Abstract

Background

Pituicytoma is a rare pituitary non-neuroendocrine tumour. The awareness of pituitary non-neuroendocrine tumours has gradually increased over the past several decades, but the knowledge of some histological variants of the tumours is limited, particularly in clinicopathological significance. Here, we report a rare case of pituicytoma variant.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old man presented with sudden symptoms of stroke including urinary incontinence, weakness in right lower limb, and trouble speaking. Physical examinations showed a right facial paralysis. The radiological examinations eventually found a 1.7 × 1.4 × 1.3 cm sellar occupied lesion. After symptomatic treatment improved the symptoms, the patient underwent transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary mass. Histologically, the tumour contained hypocellular area and hypercellular area. The hypocellular area showed elongated spindle cells arranged in a fascicular pattern around small vessels and scattered Herring bodies; the hypercellular area showed a large number of pseudorosettes. Immunohistochemistrically, the tumour cells were positive for thyroid transcription factor-1, S100, and neuron-specific enolase. Neurofilament only showed a little positive in the hypocellular area, and silver impregnation was only noted in a perivascular distribution. The patient had no recurrence 4 months after the surgery.

Conclusions

The rare variant of pituicytoma has a favourable prognosis. Moreover, it needs to be distinguished pituicytomas with pseudorosettes from ependymomas because of different prognosis. Lastly, Herring bodies may occasionally be seen in the pituicytoma, which could be a potential diagnostic pitfall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The most common pituitary tumour is pituitary adenoma that is a neuroendocrine tumour, whereas pituitary non-neuroendocrine tumours are rare and include pituicytoma, spindle cell oncocytoma (SCO), granular cell tumour (GCT), and gangliocytoma according to the 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system (CNS). The former three tumours have been found to arise from pituicytes and may constitute a spectrum of a single nosological entity because they are positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1), a specific histogenetic marker of pituicytes [1]. The awareness of pituitary non-neuroendocrine tumours has gradually increased over the past several decades, but the knowledge of some histological variants of the tumours is limited, particularly in clinicopathological significance. To improve the awareness of the variants, we report a rare case of a pituicytoma with a biphasic pattern and admixed with scattered Herring bodies.

Case presentation

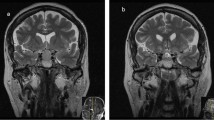

This patient was a 71-year-old man with a history of grade 2 hypertension for 30 years, and he presented with dizziness for a week. As sudden urinary incontinence, weakness in right lower limb, and trouble speaking, he underwent an emergency non-enhanced head computed tomography (CT) examination. The CT examination showed a slightly low-density area in the left frontal lobe and the left temporal lobe, which raised a suspicion for acute infarctions. The following contrast-enhanced head CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations showed no infarction, but a 1.7 × 1.4 × 1.3 cm sellar occupied lesion with heterogeneous enhancement (Fig. 1a, b). The patient had normal levels of pituitary hormones. Physical examinations showed the mouth drawn to the left side, the right nasolabial fold blunting, and the deviation of the protruded tongue toward the right side, which indicated a right facial paralysis. The symptoms were effectively relieved after the patient underwent the drug treatment including aspirin and atorvastatin for secondary prevention of stroke and ginkgo biloba extract for symptomatic treatment. The patient subsequently underwent transsphenoidal resection of pituitary mass on October 22, 2019.

The greyish-white colour resected specimen was about 1.5 cm in diameter. Histologically, this tumour contained hypocellular and hypercellular areas that showed apparent geographical separation (Fig. 2a). The hypocellular area showed elongated spindle cells arranged in a fascicular pattern around small vessels and scattered Herring bodies. The spindle cell had blunted-ended to irregular nuclei with abundant, palely eosinophilic, fibrillary cytoplasm (Fig. 2b). The hypercellular area was characterised by pseudorosettes in which the tumour cells showed crowding, overlapping the nucleus with speckled nuclear chromatin (Fig. 2c). Mitoses were not seen in the tumour. Immunohistochemistrically, the tumour cells showed diffuse nuclear expression of TTF1 (Fig. 2d). S100 (Fig. 3a) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (Fig. 3b) expressed in the tumour cells and Herring bodies. Neurofilament (NF) was completely negative in the hypercellular area but had a little positive in the hypocellular area (Fig. 3c). Silver impregnation was only noted in a perivascular distribution (Fig. 3d). Ki-67 showed extremely low proliferative index in the tumour. The other markers were negative, including glial fibrillary acidic protein, Olig2, SOX10, CD68, adrenocorticotropic hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone, growth hormone, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, SF1, PIT1, TPIT, cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, CD68, and Galectin-3, neither was periodic acid–Schiff. The final diagnosis was pituicytoma with a biphasic pattern and admixed with scattered Herring bodies. The patient made a good postoperative recovery and had no recurrence at 4 months of MRI follow-up.

a The hypocellular area (top) and hypercellular area (bottom) showed apparent geographical separation. b In the hypocellular area, the spindle cells had blunted-ended to irregular nuclei with abundant, palely eosinophilic, fibrillary cytoplasm, and admixed with scattered Herring bodies (arrow). c In the hypercellular zone, a large number of pseudorosettes reminiscent of ependymoma. d Strong and diffuse nuclear staining for TTF1 in the hypocellular and hypercellular areas

Discussion and conclusions

Diligent clinical correlation, together with some appropriate immunohistochemical panel, is generally sufficient to reach the correct diagnosis of a rare tumour with an unusual morphology. Clinically, the symptoms of stroke pushed the radiologist to focus on looking for some suspicious cerebrovascular disease manifestation on the non-enhanced CT scan, resulting in missing the apparent lesion showed on the following contrast-enhanced CT and MRI examination: sellar tumour. Immunohistochemistrically, the tumour cells were positive for TTF1, S100, and NSE. According to the 2016 WHO classification of tumours of CNS, the tumour should fall within pituitary non-neuroendocrine TTF1-expressing tumours. Among the umbrella term encompassing pituicytoma, GCT, and SCO, pituicytoma was eventually picked out to diagnose the sellar tumour based on the following analyses.

GCT and SCO have been referred to constitute pituicytomas that are composed of tumour cells with lysosome-rich and mitochondrion-rich cytoplasm, respectively [1]. The lysosome is identified in practice by CD68 marker that belongs to the lysosome-associated membrane protein family of molecules [2] and consistently expresses in lysosome-rich cells [3,4,5]. Mitochondrion-rich cells usually show apparent eosinophilic cytoplasm, such as Hürthle cell [6], and gastric parietal cells [7]. Moreover, there is evidence that most of SCO are positive for epithelial membrane antigen and Galectin-3 [8]. In this case, the tumour cells are negative for the three markers and lack apparent eosinophilic cytoplasm, so the diagnosis of pituicytoma is appropriate. This pituicytoma presents some unusual morphological features that we will focus on in the following.

This pituicytoma rarely contains two different morphological areas. In the hypercellular area, a large number of pseudorosettes are reminiscent of ependymoma. The pattern presented in sellar tumours has been described in some literature, but the nomenclature is not well established owing to limited understanding of them, with different studies referring to the tumour as “ependymoma” or “pituicytoma with an ependymoma-like component” [9,10,11,12,13]. Compared with the pituicytoma that arose from pituicytes, which are associated with a favourable outcome according to the 2016 WHO classification of tumours of CNS, the ependymoma that arose from ependymal cells are defined as WHO grade II or III malignant tumours that have a variable clinical outcome, ranging from long-term disease-free survival after surgery to local recurrence to metastasis [14, 15]. Considering the different prognosis, ependymoma and pituicytoma should be distinguished. To distinguish the two that have different cells of origin, the best way is to perform a specific histogenetic immune marker of pituicytes: TTF1. As the marker is diffusely expressed in the tumour cells, the diagnosis of pituicytoma with an ependymoma-like component is confirmed in the hypercellular area. The hypocellular area is reminiscent of a normal neurohypophysis. In the neurohypophysis, silver impregnation or NF stain can demonstrate such axonal processes originated from the hypothalamus, traverse the pituitary stalk, to the perivascular zones of the posterior lobe [16]. However, the stains show almost complete loss of the axons in the hypocellular area. Moreover, the area shows that the cells have more abundant cytoplasm with mild nuclear atypia, and has a higher cellular density, than the neurohypophysis. The findings actually reflect the ability of tumour proliferation and invasion in the area, so the hypocellular area should be a part of the pituicytoma. This pituicytoma lacks a histological continuity between the two areas (as shown in Fig. 2a), so we speculate that it is multicentric.

Herring bodies, dilated terminal portions of neurosecretory axons from the hypothalamus and stored antidiuretic hormone and oxytocin, are regarded as a useful diagnostic clue of neurohypophysis according to the 2016 WHO classification. However, Herring bodies have been described in at least four cases of pituicytoma, including ours [12, 17, 18]. In this case, Herring bodies only presented in the hypocellular area. In the area, the tumour ability to destroy the axons is weaker than in the hypercellular area based on observing the NF stain. Therefore, we speculate that Herring bodies can be alive when the tumour invasive ability is rather weak. Moreover, the patient should have presented abnormal levels of antidiuretic hormone or oxytocin, or hormone-related symptom due to the abnormal Herring bodies lacked the connection of axons with the hypothalamus, but either this case or the other three cases have not. The underlying mechanism by which abnormal Herring bodies of pituicytoma never cause hormone imbalances warrants further study.

In conclusion, the rare variant of pituicytoma has a favourable prognosis. Moreover, it is necessary to distinguish the pituicytoma with pseudorosettes from the ependymoma because of different prognosis. Lastly, Herring bodies can occasionally be seen in a pituicytoma, which is a potential diagnostic pitfall.

Availability of data and materials

All the original data supporting our research are described in this article.

Abbreviations

- SCO:

-

Spindle cell oncocytoma

- GCT:

-

Granular cell tumour

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- TTF1:

-

Thyroid transcription factor 1

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSE:

-

Neuron-specific enolase

- NF:

-

Neurofilament

References

Lee EB, Tihan T, Scheithauer BW, Zhang PJ, Gonatas NK. Thyroid transcription factor 1 expression in sellar tumors: a histogenetic marker? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(5):482–8.

Chistiakov DA, Killingsworth MC, Myasoedova VA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. CD68/macrosialin: not just a histochemical marker. Lab Invest. 2017;97(1):4–13.

Yang GZ, Li J. Granular cell tumor of the neurohypophysis with TFE-3 expression: a rare case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25(8):751–4.

Le BH, Boyer PJ, Lewis JE, Kapadia SB. Granular cell tumor: immunohistochemical assessment of inhibin-alpha, protein gene product 9.5, S100 protein, CD68, and Ki-67 proliferative index with clinical correlation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(7):771–5.

Kurtin PJ, Bonin DM. Immunohistochemical demonstration of the lysosome-associated glycoprotein CD68 (KP-1) in granular cell tumors and schwannomas. Hum Pathol. 1994;25(11):1172–8.

Gonzalez-Campora R, Herrero-Zapatero A, Lerma E, Sanchez F, Galera H. Hurthle cell and mitochondrion-rich cell tumors. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1986;57(6):1154–63.

Karam SM, Straiton T, Hassan WM, Leblond CP. Defining epithelial cell progenitors in the human oxyntic mucosa. Stem Cells. 2003;21(3):322–36.

Sali A, Epari S, Tampi C, Goel A. Spindle cell oncocytoma of adenohypophysis: review of literature and report of another recurrent case. Neuropathology. 2017;37(6):535–43.

Scheithauer BW, Swearingen B, Whyte ET, Auluck PK, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO. Ependymoma of the sella turcica: a variant of pituicytoma. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(3):435–40.

Yoshimoto T, Takahashi-Fujigasaki J, Inoshita N, Fukuhara N, Nishioka H, Yamada S. TTF-1-positive oncocytic sellar tumor with follicle formation/ependymal differentiation: non-adenomatous tumor capable of two different interpretations as a pituicytoma or a spindle cell oncocytoma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015;32(3):221–7.

Saeed Kamil Z, Sinson G, Gucer H, Asa SL, Mete O. TTF-1 expressing sellar neoplasm with ependymal rosettes and oncocytic change: mixed ependymal and oncocytic variant pituicytoma. Endocr Pathol. 2014;25(4):436–8.

Kwon MJ, Suh YL. Pituicytoma with unusual histological features. Pathol Int. 2011;61(10):598–602.

Vajtai I, Beck J, Kappeler A, Hewer E. Spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary gland with follicle-like component: organotypic differentiation to support its origin from folliculo-stellate cells. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(2):253–8.

Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sill M, Isserlin R, Benner A, Hielscher T, Milde T, Remke M, et al. Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(2):143–57.

Ross GW, Rubinstein LJ. Lack of histopathological correlation of malignant ependymomas with postoperative survival. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(1):31–6.

Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW, Staugaitis SM, Holtzman RN, Morgello S, Burger PC. Pituicytoma: a distinctive low-grade glioma of the neurohypophysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(3):362–8.

Takei H, Goodman JC, Tanaka S, Bhattacharjee MB, Bahrami A, Powell SZ. Pituicytoma incidentally found at autopsy. Pathol Int. 2005;55(11):745–9.

Ulm AJ, Yachnis AT, Brat DJ, Rhoton AL Jr. Pituicytoma: report of two cases and clues regarding histogenesis. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(3):753–7 discussion 757-758.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was funded by the Key Project of Chongqing Municipal Health Bureau, China (grant no. 2012-1-79). It played key roles in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Cao YD, Zeng Y, Qin X, Tan YW, Zeng M, Wang LJ, Cao XJ, Zou LF, and Wang CL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wang CL, and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Chongqing University. The patient gave consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Y., Zeng, Y., Qin, X. et al. A rare case report of pituicytoma with biphasic pattern and admixed with scattered Herring bodies. World J Surg Onc 18, 108 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01889-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01889-6