Abstract

Background

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) has now become a gold standard approach in radical prostatectomy. The aim of this study was to investigate incidence and risk factors of inguinal hernia (IH) after RARP.

Methods

This study included 307 consecutive men who underwent RARP for the treatment of prostate cancer from January 2011 to August 2015. The incidence of IH after RARP was investigated. Clinical and pathological factors were also investigated to assess relationship with development of postoperative IH.

Results

Median follow-ups were 380 days, and median age of patients was 67 years. Incidence of IH was 11.3, 14.0, and 15.4% at 1, 2, and 3 years after RARP, respectively. Postoperative IH occurrence was significantly associated with low surgeon experience and postoperative incontinence at 3 or 6 months after surgery (P = 0.019, P = 0.002, and P = 0.016, respectively).

Conclusions

Most of the IH occurred within the first 2 years with a rate of 14%. Incidence of IH after RARP was significantly associated with surgical experience and incontinence outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inguinal hernia (IH) is recognized as one of the complications of conventional open retropubic radical prostatectomy (ORRP). Regan et al. first reported IH as a complication of ORRP with an incidence of 12% at 6 months after surgery [1]. Since then, a number of studies indicated high incidence of IH after ORRP [2–8]. In addition, various risk factors are suggested to be associated with IH after ORRP. These factors include lower body mass index (BMI), old age, and history of IH [3, 5, 9]. However, there are few studies reporting the incidence of postoperative IH after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) [2, 10].

Our objective was to assess the incidence of postoperative IH in patients undergoing RARP and investigate relationships between clinico-pathological parameters and incidence of IH after RARP.

Methods

Patient characteristics

This study included 307 consecutive patients who underwent RARP for prostate cancer at The University of Tokyo Hospital between January 2011 and August 2015. Surgeries were carried out by multiple surgeons using the da Vinci-S® (Intuitive Surgical Incorporation, Sunnyvale, CA) with a transperitoneal, six-port technique which was described by Menon et al. [11]. Pneumoperitoneal pressure was maintained at 10 mmHg in standard procedure, while the pressure was elevated to 15 mmHg in procedures such as resection of the dorsal vein complex and nerve preservation. The clinico-pathological demographics of patients of the present study (RARP) were collected and were analyzed in relation to postsurgical IH.

Staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system [12]. Continence was defined as pad-free or 0 g of urinary leakage. “Low surgeon experience” was defined as surgeon experiencing less than 40 cases of RARP surgeries. Standard protocol of follow-ups after discharge was visits at 2 weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12, and every 6 months thereafter. Patients were diagnosed with IH by computed tomography for definite diagnosis.

All the patients provided a written informed consent. This study was approved by the “Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital” (#2283) and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Statistical analyses

Statistical software JMP® Pro version 12 (©2015 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Pearson’s chi-square tests were used for evaluating association between categorical values and incidence of IH, except for values that showed frequency under 5 in which Fisher’s test were used. Significant factors in the univariate analysis and previously reported factors such as age, BMI, history of smoking, and history of IH repair were then evaluated for multivariate analysis using multiple logistic regression models. Kaplan-Meier curve showed the proportion of IH occurrence after RARP in the total population of this study. The date of surgery was defined as time zero, and the date that IH occurred was set as first endpoint. P value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant in any statistical analysis performed in this study.

Results

Clinical characteristics of 307 patients who underwent RARP at our hospital are presented in Table 1. Median age, preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, resected prostate weight, and body mass index were 67 years (interquartile range (IQR); 63–71), 7.7 ng/ml (IQR; 5.6–11.2), 40 grams (IQR; 30–50), and 24 kg/m2 (IQR; 22–25), respectively. Median estimated blood loss, operative, and console time were 300 ml (IQR; 150–600), 237 min (IQR; 200–274), and 183 min (IQR; 152–216), respectively.

A total of 30 men developed IH after RARP (Table 2). There were no significant differences in laterality. Direct hernia was observed in only one patient, and bilateral inguinal hernias were seen in 5 patients.

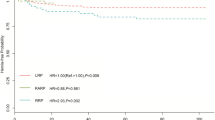

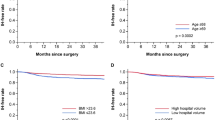

Kaplan-Meier curves showed proportion of IH-free rates in patients who underwent RARP (Fig. 1). Accumulative incidence of IH in patients with RARP was 11.3, 14.0, and 15.4% at 1, 2, and 3 years after surgery, respectively (Fig. 1).

In the univariate analysis regarding preoperative factors, age, BMI, history of smoking, and history of IH repair were not statistically significant factors associated with incidence of IH (Table 3). In addition, preoperative comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus were also investigated but were not significant factors (Table 3). We then investigated postoperative factors and found that low surgeon experience and incontinence at 3 or 6 months were statistically significantly associated with the incidence of IH after RARP (P = 0.019, P = 0.002, and P = 0.016, respectively (Table 4)).

Multivariate analysis showed that low surgical experience (<40 cases) and patients who were incontinent at 3 month were significant factors associated with the occurrence of IH (P = 0.004 and P < 0.001, Table 5).

Discussion

IH is regarded as one of the complications of ORRP. Incidence of IH after ORRP ranges from 12.2 to 23.9% during the first few years [2–8]. However, incidence of IH after RARP is not well known. To our knowledge, there are only two studies regarding incidence of IH after RARP [2, 10]. A European study revealed lower incidence of IH after RARP than after ORRP (12.2 vs. 5.8% at 48 months, respectively) [2]. A study by Lee et al. reported association between the presence of patent processus vaginalis (PPV) and development of IH in patients undergoing RARP [9]. The present study shows new findings that low surgeon experience, and continence outcomes are associated with the incidence of IH after RARP.

In general, IH occurs more frequently among men with low body mass index (BMI), old age, and history of smoking [13, 14]. Anatomically, the internal orifice is penetrated by the spermatic cord and is covered by the transversalis fascia, which act as a supportive structure in preventing development of IH. Patients with overweight have excessive fat and thickness of the abdominal wall that support the preventive effect against hernia formation. Aging may abate tension of the supporting connective tissue surrounding the internal inguinal ring [15]. It may also accelerate deterioration of muscular power of the abdominal muscles [13, 16]. Smoking is a known factor that is related to an increased risk of IH recurrence, since it causes change in the collagen composition by generating tissue hypoxia [14]. However, in the present study, low BMI, aging, and smoking were not significant factors related to the incidence of IH.

Previous reports have explored to identify other factors contributing to IH after radical prostatectomy (RP), whether the surgical types to be open surgery or not. Meta-analysis showed that increasing age, low BMI, previous inguinal hernia repair, presence of postoperative anastomotic stricture, and surgical types other than laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) or radical perineal prostatectomy were the significant factors predicting occurrence of IH [17]. In the present study, none of these factors were significantly associated with incidence of IH. However, one of the novel findings of our study was that development of IH was associated with persistent incontinence at 3 or 6 months after RARP. Factors attributing to IH and failure of gaining continence may be explained from the damage to the seamless pelvic structure including the transversalis fascia and pelvic floor muscles. Excessive damage to the pelvic floor may directly influence the condition of incontinence and, at the same time, weaken tension of the transversalis fascia leading to an increased risk of postoperative IH. In addition, not well-experienced surgeon may excessively spread the working space near the internal orifice when exposing the Retzius space, which may damage the transversalis fascia. This may be the reason to why low surgeon experience was significantly associated with the incidence of IH.

We have previously reported the incidence of IH in patients undergoing minimum incision endoscopic retropubic radical prostatectomy (MIES-RRP) and ORRP [18]. The incidence of IH after radical prostatectomy may be comparable between RARP and ORRP, since accumulative incidence of IH in patients with ORRP were 9.3% at 1 year and 13.1% at 2 years. However, it may be possible that IH may occur more frequently in patients with RARP than those with MIES-RRP, considering the fact that the accumulative incidence of IH in patients with MIES-RRP was 5.9% at 1 year and the same rate at 2 years. This is interesting since the procedures of MIES-RRP and RARP share commonality with the size of skin incision, and yet the incidence of IH seemed to be different. In MIES-RRP, surgeons have smaller limited working area due to the smaller skin incision. Whereas in RARP procedure, with its magnified vision and extended mobility, surgeons can easily achieve exposure with a wider operational area. Therefore, a smaller skin incision in MIES-RRP involves a limited exposed area attenuating the damage that may increase the risk for the development of IH. However, in RARP patients, small skin incision that is made for retrieving the prostate specimen does not affect the range and degree of exposure inside the abdomen, since this incision is made after prostatectomy. Unfortunately, a wider range of good exposure is potentially available in RARP procedure that may lead to an increased risk of developing postoperative IH. Further, based on this idea, it would be easy to understand the low incidence of IH development in patients who undergo laparoscopic radical prostatectomy [19, 20]. The limited mobility of laparoscopic instruments results in a relatively less dissection and damage to the transversalis fascia. To note, incidence of IH is surprisingly low with a range of 0–1.8% after radical perineal prostatectomy, in which the transversalis fascia is intact [21, 22].

In the future, studies demonstrating prophylactic methods may be required, since high incidence of IH is observed in RARP.

Conclusions

The present study shows that the incidence of IH in RARP patients was similar with the previous reports. Interestingly, incidence of IH after RARP was significantly associated with incontinence outcomes.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- IH:

-

Inguinal hernia

- MIES-RRP:

-

Minimum incision endoscopic retropubic radical prostatectomy

- ORRP:

-

Conventional open retropubic radical prostatectomy

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- PW:

-

Prostate weight

- RARP:

-

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy

- RP:

-

Radical prostatectomy

- RRP:

-

Retropubic radical prostatectomy

References

Regan TC, Mordkin RM, Constantinople NL, Spence IJ, Dejter Jr SW. Incidence of inguinal hernias following radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 1996;47(4):536–7.

Stranne J, Johansson E, Nilsson A, et al. Inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: results from a randomized setting and a nonrandomized setting. J Urol. 2010;58:719–26.

Lepor H, Robbins D. Inguinal hernias in men undergoing open radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2007;70(5):961–4.

Abe T, Shinohara N, Harabayashi T. Postoperative inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:326–9.

Sekita N, Suzuki H, Kamijima S. Incidence of inguinal hernia after prostate surgery: open radical retropubic prostatectomy versus open simple prostatectomy versus transurethral resection of the prostate. Int J Urol. 2009;16:110–3.

Ichioka K, Yoshimura K, Utsunomiya N. High incidence of inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2004;63:278–81.

Twu CM, Ou YC, Yang CR, Cheng CL, Ho HC. Predicting risk factors for inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;66:814–8.

Lodding P, Bergdahl C, Nyberg M, Pileblad E, Stranne J, Hugosson J. Inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a study of incidence and risk factors in comparison to no operation and lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:964–7.

Stranne J, Hugosson J, Lodding P. Post-radical retropubic prostatectomy inguinal hernia: an analysis of risk factors with special reference to preoperative inguinal hernia morbidity and pelvic lymph node dissection. J Urol. 2006;176:2072–6.

Lee DH, Jung HB, Chung MS, Lee SH, Chung BH. Patent processus vaginalis in adults who underwent robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: predictive signs of postoperative inguinal hernia in the internal inguinal floor. Int J Urol. 2013;20:177–82.

Menon M, Shrivastava A, Bhandari M, Satyanarayana R, Siva S, Agarwal PK. Vattikuti institute prostatectomy: technical modifications in 2009. Eur Urol. 2009;56:89–96.

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Prostate. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edn. New York: Springer; 2010. p. 457–68.

Rosemar A, Angerås U, Rosengren A. Body mass index and groin hernia. A 34-year follow-up study in Swedish men. Ann Surg. 2008;247(6):1064–8.

Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Bisgaard T, Rosenberg J. Patient-related risk factors for recurrence after inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Surg Innov. 2015;22(3):303–17.

Pans A, Albert A, Lapire CM, et al. Biochemical study of collagen in adult groin hernias. J Surg Res. 2001;95(2):107–13.

Wagh PV, Read RC. Defective collagen synthesis in inguinal herniation. Am J Surg. 1972;124(6):819–22.

Zhu S, Zhang H, Xie L, et al. Risk factors and prevention of inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2013;189:884–90.

Fukuhara H, Nishimatsu H, Suzuki M, et al. Lower incidence of inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy using open gasless endoscopic single-site surgery. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:162–5.

Fujimura T, Menon M, Fukuhara H, et al. Validation of an educational program balancing surgeon training and surgical quality control during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Int J Urol. 2016;23(2):160–6.

Lin BM, Hyndman ME, Steele KE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for inguinal and incisional hernia after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2011;77:957–62.

Hicks J, Douglas J, Eden CG. Incidence of inguinal hernia after radical retropubic, perineal and laparoscopic prostatectomy. Int J Urol. 2009;16:588 [letter].

Matsubara A, Yoneda T, Nakamoto T, et al. Inguinal hernia after radical perineal prostatectomy: comparison with the retropubic approach. Urology. 2007;70:1152–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank K Kawabe (former professor of Department of Urology, The University of Tokyo), T Kitamura (honorary professor of Department of Urology, The University of Tokyo), and Dr. Ishii (Ishii Clinic) for referring many patients that were included in the study.

Funding

There were no funding to support this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting this study are available at the Department of Urology, The University of Tokyo Hospital.

Authors’ contributions

YY collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. TF collected the data, assisted in designing the study, and also assisted on writing the manuscript. HF, TN, and HK collected the data and assisted in designing the study. TS assisted on statistical analysis. KT, SK, and MS collected the data and assisted in the statistical analysis. YI and YH assisted in the design of the study and made important suggestions in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the “Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital” (#2283), and written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, Y., Fujimura, T., Fukuhara, H. et al. Incidence and risk factors of inguinal hernia after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. World J Surg Onc 15, 61 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1126-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1126-3