Abstract

Background

Although medical requirements are urgent, no effective intervention has been proven for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). To facilitate the development of new therapeutics, we systematically reviewed the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for CFS/ME to date.

Methods

RCTs targeting CFS/ME were surveyed using two electronic databases, PubMed and the Cochrane library, through April 2019. We included only RCTs that targeted fatigue-related symptoms, and we analyzed the data in terms of the characteristics of the participants, case definitions, primary measurements, and interventions with overall outcomes.

Results

Among 513 potentially relevant articles, 56 RCTs met our inclusion criteria; these included 25 RCTs of 22 different pharmacological interventions, 29 RCTs of 19 non-pharmacological interventions and 2 RCTs of combined interventions. These studies accounted for a total of 6956 participants (1713 males and 5243 females, 6499 adults and 457 adolescents). CDC 1994 (Fukuda) criteria were mostly used for case definitions (42 RCTs, 75.0%), and the primary measurement tools included the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS, 35.7%) and the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36, 32.1%). Eight interventions showed statistical significance: 3 pharmacological (Staphypan Berna, Poly(I):poly(C12U) and CoQ10 + NADH) and 5 non-pharmacological therapies (cognitive-behavior-therapy-related treatments, graded-exercise-related therapies, rehabilitation, acupuncture and abdominal tuina). However, there was no definitely effective intervention with coherence and reproducibility.

Conclusions

This systematic review integrates the comprehensive features of previous RCTs for CFS/ME and reflects on their limitations and perspectives in the process of developing new interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is a long-term debilitating illness characterized by medically unexplained, severe and disabling fatigue that persists at least 6 months and is not improved by rest, accompanied by post exertion malaise (PEM) and unrefreshing sleep [1]. Patients with CFS/ME cannot carry out their normal social routines, work or leisure activities, and some of them are even home- or bed-bound. They experience lower health-related quality of life than those experiencing depression or stroke patients [2]. The medical impact includes the high prevalence in the working age population and particularly the high risk of suicide, which is approximately 7-fold higher than that in healthy controls [3]. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report in 2015 estimated 17 to 24 billion dollars for total economic costs annually and 836,000 to 2.5 million sufferers of CFS/ME in the USA [1]. The worldwide prevalence of CFS/ME is estimated to be approximately 1–2% [4].

To date, diverse studies, including those of the immune system, metabolomics, endocrine system, gut microbiota and nervous system, have been conducted to determine the pathological mechanisms of CFS/ME [5]. This illness is expected to be a complex, multisystem neuroimmune disease [6]. Recently, some novel clues for CFS/ME were found, such as higher levels of immunosuppressive cytokines, especially TGF-β [7], an altered composition of the gut microbiome [8], and nanoelectronic assays for potential diagnostic biomarkers [9]. However, the clear mechanisms of CFS/ME or its objective diagnostic markers have not yet been found.

In addition, despite numerous approaches with various interventions, no definitively effective treatment has been approved for patients with CFS/ME [10]. Through a large-scale clinical study (called the PACE trial), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) were recommended as effective therapies for CFS/ME; however, there is debate and criticism by both scientists and patients [11]. A recent trial using a monoclonal antibody, rituximab, also did not show promising results [12]. At present, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has proposed symptomatic treatments as an alternative [13]. New approaches and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are now urgently needed with rigorous experimental designs for therapeutic developments combating CFS/ME.

To facilitate those tasks in the future, this systematic review aimed to integrate the features of the trials for CFS/ME conducted so far in terms of patient characteristics, case criteria, outcome measurements and interventions with overall results.

Methods

Data sources and keywords

A systematic literature survey was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [14] using two electronic literature databases, PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and the Cochrane library (http://www.cochrane.org), through April 2019. The search terms used were encephalomyelitis, ME, chronic fatigue syndrome, CFS, ME/CFS, randomized controlled trial and clinical trial. The trial type was limited to RCTs, and all languages were included.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were screened according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) RCTs or randomized controlled crossover trials, (2) patients with CFS/ME as participants, (3) an evaluation of the efficacy of the intervention for CFS/ME treatment, and (4) fatigue-related primary measurement or main outcome. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles with no full text, (2) the number of participants was less than 45 (less than 23 in a crossover trial), (3) studies without mention of the case definition or the characteristics of participants and (4) studies with a Jadad score less than 3 points.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted data on the number of participants, sex ratio, mean age, ME/CFS diagnostic case definition, intervention category, treatment period, dose, control and outcome measurement tool. We also obtained the outcome data with a statistical analysis of the treatment effectiveness compared to the control.

To assess the quality of RCTs, the Jadad scale was used [15]. The Jadad scale is a five-point scale in which descriptions of randomization, double-blinding, or withdrawals and drop-outs receive one point each. Additionally, a description of the appropriate methods of randomization or blinding receives one point. If the method of randomization or blinding is inappropriate, one point is deducted. Consequentially, trials with ≥ 3 points are considered high quality and were included for further data extraction.

Judgment of the statistical efficiency of the intervention

We judged the intervention efficacies as ‘Significant’ or ‘Not significant’ based on the data presentations of the original articles. In general, ‘Significant’ meant that the intervention reached statistical significance (intervention vs. control, P < 0.05 or Cohen’s d > 0.8) according to the primary measurement at the planned time point outcome assessment. We defined ‘partially significant’ for the following cases: (1) only part of the main outcomes was statistically significant, or (2) statistical significance was observed only at certain time points without a description of the fixed period for final assessment.

Data analysis

This study basically does not need to apply statistical analysis. Regarding the number of participants, age and treatment period in two populations (adults and adolescents), data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD).

Results

Characteristics of RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria

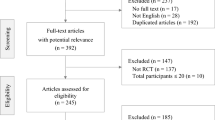

From the PubMed and Cochran databases, a total of 513 articles were initially identified, and 56 articles ultimately met the inclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 1). Fifty-one RCTs (91.1%) were conducted for adult patients, while 5 RCTs (8.9%) were conducted for the adolescent population (Table 1). The majority of RCTs were conducted in 3 countries: the UK (n = 16), the Netherlands (n = 14), and the USA (n = 9). Regarding interventions, 29 RCTs (51.8%) conducted non-pharmacological interventions, 25 RCTs (44.6%) conducted pharmacological interventions and 2 RCTs conducted a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (Tables 2 and 3).

Characteristics of participants and case definitions for inclusion criteria

In 56 RCTs, a total of 6956 participants (1713 males and 5243 females, 6499 adults with a mean age of 40.2 ± 4.0 years and 457 adolescents with a mean age of 15.5 ± 0.3 years) were enrolled. Fifty-five RCTs (98.2%) adapted at least one of the following CFS case definitions: CDC 1994 (Fukuda) criteria (42 RCTs), Oxford 1991 (Sharpe) criteria (13 RCTs), CDC 1988 (Holmes) criteria (3 RCTs), Lloyd 1988 criteria (2 RCTs), and Schluederberg 1992 (2 RCTs). There were 12 RCTs with two case definitions for inclusion criteria (Table 1).

Main outcome measurement

A total of 31 primary measurement tools were used to assess the main outcome in 56 RCTs. The Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) was the most frequently used (35.7%), and others included the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36, 32.1%), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP, 14.3%), Chalder Fatigue Scale (14.3%), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, 10.7%) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI, 8.9%). There were 29 RCTs that used multiple primary measurements (Table 1).

RCTs with pharmacological interventions

A total of 22 different medications were evaluated by comparison with placebo in 25 RCTs (23 for adults, 2 for adolescents). These medications included psychiatric drugs (n = 8), cortisol (n = 5), immunomodulators (n = 4), and mitochondrial modulators (n = 3). The mean treatment period was 10.8 ± 6.8 weeks (11.0 ± 7.0 weeks for adults, 8.5 ± 0.7 weeks for adolescents). Three RCTs showed positive results with statistical significance: two with immunomodulators (Staphypan Berna [25] and poly(I):poly(C12U) [27]) and one with CoQ10 + NADH [34] (Table 2).

RCTs with non-pharmacological interventions

There were 29 RCTs in the non-pharmacological category (26 for adults, 3 for adolescents) with 19 kinds of interventions, mainly CBT (n = 12), exercise (n = 6), and self-care (n = 5). The mean treatment period was 18.5 ± 8.9 weeks (17.1 ± 7.1 weeks for adults, 30.7 ± 15.1 weeks for adolescents). Of the 12 CBT subcategories, 6 RCTs showed statistical effectiveness of CBT compared to the control [41, 44, 46, 49, 50, 52]. In addition, 4 RCTs of graded-exercise-related therapies [46, 53, 55, 56] and 3 RCTs of integrative, consumer-driven rehabilitation [64], acupuncture [65] and abdominal tuina [67] showed a significantly effect of the intervention compared to the control (Table 3).

RCTs with pharmacological and non-pharmacological combined interventions

Two RCTs were conducted to assess the synergistic effects of 4 different interventions (GET + fluoxetine, dialyzable leukocyte extract (DLE) + CBT). No synergistic efficacy was observed (Table 4).

Discussion

Since CFS was first shed light on and defined in the 1980s [72], numerous studies on its pathophysiology and treatment have been conducted. Nonetheless, CFS/ME is still poorly understood. To support future studies for CFS/ME treatments, we systematically reviewed 56 RCTs to investigate characteristics such as participants, case definitions, interventions and primary measurements. In addition, we found a trend in the interventions used as well as their overall results.

The sex ratio of the participants was male 1 vs. female 3 (1713/5143, except one RCT had recruited only females). An epidemiological feature of CFS/ME is the higher prevalence in women and even in adolescent populations [73] (Table 1). The diagnostic criteria of the RCTs were diverse. To date, no objective diagnostic parameters or biomarkers exist; thus, the use of criteria for case definitions is the only way to diagnose CFS/ME [74]. Two major case definition tools, Oxford 1991 (Sharpe) and CDC 1994 (Fukuda), have been applied predominantly (Table 1). The former was mostly applied in RCTs conducted before the mid-2000s and preferred by UK studies (10 of the relevant 12 RCTs). On the other hand, CDC 1994 (Fukuda), revised after CDC 1988 (Holmes), has been employed most frequently and steadily by worldwide researchers since 1994.

A total of 56 RCTs included 25 pharmacological, 29 nonpharmacological and 2 combined interventions (Table 1). The mean treatment period of the RCTs with non-pharmacological interventions was longer than that with medication, especially for adolescents (total: 18.5 ± 8.9 vs. 10.8 ± 6.8, adolescent: 30.7 ± 15.1 vs. 8.5 ± 0.7, Table 1). Periodically, the trials gradually increased, with 13 trials in the 1990s, 19 trials in the 2000s and 24 trials in the 2010s. The pharmacological RCTs were predominant in the 1990s and 2000s, while nonpharmacological interventions became predominant in the 2010s (pharmacological:non-pharmacological ratio from 20:14 to 7:17) (data not shown). This trend might be related to the poorly understood etiology of this disease, the knowledge of which is vital for the proper development of therapeutic medications [75].

In the early days, immunological, virological, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunctional and psychiatric hypotheses were mainly proposed for the pathophysiology of CFS/ME [76]. Accordingly, immunomodulators, cortisol medications, and psychiatric drugs were frequently employed for medication (Table 2). Although some immunomodulators have presented notable positive effects in RCTs [25, 27], they are rarely administered clinically because of potential adverse effects and insufficient evidence of efficacy [77, 78]. Similarly, hydrocortisone or fludrocortisone treatments to modulate the dysfunction of the HPA axis have failed to show the repeatability and coherence of effectiveness [28,29,30,31,32]. Psychiatric drugs, especially antidepressants, have been frequently and steadily employed in RCTs and in the clinical fields [79]. In fact, depressive mood is a common comorbid symptom in CFS/ME patients [80, 81]. However, depression and CFS/ME are well defined as two different diseases. For example, major depressive disorder has a typical pathology of insufficient activity of serotonin (5-HT), while hyperactivity of 5-HT is a feature of CFS/ME [82, 83]. Although there is conflicting evidence, antidepressants are currently not recommended for patients with CFS/ME without depressive symptoms [73]. However, mitochondrial dysfunction and ATP depletion have recently been regarded as weighty features of CFS/ME [5, 84]. Among the two RCTs with those interventions, KPAX002 failed to demonstrate its effects on CFS/ME [33], but NADH + CoQ10 showed positive effects on fatigue [34].

Non-pharmacological interventions could be subgrouped into CBT, exercise such as GET, self-instruction with/without guidance, rehabilitation and acupuncture (Table 3). In fact, only CBT and GET were tested for clinical efficacy in CFS/ME in the 1990s. Until 2010, mostly positive outcomes were reported for CBT and GET (3 of 5 RCTs in the 1990s and 4 of 5 RCTs in the 2000s). These RCT-derived results supported and recommended CBT and GET as treatment options for patients suffering from CFS/ME. CBT is a psychosocial therapy that has been applied to diverse mental disorders, including depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders and psychosis [85,86,87,88]. Until 2010, RCTs for CBTs were conducted mostly in the classic form of face-to-face therapy between therapists and patients with CFS/ME [49,50,51,52]. Subsequently, various forms of CBT have been employed, such as group CBT [42, 48], internet-based CBT [41, 44], and family-focused CBT [47]. Contrary to the positive outcomes in the 1990s and 2000s, more recent CBT trials have failed to show consistent benefits in patients with CFS/ME: 5 of 8 RCTs of CBT did not show significant effects in our data. Another frequently applied non-pharmacological intervention is GET, a physical activity with a gradual increase in intensity. The hypothesis of GET effectiveness is based on psychiatric assistance through motivating patients to overcome their negative perceptions as well as through an intensification of physical fitness [55]. In our data, 5 of 6 RCTs with graded-exercise-related therapies presented positive outcomes; however, the clinical usefulness of GET is highly controversial [89]. One survey reported that 79% of CFS/ME participants felt that GET worsened their health status [90]. Furthermore, GET was criticized due to the conflict with PEM, a particularly essential symptom of CFS/ME according to the IOM diagnostic criteria [91]. Both CBT and GET have limitations and have received criticism more recently because they are based on psychiatric views, which is contrary to the fact that CFS/ME is a physical illness based on accumulated evidence from scientists as well as patients and physicians [1].

RCTs of alternative medicines and self-therapies for CFS/ME have increased since the late 2000s. Regarding RCTs of alternative medicines such as acupuncture, qigong, and abdominal tuina [54, 65,66,67], 10 RCTs were selected in our review process, but 6 were excluded due to low quality (a Jadad score less than 3) or too few participants. A systematic review also presented the limitations of acupuncture treatment due to the low quality of RCTs and the weak strength of evidence along with the weak potential to improve the symptoms of CFS/ME [92]. There were also 5 RCTs with self-care therapies, including guided self-instructions and fatigue self-management (Table 3). Among them, 2 guided self-instructions, using a similar protocol of CBT, presented partially positive results [58, 60]. For psychiatric disorders, the therapeutic relationship between patients and therapists is known to play an important role in counseling treatments, and these positive outcomes from interventions with minimized involvement of therapists support an assertion of the nonpsychological aspect of CFS/ME [93].

To date, the overall results of RCTs have been more positive for non-pharmacological interventions than for medications (Fig. 2). Among diverse interventions, psychiatric approaches were predominant in both pharmacological interventions and non-pharmacological interventions; however, they failed to show the repeatability of positive outcomes. Moreover, there is consensus for the complexity of the physical illness of CFS/ME, as evidenced by accumulating scientific findings [1]. Accordingly, to explore the pathophysiology of CFS/ME, new systematic research strategies are essential for developing fundamental treatments, especially for pharmaceutical interventions, although most drug-based RCTs have failed so far.

Graphical display for statistical significance of interventions. ‘Significant’ means that the treatment achieved statistical significance (intervention vs. control, P < 0.05 or Cohen’s d > 0.8) according to the primary measurement at the planned time point outcome assessment. ‘Partially significant’ means (1) only the part of the main outcomes was statistically significant or (2) statistical significance was observed only at certain time points without a description of the fixed period for final assessment

Our review has some limitations. We searched literatures from PubMed and Cochrane library. Although these two databases are the major resources for scientific articles especially derived from RCTs, there would be a possibility of further information in other databases. In order to produce confident data, we excluded the too small-scale RCTs (< 45 participants), however this strategy also has a risk to loss any valuable information. In addition, only 9 of 56 RCTs had presented fragmentary data related to blood parameters. We could hardly find any practical indications due to very heterogenous parameters and no significant correlation with changes of fatigue symptoms. The identification of the blood-based biomarkers is necessary for diagnosis as well as classification of CFS/ME and should be applied to clinical trials in the future. Nevertheless, this is the first systematic review of RCTs targeting CFS/ME regardless of language, and this review shows the comprehensive features of CFS/ME. Our review offers fundamental information for future research on the pathophysiology of and new treatments for CFS/ME.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive integration of previous RCTs for CFS/ME. Our data include characteristics of RCTs such as participants, case definitions, interventions and primary measurements. In addition, we found trends in the interventions used as well as in the overall results. Psychological treatments were predominant and had limitations curing CFS/ME. An exploration of the pathophysiology of CFS/ME and better development of treatments are needed.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are available in the public domain.

Change history

23 December 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT:

-

cognitive behavior therapy

- CFS:

-

chronic fatigue syndrome

- CGI:

-

Clinical Global Impression

- CHQ (-CF):

-

Child Health Questionnaire (-Child Form)

- CIS:

-

Checklist Individual Strength

- CPRS:

-

Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale

- DLE:

-

dialyzable leukocyte extract

- FIS:

-

Fatigue Impact Scale

- FITNET:

-

Fatigue in Teenagers on the interNET

- FSM:ACT:

-

Fatigue Self-Management with web diaries and actigraphs

- FSM:CTR:

-

Fatigue Self-Management with paper diaries and pedometers

- FSS:

-

Fatigue Severity Scale

- GET:

-

graded exercise therapy

- GHQ:

-

General Health Questionnaire

- HAMD:

-

Hamilton rating scale for Depression

- HC:

-

healthy control

- HRQL:

-

health-related quality of life

- iCBT:

-

Internet-based CBT

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky Performance Score

- MFI:

-

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

- MFS:

-

Mental Fatigue Scale

- MRT:

-

multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment

- POMS:

-

Profile of Mood States

- QoL:

-

quality of life

- SAR:

-

school attendance rate

- SAS:

-

Self-rating Anxiety Scale

- SF-36:

-

36-item Short Form health survey

- SIP:

-

Sickness Impact Profile

- MC:

-

medical care

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale

References

Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: redefining an illness. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health.

Hvidberg MF, Brinth LS, Olesen AV, Petersen KD, Ehlers L. The health-related quality of life for patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132421.

Kapur N, Webb R. Suicide risk in people with chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1596–7.

Johnston S, Brenu EW, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. The prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:105–10.

Missailidis D, Annesley SJ, Fisher PR. Pathological mechanisms underlying myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Diagnostics. 2019;9(3):E80.

Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30:223–49.

Montoya JG, Holmes TH, Anderson JN, Maecker HT, Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Valencia IJ, Chu L, Younger JW, Tato CM, Davis MM. Cytokine signature associated with disease severity in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(34):E7150–8.

Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, Levine SM, Ley RE, Hanson MR. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):30.

Esfandyarpour R, Kashi A, Nemat-Gorgani M, Wilhelmy J, Davis RW. A nanoelectronics-blood-based diagnostic biomarker for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(21):10250–7.

Whiting P, Bagnall AM, Sowden AJ, Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Ramírez G. Interventions for the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1360–8.

ShepherdCB PACE. trial claims for recovery in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome—true or false? It’s time for an independent review of the methodology and results. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(9):1187–91.

Fluge O, Risa K, Lunde S, Alme K, Rekeland IG, Sapkota D, Kristoffersen EK, Sorland K, Bruland O, Dahl O, et al. B-Lymphocyte depletion in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. An open-label phase II study with rituximab maintenance treatment. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129898.

CDC. Treatment of ME/CFS. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/treatment/index.html. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Clark HD, Wells GA, Huet C, McAlister FA, Salmi LR, Fergusson D, et al. Assessing the qulality of randomized trials: reliability of the Jadad scale. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:448–52.

Nilsson MKL, Zachrisson O, Gottfries CG, Matousek M, Peilot B, Forsmark S, Schuit RC, Carlsson ML, Kloberg A, Carlsson A. A randomised controlled trial of the monoaminergic stabiliser (-)-OSU6162 in treatment of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018;30(3):148–57.

Arnold LM, Blom TJ, Welge JA, Mariutto E, Heller A. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial of duloxetine in the treatment of general fatigue in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(3):242–53.

Sulheim D, Fagermoen E, Winger A, Andersen AM, Godang K, Müller F, Rowe PC, Saul JP, Skovlund E, Øie MG, Wyller VB. Disease mechanisms and clonidine treatment in adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome: a combined cross-sectional and randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):351–60.

Blockmans D, Persoons P, Van Houdenhove B, Bobbaers H. Does methylphenidate reduce the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome? Am J Med. 2006;119(2):167.e23–30.

Blacker CV, Greenwood DT, Wesnes KA, Wilson R, Woodward C, Howe I, Ali T. Effect of galantamine hydrobromide in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(10):1195–204.

Hickie IB, Wilson AJ, Wright JM, Bennett BK, Wakefield D, Lloyd AR. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of moclobemide in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(9):643–8.

Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Zitman FG, Vreden SG, Hoofs MP, Fennis JF, Galama JM, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 1996;347(9005):858–61.

Snorrason E, Geirsson A, Stefansson K. Trial of a Selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, galanthamine hydrobromide, in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 1996;2(2–3):35–54.

McDermott C, Richards SC, Thomas PW, Montgomery J, Lewith G. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized controlled trial of a natural killer cell stimulant (BioBran MGN-3) in chronic fatigue syndrome. QJM. 2006;99(7):461–8.

Zachrisson O, Regland B, Jahreskog M, Jonsson M, Kron M, Gottfries CG. Treatment with staphylococcus toxoid in fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome—a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2002;6(6):455–66.

Rowe KS. Double-blind randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of intravenous gamma globulin for the management of chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31(1):133–47.

Strayer DR, Carter WA, Brodsky I, Cheney P, Peterson D, Salvato P, Thompson C, Loveless M, Shapiro DE, Elsasser W, et al. A controlled clinical trial with a specifically configured RNA drug, poly(I).poly(C12U), in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(Suppl 1):S88–95.

Blockmans D, Persoons P, Van Houdenhove B, Lejeune M, Bobbaers H. Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Am J Med. 2003;114(9):736–41.

Rowe PC, Calkins H, DeBusk K, McKenzie R, Anand R, Sharma G, Cuccherini BA, Soto N, Hohman P, Snader S, Lucas KE, Wolff M, Straus SE. Fludrocortisone acetate to treat neurally mediated hypotension in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(1):52–9.

Cleare AJ, Heap E, Malhi GS, Wessely S, O’Keane V, Miell J. Low-dose hydrocortisone in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised crossover trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9151):455–8.

McKenzie R, O’Fallon A, Dale J, Demitrack M, Sharma G, Deloria M, Garcia-Borreguero D, Blackwelder W, Straus SE. Low-dose hydrocortisone for treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(12):1061–6.

Peterson PK, Pheley A, Schroeppel J, Schenck C, Marshall P, Kind A, Haugland JM, Lambrecht LJ, Swan S, Goldsmith S. A preliminary placebo-controlled crossover trial of fludrocortisone for chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(8):908–14.

Montoya JG, Anderson JN, Adolphs DL, Bateman L, Klimas N, Levine SM, Garvert D, Kaiser JD. KPAX002 as a treatment for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a prospective, randomized trial. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(3):2890–900.

Castro-Marrero J, Cordero MD, Segundo MJ, Sáez-Francàs N, Calvo N, Román-Malo L, Aliste L, de Fernández Sevilla T, Alegre J. Does oral coenzyme Q10 plus NADH supplementation improve fatigue and biochemical parameters in chronic fatigue syndrome? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22(8):679–85.

Forsyth LM, Preuss HG, MacDowell AL, Chiazze L Jr, Birkmayer GD, Bellanti JA. Therapeutic effects of oral NADH on the symptoms of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82(2):185–91.

Bleijenberg G, Van der Meer JW. The effect of acclydine in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled Trial. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2(5):e19.

Brouwers FM, Van Der Werf S, Bleijenberg G, Van Der Zee L, Van Der Meer JW. The effect of a polynutrient supplement on fatigue and physical activity of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. QJM. 2002;95(10):677–83.

Roerink ME, Bredie SJH, Heijnen M, Dinarello CA, Knoop H, Van der Meer JWM. Cytokine inhibition in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(8):557–64.

The GK, Bleijenberg G, Buitelaar JK, van der Meer JW. The effect of ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):528–33.

Weatherley-Jones E, Nicholl JP, Thomas KJ, Parry GJ, McKendrick MW, Green ST, Stanley PJ, Lynch SP. A randomised, controlled, triple-blind trial of the efficacy of homeopathic treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(2):189–97.

Janse A, Worm-Smeitink M, Bleijenberg G, Donders R, Knoop H. Efficacy of web-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(2):112–8.

Wiborg JF, van Bussel J, van Dijk A, Bleijenberg G, Knoop H. Randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy delivered in groups of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(6):368–76.

Vos-Vromans DC, Smeets RJ, Huijnen IP, Köke AJ, Hitters WM, Rijnders LJ, Pont M, Winkens B, Knottnerus JA. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment versus cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Intern Med. 2016;279(3):268–82.

Nijhof SL, Bleijenberg G, Uiterwaal CS, Kimpen JL, van de Putte EM. Effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome (FITNET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1412–8.

Núñez M, Fernández-Solà J, Nuñez E, Fernández-Huerta JM, Godás-Sieso T, Gomez-Gil E. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: group cognitive behavioural therapy and graded exercise versus usual treatment. A randomised controlled trial with 1 year of follow-up. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(3):381–9.

White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, Potts L, Walwyn R, DeCesare JC, Baber HL, Burgess M, Clark LV, Cox DL, Bavinton J, Angus BJ, Murphy G, Murphy M, O'Dowd H, Wilks D, McCrone P, Chalder T, Sharpe M. PACE trial management group. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):823–36.

Chalder T, Deary V, Husain K, Walwyn R. Family-focused cognitive behaviour therapy versus psycho-education for chronic fatigue syndrome in 11- to 18-year-olds: a randomized controlled treatment trial. Psychol Med. 2010;40(8):1269-79.

O’Dowd H, Gladwell P, Rogers CA, Hollinghurst S, Gregory A. Cognitive behavioural therapy in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled trial of an outpatient group programme. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(37):1–121.

Stulemeijer M, de Jong LW, Fiselier TJ, Hoogveld SW, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7481):14.

Prins JB, Bleijenberg G, Bazelmans E, Elving LD, de Boo TM, Severens JL, van der Wilt GJ, Spinhoven P, van der Meer JW. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9259):841–7.

Deale A, Chalder T, Marks I, Wessely S. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(3):408–14.

Sharpe M, Hawton K, Simkin S, Surawy C, Hackmann A, Klimes I, Peto T, Warrell D, Seagroatt V. Cognitive behaviour therapy for the chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312(7022):22–6.

Clark LV, Pesola F, Thomas JM, Vergara-Williamson M, Beynon M, White PD. Guided graded exercise self-help plus specialist medical care versus specialist medical care alone for chronic fatigue syndrome (GETSET): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):363–73.

Ho RT, Chan JS, Wang CW, Lau BW, So KF, Yuen LP, Sham JS, Chan CL. A randomized controlled trial of qigong exercise on fatigue symptoms, functioning, and telomerase activity in persons with chronic fatigue or chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44(2):160–70.

Moss-Morris R, Sharon C, Tobin R, Baldi JC. A randomized controlled graded exercise trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: outcomes and mechanisms of change. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(2):245–59.

Powell P, Bentall RP, Nye FJ, Edwards RH. Randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):387–90.

Fulcher KY, White PD. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1997;314(7095):1647–52.

Friedberg F, Adamowicz J, Caikauskaite I, Seva V, Napoli A. Efficacy of two delivery modes of behavioral self management in severe chronic fatigue syndrome. Fatigue Biomed Health Behav. 2016;4(3):158–74.

Pinxsterhuis I, Sandvik L, Strand EB, Bautz-Holter E, Sveen U. Effectiveness of a group-based self-management program for people with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(1):93–103.

Tummers M, Knoop H, van Dam A, Bleijenberg G. Implementing a minimal intervention for chronic fatigue syndrome in a mental health centre: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42(10):2205–15.

Tummers M, Knoop H, Bleijenberg G. Effectiveness of stepped care for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized non-inferiority trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(5):724–31.

Knoop H, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Guided self-instructions for people with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):340–1.

Wearden AJ, Dowrick C, Chew-Graham C, Bentall RP, Morriss RK, Peters S, Riste L, Richardson G, Lovell K, Dunn G, Fatigue Intervention by Nurses Evaluation (FINE) trial writing group and the FINE trial group. Nurse led, home based self help treatment for patients in primary care with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1777.

Taylor RR. Quality of life and symptom severity for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: findings from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(1):35–43.

Kim JE, Seo BK, Choi JB, Kim HJ, Kim TH, Lee MH, Kang KW, Kim JH, Shin KM, Lee S, Jung SY, Kim AR, Shin MS, Jung HJ, Park HJ, Kim SP, Baek YH, Hong KE, Choi SM. Acupuncture for chronic fatigue syndrome and idiopathic chronic fatigue: a multicenter, non-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:314.

Ng SM, Yiu YM. Acupuncture for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized, sham-controlled trial with single-blinded design. Altern Ther Health Med. 2013;19(4):21–6.

Huanan L, Jingui W, Wei Z, Na Z, Xinhua H, Shiquan S, Qing S, Yihao H, Runchen Z, Fei M. Chronic fatigue syndrome treated by the traditional Chinese procedure abdominal tuina: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37(6):819–26.

Hobday RA, Thomas S, O’Donovan A, Murphy M, Pinching AJ. Dietary intervention in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21(2):141–9.

Walach H, Bosch H, Lewith G, Naumann J, Schwarzer B, Falk S, Kohls N, Haraldsson E, Wiesendanger H, Nordmann A, Tomasson H, Prescott P, Bucher HC. Effectiveness of distant healing for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled partially blinded trial (EUHEALS). Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(3):158–66.

Deale A, Chalder T, Wessely S. Commentary on: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:491–2.

Lloyd AR, Hickie I, Brockman A, Hickie C, Wilson A, Dwyer J, Wakefield D. Immunologic and psychologic therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1993;94(2):197–203.

Maxmen A. A reboot for chronic fatigue syndrome research. Nature. 2018;553(7686):14–7.

Cleare AJ, Reid S, Chalder T, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015;2015:1101.

Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC, Li K, Bright AT, Alaynick WA, Wang L, Baxter A, Nathan N, Anderson W, Gordon E. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(37):E5472–80.

Collatz A, Johnston SC, Staines DR, Marshall-Gradisnik SM. A systematic review of drug therapies for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Clin Ther. 2016;38(6):1263–71.

Farrar DJ, Locke SE, Kantrowitz FG. Chronic fatigue syndrome. 1: etiology and pathogenesis. Behav Med. 1995;21(1):5–16.

Chambers D, Bagnall AM, Hempel S, Forbes C. Interventions for the treatment, management and rehabilitation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an updated systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(10):506–20.

Reid S, Chalder T, Cleare A, Hotopf M, Wessely SBMJ. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Evid. 2011;2011:1101.

Castro-Marrero J, Sáez-Francàs N, Santillo D, Alegre J. Treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: all roads lead to Rome. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(5):345–69.

CDC. Cormobid conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/diagnosis/comorbid-conditions.html. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Cella M, White PD, Sharpe M, Chalder T. Cognitions, behaviours and co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):375–80.

Weaver SA, Janal MN, Aktan N, Ottenweller JE, Natelson BH. Sex differences in plasma prolactin response to tryptophan in chronic fatigue syndrome patients with and without comorbid fibromyalgia. J Women’s Health. 2010;19(5):951–8.

Fakhoury M. Revisiting the serotonin hypothesis: implications for major depressive disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(5):2778–86.

Myhill S, Booth NE, McLaren-Howard J. Chronic fatigue syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2009;2:1–16.

Driessen E, Hollon SD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for mood disorders: efficacy, moderators and mediators. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;33(3):537–55.

Otte C. Cognitive behavioral therapy in anxiety disorders: current state of the evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(4):413–21.

Matusiewicz AK, Hopwood CJ, Banducci AN, Lejuez CW. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;33(3):657–85.

Gutiérrez M, Sánchez M, Trujillo A, Sánchez L. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic psychosis. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria. 2009;37(2):106–14.

Larun L, Brurberg KG, Odgaard-Jensen J, Price JR. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:CD003200.

Bjørkum T, Wang CE, Waterloo K. Patients’ experience with treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129(12):1214–6.

Twisk FN, Maes M. A review on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): CBT/GET is not only ineffective and not evidence-based, but also potentially harmful for many patients with ME/CFS. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30(3):284–99.

Zhang Q, Gong J, Dong H, Xu S, Wang W, Huang G. Acupuncture for chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2019;37(4):211–22.

Goldsmith LP, Dunn G, Bentall RP, Lewis SW, Wearden AJ. Therapist effects and the impact of early therapeutic alliance on symptomatic outcome in chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144623.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Oriental Medicine R&D Project (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03025221).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D-YK (mainly) and S-JK (partially) searched the literatures. D-YK extracted and analyzed the data. J-SL and S-YP participated in discussion. D-YK and C-GS wrote the manuscript. C-GS had supervised the whole process of this study with initial design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the authors noted that one study (PACE trial) had been missed in the captured data. Accordingly, some corrections were made in multiple sections, including the addition of the reference information for the PACE trial in the reference list.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, DY., Lee, JS., Park, SY. et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). J Transl Med 18, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-02196-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-02196-9