Abstract

Background

Seasonal influenza virus vaccination should be considered in all pediatric patients with rheumatic diseases. Few studies have addressed influenza vaccination safety and efficacy in this group. We aim to prospectively evaluate immunogenicity and safety of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine including A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B strains in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) receiving biological therapy.

Methods

Thirty-five children diagnosed with JIA and 6 healthy siblings were included. Serum samples were collected prior to, 4-8 weeks and one year after vaccination. Microneutralization assays were used to determine neutralizing antibody titers. The type and duration of therapy were analyzed to determine its effect on vaccine response. Clinical data of the participants were collected throughout the study including severe adverse events (SAE) and adverse events following immunization (AEFI).

Results

Twenty-five patients (74.3%) received biological treatment for JIA; anti TNF-α was prescribed in 15, anti IL-1 receptor in 4 and anti IL-6 receptor therapy in 6 children. The seroprotection rate 4-8 weeks after vaccination in the JIA group was 96% for influenza A/(H1N1)pdm and influenza A/H3N2, and 88% for influenza B. No differences were found in GMT, seroprotection and seroconversion rates for the three influenza strains between the control group and patients receiving biological therapy. Furthermore, long-term seroprotection at 12 months after vaccination was similar in patients receiving either biological or non-biological treatments. No SAEs were observed.

Conclusions

In this study, influenza vaccination was safe and immunogenic in children with JIA receiving biological therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Children and adolescents with rheumatic diseases (RD) are at increased risk of infection compared to age- and gender-matched subjects without RD due to their aberrant immunity and frequent use of immunosuppressive drugs [1]. Annual vaccination against influenza is recommended for immunocompromised patients [2]. Efficacy and safety of vaccination remain to be defined in rheumatologic patients with immunomodulatory therapy, including high doses of steroids. Recommendations for vaccination in pediatric patients with RD were published in 2011 by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). Seasonal influenza virus vaccination should be considered in all pediatric patients with RD [3, 4]. Few studies have addressed influenza vaccination safety and efficacy in this group, most of which have small sample sizes, include a wide variety of rheumatic diseases and have scarce data on new biological therapies [3,4,5,6].

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common inflammatory rheumatic chronic disease of childhood, with a prevalence of approximately 1 per 1000. JIA is defined as arthritis of unknown etiology beginning prior the age of 16 years persisting for at least 6 weeks with other known conditions excluded [7]. The incidence of influenza infection in this patient group is unknown and evidence is lacking whether children with JIA have an increased risk of severe influenza infection or its associated complications. However, influenza virus can trigger disease flare, treatment interruption and the use of antibiotic therapy for suspected bacterial co-infection, all of which are associated with unnecessary medical revisions, thus reducing the quality of life of these children and their families [8]. The development of therapeutic biological agents including anti IL-6 and anti IL-1 receptor (R) therapy, has markedly altered treatment strategies for RD and greatly improved the prognosis of affected individuals [9]. Whilst influenza vaccination in children with RD receiving non biological immunosuppressive agents results in similar serum antibody titers compared to those of healthy children, few data exist on the impact of biological therapy [10]. Here, we describe the immunogenicity and safety of influenza vaccination and long term seroprotection on a pediatric cohort diagnosed with JIA receiving immunomodulatory therapy including anti IL-6 and anti IL-1R therapy and review the published literature.

Methods

Patient inclusion

We performed a prospective, longitudinal study of children with JIA receiving the influenza vaccine in two consecutive influenza seasons 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 at the University Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville. Diagnosis of JIA was made according to the recommendations of the International League of Associations for Rheumatology [7]. Patients (aged 1-18 years) and healthy siblings, as controls, were included once and consecutively after the legal guardians signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria for this study included acute infection at the time of vaccination, history of previous adverse reaction or anaphylaxis to chicken egg protein or any other vaccine, demyelinating disease or parents refusing to sign the informed consent. The Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of the local Hospital approved the study.

Samples

Serum samples were collected from each patient at the time of vaccination (baseline), at 4-8 weeks post vaccination (Tpv) and one year after vaccination (before the new seasonal vaccine immunization). Samples were stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Clinical and laboratory data

Demographic data, including sex, age, time of diagnosis, JIA subtype, type of treatment, previous influenza vaccination, date of vaccination, activity of disease using the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS) including 4 criteria (physician global assessment of disease activity, parent/patient global assessment of well-being, active joint count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), full blood count, immunoglobulin levels, Rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), immunological and clinical response were collected [11]. Patients diagnosed with JIA were stratified according to the treatment received at time of vaccination (biological treatment and non-biological treatment including methotrexate (MTX) only or no treatment).

Safety assessment

Patients were followed-up during a six-month period to collect and record adverse events following immunization (AEFI). International guidelines for AEFI reporting and causality assessment were used according to the WHO, Global Vaccine Safety Initiative (GVSI) [12]. AEFI were monitored using a questionnaire given to patients on the vaccination day, and every 3 months in the follow-up visits, whilst serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events of special interest (AESI) were actively monitored during trial duration. AESI included were flare and worsening of the JADAS [11]. A flare was defined as a worsening of 40% in at least 2 of the 6 disease activity parameters of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) pediatric core set, without a simultaneous improvement of 30% or more in at least 2 of the remaining parameters [13].

Vaccines

Patients received one dose of the trivalent non-adjuvanted inactivated vaccine in 2013/2014 (Sanofi, Sanofi- Pasteur MSD) containing the following strains: influenza A/California/7/2009-H1N1 (A/(H1N1)pdm), influenza A/Victoria/361/2011-H3N2 (A/H3N2) and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 and in 2014/2015 containing the following strains: A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm; A/Texas/50/2012 (H3N2); B/Massachusetts/2/2012. Children under the age of nine, who were vaccinated for the first time against influenza, received a second dose of vaccine after one month.

Microneutralization assay

As described previously [14], two-fold serial dilutions of the inactivated human sera (from 1:5 to 1:2560) were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.25 for A/(H1N1)pdm, 1.4 MOI for A/H3N2, and 0.05 MOI for B. Four wells with infected cells were used as positive controls and wells with only cells were used as negative controls. One hundred microliters containing 1.5 × 105 Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells/ml were added to each well of a 96-well dish and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Primary antibodies for influenza A nucleoprotein (Anti-Influenza A nucleoprotein Bioporto Bionova, Gentofte, Denmark) diluted 1:1500 or influenza B nucleoprotein (Anti-Influenza B nucleoprotein Bioporto from Bionova, Gentofte, Denmark) diluted 1/1000 were used, followed by a HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody diluted 1:1000 (Sigma-Aldrich). One-hundred microliters of peroxidase substrate (3, 3′, 5, 5′-Tetramethyl-benzidine substrate, supersensitive, for ELISA; Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each well and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The average absorbance (A450) from the quadruplicate wells of virus-infected (VC) and uninfected (CC) control wells was determined, and the neutralizing endpoint was determined by using a 50% specific signal calculation. The endpoint titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum with A450 value less than X, where X = [(average A450 of VC wells) - (average A450 of CC wells)]/2 [14]. Sera were considered positive if titers were ≥40 obtained in at least two independent assays. Vaccination immunogenicity parameters were based on the following international EMEA/CPMP 1997 criteria described for the hemagglutination inhibition assay, which have shown correlation with antibody titres measured by microneutralization assay [15, 16]. Seroprotection was considered as a post-vaccination serum antibody titer >1:40. Seroconversion was considered when a 4-fold antibody titer increase from baseline was achieved. Geometric mean titers (GMT) defined as mean antibody titer in the group of vaccinated individuals; seroprotection rate defined as the proportion of vaccinated individuals with antibody titers ≥1:40; seroconversion rate as the percentage of subjects showing seroconversion; and geometric mean ratio (GMR) defined as seroconversion factor post to prevaccination.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed. Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range or mean ± standard deviation if adjusted to normal distribution, and evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests when appropriate. The main primary outcome for the analysis was seroprotection. Secondary outcomes were seroconversion, GMT after vaccination, and safety. For bivariate analysis, the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test or the McNemar test were used for categorical variables. For quantitative variables, the Mann-Whitney test or Student’s t test were used. If the variance was not homogeneous the Welch test was applied, in case of homogeneity of variances, ANOVA was applied.

For immunogenicity analysis, GMT at each time point was used. Relative risk and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated by taking the exponent of natural logarithm of the mean and 95% CI. Results were analyzed by PASW Statistic 18.0.1 software. Statistical significance was established as a p value of <0.05. All reported p values were based on two-tailed tests. Bivariate analysis was an exploratory outcome and adjustment for multiplicity was done for this analysis using the Bonferroni method (adjusted p value <0.002).

Results

Patient cohort

Baseline clinical parameters and demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. A total of 41 subjects were included in the study. Three patients received two vaccine doses. 35 (83.3%) patients were diagnosed with JIA (experimental group), median age of 10.6 years (IQR 8.8-12.7), 12 (35.3%) were male and 25 (74.3%) were receiving biological treatment for JIA; 15 patients anti-TNFα (11 etanercept and 4 adalimumab), 4 anti-IL-1R (anakinra) and 6 anti-IL-6R (tocilizumab). Six (14.2%) children were healthy individuals (control group), with a median age of 11.6 years (IQR 9.8-14.6) and two (33.3%) male.

Immunological response to influenza vaccination

Overall, control and experimental, groups together achieved an adequate seroprotection rate at Tpv: 97.8% for influenza A/(H1N1)pdm, 95.6% for influenza A/H3N2 and 91.1% for influenza B. Median Tpv was 5.4 weeks IQR (4.6-6.1). Immunological response to vaccination was analyzed in the experimental group and compared with the control group. No differences were found in GMT, seroprotection and seroconversion rates at Tpv for the three influenza strains (A/(H1N1)pdm, A/H3N2 and B) (Table 2). Children diagnosed with JIA were stratified according to receiving biological treatment and again no differences were observed in the antibody response to vaccination based on treatment (Table 2). There were no differences for A/(H1N1)pdm and A/H3N2 postvaccination seroprotection rates between children receiving biological treatment and those receiving no biological therapy (96% vs. 100%; p = 0.521); neither for influenza B strain (88% vs. 90%; p = 0.867). Similarly, receiving biological treatment was not associated with differences in the post-vaccination GMT or in seroconversion for the three vaccine strains. Two of the patients receiving biological treatment had concomitant systemic steroids, however no differences were found in pre- or post-vaccination seroprotection or antibody titers compared with patients on biological treatment with no steroids.

Within the experimental group, patients were stratified according to the type of biological treatment and no differences were found in the antibody response against the three influenza strains (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Three children received two vaccine doses and showed, post-vaccination seroprotection after the second dose, however antibody titers did not differ from those receiving one dose only (data not shown).

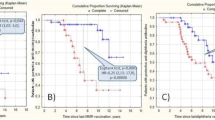

Long-term seroprotection rates after vaccination

In the JIA group 12 individuals had serum samples available one year after vaccination, six (50%) of them received biological treatment, and long-term seroprotection after vaccination was analyzed. Overall no differences in humoral responses were observed for the three strains analyzed. All 12 patients (100%) were seroprotected at Tpv vs. 91.7% one year after vaccination against A(H1N1)pdm (p = 0.327); 81.8% vs. 91.7% were protected against A/H3N2 (p = 0.070), and 91.7% vs. 91.7% (p = 0.500) against influenza B at Tpv vs. one year after vaccination.

Similarly, the type of treatment (biological or non-biological) did not influence long-term antibody response. In patients with biological treatment (n = 6), seroprotection at one-year post vaccination was 100% (100% at Tpv) for influenza A/H1N1 (p = 0.999), 66.7% (83.3% at Tpv) for H3N2 (p = 0.999) and 100% (100% at Tpv) for influenza B (p = 0.999).

Bivariate analysis

The analysis of confounding factors associated with antibody response to vaccination in patients with JIA (Additional file 2: Table S2), revealed seroprotected patients to Tpv A/H1N1 to have lower platelet levels and ESR at baseline compared with non-seroprotected individuals (286 vs. 594 × 10 [9]/L, p = 0.001 and 7.2 vs 18 mm/h, p = 0.009). When adjusted for multiplicity (p < 0.002), only platelet level was significantly lower in seroprotected patients to Tpv for A/H1N1.

Safety of influenza vaccination

There was no follow-up loss of any of the subjects in the study. Overall no SAEs were observed. Seven out of 41 (17%) children showed adverse drug local reactions (six with local skin inflammation and one hematoma), whilst two out of 41 (4.9%; one each in the control and biological therapy group) had systemic adverse drug reactions (general malaise and fever >24 h). During the 6-month follow-up, 16 febrile episodes, not related to vaccination, were reported in 11 patients (four in the non-biological and seven in the biological therapy group), 10 of which were treated with oral antibiotic therapy. JADAS score increased in 6 patients at Tpv compared with baseline, in three of them from a low or no activity to moderate [17]. However, none of them had a flare based on the mentioned criteria [13].

Discussion

In this cohort of children with JIA receiving immunomodulatory therapy, influenza vaccination was safe and immunogenic; and the neutralizing antibody response was independent of the type of treatment. To date few influenza vaccine studies have included children with JIA, and biological therapy was specifically studied in only five of them (Table 3). In all but one (Toplak et al. [18]) the hemagglutination inhibition test (HAI) was used to determine antibody response to vaccination, which is known for its overall poor sensitivity, thereby potentially underestimating the seroprevalence in a given population [19]. The microneutralization assay, which was used in the present study, has been shown to enhance sensitivity and specificity [14]. No correlate of protection has been defined for microneutralization, but good correlation with HAI defined protection thresholds has been reported [16]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that HAI antibody seroprotection cut-offs in children aged 6-72 months may be 1:110 to achieve 50% protection [20], thus it is possible that children with RD may need antibody titers equal to or higher than those described. There is a need to review the current practice of evaluating vaccine responses and should include more advanced techniques to evaluate immunogenicity such as microneutralization assay, which identifies functional antibodies, rather than quantitative tests only [21].

Blockade of the IL-6R has been shown to decrease lymphocyte activation and to restore B and T cell homoeostasis in patients with SLE [22]. Anti-IL-6R treatment may diminish influenza vaccine antibody responses since IL-6 induces B cell differentiation into antibody-forming cells and T cells into effectors cells [22]. However, Shinoki et al. studied JIA patients treated with tocilizumab (anti IL-6R) and demonstrated that influenza vaccination was immunogenic and safe, as was the case in our study (Table 3) [9]. Whilst in healthy subjects therapy with anti-IL-1 did not affect the antibody responses after vaccination with influenza vaccine [23], the impact of its use in children with JIA is unknown. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating influenza vaccine in children receiving IL-1R antagonist (anakinra) for JIA and was found to be safe and immunogenic. However, further studies are needed to confirm its safety in pediatric patients, as only four patients were included here.

Anti-TNF-α therapy in rheumatoid arthritis inhibits germinal center reactions, thereby leading to decrease peripheral blood memory B cell levels, potentially contributing to a poor response to vaccination [24]. Four pediatric studies (Table 3) have evaluated influenza vaccine in JIA patients receiving anti-TNF-α therapy. Antibody titers against A(H1N1), A(H3N2), and B vaccine viruses were found to be reduced in patient receiving anti-TNF-α although only four children were enrolled [18]. In another study, 30 JIA patients treated with anti-TNF-α showed significantly lower GMTs against the A/H1N1 strain compared to those treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) and healthy controls. Furthermore, sero-conversion and -protection rates were significantly lower in patients receiving anti-TNF-α [25], as was also reported by Carvalho et al. in 5 patients and only for the A/H1N1 strain [8]. In the Aikawa et al. study, no differences were observed in immunogenicity parameters between patients with or without anti-TNF-α blockers however, the seroconversion rate for the A/H1N1 strain was significantly lower in JIA patients compared to controls (83.2% vs. 95.6%, p = 0.008) [26]. In our study, no differences between the control group and patients with or without biological therapy were observed, thus biological therapy plus MTX did not alter the vaccine response. Although lack of differences between groups could be due to the small sample size, these findings are in contrast with previous results, where the use of anti-TNF-α blockers was associated with a reduced vaccine response [25, 26]. One year after vaccination seroprotection rates were similar with a slight and expectable reduction for all strains but A/H3N2, which was higher. This could be due to natural exposition to the virus, or test precision variability. Although it was evaluated in only few patients, biological treatment seems not to influence in long-term seroprotection rates after vaccination.

Like in other studies in children with RD, no SAEs were reported and vaccination using an inactivated influenza vaccine was shown to be safe with mild systemic and local reactions as most reported AEFI [26, 27]. Our patients remained clinically stable (JADAS-71:1 (0-5)) during the study period with only two patients receiving systemic corticoids at the time of vaccination. Lack of active inflammation at the time of vaccination could have influenced the safety and immunogenicity outcomes in our cohort. This is supported by the study of Toplak et al., where only 42% of the children had inactive disease at the time of vaccination and all children suffering from a flare post vaccination, had at least one criterion for active disease prior to vaccination [18]. This is important as high dose steroid therapy is known to be associated with a reduced immnunogenicity of the influenza vaccine resulting in lower antibody titers [28, 29]. We observed seroprotected patients to have lower inflammatory markers such as platelet count and ESR compared to non-seroprotected children. A low inflammatory state may result in an enhanced cellular immune response (Th1 vs Th2) thereby supporting B and T cell differentiation with subsequent improved vaccine response [30, 31]. In contrast to the studies of Dell’ Era and Toplak et al. where only 8.3% and 13% of the patients were previously vaccinated, 62.8% of children with JIA (and 72% of those receiving biological treatment) received the influenza vaccine the season prior to this study, and that has likely contributed to the overall high vaccine response shown here. This is also supported by previous results suggesting that baseline seroprotection promotes significantly higher GMT after vaccination [32]. Whilst over 60% (H1N1 68.6%, H3N2 62.9% and Flu B 68.6%) of our JIA children were seroprotected prior vaccination, only 20% of the patients described by Toplak and Aikawa et al. showed pre-vaccine seroprotection, further supporting the benefit of seasonal influenza vaccination. However, differences between participant’s age and previous exposure to the virus could alter pre-vaccination seroprotection rates. A limitation of this study is the overall low number of patients and healthy controls included, which may have limited the power to detect differences, especially when performing subgroup analysis. Although clinical, laboratory baseline parameters and GMT baseline titers were similar in the groups; there was heterogeneity in the treatment used and likely in the previous influenza exposure (artificial or natural) of the included patients. Further studies evaluating vaccine efficacy and effectiveness are necessary.

Conclusions

In this prospective study of children with JIA, the use of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine including A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B strains was shown to be safe and immunogenic. The type of immunomodulatory therapy did not alter vaccine response. This patient group would likely benefit from seasonal influenza vaccination thereby supporting the annual immunization program.

Abbreviations

- AEFI:

-

adverse events following immunization

- AESI:

-

Adverse events of special interest

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- GMR:

-

Geometric mean ratio

- GMT:

-

Geometric mean titers

- GVSI:

-

Global Vaccine Safety Initiative

- JADAS:

-

Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score

- JIA:

-

juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- SAE:

-

severe adverse events

- Tpv:

-

time post vaccination

References

Dell’ Era L, Esposito S, Corona F, Principi N. Vaccination of children and adolescents with rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) [Internet]. 2011;50(8):1358–1365. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21482543.

Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, et al. 2013 IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Vaccination of the Immunocompromised Host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:e44–100.

Heijstek MW, Ott de Bruin LM, Borrow R, van der Klis F, Koné-Paut I, Fasth A, et al. Vaccination in paediatric patients with auto-immune rheumatic diseases: A systemic literature review for the European League against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;11(2):112–22.

Heijstek MW, Ott de Bruin LM, Bijl M, Borrow R, F K-PI v d K. EULAR recommendations for vaccination in paediatric patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1704–12.

Miraglia JL, Abdala E, Hoff PM, Luiz AM, Oliveira DS, Saad CGS, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of 2009 influenza a (H1N1) inactivated monovalent non-adjuvanted vaccine in elderly and immunocompromised patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27214.

Malleson PN, Tekano JL, Scheifele DWWJ. Influenza immunization in children with chronic arthritis: a prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1993;Oct;20(10):1769–7.

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg JHX, Maldonado-Cocco J, Orozco-Alcala J, Prieur AM, Suarez-Almazor MEWP, Rheumatology. IL of A for. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–2.

Carvalho LM, De Paula FE, Silvestre RVD, Roberti LR, Arruda E, Mello WA, et al. Prospective surveillance study of acute respiratory infections, influenza-like illness and seasonal influenza vaccine in a cohort of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2013;11:10.

Shinoki T, Hara R, Kaneko U, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, Mori M, et al. Safety and response to influenza vaccine in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis receiving tocilizumab. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22(6):871–6.

Ogimi C, Tanaka R, Saitoh A, Oh-Ishi T. Immunogenicity of Influenza Vaccine in Children With Pediatric Rheumatic Diseases Receiving Immunosuppressive Agents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(3):208–11.

Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A, Pistorio A, Magni-Manzoni S, Filocamo G, et al. Development and Validation of a Composite Disease Activity Score for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61(5):658–66.

The Global Vaccine Safety Initiative (GVSI [Internet]. Available from: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/initiative/en. Accessed July 2016.

Brunner HI, Lovell DJ, Finck BKGE. Preliminary definition of disease flare in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(5):1058–64.

Perez-Romero P, Bulnes-Ramos A, Torre-Cisneros J, Gavaldá J, Aydillo TA, Moreno A, et al. Influenza vaccination during the first 6 months after solid organ transplantation is efficacious and safe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(11):1040.e11–8.

The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA). Comitte for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). Note for guidence on harmonisation of requirements for influenza vaccines. WwwEudraOrg/EmeaHtml [Internet]. 1997;19. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003945.pdf. Accessed July 2016.

Trombetta C, Perini D, Mather S, Temperton N, Montomoli E. Overview of Serological Techniques for Influenza Vaccine Evaluation: Past, Present and Future. Vaccine. 2014;2(4):707–34. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/2/4/707/

Consolaro A, Giancane G, Schiappapietra B, Davì S, Calandra S, Lanni S, et al. Clinical outcome measures in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27089922%5Cn, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4836071

Toplak N, Šubelj V, Kveder T, Čučnik S, Prosenc K, Trampuš-Bakija A, et al. Paediatric rheumatology Safety and efficacy of influenza vaccination in a prospective longitudinal study of 31 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:436–44.

Verschoor CP, Singh P, Russell ML, Bowdish DME, Brewer A, Cyr L, et al. Microneutralization assay titres correlate with protection against seasonal influenza H1N1 and H3N2 in children. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):7–13.

Black S, Nicolay U, Vesikari T, Knuf M, Del Giudice G, Della Cioppa G, et al. Hemagglutination Inhibition Antibody Titers as a Correlate of Protection for Inactivated Influenza Vaccines in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;30(12):1081–5.

Cagigi A, Cotugno N, Rinaldi S, Santilli V, Rossi P, Palma P. Downfall of the current antibody correlates of influenza vaccine response in yearly vaccinated subjects: Toward qualitative rather than quantitative assays. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2016;27(1):22–7.

Shirota Y, Yarboro C, Fischer R, Pham T, Lipsky P, Illei GG. Impact of anti-interleukin-6 receptor blockade on circulating T and B cell subsets in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(1):118–28.

Chioato A, Noseda E, Felix SD, Stevens M, Del Giudice G, Fitoussi S, et al. Influenza and meningococcal vaccinations are effective in healthy subjects treated with the interleukin-1-blocking antibody canakinumab: Results of an open-label, parallel group, randomized, single-center study. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(12):1952–7.

Kobie JJ, Zheng B, Bryk P, Barnes M, Ritchlin CT, Tabechian DA, et al. Decreased influenza-specific B cell responses in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):R209. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22177419.

Dell’Era L, Corona F, Daleno C, Scala A, Principi N, Esposito S. Immunogenicity, safety and tolerability of MF59-adjuvanted seasonal influenza vaccine in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Vaccine. 2012;20;30(5):936–40.

Aikawa NE, Campos LMA, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Saad CGS, Ribeiro AC, Bueno C, et al. Effective seroconversion and safety following the pandemic influenza vaccination (anti-H1N1) in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol [Internet]. 2013;42(1):34–40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22992045.

Woerner A, Sauvain M-J, Aebi C, Otth M, Bolt IB. Immune response to influenza vaccination in children treated with methotrexate or/and tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(12):1293–8.

Sengler C, Niewerth M, Kallinich T, Nimtz-Talaska A, Haller M, Huppertz HI, et al. Survey about tolerance of the AS03-adjuvanted H1N1 influenza vaccine in children with rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(1):137–9.

Aikawa NE, França ILA, Ribeiro AC, Sallum AME, Bonfa E, Silva CA. Short and long-term immunogenicity and safety following the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients under conventional DMARDs with or without anti-TNF therapy. Vaccine. 2015;33(5):604–9.

Campos LMA, Silva CA, Aikawa NE, Jesus AA, Moraes JCB, Miraglia J, et al. High disease activity: An independent factor for reduced immunogenicity of the pandemic influenza a vaccine in patients with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(7):1121–7.

Trzonkowski P, Myśliwska J, Szmit E, Wiȩckiewicz J, Łukaszuk K, Brydak LB, et al. Association between cytomegalovirus infection, enhanced proinflammatory response and low level of anti-hemagglutinins during the anti-influenza vaccination - An impact of immunosenescence. Vaccine. 2003;21(25–26):3826–36.

Cordero E, Aydillo TA, Perez-Ordoñez A, Torre-Cisneros J, Lara R, Segura C, et al. Deficient long-term response to pandemic vaccine results in an insufficient antibody response to seasonal influenza vaccination in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation [Internet]. 2012;93(8):847–854. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22377789

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients, siblings and their parents for participating in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the

-

Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria [PI1101537], Consejería de Economía e Innovación [CTS-2012-1909] and Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FEDER, Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases [REIPI RD06/0008/0000].

-

CLMS was supported by Sociedad Española de Reumatología Pediátrica (SERPE)

-

PRP is supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (CP11/00314) co-financed by the Programa Nicolás Monardes (RC-0005-2015) Servicio Andaluz de Salud, Junta de Andalucía.

-

CLMS and NCE are members of PRINTO, SHARE y SERPE

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CLMS, BRA, NO, PRP participated in the design of the study. CLMS, BRA, GVW performed the statistical analysis. CLMS, FSL, NCE recruited patients and included clinical data. BRA, PRP performed microneutralization assay. All authors participated in the coordination of the study and helped to draft the manuscript lead by CLMS, BRA, NO, PRP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of the local Hospital approved the study (2013PI/255). Patients (aged 1-18 years) and healthy siblings, as controls, were included consecutively after the legal guardians signed informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional information

M. S. Camacho-Lovillo and A. Bulnes-Ramos shared 1st authors.

O. Neth and P. Pérez-Romero shared last authors.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Influenza A/(H1N1)pdm, A/H3N2 and B virus antibody response in JIA patients according to type of biological therapy. (DOCX 42 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Multivariable analysis for Post-vaccine seroprotection in patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Camacho-Lovillo, M.S., Bulnes-Ramos, A., Goycochea-Valdivia, W. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of influenza vaccination in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on biological therapy using the microneutralization assay. Pediatr Rheumatol 15, 62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-017-0190-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-017-0190-0