Abstract

Background

The anti-cancer role of metformin has been reported in many different kinds of solid tumors, but how it affects non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is currently elusive. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of metformin treatment on diabetic NSCLC.

Methods

Two hundred fifty-five patients of diabetic NSCLC receiving therapy in our hospital from 2014 to 2016 were enrolled in our study. The information on clinical diagnosis, pathology, and prognosis as well as the influence of metformin in diabetic NSCLC were collected and assessed. Univariate and multivariate analytical techniques were applied to explore how metformin affect the survival of NSCLC.

Results

One hundred fifty of the 255 diabetic NSCLC patients took metformin. The median overall survival time (OST) and disease-free survival time (DFST) were significantly prolonged with metformin treatment compared to without metformin treatment (OST 25.0 vs 11.5 months, p = 0.005; DFST 15.6 vs 8.5 months, p = 0.010). Multivariate analysis indicated that metformin treatment could be used to predict the long-term outcome of diabetic NSCLC independently (HR = 0.588, 95% CI 0.466–0.895, p = 0.035).

Conclusion

Our study revealed that the metformin could help in improving the final outcome of NSCLC patients with diabetes in the long term and thus could be applied to treat NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prognosis of NSCLC remains poor due to diagnosis at advanced stage and the aggressive aspect of NSCLC [1]. Although the diagnosis and therapy had been greatly improved in recent decades, the optimal prognostic factors and treatment for prolonging the survival time of NSCLC still remain to be explored, due to the complexity and heterogeneity of each NSCLC patient [2].

There were about 15–20% of all cancer patients who have diabetes mellitus at the same time [3]. Several studies demonstrated that the type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) could be used independently to predict the outcome of breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and gastric cancer [4,5,6,7,8]. The metformin, an oral hypoglycemic drug for T2DM, was reported to reduce the risk of cancer and cancer-related mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus [9, 10]. Recently, we explored how metformin influenced clinic pathological progress and prognosis of small cell lung cancer (SCLC), found that metformin significantly reduced the recurrence rate of SCLC (p = 0.001), and also demonstrated that metformin could improve the prognosis of SCLC independently [11]. Moreover, some clinical and experimental studies confirmed that metformin had the anti-tumor effect and could prolong the survival time of patients who had been diagnosed of diabetes mellitus accompanied by hepatocellular carcinoma or prostate cancer in a long term [10, 12, 13].

To date, there was few clinical trial or clinical data about the influence of metformin on the outcome of diabetic NSCLC. Thus, our study aimed at exploring how metformin affect clinical properties of a large amount of NSCLC patients, as well as the role of metformin in prognosis of diabetic NSCLC.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the hospital of Nankai, Tianjin, from February 2010 to November 2016. Two hundred fifty-five patients diagnosed with NSCLC and pre-existing T2DM were enrolled in the study, and the diagnosis of NSCLC was based on the histological examination. The study was approved by the ethnic committee of Nankai Hospital, Tianjin. Informed agreement was signed by all the enrolled patients or their relatives. Patients were excluded if (1) the information of clinical therapy or the follow-up was not complete, (2) the metastasis was found in distance or on peritoneum during the surgery, (3) they had type 1 diabetes mellitus, and (4) they received both metformin and insulin treatment.

The clinical information, pathological variables, and therapeutic strategies were all collected and assessed. According to the guideline of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, the response evaluation was performed every two cycles. The follow-up result was obtained by clinical visit or family contact. The OST was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to that of death or the last follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 19.0 was used to perform the statistical analyses. The χ2 test was applied to assess the relationship between metformin treatment and clinical properties. The Kaplan–Meier curves and multivariate analyses were conducted to analyze the outcome and to identify the independent prognostic factors. G Power software [14] was used to perform power analysis for sample size, making sure that enough samples were enrolled in the current study. p values (two sides) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinic pathological features

These patients (Table 1) were divided into two groups, group A: metformin treatment and group B: non-metformin treatment. One hundred fifty (58.8%) patients were included in group A. The metformin dosage changes from 500 mg two times daily (bid) to 1000 mg two times daily for optimal effects. Power analysis using G Power software demonstrated that patient number in current study had adequate power to detect statistical significance (power = 96.6%, type I/II error rate α was 0.05). The main histology (n = 204; 80.0%) of lesion in included patients was non-squamous. Thirty (35.3%) patients experienced a recurrence. There was no significant difference in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) between these two groups (Table 1). Among all the patients, a total of 183 (72.8%) patients received chemotherapy: 105 (70.0%) in group A and 78 (75.3%) in group B. The chemotherapy plan contains carboplatin (Paraplatin) or cisplatin (Platinol) accompanied with docetaxel (Taxotere) and gemcitabine (Gemzar). All the patients also kept taking metformin during the chemotherapy. The median time of following up these patients was 67.0 months.

Correlation between metformin treatment and clinic pathological features

Table 2 indicated the association between the metformin treatment and clinic characteristics in diabetic NSCLC. Our study revealed that the metformin treatment significantly inhibit the tumor recurrence (p = 0.015) of these NSCLC patients. However, the effect of metformin treatment was not associated with patients’ gender, age, location of primary tumor, and the histology (p > 0.05).

Survival analysis for diabetic NSCLC patients

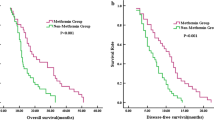

As Fig. 1 indicated, the overall survival time (OST) of the diabetic NSCLC patients in group A was longer than that in group B (OST 25.0 and 11.5 months relatively, p = 0.005). In addition, disease-free survival time (DFST) of the diabetic NSCLC patients in group A is longer than that in group B (p = 0.010; Fig. 2). Therefore, metformin treatment can improve the prognosis of diabetic NSCLC.

Univariate analysis showed that the stage of tumor (p = 0.037), tumor recurrence (p = 0.010), and metformin treatment (p = 0.005) could significantly affect OST. Moreover, the tumor stage (p = 0.001) and metformin treatment (p = 0.010) could be used as the prognosis indicator of DFS (Table 2). The further multivariate analysis indicated that the tumor stage (HR = 1.758, p = 0.022) and metformin treatment (HR = 0.687, p = 0.011) could be used as independent factors for DFS (Table 3). The tumor stage (HR = 1.510, p = 0.008), tumor recurrence (HR = 1.700, p = 0.017), and metformin treatment (HR = 0.588, p = 0.035) were confirmed to predict the prognosis of OS independently (Table 3).

Discussion

Lung cancer is the most common causes of cancer death worldwide [15]. As one subgroup of lung cancers, NSCLC represents about 80% of all lung cancers diagnosed [1]. Most NSCLC patients already present with advanced stages at initial diagnosis, metastasis, and early relapse. Moreover, the prognosis of NSCLC remains unsatisfactory [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to find more sensitive NSCLC biomarkers and effective novel drugs to prolong the OST of NSCLC. In our study, metformin treatment were found to inhibit the tumor recurrence (p = 0.001) and present a beneficial prognosis of diabetic NSCLC.

Several studies have reported that metformin was beneficial for the prognosis of several solid tumors [9,10,11,12, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. However, there were few reports about the role of metformin in diabetic NSCLC, which encouraged our study on the role of metformin in diabetic NSCLC.

From the current study, the most important finding was that the patients in group A as compared with group B were less likely to have a tumor relapse (Table 1). However, the effect of metformin treatment on diabetic NSCLC was not associated with age, gender, stage, and pathological type. These results were consistent with our previous study and other researches [22,23,24]. Recently, several researches reported that T2DM was more likely to induce poorer prognosis [25, 26]. Moreover, metformin improved survival benefit in NSCLC compared with other treatment agents for diabetes. Metformin treatment survival time in diabetic NSCLC patients was almost the same as that of nondiabetic people [27]. We, also found that the long-term outcome was significantly improved in group A compared to group B (OST 25.0 vs 11.5 months, p = 0.005; DFS 12.0 vs 6.5 months, p = 0.010) (Figs. 1 and 2). Multivariate Cox analysis indicated that the metformin treatment (p = 0.035) could be used to predict the long-term prognosis of diabetic NSCLC independently in addition to the stage (p = 0.008) and tumor recurrence (p = 0.017) (Table 3). OST was confirmed to be negatively affected by the tumor recurrence and tumor stage, but positively influenced by metformin administration. These data indicated that metformin delayed tumor progression and prolonged the survival time, thus might be a potential therapeutic candidate for diabetic NSCLC patients. These clinical data also further demonstrated that metformin might have anti-cancer properties, which were consistent with late studies. By targeting at multiple pathways or events, such as mammalian target of rapamycin, cell cycle, inflammation, glucose metabolism, angiogenesis, and cancer stem cells, metformin plays its possible anti-cancer role; among them, the AMPK activation is believed to mediate the most effects of metformin [28, 29].

This study has some limitations, which have to be presented. Firstly, some diabetes mellitus-related factors were not collected completely in this retrospective study. Secondly, the patient size in our study was relatively small, and results were needed to be further confirmed. Lastly, the molecular mechanisms of metformin’s beneficial effect on NSCLC prognosis were not clarified. In conclusion, further studies with more enrolled patients, designed with randomized clinical trials, and including molecular mechanism studies are needed in the future.

Conclusion

Our data indicated that metformin treatment could improve the outcome of diabetic NSCLC. Thus, it might be considered as a potentially useful prognostic indicator and anti-cancer drug of diabetic NSCLC.

References

Dietel M, Bubendorf L, Dingemans AM, Dooms C, Elmberger G, Garcia RC, Kerr KM, Lim E, Lopez-Rios F, Thunnissen E, et al. Diagnostic procedures for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): recommendations of the European Expert Group. Thorax. 2016;71:177–84.

Fisher R, Pusztai L, Swanton C. Cancer heterogeneity: implications for targeted therapeutics. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:479–85.

Lee W, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK. Comparative study of diabetes mellitus resolution according to reconstruction type after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with diabetes mellitus. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1238–43.

Yuan C, Rubinson DA, Qian ZR, Wu C, Kraft P, Bao Y, Ogino S, Ng K, Clancy TE, Swanson RS, et al. Survival among patients with pancreatic cancer and long-standing or recent-onset diabetes mellitus. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:29–35.

Salvatore T, Marfella R, Rizzo MR, Sasso FC. Pancreatic cancer and diabetes: a two-way relationship in the perspective of diabetologist. Int J Surg. 2015;21(Suppl 1):S72–7.

Gong Y, Wei B, Yu L, Pan W. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of oral cancer and precancerous lesions: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:332–40.

Xu HL, Tan YT, Epplein M, Li HL, Gao J, Gao YT, Zheng W, Shu XO, Xiang YB. Population-based cohort studies of type 2 diabetes and stomach cancer risk in Chinese men and women. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:294–8.

Yeo Y, Ma SH, Hwang Y, Horn-Ross PL, Hsing A, Lee KE, Park YJ, Park DJ, Yoo KY, Park SK. Diabetes mellitus and risk of thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98135.

Zheng L, Yang W, Wu F, Wang C, Yu L, Tang L, Qiu B, Li Y, Guo L, Wu M, et al. Prognostic significance of AMPK activation and therapeutic effects of metformin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5372–80.

Bayraktar S, Hernadez-Aya LF, Lei X, Meric-Bernstam F, Litton JK, Hsu L, Hortobagyi GN, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Effect of metformin on survival outcomes in diabetic patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1202–11.

Xu T, Liang G, Yang L, Zhang F. Prognosis of small cell lung cancer patients with diabetes treated with metformin. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:819–24.

He XX, Tu SM, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Thiazolidinediones and metformin associated with improved survival of diabetic prostate cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2640–5.

He X, Esteva FJ, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Metformin and thiazolidinediones are associated with improved breast cancer-specific survival of diabetic women with HER2+ breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1771–80.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, & Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

Kato K, Iwama H, Yamashita T, Kobayashi K, Fujihara S, Fujimori T, Kamada H, Kobara H, Masaki T. The anti-diabetic drug metformin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo: study of the microRNAs associated with the antitumor effect of metformin. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:1582–92.

Wang J, Gao Q, Wang D, Wang Z, Hu C. Metformin inhibits growth of lung adenocarcinoma cells by inducing apoptosis via the mitochondria-mediated pathway. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:1343–9.

Xu H, Chen K, Jia X, Tian Y, Dai Y, Li D, Xie J, Tao M, Mao Y. Metformin use is associated with better survival of breast cancer patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2015;20:1236–44.

Van De Voorde L, Janssen L, Larue R, Houben R, Buijsen J, Sosef M, Vanneste B, Schraepen MC, Berbee M, Lambin P. Can metformin improve ‘the tomorrow’ of patients treated for oesophageal cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1333–9.

Hwang IC, Park SM, Shin D, Ahn HY, Rieken M, Shariat SF. Metformin association with lower prostate cancer recurrence in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:595–600.

Zhang T, Guo P, Zhang Y, Xiong H, Yu X, Xu S, Wang X, He D, Jin X. The antidiabetic drug metformin inhibits the proliferation of bladder cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:24603–18.

Tan BX, Yao WX, Ge J, Peng XC, Du XB ZR, Yao B, Xie K, Li LH, Dong H, et al. Prognostic influence of metformin as first-line chemotherapy for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cancer. 2011;117:5103–11.

Lin JJ, Gallagher EJ, Sigel K, Mhango G, Galsky MD, Smith CB, LeRoith D, Wisnivesky JP. Survival of patients with stage IV lung cancer with diabetes treated with metformin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:448–54.

Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL. Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:299–304.

Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, Pollak M, Regensteiner JG, Yee D. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–85.

Habib SL, Rojna M. Diabetes and risk of cancer. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:583786.

Mazzone PJ, Rai H, Beukemann M, Xu M, Jain A, Sasidhar M. The effect of metformin and thiazolidinedione use on lung cancer in diabetics. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:410.

Mohammed A, Janakiram NB, Brewer M, Ritchie RL, Marya A, Lightfoot S, Steele VE, Rao CV. Antidiabetic drug metformin prevents progression of pancreatic cancer by targeting in part cancer stem cells and mTOR signaling. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:649–59.

Daugan M, Dufaÿ Wojcicki A, d’Hayer B, Boudy V. Metformin: an anti-diabetic drug to fight cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:675–85.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Dean’s Fund of Tianjin Nankai Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL and YH collected the clinical data by retrieving patients’ documents. FZ and MQ conducted the statistical analysis. YC drafted the manuscript. TX conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tianjin Nankai Hospital, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients participated in this study

Competing interests

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, T., Li, D., He, Y. et al. Prognostic value of metformin for non-small cell lung cancer patients with diabetes. World J Surg Onc 16, 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1362-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1362-1