Abstract

Background

The giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma is a very rare benign tumor of the prostate gland. It is composed of predominantly cystic enlarged prostatic glands in a fibrous stroma and spreads extensively into the pelvis. Because of the large size at the time of diagnosis, it is not always possible to determine the exact point of origin for these multilocular cystic neoplasms. Thus, diagnosis before histological examination of a surgical specimen is often difficult. Here, we present a case involving one of the largest giant multilocular prostatic cystadenomas reported in the literature and discuss preoperative diagnoses and appropriate surgical approaches for this rare retroperitoneal tumor.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of abdominal distension and lower urinary symptoms. Enhanced CT showed a large retroperitoneal mass with multiple septations in the pelvis and lower abdomen, measuring 30 cm in size, surrounding the rectum and displacing the bladder, prostate, and seminal vesicle to the right anterior side. MRI showed multiple cysts with a simple fluid appearance on T2-weighted images and enhanced solid components on gadolinium-enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted images, suggesting the retroperitoneal mass as leiomyoma with cystic degeneration or perivascular epithelioid cell tumor. Biopsy of the mass showed a spindle cell tumor with focal smooth muscle differentiation. Differential diagnosis comprising leiomyoma, low-grade leiomyosarcoma, and perivascular epithelioid cell tumor was made. Complete resection of the tumor with low anterior resection of the rectum was performed. The tumor was solid with multilocular cavities containing blackish-brown fluid and measured 33 × 23 × 10 cm. Histologically, the tumor was composed of variously sized dilated glandular structures lined by prostatic epithelia surrounded by fibromuscular stroma. The prostatic nature of the lesions was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining of the epithelium for prostate-specific antigen. Thus, pathological diagnosis was a giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma.

Conclusions

We present our experiences with one of the largest giant multilocular prostatic cystadenomas. When a retroperitoneal huge lesion with locular cavities fills the pelvis in a male patient, the possibility of giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma should be considered before planning for retroperitoneal tumor treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Retroperitoneal tumors often present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Although computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for diagnosis and understanding the extent of disease, a definitive diagnosis can be established only by histopathologic analysis after surgery. Knowledge of the tumor characteristics may help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Here, we report a case of a giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma, an extremely rare benign neoplasm that originates in the prostate glands. Fewer than 30 cases have been reported thus far [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Our case was one of the largest reported to date, as it measured 33 cm in length and occupied the whole pelvis up to the level of the navel.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of abdominal distension. He also had lower urinary symptoms such as the sensation of incomplete voiding and increased frequency. He had no symptoms of bowel obstruction. Physical examination revealed a palpable mass occupying the lower abdomen up to the level of the navel, but there was no tenderness. Digital rectal examination revealed an elastic hard mass on the anterior side of the rectum without palpable intraluminal mass. Total colonoscopy showed no masses or stenosis in the rectum. We evaluated the urinary symptoms were due to the compression of the bladder by the tumor.

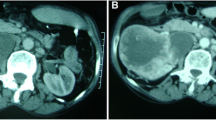

The results of laboratory tests were normal. Serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was not available preoperatively. Urinalysis was normal, with no evidence of hematuria. Enhanced CT showed a large retroperitoneal mass measuring 30 cm in size with multiple septations surrounding the rectum and displacing the bladder, prostate, and seminal vesicle to the right anterior side (Fig. 1). MRI showed a mass composed of cysts of various sizes ranging from smaller than 1 up to 6 cm and solid components. Whereas most cysts had simple fluid appearance (very high intensity on T2-weighted images), some showed the presence of layering which suggests the likelihood of either fat or blood in content (Fig. 2a, b). Several solid components which showed isointensity on T2-weighted images were enhanced on gadolinium-enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted images (Fig. 2c–f). From these radiological findings, preoperative diagnosis was leiomyoma with cystic degeneration or perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (Fig. 2). Biopsy of the mass was performed under CT guidance, and histology showed a spindle cell tumor. Immunohistochemically, preoperative biopsy of the tumor showed positive staining for SMA, desmin, and caldesmon while negative for S-100, HMB-45, and MDM2, indicating smooth muscle differentiation. Differential diagnosis of leiomyoma, low-grade leiomyosarcoma, and perivascular epithelioid cell tumor was made. We suspected the tumor originated from the smooth muscle of the bladder or deep soft tissue in the retroperitoneal space.

a, b T2-weighted MRI. Most cysts showed high intensity suggesting simple fluid, and some showed the presence of layering which suggests the likelihood of either fat or blood in content. The arrowheads show the presence of layering within the cystic areas. c, d Non-enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI and e, f gadolinium-enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI. Several solid components were enhanced

As the biopsy findings did not reveal obvious evidence of malignancy and because the outer wall of the tumor was relatively smooth, we chose to forego total pelvic exenteration and instead attempt complete macroscopic resection of the tumor with minimal combined resection of adjacent organs.

Laparotomy was performed through a midline incision, which revealed a huge mass from the pelvic floor up to the level of the navel (Fig. 3). During exploration, the bilateral ureter was preserved but the vas deferens was resected. Because the plane of the interface between the bladder and tumor was unrecognizable, we injected air into the bladder and identified the border of the mass. We dissected the tumor, preserving the bladder and prostate with partial resection of the prostate. The tumor was not attached to the sacrum or levator ani and was mobilized from the pelvic floor. Because the tumor extended into the left pelvic sidewall and surrounded the rectum, we sacrificed the rectum as well as the left hypogastric nerve and left pelvic plexus. Finally, we performed a complete resection of the tumor with low anterior resection. Intraoperatively, the border between the tumor and normal prostate was not so clear.

The gross pathologic specimen was a 33 × 23 × 10 cm solid mass containing multilocular cavities. Sectioning revealed a multicystic cut surface (Fig. 4), and blackish-brown intratumoral fluid was drained from the tumor. Histologically, the tumor was composed of variously sized dilated glandular structures lined by prostatic epithelia surrounded by fibromuscular stroma (Fig. 5a). Lesions of the well-developed, dilated prostate glands resembling prostatic hyperplasia were also evident (Fig. 5b). The cysts were lined by cuboidal to columnar secretory cells and basally located nuclei (Fig. 5c). Cytologically, we observed no atypical features or mitosis. Epithelial cells of the cysts and stromal glands were positive for PSA on immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 5d). The epithelium cells of the tumor were also positive for AR and NKX3.1 staining, indicating that the tumor originated from the prostate. The spindle cells seen on preoperative biopsy were thought to be stromal components of the tumor.

Pathological examination of the resected specimen. a Low-power magnification of cystadenoma of the prostate with dense fibromuscular stroma (H&E, original magnification × 20). b Cystic dilated glandular structures surrounded by a fibrous stroma resembling prostatic hyperplasia (H&E, original magnification × 20). c Glands and cysts are lined by cuboidal to low columnar epithelial cells with basally located nuclei (H&E, original magnification × 40). d The epithelium of the cysts stained positively with prostate-specific antigen stain (× 20)

Final histology indicated a giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma.

Postoperatively, whereas the patient developed a pelvic abscess due to urine leakage from the prostatic urethra, he recovered conservatively and was discharged on postoperative day 37. Since there is no positive evidence of adjuvant therapy of this prostatic cystadenoma, the patient is now under follow-up by blood tests and CT scan every 3–6 months.

At 2 months after surgery, the patient had a PSA of 0.365 ng/ml, which was within the normal ranges. Since then, we have observed no signs of tumor recurrence. The patient was completely asymptomatic at the 6-month follow-up visit and made a full recovery, with no complaints of any urinary disorders or sexual dysfunction.

Discussion and conclusions

A giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma is an extremely rare benign neoplasm that originates in the prostate glands. In 1991, Maluf et al. became the first to describe and designate this rare entity [2]; since then, fewer than 30 cases have been reported (Table 1) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. This type of tumor is typically located along the midline between the bladder and rectum and identified as a large retroperitoneal mass. A definitive diagnosis before histological examination of a surgical biopsy is very difficult, but preoperative assessment is important for surgical treatment planning. Previous reports of giant multilocular prostatic cystadenomas indicate that surgical treatment varies from tumor debulking to total pelvic exenteration. The decision concerning surgical margin is influenced by whether or not the mass is malignant in nature and whether it has invaded adjacent organs. Information on the origin of the mass is also necessary in order to preserve adjacent organs.

Clinical presentation and radiographic features are helpful for preoperative diagnosis. As shown in Table 1, giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma may occur at any age, with reported patient ages ranging from 23 to 80 years at diagnosis. Presenting symptoms are similar to those of benign prostatic hyperplasia and include incomplete voiding and urinary retention. Almost all cases in the literature noted lower urinary symptoms. Enlargement of the mass also causes abdominal distension and gastrointestinal symptoms. Our case initially presented with complaints of abdominal distension, but a detailed interview revealed these to be lower urinary symptoms. Urinalysis often reveals hematuria and elevated serum PSA levels.

Imaging findings of retroperitoneal tumors are often overlapping, and the first step to understanding the tumors is to divide them into solid or cystic tumors. In addition, their content, precise localization, extent of local invasion, and vascularity may help to define a specific differential diagnosis [22]. CT and MRI scans of the present giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma revealed a large retroperitoneal solid mass with multilocular cavities that were compressing adjacent organs, especially the bladder and rectum. As it was located between the bladder and rectum, it was presumed to have arisen from the prostate gland. The mass comprised cysts of various sizes and soft tissue components. MRI may provide additional information, and T2-weighted imaging of the cysts can be suggestive of either fat or blood in the content. MRI may also show attachment to the prostate.

Differential diagnoses of a multicystic retroperitoneal tumor can include liposarcoma, leiomyoma with cystic degeneration, lymphangioma, multilocular peritoneal inclusion cyst, phyllodes variant of atypical prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic abscess, and teratoma. Cysts of the lower male genitourinary tract are uncommon. There are also differential diagnoses for cystic lesions in the pelvis, including Müllerian cysts, utricle cysts, and seminal vesicle cysts. However, these are typically smaller than the giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma and not “multilocular” [23].

Although imaging studies may provide useful information about the extent of the lesion and invasion to adjacent organs, a clear and definitive diagnosis is possible only through histological means. Histologically, a giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma is composed of multiple cysts in hypocellular fibrous stromal tissue and dense fibrous stroma that corresponds to a focal solid area. It is characterized by cuboidal cells lining the prostate glands and cyst, with positive immunohistochemical staining for PSA in epithelial cells [2]. No previous studies have reported a diagnosis of giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma preoperatively by biopsy, and biopsy showed benign prostatic glands and stroma in some reports. The biopsy sample of the tumor in our case showed a spindle cell tumor with focal smooth muscle differentiation [2, 24]. If we could diagnose multilocular prostatic cystadenoma before surgery, that is, if we could suspect that the tumor originated from prostate, we might be able to preserve a normal prostate without prostatic urethra injury.

Treatment for giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma is complete surgical excision. However, adherence to surrounding structures often makes complete resection difficult, and clinical suspicion of malignancy may lead to unnecessarily aggressive surgery and no preservation of urogenital or digestive organs. Despite its benign nature, incomplete resection can result in recurrence [2, 12]. To achieve complete resection, we sacrificed the rectum as well as the left hypogastric nerve and left pelvic plexus, but were able to preserve adjacent organs including the prostate, which resulted in no urinary disorders or sexual dysfunction. Complete resection of giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma should be considered in light of the surgical trauma involved.

One recent report found that a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist is effective for recurrent giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma [12], and this may represent a new treatment option for patients with more aggressive or recurrent giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma.

In conclusion, when a retroperitoneal huge lesion with locular cavities fills the pelvis in men, giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

References

Watanabe J, Konishi T, Takeuchi H, Tomoyoshi T. A case of giant prostatic cystadenoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1990;36:1077–9.

Maluf HM, King ME, DeLuca FR, Navarro J, Talerman A, Young RH. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma: a distinctive lesion of the retroperitoneum in men. A report of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:131–5.

Levy DA, Gogate PA, Hampel N. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma: a rare clinical entity and review of the literature. J Urol. 1993;150:1920–2.

Lim DJ, Hayden RT, Murad T, Nemcek AA Jr, Dalton DP. Multilocular prostatic cystadenoma presenting as a large complex pelvic cystic mass. J Urol. 1993;149:856–9.

Morimoto S, Okuno T, Masuda H, Kasamatsu T, Suzuki S. A case of prostatic cystadenoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1994;40:629–31.

Kirsch AJ, Newhouse J, Hibshoosh H, O’Toole K, Ritter J, Benson MC. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate. Urology. 1996;48:303–5.

Seong BM, Cheon J, Lee JG, Kim JJ, Chae YS. A case of multilocular prostatic cystadenoma. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13:554–8.

Choi YH, Namkung S, Ryu BY, Choi KC, Park YE. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma. J Urol. 2000;163:246–7.

Matsumoto K, Egawa S, Iwabuchi K, Baba S. Prostatic cystadenoma presenting as a large multilocular mass. Int J Urol. 2002;9:410–2.

Rusch D, Moinzadeh A, Hamawy K, Larsen C. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1477–9.

Allen EA, Brinker DA, Coppola D, Diaz JI, Epstein JI. Multilocular prostatic cystadenoma with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Urology. 2003;61:644.

Datta MW, Hosenpud J, Osipov V, Young RH. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate responsive to GnRH antagonists. Urology. 2003;61:225.

Hauck EW, Battmann A, Schmelz HU, Diemer T, Miller J, Weidner W, Knoblauch B. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate: a rare differential diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Int. 2004;73:365–9.

Ganesan S, Ganesan K, Joshi M. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:795–8.

Park JP, Cho NH, Oh YT, Choi YD. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma presenting with obstructive aspermia. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:554–6.

Tuziak T, Spiess PE, Abrahams NA, Wrona A, Tu SM, Czerniak B. Multilocular cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:19–25.

Chowdhury MM, Abdulkarim JA. Case report. Multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate presenting as a giant pelvic mass. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:e200–1.

Lee TK, Chuang ST, Netto GJ. Conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma arising in a multilocular prostatic cystadenoma. Pathol Int. 2010;60:413–6.

Olgun DC, Onal B, Mihmanli I, Kantarci F, Durak H, Demir H, Cetinel B. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate: a rare cause of huge cystic pelvic mass. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:209–13.

Baad M, Ericson K, Yassan L, Oto A, Eggener S, Nottingham CU, Richards KA, Thomas S. Giant multilocular cystadenoma of the prostate. Radiographics. 2015;35:1051–5.

Abed El Rahman D, Zago T, Verduci G, Baroni G, Berardinelli ML, Pea U, Morandi E, Castoldi M. Transperitoneal laparoscopic treatment for recurrence of a giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;88:66–7.

Osman S, Lehnert BE, Elojeimy S, Cruite I, Mannelli L, Bhargava P, Moshiri M. A comprehensive review of the retroperitoneal anatomy, neoplasms, and pattern of disease spread. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013;42:191–208.

Shebel HM, Farg HM, Kolokythas O, El-Diasty T. Cysts of the lower male genitourinary tract: embryologic and anatomic considerations and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2013;33:1125–43.

Paner GP, Lopez-Beltran A, So JS, Antic T, Tsuzuki T, McKenney JK. Spectrum of cystic epithelial tumors of the prostate: most cystadenocarcinomas are ductal type with intracystic papillary pattern. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:886–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tanabe T, Sakamoto R, Moritani K, and Tsukamoto S, all of whom served as staff members at the National Cancer Center Hospital.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YN and DS designed the report, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. YM, YS, SI, and YK collected the patient’s clinical data and coordinated and drafted the manuscript. TS and AY performed the pathological diagnosis and wrote part of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from our hospital’s review board (NCC2017-437).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, Y., Shida, D., Shibayama, T. et al. Giant multilocular prostatic cystadenoma. World J Surg Onc 17, 42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1579-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1579-7