Abstract

Background

Care for older adults is high on the global policy agenda. Active involvement of older adults and their informal caregivers in policy-making can lead to cost–effective health and long-term care interventions. Yet, approaches for their involvement in health policy development have yet to be extensively explored. This review maps the literature on strategies for older adults (65+ years) and informal caregivers’ involvement in health policy development.

Method

As part of the European Union TRANS-SENIOR program, a scoping review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s methodology. Published and grey literature was searched, and eligible studies were screened. Data were extracted from included studies and analysed using the Multidimensional Framework for Patient and Family Engagement in Health and Healthcare.

Results

A total of 13 engagement strategies were identified from 11 publications meeting the inclusion criteria. They were categorized as “traditional”, “deliberative” and “others”, adopting the World Bank’s categorization of engagement methods. Older adults and informal caregivers are often consulted to elicit opinions and identify priorities. However, their involvement in policy formulation, implementation and evaluation is unclear from the available literature. Findings indicate that older adults and their informal caregivers do not often have equal influence and shared leadership in policy-making.

Conclusion

Although approaches for involving older adults and their informal caregivers’ involvement were synthesized from literature, we found next to no information about their involvement in policy formulation, implementation and evaluation. Findings will guide future research in addressing identified gaps and guide policy-makers in identifying and incorporating engagement strategies to support evidence-informed policy-making processes that can improve health outcomes for older adults/informal caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One in six people worldwide will be over 65 years in 2050 [1]. Ageing is correlated with increased multimorbidity and chronic health needs. This is burdensome to older adults and their informal caregivers and significantly increases health and social care service utilization [2, 3], and the complexity of health and long-term care needs. Informal caregiving and care for older adults have become critical issues of public policy. Informal caregivers of older adults are the mainstay of support for older adults with chronic health conditions [4]. Furthermore, they are potentially at risk for adverse effects on their health and well-being, quality of life and economic security [5]. Therefore, health policy decisions are relevant to older adults and their informal caregivers and impact the healthcare system, highlighting the need to develop responsive health policies [6,7,8]. One approach to efficacious health policy development is citizen engagement [9].

When citizens are engaged in policy development, policy-makers are better aware of needs and outcomes affecting the target population [8]. Citizen engagement in policy-making can improve instrumental (designed to improve the quality of decision-making), developmental (intended to improve knowledge and capacity of the participants) and democratic (intended to meet transparency, accountability, trust and confidence goals) outcomes [10,11,12]. As such, involving older adults and their informal caregivers in health policy development improves the legitimacy and transparency of the health policy-making process and can also lead to carefully crafted, relevant policies that improve cost–effective healthcare and long-term care interventions [8, 13, 14]. However, informal caregiver and older adult input in health policy development is limited, and little is known about strategies to engage them in developing policies affecting their lives [15, 16]. Most previous research on engagement at the policy level focuses on the general population, which does not often reflect older adults’ unique and complex social and healthcare needs [17]. Policy-making would benefit from older adult and informal caregiver perspectives, as their involvement has been shown to improve policy sustainability and outcomes [6]. Finally, tangible public health outcomes emerge when active citizen participation in decision-making is promoted [18].

Engaging older adults in health policy development holds substantial public health implications, affecting diverse aspects of healthcare. This impact spans from individual older adults and informal caregivers to the broader societal level, influencing healthcare systems, policies, emerging technologies, healthcare innovation and the overall quality of care. Participation in shaping solutions and emerging health technologies enables the creation of practical and effective solutions alongside those experiencing the issues. For instance, employing collaborative methods such as creative workshops and dilemma games fosters active involvement in co-developing health technologies [19]. Similarly, involvement methods such as patient journey mapping, surveys, workshops, expert panels, user boards, public and patient involvement (PPI) conferences, Delphi methods, living laboratories for technology innovation, stakeholder activities and patient interviews have been employed in the co-development of health services [20].

Most existing research focuses on citizens’ engagement in research. For example, engaging older adults as partners in transitional care research, engaging patients in health research and engaging older adults in healthcare research and planning [21,22,23,24,25]. Previous research has also focused on involvement of older adults/informal caregivers in healthcare decision-making [26, 27] as opposed to older adult/informal caregiver engagement in health policy development. There are a few examples of older adult and informal caregiver engagement in health policy development [17, 28, 29]. However, these works include no overview nor synthesis of methods for engaging older adults and informal caregivers in health policy development. More information on strategies for their engagement is necessary to promote older adult and informal caregiver engagement in health policy development and improve outcomes linked to health policy. This review aims to provide a foundation for older adult and informal caregiver engagement in health policy development by providing an overview of available research evidence on strategies for their engagement in health and well-being policy development. The scope of this study is thus focused specifically on exploring older adult and informal caregiver involvement in government policy development rather than involvement in individual care/healthcare decision-making, and organizational governance/policy-making.

Methods

Design

Using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology, we gathered evidence on engagement strategies for older adults and informal caregivers in health policy development, and identified and analysed knowledge gaps [30]. A scoping review protocol was developed to guide the study [31]. Data analysis was guided by the Multidimensional Framework for Patient and Family Engagement in Health and Healthcare by Carman et al. [32] (Additional file 1: Appendix S1), which was influenced by Arnstein’s ladder of participation [33]. The multidimensional framework describes a continuum of engagement (consultation, involvement and partnership/shared leadership) across three levels of the healthcare system (individual care, organizational governance and government policy) and describes factors influencing engagement. This study derives the basis for analysis from the following elements adapted from the framework: the engagement continuum (consultation, involvement, partnership/shared leadership), the level/stage of government policy (agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, policy evaluation) and factors influencing policy-makers to create involvement opportunities, all described in data charting section below. Finally, we were interested in synthesizing data on reported outcomes of engagement.

There are a plethora of potentially relevant frameworks, theories and conceptualizations related to citizen engagement, such as Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation and the International Association for Public Participation (Iap2) models, among others [33,34,35,36,37,38]. However, for this study, we opted for the Multidimensional framework by Carman and colleagues. This choice was based on its ability to illustrate different levels of the healthcare system where patients and families can be engaged, a fundamental aspect of our study.

Search strategy and selection criteria

An initial search of two online databases (PubMed and Embase) was conducted. We analysed the keywords in the title and abstract of retrieved papers and the index terms used to describe the articles. A second search used all identified keywords and index terms across all relevant databases: Health Systems Evidence, Health Evidence, CINAHL, PubMed, and Embase. Thirdly, the reference lists of identified reports and articles were scanned for additional sources. We worked with three librarians for search terms and search strategy refinement. We searched grey literature (Participedia.net and Google) using a combination of indexing (Mesh) terms and the following search key words: (older adult OR aged OR senior) AND (patient participation OR empowerment OR deliberation OR activation) AND (health policy OR Advisory committee OR policy formulation; Additional file 2: Appendix S2). We refined search results from Participedia.net by using filters relating to health and well-being.

Search results were imported into EndNote 20 for de-duplication, then into an online systematic review software, Covidence (www.covidence.org). Titles and abstracts were screened to determine eligibility for full-text review. Results from the grey literature were screened by reading the titles and summaries. All five research team members screened a sample together for eligibility and discussed any doubts and differences. Then all titles and abstracts were screened independently by at least two team members. Disagreements were discussed and resolved through discussion or involving a third team member, and a consensus was reached.

Titles and abstracts of empirical studies, reviews and grey literature reports were included for full-text review if they reported on policy development in the areas of health and well-being, addressed the use or evaluation of a method for engaging older adults and/or informal caregivers in health and well-being policy development, focused on older adults (defined as persons with a minimum age of 65 years; a majority of participants were aged 65 years and above) and/or their informal caregivers, or used proxy words (such as chronically ill, dementia and frail elderly), and addressed policy development at regional, national or international level. In the screening of titles and abstracts, we specifically sought studies that identified participants as either older adults aged 65 years and above, informal caregivers or a combination of both. For full-text screening, we checked for the actual ages and percentage of participants aged 65 years and above. Studies that only included participants younger than 65 years were excluded. Articles with a majority of 65 years and older were included. Corresponding authors of full-text articles were contacted for clarity when the sample population was unclear. Articles were not included in this review when there was no response.

Empirical studies, reviews and grey literature reported in all languages and from the databases’ inception were included. Titles and abstracts of included studies in languages other than English were first screened by a colleague able to read the applicable language to decide on its relevance for extraction. Studies describing older adult and informal caregiver engagement in research or in healthcare decision-making were excluded. We excluded articles describing engagement for organizational governance/policy development. Studies that involved heterogeneous population groups (for example, older adults/informal caregivers and health workers, or government representatives) were excluded. Finally, studies whereby we could not access the full texts were excluded.

Data charting

Based on the elements of the multidimensional framework for patient and family engagement in health and healthcare [32], a preliminary data charting table (Additional file 3: Appendix S3) was developed and piloted by two team members who also extracted the data. In case of discrepancies, a third team member reviewed for extraction agreement. Data charting followed the following elements – continuum of engagement, stages of government policy development and factors influencing policy-makers to create engagement opportunities. Additionally, data were extracted on outcomes of engagement which we defined as the result of engaging older adults in health policy development.

The engagement continuum is categorized based on how much information flows between parties (policy-maker and citizens), and the level of influence citizens have over decision-making ranging from limited participation, or degrees of tokenism, to a state of collaborative partnership in which citizens share leadership or control decisions. The engagement continuum, according to Carman et al., includes consultation (eliciting opinions about health issues), involvement (when research recommendations influence policy) and partnership/shared leadership (when citizens and policy-makers share equal power and responsibility in decision-making) [32].

Levels of engagement in the framework was modified to “levels/stages of policy development” since we were particularly focused on engagement in policy development. We focused on these stages of the policy cycle: agenda setting (identifying priorities, recognition of issues as a problem demanding public attention), policy formulation (developing and refining policy options for government), policy implementation (activities taken to achieve goals stated in policy statement) and policy evaluation (examination of the effects ongoing policies and public programs have on their targets in terms of the goals they are meant to achieve) [39]. Factors influencing engagement were modified to factors influencing policy-makers to create opportunities for engagement, as this was a gap in the framework this review set out to fill to build on the framework.

Results

Study selection

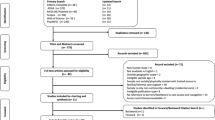

The published and grey literature search yielded 10 921 publications. After removing duplicates, 7486 articles were included for the title and abstract screening. We excluded 7385 articles for irrelevance. Altogether, 101 articles were assessed for full-text eligibility, 90 articles were excluded and data were extracted from 11 publications (Fig. 1). We identified the engagement methods in the relevant articles and described how they were used to engage participants in health policy development. Then, we interpreted these findings on the basis of the elements in the framework.

Study characteristics

The studies included were conducted in countries in North America [40,41,42] (n = 3), Europe [17, 43,44,45] (n = 4), Australia [46,47,48] (n = 3) and Asia [29] (n = 1). Publication dates of included studies ranged from 1997 to 2021. The design of the studies included a multi-method design [45] (n = 1), qualitative designs [17, 29, 40,41,42,43, 46, 47] (n = 8), a quantitative design [48]) (n = 1) and a case study design [44] (n = 1; Table 1). About half of the studies [17, 41, 44, 45, 47, 48] (n = 6) involved both older adults and their informal caregivers. Four studies [40, 42, 43, 46] involved only older adults, and one study [29] involved only informal caregivers in health policy development. A wide range of older adults (people with chronic illnesses, dementia, complex health and social needs, and home-bound older adults) and their informal caregivers were included in the studies. Finally, some engagement strategies were implemented as a one-time event, while others were ongoing or continued for a longer period of time.

Engagement strategies

A total of 13 unique engagement strategies were reported across the 11 included articles. We adopted the World Bank Groups’ categorization of citizen engagement being traditional consultation and feedback mechanisms, participatory mechanisms and citizen-led mechanisms [49]. For this review, we slightly adjusted these categories to traditional strategies, deliberative strategies, and other strategies (see Additional file 4: Appendix S4 for definition of terms). Traditional engagement strategies (interviews, surveys, focus groups, workshops, telephone conferencing) were categorized as such, as they are commonly used strategies not unique for engagement (for example, also used for research purposes) and generally designed to measure the prevalence and range of opinions and not their stability or depth [50, 51]. Deliberative strategies (citizen juries, citizen panels, community juries, policy café and carers assembly) were thus categorized, as they highlight participants’ prior education on the topic of discussion (for example, using citizen briefs and expert witnesses), thus eliciting informed views and perspectives on complex topics [50]. The “other strategies” category under which we classified a discrete choice experiment and two visual engagement strategies (photo elicitation and photovoice and audio recording) were so categorized under a general heading “other engagement strategies”, as they did not fit into the traditional or deliberative categories.

Traditional engagement strategies only (n = 5) were reported in four articles [42, 44, 45, 47], deliberative strategies only (n = 4) were reported in three articles [17, 41, 46], one article reported using one deliberative method and two traditional methods [29], and the remaining three articles [40, 43, 48] reported “other” engagement strategies. The strategies engaged participants in a wide range of health policy issues, most of which related to older adults. One article used carers assembly to engage caregivers of people with dementia to discuss issues of concern to them and to identify priorities to bring to policy-makers about to make important legislative decisions on the future provision of home care in Ireland [17]. Traditional engagement strategies were used to engage participants on recommendations for improving care for people with chronic illnesses (semi-structured interviews), priorities for older adults with multiple long-term conditions (survey, interview, workshop), quality of life and care in nursing homes, medication reimbursement (focus group, telephone interview), eldercare and informal caregiver policy (policy café and carers assembly) and health-related concerns of homebound people (survey, interview, group discussion, telephone conferencing). Deliberative methods were used to engage participants on government-funded mammography screening (community jury), long-term care provision (citizen jury with interview and focus group), post-diagnosis support/home care legislation (policy café and carers assembly) and hospital-to-home care transitions (citizen panels). Finally, other methods engaged participants in consumer-directed care (discrete choice experiment), age-friendliness of a rural community (photo-elicitation) and improving neighbourhood food and physical environment (photovoice and audio recording). Table 2 presents a summary of the engagement strategies, their descriptions and examples of health policy issues addressed.

Synthesis of result according to Carman et al.’s framework

Continuum of engagement

Identified engagement strategies varied in the level of influence (engagement continuum) participants had, with no clear relationship between engagement approach and continuum of involvement. In all, 4 of the 11 included articles reported engagement approaches on the lower end of the engagement continuum (that is, views on and experiences with a health issue were elicited [45,46,47,48]. Six articles [17, 29, 40,41,42,43] reported engagement approaches best situated in between the consultation and involvement continuum (that is, in addition to simply eliciting views and experiences, participants’ opinions were used for advocacy, development and presentation of research evidence and policy recommendations to policy-makers). This is a newly added component to the Framework. Finally, one article [44] reported engagement strategies with characteristics fitting the involvement continuum (that is, older adults’ inputs to contributed to changes in service provisions). No article reported engagement strategies reflecting participants’ involvement on the highest end of the continuum (partnership/shared leadership; Fig. 2). The level of power and decision-making authority that older adults and informal caregivers had was not a function of the engagement approach/category. Thus, it was impossible to establish a clear relationship between individual engagement approaches/the category they belong to, and the engagement continuum. For example, three unique traditional engagement strategies (interviews, surveys, and workshops) belonged to the consultation continuum, thus indicating that older adults/caregivers involved using those approaches had a lower level of power in decision-making. Contrastingly, another article described similar traditional engagement strategies (survey, interviews, group discussions and telephone conferencing), but older adult and informal caregivers involved had a higher level of influence in decision-making (involvement continuum) as shown in Table 3.

Stages of policy development

Regarding the stages of policy development, none of the 11 studies described older adults and their informal caregivers’ involvement beyond the agenda/priority-setting stage of policy development. Their role in the process of policy formulation, implementation and evaluation was not clear. Most of the studies reported participant involvement in identifying health priority issues or care needs and examining how citizen involvement can be actualized. Also, no studies reported on factors influencing policy-makers to create engagement opportunities.

Outcomes of engagement

Of the 11 studies, 8 reported on outcomes of older adult/informal caregiver engagement in policy development. Outcomes reported in the studies included but were not limited to developmental outcomes (civic education of citizens, citizens’ developed capacity to participate in public policy issues) [29, 45, 46] and instrumental outcomes (promotion of active citizenship and awareness of lived experiences of other older adults) [17, 29]. Other outcomes included increased health and information access, quality of life and self-esteem of participants [44]; provision of reform solutions [47]; and priorities for policy-makers [17]. Finally, some engagement strategies were reportedly used in isolation [41, 43, 46,47,48], while others were combined with one [17, 40, 42, 45] or more than one [29, 44] engagement method.

Discussion

This review synthesized existing literature on strategies for engaging older adults and informal caregivers in health and well-being policy development. Findings suggest that, although older adults and informal caregivers were consulted for identifying priorities and to elicit their opinions on health issues, they were rarely engaged in the actual processes of policy formulation, implementation and evaluation. They also rarely had shared leadership and decision-making authority. None of the included studies provided data on factors influencing policy-makers to create engagement opportunities and data on comparisons of alternative engagement strategies for variation, content, breadth and depth of participants’ input.

Our categorization of engagement methods into “traditional”, “deliberative” and “others” is in line with previous research suggesting the same. For example, the World Bank categorized engagement mechanisms as traditional and consultative feedback mechanisms (including surveys and focus groups), participatory mechanisms and citizen-led mechanisms. Similarly, approaches such as citizen juries, community juries, citizen panels and policy cafés have been described as deliberative engagement methods in previous literature, usually characterized by the presenting research evidence or using expert witnesses to educate lay citizens to make reasoned and informed judgement on complex issues [17, 50, 52, 53]. Finally, photovoice and audio-recording and photo elicitation, categorized under the other category with the discrete choice experiment, have been described in previous research as visual research methodologies [54, 55].

Furthermore, findings from this review indicate that the engagement of older adults in policy-making often relies solely on consultation approaches [15] and takes place at the beginning stages of the policy cycle through older adult and informal caregiver consultation and priority identification. However, meaningful participation involves stakeholders in all stages of the policy cycle. This includes research, data collection, priority setting, policy formulation, budgeting, implementation and review and evaluation [15, 56]. Thus, future research can be conducted to increase our understanding of older adult and informal caregiver involvement in the higher end of engagement continuum as well as how or when in the policy cycle/process they are involved.

Most of the engagement strategies reported in this review involved participants directly and not through advisory bodies or organizations of older persons, although some collaborations and partnerships with other stakeholders were necessary in some cases to reach the older adults and their informal caregivers [17, 40, 43, 44]. Also worthy of note is the fact that leveraging on partnerships, institutionalizing engagement and community-based partnerships is critical to enabling desired engagement outcomes [12, 40, 43, 44]. Finally, the literature on engagement strategies for other populations can be useful to inform future empirical work on engagement strategies for older adults aged 65 years and above. These strategies include the participatory theatre approach [57], concept maps [58], deliberative polling and citizen dialogues [59].

Although our research focuses solely on identifying literature that describes the use and evaluation of older adults and informal caregivers involvement approaches, we recognize that older persons or informal caregivers’ participation in policy-making can take place both in individual and collective settings [60]. Thus, there may be other engagement approaches that accommodate older adults and informal caregivers in group settings with other stakeholders and not as the sole participants, for example, public consultations on the living conditions of seniors which involved older adults, representatives of health and social services, and elected members of city councils [61]. The choice of engagement approach may be dependent on existing policy processes within a particular setting, for example, senior councils in Europe for supporting local political decision-making. Also, Keogh and colleagues [17] designed innovative methods for involving people with dementia in policy development, using a world café methodology and citizen assembly model commonly implemented in Ireland [17, 62].

The evaluation of engagement methods has been minimal. Understanding the effectiveness of engagement strategies is fundamental to informing the design of successful engagement and reaching the full potential of engagement [16, 63,64,65]. This review discusses existing engagement strategies, but it does not address which may be most effective for older adults and informal caregivers based on the context/health system. One of the excluded studies (on the basis of the age criterion) reported on the evaluation of engagement strategies. Two deliberative methods of public participation – the citizens’ workshop and the citizens’ jury – were evaluated. The evaluation of the methods was based on process and outcome evaluation measures [66], and found that both methods were not rated significantly differently by the participants on most criteria, thus, signalling an overlap in the impact and utility of the two methods of deliberation. There is need for more studies on the evaluation of engagement strategies for involving older adults 65 years and older and their informal caregivers in health policy development.

Having established that research is needed around the evaluation of engagement methods, we also need to provide the older adults and informal caregivers with the necessary skills needed to educate themselves about the process of policy-making as well as advocacy training. Engaging them in advocacy has the potential to achieve better local policy outcomes [40]. For example, one excluded study (on the basis of the age criterion) reported the evaluation of a senior civic academy (SCA) methodology: a self-advocacy course that simultaneously educates older residents about policy-making processes and engages them in advocacy training to incorporate their voices in local policy and planning. A pre- and post-program evaluation, as well as follow-up interviews, were conducted [67]. The study reported the efficaciousness of the methodology in engaging older adults. Advocacy training can be provided for older adults and informal caregivers on advocating for policy changes. Training components may include building a case for change, identifying potential allies and resources, and role-playing scenarios targeting local policy-makers [40]. Finally, civil society organizations and older adult organizations also play a role in building the skills of older persons to engage in advocacy with governments, thus creating a space for them to tell their own stories from their perspectives to inform policy-making [56].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first attempt we can identify to synthesize evidence on strategies for engaging older adults and informal caregivers in health policy development. We used the Multidimensional Framework for Patient and Family Engagement in Health and Healthcare to guide data extraction and analysis, thus providing a theoretical contribution to the literature.

Some limitations were, however, identified. First, although the review was not sufficient to provide information to build on the framework (for example, it was not clear how or whether older adults and their informal caregivers are involved in all the stages/cycle of policy development; also no factors influencing policy-makers to create opportunities for involvement were identified), gaps in the literature were identified, providing direction for future studies. Secondly, due to the ambiguity and heterogeneity of terminology for engagement, the search string for this review, although built with the help of librarians, may not have identified all relevant published and grey literature. Quality appraisal, which is an evaluation of the quality of the included publications, was not performed, since our objective was to identify and describe the range of literature available on the topic without excluding studies on the basis of methodological quality. Furthermore, our intention was to provide a comprehensive overview of the field rather than to evaluate the quality of individual studies. Also, quality appraisal is not required in scoping review methods. Finally, our research focused solely on engagement approaches that were used exclusively for older adults and informal caregivers; thus, we may have missed out on publications reporting approaches that include other citizens and stakeholders alongside older adults and informal caregivers.

Implications for future research and policy

An examination of the existing literature points to a dearth of literature on the use and evaluation of engagement strategies for older adults aged 65 years and above and their informal caregivers. Implications for future research include understanding different healthcare systems and contexts in which these methods were used, understanding factors influencing policy-makers to create engagement opportunities for them and researching methods for evaluating and assessing engagement strategies for variation, content, breadth and depth of participants’ input.

Policy-makers can learn from the findings of this review by understanding how older adults and informal caregivers can be involved in policy process using the identified approaches. Engaging older adults and their informal caregivers in health policy formulation, implementation and evaluation beyond just consultations and tokenism [33] but also, in the continuum of involvement and partnership/shared leadership, requires a concerted effort of all stakeholders, including researchers, policy-makers, older adults’ representative organizations and older adults and their informal caregivers.

Conclusion

The analysis shows a dearth in literature on the use and evaluation of strategies for engaging older adults and informal caregivers in health policy development. The small number of studies reviewed could indicate a need to further explore older adult and informal caregiver involvement in collective settings including other stakeholders. Finally, this review highlights gaps in strategies for involving older adults and informal caregiver, and provides relevant information to enable policy-makers to make evidence-informed and responsive policy decisions, thus improving health outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

All data are publicly available and included within the article and its supplementary information files.

References

UNDESA. World population ageing. Highlights: living arrangements of older persons. New York: United Nations; 2020. p. 2020.

Gauvin FP, Abelson J, Giacomini M, Eyles J, Lavis JN. “It all depends”: conceptualizing public involvement in the context of health technology assessment agencies. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2010;70(10):1518–26.

Abdi S, Spann A, Borilovic J, de Witte L, Hawley M. Correction to: Understanding the care and support needs of older people: a scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):23.

Schulz R, Eden J, Adults C on FC for O, Services B on HC, Division H and M, National Academies of Sciences E. Recommendations to support family caregivers of older adults. Families Caring for an Aging America. National Academies Press (US); 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396408/. Accessed 19 Feb 2023.

Schulz R, Eden J, Adults C on FC for O, Services B on HC, Division H and M, National Academies of Sciences E. Family caregiving roles and impacts. Families Caring for an Aging America. National Academies Press (US); 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396398/. Accessed 19 Feb 2023.

Stefanoni, S., & Williamson, C. Review of Good Practice in National Policies and Laws on Ageing. HelpAge International Asia, Pacific Regional Development Centre (HAI). 2015. www.helpage.org/Worldwide/AsiaPacific.

de Freitas C, Martin G. Inclusive public participation in health: policy, practice and theoretical contributions to promote the involvement of marginalised groups in healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2015;135:31–9.

Irvin RA, Stansbury J. Citizen participation in decision making: is it worth the effort? Public Adm Rev. 2004;64(1):55–65.

Figueiredo Nascimento S, Cuccillato, E., Schade, S., Guimarães Pereira, A. Citizen Engagement in Science and Policy-Making. 2016. Report No.: EUR 28328 EN. https://doi.org/10.2788/40563

Conklin A, Morris Z, Nolte E. What is the evidence base for public involvement in health-care policy?: results of a systematic scoping review. Health Expect. 2015;18(2):153–65.

Gaventa J, Barrett G. Mapping the outcomes of citizen engagement. World Dev. 2012;40(12):2399–410.

Abelson J, Stephanie M, Kathy L, Gauvin FP, Martin E. Effective strategies for interactive public engagement in the development of healthcare policies and program; 2010. p. 49. www.chsrf.ca

Carman K, Heeringa J, Heil S, Garfinkel S, Windham A, Gilmore D, et al. Public deliberation to elicit input on health topics: findings from a literature review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Report No.: AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC070-EF. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov.

Cylus, J., Normand, Charles, & Figueras, J. The economics of healthy and active ageing series will population ageing spell the end of the of the welfare state?: A review of evidence and policy options. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2019. (pp. 1–43). https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/will-population-ageing-spell-the-end-of-the-welfare-state-a-review-of-evidence-and-policy-options-study.

Falanga R, Cebulla A, Principi A, Socci M. The participation of senior citizens in policy-making: patterning initiatives in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):34.

Holroyd-Leduc J, Resin J, Ashley L, Barwich D, Elliott J, Huras P, et al. Giving voice to older adults living with frailty and their family caregivers: engagement of older adults living with frailty in research, health care decision making, and in health policy. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2(1):23.

Keogh F, Carney P, O’Shea E. Innovative methods for involving people with dementia and carers in the policymaking process. Health Expect. 2021;24(3):800–9.

Brusaferro S, Arnoldo L, Brunelli L, Croci R, Mistretta A. Six Ps to drive the future of public health. J Public Health. 2022;44(1):i94–6.

Clemensen J, Rothmann MJ, Smith AC, Caffery LJ, Danbjorg DB. Participatory design methods in telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(9):780–5.

Cluley V, Ziemann A, Feeley C, Olander EK, Shamah S, Stavropoulou C. Mapping the role of patient and public involvement during the different stages of healthcare innovation: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2022;25(3):840–55.

Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, Vandall-Walker V. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):5.

McNeil H, Elliott J, Huson K, Ashbourne J, Heckman G, Walker J, et al. Engaging older adults in healthcare research and planning: a realist synthesis. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2(1):10.

Ganann R, McAiney C, Johnson W. Engaging older adults as partners in transitional care research. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(Suppl):S40–1.

Kylén M, Slaug B, Jonsson O, Iwarsson S, Schmidt SM. User involvement in ageing and health research: a survey of researchers’ and older adults’ perspectives. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):93.

Maulod A, Rouse S, Lee A, Ravindran M, Mohamad H, Goh V, et al. Ethics of participation and social inclusion of older persons in research: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(S1):126.

Kraun L, De Vliegher K, Vandamme M, Holtzheimer E, Ellen M, van Achterberg T. Older peoples’ and informal caregivers’ experiences, views, and needs in transitional care decision-making: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;134: 104303.

Elliott J, McNeil H, Ashbourne J, Huson K, Boscart V, Stolee P. Engaging older adults in health care decision-making: a realist synthesis. Patient. 2016;9(5):383–93.

Frączkiewicz-Wronka A, Kowalska-Bobko I, Sagan A, Wronka-Pośpiech M. The growing role of seniors councils in health policy-making for older people in Poland. Health Policy. 2019;123(10):906–11.

Chuengsatiansup K, Tengrang K, Posayanonda T, Sihapark S. Citizens’ Jury and elder care: public participation and deliberation in long-term care policy in Thailand. J Aging Soc Policy. 2019;31(4):378–92.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Kolade O, Porat-Dahlerbruch J, van Achterberg T, Ellen M. Strategies for engaging senior citizens and their informal caregivers in health policy development: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10): e064505.

Carman K, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):223–31.

Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann. 1969;35(4):216–24.

International Association for Public Participation Australasia (IAP2). IAP2 Australasia. Quality assurance standard for community and stakeholder engagement. https://www.iap2.org.au/Resources/IAP2-Published-Resources. Accessed 20 Dec 2023.

Wiles LK, Kay D, Luker JA, Worley A, Austin J, Ball A, et al. Consumer engagement in health care policy, research and services: a systematic review and meta-analysis of methods and effects. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1): e0261808.

Masterson D, Areskoug Josefsson K, Robert G, Nylander E, Kjellström S. Mapping definitions of co-production and co-design in health and social care: a systematic scoping review providing lessons for the future. Health Expect. 2022;25(3):902–13.

Bright FAS, Kayes NM, Worrall L, McPherson KM. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(8):643–54.

Caputo F, Prisco A, Lettieri M, Crescenzo M. Citizens’ engagement in smart cities for promoting circular economy. A Knowledge based framework. ITM Web Conf. 2023;51:02001.

Howlett M, Giest S. Policy Cycle. In: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier; 2015. p. 288–92. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780080970868750318. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Buman MP, Winter SJ, Baker C, Hekler EB, Otten JJ, King AC. Neighborhood Eating and Activity Advocacy Teams (NEAAT): engaging older adults in policy activities to improve food and physical environments. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(2):249–53.

Gauvin F, McKinlay J, Markle-Reid M, Ganann R, McAiney C, Heald-Taylor G, et al. Panel summary: engaging older adults with complex health and social needs, and their caregivers, to improve hospital-to-home transitions in Ontario. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum; 2019.

Chappell NL, Maclure M, Brunt H, Hopkinson J, Mullett J. Seniors’ views of medication reimbursement policies: bridging research and policy at the point of policy impact. Can Public Policy Anal Polit. 1997;23:114.

Harrison A, Hall M, Money A, Mueller J, Waterson H, Verma A. Engaging older people to explore the age-friendliness of a rural community in Northern England: a photo-elicitation study. J Aging Stud. 2021;58: 100936.

O’Keefe E, Hogg C. Public participation and marginalized groups: the community development model: public participation and marginalized groups. Health Expect. 1999;2(4):245–54.

Spiers G, Boulton E, Corner L, Craig D, Parker S, Todd C, et al. What matters to people with multiple long-term conditions and their carers? Postgrad Med J. 2021;99:159–65.

Degeling C, Barratt A, Aranda S, Bell R, Doust J, Houssami N, et al. Should women aged 70–74 be invited to participate in screening mammography? A report on two Australian community juries. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6): e021174.

Jowsey T, Yen L, Wells R, Leeder S. National Health and Hospital Reform Commission final report and patient-centred suggestions for reform. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(2):162.

Kaambwa B, Lancsar E, McCaffrey N, Chen G, Gill L, Cameron ID, et al. Investigating consumers’ and informal carers’ views and preferences for consumer directed care: a discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:81–94.

World Bank Group. Strategic Framework for Mainstreaming Citizen Engagement in World Bank Group Operations. Washington, DC: © World Bank; 2014. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21113

Carman KL, Mallery C, Maurer M, Wang G, Garfinkel S, Yang M, et al. Effectiveness of public deliberation methods for gathering input on issues in healthcare: results from a randomized trial. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:11–20.

Fishkin JS, Rosell SA, Shepherd D, Amsler T. ChoiceDialogues and deliberative polls: two approaches to deliberative democracy. Natl Civ Rev. 2004;93(4):55–63.

Degeling C, Carter SM, Rychetnik L. Which public and why deliberate? – A scoping review of public deliberation in public health and health policy research. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131:114–21.

Degeling C, Rychetnik L, Street J, Thomas R, Carter SM. Influencing health policy through public deliberation: lessons learned from two decades of citizens’/community juries. Soc Sci Med. 2017;179:166–71.

Lorenz LS, Kolb B. Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expect. 2009;12(3):262–74.

Mysyuk Y, Huisman M. Photovoice method with older persons: a review. Ageing Soc. 2020;40(8):1759–87.

UNECE. Meaningful participation of older persons and civil society in policymaking|UNECE. 2021. https://unece.org/statistics/documents/2021/08/meaningful-participation-older-persons-and-civil-society-policymaking. Accessed 31 Mar 2023.

Bailey C, Forster N, Douglas B, Webster Saaremets C, Salamon E. Housing voices: using theatre and film to engage people in later life housing and health conversations. Hous Care Support. 2019;22(4):181–92.

Bacsu J, McIntosh T, Viger M, Johnson S, Jeffery B, Novik N. Supporting older adults’ engagement in health-care programs and policies: findings from a rural cognitive health study. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2019;38(3):209–23.

Ellen M, Shach R, Kok M, Fatta K. There is much to learn when you listen: exploring citizen engagement in high- and low-income countries. World Health Popul. 2017;17(3):31–42.

Pinto JM, Neri AL. Trajectories of social participation in old age: a systematic literature review. Rev Bras Geriatr E Gerontol. 2017;20(2):259–72.

Hebert R. An urgent need to improve life conditions of seniors. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(8):711–4.

Citizensinformation.ie. Citizens’ Assembly. Citizensinformation.ie. https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/government_in_ireland/irish_constitution_1/citizens_assembly.html. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):239–51.

Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A, Lozza E. Measuring patient engagement: development and psychometric properties of the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) Scale. Front Psychol. 2015;6:274.

Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):98.

Timotijevic L, Raats MM. Evaluation of two methods of deliberative participation of older people in food-policy development. Health Policy. 2007;82(3):302–19.

Bui CN, Coyle CE, Freeman A. Promoting self-advocacy among older adults: lessons from Boston’s senior civic academy. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(4):452–8.

Smith KE, Macintyre AK, Weakley S, Hill SE, Escobar O, Fergie G. Public understandings of potential policy responses to health inequalities: evidence from a UK national survey and citizens’ juries in three UK cities. Soc Sci Med. 2021;291: 114458.

Creswell J, Poth C. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications; 2016.

Fife-Schaw, C., & Rowe, G. Monitoring and modelling consumer perceptions of food-related risks. A report for the UK Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, University of Surrey, Guildford. 1995.

Thomas R, Sims R, Degeling C, Street JM, Carter SM, Rychetnik L, et al. CJCheck Stage 1: development and testing of a checklist for reporting community juries – Delphi process and analysis of studies published in 1996–2015. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):626–37.

Paul C, Nicholls R, Priest P, McGee R. Making policy decisions about population screening for breast cancer: the role of citizens’ deliberation. Health Policy. 2008;85(3):314–20.

Gauvin F. Citizen panels program. London: McMaster Health Forum; 2017.

Abelson J, Bombard Y, Gauvin FP, Simeonov D, Boesveld S. Assessing the impacts of citizen deliberations on the health technology process. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):282–9.

Löhr K, Weinhardt M, Sieber S. The “world café” as a participatory method for collecting qualitative data. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940692091697.

Farrell DM, Suiter J, Harris C. ‘Systematizing’ constitutional deliberation: the 2016–18 citizens’ assembly in Ireland. Ir Polit Stud. 2019;34(1):113–23.

van den Broek-Altenburg E, Atherly A. Using discrete choice experiments to measure preferences for hard to observe choice attributes to inform health policy decisions. Health Econ Rev. 2020;10(1):18.

Peng Y, Jiang M, Shen X, Li X, Jia E, Xiong J. Preferences for primary healthcare services among older adults with chronic disease: a discrete choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1625–37.

Shaw PA. Photo-elicitation and photo-voice: using visual methodological tools to engage with younger children’s voices about inclusion in education. Int J Res Method Educ. 2021;44(4):337–51.

Ronzi S, Pope D, Orton L, Bruce N. Using photovoice methods to explore older people’s perceptions of respect and social inclusion in cities: opportunities, challenges and solutions. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:732–45.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Thomas Vandendriessche and Chayenne Van Meel, librarians at KU Leuven and Ruth Suhami, a librarian at Tel-Aviv University.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 812656. The sponsors had no role in the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm that study conception and design was by ME and TvA. OK prepared the initial draft of the manuscript with substantial contributions from JP-D. RM performed a secondary review of full-text articles. OK developed the data extraction instrument. OK and RM performed the piloting of the data extraction instrument. All authors contributed to the title and abstract article screening and data analysis, reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical review is not required, as the scoping review is a form of secondary data analysis that synthesizes data from publicly available sources.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix S1.

A Multidimensional Framework for Patient and Family Engagement in Health and Healthcare by Carman et al. [25].

Additional file 2: Appendix S2.

Search strategy.

Additional file 3: Appendix S3.

Data charting table.

Additional file 4: Appendix S4.

Definition of terms.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolade, O.R., Porat-Dahlerbruch, J., Makhmutov, R. et al. Strategies for engaging older adults and informal caregivers in health policy development: A scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys 22, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01107-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01107-9