Abstract

Background

To date, no study has explored the association between androgen levels and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels in Chinese men. We aimed to investigate the relationship between 25(OH)D levels and total and free testosterone (T), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), estradiol, and hypogonadism in Chinese men.

Methods

Our data, which were based on the population, were collected from 16 sites in East China. There were 2,854 men enrolled in the study, with a mean (SD) age of 53.0 (13.5) years. Hypogonadism was defined as total T <11.3 nmol/L or free T <22.56 pmol/L. The 25(OH)D, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, total T, estradiol and SHBG were measured using chemiluminescence and free T by enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay. The associations between 25(OH)D and reproductive hormones and hypogonadism were analyzed using linear regression and binary logistic regression analyses, respectively.

Results

A total of 713 (25.0 %) men had hypogonadism with significantly lower 25(OH)D levels but greater BMI and HOMA-IR. Using linear regression, after fully adjusting for age, residence area, economic status, smoking, BMI, HOMA-IR, diabetes and systolic pressure, 25(OH)D was associated with total T and estradiol (P < 0.05). In the logistic regression analyses, increased quartiles of 25(OH)D were associated with significantly decreased odds ratios of hypogonadism (P for trend <0.01). This association, which was considerably attenuated by BMI and HOMA-IR, persisted in the fully adjusted model (P for trend <0.01) in which for the lowest compared with the highest quartile of 25(OH)D, the odds ratio of hypogonadism was 1.50 (95 % CI, 1.14, 1.97).

Conclusions

A lower vitamin D level was associated with a higher prevalence of hypogonadism in Chinese men. This association might, in part, be explained by adiposity and insulin resistance and warrants additional investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone/vitamin that is present in certain foods and may be generated by ultraviolet-B in the skin. Vitamin D is hydroxylated in the liver to 25-hydroxy-vitamin D (25(OH)D), the primary form measured to determine vitamin D status, and can be further hydroxylated to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D [1]. The classic picture of vitamin D function is the maintenance of bone health and calcium/phosphorous metabolism [2]. However, epidemiological studies have suggested the impact of a pandemic of vitamin D deficiency on non-skeletal functions, including certain cancers, autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus, neurocognitive disorders, and mortality [3].

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is present in the testis [4], pituitary gland [5] and hypothalamus [6]. Vitamin D is likely involved in the regulation of gonadal function. Regarding the association between vitamin D and reproduction, replete vitamin D stores predicted reproductive success after in vitro fertilization [7], although excess vitamin levels might have a detrimental impact on the in vitro fertilization outcome [8]. In the USA and Europe, several cross-sectional studies have detected that serum testosterone (T) levels and 25(OH)D levels were positively associated in men [1, 9, 10] and revealed a concordant seasonal variation [1], whereas another study observed no concordant seasonal variation [10]. Therefore, the association of vitamin D with androgens and gonadal function in men has not been fully clarified and has not been reported in the general Chinese population.

We performed a large investigation in 2014, which is referred to as Survey on Prevalence in East China for Metabolic Diseases and Risk Factors (SPECT-China). Using the data from the study, we aimed to determine whether 25(OH)D was associated with the reproductive hormones of the pituitary-testis axis and hypogonadism that was based on total or free T. To the best of our knowledge, the current analyses are the first to focus on several likely explanatory factors contributing to the relationship of 25(OH)D and hypogonadism, including adiposity, insulin resistance and other metabolic factors.

Methods

Study population

SPECT-China is a population-based cross-sectional survey on the prevalence of metabolic diseases and risk factors in East China from February to June 2014. The registration number is ChiCTR-ECS-14005052 (www.chictr.org). We used a stratified cluster sampling method. The first sampling level was based on rural and urban areas and the second sampling level was based on an area’s economic development. This study was performed in Shanghai, Jiangxi Province and Zhejiang Province (three sites in urban areas of Shanghai, one site in an urban area of Jiangxi Province, three sites in rural areas in Shanghai, three sites in rural areas in Zhejiang and six sites in rural areas in Jiangxi Province) [11]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: adults aged 18 years and older; Chinese citizens; and living in their current residences for 6 months or longer. Those who had severe communication problems or acute illnesses or were unwilling to participate were excluded from the study.

A total of 7200 people participated in this investigation. The participants who had missing laboratory results (n =183) and missing questionnaire data (n =112) and were younger than 18 years of age (n =6) were excluded from the study; a total of 6,899 subjects were enrolled in the SPECT-China study [11]. Among them, there were 2940 men who did not receive vitamin D and testosterone supplementation. Men with missing values of 25(OH)D (n =1), total testosterone (n =7) and free testosterone (n =78) were excluded from the study. Finally, this study included a total number of 2854 men with a mean (SD) age of 53 (13) years. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (approval number 2013 (86)). The research was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the participants provided written informed consent before data collection.

Measurements

In every site, the same trained staff group completed the questionnaire including information on demographic characteristics, medical history and lifestyle risk factors, and they collected anthropometric data. Current smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and currently smoking cigarettes [12]. Body weight, height, and blood pressure were measured using standard methods, as previously described [12]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

The participants fasted for 8 h before the study. Fasting blood samples were drawn between 0700 h and 1000 h. The blood samples for the plasma glucose test were collected in vacuum tubes with anticoagulant sodium fluoride and centrifuged on the spot within 1 h after collection. The blood samples were stored at −20 °C and were shipped by air in dry ice within 2 to 4 h of collection to a central laboratory, which is certified by the College of American Pathologists. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was assessed using high-performance liquid chromatography (MQ-2000PT, China). The plasma glucose was measured using Beckman Coulter AU680 (Germany). Insulin was detected by chemiluminescence (Abbott i2000 SR, USA). The 25(OH)D, total T, estradiol (E2), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) were measured using the immulite 2000 platform chemiluminescence immunoassays (Siemens, Germany) and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) by electrochemiluminescence (Roche Cobas E601, Switzerland). Free T was detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bio-Tek ELx808, USA). The minimal detectable limit for hormones was as follows: 0.7 nmol/L (total T), 73.4 pmol/L (E2), and 0.1 IU/L (FSH and LH). The inter-assay coefficients of variation were as follows: 15 % (free T), 6.6 % (total T), 7.5 % (E2), 7 % (SHBG), 4.5 % (FSH) and 6.0 % (LH). The intra-assay coefficients of variation were as follows: 15 % (free T), 5.7 % (total T), 7 % (SHBG), 6.2 % (E2), 3.8 % (FSH) and 4.9 % (LH). Insulin resistance was estimated using the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR) index: [fasting insulin (mIU/L) × fasting glucose (mmol/L)]/22.5.

Definition of variables and outcomes

Hypogonadism was defined as total T <11.3 nmol/L [13] or free T <22.56 pmol/L [14] in men. Based on the American Diabetes Association 2014 criteria, diabetes was defined as a previous diagnosis by healthcare professionals, fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥6.5 %. We considered the residence area as a covariate because in China the prevalence of hypogonadism in rural and urban areas may be different [15]. The economic development status was measured by the average gross domestic product per capita of the entire nation (6807 US dollars, from the World Bank) in 2013 as the cutoff point for each site.

Statistical analysis

We performed survey analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All of the analyses were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All reported P values were 2-sided. The general characteristics are summarized as the mean (SD) values for continuous variables or as a number with proportion for categorical variables. To test for differences in characteristics between the participants with and without hypogonadism, and among 25(OH)D quartiles, Kruskal-Wallis and one-way ANOVA were used for non-normally and normally distributed continuous data, respectively, and the Pearson χ 2 test was used for categorical variables. The missing values of total T (n = 3) and E2 (n = 779) under the minimal detectable limit were replaced by the mean values that were 0.35 nmol/L and 36.7 pmol/L between 0 and the minimal detectable limit.

The association of 25(OH)D (dependent variable) with total T, free T, E2, SHBG, FSH and LH (independent variables) was assessed using linear regression. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, residence area, economic development and current smoker. Model 3 included terms for model 2, BMI, log (HOMA-IR), diabetes and systolic pressure. Because free T, SHBG, FSH, LH and HOMA-IR were non-normally distributed, they were transformed by natural logarithm. The results were expressed as unstandardized coefficients (B) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs).

The 25(OH)D was divided into quartiles, with the first quartile representing the lowest one and the fourth quartile representing the highest. Odds ratio (OR) and 95 % CI were calculated using logistic regression to determine the risk of hypogonadism for each quartile of 25(OH)D, with the highest quartile as the reference. Model 1 was adjusted for age, residence area, economic status and current smoker. Model 2 included terms for model 1, BMI and HOMA-IR. Model 3 included terms for model 2, diabetes and systolic pressure.

We tested the interaction effect between 25(OH)D and residence area, economic status, HbA1c, BMI and HOMA-IR by adding a multiplicative factor in the logistic regression model.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

General demographic and laboratory characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Seven hundred thirteen (25.0 %) participants had hypogonadism. Among these characteristics, 501 men were diagnosed with hypogonadism by total T, 334 men were diagnosed by free T and 122 men were diagnosed by both total and free T. Compared to men without hypogonadism, the men with hypogonadism were older and had significantly lower 25(OH)D levels, higher fasting insulin levels, HOMA-IR, BMI and systolic pressure as well as a higher prevalence of diabetes. With regard to hormones in the pituitary-testis axis, the men with hypogonadism had significantly lower total T, free T, E2, SHBG and higher FSH levels.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study population according to serum 25(OH)D quartiles. The quartile ranges of 25(OH)D were ≤35.36 nmol/L, 35.37-41.32 nmol/L, 41.33-48.81 nmol/L and ≥48.82 nmol/L. Compared with men in the highest quartile, the men in the lowest quartile were younger and were more likely to live in an urban area and a rapid economic development area; however, they had a higher prevalence of hypogonadism and diabetes. These men also had significantly lower total T, E2, SHBG, FSH and LH levels but higher free T levels.

Association of 25(OH)D with reproductive hormones

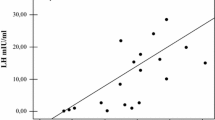

Table 3 summarizes the results of the linear regression models studying the association of 25(OH)D with total T, free T, E2, SHBG, LH and FSH. In the unadjusted models, the higher levels of 25(OH)D were associated with lower log (free T) (= − 0.002), and higher total T (B = 0.056), E2 (B = 0.866), log SHBG (B = 0.004), log LH (B = 0.004) and log FSH (B = 0.005) (all P < 0.001). After adjustment for age, residence area, economic status and current smoker, the association of 25(OH)D with log (free T) weakened further to the extent that it was no longer significant. After additional adjustments for BMI, HOMA-IR, diabetes and systolic pressure, only total T (B = 0.023) and E2 (B = 0.238) were still associated with 25(OH)D (both P < 0.05).

Association of 25(OH)D with hypogonadism

Table 4 demonstrates the results of the binary logistic regression measuring the association of 25(OH)D status with hypogonadism. In all of the models, the odds ratios for hypogonadism decreased across 25(OH)D quartiles (all P for trend <0.01). Compared with men in the highest quartile of 25(OH)D (Table 4, model 1), the odds ratio of hypogonadism in men in the lowest quartile of 25(OH)D were 1.54 (95 % CI, 1.19, 2.01; P < 0.01). After adjustments for BMI and HOMA-IR, the association was so weakened (Table 4, model 2) that it was no longer significant in Q2. Additional adjustment for diabetes and systolic blood pressure did not weaken this association (Table 4, model 3). No interaction was observed between 25(OH)D, and diabetes, BMI and HOMA-IR.

Discussion

In this population-based study of middle-aged and older Chinese men, we observed that lower 25(OH)D level was significantly associated with lower total T, E2, SHBG, LH and FSH levels after adjusting for age, residence area, economic status and current smoker. Additional adjustments for BMI, HOMA-IR, diabetes and systolic pressure revealed that total T and E2 were still associated with 25(OH)D. The fully adjusted odds ratio of hypogonadism increased by 50 % for the lowest quartile compared with the highest quartile of 25(OH)D. Adiposity and insulin resistance may, in part, explain this association. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to detect the association between 25(OH)D status and hypogonadism in Chinese men and confirms that this relationship is present in a large population.

Vitamin D deficiency, which affects not only the musculoskeletal system but also a number of acute and chronic diseases, is currently a pandemic health problem. In 1711 healthy Caucasian adults, the mean serum vitamin D concentration was 64.4 nmol/L in men [16]. In 136 healthy Japanese males, the median 25(OH)D concentration was 36.5 nmol/L and approximately 75 % of the subjects had 25(OH)D-deficiency (25(OH)D <50 nmol/L) [17]. In our participants, the fourth quartile of 25(OH)D was 48.82 nmol/L, so at least 75 % had suboptimal 25(OH)D. Interestingly, serum 25(OH)D was higher in older men than in younger men. This finding may be due to more indoor and sedentary activities in the young, whereas the older, retired men may engage in more outdoor activities that result in more sun exposure; this result warrants additional investigation.

Our results demonstrating an association of vitamin D status and testosterone in men are also consistent with outcomes in animal studies. VDR knockout mutant mice showed gonadal insufficiencies. High LH and FSH levels in the male mice indicated hypergonadotropic hypogonadism [18]. Another mouse study reported a tendency towards low testosterone/LH ratio and Leydig cell hyperplasia in VDR null mice [19]. The serum testosterone levels could increase to normal values in vitamin D-deficient rats replete with vitamin D [20]. However, controversy exists regarding to what extent vitamin D is important for sex hormone production. Blomberg Jensen et al. found that testosterone and LH serum levels were not significantly different between wildtype and VDRnull mice [19]. Additionally, vitamin D may also regulate reproductive function. VDR knockout mice had decreased sperm count, reduced sperm motility, and histological abnormality of the testis [18]. Pilz et al. [21] reported that vitamin D supplementation increases testosterone levels in non-diabetic subjects, although Jorde et al. [22] could not detect an effect of vitamin D supplements on serum testosterone concentrations in healthy men.

Our results are consistent with three previous population-based reports [1, 10, 14]. The data from the European Male Ageing Study [9] indicated that 25(OH)D is positively associated with total T. However, after adjusting for health and lifestyle factors, no significant associations were observed. This study recruited non-institutionalized, primarily Caucasian men, and the data may, therefore, not be generalizable to other groups. The association of 25(OH)D with free T varied [1, 9, 10, 14]. Because of the strong inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of free T measurements, the associations of 25(OH)D with free T should be viewed with caution [10].

In our study, hypogonadism was defined as total T <11.3 nmol/L or free T < 22.56 pmol/L, and the prevalence of hypogonadism was 25.0 % among our participants with a mean age of 53 years. In the Hypogonadism in Males study in the USA, the prevalence of hypogonadism was 38.7 % in men aged ≥45 years [23] and in Taiwanese men aged >40 years; 24.1 % had androgen deficiency [24], both of which were based on total T. Our prevalence seemed to be comparable with that observed in Taiwanese men. Such a high prevalence of hypogonadism was found to be associated with pandemic vitamin D deficiency in our study. Our results included the evidence from a new ethnic group reported in previous studies [1, 9, 10, 14]. We observed that adjustments for BMI and HOMA-IR attenuated the association between vitamin D and hypogonadism, indicating that this association was in part explained by adiposity and insulin resistance. The association between obesity and hypogonadism has been well researched [25]. Previous studies have reported that obesity is associated with low serum 25(OH)D levels [26]. Vitamin D may regulate adipose tissue [27]. VDR is observed in human adipocytes [28], and vitamin D deficiency is capable of up-regulating parathyroid hormone, thereby increasing free intracellular calcium in adipocytes, which blunts the lipolytic response to catecholamines and enhances lipogenesis [29]. Thus, this association may, in part, be mediated through adiposity.

Our study had several strengths. First, regarding the significance, this study is the first to detect the association between 25(OH)D status and hypogonadism in general Chinese men, the largest population group in the world, thereby adding new evidence to previous research. Second, this study has strong quality control; the anthropometric measurements and questionnaires were all completed by the same trained research group, and all of the biomedical measurements were performed in one laboratory certified by the College of American Pathologists. Third, our results are more reflective because the SPECT-China study was performed in a general population as opposed to a clinic-based population. However, our study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot draw a causal relationship between 25(OH)D status and hypogonadism. Second, this study recruited primarily Han Chinese men and the data cannot be generalizable to other ethnic groups. Third, we measured reproductive hormones and vitamin D once, indicating that we could not perform the seasonal variation analysis.

Conclusions

Vitamin D deficiency is pandemic in Chinese men. Lower vitamin D levels were associated with a higher prevalence of hypogonadism in Chinese men. This association was, in part, explained by adiposity and insulin resistance, which warrants additional investigation.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D:

-

25-hydroxy-vitamin D

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SHBG:

-

Sex hormone binding globulin

- VDR:

-

Vitamin D receptor

References

Wehr E, Pilz S, Boehm BO, März W, Obermayer-Pietsch B. Association of vitamin D status with serum androgen levels in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:243–8.

Holick MF. Vitamin D, deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–81.

Hossein-nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:720–55.

Blomberg Jensen M, Nielsen JE, Jørgensen A, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Kristensen DM, Jørgensen N, et al. Vitamin D receptor and vitamin D metabolizing enzymes are expressed in the human male reproductive tract. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1303–11.

Pérez-Fernandez R, Alonso M, Segura C, Muñoz I, García-Caballero T, Diguez C. Vitamin D receptor gene expression in human pituitary gland. Life Sci. 1997;60:35–42.

Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29:21–30.

Ozkan S, Jindal S, Greenseid K, Shu J, Zeitlian G, Hickmon C, et al. Replete vitamin D stores predict reproductive success following in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1314–9.

Anifandis GM, Dafopoulos K, Messini CI, Chalvatzas N, Liakos N, Pournaras S, et al. Prognostic value of follicular fluid 25-OH vitamin D and glucose levels in the IVF outcome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:91.

Lee DM, Tajar A, Pye SR, Boonen S, Vanderschueren D, Bouillon R, et al. Association of hypogonadism with vitamin D status: the European Male Ageing Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:77–85.

Nimptsch K, Platz EA, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Association between plasma 25-OH vitamin D and testosterone levels in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:106–12.

Wang N, Kuang L, Han B, Li Q, Chen Y, Zhu C, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone associates with prediabetes and diabetes in postmenopausal women. Acta Diabetol. 2015; doi:10.1007/s00592-015-0769-1.

Xu Y, Wang L, He J, Bi Y, Li M, Wang T. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA. 2013;310:948–59.

Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:724–31.

Tak YJ, Lee JG, Kim YJ, Park NC, Kim SS, Lee S, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and testosterone deficiency in middle-aged Korean men: a cross-sectional study. Asian J Androl. 2015;17:324–8.

Wu M, Li JH, Yu XH, Liang GQ, Li P, Liu ZY, et al. Late-onset hypogonadism among old and middle-aged males in a rural community of Zhejiang Province. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2013;19:522–6.

Gupta AK, Brashear MM, Johnson WD. Prediabetes and prehypertension in healthy adults are associated with low vitamin D levels. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:658–60.

Sun X, Cao ZB, Tanisawa K, Ito T, Oshima S, Ishimi Y, et al. Associations between the Serum 25(OH)D Concentration and Lipid Profiles in Japanese Men. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:355–62.

Kinuta K, Tanaka H, Moriwake T, Aya K, Kato S, Seino Y. Vitamin D is an important factor in estrogen biosynthesis of both female and male gonads. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1317–24.

Blomberg Jensen M, Lieben L, Nielsen JE, Willems A, Jørgensen A, Juul A, et al. Characterization of the testicular, epididymal and endocrine phenotypes in the Leuven Vdr-deficient mouse model: targeting estrogen signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;377:93–102.

Sonnenberg J, Luine VN, Krey LC, Christakos S. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment results in increased choline acetyltransferase activity in specific brain nuclei. Endocrinology. 1986;118:1433–9.

Pilz S, Frisch S, Koertke H, Kuhn J, Dreier J, Obermayer-Pietsch B, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on testosterone levels in men. Horm Metab Res. 2011;43:223–5.

Jorde R, Grimnes G, Hutchinson MS, Kjærgaard M, Kamycheva E, Svartberg J. Supplementation with vitamin D does not increase serum testosterone levels in healthy males. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45:675–81.

Mulligan T, Frick MF, Zuraw QC, Stemhagen A, McWhirter C. Prevalence of hypogonadism in males aged at least 45 years: the HIM study. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:762–9.

Liu CC, Wu WJ, Lee YC, Wang CJ, Ke HL, Li WM, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for androgen deficiency in aging Taiwanese men. J Sex Med. 2009;6:936–46.

Zarotsky V, Huang MY, Carman W, Morgentaler A, Singhal PK, Coffin D, et al. Systematic literature review of the risk factors, comorbidities, and consequences of hypogonadism in men. Andrology. 2014;2:819–34.

González-Molero I, Rojo-Martínez G, Morcillo S, Gutierrez C, Rubio E, Pérez-Valero V, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and incidence of obesity: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:680–2.

Cipriani C, Pepe J, Piemonte S, Colangelo L, Cilli M, Minisola S. Vitamin d and its relationship with obesity and muscle. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:841248.

Li J, Byrne ME, Chang E, Jiang Y, Donkin SS, Buhman KK, et al. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase in adipocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;112:122–6.

McCarty MF, Thomas CA. PTH excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:535–42.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

The authors thank Chunfang Zhu, Xiaoqi Pu, Zhen Cang, Chaoxia Zhu, Meng Lu, Ying Meng, Hui Guo, and Chi Chen for collecting data and Weiping Tu, Bin Li and Ling Hu for organizing this investigation.

Language editing was performed by a distinguished professional service (http://www.aje.com/).

The authors thank all of the team members and the participants from Shanghai, Zhejiang Province and Jiangxi Province in the SPECT-China study.

This study was supported, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81270885 and 81070677); Clinical Potential Subject Construction of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (grant number 2014); the Ministry of Science and Technology in China (grant number 2012CB524906); the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant number 14495810700); and funds for outstanding academic leaders in Shanghai (grant number 12XD1403100). All of the funding sources played no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Ningjian Wang, Bing Han and Qin Li collected the data and drafted the manuscript. Ningjian Wang, Yi Chen, Yingchao Chen, Fangzhen Xia and Dongping Lin participated in the study design and performed the statistical analysis. Yingli Lu and Michael D. Jensen conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, N., Han, B., Li, Q. et al. Vitamin D is associated with testosterone and hypogonadism in Chinese men: Results from a cross-sectional SPECT-China study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 13, 74 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0068-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0068-2