Abstract

Background

To identify baseline predictors of persisting pain in children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), relative to patients with JIA who had similar baseline levels of pain but in whom the pain did not persist.

Methods

We used data from the Research in Arthritis in Canadian Children emphasizing Outcomes (ReACCh-Out) inception cohort to compare cases of ‘moderate persisting pain’ with controls of ‘moderate decreasing pain’. Moderate pain was defined as a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain measurement score of > 3.5 cm. Follow-up was minimum 3 years. Univariate and Multivariate logistic regression models ascertained baseline predictors of persisting pain.

Results

A total of 31 cases and 118 controls were included. Mean pain scores at baseline were 6.4 (SD 1.6) for cases and 5.9 (1.5) for controls. A greater proportion of cases than controls were females (77.4% vs 65.0%) with rheumatoid factor positive polyarthritis (12.9% vs 4.2%) or undifferentiated JIA (22.6% vs 8.5%). Oligoarthritis was less frequent in cases than controls (9.7% vs 33%). At baseline, cases had more active joints (mean of 11.4 vs 7.7) and more sites of enthesitis (4.6 vs 0.7) than controls. In the final multivariate regression model, enthesitis count at baseline (OR 1.40, CI 95% 1.19–1.76), female sex (4.14, 1.33–16.83), and the overall Quality of My Life (QoML) baseline score (0.82, 0.69–0.98) predicted development of persisting pain.

Conclusions

Among newly diagnosed children with JIA with moderate pain, female sex, lower overall quality of life, and higher enthesitis counts at baseline predicted development of persisting pain. If our findings are confirmed, patients with these characteristics may be candidates for interventions to prevent development of chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pain in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) has been described as the most distressing component of the disease [1]. It may persist despite treatment, even in those whose arthritis has resolved [2]. Identifying predictors of persisting pain early in the course of the disease may enable better targeting of pain management interventions and hopefully prevent the development of persisting pain.

Two recent studies in children with JIA that used latent trajectory analysis [3] or group-based trajectory analysis [4] identified an uncommon persisting pain trajectory over 5 years. Shiff et al. referred to this as “chronically moderate pain” and reported its occurrence in 7.4% of patients [3]. Rashid et al. reported finding “consistently high pain” in 17.3% of JIA patients studied [4]. Both studies found many baseline clinical and demographic characteristics distinguishing these patients from those with minimal or low pain at baseline, but few characteristics could distinguish individuals in this “chronic, moderate, or high pain” group from patients who started with similar levels of pain but whose pain did not persist. The only baseline characteristics significantly associated with persisting pain were older age in the study by Shiff et al., and older age and higher baseline disability in the study by Rashid et al. [3, 4]. Although having Enthesitis-Related Arthritis (ERA), undifferentiated arthritis, or enthesitis regardless of JIA category have been associated with worse pain outcomes in other studies [5, 6], neither JIA category nor enthesitis were identified in these two studies as predictors of persisting pain.

Both Shiff et al. and Rashid et al. used probabilistic assignment of participants (i.e., each patient was estimated to contribute in different degrees to one or more trajectories, even if pain was measured only once or twice) [3, 4]. It is unclear whether this probabilistic assignment could be a factor contributing to the difficulty in distinguishing patients that develop persisting pain from those in whom pain decreased. We hypothesized that contrasting patients who clearly had documented persisting pain with those who clearly had documented decreasing pain in a case control study might be more fruitful.

We conducted a case–control study to identify baseline clinical or demographic predictors that distinguish children with JIA whose initial moderate pain becomes persistent from those whose initial moderate pain does not persist. Identifying predictors of persistent pain early in the course of disease may enable health care providers to target treatment and management interventions earlier. This is a key initial step in the prevention of pain 'chronification' in young people with JIA and has the potential for substantial, long term positive impact at the individual, institutional, and societal levels [7].

Methods

The Research in Arthritis in Canadian Children emphasizing Outcomes (ReACCh-Out) study methods have previously been reported [8]. In brief, children newly diagnosed with JIA were recruited at 16 Canadian centres between 2005 and 2010 and followed for up to 5 years. Patients were followed every 6 months for two years and then annually for up to 5 years. At each follow-up visit, pediatric rheumatologists reported clinical data and patients/parents completed questionnaires.

In the current study, cases were defined as children with JIA followed for a minimum of 3 years, who had at least moderate pain (VAS pain score > 3.5 cm) at baseline, at their final visit, and at least one interval visit [9]. Controls were defined as children with JIA followed for a minimum of 3 years, who had a VAS pain score > 3.5 cm at baseline that decreased to ≤ 3.5 cm from 12 months after diagnosis until the end of follow-up. This definition was chosen as it has been shown that most children with JIA on effective treatment attain inactive disease after approximately one year [10].

Arthritis-related pain intensity in the past week was measured using a validated 10 cm horizontal VAS (0 = no pain, 10 = very severe pain). Parents were instructed to obtain the pain score from their child if possible or to have the child complete the questionnaires themselves if they had the capacity to do so. Otherwise, parents provided pain scores on behalf of their child. Other patient-reported outcome measures included the Juvenile Arthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire (JAQQ, from 1 = best to 7 = worst) [11], the Quality of My Life questionnaire overall scale (QoML, 0 = worst, 10 = best) [12], the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (CHAQ, 0 = best, 3 = worst) [13] and the patient/parent global assessment (PPA; 0 = best, 10 = worst) [11]. These patient/parent-reported outcomes (PROs) are validated outcome measures well studied in the JIA population. The JAQQ measures health-related quality of life in children with JIA according to difficulties experienced in 4 domains (gross motor, fine motor, psychosocial, symptoms), while the QoML is a global self-reported quality of life scale [11, 12]. The CHAQ assesses physical disability in children with JIA and is an adaptation of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire [13].

Physician assessments included the number of active joints and enthesitis sites documented via 71-joint and 33-enthesitis homunculi. JIA category was assigned by the treating rheumatologist based on the ILAR criteria and confirmed via ReACCh-Out investigators [14]. Among multiple demographic variables collected at baseline in ReACCH-Out only age and sex were included in our study as there is literature supporting specific influence of these variables on the JIA pain experience and trajectory [3, 4, 15, 16].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous data were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD), and categorical data with absolute and relative frequencies (n and %). Univariate binomial logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI for the association of candidate baseline predictors with persisting pain. Among the data available in the ReACCh-Out cohort, the authors selected a limited set of candidate predictors based on previously reported associations [3,4,5,6], and the biopsychosocial model for chronic pain [17]. We were cautious to avoid the inclusion of too many variables in prediction models, relative to number of available cases. The predictors assessed were age at JIA onset, sex, JIA category, enthesitis count at baseline, active joint count at baseline, CHAQ, QoML, JAQQ, JAQQ psychosocial domain, and PPA. JAQQ item 14 “felt depressed” and item 16 “felt sad” were considered individually in exploratory analyses, as there is evidence that patients with JIA and depressive symptoms experience more pain, and no validated depression scales were available in the ReACCh-Out dataset [18]. Variables with p ≤ 0.2 from the univariate logistic regression were considered for the multivariate logistic regression model.

Results

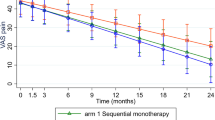

Among 1497 children with JIA enrolled in the ReaCCh-Out cohort, 663 were followed for at least 3 years. Among these 663 participants, 227 (34.2%) of those had a pain VAS > 3.5 cm at baseline and 31 (4.7%) met criteria as cases and 118 (17.8%) as controls for the current study. Some potential cases and controls did not meet the inclusion criteria due to missing pain scores. Baseline characteristics of cases and controls are shown in Table 1; and pain scores over time for cases versus controls are shown in Fig. 1.

Box Plot of Pain Scores Over Time in Children with Persisting Pain (Cases) Versus those with Decreasing Pain (Controls). The length of the box represents the interquartile range (the distance between the 25th and 75th percentiles). The circle within the box represents the control group mean and the cross within the box represents the case group mean. The horizontal line within the box represents the group median. The vertical lines, or ‘whiskers’, are drawn to the most extreme points in the group that lie within the fences. The upper fence is defined as the third quartile (represented by the upper edge of the box) plus 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). The lower fence is defined as the first quartile (represented by the lower edge of the box) minus 1.5 times the interquartile range. Visit N = visit number. Visit 1 = initial visit, visit 2 = 6-month visit, visit 3 = 12-month visit, visit 4 = 18-month visit, visit 5 = 2-year visit, visit 6 = 3-year visit, visit 7 = 4-year visit, visit 8 = 5-year visit

A greater proportion of cases than controls were female (77.4% vs 65.0%) with rheumatoid factor positive polyarthritis (12.9% vs 4.2%) or undifferentiated JIA (22.6% vs 8.5%). Oligoarthritis was less frequent in cases (9.7% vs 33%). Cases had a higher mean active joint count (11.4 vs 7.7) and more sites of enthesitis (4.6 vs 0.7) at baseline. A baseline enthesitis count was not entered in 64 patients: in 48 of these, it was stated that enthesitis was not applicable. Since none of these patients had any sites of enthesitis marked on the homunculus, a value of zero was assumed.

Baseline predictors associated with persisting pain are shown in Table 2.

A higher enthesitis count (OR 1.30, CI 95% 1.12–1.56, p = 0.002), lower quality of life as measured by QoML (0.85, 0.72–0.99, p = 0.03), and higher PPA at baseline (1.25, 1.06–1.48, p = 0.01) were all statistically associated with a child having moderate persisting pain in univariate analyses. In multivariate logistic regression with baseline QoML score, PPA, enthesitis count, and sex as covariates, PPA was no longer statistically significant and was therefore removed from the final model. In the final, parsimonious multivariate logistic regression model, a higher baseline enthesitis count (OR 1.40, CI 95% 1.19–1.76; p = 0.0005), female sex (4.14, 1.33–16.83; p = 0.03), and lower baseline QoML (0.82, 0.69–0.98, p = 0.02) were statistically significant predictors that distinguished cases (persisting pain) from controls (decreasing pain).

Discussion

This case–control study assessed baseline variables that distinguish children with JIA with persisting moderate pain from those whose pain improved despite similar levels of baseline pain. In a final parsimonious model, we found that female sex, higher number of enthesitis sites and lower QoML at baseline were significantly associated with persisting pain.

The association of female sex with persisting musculoskeletal pain has been previously reported [19]. Higher pain levels have also been associated with female sex in JIA specifically [15, 16]. Interestingly, Shiff’s study found that although female sex clearly distinguished trajectories of persisting moderate pain from minimal pain, it did not distinguish persisting from improving pain [3].Similarly, Rashid et al. did not find that female sex was a factor contributing to persistence of pain [4]. Of note, whereas both Shiff and Rashid found older age at JIA onset was a factor in the development of persistent pain, age did not emerge as a significant factor in our study. The reason for this variation is yet unclear and underscores the importance of future research into the role of age as a predictor of persistent pain in JIA.

Baseline enthesitis count was the strongest predictor of persisting pain in our study. Shiff et al. found no association with presence of enthesitis but did not assess the enthesitis count (i.e. the number of entheseal sites that were tender on exam) [3]. Rashid et al. did not assess enthesitis per se but noted increased frequency of ERA in children with persisting pain [4]. Support for the deleterious effects of enthesitis on pain intensity and quality of life for children with JIA has been shown in previous studies and this factor should be included in future investigations [5, 6]. We hypothesize that more widespread and severe disease (with more diffuse enthesitis) may have more impact on central mechanisms that maintain pain. It is also possible that mechanisms underlying prolonged pain, including central sensitization and lower pain pressure threshold, may lead to allodynia and hyperalgesia [20]. This may result in a falsely elevated enthesitis site count found by the detecting clinician.

The association of poor patient-reported outcomes (i.e. poorer self or parent assessed overall health status and quality of life and others) with higher pain intensity in children with JIA has been reported in several studies [4, 21,22,23]. Given that both cases and controls started with similar levels of pain, it is possible that a lower self-perceived quality of life at similar pain intensities is acting as an indicator of distress or catastrophizing, but we did not have validated measure of distress or catastrophizing to investigate directly. In the literature, quality of life appears to be a broad and individualized construct, only partially affected by health status [12]. Seid et al. demonstrated that multiple non-medical factors contribute to a child’s quality of life scores, including self-efficacy, coping, barriers to adherence, social support, parental distress, and access to care [24]. These factors were not measured in this study, therefore it is difficult to ascertain the reasons for lower baseline quality of life in the cases versus the controls. We suspect each case’s unique biological, psychological, and social experiences contributed to varying degrees. Future studies more broadly examining the role of these additional factors in the development of persistent pain in JIA would be extremely pertinent and valuable.

Major strengths of this study include the longitudinal data collection, the documented, rather than probability assigned pain trajectory, the use of validated measures of pain and other PROs, and the national scope of the study. Our study has several limitations. First, the number of cases was small, due in part to missing pain score data. Nonetheless, it was telling that despite ReACCh-Out being the largest prospective cohort of children with JIA when first published in 2015, we could only confirm the presence of moderate persisting pain in 31 (< 5%) of eligible subjects. Second, clinical assessment of enthesitis is subjective and there may be non-JIA reasons for tenderness over entheseal locations. Third, the pain VAS in our study could be completed by either the child or the parent. Considering that previous research found just 71% agreement between child and parent on this question, the potential for overestimation or underestimation of the child’s pain score must be considered [25]. Fourth, we could only study the potential predictors that were measured in the ReACCh-Out cohort. Factors that influence a child’s pain experience (such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, pain catastrophizing, pain interference, and parental distress) were not assessed in this cohort. Lastly, genetic, epigenetic, physical, and social environmental factors that could influence neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to pain persistence were also not assessed [7].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that among children with JIA who had moderate pain at baseline, female sex, lower overall quality of life, and higher number of enthesitis sites at baseline were associated with the development of persisting pain. Further research is needed to support these preliminary findings. If our findings are confirmed, children with these characteristics may benefit from a pain management focus early in their course of treatment. Timely implementation strategies to prevent pain ‘chronification’ in those at risk may ease the burden of chronic pain in children with JIA, which may ultimately have lifelong, far-reaching benefits.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHAQ:

-

Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- ERA:

-

Enthesitis-Related Arthritis

- ILAR:

-

International League of Associations for Rheumatology

- JAQQ:

-

Juvenile Arthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire

- JIA:

-

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- PPA:

-

Patient/Parent Global Assessment

- PROs:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes

- QoML:

-

Quality of My Life Questionnaire

- ReACCh-Out:

-

Research in Canadian Children Emphasizing Outcomes

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid Factor

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis System

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale

References

Östlie IL, Johansson I, Möller A. Struggle and adjustment to an insecure everyday life and an unpredictable life course. Living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis from childhood to adult life – an interview study. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(8):666–74.

Bromberg MH, Connelly M, Anthony KK, Gil KM, Schanberg LE. Self-reported pain and disease symptoms persist in juvenile idiopathic arthritis despite treatment advances: an electronic diary study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):462–9.

Shiff NJ, Tupper S, Oen K, Guzman J, Lim H, Lee CH, et al. Trajectories of pain severity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Research in Arthritis in Canadian Children Emphasizing Outcomes cohort. Pain. 2018;159(1):57–66.

Rashid A, Cordingley L, Carrasco R, Foster HE, Baildam EM, Chieng A, et al. Patterns of pain over time among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(5):437–43.

Rumsey DG, Guzman J, Rosenberg AM, Huber AM, Scuccimarri R, Shiff NJ, et al. Children with enthesitis have worse quality of life, function, and pain, irrespective of their juvenile arthritis category. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(3):441–6.

Taxter AJ, Wileyto EP, Behrens EM, Weiss PF. Patient-reported outcomes across categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(10):1914–21.

Borsook D, Youssef AM, Simons L, Elman I, Eccleston C. When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain. 2018;159(12):2421–36.

Guzman J, Oen K, Tucker LB, Huber AM, Shiff N, Boire G, et al. The outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in children managed with contemporary treatments: results from the ReACCh-Out cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(10):1854–60.

Hirschfeld G, Zernikow B. Cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the VAS for children and adolescents: what can be learned from 10 million ANOVAs? Pain. 2013;154(12):2626–32.

Sengler C, Klotsche J, Niewerth M, Liedmann I, Föll D, Heiligenhaus A, et al. The majority of newly diagnosed patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis reach an inactive disease state within the first year of specialised care: data from a German inception cohort. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e000074.

Duffy CM, Arsenault L, Duffy KN, Paquin JD, Strawczynski H. The Juvenile Arthritis Quality of life Questionnaire–development of a new responsive index for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile spondyloarthritides. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(4):738–46.

Feldman BM, Grundland B, McCullough L, Wright V. Distinction of quality of life, health related quality of life, and health status in children referred for rheumatologic care. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):226–33.

Singh G, Athreya BH, Fries JF, Goldsmith DP. Measurement of health status in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(12):1761–9.

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–2.

Schanberg LE, Gil KM, Anthony KK, Yow E, Rochon J. Pain, stiffness, and fatigue in juvenile polyarticular arthritis: contemporaneous stressful events and mood as predictors. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1196–204.

Benestad B, Vinje O, Veierød MB, Vandvik IH. Quantitative and Qualitative Assessments of Pain in Children with Juvenile Chronic Arthritis Based on the Norwegian Version of the Pediatric Pain Questionnaire. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(5):293–9.

Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):581–624.

Hanns L, Cordingley L, Galloway J, Norton S, Carvalho LA, Christie D, et al. Depressive symptoms, pain and disability for adolescent patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(8):1381–9.

Sperotto F, Brachi S, Vittadello F, Zulian F. Musculoskeletal pain in schoolchildren across puberty: a 3-year follow-up study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13(1):16.

Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(Suppl 3):S2–15.

Tupper SM, Rosenberg AM, Pahwa P, Stinson JN. Pain intensity variability and its relationship with quality of life in youths with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(4):563–70.

Sawyer MG, Whitham JN, Roberton DM, Taplin JE, Varni JW, Baghurst PA. The relationship between health-related quality of life, pain and coping strategies in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(3):325–30.

Dhanani S, Quenneville J, Perron M, Abdolell M, Feldman BM. Minimal difference in pain associated with change in quality of life in children with rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(5):501–5.

Seid M, Huang B, Niehaus S, Brunner HI, Lovell DJ. Determinants of health-related quality of life in children newly diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(2):263–9.

Lal SD, McDonagh J, Baildam E, Wedderburn LR, Gardner-Medwin J, Foster HE, et al. Agreement between proxy and adolescent assessment of disability, pain, and well-being in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2011;158(2):307–12.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to the children and families that participated in this study and to the following additional members of the ReACCh-Out study: Susanne Benseler, Roberta Berard, Gilles Boire, Roxana Bolaria, David Cabral, Bonnie Cameron, Sarah Campillo, Mercedes Chan, Gaëlle Chédeville, Anne-Laure Chetaille, Paul Dancey, Jean Dorval, Ciarán Duffy, Janet Ellsworth, Brian Feldman, Debbie Feldman, Katherine Gross, Ellie Haddad, Kristin Houghton, Adam Huber, Nicole Johnson, Roman Jurencak, Bianca Lang, Maggie Larché, Ronald Laxer, Claire LeBlanc, Deborah Levy, Nadia Luca, Paivi Miettunen, Kimberly Morishita, Kiem Oen, Ross Petty, Suzanne Ramsey, Alan Rosenberg, Johannes Roth, Claire Saint-Cyr, Heinrike Schmeling, Rayfel Schneider, Earl Silverman, Lynn Spiegel, Elizabeth Stringer, Rosie Scuccimarri, Shirley Tse, Stuart Turvey, Karen Watanabe Duffy, and Rae Yeung. Special thanks to Michele Gibbon and the research assistants at each center for the organization and coordination of the ReACCh-Out project.

Funding

The statistical analysis was financially supported by Women’s and Children’s Health Research Institute at the University of Alberta through a Resident/Trainee Research Grant. The ReACCh-Out study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (QNT 69301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

TM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this project, interpreted the data and drafted the work. DR and JG made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this project, interpreted the data and substantially revised the work. LT and NJS made substantial contributions to the concept and design of this work, participated in data acquisition for the registry and substantially revised it. ST made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and substantially revised it. MY made substantial contribution to data analysis. All authors have approved the submitted version and agreed to be accountable for all contributions, ensuring accuracy and integrity of all parts of the work and the resolution documented.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board (Pro00078429).

The need for consent was waived due to data being extracted from an established, anonymized database. The Research in Arthritis in Canadian Children emphasizing Outcomes (ReACCH-Out) database will be accessed with permission. This database contains cohort data for children newly diagnosed with JIA from 2005–2010 who were followed for up to 5 years. The data belongs to the Canadian Alliance of Paediatric Rheumatology Investigators and appropriate approval has been attained for access.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There has been no financial support or other benefits from commercial sources for the work reported on in this manuscript. NJS is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and owns Abbvie, Gilead, Iovance stock. The other authors have no financial interests which could create a potential conflict of interest or the appearance of a conflict of interest regarding the work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

McGrath, T., Guzman, J., Tucker, L. et al. Predictors of persisting pain in children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: a case control study nested in the ReACCh-Out cohort. Pediatr Rheumatol 21, 102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00885-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00885-w