Abstract

Background

Disease progression in the absence of therapy varies significantly in mono-HIV and HCV infected individuals. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells play an important role in restricting lentiviral replication and determining the rate of disease progression during HIV and HCV mono- and co-infection. Thus, understanding the similarities in the characteristics of CD8+ T cells in mono-HIV and HCV infection at the transcriptomic level contributes to the development of antiviral therapy. In this study, a meta-analysis of CD8+ T cell gene expression profiles derived from mono-HIV and HCV infected individuals at different stages of disease progression, was conducted to understand the common changes experienced by CD8+ T cells.

Methods

Five microarray datasets, reporting CD8+ T cell mRNA expression of the mono-HIV and HCV infected patients, were retrieved from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified via integrative meta-analysis of expression data (INMEX) program. Network analysis methods were used to assess protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks, Gene Ontology (GO) terms and pathway enrichment for DEGs. MirDIP and miRDB online prediction tools were used to predict potential microRNAs (miRNAs) targeting hub genes.

Results

First, we identified 625 and 154 DEGs in the CD8+ T cells originating from mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressor patients, respectively, compared to healthy individuals. Among them, interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) including ISG15, IFIT3, ILI44L, CXCL8, FPR1 and TLR2, were upregulated after mono-HIV and HCV infection. Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs showed that the “cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction” and “NF-kappa B” signaling pathways were upregulated after mono-HIV and HCV infection. In addition, we identified 92 and 50 DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of HIV non-progressor and HCV resolver patients, respectively, compared with corresponding chronic progressors. We observed attenuated mitosis and reduced ISG expression in HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers compared with the corresponding chronic progressors. Finally, we identified miRNA-143-3p, predicted to target both IFIT3 in HIV and STAT5A in HCV infection.

Conclusions

We identified DEGs and transcriptional patterns in mono-HIV and HCV infected individuals at different stages of disease progression and identified miRNA-143-3p with potential to intervene disease progression, which provides a new strategy for developing targeted therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are caused by small, highly mutable, rapidly replicating RNA viruses with the ability to establish long-term chronic pathogenic infection in human hosts. Disease progression in the absence of therapy varies significantly in mono-HIV and HCV-infected individuals. HIV-infected patients experience progressive CD4+ T cell loss and develop AIDS [1]. However, a small proportion of HIV-infected patients remain clinically and/or immunologically stable for years, including long-term non-progressors (LTNPs), who maintain normal CD4+ T cell counts for prolonged periods (> 10 years) and elite controllers (ECs), who have undetectable viremia (< 50 copies/ml) [2,3,4]. HCV is a major cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular cancer worldwide. However, a minority of people (< 30%) who resolve acute hepatitis spontaneously (HCV resolvers) [5], are characterized by undetectable HCV RNA in the presence of HCV antibodies [6]. Since HIV infection is often complicated by co-infection with HCV [7], understanding the common characteristics of the immune response in mono-HIV and HCV infection may contribute to the development of more effective therapies, aimed specifically at mono- and co-infected individuals.

Virus-specific CD8+ T cells play an important role in restricting lentiviral replication, and help determining the rate of disease progression in both human hosts and non-human primate models [8, 9]. During HIV infection, a close association was observed between CD8+ T cells targeting the HIV-Gag protein and viral control [10,11,12,13]. Elite controllers was partially linked to higher levels of cytolytic granules within HIV-specific CD8+ T cells [14]. Additionally, CD8+ T cells isolated from ECs exhibited higher polyfunctional capability in response to HIV specific antigens [15,16,17,18]. In acute HCV infection, CD8+ T cells have a crucial role in determining spontaneous resolution versus viral persistence. This role is clearly supported by chimpanzee studies showing that the depletion of CD8+ T cells hampers HCV clearance and clinical recovery [19, 20]. Cooper et al. evidenced that in contrast with chronic progressors, CD8+ T cells from resolvers generated more potent acute cytotoxic responses, which correlated more strongly with protection against HCV infection than the presence of anti-HCV antibodies [5]. Badr et al. demonstrated that HCV-specific polyfunctional CD8+ T cells in resolver patients exhibited increased proliferation and cytokine production in contrast to the cells in chronic infected individuals [21]. Comparing the transcriptional changes of the CD8+ T cells of mono-HIV and HCV infected individuals contributes to our understanding of the pathogenesis and immunogenicity of these viruses. Gene expression profiling has provided a unique opportunity for evaluating virus-host interactions at the transcriptional level. Several independent studies have provided useful insights into mono-HIV and HCV infection [22,23,24,25]. However, the transcriptomic profiles of CD8+ T cells in mono-HIV and HCV infection needs further elucidation, in order to determine any important differences or similarities.

In the current study, we used a meta-analysis approach, which aims to incorporate high-throughput data from multiple independent studies, to compare global expression profiles of CD8+ T cells in mono-HIV and HCV infection. Our study identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within the CD8+ T cells of a number of patient groups, including mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors, HIV non-progressors, HCV resolvers and healthy controls. We subsequently performed a bioinformatic analysis of the identified DEGs to provide new insights into mono-HIV and HCV pathogenesis and inform the development of new therapeutic strategies for delaying disease progression.

Materials and methods

Microarray data collection

Expression profiling studies were identified through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) [26]. Using the search terms “HIV AND CD8+ T cells” and “HCV AND CD8+ T cells”, nine microarray gene expression datasets, reporting the expression data for LTNPs or ECs, resolvers, chronic progressors and healthy donors were retrieved from public repositories. To reduce the heterogeneity and increase the consistency between different datasets, we selected five microarray data from Human Genome U133A or Human Genome U133 plus 2 Array (Affymetrix Company). The characteristics of the five datasets are listed in Table 1. The following information was extracted from each of the studies that were selected: GEO accession; platform; sample source and sample size. Five datasets were conducted in Affymetrix HG U133 Gene Chips and all involved CD8+ T cells were from PBMC. For the GSE6740 and GSE49954 datasets, chronic progressors of mono-HIV and HCV infection were labelled the “case group” while healthy donors were considered as the “control group”.

For the GSE24081, GSE6740, GSE93711 and GSE93712 datasets, the HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers were labelled as the “case group” while chronic progressors were considered as the “control group”. The HIV chronic progressors analyzed were infected at least 1 years with evident CD4+ T cell decline to < 500 cells/ul and a viral load of > 10,000 copies/ml. The HIV non-progressors analyzed were infected at least 3 years with no evidence of CD4 + T-cell decline and a viral load of < 500 copies/ml. The HCV chronic progressors and resolvers analyzed were during the acute phase of infection (≤ 36 weeks).

Analysis of differentially expression genes (DEGs)

To find DEGs within the CD8+ T cells derived from mono- HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors, we ran “affy” [27] and “limma” [28] R packages (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/affy.html) to assess GSE6740 and GSE49954 RAW datasets. After background correction, quantile normalization, and summarization using RMA (Robust Multichip Average) analysis by “affy” package, expression data were log2 transformed for further analysis. Empirical Bayesian model in limma was used to identify the DEGs. Significantly differentially expressed genes were defined as those with a P < 0.05 and ≥ 1.5-fold change cutoff.

To find DEGs within the CD8+ T cells of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, compared with corresponding chronic progressors, the data collected from each eligible microarray study were imported into the Integrative Meta-analysis of Expression Data (INMEX) program (http://www.inmex.ca), prior to performing the meta-analysis [29]. The GSE24081 and GSE6740 or GSE93711 and GSE93712 data were annotated after converting the gene and probe IDs to the corresponding Entrez IDs. The intensity values for each probe set were log2 transformed then uploaded, processed, and annotated for data integrity. Then, batch effect correction option (ComBat) was used to reduce potential batch effect (Additional file 1) [30]. After a data integrity check, we carried out a combined P values method, which is routinely used in the meta-analysis of microarray data [29, 31]. However, in microarray meta-analysis, a larger sample size may not warrant a larger weight, as the quality of each study can be variable. Thus, we choose Fisher’s combined P values method, which offers the advantage of being a “weight-free” method. Fisher’ method could combine P-values from independent tests of significance [31]. We consider genes with a combined P value less than 0.10 cutoff as differentially expressed genes.

Identification of DEG protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks

DEG PPI networks were analyzed using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, V10.5; http://string-db.org/) to predict gene-protein functional associations and protein–protein interactions. Subsequently, Cytoscape software (V3.5.1; http://cytoscape.org/) was applied to visualize and analyze biological networks and node degrees, after downloading analytic results of the STRING database with a confidence score > 0.4 [32].

Gene Ontology terms and pathway enrichment

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery bioinformatics resources (DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) [33]. GO terms and KEGG maps of biological functions associated with a P < 0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched.

Subsequently, we applied the microRNA Data Integration Portal (mirDIP) (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP) [34] and the miRDB (http://mirdb.org/) [35] online prediction tools to predict potential microRNAs targeting hub genes in mono-HIV and HCV infected individuals.

Results

DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

Firstly, we identified the DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors, compared to healthy donors. According to the results of our analysis, 625 genes were identified to be differentially expressed between HIV chronic progressors and healthy donors. Of the 625 DEGs, 136 genes were upregulated and 489 genes were downregulated (Additional file 2).

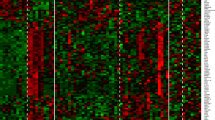

154 genes, identified in the CD8+ T cells from HCV-infected patients, were differentially expressed between chronic progressors and healthy donors across microarray datasets. Of the 154 DEGs, 56 genes were upregulated and 98 genes were downregulated (Additional file 3). As demonstrated in the heatmap, DEGs can clearly segregate HIV (Fig. 1a) and HCV chronic progressors (Fig. 1b) from healthy donors.

DEG heatmaps. a Heatmap showing DEGs from HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. Each row represents a gene and each line represents a sample. Red represents higher expression and green represents lower expression. b Heatmap showing DEGs from HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. Each row represents a gene and each line represents a sample. Red represents higher expression and green represents lower expression

PPI network analysis of DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

Next, we performed PPI network analysis of DEGs in the CD8+ T cell of mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors, to identify the hub nodes. We identified 542 nodes from the PPI network of the CD8+ T cell-specific DEGs of HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors, and ranked the top 100 nodes by degree (Fig. 2a). We found that most of these 100 nodes were upregulated interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) such as STAT1 (degree = 86), IRF7 (degree = 55), ISG15 (degree = 51), MX1 (degree = 45), GBP1 (degree = 44), OAS1 (degree = 41), IFIT3 (degree = 38), IFIT1 (degree = 37) and IFI44L (degree = 35) [22, 36,37,38].

DEG PPI networks and Venn diagrams. a PPI network showing DEGs from HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. The top 100 nodes, ranked by degree, are shown. b PPI network showing DEGs from HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. In a and b red = greater degree, yellow = lesser degree. c Venn diagram of co-DEGs

We identified 92 nodes from the PPI network of the CD8+ T cell-specific DEGs of HCV chronic progressors compared to healthy donors (Fig. 2b). The following eight HCV DEG hub nodes ranked most highly, including IL1-β (degree = 31), CXCL8 (also known as IL-8 and degree = 31), TLR2 (degree = 28), IL1RN (degree = 21), TREM1 (degree = 19), CXCL2 (degree = 18), PTGS2 (degree = 17) and FPR1 (degree = 17). Of these, CXCL8, TLR2 and FPR1 are also upregulated ISGs [39].

We further investigated whether some of the CD8+ T cell DEGs were shared in mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. The Venn diagram showed that 17 DEGs were significantly altered (Fig. 2c and Table 2). GO analysis was carried out for the functional investigation of 17 co-DEGs, revealing that the “cellular defense response” term was significantly enriched (P = 0.043).

Functional GO terms and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

GO and KEGG pathway analysis were carried out to investigate the common biological processes and pathways associated with the CD8+ T cells DEGs after mono-HIV and HCV infection. Following GO analysis, the “innate immune response”, “immune response”, “inflammatory response”, “positive regulation of NF-kappa B transcription factor activity” and “response to lipopolysaccharide” were significantly enriched for DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of both HIV (Fig. 3a) and HCV chronic progressors (Fig. 3b), compared with healthy donors.

GO and KEGG analysis of DEGs. a Gene Ontology (GO) classification of DEGs from HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. b GO classification of DEGs from HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. c KEGG pathways of upregulated DEGs from HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors. d KEGG pathways of upregulated DEGs from HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

In the pathway analysis, we identified significantly upregulated pathways enriched for DEGs in the CD8+ T cells from mono-HIV (Fig. 3c) and HCV chronic progressors (Fig. 3d), compared with healthy donors. The “NF-kappa B signaling pathway” and “cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction signaling pathway” were significantly upregulated in CD8+ T cells after mono-HIV and HCV infection. In addition, “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway” (P = 0.078 in HIV infection, P = 0.011 in HCV infection) and “TNF signaling pathway” (P = 0.08 in HIV infection, P = 0.079 in HCV infection) also have upregulated tendency after mono-HIV and HCV infection.

DEGs from HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers compared with corresponding chronic progressors and associated pathway enrichment analysis

Next, in order to understand the changes experienced by CD8+ T cells at different stages of disease progression, we compared the transcriptional profiles of CD8+ T cell from HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, versus chronic progressors. At first, we identified 92 DEGs by comparing the transcriptional profiles of CD8+ T cell from HIV non-progressors versus chronic progressors. Of the 92 DEGs, 47 genes were upregulated and 45 genes were downregulated (Additional file 4). Then, we identified 50 DEGs by comparing the transcriptional profiles of CD8+ T cell from HCV resolvers versus chronic progressors. Among the 50 DEGs, 13 genes were upregulated and 37 genes were downregulated (Additional file 5).

KEGG pathway analysis was subsequently carried out for the functional investigation of DEGs in the CD8+ T cell of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, versus the corresponding chronic progressors. Pathway analysis identified that 7 pathways were commonly shared in HIV non-progressors (Fig. 4a) and HCV resolves (Fig. 4b), compared to chronic progressors. This included the “TGF-beta signaling”, “cell cycle”, “herpes simplex infection”, “hepatitis B”, “hepatitis C”, “measles” and “influenza A” pathways.

KEGG pathways of DEGs. a KEGG pathways of DEGs from HIV non-progressors compared with chronic progressors. b KEGG pathways of DEGs from HCV resolvers compared with chronic progressors. c Number of DEGs identified in the CD8+ T cells of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers compared with chronic progressors, involved in the mitotic cell cycle and cell apoptosis processes. Red = upregulated DEGs, green = downregulated DEGs

Cell cycle is associated with CD8+ T cell function during viral infection. We then performed the GO cell cycle analysis with the upregulated and downregulated DEGs to investigate the alterations of cell cycle. In HIV non-progressors versus chronic progressors, 5 downregulated genes and 2 upregulated genes were shown to be involved in the mitotic cell cycle, with all 7 genes being essential for mitosis. Upregulated genes included PLK2 and TUBGCP3 and downregulated genes comprised HSPA1A, CCNA2, PSME2, TOP2A and NDC80. The larger number of downregulated genes compared to upregulated genes may be indicative of mitosis attenuation. In HCV resolvers versus chronic progressors, one upregulated gene, RBL2, was identified. RBL2 acts as a negatively regulated transcription factor of the mitotic cell cycle, and its expression may also be responsible for dampening cell division. In addition, we found two downregulated genes, STAT5A and MTCH1, associated with the cell apoptosis. However, no upregulated genes associated with cell apoptosis were found in the CD8+ T cells of HCV resolvers versus chronic progressors (Fig. 4c). The above results suggest that in HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, disease progression may be prevented by increased CD8+ T cell survival, mediated by a combination of an attenuated mitotic cell cycle and reduced apoptosis.

PPI network analysis of CD8+ T cell DEGs of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, compared with chronic progressors, and the identification of predicted miRNAs

Finally, we performed PPI network analysis of DEGs in the CD8+ T cells of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, versus the corresponding chronic progressors, with the aim of identifying hub nodes. Given the multi-targeting property of miRNA, we expected to identify miRNAs targeting both HIV and HCV hub genes to intervene in HIV and HCV mono- and co-infection.

In HIV non-progressors versus chronic progressors, we identified 10 hub nodes, including GBP1 (degree = 19), MX1 (degree = 17), IRF9 (degree = 17), EIF2AK2 (degree = 17), IFIT3 (degree = 16), OAS1 (degree = 16), IFI44L (degree = 15), IFIT1 (degree = 15), IFI6 (degree = 15) and IFITM1 (degree = 15) (Fig. 5a). Most of the listed hub nodes were downregulated ISGs. In HCV resolvers versus chronic progressors, we identified three hub nodes, including EP300 (degree = 5), STAT5A (degree = 3) and PPP2CA (degree = 3), all of which were downregulated (Fig. 5b).

In order to interfere with disease progression by identifying key miRNAs with the capacity to target both HIV and HCV hub genes, we performed prediction analysis using mirDIP and miRDB bioinformatic tools. We identified 9 candidate miRNAs targeting IFIT3 in the context of HIV infection and 16 candidate miRNAs targeting STAT5A in HCV infection (Additional file 6). We found the miR-143-3p could target both IFIT3 and STAT5A. Clapé et al. evidenced that ERK5 is a miR-143 target gene [40], whilst, Wilhelmsen et al. demonstrated that this gene plays a proinflammatory role in primary human endothelial cells and monocytes [41]. We thus deduced that miRNA-143-3p may exert its anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing ERK5. Finally, through cell transfection and PCR technology, we found that overexpression of miRNA-143-3p can suppress ERK5 expression in primary CD8+ T cells by paired t-test, suggesting the fine tune effect of miRNA-143-3p on ERK5 (Additional file 7).

Discussion

Identification of the most relevant genes and pathways involved in mono-HIV and HCV infection is important for broadening our understanding of the molecular and cellular processes determining disease progression. In our study, we first identified CD8+ T cell-associated DEGs in mono-HIV and HCV chronic progressors, compared with healthy donors, and found that ISGs were commonly upregulated. Furthermore, we found that the “cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction” and “NF-kappa B” signaling pathways were also upregulated after mono-HIV and HCV infection. In addition, we observed attenuated mitosis and reduced ISG expression in the CD8+ T cells of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, compared with chronic progressors. Finally, we identified and predicted miRNAs that may interfere with HIV and HCV mono- and co-infection.

Firstly, the comparison of CD8+ T cell transcriptional profiles after mono-HIV and HCV infection demonstrated that certain ISGs, including STAT1, ISG15, IFIT1, IFIT3 and IFI44L, were significantly upregulated in HIV chronic progressors. Meanwhile, CXCL8, TLR2 and FPR1 were significantly upregulated in HCV chronic progressors. Several studies have highlighted the role of ISGs in the progression of mono-HIV and HCV infection [22, 42, 43]. Type-I interferons (IFNs) are of critical importance in the control of viral disease due to their potent antiviral effects, mediated by interferon-induced proteins [44, 45]. However, it is also well established that type-I IFNs are especially effective at very low concentrations and their expression is required locally [46, 47]. Emerging lines of evidence reveal that high and sustained levels of type-I IFN expression are associated with hyper-immune activation and disease progression in persistent infection [47,48,49,50,51]. The upregulated “cytokine–cytokine receptor” and “NF-kappa B” signaling pathways also reflects a high level of immune activation [52,53,54]. The dynamics of type-I IFN expression distinguishes between simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of natural hosts, that do not develop AIDS, from pathogenic SIV infection [55,56,57,58]. Natural hosts can rapidly silence their type-I IFN response after acute SIV infection, whereas, disease-susceptible macaque species maintain type-I IFN signaling indefinitely, thus triggering the hyper-activation of the immune system and contributing to an environment that favors progression to AIDS [56,57,58,59,60]. Persistent hyper-immune activation also results in immune exhaustion [61,62,63], including the loss of CD8+ T cell function. Several studies have demonstrated that the hyper-activation of virus-specific T cells, caused by the strong and sustained production of type-I IFNs, may hamper viral clearance [50, 64]. In addition, an inefficient T cell response that fails to clear HCV infection creates a chronic inflammatory process, the end result of which are hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC [65]. Collectively, our results indicate that the increased expression of ISGs, which leads to elevated levels of immune activation, is a key factor affecting disease progression.

Secondly, the comparison of CD8+ T cell transcriptional profiles of HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, versus chronic progressors, revealed several common pathways associated with both HIV and HCV, including the “herpes simplex infection” “measles”, “influenza A”, “hepatitis B”, “hepatitis C”, “TGF-beta” and “cell cycle” pathways. Maintaining normal cell cycle function is essential for the antiviral activity of CD8+ T cells. However, CD8+ T cell turnover is increased in HIV infected individuals, which reflects a hyper-activated immune status that contributes to the exhaustion and depletion of this important cell subset [66,67,68,69]. By comparing HIV non-progressors with chronic progressors, we found that all the DEGs associated with the mitotic cell cycle were essential for mitosis, and the majority of these DEGs were downregulated. The relatively high numbers of downregulated genes associated with the mitotic cell cycle may suggest CD8+ T cell mitotic attenuation in HIV non-processors compared with chronic progressors. By comparing HCV resolvers with chronic progressors, we found one upregulated gene, RBL2, a negatively regulated transcription factor involved in the mitotic cell cycle, which may also imply an attenuated CD8+ T cell mitosis. Additionally, we identified two downregulated cell apoptosis-associated genes, STAT5A and MTCH1, while no apoptotic genes were upregulated, which may be indicative of a reduction in the apoptosis of the CD8+ T cells within HCV resolvers, compared with chronic progressors. The relatively low turnover of CD8+ T cells in HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers may be one reason for their ability to maintain the non-progression of disease.

Since miRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs involved in the regulation of gene expression via mRNA degradation or translational repression [70,71,72,73], we expected to find miRNAs capable of interfering with HIV and HCV mono- and co-infection. Moreover, as no co-DEGs were found in HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, compared with chronic progressors, we used the PPI network to identify DEG hub nodes. The PPI analysis of HIV infection revealed that the identified hub genes were mostly downregulated ISGs, which directly opposed the above-mentioned result expected for the comparison of chronic progressors with healthy donors. Our PPI analysis of HCV infection showed that the hub gene STAT5A, responsible for type-I IFN signal transduction to the promoters of ISGs, was downregulated [74, 75]. Given the multi-targeting property of miRNAs [76,77,78,79], we finally identified the miR-143-3p, with the ability to target both IFIT3 and STAT5A, in HIV and HCV infection, respectively. Clapé et al. evidenced that ERK5 is a miR-143 target gene [40], whilst, Wilhelmsen and et al. demonstrated that this gene plays a proinflammatory role in primary human endothelial cells and monocytes [41]. We thus deduced that miRNA-143-3p may exert its anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing ERK5. Such miRNA-143-3p-mediated suppression of inflammatory cytokine overproduction may be exploited as a therapeutic strategy in the context of HIV/HCV mono- and co-infection.

Conclusion

In summary, our analysis of microarray studies shows that the upregulation of ISGs and the NF-kappa B signaling pathway are collectively indicative of persistent immune activation in the context of mono-HIV and HCV infection. The decreased turnover of CD8+ T cells, as seen in HIV non-progressors and HCV resolvers, may reduce CD8+ T cell exhaustion and limit disease progression.

Availability of data and materials

GSE49954, GSE24081, GSE6740, GSE93711 and GSE93712 datasets were downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). R packages of “affy”, and “limma” (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/affy.html), provided by a bioconductor project, were applied to assess GSE6740 and GSE49954 RAW datasets. INMEX program (http://www.inmex.ca) were applied to assess GSE24081, GSE6740, GSE93711 and GSE93712.

Abbreviations

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- INMEX:

-

Integrative meta-analysis of expression data

- PPI:

-

Protein–protein interaction

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- miRNAs:

-

microRNAs

- ISGs:

-

Interferon-stimulated genes

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- LTNPs:

-

Long-term non-progressors

- ECs:

-

Elite controllers

- STRING:

-

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- IFNs:

-

Interferons

- HD:

-

Healthy donor

- CP:

-

Chronic progressor

- NP:

-

Non-progressor

- RP:

-

Resolver patient

- CXCL8:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8

- CXCL2:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2

- STAT1:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- IRF7:

-

Interferon regulatory factor 7

- ISG15:

-

Interferon-stimulated gene 15

- MX1:

-

MX dynamin like GTPase 1

- GBP1:

-

Guanylate binding protein 1

- OAS1:

-

2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1

- IFIT3:

-

Interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3

- IFIT1:

-

Interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1

- IFI44L:

-

Interferon induced protein 44 like

- IL1-β:

-

Interleukin 1 beta

- TLR2:

-

Toll like receptor 2

- IL1RN:

-

Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

- TREM1:

-

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1

- PTGS2:

-

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2

- FPR1:

-

Formyl peptide receptor 1

- PLK2:

-

Polo like kinase 2

- TUBGCP3:

-

Tubulin gamma complex associated protein 3

- HSPA1A:

-

Heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 1A

- CCNA2:

-

Cyclin A2

- PSME2:

-

Proteasome activator subunit 2

- TOP2A:

-

DNA topoisomerase II alpha

- NDC80:

-

NDC80 kinetochore complex component

- RBL2:

-

RB transcriptional corepressor like 2

- STAT5A:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A

- MTCH1:

-

Mitochondrial carrier 1

- IRF9:

-

Interferon regulatory factor 9

- EIF2AK2:

-

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2

- IFI6:

-

Interferon alpha inducible protein 6

- IFITM1:

-

Interferon induced transmembrane protein 1

- EP300:

-

E1A binding protein p300

- PPP2CA:

-

Protein phosphatase 2 catalytic subunit alpha

References

Carrington M, Walker BD. Immunogenetics of spontaneous control of HIV. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:131–45.

Deeks SG, Walker BD. Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity. 2007;27(3):406–16.

Pantaleo G, Fauci AS. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of HIV infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:487–512.

Dyer WB, et al. Mechanisms of HIV non-progression; robust and sustained CD4 + T-cell proliferative responses to p24 antigen correlate with control of viraemia and lack of disease progression after long-term transfusion-acquired HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology. 2008;5:112.

Cooper S, et al. Analysis of a successful immune response against hepatitis C virus. Immunity. 1999;10(4):439–49.

Semmo N, et al. Preferential loss of IL-2-secreting CD4+ T helper cells in chronic HCV infection. Hepatology. 2005;41(5):1019–28.

Sulkowski MS. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection. J Hepatol. 2008;48(2):353–67.

Lieberman J, et al. Dressed to kill? A review of why antiviral CD8 T lymphocytes fail to prevent progressive immunodeficiency in HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2001;98(6):1667–77.

McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones SL. Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature. 2001;410(6831):980–7.

Edwards BH, et al. Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J Virol. 2002;76(5):2298–305.

Goonetilleke N, et al. The first T cell response to transmitted/founder virus contributes to the control of acute viremia in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206(6):1253–72.

Berger CT, et al. High-functional-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to HLA-B-restricted Gag-derived epitopes associated with relative HIV control. J Virol. 2011;85(18):9334–45.

Ferrando-Martinez S, et al. Differential Gag-specific polyfunctional T cell maturation patterns in HIV-1 elite controllers. J Virol. 2012;86(7):3667–74.

Blankson JN, Siliciano RF. Elite suppression of HIV-1 replication. Immunity. 2008;29(6):845–7.

Betts MR, et al. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006;107(12):4781–9.

Ferre AL, et al. Mucosal immune responses to HIV-1 in elite controllers: a potential correlate of immune control. Blood. 2009;113(17):3978–89.

Almeida JR, et al. Superior control of HIV-1 replication by CD8+ T cells is reflected by their avidity, polyfunctionality, and clonal turnover. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2473–85.

Walker BD, Yu XG. Unravelling the mechanisms of durable control of HIV-1. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(7):487–98.

Shoukry NH, et al. Memory CD8 + T cells are required for protection from persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med. 2003;197(12):1645–55.

Grakoui A, et al. HCV persistence and immune evasion in the absence of memory T cell help. Science. 2003;302(5645):659–62.

Badr G, et al. Early interferon therapy for hepatitis C virus infection rescues polyfunctional, long-lived CD8+ memory T cells. J Virol. 2008;82(20):10017–31.

Hyrcza MD, et al. Distinct transcriptional profiles in ex vivo CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are established early in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and are characterized by a chronic interferon response as well as extensive transcriptional changes in CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3477–86.

Xu X, et al. IFN-stimulated gene LY6E in monocytes regulates the CD14/TLR4 pathway but inadequately restrains the hyperactivation of monocytes during chronic HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2014;193(8):4125–36.

Quigley M, et al. Transcriptional analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells shows that PD-1 inhibits T cell function by upregulating BATF. Nat Med. 2010;16(10):1147–51.

Zhao BB, et al. T lymphocytes from chronic HCV-infected patients are primed for activation-induced apoptosis and express unique pro-apoptotic gene signature. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77008.

Barrett T, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets–10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D1005–10.

Gautier L, et al. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):307–15.

Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47.

Xia J, et al. INMEX–a web-based tool for integrative meta-analysis of expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W63–70.

Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):118–27.

Rhodes DR, et al. Meta-analysis of microarrays: interstudy validation of gene expression profiles reveals pathway dysregulation in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(15):4427–33.

Szklarczyk D, et al. STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–52.

da Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57.

Pio G, et al. Integrating microRNA target predictions for the discovery of gene regulatory networks: a semi-supervised ensemble learning approach. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S4.

Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D146–52.

Brassard DL, et al. Regulation of gene expression by pegylated IFN-alpha2b and IFN-alpha2b in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24(8):455–69.

Wacher C, et al. Coordinated regulation and widespread cellular expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) ISG-49, ISG-54, and ISG-56 in the central nervous system after infection with distinct viruses. J Virol. 2007;81(2):860–71.

Zhao Y, et al. Elevated interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (IFIT3) is a poor prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(6):1061–8.

Ji X, et al. Interferon alfa regulated gene expression in patients initiating interferon treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;37(3):610–21.

Clape C, et al. miR-143 interferes with ERK5 signaling, and abrogates prostate cancer progression in mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10):e7542.

Wilhelmsen K, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 promotes acute cellular and systemic inflammation. Sci Signal. 2015;8(391):ra86.

Rotger M, et al. Comparative transcriptomics of extreme phenotypes of human HIV-1 infection and SIV infection in sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2391–400.

Heim MH, Thimme R. Innate and adaptive immune responses in HCV infections. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S14–25.

Stark GR, et al. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–64.

Gutterman JU. Cytokine therapeutics: lessons from interferon alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(4):1198–205.

Trinchieri G. Type I interferon: friend or foe? J Exp Med. 2010;207(10):2053–63.

Murira A, Lamarre A. Type-I interferon responses: from friend to foe in the battle against chronic viral infection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:609.

Herbeuval JP, Shearer GM. HIV-1 immunopathogenesis: how good interferon turns bad. Clin Immunol. 2007;123(2):121–8.

Cheng L, et al. Type I interferons suppress viral replication but contribute to T cell depletion and dysfunction during chronic HIV-1 infection. JCI Insight. 2017;2(12):e94366.

Wilson EB, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science. 2013;340(6129):202–7.

Lukhele S, Boukhaled GM, Brooks DG. Type I interferon signaling, regulation and gene stimulation in chronic virus infection. Semin Immunol. 2019;43:101277.

Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733.

Gerondakis S, Siebenlist U. Roles of the NF-kappaB pathway in lymphocyte development and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(5):a000182.

Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB in immunobiology. Cell Res. 2011;21(2):223–44.

Brenchley JM, Silvestri G, Douek DC. Nonprogressive and progressive primate immunodeficiency lentivirus infections. Immunity. 2010;32(6):737–42.

Chahroudi A, et al. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335(6073):1188–93.

Jacquelin B, et al. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of African green monkeys induces a strong but rapidly controlled type I IFN response. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(12):3544–55.

Harris LD, et al. Downregulation of robust acute type I interferon responses distinguishes nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of natural hosts from pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2010;84(15):7886–91.

Bosinger SE, Utay NS. Type I interferon: understanding its role in HIV pathogenesis and therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):41–53.

Bosinger SE, Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Generalized immune activation and innate immune responses in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6(5):411–8.

Nikolich-Zugich J. Ageing and life-long maintenance of T-cell subsets in the face of latent persistent infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(7):512–22.

Cicin-Sain L, Arens R. Exhaustion and inflation at antipodes of T cell responses to chronic virus infection. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(6):498–509.

Appay V, Rowland-Jones SL. Premature ageing of the immune system: the cause of AIDS? Trends Immunol. 2002;23(12):580–5.

Teijaro JR, et al. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science. 2013;340(6129):207–11.

Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:23–61.

Grossman Z, et al. CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV infection: are we closer to understanding the cause? Nat Med. 2002;8(4):319–23.

Sieg SF, Bazdar DA, Lederman MM. S-phase entry leads to cell death in circulating T cells from HIV-infected persons. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(6):1382–7.

Douek DC, et al. Evidence for increased T cell turnover and decreased thymic output in HIV infection. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6663–8.

Mohri H, et al. Increased turnover of T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection and its reduction by antiretroviral therapy. J Exp Med. 2001;194(9):1277–87.

Giraldez AJ, et al. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006;312(5770):75–9.

Lim LP, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433(7027):769–73.

Wu L, Fan J, Belasco JG. MicroRNAs direct rapid deadenylation of mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(11):4034–9.

Guo H, et al. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466(7308):835–40.

Brierley MM, Fish EN. Stats: multifaceted regulators of transcription. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25(12):733–44.

Darnell JE Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264(5164):1415–21.

Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20.

Engels BM, Hutvagner G. Principles and effects of microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Oncogene. 2006;25(46):6163–9.

Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D109–11.

Miranda KC, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126(6):1203–17.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Mega-Projects of National Science Research for the 13th Five-Year Plan (2017ZX10201101), Mega-Projects of National Science Research for the 12th Five-Year Plan (2015ZX10004801-002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS, ZNZ and SYL wrote and edited the manuscript. ZNZ, SYL collected and analyzed the data. HS supervised the project. YJJ participated in the data review and analysis. YJF and SYL did the in vitro experiment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants signed informed consents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

The PCAs of the matrix before and after Combat normalization

Additional file 2.

CD8+ T cell DEGs from HIV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

Additional file 3.

CD8+ T cell DEGs from HCV chronic progressors compared with healthy donors

Additional file 4.

CD8+ T cell DEGs from HIV non-progressors compared with chronic progressors

Additional file 5.

CD8+ T cell DEGs from HCV resolvers compared with chronic progressors

Additional file 6.

IFIT3- and STAT5A-targeting miRNAs

Additional file 7.

The experiment of the effect of miRNA-143-3p on suppressing ERK5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, SY., Zhang, ZN., Jiang, Y. et al. Transcriptional insights into the CD8+ T cell response in mono-HIV and HCV infection. J Transl Med 18, 96 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02252-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02252-9