Abstract

Background

In practice, small bowel cancer is a rare entity. The most common histologic subtype is adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel (SBA) is challenging to diagnose, often presents at a late stage and has a poor prognosis. The treatment of early-stage SBA is surgical resection. No standard protocol has been established for unresectable or metastatic disease.

Case presentation

We report here on a 26-year-old man with SBA in the jejunum, lacking specific symptoms and with a delay of 6 months in diagnosis. The diagnosis was finally achieved with a combination of balloon-assisted enteroscopy, computed tomography scans, positron emission computed tomography scans and the values of carcino-embryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9. The patient underwent segmental intestine with lymph node resection, followed by eight cycles of FOLFOX palliative chemotherapy with good tolerance. As of the 11-month postoperative follow-up, there has been no evidence of recurrent disease.

Conclusions

This case is reported to arouse a clinical suspicion of SBA in patients with abdominal pain of unknown cause. We also provided evidence in this case of a response to palliative chemotherapy with FOLFOX. Because the incidence of SBA is very low, there is a need for further studies to evaluate the possible application of newer investigative agents and strategies to obtain a better outcome within the framework of international collaborations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

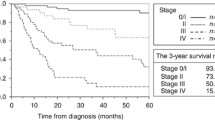

Small bowel cancer is a rare malignancy that comprises less than 5 % of all gastrointestinal malignancies. The estimated annual incidence is 0.3–2.0 cases per 100,000 persons, with a higher prevalence rates in the black population than the white, and has been recently increasing [1, 2]. It is most frequently diagnosed among people aged 55–64, with the incidence increasing after age 40. The current 5-year survival rate in the USA is 65.5 %; cancer stage at diagnosis has a strong influence on the length of survival [3].

Small bowel cancer has four common histological types: adenocarcinoma (30–40 %), carcinoid tumour (35–42 %), lymphoma (15–20 %), and sarcoma (10–15 %) [4]. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel (SBA) is most commonly located in the duodenum (57 %), while 29 % of cases are located in the jejunum and 10 % in the ileum [5]. Clinical presentation of SBA is nonspecific abdominal discomfort, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding and intestinal obstruction, which leads to an average delay of 6–10 months in diagnosis [6]. Due to the rarity of this cancer, there have been no good screening methods developed for SBA; little is known about the clinical characteristics, treatment modalities or prognosis of patients with SBA, especially in Asians.

Here, we report on a 26-year-old man with SBA in the jejunum, without specific symptoms. He was diagnosed until he had an incomplete small bowel obstruction, with a delay of 6 months in diagnosis. Segmental intestine with lymph node resection was performed, followed by eight cycles of FOLFOX palliative chemotherapy. The patient was doing well as of his last follow-up.

Case presentation

The patient was male, 26 years old and had no specific underlying or family disease. Six months ago, he experienced an episodic attack of distending pain in his left lower quadrant, nausea and vomiting; he was treated with oral drugs at a local hospital. However, his symptoms were not completely relieved, and were later aggravated. A normal abdominal X-ray suggested incomplete small bowel obstruction. He was admitted to our hospital.

The patient visited our hospital without any complaints. Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with tenderness in the left lower quadrant. No mass was palpated in the abdomen. When his abdominal pain occurred, a peristaltic wave could be observed around the navel. Laboratory tests showed no anaemia or leukocytosis. Examination of tumour-associated antigens showed a prominent high levels of carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) at 29.17 ng/ml and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) at 970.3 U/ml. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans showed many swollen lymph nodes adjacent to the abdominal aorta in the retroperitoneal space (Fig. 1) but no discernible mass. Positron emission computed tomography (PET)/CT scans revealed abnormal accumulations of 18F-FDP in many stiffening intestinal segments and also in many retroperitoneal swollen lymph nodes, indicating hypermetabolism disease, with a high possibility of a malignant disease (Fig. 2). Gastroscopy and enteroscopy showed that the stomach, colon and rectum were normal. However, double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) and the following biopsy revealed at the upper jejunum that most of the lumen was obstructed by an irregular protrusive tumour of gastrointestinal origin (Fig. 3a).

Because of the symptoms of intestinal obstructions and a high possibility of advanced stage, the patient underwent segmental resection of the jejunum. At laparotomy, a 5 × 5 cm round mass with no distinct boundary was present at the jejunum (25 cm from the ligament of Treitz). The mass involved the entire wall of the small intestine and directly invaded the neighbouring mesentery. There were many enlarged lymph nodes around the superior mesenteric vein and the first and second jejunal arteries in the involved mesentery. There was no evidence of metastatic lesions in the peritoneum or liver during intraoperative inspection of all quadrants of the abdominal cavity. We performed a radical resection with 40 cm of the jejunum and the involved mesentery, vessels and lymph nodes (Fig. 3b, c). Pathologic examination revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with metastasis to seven out of 14 resected lymph nodes (Fig. 4); free surgical margins were achieved. The tumour was staged as T4N2M0, stage IIIB disease [7]. Genetic studies of the specimen revealed that it had low expression of thymidylate synthase (TS) and excision repair cross-complementing gene 1 (ERCC1), sensitive to fluoropyrimidine and platinum [8]. He was started on palliative chemotherapy with FOLFOX for a total of eight cycles. He tolerated chemotherapy well, and the values of CEA and CA 19-9 decreased gradually as the chemotherapy progressed (Fig. 5a). CT scans also showed that the swollen lymph nodes adjacent to the abdominal aorta were significantly lessened (Fig. 5b). As of the 11-month postoperative follow-up, there has been no evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Whereas the small bowel represents 75 % of the length of the digestive tract and 90 % of the absorptive mucosal surface area, tumour of the small bowel is rarer than other gastrointestinal malignancies. The possible explanations include the high levels of IgA and the more rapid transit in the small bowel compared to the large bowel. Little bacteria and more sensitivity to stress in the small bowel also contribute to the low tumour incidence [9]. Though small bowel cancer normally occurs in elderly patients [3], in this case, it was found in a 26-year-old young man. The mass remained undetectable until he had an incomplete small bowel obstruction with lymph node metastasis. This was similar with studies, in which diagnosis of SBA was mainly obtained at advanced stages; ~40 % of patients have lymph node metastasis (stage III), and 35 to 40 % have distant metastasis (stage IV) [6, 10].

The symptoms of SBA are initially nonspecific abdominal discomfort; diagnosis is delayed and usually in the context of emergency involving an occlusion (40 %) or bleeding (24 %) [6], which is similar to the presentation of our patient. For diagnosis of SBA, CT scans have an overall accuracy rate of 47 % [11]. While CT scans can detect the lesions, they cannot provide precise data of the intestinal mucosa and miss some small or flat lesions. The PET/CT technique is being used to differentiate small intestinal malignant tumours from benign ones. The uptake of 18F-FDG is related to tumour size, infiltration and lymph node metastasis; the higher the uptake of 18F-FDG, the higher the tumour invasiveness [12]. Gastroscopy and enteroscopy can be appropriate if the tumour is located close to the proximal duodenum or far from the terminal ileum. The rest of the small bowel cannot be accessed without the use of video capsule endoscopy (CE) or DBE. The definite diagnostic yield of CE is only 20–30 %, while DBE accounts for 60–70 % of the diagnostic yield for intestinal diseases [13]. However, CE is suitable for diagnosing scattered, small and multiple lesions, as well as active bleeding; it is convenient, non-invasive, secure and comfortable. In contrast, the DBE procedure is uncomfortable, less tolerated and difficult to complete; these factors influence its diagnosis [13]. A baseline plasmatic CEA and CA 19-9 assay is necessary, especially in cases of advanced disease because CEA and CA 19-9 levels are of prognostic value [14]. In this case, the diagnosis was achieved by the combination of the DBE results, CT images, PET/CT images and the values of CEA and CA 19-9.

Surgical resection with clear margins and regional lymph node resection remains the treatment of choice in localized SBA; indeed, it is often required even in metastatic SBA due to the high probability of obstruction or severe haemorrhage [15]. To date, there has been no standard chemotherapy regimen against SBA. Several studies have explored the role of palliative chemotherapy in advanced SBA. Hong et al. [16] have shown in stage IV patients who received palliative chemotherapy that overall survival (OS) increased significantly compared to those who did not receive chemotherapy (8 vs. 3 months, p = 0.025). Ecker et al. [17] have shown that median OS was superior for patients with resected stage III SBA who were receiving chemotherapy versus those who were not (42.4 vs 26.1 months, p < 0.001). As for the Asian population, Mizyshima et al. [18] showed that, in patients with non-curative resection or unresectable distant metastasis, the response rate to chemotherapy was 31.6 %, and the 3-year OS rate was significantly higher compared to the response rate without chemotherapy (26.3 vs. 13.8 %; p = 0.008). Several chemotherapy drugs have also been evaluated in the treatment of metastatic SBA. Zaanan et al. [14] have shown that the median OS in advanced SBA patients treated with FOLFOX was 17.8 months, the longest survival among different chemotherapy regimens. Two phase II studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of different chemotherapy regimens in advanced SBA: the response rates were around 50 %, the median progression-free survivals 7.8 and 11.3 months and the median OS 15.2 and 20.4 months [19, 20]. Newer agents, such as endothelial growth receptor (EGFR) antibody drugs, and newer combinations are being explored as the second line for improved treatment of advanced SBA [21]. From limited clinical reports, a combination of fluoropyrimidine with platinum compounds (FOLFOX or CAPOX) has been proposed as the first-line treatment for palliative chemotherapy in metastatic SBA treatment [22]. In view of the results of genetic studies, the patient underwent palliative chemotherapy for eight cycles of FOLFOX and was doing well as of his last follow-up.

Conclusions

We report a rare case of jejunum adenocarcinoma in a young man in China. Diagnosis of SBA remains a challenge. A physician’s suspicion and awareness is crucial in patients with abdominal pain of unknown cause. Patients with delayed diagnosis often have a poorer prognosis. Surgery remains the primary treatment. In this case, we noticed a response to palliative chemotherapy with FOLFOX. Because the incidence of SBA is very low, there is a need for further studies to evaluate the possible application of newer investigative agents and strategies to obtain a better outcome within the framework of international collaborations.

Abbreviations

CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA, carcino-embryonic antigen; CT, computed tomography; DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy; ERCC1, excision repair cross-complementing gene 1; PET, positron emission tomography; SBA, adenocarcinoma of the small bowel; TS, thymidylate synthase

References

Haselkorn T, Whittemore AS, Lilienfeld DE. Incidence of small bowel cancer in the United States and worldwide: geographic, temporal, and racial differences. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:781–7.

Shack LG, Wood HE, Kang JY, Brewster DH, Quinn MJ, Maxwell JD, Majeed A. Small intestinal cancer in England and Wales and Scotland: time trends in incidence, mortality and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1297–306.

SEER cancer statistics factsheets: small intestine cancer. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/ststfacts/html/smint.html

Pan SY, Morrison H. Epidemiology of cancer of the small intestine. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:33–42.

Halfdanarson TR, McWilliams RR, Donohue JH, Quevedo JF. A single institution experience with 491 cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2010;199:797–803.

Dabaja BS, Suki D, Pro B, Bonnen M, Ajani J. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: presentation, prognostic factors, and outcome of 217 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:518–26.

Gleason D, Miller-Hammond KE, Gibbs JF. Small bowel cancer. In: Surgical oncology: a practical and comprehensive approach. New York: Springer; 2015. p. 217–34.

Kumamoto K, Ishibashi K, Ishida H. Predictive marker for the efficacy of FOLFOX treatment in colon cancer (TS, ERCC1 etc.). Nihon Rinsho. 2011;69 Suppl 3:494–9.

Speranza G, Doroshow JH, Kummar S. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: changes in the landscape? Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:387–93.

Talamonti MS, Goetz LH, Rao S, Joehl RJ. Primary cancers of the small bowel: analysis of prognostic factors and results of surgical managements. Arch Surg. 2002;137:564–70.

Horton KM, Fishman EK. The current status of multidetector row CT and three-dimensional imaging of the small bowel. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:199–212.

Cronin CG, Scott J, Kambadakone A, Catalano OA, Sahani D, Blake MA, McDermott S. Utility of position emission tomography/CT in the evaluation of small bowel pathology. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1211–21.

Zhang ZH, Qiu CH, Li Y. Different roles of capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in obscure small intestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7297–304.

Zaanan A, Costes L, Gauthier M, Malka D, Locher C, Mitry E, Tougeron D, Lecomte T, Gornet JM, Sobhani I, Moulin V, Afchain P, Taïeb J, Bonnetain F, Aparicio T. Chemotherapy of advanced small-bowel adenocarcinoma: a multicenter AGEO study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1786–93.

Apaicio T, Zaanan A, Svrcek M, Laurent P, Carrere N, Manfredi S, Locher C, Afchain P. Small bowel adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Digest liver dis. 2014;46:97–104.

Hong SH, Koh YH, Rho SY, Byun JH, Oh ST, Im KW, Kim EK, Chang SK. Primary adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: presentation, prognostic factors and clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:54–61.

Ecker BL, McMillan MT, Datta J, Mamtani R, Giantonio BJ, Dempsey DT, Fraker DL, Drebin JA, Karakousis GC, Roses RE. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for small bowel adenocarcinoma: a propensity score-matched analysis. Cancer. 2016;122:693–701.

Mizushima T, Tamagawa H, Mishima H, Ikeda K, Fujita S, Akamatsu H, Ikenaga M, Onishi T, Fukunaga M, Fukuzaki T, Hasegawa J, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Yamamoto H, Sekimoto M, Nezu R, Doki Y, Mori M. The effects of chemotherapy on primary small bowel cancer: a retrospective multicenter observational study in Japan. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:820–4.

Overman MJ, Varadhachary GR, Kopetz S, Adinin R, Lin E, Morris JS, Eng C, Abbruzzese JL, Wolff RA. PhaseIIstudy of capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced adenocarcinoma of the small bowel and ampulla of Vater. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2598–603.

Xiang XJ, Liu YW, Zhang L, Qiu F, Yu F, Zhan ZY, Feng M, Yan J, Zhao JG, Xiong JP. A phaseIIstudy of modified FOLFOX as first-line chemotherapy in advanced small bowel adenocinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:561–6.

De Dosso S, Molinari F, Martin V, Frattini M, Saletti P. Molecular characterization and cetuximab-based treatment in a patient with refractory small bowel adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2010;59:1587–8.

Zaaimi Y, Aparicio T, Laurent-Puig P, Taieb J, Zaanan A. Advanced small bowel adenocarcinoma: molecular characteristics and therapeutic perspectives. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:154–60.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Pro. Li Lu (Department of gastroenterology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center) who provided the data of the imaging technique and endoscopy.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant to J. Li from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81172358).

Availability of data and materials

The availability of the data and material section concerning the case report is related to all the diagnostic examinations that the patients have submitted during their hospitalization. The publication of all these data has been authorized by the Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center.

Authors’ contributions

XX and LJ designed the study; LJ analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; LN and HJF collected the data and presented the clinical features; XX, LJ and WZL performed the operation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The consent for publication of the manuscript and the related images from the patients and/or their relatives has been obtained by the Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical approval has been received by the medical ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center concerning the publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images. A copy of this document is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

New software

The authors declare that no new software has been used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wang, Z., Liu, N. et al. Small bowel adenocarcinoma of the jejunum: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Onc 14, 177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0932-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0932-3