Abstract

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is characterized by an inflammatory process in which T cell plays a key role. However, the profile of immune microenvironment in AMI is still uncertain. High-throughput sequencing of T cell receptor (TCR) provides deep insight into monitoring the immune microenvironment.

Methods

30 patients with AMI were enrolled and 30 healthy individuals were recruited as controls. Flow cytometer were used to analyze the distribution of αβ T cells and their CD69 expression from peripheral leukomonocytes. TCRβ repertoire library was amplified by two-round multiplex PCR and detected by next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Results

The percentage of αβ T cells in AMI patients were significantly restricted than those in healthy controls, while the highly activated αβ T cells along with distinguishing usage of variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) gene segments were also found in AMI patients. In addition, AMI induced a significantly restricted CDR3 amino acid (AA) diversity and remarkably reconstituted TCR immune repertoires. Finally, we identified several AMI-associated tendency of CDR3 AAs expression after AMI.

Conclusions

Our work suggests that the aberrant αβ T cells distribution and activation may associated with the pathogenesis of AMI and demonstrates a reconstitution of TCRβ immune repertoire after AMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), considered a lipid-related chronic inflammatory disease, often occurs on the basis of coronary atherosclerosis [1]. In general, AMI induces considerable remodelling of the myocardial tissue which leads to abnormal contractile function and heart failure, both constituting the prevailing cause for morbidity and mortality worldwide [2]. There is a global increase in the incidence of AMI in both male and female. It is estimated that AMI is responsible for over 8 million deaths each year, accounting for 5% of the global burden of disease [3].

Currently, it is widely accepted that T cells are the main immune competent cells meditated development of atherosclerotic plaques and local thrombosis [4]. It is believed that AMI is associated with T cell-associated cytokine imbalance that may act as predictors for ischemic heart disease outcomes [5, 6]. The myocardium is subject to myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury induced by re-establishment of blood flow though the majority of AMI patients is received prompt reperfusion. Emerging studies indicate that critical role of T cell in the pathogenesis of AMI injury and post myocardial infarction healing [7]. The balance of T cell-meditated immunity by the host is a major determinant of patient outcome [8], and overactive T cells, continually, lead to the progression of inflammatory response, resulting in organ dysfunction. Therefore, the potential immunosuppressive approaches may be used for the treatment of patients affected by AMI [8, 9]. Interestingly, the decrease of T lymphocyte count occurs in the circulatory system after AMI [10, 11]. The intrinsic mechanism between T cell response and AMI injury is still to need further exploration.

T cells can be divided into two major subsets characterized by the surface expression of a TCR α and β chain (αβ T cell) or γ and δ chain (γδ T cell). A majority of T cells in peripheral blood expresses is αβ T cells, while only 5–10% lymphocytes in peripheral blood are γδ T cells. T cells bear unique TCRs generated by random somatic recombination of V/(D)/J gene segments. T cell priming requires TCR ligation, by the cognate major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to recognize antigens [12, 13]. It is considered that αβ T cells can sense external environmental trigger (viral or bacterium infection) and an endogenous stimulus (homeostasis) by TCR to mediate immunosurveillance and immunoregulation, and TCR will be reconstituted in response to stimuli (infection and disease) [14,15,16]. Nevertheless, the association of TCR repertoires in AMI has not been clarified as yet.

In the basis of recent literature and finding, we hypothesized that αβ T cells exert a critical function in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of AMI, and an essential evolution of TCR repertoires may be found due to AMI-induced aberrant inflammatory microenvironment. In this study, we detected the count and activity of αβ T in peripheral blood, and NGS was used to monitor the expression pattern and clonality of TCR repertoire of αβ T cells in AMI patients. The manipulation of the heart-specific TCR immune repertoires can improve our basic understanding of T cell immunology and help to identify optimal TCRs for immunotherapy.

Methods

Participants

A total of 30 patients who diagnosed with AMI admitted to the Department of Cardiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University were enrolled. The criteria for diagnosis of AMI patients were based on the third Universal Definition of Myocardial infarction: (1) Acute ischemic chest pain within 24 h; (2) Electrocardiogram change of acute myocardial infarction (pathological Q wave, ST-segment elevation or depression) and (3) Rise of cardiac biomarkers cTnI level [17]. The diagnosis was confirmed by coronary angiogram at the admission and all of AMI patients were received reperfusion by primary percutaneous intervention (PCI) concomitantly. Additionally, 30 healthy individuals without clinical sign of myocardial ischaemia were included as controls. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Lymphocytes isolation and flow cytometry analysis

Peripheral blood samples of patients with AMI was obtained within 24 h of the onset of symptoms, the blood of patients with controls were obtained immediately after hospital admission. The blood cell count was performed using Sysmex XN (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) in the clinical laboratory of our hospital. Lymphocytes were isolated by using Ficoll (Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China) density gradient centrifugation according to instruction. Subsequently, the isolated cells were washed twice with PBS for further experiments. To detect the αβ T cells, isolated lymphocytes were incubated with fluorescently conjugated antibodies directed against mouse CD3e (HIT3a), TCRα/β (IP26) and CD69 (FN50) from Biolegend (Beijing, China) for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Cell counting was conducted using a BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) and data was obtained and analyzed with BD Accuri C6 Software (BD).

RNA extraction and TCR repertoires library preparation

RNAprep Pure Cell/Bacteria Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) was used to extract RNA from the isolated lymphocytes. The quality and quantity of RNA were measured by using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a T100TM Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Inc., CA, USA). A total of 200 ng RNA was performed in the reverse transcription reaction. TCRβ repertoire library was prepared by two-round multiplex PCR using specific primers designed for functional V and C gene segments of TCRβ chain (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). TCRβ chain repertoire amplification was performed as described in our previous work [18]. The PCR products were loaded on 1% TBE-Agarose for gel electrophoresis and purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform was used for high-throughput sequencing of TCRβ chain repertoire.

Data processing

Paired-end V, D and J sequences of TCRβ chain were identified using BLAST Plus on IMGT database (http://www.imgt.org/) by a standard algorithm after filtering the low-quality reads. Heatmaps and circular plots were created to reflect the frequencies of V, J gene segments and paired V–J combinations, respectively. Gini coefficient, Shannon diversity and Rank-abundance were used for assessing the richness and diversity of TCR as previously described [19,20,21].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) using a 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was for two groups comparisons. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the subjects

Demographic characteristics and baseline clinical features of participants including gender, age, past medical history and biochemical data were summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed with gender, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, total cholesterol and history of smoking between two groups. The concentration of cTnI was significantly higher in AMI patients than that in healthy controls (Table 1). We also found that levels of peripheral WBC and neutrophils were significantly elevated in AMI patients (Fig. 1a, b). Interestingly, the percentage of lymphocytes was significantly decreased in AMI patients compared to controls (Fig. 1c), and the concentration of cTnI was negatively associated with lymphocytes levels (Fig. 1d). No significant variation in monocytes levels was verified in AMI patients (Fig. 1e).

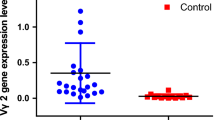

AMI leads to αβ T cells activation. Peripheral blood samples were obtained from 30 healthy controls and 30 AMI patients. a The count of WBC was measured from peripheral blood samples. The percentage of neutrophils (b), lymphocytes (c), monocytes (e) was detected by Sysmex XN in our clinical laboratory. d The correlation between cTnI level and lymphocytes was calculated in AMI patients. Spearman’s correlation coefficient r = − 0.5874, P = 0.0006 (n = 30). f The percentage of αβ T cells from peripheral blood was analyzed by flow cytometry. g αβ T cells were gated and tested for expression of CD69

AMI activates αβT cells in AMI patients

To explore the status of αβ T cells in response to AMI, we measured the population of αβ T cells from peripheral blood by using flow cytometer. As expected, a lower percentage of peripheral αβ T cells were observed in AMI patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1f). To determine whether AMI activates αβ T cells, we also examined the expression of CD69 of αβ T cells in peripheral blood. Strikingly, there was, compared to controls, obvious increase in CD69 level of αβ T cells, indicating that a significant activation of peripheral αβ T cells occurred in AMI patients (Fig. 1g).

Profiling of V, D and J gene segments usage after AMI

Next, the usages patterns of V, D and J gene were measured by NGS approach based on multiplex PCR from peripheral αβ T cells. This yielded on 5.13 × 106 to 11.11 × 106 productively TCRβ blast reads per sample. The total number of TCRβ CDR3 reads was 0.57 × 104 to 7.60 × 104, with an average of 3.70 × 104 CDR3 clonotypes per sample (Additional file 2: Table S1). In addition, a total of 56 distinct V gene segments and 14 distinct J gene segments from all samples (Additional file 3: Table S2). Overall, the usages of V and J gene segments were dominated by high-frequency segments in healthy controls, which top10 TRBV accounted for 90.83% and top5 TRBJ accounted for 72.98%. In contrast, top10 TRBV only accounted for 62.77% and top5 TRBJ accounted for 58.83% in AMI patients (Fig. 2a, b). The most frequent V gene segments were TRBV20 (17.51% in healthy controls, 12.77% in AMI patients). The most frequent J gene segments were TRBJ2-1 (18.43% in healthy controls, 15.95% in AMI patients). Generally, the usage patterns and frequencies of most V and J genes were similar between healthy controls and AMI patients (Fig. 2c–e). However, these were significant differences in frequency of TRBV10-3, TRBV11-2, TRBV9, TRBV3-1, TRBV6-7 and TRBJ5-1 (Fig. 2f, g).

The usage patterns of V and J gene segments after AMI. High-throughput sequencing of 10 PCR products (five controls and five AMI patients) amplified from peripheral lymphocytes for TCRβ repertoire analysis. The distribution of Top10V (a) and Top5J (b) genes expression. Colors indicate Top10/Top5 clones (each color represents a clone); grays represent non-Top10/Top5 clones. c Heatmaps of hierarchical clustering of V and J gene segments frequencies. The frequencies of V (d, f) and J (e, g) gene segments usage that had significant differences between healthy controls and AMI patients

Lower V–J and V–D–J combinations in AMI patients

Furthermore, we also analyzed the composition of paired V–J combinations and paired V–D–J combinations (Additional file 4: Table S3, Additional file 5: Table S4). Analysis of high-throughput sequencing of TCRβ chain repertoire led to the identification of 708 distinct V–J combinations and 1304 distinct V–D–J combinations (Fig. 3a). Of note, AMI significantly resulted in reduced the clonotypes of V–J and V–D–J combinations (Fig. 3b, c). The volcano plots were generated according to the usage frequency of V–J combinations and V–D–J combinations. Compared to controls, there were 39 V–J combinations and 51 V–D–J combinations that exhibited significantly abnormal usage in AMI patients. Interestingly, the frequencies of all altered V–J and V–D–J combinations were elevated in AMI patients, compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3d).

The usage patterns of V–J and V–D–J combination. a Circular plots representing TCRβ loci were identified from αβ T cells. The clonotypes of V–J (b) and V–D–J (c) combinations were counted from sequencing data. d Volcano plots showing the comparison of V–J and V-D–J combinations between healthy controls and AMI patients (red dots refer to the differentially expressed combinations with statistical significance)

AMI induces a diminished diversity of CDR3 AA

Types of CDR3 AA clones determine the diversity of the TCR repertoires. In the current study, 360,274 distinct CDR3 AA clonotypes was identified (Additional file 6: Table S5). Although total TCR CDR3 AA clones were distinguishing among different individual, AMI, of note, led to obvious decreases in TCRβ base sequence clonotypes and CDR3 AA clonotypes (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a, b and Fig. 4a, b). Next, we quantified overlap of TCRβ base sequence and CDR3 AA clonotypes among different sample and found that overlap of TCRβ base sequence and CDR3 AA clonotypes in AMI patients were substantially higher than it in controls (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a, c and Fig. 4a, c). Gini coefficient, Simpson index and Shannon diversity suggested remarkably lessened CDR3 AA diversity in AMI patients (Fig. 4d–f). Rank-abundance analysis also exhibited a shrunken CDR3 AA richness and evenness in AMI patients (Fig. 4g).

The diversity of TCRβ CDR3 AA clonotypes. a Quantification (plot grays) and frequencies (plot colors) of overlapping TCRβ clonotypes. Light grays indicate the overlapping clonotypes, while dark grays indicate the total clonotypes per sample. Comparison of TCRβ repertoire diversity by total CDR3 AA clonotypes (b), shared CDR3 AA clonotypes (c), Gini coefficient (d), Simpson index (e) and Shannon index (f) between healthy controls and AMI patients. g Rank-Abundance analysis of CDR3 AA clonotypes among different samples

Resetting of the CDR3 AA in AMI patients

In order to investigate the reconstitution of CDR3 AA, Bhattacharyya distance was used to assess the similarity. As expected, Bhattacharyya distance clearly demonstrated a high similarity of CDR3 AA in AMI patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 5a). In addition, we evaluated the frequency of CDR3 AA usage in different samples (Additional file 7: Table S6). Of note, comparison of CDR3 AA usage showed that AMI induced aberrant CDR3 AAs usage of phenylalanine (downregulation), histidine (downregulation), leucine (downregulation) and arginine (upregulation) (Fig. 5b, c). However, there were no significant differences observed in length tendency in CDR3 AA length after AMI (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

Discussion

Aberrant T cell function caused by AMI usually results in acute and chronic inflammatory processes that impair cardiac function [7, 22, 23]. Currently, despite a profound understanding of the adaptive immune system, and specifically the T cell response, in AMI, much less is known about TCR rearrangement. Accumulating evidence demonstrate that TCR repertoires will be rapidly reconstituted in response to endogenous and exogenous stimuli for immunosurveillance and immunoregulation [24,25,26]. Our preceding study indicates that TCR acts more like a “commander” than like an “executor” to monitor immune microenvironment [18]. Therefore, identifying and tracking TCR immune repertoires provide a novel method to understand the association between T lymphocytes and AMI injury.

The vast majority of data support that patients suffering AMI have significantly increased peripheral blood T cell activation though the decrease of T lymphocyte count occurred in the circulatory system [10, 11, 27, 28]. Following AMI, CD4+ T cells can be activated, by presentation of myocardial peptides by dendritic cell [29]. It is considered that this activation process occurs within days and requires an intact T-cell receptor repertoire. Recognition of cardiac autoantigens by TCR, presumably, is critical for maintaining the balance of control of AMI injury vs. T cell response, and facilitate wound healing of the myocardium [29]. Consistent with previous studies, our results revealed reduced percentage and enhanced activation of αβ T cells in peripheral blood after AMI, demonstrating the crucial role of αβ T cells in AMI [11, 30]. Surely, enhanced activation of αβ T cells can be attributed to AMI injury and heart failure. Nevertheless, the cause of diminishing αβ T cells in the process of AMI is still uncertain. It is speculated that several T cell subpopulations which exert immunosuppressive effect on myocardial inflammation vanish in this course, and TCR immune repertoires rearrangement occurs in order to recognize cardiac autoantigens, resulting T cells activation and myocardium injury. In this course, a massive activated T cells itself provides exact identification synergistically with other immunocytes to promote the pathogenesis.

Our work revealed an intact TCRβ profile of V, D and J genes usage and the distribution of CDR3 AA clonotypes after AMI. In the current study, the frequencies of V and J genes exhibited more centralized distribution though the majority of V and J genes were similar between healthy controls and AMI patients. It is noteworthy that the high clonal expansion frequencies of the TRBV10-3, TRBV11-2 and the low clonal expansion frequencies of the TRBV9, TRBV3-1, TRBV6-7 and TRBJ5-1 were determined in AMI patients. It is suggested that such expand TRBV clones may be reactive T cell clones directed against AMI, while such lessened TRBV/TRBJ clones may act as immunosuppressive T cell clones in AMI. Moreover, AMI induced a diminished composition of V–J/V–D–J combination. Interestingly, the frequencies of all V–J/V–D–J combinations that had significant differences after AMI were upregulated unanimously, partly as a result of reduced composition of V–J/V–D–J combination and partly because AMI restrains immunosuppressive T cell subsets emergence. These data were consistent with the results in Fig. 1, which indicate that a lower percentage of peripheral αβ T cells was observed in AMI patients.

CDR3, composed of variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) domains from the terminal of the V domain to the beginning of the J domain, is considered as a critical region to recognize antigen. The specificity and diversity of TCR repertoires is dependent of CDR3 AA clonotypes [31, 32]. In this work, obviously decreased CDR3 clonotypes and altered CDR3 AAs were observed in AMI patients, suggesting that AMI led to a shrunken TCRβ diversity and VDJ recomposition. Among AMI patients, the proportion of shared CDR3 AA was obviously elevated compared to that among healthy controls, which imply that AMI induced the usage of several key high-frequency CDR3 AAs. Our observation of transformation of TCRβ repertoire after AMI provides evidence of AMI-associated immune repertoire in AMI injury progression. These results indicate that transformation of TCR immune repertoires is indispensable for antigen recognition in the adaptive immune system for myocardial injury.

Undoubtedly, AMI-responsive TCRβ immune repertoire represents a “footprint” of immune microenvironment in peripheral blood, which will be conducive to better understanding of the function of αβ T cell in myocardial injury after AMI. However, the mechanism and effect of TCRβ reconstitution in T cell activation are still not clear, and how TCRβ immune repertoire modulates the inflammatory milieu needs to be further investigated. Of note, a recent study finds the difference in expression pattern and clonality of TCR γδ T cells between AMI patients and healthy individuals, reflected by the obviously restricted TCR γδ subfamilies expression in γδ T cells from AMI patients [33]. The preceding data along with our result indicate an important role of αβ and γδ T cells in AMI injury, and reconstitution of TCR immune repertoires participate in modulation of inflammatory status.

Conclusions

Our work first reveals the characteristic of the TCRβ immune repertoire after AMI. Through its tracking of the kinetics of the reconstitution of TCRβ, we find significantly restricted TCRβ immune repertoire and the discrepancy in the expression of αβ T subsets, which may be related to the immune response and clinical outcome. These data provide a novel insight to identify signatures of AMI-associated immune microcircumstance, which will accelerate discoveries of novel immunotherapy for AMI patients.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

acute myocardial infarction

- TCR:

-

T cell receptor

- CDR3:

-

complementary determined regions 3

- AA:

-

amino acids

- MHC:

-

major histocompatibility complex

- APCs:

-

antigen-presenting cells

- NSG:

-

next-generation sequencing

- cTnI:

-

cardiac troponin-I

- PCI:

-

primary percutaneous intervention

- TRBV:

-

TCRβ V gene

- TRBJ:

-

TCRβ J gene

- IMGT:

-

ImMunoGeneTics

References

Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–19.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–292.

Shepard D, VanderZanden A, Moran A, Naghavi M, Murray C, Roth G. Ischemic heart disease worldwide, 1990 to 2013: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2013. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:455–6.

Jia L, Zhu L, Wang JZ, Wang XJ, Chen JZ, Song L, Wu YJ, Sun K, Yuan ZY, Hui R. Methylation of FOXP3 in regulatory T cells is related to the severity of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228:346–52.

Lu Y, Li L, Yan H, Su Q, Huang J, Fu C. Endothelial microparticles exert differential effects on functions of Th1 in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:5396–404.

Zhang Y, Lin P, Jiang H, Xu J, Luo S, Mo J, Li Y, Chen X. Extensive serum biomarker analysis in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Cytokine. 2015;76:356–62.

Hofmann U, Frantz S. Role of T-cells in myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:873–9.

Stephenson E, Savvatis K, Mohiddin SA, Marelli-Berg FM. T-cell immunity in myocardial inflammation: pathogenic role and therapeutic manipulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:3914–25.

Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Pistoia V. Immunosuppressive treatments in acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:59–67.

Turner NA. Inflammatory and fibrotic responses of cardiac fibroblasts to myocardial damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;94:189–200.

Napoleao P, Selas M, Freixo C, Carmo MM, Viegas-Crespo AM, Ferreira RC, Pinheiro T. T lymphocytes alterations are associated with oxidized LDL, troponin T, white blood cells and C-reactive protein during acute myocardial infarction. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2013;55:349–58.

Roche PA, Cresswell P. Antigen processing and presentation mechanisms in myeloid cells. Microbiol Spectr. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0008-2015.

Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:227–42.

Singhal A, Mori L, De Libero G. T cell recognition of non-peptidic antigens in infectious diseases. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:620–31.

Poschke I, Flossdorf M, Offringa R. Next-generation TCR sequencing—a tool to understand T-cell infiltration in human cancers. J Pathol. 2016;240:384–6.

Hou D, Ying T, Wang L, Chen C, Lu S, Wang Q, Seeley E, Xu J, Xi X, Li T, et al. Immune repertoire diversity correlated with mortality in avian influenza A (H7N9) virus Infected patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33843.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Joint ESCAAHAWHFTFftUDoMI, Katus HA, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–35.

Liang Q, Liu Z, Zhu C, Wang B, Liu X, Yang Y, Lv X, Mu H, Wang K. Intrahepatic T cell receptor beta immune repertoire is essential for liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30067.

Chen Y, Xu Y, Zhao M, Liu Y, Gong M, Xie C, Wu H, Wang Z. High-throughput T cell receptor sequencing reveals distinct repertoires between tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues in HBV-associated HCC. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1219010.

Birtel J, Walser JC, Pichon S, Burgmann H, Matthews B. Estimating bacterial diversity for ecological studies: methods, metrics, and assumptions. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125356.

Sims JS, Grinshpun B, Feng Y, Ung TH, Neira JA, Samanamud JL, Canoll P, Shen Y, Sims PA, Bruce JN. Diversity and divergence of the glioma-infiltrating T-cell receptor repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3529–37.

Kaplan A, Altara R, Eid A, Booz GW, Zouein FA. Update on the protective role of regulatory T cells in myocardial infarction: a promising therapy to repair the heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2016;68:401–13.

Novak J, Dobrovolny J, Tousek P, Kocka V, Teringova E, Novakova L, Widimsky P. Potential role of invariant natural killer T cells in outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:663–5.

Maryanski JL, Casanova JL, Falk K, Gournier H, Jaulin C, Kourilsky P, Lemonnier FA, Luthy R, Rammensee HG, Rotzschke O, et al. The diversity of antigen-specific TCR repertoires reflects the relative complexity of epitopes recognized. Hum Immunol. 1997;54:117–28.

Attaf M, Huseby E, Sewell AK. alphabeta T cell receptors as predictors of health and disease. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:391–9.

Boudinot P, Marriotti-Ferrandiz ME, Pasquier LD, Benmansour A, Cazenave PA, Six A. New perspectives for large-scale repertoire analysis of immune receptors. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2437–45.

Zhai S, Zhang L, Dang S, Yu Y, Zhao Z, Zhao W, Liu L. The ratio of Th-17 to Treg cells is associated with survival of patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Viral Immunol. 2011;24:303–10.

Methe H, Brunner S, Wiegand D, Nabauer M, Koglin J, Edelman ER. Enhanced T-helper-1 lymphocyte activation patterns in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1939–45.

Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, Podolskaya A, Bauersachs J, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2012;125:1652–63.

Hosono M, de Boer OJ, van der Wal AC, van der Loos CM, Teeling P, Piek JJ, Ueda M, Becker AE. Increased expression of T cell activation markers (CD25, CD26, CD40L and CD69) in atherectomy specimens of patients with unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168:73–80.

Armstrong KM, Piepenbrink KH, Baker BM. Conformational changes and flexibility in T-cell receptor recognition of peptide-MHC complexes. Biochem J. 2008;415:183–96.

Fozza C, Barraqueddu F, Corda G, Contini S, Virdis P, Dore F, Bonfigli S, Longinotti M. Study of the T-cell receptor repertoire by CDR3 spectratyping. J Immunol Methods. 2017;440:1–11.

Chen XM, Zhang T, Qiu D, Feng JY, Jin ZY, Luo Q, Wang XY, Wu XL. Gene expression pattern of TCR repertoire and alteration expression of IL-17A gene of gammadelta T cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Transl Med. 2018;16:189.

Authors’ contributions

KW contributed to the study conception and design; DL, QL, CZ and YS performed the experiments; LH, QL and BW analyzed the data; KW contributed to manuscript drafting and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human subjects: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Animals: Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province Project (ZR2016HP17) and the Postdoctoral Application Research of Qingdao Project (2016063).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Two-round nested amplicon arm-PCR for TCRβ immune repertoire. n = 5 per group. Fig. S2. The clonotypes analysis of TCRβ base sequence. a Quantification (plot grays) and frequencies (plot colors) of base sequence clonotypes. Light grays indicate the overlapping clonotypes, while dark grays indicate the total clonotypes per sample. b Comparison of total clonotypes of TCRβ base sequence. c The percentage of overlapping base sequence between healthy controls and AMI patients. Fig. S3. The distribution of CDR3 AA length between healthy controls and AMI patients. n = 5 per group.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

The analysis of TCRβ immune repertoire sequencing data.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

The distribution of V and J gene segments in each sample.

Additional file 4: Table S3.

The distribution of V-J combinations in each sample.

Additional file 5: Table S4.

The distribution of V-D-J combinations in each sample.

Additional file 6: Table S5.

The distribution of CDR3 AA clonotypes in each sample.

Additional file 7: Table S6.

The distribution of AA usage in CDR3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Hu, L., Liang, Q. et al. Peripheral T cell receptor beta immune repertoire is promptly reconstituted after acute myocardial infarction. J Transl Med 17, 40 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1788-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1788-4