreceptor to infect GHOST-CD4 cells and PBMC. PBMC and GHOST-CD4 cell lines expressing different coreceptors were exposed to 100 TCID50 of each virus; viral replication was quantified by RT activity in culture supernatants during a 12-day period after infection and the highest value of RT activity observed during this time period was used. Results are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. A star (*) indicates statistical significant difference (p < 0.001) between the means of peak RT activity measured in culture supernatants of GHOST-CD4/CCR8 inoculated with HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97, compared with GHOST-CD4/CCR5, GHOST-CD4/CXCR4, GHOST-CD4/CX3CR1, and GHOST-CD4/Hi5 inoculated with the same viruses.

The robust usage of CCR8 revealed by GHOST cells assay, prompted us to further confirm the role of this alternate coreceptor in HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 entry. In order to assure the specificity of CCR8 usage, we incubated 1 × 106 GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells and PHA-activated CD8-depleted PBMCs with blocking concentrations (100 ng/ml) [50],[51] of the CCR8 natural ligand, I-309, prior to the addition of 100 TCID50 of each viral strain. As shown in Figure 2, I-309 inhibited the infection of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC-97 replication. The replication of both viruses was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) for a concentration of 100 ng/ml in both GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cell line and CD8-depleted PBMCs, further confirming that CCR8 coreceptor was essential for viral entry including in primary cells. As controls, we also tested the ability of I-309 to inhibit the replication of HIV-2ROD and HIV-1Ba-L. In both cases the viral replication was not affected by the addition of I-309 (Figure 2).

Specific inhibition of HIV-2 MIC97 and HIV-2 MJC97 by I-309. GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cell line and CD8-depleted PBMCs were inoculated with 100 TCID50 of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 either in the presence or absence of CCR8 ligand, I-309. HIV-2ROD and HIV-1Ba-L were also included as controls. The data are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Generation of CCR5-using and CCR5/CXCR4-using variants of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97

The identification of CCR8 as the coreceptor that, together with CD4, enables cell entry by these two strains raised several important questions. One is related to the fact that a population of CCR5-independent variants could maintain a persistent HIV infection in vivo. If so, what will be the evolution of this population within the infected patient regarding coreceptor usage? In addition, if this evolution eventually occurs what will be the differences in Env glycoproteins sequences between those isolates? To answer these questions we made efforts to obtain sequential blood samples of the same patients from which we isolated HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97. Unfortunately both patients had left medical outpatient clinic follow-up and therefore it was unfeasible to obtain further samples to help answer these questions.

In order to study the evolution of coreceptor usage (i.e. from CCR8 to CCR5 and/or CXCR4) and thus the HIV-2 envelope glycoproteins determinants that are important in CCR5/CXCR4-independent replication, alternatively we performed an in vitro replication adaptation of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 to CCR5- or CXCR4-expressing cell lines. The starting viruses for this study was obtained by transfection of 293 T cells with the pROD/MIC-SB and pROD/MJC-SB plasmids [52]. These plasmids contain an infectious HIV-2ROD provirus into which the env gene derived from both HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 isolates, was cloned [52]. The cells used in this experiment were the GHOST-CD4 cell lines individually expressing CCR8, CCR5 or CXCR4. An initial stock of each virus (ROD/MIC-SB and ROD/MJC-SB) was prepared by passing the virus-containing supernatants from transfected 293 T cells in GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells. Each virus was then used to infect a 90:10 mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4. At day 12 after infection, culture supernatants were used to infect either a pure population of GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells, and a 80:20 mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4. Virus-containing supernatant from these latter cultures was again used to infect pure GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells and a 70:30 mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4. This procedure was repeated using cell mixtures with increasing proportions of GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells, until a ratio 10:90 of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells. In each step of this adaptation study, the viral supernatants of each inoculated culture (either mixtures or pure populations) were monitored by reverse transcriptase activity in order to detect viral replication. The results reveal that viral progeny was detected in all culture supernatants; however, we could not detect in any occasion the productive infection of pure GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells (data not shown). Thus, this serial passage of R8 viruses in a cell population with increasing proportions of CCR5-positive or CXCR4-positive cells did not allowed the in vitro selection of mutants with the ability to use either of these coreceptors.

Construction of V1/V2 mutants by site-directed mutagenesis

Due to inability to generate coreceptor switch mutants in vitro, we decided to create and test a panel of isogenic viruses derived from HIV-2MJC97 differing only in specific amino acids residues, enabling the analysis of the impact of different Env glycoproteins mutations in coreceptor usage by HIV-2MJC97.

Previously, we described that env-chimeric viruses derived from HIV-2ROD with the SU glycoprotein from either HIV-2MIC97 or HIV-2MJC97 were unable to infect CD4/CCR5 or CD4/CXCR4 expressing cells, indicating that the C1-C4 region of SU glycoprotein was the only determinant of CCR5/CXCR4-independent phenotype [52]. We also found by comparative env gene sequence analysis, that HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 show remarkable differences in primary amino acid sequence, particularly in the V1/V2 region of each SU glycoproteins [49]. Not surprisingly, but worth noting, despite the differences observed in V1/V2 region we could not identify any discrete sequence signatures that could be hypothetically assigned to the phenotype presented by these two strains [49]. To gain deeper insights into the potential role of V1/V2 domain of Env glycoprotein with regard to coreceptor usage we constructed a variety of different recombinant viruses, all derived from an env-chimeric virus (ROD/MJC-SA) described earlier [52] that contains the C1-C4 region of HIV-2MJC97env gene inserted into the HIV-2ROD backbone by homologous substitution using an infectious molecular clone derived from pROD10 [28]. Multi-site directed mutagenesis of the V1/V2 domain of ROD/MJC-SA env was performed targeting the base and the tip of V1 and V2 loops. The details of mutations introduced in each recombinant virus are presented in Table 2 and Figure 3. The first set of mutated viruses (MJC97mt1 to MJC97mt7) was obtained by sequential mutagenesis starting from the V1/V2 env region of wild type ROD/MJC-SA (MJC97wt). The second set of mutants (MJC97mt5′ to MJC97mt7′) was derived from the V1/V2 of MJC97mt4. Following each mutagenesis step, the C1-C4 coding region was sequenced to confirm that only the desired changes were introduced.

Amino acid residues changed in V1/V2 region of env glycoprotein by site-directed mutagenesis. Amino acids are denoted by single-letter code. (A) For a better localization of mutated amino acids, the sequence alignment between HIV-2ROD (GenBank accession number: M15390) and HIV-2MJC97 (GenBank accession number: EU021092) was included. The red boxes indicate the conserved regions between HIV-2ROD and HIV-2MJC97 amino acids sequences. (B) The first set of mutants (MJC97mt1 to MJC97mt7) was obtained by sequential mutagenesis starting in the non-mutated recombinant virus, MJC97wt. The second set of mutants (MJC97mt5′ to MJC97mt7′) was derived from the V1/V2 of MJC97mt4. For each sequential mutant, underlined red letters represents the newly changed amino acids residues, while the non-underlined red letters denote mutations that were previously added. Amino acids residues (in panel A and B) were numbered according to HIV-2ROD (GenBank accession number: M15390) or HIV-2MJC97 sequence (GenBank accession number: EU021092).

The rationale for the selected mutagenesis was based in the env sequence analysis and in the discrepancies observed between the V1/V2 coding sequences of HIV-2MJC97 (GenBank Accession No. EU021092) and those from R5-tropic HIV-2ALI (GenBank Accession No. AF082339) [28],[30] and R5/X4 HIV-2ROD strains (GenBank Accession No. M15390) [53]. Using this approach we were able to construct a total of 10 different recombinant coding sequences (Figure 3) containing combined mutations in the V1/V2 region, all included in the genetic backbone of the R5/X4-tropic HIV-2ROD strain [52]. The mutated recombinant coding sequences were used to reconstitute replication-competent viruses by transfection in 293 T cells, and further expanded in IL2-stimulated PBMC. Although all chimeric viruses were able to replicate in PBMC, the replication efficiency was importantly reduced in some mutated viruses, namely MJC97mt6 and MJC97mt6′ (Figure 4), indicating that the modification of certain V1/V2 motifs indeed strongly affect the replication fitness of recombinant viruses.

Effect of sequential mutations in V1/V2 region of HIV-2 MJC97 env glycoprotein on coreceptor usage. Stocks of each mutated virus (the details of these mutants are described in Figure 3) were used to infect PHA-activated PBMCs and GHOST-CD4 cell lines individually expressing CCR8, CCR5, and CXCR4 coreceptors. (A) Viral replication was followed-up for 12 days by assessing RT activity in culture supernatants of infected cells. The highest value of RT activity observed during this time period was used. A star (*) indicates statistical significant difference (p < 0.001) between the means of peak RT activity measured in culture supernatants of GHOST-CD4/CCR8, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 inoculated with MJC97mt7 compared to the same cells inoculated with MJC97wt. Conversely, a double star (**) denotes statistical significant difference (p < 0.001) between the means of peak RT activity measured in culture supernatants of GHOST-CD4/CCR8, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 inoculated with MJC97mt7′ compared to the same cells inoculated with MJC97wt. The strains HIV-2ALI (R5), HIV-2ROD (R5X4) and HIV-2MJC97 (R8) were used as controls. Replication kinetics of MJC97wt was compared to mutant viruses that switch from CCR8 usage to CCR5/CXCR4 (MJC97mt7) or to CCR5 ( MJC97mt7′); HIV-2ROD and HIV-2ALI strains were also included as controls. The replication kinetics, assessed by RT activity in culture supernatants, was followed up during 21 days and was performed in PHA-activated PBMCs (B), GHOST-CD4/CCR8 (C), GHOST-CD4/CCR5 (D) and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 (E). In all experiments, results are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Coreceptor usage by mutated recombinant viruses

To gain greater definition into the nature of the relationship between V1/V2 and cellular receptors engagement in HIV-2, an initial stock of mutated viruses (MJC97mt2, MJC97mt4, MJC97mt6, MJC97mt7, MJC97mt6′ and MJC97mt7′) was prepared by passing each viral-containing supernatants from transfected 293 T cells in IL2-stimulated PBMC. Each replication-competent virus stocks were used to analyze coreceptor usage patterns on GHOST-CD4 cells expressing different coreceptors (CCR5, CXCR4 and CCR8). The objective was to assess the potential implications of the sequential mutations introduced in the V1/V2 regions on coreceptor choice. Viral stocks from MJC97mt2, MJC97mt4, MJC97mt6, MJC97mt7, MJC97mt6′ and MJC97mt7′ were inoculated in GHOST cells and PBMC, and viral replication was followed-up for 12 days by measuring RT activity in culture supernatants of infected cells. The mean of peak RT activity of three independent experiments performed in duplicate was calculated. As controls, GHOST cells and PBMC were also inoculated with HIV-2MIC97, HIV-2MJC97, R5 strain HIV-2ALI and the R5/X4 strain HIV-2ROD, obtained after transfection of 293 T cells with pROD10, an infectious molecular clone of HIV-2ROD [54]. As shown in Figure 4 (panel A), MJC97mt7 clearly show a switch in coreceptor usage from CCR8 to CCR5/CXCR4 (p < 0.001), while MJC97mt7′ changed from CCR8 to CCR5 usage (p < 0.001). Noteworthy, all the other mutants maintained their ability to use CCR8, similarly to the wild-type (MJC97wt), although some of them noticeable with less efficiency (e.g. MJC97mt6 and MJC97mt6′).

To further assess the viral replication efficiency of MJC97mt7 and MJC97mt7′ we infected PBMCs and GHOST-CD4 cell lines individually expressing CCR8, CCR5 and CXCR4. Besides the mutants that effectively changed from R8 to R5X4 (MJC97mt7) and from R8 to R5 ( MJC97mt7′), we also included MJC97wt, HIV-2ROD and HIV-2ALI (as controls). The results summarized in Figure 4 (panels B to E), indicates that the coreceptor switch from CCR8 (MJC97wt) to CCR5 ( MJC97mt7′) or to CCR5/CXCR4 (MJC97mt7) was not followed by an increase in replication kinetics, regardless the mutated virus considered, suggesting that different regions besides V1/V2 influence replication kinetics. This is in accordance with our previous observation pointing to the transmembrane domain of Env glycoproteins as major determinant for the lower replication rate observed in both HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 [52]. Additionally, we also notice that the levels of RT activity in GHOST cell lines and PBMCs were not significantly different. Considering the described higher cellular densities of CD4 and coreceptor molecules in GHOST cells [55],[56] and since the concentration of receptors on cell surface has a direct impact in viral entry events [57] it was surprising this similarity in viral replication. However, we do not access viral entry efficiency but instead we used de novo viral production as marker of efficient infection. The production of viral particles de novo is the result of many other factors besides viral entry through the interaction with cell receptors. Accordingly, replication efficiency is the result of the overall contribution of several events besides viral entry step. A possible explanation for the similar levels of RT activity in GHOST cell lines and PBMCs is that the minor cell receptors expression in PBMC is compensated by more efficient intracellular events during the entire replication cycle compared to GHOST cell lines.

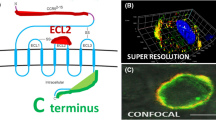

Based on previous reports addressing antibody binding and cysteine loops mapping of HIV-2 SU glycoprotein [58],[59], we located the mutations of MJC97mt7 and MJC97mt7′ either on the tip or base of V1 and V2 loops (Figure 5).

Location of amino acids residues involved in coreceptor usage. Schematic representation of the envelope SU glycoprotein of HIV-2MJC97 putative secondary structure spanning from C1 to V3 regions. The amino acid sequence of HIV-2MJC97 (MJC97wt; R8) are represented in black; the mutated amino acids present in MJC97mt7 (R5X4; panel A) and MJC97mt7′ (R5; panel B) are represented in red. Amino acids are denoted by single-letter code. The underlined amino acids represent potential glycosylation sites linked to asparagine (N) as defined using the LANL N-glycosite program (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html). Amino acids residues were numbered according to HIV-2MJC97 sequence (GenBank accession number: EU021092). This schematic representation was based on previous data regarding epitope and cysteine loops mapping [58],[59].

Interestingly, although MJC97mt6 and MJC97mt6′ still maintained the ability to infect GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells, they also show the ability to infect GHOST-CD4/CCR5 ( MJC97mt6′) or GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells (MJC97mt6). This transitional state from R8 to R5X4 or R8 to R5 phenotype was acquired after mutational change of the tip of V1 region (Figures 3 and 5). Noteworthy, both MJC97mt6 and MJC97mt6′ show a decreased replication in GHOST-CD4/CCR8 compared to MJC97wt (p < 0.001 in both cases).

These results suggest that amino acid residues in the crown of V1 loop are a critical determinant for the switch from CCR8 to CCR5 or CCR5/CXCR4 usage and thus for Env-coreceptor interactions. The mutated amino acids encompass the motif ISTTDYSL (amino acids residues 113 to 120 according to HIV-2MJC97 sequence, GenBank Accession No. EU021092; Figures 3 and 5) present in MJC97wt (R8 phenotype) that was changed to PGSTLKPL (the mutated amino acids correspond to the italicized letters) present in MJC97mt6′ (R8R5 phenotype) and MJC97mt7′ (R5 phenotype) or to IPTDQEQE present in MJC97mt6 (R8R5X4) and MJC97mt7 (R5X4 phenotype). To further address the suggested critical role of the V1 crown as molecular determinant for viral coreceptor-tropism switch, we constructed four additional mutants (Figure 6). In two of these mutants only the motif ISTTDYSL was changed: MJC97mtV1 carrying the sequon IPTDQEQE; and MJC97mtV1′ carrying the sequon PGSTLKPL (the mutated amino acids correspond to the italicized letters). In the other two mutants we combined the referred mutations in the tip of V1 region with additional mutations located at the base of the V2 region, where the sequon PTNET (MJC97wt) was replaced in MJC97mtV1 by TNNES (originating MJC97mtV1V2); and in MJC97mtV1′ was replaced by PFNTT (originating MJC97mtV1V2′). As shown in Figure 7 mutating the tip of V1 region alone or combined with mutations at the base of V2 region, did not confer the ability to efficiently use CCR5 (MJC97mtV1′ or MJC97mtV1V2′) or CCR5 and CXCR4 (MJC97mtV1 or MJC97mtV1V2). Together these results clearly indicate that although coreceptor switch is dependent on mutations in ISTTDYSL sequon it requires additional changes in other regions of V1/V2. Conversely, they also emphasize that changes in a single amino acid - even if it is relevant - can have phenotypic consequences that are context dependent, relying on the simultaneous presence of additional mutation that may be required to stabilize the interaction with a given coreceptor. The need for cooperating mutations and the viral fitness disadvantage of intermediate mutants - as shown in MJC97mt6 and MJC97mt6′ - when compared with the initial viruses (p < 0.001), could help explain the unsuccessful in vitro adaptation experiments.

Amino acid sequences of mutants targeting the tip of V1 region and the base of V2 loop. (A) For a better localization of mutated amino acids, the sequence alignment between HIV-2ROD (GenBank accession number: M15390) and HIV-2MJC97 (GenBank accession number: EU021092) was included. The red boxes indicate the conserved regions between HIV-2ROD and HIV-2MJC97 amino acids sequences. (B) The tip of V1 of MJC97wt has the sequon ISTTDYSL (amino acids residues 113–120) that was changed to IPTDQEQE (MJC97mtV1) or PGSTLKPL (MJC97mtV1′). The MJC97mtV1V2 was obtained by replacing the sequon PTNET (amino acids residues 172–176) in the base of V2 loop of MJC97mtV1 by TNNES; MJC97V1V2′ was originated by changing the referred sequon of MJC97mtV1′ by PFNTT. Amino acids residues (in panel A and B) were numbered according to HIV-2ROD (GenBank accession number: M15390) or HIV-2MJC97 sequence (GenBank accession number: EU021092).

Coreceptor usage of mutants targeting the tip of V1 region and the base of V2 loop. Recombinant viruses with mutations targeting the tip of V1 region (MJC97mtV1 and MJC97mtV1′) or with additional mutations in the base of V2 loop (MJC97mtV1V2 and MJC97mtV1V2′). The details of these two sets of mutants are described in Figure 6. Viral replication was followed-up for 12 days by assessing RT activity in culture supernatants of infected cells. The highest value of RT activity observed during this time period was used. Results are expressed as the mean of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. A star (*) indicates statistical significant difference (p < 0.001) between the means of peak RT activity measured in culture supernatants of GHOST-CD4/CCR8, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 inoculated with MJC97mt6 and MJC97mtV1 or MJC97mt7 and MJC97mtV1V2. A double star (**) indicates statistical significant difference (p < 0.001) between the means of peak RT activity measured in culture supernatants of GHOST-CD4/CCR8 and GHOST-CD4/CCR5 inoculated with MJC97mt6′ and MJC97mtV1′ or MJC97mt7′ and MJC97mtV1V2′.

In conclusion, our data clearly show that the main genetic determinants of coreceptor tropism are located within the V1/V2 region of SU glycoprotein and include the crown of V1 loop and discrete amino acids present in: (i) the tip of V2; (ii) the base of V1; and (iii) the base of V2. This emphasizes the plasticity with which SU glycoproteins can interact with coreceptors and the variety of molecular determinants that can influence this interaction.

Discussion

HIV entry into susceptible cells requires the presence of CD4 and a chemokine receptor (coreceptor), usually CCR5 or CXCR4. However, other alternate coreceptors have been described and may play an effective role in HIV-1 and HIV-2 entry.

We previously showed that two HIV-2 primary isolates could infect susceptible cells by a CCR5/CXCR4-independent pathway [7]. Herein, we extend the study of this model aiming the disclosure of: (i) the alternate coreceptor used by these HIV-2 isolates (HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97) and (ii) the amino acids residues responsible for the CCR5/CXCR4-independent entry.

In the first part of the study we identified CCR8 as the coreceptor used by HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 to infect host cells. The restrict use of CCR8 by HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 indicates that a viral population present in HIV-2 infected individuals during asymptomatic stage could use other coreceptors besides or instead CCR5 and CXCR4. Although these two chemokine receptors are considered as the major coreceptors for HIV entry into host cells, the possibility that alternative molecules could have physiological relevance in vivo as cofactors for HIV infection remains open. In fact, a growing body of evidence indicates that both HIV-1 and HIV-2 isolates can use distinct coreceptors in vitro together with or alternatively to CCR5 and CXCR4 [7]-[11],[14],[16],[17],[19],[20],[32],[60],[61]. In particular, CCR8 usage was referred in earlier reports either in indicator cell lines (e.g. GHOST, U87 or NP2 cells) or in primary lymphocytes [9],[14],[17],[19],[29],[51],[62]-[66]. More recently, we studied the relevance of CCR8 as an effective coreceptor for HIV-1 and HIV-2 primary isolates [8] and interestingly we found that CCR8 could be frequently used (in addition to CCR5, CXCR4, or both), by HIV-1 and HIV-2 primary isolates. Noteworthy, the cellular and tissue distribution of CCR8 includes cells that are major targets for HIV infection, e.g. monocytes, thymocytes and CD4+ memory T-cells [67]-[71]. Thus, CCR8 usage does not necessarily implies a change in HIV cell tropism compared to CCR5 or CXCR4 usage. As a result of this expression pattern, and based on the significant proportion of HIV strains able to use CCR8 to enter target cells [8],[9],[14],[17],[51], we may considerer it as a potential alternative HIV coreceptor in vivo contributing to infection of natural target cells, at least under certain circumstances. This may be even more likely in HIV-2 since in this model the usage of cell receptors seems to be much more complex, as suggested by the identification of HIV-2 strains characterized by: (i) a CCR5/CXCR4-independent entry; (ii) a broader coreceptor usage compared to HIV-1; and (iii) a CD4-independent infection of host cells (reviewed in [72]-[74]).

The restricted use of CCR8 by HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 is an apparent paradox based on the general assumption that HIV-2 isolates have a broad profile of coreceptor usage [24]-[26],[75]. However, as a consequence of technical hindrance concerning in vitro HIV-2 isolation from asymptomatic aviremic patients, the majority of HIV-2 data regarding coreceptors usage has been derived from viruses obtained from patients in advanced disease stages, where more pathogenic variants with broader coreceptor usage could be present, leading to a bias in the viral population that was preferentially isolated. In contrast, HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 were isolated from two asymptomatic patients with undetectable viremia and normal T-CD4+ cell counts (1078 and 896 cells/mm3, respectively). Interestingly, another example of a CCR5/CXCR4-independent HIV-2 isolate was also obtained from an asymptomatic individual [32]. As referred, HIV-2 and HIV-1 infections are strikingly different during this period. At this early stage, HIV-2 infection resembles a natural long-term non-progressive infection as observed in those rare HIV-1 “elite controllers” [76],[77]. The reasons for this milder and less virulent infection are multi-factorial encompassing distinct mechanisms triggered by virus-host interactions, namely during cellular receptor’s engagement.

The data presented here reveal that in humans a persistent lentiviral infection could be maintained by variants that do not use CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptors. Similar observations have been reported in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) model, where some isolates have been described that do not use CCR5 to infect simian primary lymphocytes [78],[79]; instead, these isolates use alternative coreceptors such as CXCR6, GPR15 and CCR2b [78],[80],[81]. Coreceptors usage other than CCR5 and CXCR4 has been considered of limited importance for HIV infection in vitro and in vivo. Particularly, the use of CCR5 coreceptor seems to be a hallmark in HIV-1 pathogenesis and in human transmission (reviewed in [82]). The predominance of R5 strains throughout the asymptomatic stage and in some patients with more advanced disease, suggest that these variants may be more adapted to escape immune surveillance mechanisms or that they could infect long-lived cell reservoirs, providing long-lasting R5 viruses production. Additionally, it has been suggested that soon after sexual transmission only R5 viruses (or occasionally dual tropic viruses, R5X4) are transmitted, regardless the overall composition of initial inoculum (reviewed in [22],[83]). However, a recent observation revealed that a transmitted/founder HIV-1 was unable to use either CCR5 or CXCR4 to infect CD4+ cell lines and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [13]. Instead, alternate coreceptors (i.e. GPR15, APJ and FPRL-1) were efficiently used, emphasizing the notion that “rare” or “minor” coreceptors could be used in vivo in some circumstances or in some cell types, including at the time or soon after transmission to a new host. In HIV-2 no data exists regarding transmitted/founder viruses or the characteristics of viral dynamics during acute infection. It is conceivable that the same mechanisms proposed for HIV-1 could also be relevant in HIV-2 transmission. Unfortunately we could not obtain data regarding route and date of transmission nor sequential blood samples of the patients from which we isolated HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 in order to ascertain what would be the evolution of this viral population in vivo. Nevertheless, our present data, together with previous reports [7],[32] raise the possibility that, in vivo, CCR5 usage ability, required for an efficient in vivo infection, could be acquired, from an initial population of CCR5/CXCR4-independent viruses, in addition or in alternative to the initial receptors used.

In the second part of this study we mapped HIV-2 envelope glycoproteins determinants of CCR8 coreceptor usage, and the amino acids residues involved in coreceptor switch from R8 to R5 or R8 to R5X4. Our data provided the basis for some important conclusions, namely that: (i) the V1/V2 region contains the molecular determinants of coreceptor usage (e.g. CCR8, CCR5 and CCR5/CXCR4); (ii) several mutations are needed to convert a R8 isolate into a R5 or R5X4 variant; (iii) the replication kinetics is not affected by the mutations introduced in V1/V2 region.

In HIV-1, the V3 region of the envelope SU glycoprotein has been directly implicated as the major molecular determinant of coreceptor usage [33]-[37]. One of the major sequence signatures related to CXCR4 usage (alone or in addition to CCR5) seems to be a higher positive net charge of the V3 region. According to this “rule” a net charge equal to or higher than +6 is associated with CXCR4 usage [42],[84]-[86]. The ability to use the CXCR4 is also related with loss of a putative N-linked glycosylation (PNG) site within the V3 region [40]. Additionally to V3 region, structural studies of SU bound to cellular receptors (CD4 and chemokine receptor) revealed that V1/V2 region of SU glycoprotein is also involved in coreceptor binding, by directly cooperate with the V3 region [40]-[43],[87].

In the HIV-2 model, some studies had claimed an association between different coreceptor usage and specific sequence motifs within V3 region [44]-[47],[88]. All the proposed sequence motifs acting as determinants of coreceptor usage are located in the C-terminal half of the V3 region (aa-18 and aa-36 of V3 loop sequence) and apparently, a global V3 net charge above +6 and the substitution of valine or isoleucine at position 19 are associated with CXCR4 usage alone or in addition to CCR5 [45],[47]. However, other reports have failed to intersect the V3 amino acid sequence with coreceptor engagement, suggesting that no singular genetic signature could be proposed to explain different coreceptor usage [27],[48],[49].

Our data is the first to disclose the role of V1/V2 region in coreceptor engagement during initial HIV-2 interaction with host cell. In fact, using a panel of isogenic mutant viruses we demonstrate that the switch from R8 to R5 or R8 to R5X4 phenotype is determined by amino acids located in the base and tip of V1 and V2 loops. Interestingly, two of the mutations introduced two PNG sites both in the V2 loop. These two additional PNG sites are present in both R5 and R5X4 HIV-2MJC97 mutants but absent in the original R8 non-mutated virus. However, these two additional PNG sites did not alter the coreceptor usage (see MJC97mt4 in Figure 4A). There is scant information about the contribution of N-linked glycosylation in HIV-2 tropism and infectivity. However, as observed in HIV-1 [89], the influence of discrete PNG sites is probably context dependent and the same mutations could have different effects in tropism, depending on the overall Env structure and the molecular mechanism modulating binding to cellular receptors.

The way V1/V2 interacts with coreceptors, as well as the spatial organization of different Env structures and the conformational changes that they must undergo during receptor/coreceptor binding, are essentially unknown in HIV-2. Thus, any suggestions withdrawn from our results lack the direct supportive data already available for HIV-1 regarding Env glycoproteins structure in the trimeric native form [90],[91]. From these and other previous reports [92]-[97], several conclusions were made possible, the most important being that in HIV-1 the V1/V2 region, although not essential for viral entry is crucial to escape antibody-mediated neutralization [43],[98]-[103]. This protective role of V1/V2 region derives from the remarkable antigenic variability observed in this region, the presence of several PNG sites and the length variation of V1/V2 region. Due to structural interactions and rearrangements within the HIV-1 oligomeric Env glycoprotein, V1/V2 is also known to play a major role in conformational masking, creating a shield that protects other neutralization-sensitive domains either in the same SU glycoprotein, or in an adjacent SU subunit in the context of the trimeric Env spike complex [99]-[102].

In HIV-2, uncertainty prevails on which structural interactions and conformational dynamics must exist between different domains of trimeric Env glycoproteins. In addition, HIV-2 Env glycoproteins interactions with cell receptors seems to be much more complex and apparently less clear-cut than in HIV-1 (reviewed in [72]-[74]), and as supported by the present study, V1/V2 region could also directly and exclusively determine the coreceptor usage. To what extend the mechanisms described for HIV-1 are also dictating the tertiary and quaternary structure of HIV-2 envelope glycoproteins is not understood and neither are the precise contribution of V1/V2 and V3 regions in antibody-mediated neutralization in vivo [104]-[110]. However and worth noting, the V1/V2 region of HIV-2 has long been described as a target for neutralizing MAbs in vitro, and the influence of the overall conformation of this region (namely the amino acid composition at the base of the V2 loop) may affect the sensitivity to neutralization [59]; if we assume that this region also elicits host-neutralizing antibodies in vivo (as the RV144 vaccine trials against HIV-1 suggested [111]), and is simultaneously determinant for coreceptor engagement, this could constitute a major hindrance to HIV-2 effective replication and may help explain the low viremia and the higher and broader neutralizing capacity observed in sera from HIV-2 infected individuals [104],[105],[107]. Further studies using HIV-2 isolates obtained from asymptomatic individuals may provide further insights into factors associated with slow disease progression observed in HIV-2 infection.

Conclusions

In this article we clearly identify CCR8 as the exclusive coreceptor used by two primary isolates obtained from asymptomatic HIV-2 patients, instead of the widely referred CCR5 and CXCR4. In addition, we delved into the molecular interactions between surface envelope glycoprotein and this coreceptor and disclosed the amino acids residues that dictate the CCR8 usage. By site-directed mutagenesis we found that residues in the tip and base of V1/V2 region of surface glycoprotein are both necessary and sufficient to switch from CCR8 to CCR5 or to CCR5/CXCR4 usage.

Our study adds important new clues to the way HIV-2 envelope interacts with host-cells, and provides new insights into the molecular and structural dynamics underlying HIV-2 interaction with host cell coreceptors with direct implications in HIV-2 pathogenesis.

Methods

Cells and viruses

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), from HIV-uninfected donors, homozygous for wild-type ccr5 gene, were isolated, phytohemaglutinin (PHA)-stimulated and cultured as described [8]. PBMCs used in all experiments reported here were obtained from one single pool of different buffy-coats to avoid inter-individual variations in HIV infection susceptibility. CD8-depleted PBMCs were obtained from PBMCs after removal of CD8+ cells, using magnetic beads coated with anti-CD8 antibody as described [8].

Human osteosarcoma cell lines GHOST expressing CD4 and different coreceptors (GHOST-CD4/Hi5, GHOST-CD4/CCR8, GHOST-CD4/CX3CR1, GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CXCR4) were obtained through the National Institute of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. These GHOST cell lines were maintained as described earlier [8].

HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 primary isolates were obtained from PBMCs of infected patients by co-cultivation with PHA-stimulated PBMC. The isolation and initial characterization of HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 was previously reported [7],[49],[52]. Primary HIV-2ALI isolate [28],[30] was obtained from an early symptomatic patient (stage B2 according to CDC classification system for HIV infection). Two well-characterized laboratory strains, HIV-2ROD [112] and HIV-1Ba-L [113], both isolated from AIDS patients, were used in some experiments as controls. HIV-1Ba-L was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Primary HIV-2 viruses were only short-passaged in PHA-stimulated PBMCs cultured in RPMI medium as described [7]. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was determined by standard end-point dilution method (serial 10-fold dilutions in quadruplicate), using PBMC as target cells. Viral replication was monitored in culture supernatants by reverse transcriptase (RT) activity using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Lenti-RT kit, Cavidi).

Infectivity assays

Infectivity assays in PBMCs and GHOST cell lines were performed as described [7]. Briefly, cells were seeded into 24-well plates on the day prior to infection, at 1.5 × 105 cells/well. To assess chemokine usage, PBMCs and GHOST cell lines were inoculated with equal amounts of each virus (100 TCID50 in a final volume of 100 μl/well) and incubated for 3 h/37°C in the presence of 3 μg/ml of Polybrene. Cells were then washed and cultured in appropriate culture medium (500 μl/well). Viral replication was monitored in culture supernatants by RT activity by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Lenti-RT kit, Cavidi) during 12-day period after infection. Additionally, in some experiments, viral infection in GHOST cells was also monitored by LTR-driven GFP expression as described [7].

Susceptibility to CCRblockade

The chemokine I-309, specific for CCR8 [68],[71], was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 sensitivity to I-309 was based on the inhibition of viral production as described [7],[8]. Briefly, GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with blocking concentrations (100 ng/ml) of I-309 [51]. Viruses were then added as described in infectivity assays and incubated for 4 h in an inhibitor-containing medium. Cells were washed with PBS to remove unadsorbed viral particles and cultured in an appropriate medium either containing the referred concentration of I-309. Alternatively, these inhibition assays were also performed using CD8-depleted PBMCs as target cells, in order to avoid any uncontrolled inhibition exerted by soluble factors eventually secreted by CD8+ T-cells. Virus production was assessed by RT activity in culture supernatants as described in infectivity assays. Viral production in the absence of inhibitor was used as control.

In vitroadaptation experiments

The starting viruses for this study was obtained by transfection of 293 T cells with the pROD/MIC-SB and pROD/MJC-SB plasmids [52]. These plasmids contain an infectious HIV-2ROD provirus into which the env gene derived from both HIV-2MIC97 and HIV-2MJC97 isolates, was cloned [52]. The cells used in this experiment were the GHOST-CD4 cell lines individually expressing CCR8, CCR5 or CXCR4. An initial stock of each virus (ROD/MIC-SB and ROD/MJC-SB) was prepared by passing the virus-containing supernatants from transfected 293 T cells in GHOST-CD4/CCR8 cells. Each virus was then used to infect a 90:10 (%) mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 in the presence of 3 μg/ml of Polybrene. The infection of the 90:10 GHOST cells mixture was done by spinoculation in order to further enhance the efficiency of virus binding to target cell [114]. At day 12 after infection, culture supernatants were used to infect either a pure population of GHOST-CD4/CCR5 (or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4) cells, or an 80:20 mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 in the same conditions referred for initial 90:10 cell mixtures. Virus-containing supernatant from these latter cultures was again used to infect pure GHOST-CD4/CCR5 (or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4) or a 70:30 mixture of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 and GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4. This procedure was repeated using cell mixtures with increasing proportions of GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells, until a ratio 10:90 of GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CCR5 or GHOST-CD4/CCR8:GHOST-CD4/CXCR4 cells. At day 12 after infection, viral replication in each cell mixture was assessed by RT activity in culture supernatants.

Multi-site directed mutagenesis in the V1/V2 region of HIV-2MJC97

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to alter specific amino acid residues within V1/V2 region of HIV-2MJC97 SU envelope glycoprotein. Sequential mutations were introduced into plasmid pROD/MJC-SA which contains a HIV-2MJC97env fragment spanning from C1 to C4 region, inserted into genetic backbone of an infectious molecular clone of HIV-2ROD strain [52]. Sequential codon changes were made using a QuickChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit, (Stratagene) and mutagenic primers listed in Table 3, according to manufacturer’s protocol. The presence of the desired mutations was confirmed by sequencing the C1-C4 region of each mutant.

Virus particles were produced by transfecting 293 T cells with purified DNA from each mutated constructs, using FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions and as described [52]. Viral stocks of mutated viruses were prepared by passaging each viral-containing supernatants from transfected 293 T cells in IL2-stimulated PBMCs. The TCID50 of each viral stock was determined in PBMCs.

To assess replication competence and coreceptors usage of wild type or mutated viruses, PBMCs and GHOST cell lines were inoculated with titrated viral stocks according to the protocol described in “Infectivity assays” section.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Epi info version 6.04 (CDC, Atlanta, USA) and SPSS software version 10 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). The univariate analysis was tested using χ2 and 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test in case of small sample size. Statistical significance was assumed when p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

All healthy adult subjects (PBMC’s donors) provided written informed consent and validated by the Faculty of Pharmacy of Lisbon Institutional review board. None of the blood samples included in this study were gathered from infected patients.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results and methods of this article are available in the GenBank repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank); accession numbers: EU021092 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/EU021092), AF082339 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AF082339) and M15390 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/M15390).

Authors’ contributions

QSC carried out the experiments and analyzed data; MML analyzed data and performed the statistical analysis; MC helped in infectivity assays; JMAP designed the experiments and analyzed data; JMAP and QSC wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Clapham PR, McKnight A: Cell surface receptors, virus entry and tropism of primate lentiviruses. J Gen Virol. 2002, 83: 1809-1829.

Doms RW, Trono D: The plasma membrane as a combat zone in the HIV battlefield. Genes Dev. 2000, 14: 2677-2688.

Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA: CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996, 272: 1955-1958.

Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton RE, Hill CM, Davis CB, Peiper SC, Schall TJ, Littman DR, Landau NR: Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996, 381: 661-666.

Moore JP, Kitchen SG, Pugach P, Zack JA: The CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors°Central to understanding the transmission and pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004, 20: 111-126.

Zhang YJ, Dragic T, Cao Y, Kostrikis L, Kwon DS, Littman DR, KewalRamani VN, Moore JP: Use of coreceptors other than CCR5 by non-syncytium-inducing adult and pediatric isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is rare in vitro. J Virol. 1998, 72: 9337-9344.

Azevedo-Pereira JM, Santos-Costa Q, Mansinho K, Moniz-Pereira J: Identification and characterization of HIV-2 strains obtained from asymptomatic patients that do not use CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptors. Virology. 2003, 313: 136-146.

Calado M, Matoso P, Santos-Costa Q, Espirito-Santo M, Machado J, Rosado L, Antunes F, Mansinho K, Lopes MM, Maltez F, Santos-Ferreira MO, Azevedo-Pereira JM: Coreceptor usage by HIV-1 and HIV-2 primary isolates: the relevance of CCR8 chemokine receptor as an alternative coreceptor. Virology. 2010, 408: 174-182.

Cilliers T, Willey SJ, Sullivan WM, Patience T, Pugach P, Coetzer M, Papathanasopoulos M, Moore JP, Trkola A, Clapham PR, Morris L: Use of alternate coreceptors on primary cells by two HIV-1 isolates. Virology. 2005, 339: 136-144.

Deng HK, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR: Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997, 388: 296-300.

Edinger AL, Hoffman TL, Sharron M, Lee B, O’Dowd B, Doms RW: Use of GPR1, GPR15, and STRL33 as coreceptors by diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope proteins. Virology. 1998, 249: 367-378.

Gharu L, Ringe R, Bhattacharya J: Evidence of extended alternate coreceptor usage by HIV-1 clade C envelope obtained from an Indian patient. Virus Res. 2012, 163: 410-414.

Jiang C, Parrish NF, Wilen CB, Li H, Chen Y, Pavlicek JW, Berg A, Lu X, Song H, Tilton JC, Pfaff JM, Henning EA, Decker JM, Moody MA, Drinker MS, Schutte R, Freel S, Tomaras GD, Nedellec R, Mosier DE, Haynes BF, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Doms RW, Gao F: Primary infection by a human immunodeficiency virus with atypical coreceptor tropism. J Virol. 2011, 85: 10669-10681.

Lee S, Tiffany HL, King L, Murphy PM, Golding H, Zaitseva M: CCR8 on human thymocytes functions as a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptor. J Virol. 2000, 74: 6946-6952.

Neil SJD, Aasa-Chapman MM, Clapham PR, Nibbs RJ, McKnight A, Weiss RA: The promiscuous CC chemokine receptor D6 is a functional coreceptor for primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 on astrocytes. J Virol. 2005, 79: 9618-9624.

Pohlmann S, Krumbiegel M, Kirchhoff F: Coreceptor usage of BOB/GPR15 and Bonzo/STRL33 by primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1999, 80 (Pt 5): 1241-1251.

Shimizu N, Tanaka A, Oue A, Mori T, Ohtsuki T, Apichartpiyakul C, Uchiumi H, Nojima Y, Hoshino H: Broad usage spectrum of G protein-coupled receptors as coreceptors by primary isolates of HIV. AIDS. 2009, 27: 761-769.

Simmons G, Reeves JD, Hibbitts S, Stine JT, Gray PW, Proudfoot AE, Clapham PR: Co-receptor use by HIV and inhibition of HIV infection by chemokine receptor ligands. Immunol Rev. 2000, 177: 112-126.

Willey SJ, Reeves JD, Hudson R, Miyake K, Dejucq N, Schols D, de Clercq E, Bell J, McKnight A, Clapham PR: Identification of a subset of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus strains able to exploit an alternative coreceptor on untransformed human brain and lymphoid cells. J Virol. 2003, 77: 6138-6152.

Xiao L, Rudolph DL, Owen SM, Spira TJ, Lal RB: Adaptation to promiscuous usage of CC and CXC-chemokine coreceptors in vivo correlates with HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 1998, 12: F137-F143.

Islam S, Shimizu N, Hoque SA, Jinno-Oue A, Tanaka A, Hoshino H: CCR6 functions as a new coreceptor for limited primary human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e73116-

Keele BF, Estes JD: Barriers to mucosal transmission of immunodeficiency viruses. Blood. 2011, 118: 839-846.

Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM: Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999, 17: 657-700.

Guillon C, van der Ende ME, Boers PHM, Gruters RA, Schutten M, Osterhaus ADME: Coreceptor usage of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 primary isolates and biological clones is broad and does not correlate with their syncytium-inducing capacities. J Virol. 1998, 72: 6260-6263.

McKnight A, Dittmar MT, Moniz-Pereira J, Ariyoshi K, Reeves JD, Hibbitts S, Whitby D, Aarons EJ, Proudfoot AE, Whittle HC, Clapham PR: A broad range of chemokine receptors are used by primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 as coreceptors with CD4. J Virol. 1998, 72: 4065-4071.

Morner A, Björndal A, Albert J, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Inoue R, Thorstensson R, Fenyo EM, Björling E: Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates, like HIV-1 isolates, frequently use CCR5 but show promiscuity in coreceptor usage. J Virol. 1999, 73: 2343-2349.

Owen SM, Ellenberger D, Rayfield M, Wiktor S, Michel P, Grieco MH, Gao F, Hahn BH, Lal RB: Genetically divergent strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 use multiple coreceptors for viral entry. J Virol. 1998, 72: 5425-5432.

Azevedo-Pereira JM, Santos-Costa Q, Taveira N, Ver’ssimo F, Moniz-Pereira J: Construction and characterization of CD4-independent infectious recombinant HIV-2 molecular clones. Virus Res. 2003, 97: 159-163.

Liu HY, Soda Y, Shimizu N, Haraguchi Y, Jinno A, Takeuchi Y, Hoshino H: CD4-Dependent and CD4-independent utilization of coreceptors by human immunodeficiency viruses type 2 and simian immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 2000, 278: 276-288.

Reeves JD, Hibbitts S, Simmons G, McKnight A, Azevedo-Pereira JM, Moniz-Pereira J, Clapham PR: Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates infect CD4-negative cells via CCR5 and CXCR4: comparison with HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus and relevance to cell tropism in vivo. J Virol. 1999, 73: 7795-7804.

Willey SJ, Roulet V, Reeves JD, Kergadallan M-L, Thomas ER, McKnight A, Jégou B, Dejucq-Rainsford N: Human Leydig cells are productively infected by some HIV-2 and SIV strains but not by HIV-1. AIDS. 2003, 17: 183-188.

Sol N, Ferchal F, Braun J, Pleskoff O, Treboute C, Ansart I, Alizon M: Usage of the coreceptors CCR-5, CCR-3, and CXCR-4 by primary and cell line-adapted human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1997, 71: 8237-8244.

Cho MW, Lee MK, Carney MC, Berson JF, Doms RW, Martin MA: Identification of determinants on a dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein that confer usage of CXCR4. J Virol. 1998, 72: 2509-2515.

Hoffman TL, Doms RW: HIV-1 envelope determinants for cell tropism and chemokine receptor use. Mol Membr Biol. 1999, 16: 57-65.

Hoffman TL, Stephens E, Narayan O, Doms RW: HIV type I envelope determinants for use of the CCR2b, CCR3, STRL33, and APJ coreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95: 11360-11365.

Hu Q, Trent JO, Tomaras GD, Wang Z, Murray JL, Conolly SM, Navenot JM, Barry AP, Greenberg ML, Peiper SC: Identification of ENV determinants in V3 that influence the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization. J Mol Biol. 2000, 302: 359-375.

Smyth RJ, Yi Y, Singh A, Collman RG: Determinants of entry cofactor utilization and tropism in a dualtropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate. J Virol. 1998, 72: 4478-4484.

Cardozo T, Kimura T, Philpott SM, Weiser B, Burger H, Zolla-Pazner S: Structural basis for coreceptor selectivity by the HIV type 1 V3 loop. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007, 23: 415-426.

Fouchier RA, Groenink M, Kootstra NA, Tersmette M, Huisman HG, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H: Phenotype-associated sequence variation in the third variable domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 molecule. J Virol. 1992, 66: 3183-3187.

Pollakis G, Kang S, Kliphuis A, Chalaby MI, Goudsmit J, Paxton WA: N-linked glycosylation of the HIV type-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein as a major determinant of CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptor utilization. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 13433-13441.

Labrosse B, Treboute C, Brelot A, Alizon M: Cooperation of the V1/V2 and V3 domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 for interaction with the CXCR4 receptor. J Virol. 2001, 75: 5457-5464.

Nabatov AA, Pollakis GP, Linnemann T, Kliphius A, Chalaby MIM, Paxton WA: Intrapatient alterations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 V1V2 and V3 regions differentially modulate coreceptor usage, virus inhibition by CC/CXC chemokines, soluble CD4, and the b12 and 2G12 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2004, 78: 524-530.

Wyatt RT, Morales JP, Accola M, Desjardin E, Robinson JE, Sodroski JG: Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J Virol. 1995, 69: 5723-5733.

Albert J, Stalhandske P, Marquina S, Karis J, Fouchier RA, Norrby E, Chiodi F: Biological phenotype of HIV type 2 isolates correlates with V3 genotype. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996, 12: 821-828.

Isaka Y, Sato A, Miki S, Kawauchi S, Sakaida H, Hori T, Uchiyama T, Adachi A, Hayami M, Fujiwara T, Yoshie O: Small amino acid changes in the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 determines the coreceptor usage for CXCR4 and CCR5. Virology. 1999, 264: 237-243.

Shi Y, Brandin E, Vincic E, Jansson M, Blaxhult A, Gyllensten K, Moberg L, Broström C, Fenyo EM, Albert J: Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 coreceptor usage, autologous neutralization, envelope sequence and glycosylation. J Gen Virol. 2005, 86: 3385-3396.

Visseaux B, Hurtado-Nedelec M, Charpentier C, Collin G, Storto A, Matheron S, Larrouy L, Damond F, Brun-Vezinet F, Descamps D: Molecular Determinants of HIV-2 R5-X4 Tropism in the V3 Loop: development of a New Genotypic Tool. J Infect Dis. 2012, 205: 111-120.

Kulkarni S, Tripathy S, Agnihotri K, Jatkar N, Jadhav S, Umakanth W, Dhande K, Tondare P, Gangakhedkar R, Paranjape R: Indian primary HIV-2 isolates and relationship between V3 genotype, biological phenotype and coreceptor usage. Virology. 2005, 337: 68-75.

Santos-Costa Q, Parreira R, Moniz-Pereira J, Azevedo-Pereira JM: Molecular characterization of the env gene of two CCR5/CXCR4-independent human immunodeficiency 2 primary isolates. J Med Virol. 2009, 81: 1869-1881.

Gharu L, Ringe R, Satyakumar A, Patil A, Bhattacharya J: Short communication: evidence of HIV type 1 clade C env clones containing low V3 loop charge obtained from an AIDS patient in India that uses CXCR6 and CCR8 for entry in addition to CCR5. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011, 27: 211-219.

Horuk R, Hesselgesser J, Zhou Y, Faulds D, Halks-Miller M, Harvey S, Taub D, Samson M, Parmentier M, Rucker J, Doranz BJ, Doms RW: The CC chemokine I-309 inhibits CCR8-dependent infection by diverse HIV-1 strains. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273: 386-391.

Santos-Costa Q, Mansinho K, Moniz-Pereira J, Azevedo-Pereira JM: Characterization of HIV-2 chimeric viruses unable to use CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors. Virus Res. 2009, 142: 41-50.

Broder CC, Jones-Trower A: Coreceptor use by primate lentiviruses. Human Retroviruses and AIDS. Edited by: Kuiken CL, Foley P, Hahn B, Korber B, McCutchan F, Marx PA, Mellors JW, Mullins JI, Sodroski JG, Wolinsky SM. 1999, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, 517-541.

Ryan-Graham MA, Peden KW: Both virus and host components are important for the manifestation of a Nef- phenotype in HIV-1 and HIV-2. Virology. 1995, 213: 158-168.

Lee B, Ratajczak J, Doms RW, Gewirtz AM, Ratajczak MZ: Coreceptor/chemokine receptor expression on human hematopoietic cells: biological implications for human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 infection. Blood. 1999, 93: 1145-1156.

Lee B, Sharron M, Montaner LJ, Weissman D, Doms RW: Quantification of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 levels on lymphocyte subsets, dendritic cells, and differentially conditioned monocyte-derived macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999, 96: 5215-5220.

Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D: Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998, 72: 2855-2864.

de Wolf F, Meloen RH, Bakker M, Barin F, Goudsmit J: Characterization of human antibody-binding sites on the external envelope of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Gen Virol. 1991, 72 (Pt 6): 1261-1267.

McKnight A, Shotton C, Corbeil J, Jones I, Simmons G, Clapham PR: Location, exposure, and conservation of neutralizing and nonneutralizing epitopes on human immunodeficiency virus type 2 SU glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996, 70: 4598-4606.

Cilliers T, Nhlapo J, Coetzer M, Orlovic D, Ketas T, Olson WC, Moore JP, Trkola A, Morris L: The CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors are both used by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates from subtype C. J Virol. 2003, 77: 4449-4456.

Gorry PR, Dunfee RL, Mefford ME, Kunstman K, Morgan T, Moore JP, Mascola JR, Agopian K, Holm GH, Mehle A, Taylor J, Farzan M, Wang H, Ellery P, Willey SJ, Clapham PR, Wolinsky SM, Crowe SM, Gabuzda D: Changes in the V3 region of gp120 contribute to unusually broad coreceptor usage of an HIV-1 isolate from a CCR5 Delta32 heterozygote. Virology. 2007, 362: 163-178.

Jinno A, Shimizu N, Soda Y, Haraguchi Y, Kitamura T, Hoshino H: Identification of the chemokine receptor TER1/CCR8 expressed in brain-derived cells and T cells as a new coreceptor for HIV-1 infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998, 243: 497-502.

Rucker J, Edinger AL, Sharron M, Samson M, Lee B, Berson JF, Yi Y, Margulies BJ, Collman RG, Doranz BJ, Parmentier M, Doms RW: Utilization of chemokine receptors, orphan receptors, and herpesvirus-encoded receptors by diverse human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1997, 71: 8999-9007.

Isaacman-Beck J, Hermann EA, Yi Y, Ratcliffe S, Mulenga J, Allen SA, Hunter E, Derdeyn CA, Collman RG: Heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 Subtype C: Macrophage tropism, alternative coreceptor use, and the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization. J Virol. 2009, 83: 8208-8220.

Ohagen A, Devitt A, Kunstman KJ, Gorry PR, Rose PP, Korber BT, Taylor J, Levy R, Murphy RL, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D: Genetic and functional analysis of full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env genes derived from brain and blood of patients with AIDS. J Virol. 2003, 77: 12336-12345.

Singh A, Besson G, Mobasher A, Collman RG: Patterns of chemokine receptor fusion cofactor utilization by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants from the lungs and blood. J Virol. 1999, 73: 6680-6690.

Goya I, Gutiérrez J, Varona R, Kremer L, Zaballos A, Márquez G: Identification of CCR8 as the specific receptor for the human beta-chemokine I-309: cloning and molecular characterization of murine CCR8 as the receptor for TCA-3. J Immunol. 1998, 160: 1975-1981.

Roos RS, Loetscher M, Legler DF, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B: Identification of CCR8, the receptor for the human CC chemokine I-309. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 17251-17254.

Taylor JR, Kimbrell KC, Scoggins R, Delaney M, Wu L, Camerini D: Expression and function of chemokine receptors on human thymocytes: implications for infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2001, 75: 8752-8760.

Soler D, Chapman TR, Poisson LR, Wang L, Cote-Sierra J, Ryan M, Mcdonald A, Badola S, Fedyk E, Coyle AJ, Hodge MR, Kolbeck R: CCR8 expression identifies CD4 memory T cells enriched for FOXP3+ regulatory and Th2 effector lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006, 177: 6940-6951.

Tiffany HL, Lautens LL, Gao JL, Pease J, Locati M, Combadiere C, Modi W, Bonner TI, Murphy PM: Identification of CCR8: a human monocyte and thymus receptor for the CC chemokine I-309. J Exp Med. 1997, 186: 165-170.

Azevedo-Pereira JM, Santos-Costa Q, Moniz-Pereira J: HIV-2 infection and chemokine receptors usage - clues to reduced virulence of HIV-2. Curr HIV Res. 2005, 3: 3-16.

Azevedo-Pereira JM: HIV-2 interaction with target cell receptors, or why HIV-2 is less pathogenic than HIV-1. Current Perspectives in HIV Infection. Edited by: Saxena SK. 2013, InTech, Croatia, 411-445.

Reeves JD, Doms RW: Human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Gen Virol. 2002, 83: 1253-1265.

Bron R, Klasse PJ, Wilkinson D, Clapham PR, Pelchen-Matthews A, Power C, Wells TN, Kim J, Peiper SC, Hoxie JA, Marsh M: Promiscuous use of CC and CXC chemokine receptors in cell-to-cell fusion mediated by a human immunodeficiency virus type 2 envelope protein. J Virol. 1997, 71: 8405-8415.

Lambotte O, Boufassa F, Madec Y, Nguyen A, Goujard CEC, Meyer L, Rouzioux C, Venet A, Delfraissy J-FCCO: HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41: 1053-1056.

Deeks SG, Walker BD: Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity. 2007, 27: 406-416.

Chen Z, Kwon D, Jin Z, Monard S, Telfer P, Jones MS, Lu CY, Aguilar RF, Ho DD, Marx PA: Natural infection of a homozygous delta24 CCR5 red-capped mangabey with an R2b-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus. J Exp Med. 1998, 188: 2057-2065.

Riddick NE, Hermann EA, Loftin LM, Elliott ST, Wey WC, Cervasi B, Taaffe J, Engram JC, Li B, Else JG, Li Y, Hahn BH, Derdeyn CA, Sodora DL, Apetrei C, Paiardini M, Silvestri G, Collman RG: A novel CCR5 mutation common in sooty mangabeys reveals SIVsmm infection of CCR5-null natural hosts and efficient alternative coreceptor use in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6: e1001064-

Elliott STC, Riddick NE, Francella N, Paiardini M, Vanderford TH, Li B, Apetrei C, Sodora DL, Derdeyn CA, Silvestri G, Collman RG: Cloning and analysis of sooty mangabey alternative coreceptors that support simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmm entry independently of CCR5. J Virol. 2012, 86: 898-908.

Zhang Y, Lou B, Lal RB, Gettie A, Marx PA, Moore JP: Use of inhibitors to evaluate coreceptor usage by simian and simian/human immunodeficiency viruses and human immunodeficiency virus type 2 in primary cells. J Virol. 2000, 74: 6893-6910.

Alkhatib G: The biology of CCR5 and CXCR4. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009, 4: 96-103.

Grivel J-C, Shattock RJ, Margolis LB: Selective transmission of R5 HIV-1 variants: where is the gatekeeper?. J Transl Med. 2011, 9 Suppl 1: S6-

Briggs DR, Tuttle DL, Sleasman JW, Goodenow MM: Envelope V3 amino acid sequence predicts HIV-1 phenotype (co-receptor usage and tropism for macrophages). AIDS. 2000, 14: 2937-2939.

Delobel P, Nugeyre M-T, Cazabat M, Pasquier C, Marchou B, Massip P, Barre-Sinoussi F, Israël N, Izopet J: Population-based sequencing of the V3 region of env for predicting the coreceptor usage of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 1572-1580.

Lin NH, Becerril C, Giguel F, Novitsky V, Moyo S, Makhema J, Essex M, Lockman S, Kuritzkes DR, Sagar M: Env sequence determinants in CXCR4-using human immunodeficiency virus type-1 subtype C. Virology. 2012, 433: 296-307.

Kwong PD, Wyatt RT, Robinson JE, Sweet RW, Sodroski JG, Hendrickson WA: Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998, 393: 648-659.

Morner A, Thomas JA, Björling E, Munson PJ, Lucas SB, McKnight A: Productive HIV-2 infection in the brain is restricted to macrophages/microglia. AIDS. 2003, 17: 1451-1455.

Auwerx J, François K, Covens K, Van Laethem K, Balzarini J: Glycan deletions in the HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain compromise viral infectivity, sensitize the mutant virus strains to carbohydrate-binding agents and represent a specific target for therapeutic intervention. Virology. 2008, 382: 10-19.

Lyumkis D, Julien J-P, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Carragher B, Wilson IA, Ward AB: Cryo-EM structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013, 342: 1484-1490.

Julien J-P, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA: Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013, 342: 1477-1483.

Harris A, Borgnia MJ, Shi D, Bartesaghi A, He H, Pejchal R, Kang YK, Depetris R, Marozsan AJ, Sanders RW, Klasse PJ, Milne JLS, Wilson IA, Olson WC, Moore JP, Subramaniam S: Trimeric HIV-1 glycoprotein gp140 immunogens and native HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins display the same closed and open quaternary molecular architectures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108: 11440-11445.

Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S: Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008, 455: 109-113.

White TA, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, de la Cruz MJV, Nandwani R, Hoxie JA, Bess JW, Lifson JD, Milne JLS, Subramaniam S: Three-dimensional structures of soluble CD4-bound states of trimeric simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins determined by using cryo-electron tomography. J Virol. 2011, 85: 12114-12123.

Zanetti G, Briggs JAG, Grünewald K, Sattentau QJ, Fuller SD: Cryo-electron tomographic structure of an immunodeficiency virus envelope complex in situ. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2: e83-

Zhu P, Winkler H, Chertova E, Taylor KA, Roux KH: Cryoelectron tomography of HIV-1 envelope spikes: further evidence for tripod-like legs. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4: e1000203-

Zhu P, Liu J, Bess J, Chertova E, Lifson JD, Gris’ H, Ofek GA, Taylor KA, Roux KH: Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature. 2006, 441: 847-852.

Cao J, Sullivan N, Desjardin E, Parolin C, Robinson J, Wyatt R, Sodroski JG: Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997, 71: 9808-9812.

Stamatatos L, Cheng-Mayer C: An envelope modification that renders a primary, neutralization-resistant clade B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate highly susceptible to neutralization by sera from other clades. J Virol. 1998, 72: 7840-7845.

Pinter A, Honnen WJ, He Y, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Kayman SC: The V1/V2 domain of gp120 is a global regulator of the sensitivity of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates to neutralization by antibodies commonly induced upon infection. J Virol. 2004, 78: 5205-5215.

Rusert P, Krarup A, Magnus C, Brandenberg OF, Weber J, Ehlert A-K, Regoes RR, Günthard HF, Trkola A: Interaction of the gp120 V1V2 loop with a neighboring gp120 unit shields the HIV envelope trimer against cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Exp Med. 2011, 208: 1419-1433.

Saunders CJ, McCaffrey RA, Zharkikh I, Kraft Z, Malenbaum SE, Burke BP, Cheng-Mayer C, Stamatatos L: The V1, V2, and V3 regions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope differentially affect the viral phenotype in an isolate-dependent manner. J Virol. 2005, 79: 9069-9080.

Laakso MM, Lee F-H, Haggarty BS, Agrawal C, Nolan KM, Biscone MJ, Romano J, Jordan AP-O, Leslie GJ, Meissner EG, Su L, Hoxie JA, Doms RW: V3 loop truncations in HIV-1 envelope impart resistance to coreceptor inhibitors and enhanced sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3: e117-

De Silva TI, Aasa-Chapman MM, Cotten M, Hué S, Robinson JE, Bibollet-Ruche F, Sarge-Njie R, Berry N, Jaye A, Aaby P, Whittle HC, Rowland-Jones SL, Weiss RA: Potent autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses occur in HIV-2 infection across a broad range of infection outcomes. J Virol. 2012, 86: 930-946.

Kong R, Li H, Bibollet-Ruche F, Decker JM, Zheng NN, Gottlieb GS, Kiviat NB, Sow PS, Georgiev I, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Robinson JE, Shaw GM: Broad and potent neutralizing antibody responses elicited in natural HIV-2 infection. J Virol. 2012, 86: 947-960.

Marcelino JM, Borrego P, Rocha C, Barroso H, Quintas A, Novo C, Taveira N: Potent and broadly reactive HIV-2 neutralizing antibodies elicited by a vaccinia virus vector prime-C2V3C3 polypeptide boost immunization strategy. J Virol. 2010, 84: 12429-12436.

Ozkaya Sahin G, Holmgren B, da Silva ZJ, Nielsen J, Nowroozalizadeh S, Esbjornsson J, Månsson F, Andersson S, Norrgren H, Aaby P, Jansson M, Fenyo EM: Potent intratype neutralizing activity distinguishes human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) from HIV-1. J Virol. 2012, 86: 961-971.

Bjorling E, Broliden K, Bernardi D, Utter G, Thorstensson R, Chiodi F, Norrby E: Hyperimmune antisera against synthetic peptides representing the glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 can mediate neutralization and antibody-dependent cytotoxic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991, 88: 6082-6086.

Bjorling E, Chiodi F, Utter G, Norrby E: Two neutralizing domains in the V3 region in the envelope glycoprotein gp125 of HIV type 2. J Immunol. 1994, 152: 1952-1959.

Matsushita S, Matsumi S, Yoshimura K, Morikita T, Murakami T, Takatsuki K: Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against human immunodeficiency virus type 2 gp120. J Virol. 1995, 69: 3333-3340.

Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, Liao H-X, Devico AL, Lewis GK, Williams C, Pinter A, Fong Y, Janes H, DeCamp A, Huang Y, Rao M, Billings E, Karasavvas N, Robb ML, Ngauy V, de Souza MS, Paris R, Ferrari G, Bailer RT, Soderberg KA, Andrews C, et al: Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366: 1275-1286.

Clavel F, Gu Tard D, Brun-Vezinet F, Chamaret S, Rey MA, Santos-Ferreira MO, Laurent AG, Dauguet C, Katlama C, Rouzioux C: Isolation of a new human retrovirus from West African patients with AIDS. Science. 1986, 233: 343-346.

Gartner S, Markovits P, Markovitz DM, Kaplan MH, Gallo RC, Popovic M: The role of mononuclear phagocytes in HTLV-III/LAV infection. Science. 1986, 233: 215-219.

O’Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Malim MH: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol. 2000, 74: 10074-10080.

Acknowledgements