Abstract

Objective

This study focused on evaluating whether high-intensity interval training (HIIT) had an effect on aerobic capacity and fatigue among patients with prostate cancer (PCa) and exploring its effect on the immune system of PCa patients.

Methods

To investigate the potential effect of HIIT on patients with prostate cancer, a meta-analysis was carried out. From January 2012 to August 2022, studies that met predefined criteria were searched in the Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO databases. Analysis of the standardized mean differences was performed using Review Manager 5.4.1 software with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

This review examined a total of 6 articles. There were 215 male patients with PCa involved, and the mean age was 64.4 years. According to the results of the meta-analysis, the HIIT group (n = 63) had greater VO2peak (P<0.01) than the control group (CON) (n = 52) (P = 0.30, I2 = 19% in the heterogeneity test; MD, 1.39 [0.50, 2.27]). Moreover, fatigue was significantly different (P<0.01) between the HIIT (n = 62) and CON (n = 61) groups (P = 0.78, I2 = 0% in the heterogeneity test; SMD, −0.52 [−0.88, −0.16]). Furthermore, among PCa patients, HIIT showed higher efficacy (P < 0.01) in decreasing PSA than the CON regimen (P=0.22, I2 = 34% in the heterogeneity test; MD, −1.13 [−1.91, −0.34]).

Conclusions

HIIT improves aerobic capacity, fatigue, and PSA levels among PCa patients but does not significantly affect IL-6 or TNF-α content. Therefore, HIIT may be a novel and potent intervention scheme for PCa patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostatic cancer (PCa) is the second most common male cancer globally [1] and is an important cause of death worldwide [2]. Treatments for PCa vary depending on the disease severity. Radiotherapy (RT) with/without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been extensively adopted in diverse risk groups in line with guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [3]. While advancements in RT have decreased cancer mortality, rehabilitative care for PCa remains to be further improved for the increasing number of cancer patients [4]. Cancer patients encounter different, unfavorable, treatment-associated adverse reactions, such as a decrease in aerobic capacity and an increase in fatigue. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is generally suggested to be aggravated in 78–89% of cases over the course of RT [5, 6], while exercises involving rehabilitative interventions can mitigate CRF [7].

Recently, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has attracted much attention because of its short duration and beneficial effects. This regimen involves short bursts of intense activity interspersed by periods of low-intensity exercise or rest. For patients with PCa, the health benefits of HIIT have been widely studied, and HIIT before or after cancer treatment has been demonstrated to markedly enhance aerobic capacity and fatigue in comparison with routine intervention [8, 9]. Typically, continuous HIIT contributes to adapting to cardiorespiratory fitness for adult cancer patients in a short period compared with moderate-intensity training [10]. The above results suggest the critical role of HIIT-induced physiological adaptations in exercise doses ≥80% HRmax [11]. Although it has been suggested that HIIT has increasing benefits for adult cancer patients, this remains a controversial opinion. Some studies [12, 13] have indicated that 8 weeks of HIIT training has no effect on aerobic capacity or fatigue in patients with PCa. Therefore, it remains unclear whether HIIT affects aerobic capacity and fatigue in patients with PCa.

This review focused on evaluating whether HIIT had an effect on the aerobic capacity and fatigue of patients with PCa and exploring its effects on the immune system among PCa patients. Our results can shed more light on the application of HIIT in treating PCa.

Methods

Protocols and registration

On August 13, 2022, our study protocols were registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42022351079). The present review was carried out in line with the PRISMA guidelines (Additional file 1).

Data sources and study selection

English biomedical databases, including Web of Science, SCOPUS, PubMed, and EBSCO, were searched between January 2012 and August 2022. Keywords for the search were utilized separately or in combination and included the following: “high-intensity intermittent,” “high-intensity interval training,” “prostate cancer,” “training,” and “exercise.” In addition, this study also manually checked reference lists in related systematic reviews and meta-analyses to identify other related articles. Additional file 2 displays more details regarding the study search procedure.

Studies were searched in the above databases by 2 reviewers independently by reading titles and abstracts. Later, data were collected from all studies, including first author, age, publication year, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, intervention duration, intervention program, equipment, and major indicators obtained at baseline and endpoint (Table 1). Corresponding authors were contacted to request any missing data via email. Additionally, any disagreement was settled by negotiation with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review adopted the following criteria to select relevant articles, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs): studies involving PCa patients aged ≥18 years; those regarding HIIT versus routine care; those reporting outcome measures such as peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), fatigue (for any measure used), PAS, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6); and those published in English. In addition, case reports, reviews, animal trials, studies without available full texts, or those with insufficient outcome data were excluded. Specifically, articles were screened via 2 steps, namely, title/abstract screening based on our preset inclusion criteria and careful reading of full texts for possibly related articles.

Assessment of quality

This study adopted the Cochrane risk bias assessment approach for evaluating the methodological quality of all enrolled articles. It evaluated the generation of random sequences, concealment of allocation, participant/personnel blinding, outcome measure blinding, selective reporting, insufficient outcome data, and additional biases involved in those articles. Each item was rated as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” Figure 1 presents detailed information on the risk of bias analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias

Each of the included studies was excluded one at a time for sensitivity analysis to analyze the stability of our meta-analysis results. A funnel plot and Egger’s test were adopted to analyze publication bias among the enrolled articles.

Statistical analysis

Related outcome variables were imported into Review Manager (Version 5.4.1, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) for meta-analysis. Continuous outcome variables were examined for all the enrolled articles. The mean difference (MD) was chosen as the effect scale index for identical test methods and units, while the standardized mean difference (SMD) was selected otherwise. Moreover, this study adopted the I2 statistic for analyzing heterogeneity among diverse articles, where I2<50% represented the absence of heterogeneity, in which case a fixed-effects model was applied. Finally, a funnel plot was drawn to check the possible bias among articles, and a forest plot was adopted to determine MD and SMD.

Results

Article eligibility

Regarding the search results of the 2 reviewers, Cohen’s kappa coefficient was 0.880. This review examined a total of 6 articles. All studies were RCTs (Fig. 2), all of which satisfied our preset eligibility criteria and mentioned baseline as well as eventual postintervention data. The selected studies were approved by the corresponding institutions. Of them, 4 and 3 evaluated VO2peak and fatigue, respectively, while two evaluated IL-6, TNF-α, and PSA (Table 1). There were 215 male patients involved, and the mean age was 64.4 years. The HIIT intervention duration ranged from 8 to 12 weeks. The intervention program of the CON group was the same as that of the HIIT group. One [16] study used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) to assess fatigue level, and two [9, 12] adopted the quality of life (QOL). Exercise-related side effects were not reported.

Sensitivity analysis

In this study, separate article exclusion, analysis model alteration, and effect size selection were utilized for sensitivity analysis. Due to the small number of included studies, only VO2peak and fatigue indicators were subject to sensitivity analysis. As a result, the meta-analysis results were not evidently altered following sensitivity analysis, indicating that the results were reliable.

Quantitative synthesis

There were 4 [9, 13,14,15] and 3 [9, 12, 16] studies comparing the efficacy of the HIIT group and CON group in terms of VO2peak (Fig. 3a) and fatigue, respectively (Fig. 3b). According to the meta-analysis results, the HIIT group (n = 63) had enhanced VO2peak (P<0.01) compared with the CON group (n = 52) (P = 0.30, I2 = 19% according to the heterogeneity test; MD, 1.39 [0.50, 2.27]). Moreover, fatigue was significantly different (P<0.01) between the HIIT (n = 62) and CON (n = 61) groups (P = 0.78, I2 = 0% according to the heterogeneity test; SMD, −0.52 [−0.88, −0.16]).

In addition, there were 2 studies [13, 14] comparing the efficacy of the HIIT group (n = 25) and CON group (n = 15) in terms of IL-6 (Fig. 4a) and TNF-α (Fig. 4b). The results showed no significant difference in IL-6 (P=0.53) or TNF-α (P=0.99) (for IL-6: P = 0.94, I2 = 0% according to the heterogeneity test; MD, 0.92 [−1.92, 3.76]; for TNF-α: P = 0.43, I2 = 0% according to the heterogeneity test; MD, −0.00 [−0.50, 0.49]). In addition, there were two studies [14, 15] comparing the efficacy of HIIT (n = 46) and CON (n = 36) on PSA (Fig. 4c). HIIT showed higher efficacy (P < 0.01) in decreasing PSA among PCa patients than CON (P=0.22, I2 = 34% according to the heterogeneity test; MD, −1.13 [−1.91, −0.34]).

Publication bias

A funnel plot was drawn to analyze publication bias among the enrolled articles. As there were few articles regarding HIIT among PCa patients, only 6 articles were enrolled in this meta-analysis. By adopting the funnel plot, the overall sample size among the enrolled articles approached the minimal requirement, which could partially indicate publication bias. Lu and colleagues [17] suggested that funnel plot analysis was feasible by the use of the small sample size. A funnel plot showing the efficacy of HIIT in terms of VO2peak and fatigue among PCa patients is displayed in Fig. 5. In addition, no evident publication bias was revealed by Egger’s test (VO2peak: P=0.83, t=0.24; fatigue: P=0.42, t=1.29). Figure 6 presents the funnel plot showing the efficacy of HIIT in terms of IL-6, TNF-α, and PSA among PCa patients.

Discussion

Although HIIT is often used in the rehabilitation treatment of cancer, few studies have applied it to PCa patients. This review mainly discusses the effect of HIIT on aerobic capacity and fatigue in PCa cases. The secondary endpoint was the effect of HIIT on immune factors among PCa patients. According to this meta-analysis, HIIT significantly improved VO2peak, fatigue, and PSA levels over the control treatment, but it did not significantly affect TNF-α or IL-6 content. This result reminded that HIIT might be a novel and potent intervention scheme for PCa patients.

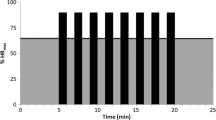

HIIT is defined as either long, repeated (45 s–4 min) bouts of rather high- but not maximal-intensity exercise or short (< 30 s) all-out sprints interspersed with periods of recovery. These varying length efforts combine to create training sessions that last a total of 5–60 min (including recovery intervals) [18]. The four distinct HIIT formats these generate are thought to be important components for inclusion in the periodization of training programs for the development of middle- to long-term physiological adaptation [8]. The exercise intensity in this study was not maximal, and the exercise time was more than 1 min. This indicates that the exercise modes in this study were the traditional HIIT mode but not sprint interval training.

Aerobic capacity is an important physiological index for PCa patients. Specifically, an increase in cardiorespiratory fitness by 3.5 mL/kg/min will reduce cancer-specific mortality by 10% and cardiovascular-related mortality by 25% [19]. Therefore, the elevated VO2peak seen in the present review might provide great benefits for cardiovascular health among PCa patients. The findings of this study are in agreement with those of a prior meta-analysis indicating the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of HIIT in enhancing VO2peak among treated adult cancer patients [10]. For male PCa patients, aerobic exercises can remarkably improve VO2peak [20], and in recent years, 12-week HIIT (8×2 min 85–95%VO2peak treadmill speed and grade, with 2-min active recovery) in the process of active surveillance can dramatically enhance VO2peak in comparison with routine care [15]. These studies support the conclusion of this review. The improvement in VO2peak by HIIT may be related to the adaptation to high physiological load. It has been suggested that HIIT activates complicated molecular interactions within the skeletal muscle to increase oxidative enzyme activities, mitochondrial biogenesis, and angiogenesis [21, 22]. As reported by Laursen and colleagues [23], activation of the AMPK-PGC1α pathway or CAMK-PGC1α has a predominant role in determining cell stimuli to aerobic adaptations, and HIIT more significantly activates AMPK-PGC1α than CAMK-PGC1α. In addition, HIIT stimulates glycogen synthesis [24]. It is possible that the peak lactate level and exhaustion time adaptively increase due to the changes in lactate generation and overload. Consequently, HIIT can effectively improve cardiorespiratory fitness among treated male patients, but such results should be investigated in large and high-quality studies.

It has been reported that exercise can more effectively compensate for fatigue in the treatment course than pharmacological intervention [25]. As confirmed in this review, HIIT better prevented fatigue deterioration than PCa patients receiving usual care. These results conformed to those of prior studies on resistance, aerobic exercise, or their combination among male PCa patients who received radiotherapy intervention [26, 27]. Their radiotherapy regimen was prostate irradiation, received as 68 to 76 Gy in 34 to 38 fractions. Likewise, additional short- (12-week) or long-term (1 year) aerobic training interventions reduce or prevent the worsening of fatigue in patients with PCa [28, 29]. A potential mechanism of exercise interventions in counteracting fatigue is improved exercise capacity [30]. According to our results, the HIIT group had remarkably improved VO2peak in comparison with the CON group. Typically, HIIT is suggested to show higher efficacy in increasing cardiorespiratory fitness than MICT for patients with cancers or cardiometabolic disorders [31, 32]. Consequently, HIIT might promote functional exercise capacity since it enhances oxygen consumption.

Recently, cytokine genetic polymorphisms were found to be related to increased inflammation, cytokine production, and possibly prostate cancer risk [33, 34]. Although these results showed that the inflammation level was not significantly different between the groups, HIIT might suppress the biochemical progression of PCa, consistent with previous results. Currently, a prostate-specific antigen is the best first-step serum marker as a screening test for PCa. It is still the most frequently used oncological marker. Numerous studies have shown that the risk of current and future prostate cancer is directly related to serum PSA [35,36,37]. Increasing PSA levels are a predictor of a greater risk of adverse pathologic features and worse disease-specific survival [38]. In addition, evidence from a randomized trial further confirmed that PSA testing reduces both metastatic disease and prostate cancer-specific mortality [39]. As reported by Kang and colleagues [15], HIIT exercise at 95% VO2peak was used for a 12-week period, thrice a week. According to their results, HIIT promoted cardiorespiratory fitness while reducing PSA velocity, PSA content, and PCa cell proliferation among male localized PCa patients receiving active surveillance. As indicated by one exploratory exercise article carried out among PCa patients receiving active surveillance, PSA content was not changed after long-term, home-based moderate-intensity exercise intervention [40]. The reason for this difference may lie in the difference in exercise intensity. In contrast, our adopted exercise program placed greater emphasis on short-term (8–12 weeks), high-intensity exercise (namely, 85–95% HRmax), which induced more physiological alterations (such as cytotoxic immunocyte mobilization and sympathetic activation) [41, 42]. Based on the above results, HIIT might be necessary for producing changes in the biochemical outcomes of PCa. The biological mechanisms of the effects of exercise on prostate cancer remain unclear. One plausible mechanism is the enhanced immunosurveillance after exercise training or even during a single bout of exercise [43, 44]. Specifically, exercise can mobilize cytotoxic natural killer cells into circulating blood and can redistribute these cells to tumor cells with assistance from exercise-induced increases in circulating norepinephrine and IL-6 [41]; this process appears to require endurance exercise at high intensity [45]. Other possible explanations include exercise-based suppression of prostate cancer progression via modulation of systemic inflammatory mediators [46], metabolic biomarkers [47], and tumor vascularization and perfusion [48]. More research in active surveillance clinical settings is necessary to identify the biophysiological associations between exercise and prostate cancer [49] and to further explore potential tumor-related biomarkers [50].

In addition, the progression of patients with PCa can be divided into early and advanced stages. Although the effect of HIIT application in different periods is unclear, according to the current research, the early use of exercise intervention may not affect the progression of prostate cancer [51]. However, the use of exercise intervention in any period can yield certain benefits, especially in the advanced stage, and the use of exercise intervention can significantly improve the quality of life, walking ability, and mortality of patients [52, 53].

However, there were still many limitations in this study. First, this study only targeted PCa patients but did not include other cancer patients. Second, since HIIT has only been applied to PCa patients in recent years (2020–2022), few studies were included. Therefore, our findings must be interpreted cautiously and should be supplemented by more studies in the future. In addition, no other forms of exercise were compared with HIIT, such as moderate-intensity continuous training or resistance training. Therefore, it was impossible to determine which form of exercise was more effective as an intervention for PCa patients. Finally, the observed indicators were not comprehensive, and changes in other inflammatory factors and anti-inflammatory factors could not be observed due to the low number of included studies. Future studies should be conducted to analyze how HIIT affects the quality of life or other physiological indicators of PCa. However, we still suggest that doctors use HIIT as a means to intervene in the non-drug treatment of prostate cancer patients after determining the exercise risk of the patient.

Conclusion

HIIT improves aerobic capacity, fatigue, and PSA levels among PCa patients but does not significantly affect IL-6 or TNF-α content. Therefore, HIIT may be a novel and potent intervention scheme for PCa patients.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available from the corresponding authors.

References

Horgan S, O’Donovan A. The impact of exercise during radiation therapy for prostate cancer on fatigue and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2018;49(2):207–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2018.02.056.

Withrow D, Pilleron S, Nikita N, et al. Current and projected number of years of life lost due to prostate cancer: a global study. Prostate. 2022;82(11):1088–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.24360.

Monga U, Kerrigan AJ, Thornby J, Monga TN, Zimmermann KP. Longitudinal study of quality of life in patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(3):391. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2004.06.0071.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21387.

Thong MSY, van Noorden CJF, Steindorf K, Arndt V. Cancer-related fatigue: causes and current treatment options. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2020;21(2):17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-020-0707-5.

Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Mustian K, Okunieff P, Bole CW. Frequency, severity, clinical course, and correlates of fatigue in 372 patients during 5 weeks of radiotherapy for cancer. Cancer. 2005;104(8):1772–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21364.

Stout NL, Baima J, Swisher AK, Winters-Stone KM, Welsh J. A systematic review of exercise systematic reviews in the cancer literature (2005-2017). PM&R. 2017;9:S347–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.07.074.

Wallen MP, Hennessy D, Brown S, et al. High-intensity interval training improves cardiorespiratory fitness in cancer patients and survivors: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(4):e13267. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13267.

Baguley BJ, Adlard K, Jenkins D, Wright ORL, Skinner TL. Mediterranean style dietary pattern with high intensity interval training in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: a pilot randomised control trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095709.

Mugele H, Freitag N, Wilhelmi J, et al. High-intensity interval training in the therapy and aftercare of cancer patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(2):205–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00743-3.

MacInnis MJ, Gibala MJ. Physiological adaptations to interval training and the role of exercise intensity. J Physiol. 2017;595(9):2915–30. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP273196.

Piraux E, Caty G, Renard L, et al. Effects of high-intensity interval training compared with resistance training in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021;24(1):156–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-020-0259-6.

Papadopoulos E, Gillen J, Moore D, et al. High-intensity interval training or resistance training versus usual care in men with prostate cancer on active surveillance: a 3-arm feasibility randomized controlled trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(12):1535–44. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2021-0365.

Djurhuus SS, Simonsen C, Toft BG, et al. Exercise training to increase tumour natural killer-cell infiltration in men with localised prostate cancer: a randomised controlled trial. BJU Int. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15842 Published online July 18.

Kang DW, Fairey AS, Boulé NG, Field CJ, Wharton SA, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness and biochemical progression in men with localized prostate cancer under active surveillance. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):1487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3067.

Kang DW, Fairey AS, Boulé NG, Field CJ, Wharton SA, Courneya KS. A randomized trial of the effects of exercise on anxiety, fear of cancer progression and quality of life in prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2022;207(4):814–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000002334.

Lu Y, Wang W, Ding X, Shi X. Association between the promoter region of serotonin transporter polymorphisms and recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a meta-analysis. Arch Oral Biol. 2020;109:104555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.104555.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Sports Med. 2013;43(10):927–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0066-5.

Lakoski SG, Willis BL, Barlow CE, et al. Midlife cardiorespiratory fitness, incident cancer, and survival after cancer in men. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(2):231. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0226.

Bourke L, Smith D, Steed L, et al. Exercise for men with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016;69(4):693–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.047.

Jensen L, Bangsbo J, Hellsten Y. Effect of high intensity training on capillarization and presence of angiogenic factors in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2004;557(2):571–82. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057711.

de Araujo GG, Papoti M, dos Reis IGM, de Mello MAR, Gobatto CA. Short and long term effects of high-intensity interval training on hormones, metabolites, antioxidant system, glycogen concentration, and aerobic performance adaptations in rats. Front Physiol. 2016;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00505.

Laursen PB. Training for intense exercise performance: high-intensity or high-volume training? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01184.x.

Cunha TS, Tanno AP, Costa Sampaio Moura MJ, Marcondes FK. Influence of high-intensity exercise training and anabolic androgenic steroid treatment on rat tissue glycogen content. Life Sci. 2005;77(9):1030–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.001.

Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):961. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914.

Hojan K, Kwiatkowska-Borowczyk E, Leporowska E, et al. Physical exercise for functional capacity, blood immune function, fatigue, and quality of life in high-risk prostate cancer patients during radiotherapy: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(4):489–501 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26761561.

Monga U, Garber SL, Thornby J, et al. Exercise prevents fatigue and improves quality of life in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1416–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.110.

Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Spry N, et al. Effects of different exercise modalities on fatigue in prostate cancer patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a year-long randomised controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2017;72(2):293–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.019.

Galvão DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Newton RU. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):340–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488.

LaVoy ECP, Fagundes CP, Dantzer R. Exercise, inflammation, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2016;22:82–93 PMC4755327.

Devin JL, Sax AT, Hughes GI, et al. The influence of high-intensity compared with moderate-intensity exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(3):467–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0490-7.

Weston KS, Wisløff U, Coombes JS. High-intensity interval training in patients with lifestyle-induced cardiometabolic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(16):1227–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092576.

Samiea A, Yoon JSJ, Ong CJ, Zoubeidi A, Chamberlain TC, Mui ALF. Interleukin-10 induces expression of neuroendocrine markers and pdl1 in prostate cancer cells. Prostate Cancer. 2020;2020:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5305306.

Ma L, Zhao J, Li T, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-74.

Lilja H, Ulmert D, Björk T, et al. Long-term prediction of prostate cancer up to 25 years before diagnosis of prostate cancer using prostate kallikreins measured at age 44 to 50 years. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(4):431–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9351.

Fang J, Metter EJ, Landis P, Chan DW, Morrell CH, Carter HB. Low levels of prostate-specific antigen predict long-term risk of prostate cancer: results from the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Urology. 2001;58(3):411–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01304-8.

Carter HB, Ferrucci L, Kettermann A, et al. Detection of life-threatening prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen velocity during a window of curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(21):1521–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djj410.

Loeb S, Catalona WJ. Prostate-specific antigen screening: pro. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20(3):185–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283384047.

Lott C, Araujo R, Cassar MR, et al. The European trauma course (ETC) and the team approach: past, present and future. Resuscitation. 2009;80(10):1192–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.023.

Bourke L, Stevenson R, Turner R, et al. Exercise training as a novel primary treatment for localised prostate cancer: a multi-site randomised controlled phase II study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26682-0.

Pedersen L, Idorn M, Olofsson GH, et al. Voluntary running suppresses tumor growth through epinephrine- and IL-6-dependent NK cell mobilization and redistribution. Cell Metab. 2016;23(3):554–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.011.

Hojman P, Gehl J, Christensen JF, Pedersen BK. Molecular mechanisms linking exercise to cancer prevention and treatment. Cell Metab. 2018;27(1):10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.015.

Biro PA, Thomas F, Ujvari B, Beckmann C. Can energetic capacity help explain why physical activity reduces cancer risk? Trends Cancer. 2020;6(10):829–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.06.001.

Idorn M, Hojman P. Exercise-dependent regulation of NK cells in cancer protection. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(7):565–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2016.05.007.

Hvid T, Lindegaard B, Winding K, et al. Effect of a 2-year home-based endurance training intervention on physiological function and PSA doubling time in prostate cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(2):165–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0694-1.

Hayes BD, Brady L, Pollak M, Finn SP. Exercise and prostate cancer: evidence and proposed mechanisms for disease modification. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(9):1281–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0223.

Rundqvist H, Augsten M, Strömberg A, et al. Effect of acute exercise on prostate cancer cell growth. Lobaccaro JMA, ed. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067579.

McCullough DJ, Nguyen LMD, Siemann DW, Behnke BJ. Effects of exercise training on tumor hypoxia and vascular function in the rodent preclinical orthotopic prostate cancer model. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115(12):1846–54. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00949.2013.

Lee K, Zhou J, Norris MK, Chow C, Dieli-Conwright CM. Prehabilitative exercise for the enhancement of physical, psychosocial, and biological outcomes among patients diagnosed with cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(7):71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-020-00932-9.

Neal D, Lilja H. Circulating tumor cell count as an indicator of treatment benefit in advanced prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;70(6):993–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.014.

Taylor RA, Farrelly SG, Clark AK, Watt MJ. Early intervention exercise training does not delay prostate cancer progression in Pten −/− mice. Prostate. 2020;80(11):906–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.24024.

Ussing A, Mikkelsen MLK, Villumsen BR, et al. Supervised exercise therapy compared with no exercise therapy to reverse debilitating effects of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25(3):491–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-021-00450-0.

Nilsen TIL, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ. Recreational physical activity and risk of prostate cancer: a prospective population-based study in Norway (the HUNT study). Int J Cancer. 2006;119(12):2943–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22184.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC and JW conceived the study concept and participated in its design, data extraction, statistical analysis, manuscript drafting, and editing. HH and SX participated in the literature research, manuscript drafting, and editing. MC and JW participated in the design and data extraction. AM participated in the manuscript drafting, editing, and statistical analysis. MC, JW, and AM conceived the study concept and participated in data analysis. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the manuscript and agreed to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, M., Wang, J., Hashim, H.A. et al. Effect of high-intensity interval training on aerobic capacity and fatigue among patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Onc 20, 348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02807-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02807-8