Abstract

Background

Catastrophic health expenditures (CHE) are of concern to policy makers and can prevent individuals accessing effective health care services. The exposure of households to CHE is one of the indices used to evaluate and address the level of financial risk protection in health systems, which is a key priority in the global health policy agenda and an indicator of progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goal for Universal Health Coverage. This study aims to assess the CHE at population and disease levels and its influencing factors in Iran.

Methods

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis. The following keywords and their Persian equivalents were used for the review: Catastrophic Health Expenditures; Health Equity; Health System Equity; Financial Contribution; Health Expenditures; Financial Protection; Financial Catastrophe; and Health Financing Equity. These keywords were searched with no time limit until October 2019 in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Embase, and the national databases of Iran. Studies that met a set of inclusion criteria formed part of the meta-analysis and results were analyzed using a random-effects model.

Results

The review identified 53 relevant studies, of which 40 are conducted at the population level and 13 are disease specific. At the population level, the rate of CHE is 4.7% (95% CI 4.1% to 5.3%, n = 52). Across diseases, the percentage of CHE is 25.3% (95% CI 11.7% to 46.5%, n = 13), among cancer patients, while people undergoing dialysis face the highest percentage of CHE (54.5%). The most important factors influencing the rate of CHE in these studies are health insurance status, having a household member aged 60–65 years or older, gender of the head of household, and the use of inpatient and outpatient services.

Conclusion

The results suggest that catastrophic health spending in Iran has increased from 2001 to 2015 and has reached its highest levels in the last 5 years. It is therefore imperative to review and develop fair health financing policies to protect people against financial hardship. This review and meta-analysis provides evidence to help inform effective health financing strategies and policies to prioritise high-burden disease groups and address the determinants of CHE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare is a natural right of every human being that is necessary in all the stages of life and must not be affected by their wealth or income [1, 2]. Presently, the rising costs of healthcare services and their impact on the economy have become major concerns for health policy makers [3,4,5,6]. Health systems are therefore seeking financing mechanisms that will improve access to quality health services in underserved communities [7, 8]. The reliance on out-of-pocket expenditure to finance health services is a common feature in many low- and middle-income countries. Households without adequate financial protection face the risk of incurring large unanticipated medical expenditures. These unforeseen expenditures may lead to indebtedness, a reduction in living standards, and ultimately impoverishment [9, 10].

Improving financial protection to minimize the extent to which households incur catastrophic health expenditures (CHE) and are pushed into poverty due to high medical spending has received substantial attention. The link between poverty and health is well established, and in 2015 CHE was included as a key indicator to monitor progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) for Universal Health Coverage. More recently, health insurance has been put forward as an instrument to provide financial protection and to achieve universal coverage [1, 3, 7]. As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) has underlined the importance of protections against CHE and considers fair financing to be a key objective for health systems. Fair health financing ensures that households do not pay beyond a certain proportion of their total income for health out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) and protects them against impoverishment due to CHE [10].

CHE can occur in all countries at all stages of development. The CHE rate is one of the main factors used to calculate fairness in health financing [11, 12]. Health expenditures are considered catastrophic when they exceed a certain amount (e.g. 10%) in relation to the household’s income, expenditure, or the ability to pay [12, 13]. CHE can either be a proportion of total income/consumption (e.g. 10%) or the ability to pay. Ability to pay is defined as the capability to use money for health expenditure with respect to annual household income that is not required for subsistence, for example household income less spending on food or housing. Health expenditure not exceeding 5% of annual household income is a common benchmark of ability to pay [14]. This is because there is starting to be a movement away from ability-to-pay (i.e. non-food expenditure as a denominator). For example, the 10% threshold is used for the UN SDGs indicator and for UHC progress tracking by the World Bank and WHO [15].

CHE can lead to a reduction in consumption in the short-term and the use of savings, sale of assets, and borrowing in the long-term, thus reducing the household’s living standards [16]. Globally, more than 150 million people are exposed to CHE annually, and around 100 million are pushed into poverty because of OOPs [17]. Various studies have been conducted on CHE in Iran at the population level and across diseases, and rates of CHE ranging between 2.5 and 72.5% have been reported [17,18,19].

The purpose of the present research was to systematically review the studies investigating CHE in Iran and to synthesize their results across populations, diseases, and vulnerable groups, thus providing new insights into CHE in Iran as an indicator of fair health financing.

Methodology

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies carried out on CHE in Iran based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20]. All the different phases of the review, from the search to quality assessment of the studies, were independently performed by two reviewers and disagreements were examined by a third reviewer. Studies were accessed from a number of Persian and English language databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Embase, MagIran, IranMedex, SID, and IranDoc as well as Google Scholar. In addition, the bibliographies of selected studies were searched to identify additional studies. All studies conducted up to October 2019 were included. The following keywords and their Persian equivalents were used to search the databases: Catastrophic Health Expenditures; Health Equity; Health System Equity; Financial Contribution; Health Expenditures; Financial Protection; Financial Catastrophe; and Health Financing Equity. The operators “And” and “Or” were also used to broaden the search. A detailed search strategy is included in Additional file 1.

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies

The inclusion criteria were: (1) any primary study in English or Persian measuring and reporting catastrophic health expenditures, and/or factors affecting them across demographics and diseases, and (2) studies conducted in Iran.

Types of participants

The participants are households or patients who lived in Iran.

Types of intervention

Factors that influence the catastrophic health expenditure of households.

Types of outcomes

Catastrophic health expenditure: Payment is considered catastrophic when a household has to cut its basic living expenses over 1 year in order to afford the medical expenses of its household member(s).

Exclusion criteria

Methodological studies and studies that do not measure or report CHE and using approches other than CHE to measure equity in health financing were excluded.

Quality assessment

To assess the quality of the studies, first the name of the journals and authors were concealed. The studies were then given to two members of the research team to independently examine the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a third researcher resolving the disagreements. As the majority of the studies included in this review are observational, the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [21] was used in quality assessment. This checklist consists of five main domains (title and abstract, introduction, results, discussion and other information) and 22 sections, with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 44. Checklist items were rated on a three-point scale (yes = 2, cannot tell = 1, and no = 0). Studies were divided into three groups: (1) high quality (a score higher than 30) (2) moderate quality (a score between 16 and 30), and (3) low quality (a score less than 16). Studies with quality scores higher than 16 were included in the meta-analysis stage.

Data extraction

The general characteristics of the studies were extracted and presented in a data extraction form. This form included first author’s name, year of publication, study design, data collection period, location/region, sample size, data collection method, and catastrophic health spending rate as well as factors affecting it.

Statistical analysis

Study heterogeneity was investigated using Cochran’s Q and \(I^{2}\) index. An I2 > 50% or a P-value for the Q test < 0.10 indicates significant heterogeneity [22]. Since the results of Q test and \(I^{2}\) index indicated significant heterogeneity between the studies, a random effects model was used for meta-analysis and synthesized results were obtained from the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software, version 3. Factors affecting the rate of CHE were extracted and classified by population and disease. The possibility of publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of a funnel plot.

Results

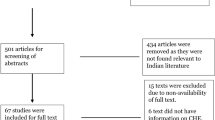

A systematic search of the keywords identified 360 studies in the selected databases. An additional 12 studies were also obtained though manual searches of the bibliographies of the final studies (Fig. 1). In total, 52 papers [1, 3, 11, 12, 18, 19, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] were included in the meta-analysis stage (Figs. 1, 2). These studies were classified into two groups, based on whether they investigate CHE across demographics (40 studies) or diseases (13 studies). The general characteristics of the studies and the data extracted from them are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Analysis of publication bias revealed that no publication bias was identified by Egger’s line regression test (P > 0.05). A visual inspection of the symmetry graphic in the funnel plot indicated no evidence of publication bias or small-study effects (Fig. 3).

CHE at population level

The rate of CHE in the studies conducted at the population level is estimated to be 4.7%, ranging from 4.1 to 5.3% at 95% Confidence Interval-CI (Table 3). The pooled estimate of CHE prevalence in Iran are shown in by the forrest plot (Fig. 3). The following results are reported with threshold level of 40% of income. The lowest percentage of CHE is reported by Homaie-Rad et al. among 6307 Iranian retirees (0.6%) [41], while the highest percentage of CHE rate is reported by Asefzadeh et al. among 100 households in Qazvin Province (24%) [26].

The studies conducted at the population level use either primary data or secondary data. A subgroup analysis was therefore performed based on the type of data used in these studies. Cochran’s Q test and \(I^{2}\) index indicated a significant heterogeneity between the results of studies using primary data and those using secondary data (Table 4). The percentage of CHE reported in studies that use primary data is 11.6%, which varies between 10.4 and 13%. On the other hand, the percentage of CHE estimated in studies that use secondary data is 3%, and ranges between 2.3 and 4%.

To determine the trend of CHE rates in Iran, the studies were divided into four groups based on the timeline of the studies; from 1984 to 2017. The highest percentage of CHE is observed in 2011–2017 (6.9%), while the lowest percentage of CHE is observed in 2001–2005 (4.1%) (Table 5).

Factors that affect CHE at the population level

Factors that affect CHE at the population level include health insurance status; supplementary insurance status; living in rural area; age, gender, employment status and education level of the head of household; having a household member aged 60–65 years or older; number of members aged 12 years or below; number of members aged 5 years or below; having a household member with chronic illness or disabled or required care; number of working household members; marital status; and household size. The economic status of households; household expenditures; wealth index; income per capita; informal payments; expenditure per capita; and gross income by income decile groups are the economic factors reported as determinants of CHE rates (Table 6).

The use of inpatient services, dental care, outpatient services, rehabilitation, drug rehabilitation, medical and diagnostic services, the frequency of receiving of healthcare services, and drug prices are other factors that affect CHE. Each of these factors can have an powerful impact on the level of CHE. Factors affecting levels of CHE must be considered and understood before allocating budgets for health. Identifying theses factors guarantee access to professionals, technologies, and necessary supplies for the promotion and recovery of their health as well as disease prevention. Health insurance status is the only variable, whose effect on facing CHE was examined in all studies. Most of the studies indicated that having health insurance reduced CHE.

CHE at the diseases level

Due to the high heterogeneity of the studies (Q value = 544.516, df = 12, P < 0.001, I2 = 97.72), a random effects model was used to synthesize the results. The percentage of CHE at diseases level is 25.3%, ranging from 11.7 to 46.5% at the 95% CI (Table 7). The following results are reported with threshold level of 40% of income. The highest percentage of CHE is observed among patients undergoing dialysis (72.5%) [64], while the lowest percentage of CHE is observed among multiple sclerosis (MS) patients (3.4%) [42]. Studies were divided into groups based on disease type, and the level of CHE for each group is presented in Table 8. The highest percentage of CHE (54.5%) is observed among cancer patients (33.2–74.4% at the 95% CI) and the lowest level of CHE (9.1%) is observed among MS patients (3.2–23% at 95% CI). The pooled estimate of CHE prevalence based on the diseases level are shown in Fig. 4.

Factors affecting CHE at the disease level

Factors affecting CHE rate at the disease level were categorized into three groups: (a) socio-demographic factors, (b) economic factors and (c) disease-related factors. Socio-demographic factors included: gender of the head of household, basic insurance status and insurance type, supplementary insurance status, being native, having a household member older than 60 years old, employment status of the head of household, having a household members with illness, having members with special diseases, having members with chronic diseases, having members aged 12 years or below, having members that are disabled or require care, education level of the patient, education level of the head of the household, household size, age of the head of household, having a member aged 6 years or below, having a member aged 14 years old or below, marital status of the head of household, age and gender of the patient, having a member aged 40–59 years old, access to clean water, distance between the place of residence and health centers, and living in a rural areas. Economic factors included: income, wealth index, property ownership, economic status, OOPs, and having specific resources for paying healthcare costs. Disease-related factors included: frequency of using inpatient services, hospitalization days, admission to private hospitals, frequency of using outpatient services, use of rehabilitation services and dental care, drug brands, avoiding healthcare services due to financial problems, type of treatment in cancer patients (e.g. chemotherapy), and dialysis frequency.

Discussion

The overall percentage of CHE in Iran is estimated to be 4.7% based on the synthesis of the reviewed studies. Further analysis reveals that the percentage of CHE is 11.6% in studies that use primary data and 3% in studies that use secondary data. Studies with primary data use the WHO survey and interviews for data collection, while those with secondary data use data from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) which is collected regularly by the Iran Statistics Center (ISC). The 8.6% difference is likely due to differences in sample size and the instruments used to collect data. Evidence shows that questionnaires that are designed based on the WHO survey more accurately measure the health expenditures of households compared with HIES survey, since the former is specifically designed to measure health expenditures [39, 65, 66]. A systematic review conducted by Ghorbanian et al. in 2015 revealed that studies that use the WHO survey for data collection report higher levels of CHE than studies that use the HIES survey. Their review estimates levels of CHE at 3.91% at the population level [39], which is lower than the value estimated in this paper. A likely reason for this inconsistency is the higher number of studies that use primary data included in this study compared with the Ghorbanian et al. review. In another study of levels of CHE across Iran’s provinces over a 7-year period (2008–2014), the highest percentage of CHE (5.2%) is observed in Fars Province and the lowest percentage of CHE (0.7%) is observed in South Khorasan Province [60].

In this review, the identified studies were divided into four groups based on the timeline of the studies (1984–2015). The results show that the number of studies on CHE has increased during this period, reaching its highest level between 2011 and 2015. Moreover, it is revealed that the level of CHE increased from 2001 to 2015, with the highest percentage of CHE observed between 2011 and 2015. Despite the policies developed and actions taken to reduce OOPs, levels of CHE are still high and have reached their highest levels in recent years. This is mainly caused by the increasing costs of healthcare, which includes the cost of medications and use of complex treatments that require specialized facilities and equipment. This creates financial difficulties for households and puts pressure on the strained health budgets of different countries [67]. Another reason for rising CHE rates is the financing mechanisms used in various health systems. In under-developed and low-income countries, OOPs consistute a substantial proportion of health financing and adequate prepayment mechanisms are often lacking [15].

At the level of diseases, the percentage of CHE is estimated to be 25.3%. The highest level of CHE is observed among cancer patients (54.5%) and the lowest among MS patients (9.1%). In a study by Kavoosi and colleagues on CHE in a southern Iranian city, CHE rate is reported to be 67.9% among cancer patients [12]. Other studies have shown that households with cancer patients have the highest levels of catastrophic health spending [12, 68]. It is therefore critical to review the existing financing policies regarding these patients and to develop fair health financing strategies for these vulnerable groups in Iran.

Cancer patients in other countries are facing catastrophic health spending as well due to the high costs of treatment. A 2014 study in India reports 53% of patients with non-communicable diseases are exposed to CHE, with cancer patients experiencing the highest percentage of CHE (74%) [69]. In another study, which was conducted in 2017 in Malaysia on colorectal cancer patients, the authors find that 47.8% of patients’ families experience CHE [27]. In addition, a study across eight Southeast Asian countries reports that 31% of cancer patients experience financial catastrophe [70]. In South Korea, Lee and colleagues show that CHE in the households without disabled members was 27.6%, 13.2%, 7.8%, and 5.1% with the threshold at 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% respectively. Factors associated with incidence of CHE included the number of household members, household income, receiving public assistance, having a member over 65 years and household head’s employment status [71]. A study by Ma and colleagues finds that the incidence of catastrophic expenditure in China experienced a 0.70-fold change between 2010 (12.57%) and 2016 (8.94%). One of the most important factors affecting CHE is household income [72]. In Kimani’s study in Kenya, among those who utilize health care, 11.7% experience CHE and 4% are impoverished by health care payments [73].

Among the social factors that affect levels of CHE at the population level, health insurance status (reported in 13 studies) and employment of the head of household (reported in 8 studies) are the most important factors that reduce levels of CHE. Having a member aged 60–65 years or older in the household (reported in 12 studies) is the most important factor that increases levels of CHE. Households that have no health insurance coverage or use services that are not covered in an insurance plan have to spend a higher portion of their income and possibly sell assets to purchase health services. Risk pooling and proper prepayment mechanisms provided by insurance companies can therefore play a significant role in protecting people against CHE and ensure their access to healthcare [15, 74,75,76,77,78]. However, a study conducted in China shows that health insurance coverage can increase levels of CHE, since people with health insurance can be encouraged to use more health services [79]. Employment status of the household head is another major factor that affects levels of CHE and can reduce the likelihood of experiencing financial hardship by increasing the financial capacity of the household [13, 80]. Older individuals are more susceptible to various diseases and are more in need of healthcare. Having older individuals in the household therefore increases its health expenditures and, consequently, increases its chance of experiencing CHE [8]. In a number of other studies conducted in different countries, the presence of an older individual has been shown to increase the risk of incurring CHE [7, 78, 81,82,83,84,85].

Among economic factors, the economic status and wealth index of households are the most important factors in decreasing levels of CHE, while high household expenditure is the most important factor in increasing levels of CHE. Better economic status and higher wealth index indicate that the household has more resources and a higher payment capacity; thus, higher wealth index is associated with lower risk of incurring CHE [17, 63]. Other studies conducted in India [80], Mexico [82], Turkey [7], Vietnam [85], and Burkina Faso [86] have also reported the economic status of households as a key determinant of CHE. In disease-related factors, the frequency of using inpatient services, outpatient services, and dental care are the most important factors affecting levels of CHE. This is in line with the findings from studies conducted in other settings, which indicate that the risk of incurring CHE increases with the frequency of using inpatient [86,87,88] and outpatient care [84].

At the disease level, the gender of the head of household, basic insurance status, supplementary insurance status, and being native are four major social determinants of CHE. Female heads of households have less job opportunities and a lower chance of employment, and they are mostly supported by their children or relatives, charities, and retirement pensions. As a result, female headed households are more likely to incur CHE [76, 84]. The farther the distance from the place of residence to health centers, the higher the direct non-medical costs of the households (e.g. transportation and accommodation costs) [13]. Non-native households are therefore more likely to incur CHE [12, 75]. Similarly to the population level, income and wealth index (reported in 5 and 4 studies respectively) are the most important economic factors that reduce the likelihood of patients’ households incurring CHE. Among disease-related factors, the frequency of using inpatient services, hospitalization days, admission to private hospitals, and the frequency of using outpatient services are the most important factors and are positively associated with the likelihood of patients’ households being exposed to CHE [12, 36, 38, 40, 42, 52]. Studies in different settings have shown that increased usage of healthcare services is associated with a higher risk of incurring CHE [86].

Conclusions and recommendations

The present review provides a comprehensive picture of fairness in Iran’s health system in terms of addressing CHE. The results demonstrate the high percentage of households exposed to CHE in Iran. This rate is significantly higher in vulnerable groups and in households with certain diseases. Fore some diseases, studies show that more than half of patients incur CHE. Therefore, it is critical to review existing health financing policies and to develop new policies to protect people against financial hardship. Designing a health financing system that protects demographics and diseases with greater exposure to CHE can contribute to health equity and significantly reduce levels of CHE.

Countries can reduce involved in illness by relying more on prepayment and less on OOPs. In that way, people contribute to funding health services in a predictable fashion, and are not required to suddenly find money to pay for services when they fall ill unexpectedly. Catastrophic expenditures do not automatically disappear with rising income. National health financing systems must be designed not only to allow people to access services when they are needed, but also to protect households from financial catastrophe, by reducing out-of-pocket spending. In the long term, the aim should be to develop mandatory prepayment mechanisms, such as social health insurance, tax-based financing, or some mix of prepayment mechanisms. In moving towards such a system, flexible short-term responses will be needed, which will depend on the stage of economic development of the country and on the social and political context. Policy-makers will need to consider how to expand population coverage through prepayment mechanisms; protect the poor and disadvantaged; design a benefits package; and decide the level of cost sharing by the patients.

Availability of data and materials

No additional data available.

References

Arab M, Roodbari M, Rezapoor A. Catastrophic and impoverishing health expenditure in Tehran urban population. J Health Admin. 2016;19(63):55–67.

Jakovljevic M, Timofeyev Y, Ekkert NV, Fedorova JV, Skvirskaya G, Bolevich S, et al. The impact of health expenditures on public health in BRICS nations. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(6):516.

Moghadam MN, Banshi M, Javar MA, Amiresmaili M, Ganjavi S. Iranian household financial protection against catastrophic health care expenditures. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(9):62.

Grima S, Spiteri JV, Jakovljevic M, Camilleri C. High out-of-pocket health spending in countries with a mediterranean connection. Front Public Health. 2018;6:145.

Jakovljevic MB. BRIC’s growing share of global health spending and their diverging pathways. Front Public Health. 2015;3:135.

Jakovljevic M, Camilleri C, Rancic N, Grima S, Jurisevic M, Grech K, et al. Cold war legacy in public and private health spending in Europe. Front Public Health. 2018;6:215.

Yardim MS, Cilingiroglu N, Yardim N. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Turkey. Health Policy. 2010;94(1):26–33.

Chang AY, Cowling K, Micah AE, Chapin A, Chen CS, Ikilezi G, et al. Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2233–60.

Sachs JD. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2206–11.

Wagstaff A. Measuring financial protection in health: The World Bank; 2008.

Abolhallaje M, Hasani S, Bastani P, Ramezanian M, Kazemian M. Determinants of catastrophic health expenditure in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):155.

Kavosi Z, Delavari H, Keshtkaran A, Setoudehzadeh F. Catastrophic health expenditures and coping strategies in households with cancer patients in Shiraz Namazi hospital. 2014.

Ekman B. Catastrophic health payments and health insurance: some counterintuitive evidence from one low-income country. Health Policy. 2007;83(2–3):304–13.

Gartoulla P, Liabsuetrakul T, Chongsuvivatwong V, McNeil E. Ability to pay and impoverishment among women who give birth at a University Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(10):1145–56.

Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff. 2007;26(4):972–83.

Van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Garg CC, et al. Catastrophic payments for health care in Asia. Health Econ. 2007;16(11):1159–84.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kadama P, Nabyonga J, Ogwal PO, Nabukhonzo P, et al. Understanding the impact of eliminating user fees: utilization and catastrophic health expenditures in Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):866–76.

Ghoddoosinejad J, Jannati A, Gholipour K, Baghestan EB. Households encountering with catastrophic health expenditures in Ferdows, Iran. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2014;89(2):81–4.

Nekoeimoghadam M, Akbari-Javar M, Amiresmaili M, Baneshi M, Ganjavai S. Households exposure to catastrophic health expenditures and the affecting factors in Kerman Province, Iran. J Manag Med Inform Sch. 2013;1(2):101–90.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Vandenbroucke JP, Von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Aeenparast Rezaei, Zandian Haeri-Mehrizi. Catastrophic health expenditures in Iran: a review of the literature. Payesh. 2016;15(1):7–17.

Alizadeh H, Mohammad H, Fazaeli A. Status of justice in financing the health system in Iran. Int J Soc Welf. 2005;5(19):279–300.

Amery H, Jafari A, Panahi M. Determining the rate of catastrophic health expenditure and its influential factors on families in Yazd Province. J Health Admin. 2013;16(52):51–60.

Asefzadeh S, Alijanzadeh M, Gholamalipoor S, Farzaneh A. Households encountering with catastrophic health expenditures in Qazvin, Iran. Health Inf Manag. 2013;10(1):1–8.

Azzani M, Yahya A, Roslani AC, Su TT. Catastrophic health expenditure among colorectal cancer patients and families: a case of Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2017;29(6):485–94.

Daneshkohan A, Karami M, Najafi F, Matin BK. Household catastrophic health expenditure. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40(1):94.

Davari M, Kheyri M, Nourbakhsh SMK, Khadivi R. Socioeconomic status and catastrophic health expenditure evaluation in IR Iran: a comparative study in 2004 and 2011. Soc Determin Health. 2015;1(2):48–59.

Davari M, Moafi A, Yarmohammadian MH, Haghighi EK. The direct medical costs of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in children in Isfahan province. J Health Inf Manag. 2015;11(7):1045–57.

Fazaeli AA, Ghaderi H, Fazaeli AA, Lotfi F, Salehi M, Mehrara M. Main determinants of catastrophic health expenditures: a Bayesian logit approach on Iranian household survey data (2010). Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(4):335.

Fazaeli AA, Seyedin H, Moghaddam AV, Delavari A, Salimzadeh H, Varmazyar H, et al. Fairness of financial contribution in Iranian health system: trend analysis of national household income and expenditure, 2003–2010. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(5):260.

Ghafoori MH, Ebadifard AF, Arab M, Mahmoodi M, Yusef ZN, Rezapour A. The distribution of health expenditures in Tehran’s districts. 2014.

Ghiasi A, Baghi A, Rezapour A, Alipour V, Ahadinezhad B, Mahmoudi M, et al. Health insurance, medicine expenses and catastrophic health expenditures. J Health Admin. 2016;18(62):64–74.

Ghiasvand H, Gorji HA, Maleki M, Hadian M. Catastrophic health expenditure among Iranian rural and urban households, 2013–2014. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(9):1–12.

Ghiasvand H, Hadian M, Maleki M, Shabaninejad H. Determinants of catastrophic medical payments in hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences 2009. Hakim Res J. 2010;13(3):145–54.

Ghiasvand H, Hadian M, Maleki MR. Relationship between health insurance and catastrophic medical payment in hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Science; 2009. 2011.

Ghiasvand H, Sha’baninejad H, Arab M, Rashidian A. Hospitalization and catastrophic medical payment: evidence from hospitals located in Tehran. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(7):507–13.

Ghorbanian A, Rashidian A, Lankarani KB, Kavosi Z. The prevalence and determinants of catastrophic health expenditures in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Scope. 2019;8(1):1–16.

Hajizadeh M, Nghiem HS. Out-of-pocket expenditures for hospital care in Iran: who is at risk of incurring catastrophic payments? Int J Health Care Financ Econ. 2011;11(4):267.

Homaie Rad E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Souri A. The effect of catastrophic health expenditure on work after retirement. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2017;84(3):313–23.

Juyani Y, Hamedi D, Jebeli SSH, Qasham M. Multiple sclerosis and catastrophic health expenditure in Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(9):194.

Karami M, Najafi F, Karami Matin B. Catastrophic health expenditures in Kermanshah, west of Iran: magnitude and distribution. J Res Health Sci. 2009;9(2):36–40.

Kavosi Z, Keshtkaran A, Hayati R, Ravangard R, Khammarnia M. Household financial contribution to the health System in Shiraz, Iran in 2012. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(5):243.

Kavosi Z, Rashidian A, Pourmalek F, Majdzadeh R, Pourreza A, Mohammad K, et al. Measuring household exposure to catastrophic health care expenditures: a Longitudinal study in Zone 17 of Tehran. Hakim Res J. 2009;12(2):38–47.

Kavosi Z, Rashidian A, Pourreza A, Majdzadeh R, Pourmalek F, Hosseinpour AR, et al. Inequality in household catastrophic health care expenditure in a low-income society of Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(7):613–23.

Khadivi R, Vafapour S, Melali M. Determination of health services utilization rate among construction workers and their families in Isfahan, Iran, in 2013. 2016.

Masaeli A, Sadeghih H, Ghanbari A. High health costs, financial catastrophic and impoverishment expenditures: concepts for policy formation. Health Inf Manag. 2011;12(2):254–61.

Mehrara M, Fazaeli A. Health finance equity in Iran: an analysis of household survey data (1382–1386). J Health Admin. 2010;13(40):51–62.

Moradi G, Safari H, Piroozi B, Qanbari L, Farshadi S, Qasri H, et al. Catastrophic health expenditure among households with members with special diseases: a case study in Kurdistan. Med J Islamic Republic Iran. 2017;31:43.

Nouraei Motlagh S, Rezapour A, Lotfi F, Adham D, Sarabi Asiabar A. Investigating adverse effects of health expenditures in households of deprived provinces. J Health. 2017;8(4):425–35.

Panahi H, Janati A, Narimani M, Assadzadeh A, Mohammadzadeh P, Naderi A. Catastrophic expenditures for hospitalized patients in Tabriz, Iran. 2014. p. 655–63.

Piroozi B, Moradi G, Nouri B, Bolbanabad AM, Safari H. Catastrophic health expenditure after the implementation of health sector evolution plan: a case study in the west of Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(7):417.

Raghfar H, Atrkar RS, Atefi M. Measurement of the fair financial contribution index and catastrophic expenditures in different regions of Iran, 1984–2010. 2013.

Rezapour A, Arabloo J, Tofighi S, Alipour V, Sepandy M, Mokhtari P, et al. Determining Equity in Household’s Health Care Payments in Hamedan Province. Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(7):480–93.

Rezapour A, Ebadifard Azar A, Asadi S, Bagheri Faradonbeh S, Toofan F. Estimating the odd-ratio of factors affecting households’ exposure to catastrophic and impoverishing health expenditures. J Mil Med. 2016;18(1):355–61.

Rezapour A, Ghaderi H, Azar F, Larijani B, Gohari MR. Effects of health out-of-pocket payment on households in iran; catastrophic and impoverishment: population based study in Tehran (2012). Life Sci J. 2013;10(3):1457–69.

Sabermahani A, Vaeze Mahdavi M, Hadian M, Asadi-Lari M. Catastrophic health expenditures and its determinants among households in Tehran in 2011, Urban HEART-2 study. Razi J Med Sci. 2014;21(126):15–26.

Soofi M, Rashidian A, Aabolhasani F, Sari AA, Bazyar M. Measuring the exposure of households to catastrophic healthcare expenditures in Iran in 2001: the World Health Organization and the World Bank’s approach. Hospital J. 2013;12(2):39–50.

Yazdi Feyzabadi V, Bahrampour M, Rashidian A, Haghdoost A, Abolhallaje M, Najafi B, et al. Incidence and intensity of catastrophic health expenditures in Iranian provinces; 2008–2014. Iran J Epidemiol. 2017;12:40–54.

Yousefi M, Assari Arani A, Sahabi B, Kazemnejad A, Fazaeli S. The financial contribution of households using by health services. J Payavard Salamat. 2015;8(6):517–27.

Anbari Z, Mohammadbeigi A, Mohammadsalehi N, Ebrazeh A. Health expenditure and catastrophic costs for inpatient-and out-patient care in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(8):1023.

Almasi M, Naderi A. Investigating the factors affecting the catastrophic costs of hemodialysis patients in Ayatollah Taleghani Hospital in Urmia. Clin Rese Allied Health Sci. 2017;5(1):57–64.

Mozafari N, et al. Evaluation of dialysis adequacy of hemodialysis patients referred to dialysis center Ardabil city. Res Sci J Ardabil Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2005;4(14):1–7.

Gotsadze G, Zoidze A, Rukhadze N. Household catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from Georgia and its policy implications. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):69.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):111–7.

O’donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation: The World Bank; 2007.

Jakovljevic M, Malmose-Stapelfeldt C, Milovanovic O, Rancic N, Bokonjic D. Disability, work absenteeism, sickness benefits, and cancer in selected european OecD countries—forecasts to 2020. Front Public Health. 2017;5:23.

Tripathy J, Prasad B, Shewade H, Kumar A, Zachariah R, Chadha S, et al. Cost of hospitalisation for non-communicable diseases in India: are we pro-poor? Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(8):1019–28.

Group AS. Financial catastrophe, treatment discontinuation and death associated with surgically operable cancer in South-East Asia: results from the ACTION Study. Surgery. 2015;157(6):971–82.

Lee J-E, Shin H-I, Do YK, Yang EJ. Catastrophic health expenditures for households with disabled members: evidence from the Korean health panel. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(3):336–44.

Ma X, Wang Z, Liu X. Progress on Catastrophic Health Expenditure in China: evidence from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2010 to 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4775.

Kimani DN, Mugo MG, Kioko UM. Catastrophic health expenditures and impoverishment in Kenya. Eur Sci J. 2016;12(15):1–15.

Berki S. A look at catastrophic medical expenses and the poor. Health Aff. 1986;5(4):138–45.

Ghosh S. Catastrophic payments and impoverishment due to out-of-pocket health spending. Econ Polit Wkly. 2011;46(47):63–70.

Joglekar R. Can insurance reduce catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditure? 2012.

Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Equity in financing healthcare: impact of universal access to healthcare in Thailand. 2008.

Somkotra T, Lagrada LP. Which households are at risk of catastrophic health spending: experience in Thailand After universal coverage: exploring the reasons why some households still incur high levels of spending—even under universal coverage—can help policymakers devise solutions. Health Aff. 2009;28(Suppl1):w467–78.

Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Can insurance increase financial risk?: the curious case of health insurance in China. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):990–1005.

Mondal S, Kanjilal B, Peters DH, Lucas H. Catastrophic out-of-pocket payment for health care and its impact on households: experience from West Bengal, India. Future Health Syst Innov equity. 2014;34(2):1303–16.

Barros AJ, Bastos JL, Dâmaso AH. Catastrophic spending on health care in Brazil: private health insurance does not seem to be the solution. Cadernos de saude publica. 2011;27:s254–62.

Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG, Salinas-Rodríguez A, Sesma-Vázquez S. Health insurance for the poor: impact on catastrophic and out-of-pocket health expenditures in Mexico. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11(5):437–47.

Li Y, Wu Q, Xu L, Legge D, Hao Y, Gao L, et al. Factors affecting catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from medical expenses in China: policy implications of universal health insurance. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:664–71.

Pal R. Analysing catastrophic OOP health expenditure in India: concepts, determinants and policy implications. 2012.

Van Minh H, Phuong NTK, Saksena P, James CD, Xu K. Financial burden of household out-of pocket health expenditure in Viet Nam: findings from the National Living Standard Survey 2002–2010. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:258–63.

Su TT, Kouyaté B, Flessa S. Catastrophic household expenditure for health care in a low-income society: a study from Nouna District, Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:21–7.

Adhikari SR, Maskay NM, Sharma BP. Paying for hospital-based care of Kala-azar in Nepal: assessing catastrophic, impoverishment and economic consequences. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(2):129–39.

Wagstaff A, Doorslaer EV. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993–1998. Health Econ. 2003;12(11):921–33.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank School of Management and Medical Informatics at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for supporting.

Funding

This study was funded (Approval code: 5/55183) by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LD conceived the study. LD supervised all phases of the study. MY and HHB were advisors in methodology and contributed to intellectual development of manuscript. BE conducted the first stage of literature review and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. EH conducted the literature review and analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.TBZMED.1395.826).

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Doshmangir, L., Yousefi, M., Hasanpoor, E. et al. Determinants of catastrophic health expenditures in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 18, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-020-00212-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-020-00212-0