Abstract

Background

Penile squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) is a highly aggressive malignancy with a poor prognosis. BRCA1/2 mutations are associated with impaired DNA double-strand break repair and are among the common mutations in penile cancer, potentially paving the way for poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitor therapy.

Case presentation

We report a 65-year-old male with PSCC who progressed to thigh metastasis at 10 months after partial penectomy. Next-generation sequencing showed that the penis primary lesion and metastatic thigh lesion harboured a BRCA2 mutation. Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy was used for treatment, and the thigh metastasis was found to involve no tumour. Progression-free survival (PFS) lasted for 8 months until the appearance of lung metastasis. Afterwards, the patient benefited from second-line therapy of olaparib with pembrolizumab and anlotinib, and his disease was stable for 9 months. The same BRCA2 was identified in the lung biopsy. Given the tumour mutation burden (TMB, 13.97 mutation/Mb), the patient received third-line therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, but PFS only lasted for 3 months, with the appearance of right frontal brain metastasis. Then, the patient was treated with radiation sequential fluzoparib therapy as fourth-line treatment, and the treatment efficacy was evaluated as PR. Currently, this patient is still alive.

Conclusions

This is the first report of penile cancer with BRCA2 mutation, receiving a combination treatment with olaparib and experiencing a benefit for 9 months. This case underscores the pivotal role of BRCA2 in influencing treatment response in PSCC, providing valuable insights into the application of targeted therapies in managing recurrent PSCC with BRCA2 alterations. This elucidation establishes a crucial foundation for further research and clinical considerations in similar cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Penile cancer is a rare disease, constituting less than 1% of male malignancies. Almost 95% of penile cancers are penile squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) [1]. Unfortunately, patients with metastatic PSCC have poor prognosis, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of only 5–10% [2]. The first option for metastatic PSCC remains platinum-based chemotherapy, but the response rate of 15–55% is disappointing [3]. After unsuccessful chemotherapy, recurrent cases are confronted with limited treatment options, mainly involving radiotherapy and immunotherapy. While some patients expressing EGFR may derive benefits from EGFR-targeted therapy, it is noteworthy that certain studies indicate a weak correlation between EGFR expression and treatment response [2]. Therefore, it is meaningful to explore multimodal management and potential targeted therapies.

Previous research on metastatic PSCC genomic profiling showed that TP53, CDKN2A, PIK3CA, EGFR, and BRCA2 were the frequently mutated genes. Genetic testing facilitates personalized tumour treatment. For example, PI3KA-specific inhibitor and CDK4/6 inhibitor to treat patients with PIK3CA and CDKN2A mutations in advanced breast cancer [4], deleterious mutations in DNA damage responsive (DDR) genes are frequently associated with response to PARP inhibitors and platinum chemotherapy, and BRCA1/2 are the most well-described genes in the pathway. Ali et al. reported that BRCA2 insertions/deletions were found in 10% of 20 patients with advanced PSCC [5]. Some solid tumours with BRCA2 mutation have been shown to be sensitive to chemotherapy, PARP inhibitors (PARPi), and immunotherapy [6]. However, effectiveness in penile cancer remains unclear, with no evidence reported to date.

Here, we report a rare case of a patient with metastatic PSCC and a somatic BRCA2 mutation who received multiline therapy, including disease stabilization after treatment with olaparib combined with pembrolizumab and anlotinib. This patient also responded well to chemotherapy plus immunotherapy and radiotherapy, providing new choices for metastatic PSCC treatment strategies in the future.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old man underwent partial penectomy, and postoperative pathology revealed highly to moderately differentiated stage pT2 PSCC (AJCC eighth edition TNM staging) in October 2019. The treatment history of this patient is shown in Fig. 1.

The patient did not receive any medication after the operation. In August 2020, a follow-up examination revealed a mass in the right lower limb, and the patient was admitted to Beijing Jishuitan Hospital. Then, he underwent excision of soft-tissue tumours in the thigh under intralesional anaesthesia. Postoperative pathology showed metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, with no tumour remnants on the glass surface or skin margins. And no lymph node metastasis was observed.

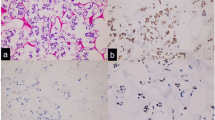

With the patient’s consent, next-generation sequencing of the PSCC tissue sample (including the penis primary lesion and the metastatic thigh lesion) was performed using the Acornmed 808-gene panel (Table 1). Somatic gene mutations for the penis primary lesion were detected, including LATS1 p.k751_A752 delinsSSCX (15.73%), BRCA2 p.S3245X (13.08%), and EGFR copy number gain (7.579X). Somatic gene mutations for the metastatic thigh lesion detected included BRCA2 p.S3245X (35.66%), EGFR copy number gain (6.632X), WT1 copy number gain (6.607X), and DNMT1 copy number gain (4.009X). The TMB for the penis primary lesion and the metastatic thigh lesion was 5.58 and 6.09 mutations/Mb, respectively. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Dako 22C3 pharmDx) showed a tumour proportion score of 5% (penis primary lesion) and < 1% (metastatic thigh lesion).

The patient was administered chemotherapy plus immunotherapy (pembrolizumab 200 mg d4; albumin paclitaxel 200 mg/100 mg d1/d5 plus cisplatin 140 mg d1) in September 2020. Eight months later, lung metastasis was detected. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed (on May 2021) multiple nodules in the dorsal segment of the lower lobe of the right lung and irregular nodules in the anterior segment of the upper lobe of the left lung, both of which were considered possible metastasis.

Considering the BRCA2 mutation, the patient was then started on olaparib plus pembrolizumab and anlotinib treatment (olaparib 300 mg (twice daily [BID]); pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks (Q3 W) and anlotinib 12 mg once a day from day 1 to 21 of a 21-day cycle) in May 2021. Several days later, his physical strength and mental status improved significantly. Follow-up CT scans after two cycles revealed that the metastasis centre was significantly reduced, and 4 months after receiving olaparib, the evaluation showed a sustained response. Due to COVID-19, the patient was not followed up until February 2022. Chest CT showed lesions in the dorsal segment of the right lower lobe and nodules in the left anterior lobe that were both increased (Fig. 2). Lung biopsy confirmed metastatic PSCC, and target sequencing detected the same BRCA2 (6.86%) as well as EGFR copy number gain (7X). The TMB was calculated as 13.97 mutation/Mb.

A Baseline CT image of lung metastases before olaparib treatment. B Chest CT image after 2 months olaparib treatment. C Chest CT image after 4 months olaparib treatment, the patient was evaluated as having stable disease. D Baseline MRI image of brain metastases before radiotherapy treatment. E MRI of brain metastases after 5 months radiation sequential fluzoparib therapy. F Chest CT after 3 months radiation therapy. G chest CT after 5 months radiation sequential fluzoparib therapy

Due to the high TMB, the patient joined a clinical trial and received dual immunotherapy (nivolumab 200 mg + ipilimumab 50 mg) in March 2022. However, he found an enlarged mass on his right forehead in May 2022. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging revealed a space-occupying cystic lesion in the right frontal lobe with a maximal diameter of 47 mm. Subsequently, the treatment plan was changed, and he underwent stereotactic brain radiosurgery (dose per fraction 300 Gy, total dose 3000 Gy). In parallel, the patient underwent stereotactic lung radiosurgery (dose per fraction 200 Gy, total dose 5000 Gy). In August 2022, after radiotherapy treatment, a chest CT scan was performed. Considering the treatment, he began receiving fluzoparib (100 mg every day) in September 2022. Follow-up chest CT scans (October 2022) showed central lesions in the dorsal segment of the lower lobe of the right lung and central nodules in the left anterior lobe that were both significantly decreased. Brain MRI revealed significant tumour reduction, and treatment effectiveness was evaluated as PR (Fig. 2). The patient continued to receive radiotherapy.

Discussion and conclusions

The prognosis of this patient before starting treatment was particularly poor, not only because his tumour harboured BRCA2 mutation and EGFR copy number gain but also because he had multiple metastases within 1 year of diagnosis. With the typical prognosis of metastatic PSCC being less than 1 year, the 2-year survival of this patient is remarkable, especially given that he is currently alive [2]. This patient may have benefited from mutation-specific therapies such as chemotherapy plus immunotherapy, olaparib, and radiotherapy.

A previous study reported cisplatin combined with ifosfamide and paclitaxel (TIP regimen) as prior treatment for metastatic penile cancer [2]. Pagliaro et al. reported 30 patients with locally advanced disease who received neoadjuvant TIP; 15 (50.0%) reached objective response, comprising 3 complete responses (CRs) and 12 partial responses (PRs). Nineteen patients (63.3%) in this group had disease progression or recurrence [7]. Currently, there is no standard second-line regimen after first-line chemotherapy failure. In a study of 17 patients who underwent ≥ 1 salvage therapy after tumour progression from the first treatment, those who were treated with a second cisplatin-based therapy had a median overall survival (OS) of 5.6 months, and those who did not receive a second cisplatin-based therapy had a median OS of 4.3 months [8].

Given the rarity of mPSCC and the high recurrence rate after conventional treatment, it is critical to explore the genomic profile of mPSCC for potential therapeutic targets. Of 20 mPSCC patients who were enrolled to analyse comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP), 10% carried BRCA2 mutations [5]. BRCA2 consists of 5 domains, which bind to DNA and interact with RAD51. Therefore, BRCA2 plays an important role in error-free repair of DNA double-strand breaks by mediating orderly assembly of RAD51 on ssDNA. Individuals with BRCA2 mutations are susceptible to breast, ovarian, and other cancer types [9]. While the genomic landscape of mPSCC has been previously reported, the therapies received by patients and their responses to treatment were not given.

BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are more responsive to chemotherapy treatments than noncarriers in breast cancer and urinary and/or ovarian cancer [10]. Recently, some studies have also shown that the immunostimulatory effects of chemotherapy can improve the efficacy of many immunotherapies because of enhanced genomic instability and immunotherapy activity [11]. and cytoplasmic dsDNA-induced DNA damage and immunogenicity have been proven to induce cell death [12]. Therefore, clinical trials have been developed to investigate the efficacy of combining chemotherapy and ICIs; for example, a significantly longer survival has been observed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with pembrolizumab co-administered with chemotherapy as the first line [13]. Thus far, few studies have applied immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) plus chemotherapy for PSCC. Li et al. reported the efficacy of immunotherapy plus chemotherapy in a patient with PSCC after recurrence. The disease progressed with multiple enlarged inguinal lymph nodes at 11 months after surgery, and immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was administered. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the multiple lymph nodes in the groyne area disappeared [14]. However, no relevant reports on immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in advanced penile SCC with BRCA mutations are available.

Here, we report the first mPSCC patient with BRCA2 mutation whose disease was stable for 9 months when receiving treatment with olaparib combined with pembrolizumab and anlotinib. BRCA2 p.S3245X was detected in the penis primary lesion, metastatic thigh lesion, and lung lesion of this patient. As with previous studies in other solid tumours, tumours with BRCA2 mutations are sensitive to treatment with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi). Olaparib is a PARPi that inhibits PARP enzymes such as PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3. PARP enzymes are critical for DNA transcription and repair [15]. Based on the results of a series of clinical trials, olaparib has been approved by the FDA as a treatment for ovarian cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer [16]. Meanwhile, the FDA has specified that the mutation status of patients should be identified before treatment. To date, several biomarkers have been confirmed to be able to indicate the sensitivity of patients to olaparib, including BRCA mutation and homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)-positive and homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene mutation. However, olaparib usage is linked to varied adverse effects, as revealed in a meta-analysis of 14 studies with 5119 cases [17]. Adverse reactions vary across different cancers. Notably, fatigue is prominent in pancreatic cancer, while ovarian cancer shows increased severity in anaemia, neutropenia, nausea, and vomiting. Breast cancer exhibits notable grade 3 or above adverse reactions with fatigue and vomiting. Furthermore, there is currently no relevant research on the side effects of olaparib in penile cancer. Therefore, using olaparib in penile cancer carries maybe certain risks. Our case is the first report of a penile cancer patient with BRCA mutation benefiting from olaparib treatment, but further research is needed to expand its applicability in the future.

BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are not only more responsive to chemotherapy and PARPi than noncarriers but are also sensitive to radiotherapy [18]. Alain Fourquet et al. reported that breast cancer patients who received radiotherapy had a major clinical response rate of 68% (13/19 tumours). This study suggests that BRCA1/2 mutations are associated with higher response rates to radiosensitivity in breast cancers. In a recent systematic review of the literature, PARPi were also efficient radiosensitizers capable of enhancing the death ratio between 1.04 and 2.87 in several tumour models [19, 20]. The reason is the synergistic effects on DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation and inhibition of proteins essential for DNA damage repair by PARPi. Radiotherapy is used for penile cancer, but few articles have reported efficient radiotherapy. In our case, the patient carried a BRCA2 mutation and received PARPi therapy after radiotherapy, and follow-up chest CT scans (October 2022) showed significant tumour shrinkage. These findings indicate that in penile cancer, cases involving BRCA mutation are sensitive to radiotherapy and/or PARPi. However, larger clinical samples may be needed to confirm this in the future.

Of note, in our case, the patient’s disease was stable at 9 months after triple therapy of olaparib with pembrolizumab and anlotinib, and the patient also benefits from radiation therapy and chemotherapy plus immunotherapy. All of these results indicate that the combination of immunotherapy and targeted therapy as well as radiation therapy were beneficial for restricting tumour progression in this patient. Therefore, to potentially increase treatment efficacy and prevent the development of disease resistance, we hypothesize that if radiation therapy is used immediately after lung metastasis, it may further improve the quality of life of patients.

In conclusion, the drugs available for treating recurrent PSCC are very limited. This is the first report of olaparib efficacy in treating PSCC with BRCA2 mutation. We report a PSCC patient with BRCA2 mutation who received olaparib combined with pembrolizumab and anlotinib, with satisfactory effects. Furthermore, posterior-line treatment options for recurrent PSCC with BRCA2 mutation were studied, and the effectiveness of chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy and radiotherapy was verified. The results suggest potential treatment options for advanced or refractory PSCC and show that genetic testing facilitates personalized tumour treatment, offering a pathway to individualized therapeutic strategies.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- PSCC:

-

Penile squamous cell carcinoma

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- TMB:

-

Tumour mutation burden

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PARPi:

-

PARP inhibitors

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- HRD:

-

Homologous recombination deficiency

- HRR:

-

Homologous recombination repair

References

Wang Y, Wang, K, Chen, Y, Zhou, J, Liang, Y, Yang, X, et al, Mutational landscape of penile squamous cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:1280–9.

Brown A, Ma Y, Danenberg K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: a report of 3 cases. Urology. 2014;83:159–65.

Cong K, Peng M, Kousholt AN, Lee WTC, Lee S, Nayak S, et al. Replication gaps are a key determinant of PARP inhibitor synthetic lethality with BRCA deficiency. Mol Cell. 2021;81:3128-44.e7.

Chahoud Jad, Gleber-Netto Frederico O, McCormick Barrett Z, Rao Priya, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in penile squamous cell carcinoma uncovers novel prognostic categorization and drug targets similar to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(9):2560–70.

Ali SM, Pal SK, Wang K, Palma NA, Sanford E, Bailey M, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of advanced penile carcinoma suggests a high frequency of clinically relevant genomic alterations. Oncologist. 2016;21:33–9.

FDA approves olaparib for adjuvant treatment of high-risk early breast cancer | FDA [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-olaparib-adjuvant-treatment-high-risk-early-breast-cancer (accessed 12.7.22).

Fourquet A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Kirova YM, Sigal-Zafrani B, Asselain B. Familial breast cancer: clinical response to induction chemotherapy or radiotherapy related to BRCA1/2 mutations status. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:127–31.

Galluzzi L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunological mechanisms underneath the efficacy of cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:895–902.

Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–92.

Holloman WK. Unraveling the mechanism of BRCA2 in homologous recombination. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:748–54.

Jacob JM, Ferry EK, Gay LM, Elvin JA, Vergilio JA, Ramkissoon S, et al. Comparative genomic profiling of refractory and metastatic penile and nonpenile cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: implications for selection of systemic therapy. J Urol. 2019;201:541–8.

Jiang M, Jia K, Wang L, Li W, Chen B, Liu Y, et al. Alterations of DNA damage response pathway: biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:2983–94.

Lesueur P, Chevalier F, Austry JB, Waissi W, Burckel H, Noël G, et al. Poly-(ADP-ribose)-polymerase inhibitors as radiosensitizers: a systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical human studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:69105–24.

Li N, Xu T, Zhou Z, Li P, Jia G, Li X. Immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for postoperative recurrent penile squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 837547.

McGregor BA, Sonpavde GP. Management of metastatic penile cancer. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021.

Pagliaro LC, Williams DL, Daliani D, Williams MB, Osai W, Kincaid M, et al. Neoadjuvant paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin chemotherapy for metastatic penile cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3851–7.

Zhou Y, Zhao S, Wu T, Zhang H. Comparison of adverse reactions caused by olaparib for different indications. Front Pharmacol. 2022Jul;13(13): 968163.

Penile cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:12.

Vallard A, Magné N, Guy JB, Espenel S, Rancoule C, Diao P, et al. Is breast-conserving therapy adequate in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers? The radiation oncologist’s point of view. Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20170657.

Wang J, Pettaway CA, Pagliaro LC. Treatment for metastatic penile cancer after first-line chemotherapy failure: analysis of response and survival outcomes. Urology. 2015;85:1104–10.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qing Zhang and Yaping Li carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript.Yanrui Zhang and Qing Zhang performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design.Yi Ding and Deng Zhiping participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. Case report of penile squamous cell carcinoma continuous treatment with BRCA2 mutation. World J Surg Onc 22, 50 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-024-03305-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-024-03305-9