Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with provoked thrombo-inflammatory responses. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic this was thought to contribute to hypercoagulability and multi-organ system complications in infected patients. Limited studies have evaluated the impact of therapeutic anti-coagulation therapy (AC) in alleviating these risks in COVID-19 positive patients. Our study aimed to investigate whether long-term therapeutic AC can decrease the risk of multi-organ system complications (MOSC) including stroke, limb ischemia, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, in-hospital and intensive care unit death in COVID-19 positive patients hospitalized during the early phase of the pandemic in the United States.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted of all COVID-19 positive United States Veterans between March 2020 and October 2020. Patients receiving continuous outpatient therapeutic AC for a least 90 days prior to their initial COVID-19 positive test were assigned to the AC group. Patients who did not receive AC were included in a control group. We analyzed the primary study outcome of MOSC between the AC and control groups using binary logistic regression analysis (Odd-Ratio; OR).

Results

We identified 48,066 COVID-19 patients, of them 879 (1.8%) were receiving continuous therapeutic AC. The AC cohort had significantly worse comorbidities than the control group. On the adjusted binary logistic regression model, therapeutic AC significantly decreased in-hospital mortality rate (OR; 0.67, p = 0.04), despite a higher incidence of GI bleeding (OR; 4.00, p = 0.02). However, therapeutic AC did not significantly reduce other adverse events.

Conclusion

AC therapy reduced in-hospital death early in the COVID-19 pandemic among patients who were hospitalized with the infection. However, it did not decrease the risk of MOSC. Additional trials are needed to determine the effectiveness of AC in preventing complications associated with ongoing emerging strains of the COVID-19 virus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Early in the Coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) pandemic, this viral illness was a pervasive public health threat. In October 2021, the cumulative number of global cases had exceeded 240 million with nearly 5 million deaths. In addition to the interactions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus with human cells, severe COVID-19 disease was associated with a provoked hypercoagulable state that resulted in microvascular angiopathy and thromboembolic complications [1, 2]. Likewise, marked elevations in coagulation markers such as D-dimer were associated with severe COVID-19 disease states and increased mortality [3].

Cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and coronary artery disease were highly prevalent among COVID-19 patients and carried a higher risk of morbid events as well as in-hospital mortality [4, 5]. Although acute respiratory distress syndrome was one of the hallmarks of the COVID-19 viral infection, multi-organ system complications (MOSC) was observed in patients with severe disease. A proportion of these patients presented with cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, myocarditis and acute heart failure [6]. Early in the pandemic, cardiac injury was a common occurrence and conferred a higher risk of in-hospital mortality [7]. In addition to cardiac ischemia noted in autopsy studies, pathological micro-thrombosis was a common observation among patients with severe COVID-19 illness, suggesting a pro-thrombotic state may be contributing to these cardiovascular complications and overall poor recovery outcomes [8, 9].

Since the early phase of the pandemic there has been an abundance of evidence to suggest that thrombosis alongside inflammation contributed to the poor outcomes observed with COVID-19 illness. The impact of anticoagulation in improving outcomes in already infected COVID-19 patients was therefore previously explored. In one multiplatform randomized controlled clinical trial, administration of therapeutic anticoagulation appeared to reduce thrombotic complications but not improve cardiopulmonary outcomes in already hospitalized critically-ill patients with COVID-19 [10,11,12]. It is argued that hypercoagulable states associated with COVID-19 infection are often present during the early phase of the disease process, and this could in part account relatively modest benefits observed with therapeutic anticoagulation.

However, the data regarding the role of chronic anticoagulation in outcomes of COVID-19 has since remained conflicting. Parker et al. reported reduced rates of mechanical ventilation (8.5% vs 17.4%) in chronically anticoagulated patients with COVID-19 but a higher (40.2% vs 30%) mortality rate [13]. On the other hand, Tremblay et al. demonstrated no mortality benefit in a propensity matched cohort of 241 patients receiving anticoagulation prior to COVID-19 infection [14]. As such, we sought to evaluate the incidence of multisystem organ failure in individuals with high cardiovascular risks during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesize that patient who contracted COVID-19 during this time period, while already receiving therapeutic anticoagulation would have potentially benefited from reduced COVID-19-related complications.

Methods

Patient population

We evaluated 48,066 COVID-19 positive U.S. Veterans who received care at the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) during the early phase of the COVID 19 pandemic in the U.S. between March 1, 2020 and October 29, 2020. The VA collects data from routine medical visits and compiles and stores them in a secure Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Patient information was de-identified before use in this study. This study was conducted retrospectively, and was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the institutional review board of the Department of Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

Patients were assigned to the AC group if they received a continuous outpatient prescription of therapeutically dosed anticoagulants at least 90 days prior to onset of COVID-19. Assumptions that were made during the construction of this cohort included patients with a minimum of a 30-day supply of therapeutic AC prescription at any given time, patients with apparent duplicates of therapeutic AC regimens were counted as a single patient, and a 7-day gap in therapeutic AC was allowed in the first 60 to 90 days of the screening criteria.

Study variables

Patients with a COVID-19 positive test were identified from the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource, and confirmed from a combination of laboratory results and physician notes. Determination of therapeutic anticoagulant prescription dosing for assignment to the AC group was ascertained from the CDW outpatient pharmacy domain. Incidence of MSOC, between 5–30 days after initial COVID-19 positive status of stroke, limb ischemia, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, in-hospital death, intensive care unit (ICU) death, as well as composite MSOC outcomes were identified from International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes in CDW outpatient and inpatient encounters domains. Admission outcomes between 1–30 days after initial COVID-19 positive status related to hospitalization, ICU admission, death while in the hospital, death while in the ICU, hospital maximum length of stay, and ICU maximum length of stay were also extracted from the CDW inpatient encounters domain and the VA vital status database (date of death).

Study covariates included patient demographic information, including age, race, sex, and smoking status; prescription of medications including Aspirin, Insulin, and Statin; and clinical co-morbidities, before and after initial COVID-19 positive test, including hyperlipidemia (HPL), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction (MI), diabetes (DM), hypertension (HTN), peripheral arterial disease (PAD), carotid artery stenting (CAS), chronic kidney disease (CKD), aortic valve replacement/ mitral valve repair (AVR/MVR), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), venous thromboembolism (VTE). Demographic information was collected from the CDW patient domain. The CDW outpatient pharmacy domain contained data for medication use. Patient clinical status was identified using ICD-10 diagnosis codes in CDW outpatient and inpatient encounter domains.

Propensity matching

To reduce confounding caused by unbalanced covariates in the anticoagulant group and control group, we also performed propensity score analyses. The number of patients in the control group are about 53 times that of the anticoagulant group. Since there is little to gain in terms of statistical efficacy with over 4 controls to 1 case [15], we studied 1:1, 1:2, 1:3 and 1:4 matching. We used greedy nearest neighbor matching without replacement within 0.25 caliper method to form 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4 matching with propensity score, then chose the best matching ratio for entire cohort. Similarly, we performed the same propensity score analysis separately in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, as well as in hospitalized ICU and non-ICU patients. Standardized mean difference pre- and post-1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4 matching was performed to assess the quality of the propensity methods. From this, 1:2 and 1:4 matching appeared to be the best quality. We applied the same methods to hospitalized and ICU cohorts, and observed that 1:4 matching provided the best quality data for these cohorts. Therefore, to be consistence, we utilized 1:4 matching for all three cohort assessments, and then conducted conditional logistic regression analyses for all the study outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the overall study population, are reported as mean (95% confidence interval) or counts (percentage). T-tests for continuous covariates and chi-square tests for categorical covariates were conducted between the anticoagulant group and control group for each cohort. Multivariate binary logistic regression models, adjusted for covariates ascertained prior to the initial COVID-19 positive test, were used to compare various outcomes between those in the anticoagulation group and those in the control group. The unadjusted logistic regression model is summarized in eTable 1. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are reported for those in the overall cohort and those in the hospitalized cohort. Effect modification for the composite MSOC outcomes was conducted for various covariates as well. All statistical tests were two sided, where a p < 0.05 or a 95% confidence interval that did not cross 1.0 was considered statistically. No imputation was conducted. All analyses were done using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participants

Of the 48,066 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, we identified 879 (1.8%) patients who received therapeutic AC prior to COVID-19 diagnosis. Among the subset of 9,681 (20.1%) patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in this population, the proportion receiving therapeutic AC was 329 (3.5%; Fig. 1). Out-patient pharmacological agents used for therapeutic AC included apixaban (53%), rivaroxaban (24%), warfarin (14%), dabigatran (9%), Enoxaparin (0.2%).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographics including cardiovascular risk factors among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. The AC cohort had more comorbidities than the control group. Most notably the AC cohort had 41.2% vs 16.0% chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 43.9% vs 10% congestive heart failure (CHF), and 46.9% vs 15.3% coronary artery disease (CAD). The relative prevalence of comorbidities increased in the hospitalized versus non-hospitalized patients, including COPD (2.2-fold), CHF (3.2-fold), MI (3.3-fold), and CKD (3.3-fold). As expected, the prevalence of a prior history of thrombotic complications was higher in the AC cohort (DVT 18.0% vs 2.6%, PE 12.5% vs 1.3%), with relatively higher proportions noted in the patients who were hospitalized (DVT 2.9-fold and PE 3.3-fold).

In-hospital outcomes

Among patients contracted COVID-19 and who were hospitalized, we next evaluated their 30-day follow-up period outcomes (Table 2). There was an equivalent incidence of ICU admission (24.9% vs 23.6%, p = 0.74), as well as ICU length of stay (8.5 [4.5, 15.5] vs 9 [5.0, 15.5] days, p = 0.09) between the AC and control cohorts. Likewise, between the two cohorts there was an equivalent incidence of death during the hospitalization (10.6% vs 8.8%, p = 0.24), and death during the ICU stay (11.2% vs 10.2%, p = 0.55), despite the higher cardiovascular comorbidities in the AC cohort.

Risk of adverse events in propensity-matched groups

Table 3 summarizes risk for adverse events in the propensity matched cohorts of the AC and control patients. There was a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality in patients who received AC (aOR 0.67, 95% CI [0.46 – 0.99], p = 0.04). However, no difference was observed in the incidence of death after ICU admission (aOR 0.93, 95% CI [0.64 – 1.37], p = 0.72), stroke (aOR 1.12, 95% CI [0.79 – 1.59], p = 0.52), and limb ischemia (aOR 1.09, 95% CI [0.30 – 3.91], p = 0.89). Interestingly, there was a higher incidence of GI bleeding in the AC cohort (aOR 4.0, 95% CI [1.16 – 13.82], p = 0.02).

Discussion

Our study investigated whether continuous therapeutic AC decreased the risk of MOSC, ICU admission and in-hospital mortality in patients infected with COVID-19 during the early phase of the pandemic in the US. In the study cohort, the rate of in-hospital mortality was lower in the AC group compared to the control group, despite a higher incidence of GI bleeding. However, the rate of MOSC and ICU admission were similar between the two groups.

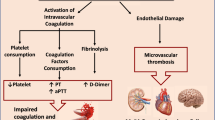

Several studies reported an increased risk of hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 positive patients [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In a meta-analysis of 91 studies evaluating 35,017 COVID-19 patients, Mansory et al. found the overall incidence of VTE events in all hospitalized and ICU patients was 12.8 and 24.1% respectively [22]. Reports showed hyper-thrombotic laboratory changes (e.g., d-dimer) in COVID-19 patients, and these changes are observed to be negative independent predictors of end-organ-damage and death [1, 23,24,25]. In addition, critically-ill COVID-19 patients manifest with a wide range of clinical symptoms that include interstitial pulmonary edema, ST elevation myocardial infarction, brainstem infarcts, gastro-intestinal mucosal bleeding, acute kidney failure, liver dysfunction, and skin petechial rashes [7, 26,27,28,29,30]. The mechanism by which COVID-19 viremia and cytokines induce thrombosis and inflammation is still not fully understood. However, some have postulated that hypercoagulability and MSOC in patients with COVID-19 results from a sequence of events that first starts with endothelial cell dysfunction and excess thrombin generation and fibrinolysis shutdown [31, 32]. Next hypoxia associated with severe COVID-19 can lead to further thrombosis via activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-dependent signaling pathway [33]. Lastly, immobilization during critically-ill states, can lead to blood flow stasis and higher incidence of in situ thrombosis.

Limited studies to date have assessed outcomes of therapeutic AC in patients with COVID-19, and the few that have provide contradictory findings. Early observational studies and a meta-analysis reported no difference in mortality in patients with COVID-19 who received AC therapy relative to those who did not receive AC, but these studies suffered from small sample sizes, heterogenous patient populations, and unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria [14, 34, 35]. In a recent meta-analysis of 11 studies investigating the impact of AC on mortality in a cohort of 20,748 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, AC therapy was found to be associated with a lower rate of in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 (RR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.52 – 0.93, p = 0.01) [36]. A large observational study including 4,389 patients from New York, demonstrated that therapeutic AC was associated with a 47% reduction in the risk of in-hospital mortality (aHR = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.45—0.62; p < 0.001) and 31% reduction in the intubation rate (aHR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.51—0.94; p = 0.02) compared with no AC [37]. In addition, Paranjpe et al. showed longer duration of AC treatment reduced the risk of in-hospital mortality (aHR of 0.86 per day; 95% CI: 0.82 – 0.89; p < 0.001) [38]. On the other hand, AC was not shown to reduce the incidence or severity of MSOC such as acute kidney injury [13].

In the present study, patients who were on a continuous prescription of therapeutically-dosed AC therapy for at least 90 days prior to their initial COVID-19 positive test, demonstrated reduced risk of in-hospital mortality when compared to control patients (aOR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.46 – 0.99, p = 0.04). Interestingly, our study observed that COVID-19 positive patients who received AC and had higher cardiovascular co-morbidities, actually had an equivalent incidence of MOSC. However, the potential benefits of AC in this higher risk population needs to be weighed against the risk of bleeding. Our study observed that AC therapy was associated with a higher incidence of GI bleeding, which is consistent with prior literature [24]. As treatment protocols continue to evolve for patients afflicted with COVID-19, personalized assessments of the risks and benefits of AC therapy should be tailored to meet the most favorable anticipated outcomes.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with certain limitations. First, the associations explored were retrospective in nature and as such can include inherent biases associated with the study design, and method of data extraction and analysis. Second, there are factors that were not included in our propensity score matching that could also potentially impact mortality and morbidity. One such risk factor is smoking status, which was not discernable in the CDW. Third, within our study cohort we were unable to determine the primary cause of death for patients with COVID-19 during the early phase of the pandemic, which we found was often not clearly defined in the patient’s medical record. Lastly, our study does not include information about inpatient AC regimens, and whether patients who contracted COVID19 were maintained on fully therapeutic AC during their hospital and/or ICU courses.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrates that among U.S. veterans afflicted by COVID-19, chronic AC therapy reduced the risk of in-hospital death. However, AC therapy did not ameliorate the risk of MOSC. These findings suggest that MOSC in patients with COVID-19 are unlikely to be mainly determined by the patient’s pro-thrombotic state. Randomized control trials are needed to further evaluate the effectiveness of AC in preventing COVID-19-related MOSC, particularly in later and ongoing stages of this evolving viral illness.

Availability of data and materials

De-identified datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- AC:

-

Anti-Coagulation Therapy

- MOSC:

-

Multi-Organ System Complications

- VA:

-

Veteran Affairs

- CDW:

-

Corporate Data Warehouse

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- HPL:

-

Hyperlipidemia

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive Heart Failure

- CAD:

-

Coronary Artery Disease

- MI:

-

Myocardial Infarction

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- PAD:

-

Peripheral Arterial Disease

- CAS:

-

Carotid Artery Stenosis

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- AVR/MVR:

-

Aortic Valve Replacement / Mitral Valve Repair

- DVT:

-

Deep Vein Thrombosis

- PE:

-

Pulmonary Embolism

- VTE:

-

Venous Thromboembolism

References

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–7.

Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033–40.

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20.

Li X, Guan B, Su T, Liu W, Chen M, Bin Waleed K, et al. Impact of cardiovascular disease and cardiac injury on in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2020;106(15):1142–7.

Khan MMA, Khan MN, Mustagir G, Rana J, Islam MS, Kabir MI. Effects of underlying morbidities on the occurrence of deaths in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2020;10(2):1–14.

Nandy K, Salunke A, Pathak SK, Pandey A, Doctor C, Puj K, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of various comorbidities on serious events. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):1017–25.

Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan. China. 2020;5(7):802–10.

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA cardiology. 2020;5(7):811–8.

Roshdy A, Zaher S, Fayed H, Coghlan JG. COVID-19 and the heart: a systematic review of cardiac autopsies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;7:626975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.626975.

Angus DC, Berry S, Lewis RJ, Al-Beidh F, Arabi Y, van Bentum-Puijk W, et al. The REMAP-CAP (Randomized Embedded Multifactorial Adaptive Platform for Community-acquired Pneumonia) Study. Rationale and design. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):879–91.

Houston BL, Lawler PR, Goligher EC, Farkouh ME, Bradbury C, Carrier M, et al. Anti-Thrombotic Therapy to Ameliorate Complications of COVID-19 (ATTACC): Study design and methodology for an international, adaptive Bayesian randomized controlled trial. Clin Trials. 2020;5:491–500.

Ec G, Ca B, Bj M, Pr L, Js B, Mn G, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with Heparin in critically Ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777–89.

Parker K, Hamilton P, Hanumapura P, Castelino L, Murphy M, Challiner R, et al. Chronic anticoagulation is not associated with a reduced risk of acute kidney injury in hospitalised Covid-19 patients. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):1–9.

Tremblay D, Van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Thibaud S, Kessler A, Venugopal S, et al. Impact of anticoagulation prior to COVID-19 infection: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Blood. 2020;136(1):144–7.

Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Factors influencing the optimal control-to-case ratio in matched case- control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(2):195–7.

Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–4.

Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1.

Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, Foppen M, Vlaar AP, Müller MCA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995–2002.

Wu C, Liu Y, Cai X, Zhang W, Li Y, Fu C. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in critically Ill patients with Coronavirus disease 2019: a meta-analysis. Front Med. 2021;8:603558 Frontiers Media SA.

Bilaloglu S, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Jones S, Iturrate E, Hochman J, Berger JS. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York city health system. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799–801.

Kollias A, Kyriakoulis KG, Lagou S, Kontopantelis E, Stergiou GS, Syrigos K. Venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med (United Kingdom). 2021;26(4):415–25.

Mansory EM, Srigunapalan S, Lazo-Langner A. Venous thromboembolism in hospitalized critical and noncritical COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. TH Open. 2021;05(03):e286–94.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62.

Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, Carlson JCT, Fogerty AE, Waheed A, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489–500.

Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13.

Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically Ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–4.

Jin X, Lian JS, Hu JH, Gao J, Zheng L, Zhang YM, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69(6):1002–9.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan. China JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–9.

Yang X, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID19 in Wuhan China. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81.

Levi M, van der Poll T. Coagulation and sepsis. Thromb Res. 2017;149:38–44.

Schmitt FCF, Manolov V, Morgenstern J, Fleming T, Heitmeier S, Uhle F, et al. Acute fibrinolysis shutdown occurs early in septic shock and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality: results of an observational pilot study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):19. Published 2019 Jan 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0499-6.

Gupta N, Zhao YY, Evans CE. The stimulation of thrombosis by hypoxia. Thromb Res. 2019;181:77–83.

Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–9.

Abdel-Maboud M, Menshawy A, Elgebaly A, Bahbah EI, El Ashal G, Negida A. Should we consider heparin prophylaxis in COVID-19 patients? a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51(3):1.

Jiang L, Li Y, Du H, Qin Z, Su B. Effect of anticoagulant administration on the mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2021;8(August):1–10.

Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, Chang HL, Moreno PR, Pujadas E, et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815–26.

Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak AJ, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:122–4 Elsevier.

Acknowledgements

The study investigators would like to thank the St. Louis Veterans Affairs research office staff, including Mrs. Erin Olson, Mr. Todd Kliche, and Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly for diligent support throughout the course of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Veterans Affairs Clinical Research and Development (VA CSRD) COVID-19 rapid funding mechanism (COVID-19–8900-13; MAZ). This work was also supported by grants from NIH/NHLBI R01HL153436 (MAZ), R01HL150891 (MAZ), R01HL153262 (MAZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MAZ. Methodology: AG, SL, YY, MAZ. Investigation: MSZ, AG, SL, KCM, MAZ. Data Collection: AG, KCM. Supervision: YY, MAZ. Writing—original draft: MSZ, MJ, AG, SL, QL, YY, MAZ. Writing—review & editing: MSZ, MJ, AG, SL, QL, YY, MAZ. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

eTable 1. Unadjusted logistic regression model of propensity matched analysis of COVID-19 associated MOSC between AC and Control groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaghloul, M.S., Jammeh, M., Gibson, A. et al. Chronic anti-coagulation therapy reduced mortality in patients with high cardiovascular risk early in COVID-19 pandemic. Thrombosis J 21, 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-023-00460-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-023-00460-z