Abstract

Background

Attitude towards condom use is an important predictor of consistent condom use. However, this topic is an understudied area in Chinese populations, and no validated Chinese instrument is available to capture condom attitude. To fill this research gap, the present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Multidimensional Condom Attitudes Scale (MCAS) and assessed the attitudes towards condom use amongst Chinese adults aged 18–29 years old.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 500 people aged 18–29 years old were randomly recruited in Hong Kong. The primary outcome was the attitude towards condom use as measured by the UCLA MCAS. Factor structure, internal construct validity, known-group validity and internal consistency were assessed.

Results

Instead of the five-factor structure designed by the original developers of the MCAS questionnaire, this study proposed a novel six-factor scale: (1) Reliability and Effectiveness, (2) Excitement, (3) Displeasure, (4) Identity Stigma, (5) Embarrassment about Negotiation and (6) Embarrassment about Purchase. The internal construct validity and reliability of the new scale were high. The revised MCAS could differentiate between subgroups, including gender, sexual orientation and sexual experience. In terms of attitudes, over 40% of the participants believed that condoms are not reliable, though the vast majority of the sample did not perceive any stigma related to condom use. In addition, more than half (55.4%) of the respondents felt embarrassed to be seen when buying condoms while a quarter (25.8%) felt uncomfortable buying condoms at all.

Conclusions

Overall, the psychometric analysis found that attitude to condom use is culturally specific. The study also highlighted the need for more public health campaigns and interventions to help people cope with the embarrassment of purchasing condoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remain a severe global health issue. China, including Hong Kong, is experiencing a rapid increase in HIV/AIDS [1, 2]. A population-based study of 18–26 year olds in Hong Kong found that chlamydia is relatively common in sexually active women (5.8%) and men (4.8%) [3]. The increasing popularity of smartphone online dating and a growing openness towards premarital sex and homosexual relationships have resulted in an increased prevalence of STIs [4,5,6,7]. It should also be noted that Hong Kong is an important global city with a population of 7.3 million people [3], and the number of visitors to the region continues to rise. A systematic meta-analysis recently reported that the prevalence of travel-associated casual sex (tourists having sex with local people) could be as high as 20%, with 49.4% of these cases involving unprotected intercourse [8]. This phenomenon could be a contributing factor to the increase in STIs in the local community. To diminish the negative impact of STIs, their primary prevention is very important, especially amongst high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men, young people and sex workers.

An essential method of reducing the spread of STIs is consistent condom use. Meta-analyses have reported that consistent condom use can reduce the risk of HIV infection by 80–95% [9, 10]. Condom use is likewise associated with statistically significant protection of men and women against several types of STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhoea, herpes simplex virus type 2 and syphilis [11]. Although analyses have shown that different interventions, including behavioural [12] and technology-based [13] approaches, can increase condom usage, inconsistent condom use is still found in different Chinese populations [5, 14]. Moreover, findings from a series of behavioural surveillance surveys from 1998 to 2015 showed no evident improvement in consistent condom use in Hong Kong [15]. Hence, there is an urgent need to further understand the barriers and facilitators of condom use to diminish the spread of STIs.

Understanding the predictors of condom use is key to developing effective interventions and community programmes to increase condom use. Attitude is an important factor in nearly all health behaviour models [16]; specifically, existing evidence suggests that attitude towards using condoms is a strong predictor of their use [17, 18]. Moreover, interventions that do not address attitude often fail to improve safe sexual behaviours [19]. Accordingly, understanding and enhancing a positive attitude towards the use of condoms are of paramount importance to achieve consistent condom use. These will, in turn, help reduce the spread of STIs.

Need for the present study

Despite the importance of understanding the attitude towards condom use, this area is understudied in Chinese populations, including Hong Kong. Study findings obtained in other populations are not necessarily generalisable to Chinese populations because sexual health-related attitude, including attitude towards condom use, is not universal but is influenced instead by the social and cultural norms in each context [20, 21]. A classic example is the opposition of the Roman Catholic Church to the use of artificial contraception, including condoms [22]. Besides, sexual health attitudes are not static and can change generationally [23]. To further enhance sexual health, diminish the adverse impact of non-condom use amongst Chinese populations and develop tailored intervention for specific populations [24], up-to-date information about attitudes towards condom use amongst Chinese population is therefore required.

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Multidimensional Condom Attitudes Scale (MCAS) is a questionnaire developed to assess the attitude towards condom use [25]. The questionnaire was originally developed for use amongst college students in the United States [25] and subsequently validated in different populations, such as low-acculturated Hispanic women [26] and Black South African university students [27]. However, the psychometric properties of the UCLA MCAS have not been validated in Chinese populations. Therefore, to address these research gaps and provide additional information about attitudes towards condom use in Chinese populations, the present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric performance of the MCAS in young Chinese adults as well as their attitudes to condom use.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Hong Kong.

Subjects

Mobile phone numbers in Hong Kong were randomly sampled by an independent research organisation, and invitations to participate in the survey were sent by text message to the sampled numbers. Mobile sampling instead of landline sampling was adopted in this study because of the rapidly increasing number of households without landline and the growing concerns about the representativeness of samples selected using landline random digit dialling sampling frames [28]. A person eligible to join the study should (1) be aged between 18 and 29 years old, (2) be able to read Chinese, (3) have a mobile phone and (4) have Internet access. People were excluded if they were not willing to join the study.

Study instruments

The UCLA MCAS [25] was used in the present study for the following reasons. First, the MCAS was developed amongst young people with a mean age of 19, similar to the population in the present study (the mean age of study participants was 21.2). Second, the development of the MCAS involved people both with and without sexual experience [25], meaning the instrument is not limited to sexually active individuals. Therefore, this instrument was suitable to be used in the current study sample, which was composed of people with and without sexual experience. Third, the ability of MCAS to assess multiple components of attitude is important because attitude towards condom use is multidimensional in nature [18]. The original MCAS is a 25-item instrument arranged across five factors: (1) reliability and effectiveness of condoms, (2) sexual pleasure associated with condom use, (3) stigma attached to those who use condoms, (4) embarrassment about condom use negotiation with sexual partners and (5) embarrassment about condom purchase [25]. Using the MCAS, participants were asked to respond to a seven-point Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude towards condom use.

Demographic information, including age, gender, sexual orientation and sexual experience, were also collected.

Data analysis

To carry out psychometric analysis of the MCAS, the factor structure, internal construct validity, known-group validity and reliability of the scale were evaluated. Data were fitted to the five-factor model proposed by the original authors [25] and the revised five-factor model by Starosta et al. [18]. However, the data did not fit either of these models. Consequently, the data were split into training (n = 250) and test (n = 250) sets [29]. The training set was used in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with promax rotation of factors with eigenvalues of > 1.0. A scree plot of the EFA was also used to determine the number of latent factors. The appropriateness of the factor analysis was examined using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index of sampling adequacy. Bartlett’s test is a measure of the probability that the initial correlation matrix is an identity matrix; to recommend the suitability of the EFA, the p value of Bartlett’s test must be lower than 0.05 and the KMO value must be greater than 0.7 [30]. Individual items with a factor loading of ≥ 0.5 were assigned to that factor. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then tested using the weighted least squares mean and variance that accounted for the categorical nature of the items. Criteria for an acceptable fit were a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of < 0.06, a comparative fit index (CFI) of ≥ 0.90 and a Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) of ≥ 0.90 [31, 32].

Internal construct validity was evaluated using the corrected item-total correlation. A correlation coefficient of ≥ 0.4 was considered an adequate correlation [33]. To evaluate known-group validity, the domain scores were compared by an independent t test between (1) male and female respondents, (2) heterosexual and bi- or homosexual participants and (3) people with and without sexual experience. Cohen’s d effect sizes were also calculated and interpreted as either trivial (< 0.2), small (≥ 0.2 and < 0.5), moderate (≥ 0.5 and < 0.8) or large (≥ 0.8) [34]. The internal consistency of the scale was evaluated by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, in which a value of ≥ 0.7 was considered to be adequate internal consistency [33].

Sample size justification

Based on previous guidelines, a sample size of at least 200 people is needed for EFA [35]. In the present study, a total of 500 participants were included in the analysis. This sample size was enough to conduct both EFA (n = 250) and CFA (n = 250).

Results

Participant characteristics

Five hundred participants were recruited and completed the online survey. Their mean age was 21.2 years (standard deviation: 2.88), 60.0% were female, 87.4% were heterosexual and 40.0% received tertiary or higher education. Table 1 presents the demographic information of the study participants.

Factor analysis and internal consistency

Bartlett’s test for the significance of the correlation matrix was 2437.79 (p value < 0.001), indicating the appropriateness for factor analysis. Sample adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.74, which exceeded the minimum adequacy of 0.50. Principal axis factoring suggested a six-factor structure, accounting for 50.67% of the variance (12.67% by factor 1 ‘Reliability and Effectiveness’, 12.56% by factor 2 ‘Embarrassment about Purchase’, 11.26% by factor 3 ‘Identity Stigma’, 6.41% by factor 4 ‘Embarrassment about negotiation’, 4.32% by factor 5 ‘Excitement’, and 3.45% by factor 6 ‘Displeasure’. Items 6 and 20 returned factor loadings of < 0.5 and did not, therefore, load on any factors, meaning they were removed. Table 2 shows the results of the EFA.

The CFA provided an RMSEA of 0.056, a CFI value of 0.96 and a TLI value of 0.95. These goodness-of-fit indices indicated that the data fit the six-factor model. Table 3 shows the CFA results. The factor structure is shown in Additional file 1: Figure 1. The item-total correlations for overlap were > 0.4 for all items, except for item 23. The results are presented in Table 4.

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was > 0.7 in five of the six subscales while only 0.65 for Displeasure. The results are shown in Table 4.

Known-group validity

First, the subscale scores of males and females were compared by an independent t test. A statistically significant difference was found in the subscales for Reliability and Effectiveness (effect size = 0.28; p value < 0.01), Identity Stigma (effect size = 0.22; p value = 0.02), Embarrassment about Negotiation (effect size = 0.19; p value = 0.03) and Embarrassment about Purchase (effect size = 0.68; p value < 0.01). Second, the subscale scores of heterosexual and bi- or homosexual participants were compared, and three subscales showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups. These differences were in Reliability and Effectiveness (effect size = 0.35; p value = 0.01), Displeasure (effect size = 0.31; p value = 0.02) and Embarrassment about Negotiation (effect size = 0.42; p value < 0.01). Third, the subscale scores were compared between participants with and without sexual experience and statistically significant differences were found in the following subscales: Reliability and Effectiveness (effect size = 0.28; p value = 0.01), Displeasure (effect size = 0.45; p value < 0.01), Embarrassment about Negotiation (effect size = 1.17; p value < 0.01), and Embarrassment about Purchase (effect size = 0.40; p value < 0.01). The complete results are shown in Table 5.

Attitude towards condom use in young Chinese adults

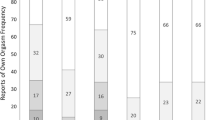

Slightly more than half of the participants agreed that condoms are an effective (58.2%) and satisfactory (55.4%) method of contraception, while more than 40% thought they are unreliable. A total 65% of the respondents felt that using condoms is uncomfortable or ruins sexual intercourse. Only a few participants perceived stigma attached to the use of condoms (2.6–5.4%). More than half of the participants did not feel embarrassed about negotiating condom use. However, more than half of the participants felt embarrassed to be seen buying condoms, while a quarter felt uncomfortable about buying them at all. The results are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

This study established the validity and reliability of using the UCLA MCAS with young Chinese adults. However, the initial exploratory factor analysis suggested that the data obtained from the current Chinese population did not fit the structure found in western populations. For example, a previous study on Colombian men and women [36] and low-acculturated Hispanic women [26] replicated the original five-factor structure. Thus, the results suggested that condom use attitude is culturally specific. Related to this, previous studies have found that differences in race and ethnicity influence perceptions about condom use amongst African Americans and Caucasians [37] and the level of unwanted condom use amongst African Americans, Latinos and Caucasians [38]. This result has implications for the findings of the present study. First, interventions to promote positive attitudes towards condom use should be culture-specific [39] because health promotion strategies that are effective in western contexts may not necessarily transfer to Chinese populations. Second, from a psychometric perspective, caution is required when comparing attitude measured by the MCAS across other cultures given the difference in factor structure. Further studies are warranted to investigate any measurement invariance of this particular instrument across different cultures to ensure that the comparison of instrument scores is valid and meaningful [18]. Nevertheless, similar to the validation study on Colombian men and women [36], the present study also found that men have more positive attitudes towards the reliability and effectiveness of condoms and are less embarrassed by condom negotiation and use. This finding implies that further education to enhance female’s attitude towards the effectiveness of condoms and improve their skills in condom use negotiation is needed.

On the basis of the EFA result, items 6 (‘The use of condoms can make sex more stimulating’) and 20 (‘I never know what to say when my partner and I need to talk about condoms or other protection’) were excluded in the current study. This outcome is consistent with that suggested by Starosta et al. [18], who found that these two items functioned differently between the genders and should be removed from the scale. Item 6 was recommended for removal from the scale because it cannot accurately represent female attitudes towards condom use, thus possibly biasing the result obtained from this subscale [18]. Regarding item 20, Starosta et al. [18] pointed out that sexually active heterosexual women must have considerably more favourable attitudes about discussing the use of condoms than do men. Thus, the inclusion of item 20 in the scale might inflate the score in females compared to that in males [18].

Purchasing condoms was found to be far more embarrassing than condom use negotiation in a Chinese population. Specifically, approximately 25% of the participants said they would feel uncomfortable buying condoms, and more than half expressed embarrassment at being seen buying them. By contrast, only 10% of the participants felt it would be difficult to discuss condom use with their partner. Individuals may feel embarrassed about purchasing condoms because it involves a social audience and public behaviour but not about using condoms where the interaction is with just one other person [40]. A study in North America found that purchasing condoms elicits the most embarrassment, whereas using condoms is the least embarrassing [40]. A further study conducted in China, Canada and South Korea similarly found that the embarrassment associated with purchasing condoms exceeds that of using condoms [41]. Note that embarrassment about purchasing condoms impact purchase intent, which in turn significantly reduces the frequency of condom use [41, 42].

This finding has several implications. First, further discussions about this embarrassment and suggestions about how to cope with it are required in sexual health education [41]. Current sexual health education in Hong Kong and initiatives relating to condom use largely focus on the importance of using condoms, the right way to use them and their effectiveness. However, topics related to embarrassment and purchasing behaviours are neglected. Therefore, purchase-related embarrassment and the strategies to cope with it must be considered in sexual health education in order to promote consistent condom use and improve sexual and reproductive health worldwide [41]. Second, the process of obtaining condoms should be improved and made less embarrassing [42]. Undoubtedly, purchasing condoms online is less embarrassing. However, individuals cannot obtain them immediately, and this is particularly relevant to the context of casual sex in which people need condoms instantly. In Hong Kong, condoms are mainly available in convenience stores, supermarkets and pharmacies, but those who are worried about being seen may not wish to buy condoms from such shops. Vending machines for condoms are available but not very common, and so a possible solution is to place more of these machines in public—but relatively private—places, such as public toilets. Fundamentally, more public health campaigns and sexual health education to help cope with embarrassment about purchasing condoms are required [41].

Perhaps surprisingly, the concept of condom reliability and effectiveness was suboptimal in the present study. Only approximately half of the participants agreed that condoms were an effective and satisfactory method of birth control while more than 40% expressed concerns over their reliability. A related research from Singapore found that 42.1% of the adolescents studied had experienced condom slippage and 32.1% had experienced breakage [43]. A negative attitude towards reliability and effectiveness and a fear of upsetting consequences are probable reasons for the high prevalence of inconsistent condom use in the Hong Kong community [5, 44, 45], and these have implications for the findings. First, qualitative studies are required to explore why people think condoms are unreliable and/or ineffective. Second, individuals should be taught how to choose the correct condom size as well as how to use condoms properly to enhance their reliability and effectiveness in birth control and STI prevention.

A moderate gender difference in embarrassment about condom purchase was found. In line with previous studies in China [41] and the United States [46], female participants were more embarrassed about purchasing condoms than do their male counterparts. A potential reason for this greater degree of embarrassment is because ‘a female is purchasing a male method of contraception’ [47]. Other possible reasons in this population are that sex is still largely taboo in Chinese culture and the existence of gender inequality. For example, Chinese people tend to highlight the importance of premarital sexual abstinence for girls rather than for boys [48], a propensity that is likely to make females more embarrassed about buying condoms than do males. In addition to these gender differences, variance in embarrassment about negotiating condom use across sexual orientations was found, with non-heterosexual respondents more embarrassed than their heterosexual counterparts. An explanation for this may be related to psychological and social factors, such as anxiety, loneliness or distress associated with sexual identity [49]. Disparity in the rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) may also lead to this difference. IPV has been shown to be more prevalent in some non-heterosexual groups than in heterosexual populations [50, 51] and suggested to be capable of lowering the efficacy of condom negotiation [52]. Future interventions aimed at enhancing attitude towards condom use should account for the differences in gender and sexual orientation.

Different levels of embarrassment about negotiating condom use were found between participants who had sexual experience and those who did not. Sexually inexperienced people felt more embarrassed about discussing condom use with their partner and buying condoms in the first place. A possible explanation here is that embarrassment about negotiation and purchase is a barrier to initiating sexual activities amongst young adults. However, these associations should be interpreted with caution because causality cannot be inferred from this limited cross-sectional analysis. Thus, further longitudinal studies are needed to explore the temporal relationship between embarrassment and experience.

The present study has some limitations. First, given its cross-sectional nature, the test–retest reliability and responsiveness of the instrument could not be assessed, and further studies are required to establish the psychometric properties. Second, all participants were aged between 18 and 29 years old. Therefore, the findings may not be generalisable to a wider population. That said, the intention of the current study was to study this subgroup specifically because it was previously found that inconsistent condom use is common within it [5]. For example, young adults are more sexually adventurous than older adults [53]. Furthermore, STIs, including chlamydia, are reported to be highly prevalent in this subgroup of the Hong Kong community [3]. Third, given that only attitude towards condom use was measured, other aspects, such as knowledge, self-efficacy and sexual behaviour, should be included in future studies to investigate their relationships with this attitude.

Conclusion

The validity and reliability of the MCAS were evaluated in young Chinese adults. Instead of the five-factor structure developed in previous studies, a six-factor scale was found, suggesting that condom attitudes are culturally specific. High levels of embarrassment about purchasing condoms and negative attitudes towards their reliability and effectiveness were reported, implying that future health interventions regarding condom use must focus on these inadequately promoted areas.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available because it contains personal data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- KMO:

-

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- MCAS:

-

Multidimensional Condom Attitudes Scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis index

References

Liu Z, Wei P, Huang M, Bao Liu Y, Li L, Gong X, Chen J, Li X. Determinants of consistent condom use among college students in China: application of the information-motivation-behavior skills (IMB) model. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108976.

Wang Z, Lau JT, Fang Y, Ip M, Gross DL. Prevalence of actual uptake and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, China. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0191671.

Wong WC, Zhao Y, Wong N, Parish WL, Miu HY, Yang L, Emch M, Ho K, Fong FY, Tucker JD. Prevalence and risk factors of chlamydia infection in Hong Kong: a population-based geospatial household survey and testing. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172561.

Ghebremichael MS, Finkelman MD. The effect of premarital sex on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and high risk behaviors in women. J AIDS HIV Res. 2013;5(2):59.

Choi EP, Wong JY, Lo HH, Wong W, Chio JH, Fong DY. The impacts of using smartphone dating applications on sexual risk behaviours in college students in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE. 2016a;11(11):e0165394.

Choi EP, Wong JY, Lo HH, Wong W, Chio JH, Fong DY. The association between smartphone dating applications and college students’ casual sex encounters and condom use. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016b;9:38–41.

Stolte IG, Dukers NH, de Wit JB, Fennema JS, Coutinho RA. Increase in sexually transmitted infections among homosexual men in Amsterdam in relation to HAART. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(3):184–6.

Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter P. Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e842–51.

Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(9):1303–12.

Weller SC, Davis-Beaty K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003255.

Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:454–61.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to increase condom use and reduce sexually transmitted infections: a meta-analysis, 1991 to 2010. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(5):489.

Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. Aids. 2009;23(1):107–15.

Wang Z, Yang L, Jiang H, Huang S, Palmer AE, Ma L, Lau JT. High prevalence of inconsistent condom use with regular female sex partners among heterosexual male sexually transmitted disease patients in Southern China. J Sex Marital Therapy. 2019;45:1–13.

Li J, Lau JT, Ma YL, Lau MM. Trend and factors associated with condom use among male clients of female sex workers in Hong Kong: findings of 13 serial behavioural surveillance surveys. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(7):2235–47.

Senn TE, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP. Relationship-specific condom attitudes predict condom use among STD clinic patients with both primary and non-primary partners. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(8):1420–7.

Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(1):90.

Starosta AJ, Berghoff CR, Earleywine M. Factor structure and gender stability in the multidimensional condom attitudes scale. Assessment. 2015;22(3):374–84.

Kajubi P, Kamya MR, Kamya S, Chen S, McFarland W, Hearst N. Increasing condom use without reducing HIV risk: results of a controlled community trial in Uganda. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(1):77–82.

Kocken P, Van Dorst A, Schaalma H. The relevance of cultural factors in predicting condom-use intentions among immigrants from the Netherlands Antilles. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(2):230–8.

Lazarus J, Moghaddassi M, Godeau E, Ross J, Vignes C, Östergren P-O, Liljestrand J. A multilevel analysis of condom use among adolescents in the European Union. Public Health. 2009;123(2):138–44.

Benagiano G, Carrara S, Filippi V, Brosens I. Condoms, HIV and the roman catholic church. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22(7):701–9.

Techasrivichien T, Darawuttimaprakorn N, Punpuing S, Musumari PM, Lukhele BW, El-saaidi C, Suguimoto SP, Feldman MD, Ono-Kihara M, Kihara M. Changes in sexual behavior and attitudes across generations and gender among a population-based probability sample from an urbanizing province in Thailand. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(2):367–82.

Choi EP, Chow EP, Wan EY, Wong WC, Wong JY, Fong DY. The safe use of dating applications among men who have sex with men: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate an interactive web-based intervention to reduce risky sexual behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–7.

Helweg-Larsen M, Collins BE. The UCLA multidimensional condom attitudes scale: documenting the complex determinants of condom use in college students. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):224.

Unger JB, Molina GB. The UCLA multidimensional condom attitudes scale: validity in a sample of low-acculturated Hispanic women. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1999;21(2):199–211.

Madu SN, Peltzer K. Factor structure of condom attitudes among Black South African university students. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2003;31(3):265–74.

Jackson AC, Pennay D, Dowling NA, Coles-Janess B, Christensen DR. Improving gambling survey research using dual-frame sampling of landline and mobile phone numbers. J Gambl Stud. 2014;30(2):291–307.

Wong JY, Fong DY, Yau JH, Choi EP, Choi AW, Brown JB. Using the woman abuse screening tool to screen for and assess dating violence in college students. Violence Against Women. 2018;24(9):1039–51.

Goto F, Tsutsumi T, Ogawa K. The Japanese version of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory as an index of treatment success: exploratory factor analysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(8):817–25.

Lt Hu. Bentler PM: cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Chin WY, Choi EP, Chan KT, Wong CK. The psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in Chinese primary care patients: factor structure, construct validity, reliability, sensitivity and responsiveness. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135131.

Choi EP, Lam CL, Chin W-Y. Validation of the International Prostate Symptom Score in Chinese males and females with lower urinary tract symptoms. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):1.

Rosenthal JA. Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. J Soc Serv Res. 1996;21(4):37–59.

Jung S, Lee S. Exploratory factor analysis for small samples. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43(3):701–9.

Plaza-Vidal R, Ibagon-Parra M, Vallejo-Medina P: Spanish translation, adaptation, and validation of the multidimensional condom attitudes scale with young colombian men and women. Archiv Sex Behav. 2020:1–12.

Johnson EH, Jackson LA, Hinkle Y, Gilbert D, Hoopwood T, Lollis CM, Willis C, Gant L. What is the significance of black-white differences in risky sexual behavior? J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(10):745.

Smith LA. Partner influence on noncondom use: gender and ethnic differences. J Sex Res. 2003;40(4):346–50.

Kocken P, Van Dorst A, Schaalma H. The relevance of cultural factors in predicting condom-use intentions among immigrants from the Netherlands Antilles. Health Educ Res. 2005;21(2):230–8.

Moore SG, Dahl DW, Gorn GJ, Weinberg CB. Coping with condom embarrassment. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(1):70–9.

Moore SG, Dahl DW, Gorn GJ, Weinberg CB, Park J, Jiang Y. Condom embarrassment: coping and consequences for condom use in three countries. AIDS Care. 2008;20(5):553–9.

DeMaria AL, Ramos-Ortiz J, Faria AA, Wise GM. Examining consumer purchase behaviors and attitudes toward condom and pharmacy vending machines in Italy: a qualitative study. J Consum Affairs. 2020;54(1):286–310.

Wong M, Chan RK, Tan H, Sen P, Chio M, Koh D. Gender differences in partner influences and barriers to condom use among heterosexual adolescents attending a public sexually transmitted infection clinic in Singapore. J Pediatr. 2013;162(3):574–80.

Yeo TED, Ng YL. Sexual risk behaviors among apps-using young men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2016;28(3):314–8.

Abdullah A, Fielding R, Hedley A, Ebrahim S, Luk Y. Reasons for not using condoms among the Hong Kong Chinese population: implications for HIV and STD prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(3):180–4.

Reeves B, Ickes MJ, Mark KP. Gender differences and condom-associated embarrassment in the acquisition of purchased versus free condoms among college students. Am J Sex Educ. 2016;11(1):61–75.

Brackett KP. College students’ condom purchase strategies. Soc Sci J. 2004;41(3):459–64.

Liu T, Fuller J, Hutton A, Grant J. Consequence-based communication about adolescent romantic experience between parents and adolescents: a qualitative study underpinned by social constructionism. Nurs Health Sci. 2017;19(2):176–82.

Hubach RD, Dodge B, Goncalves G, Malebranche D, Reece M, Van Der Pol B, Martinez O, Schnarrs PW, Nix R, Fortenberry JD. Gender matters: condom use and nonuse among behaviorally bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(4):707–17.

Whitton SW, Newcomb ME, Messinger AM, Byck G, Mustanski B. A longitudinal study of IPV victimization among sexual minority youth. J Interpers Violence. 2019;34(5):912–45.

Choi EP, Wong JY, Fong DY. An emerging risk factor of sexual abuse: the use of smartphone dating applications. Sex Abuse. 2018;30(4):343–66.

Stephenson R, Freeland R, Finneran C. Intimate partner violence and condom negotiation efficacy among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. Sex Health. 2016;13(4):366–72.

Lyons HA, Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. Young adult casual sexual behavior: life-course-specific motivations and consequences. Sociol Perspect. 2014;57(1):79–101.

Funding

The project was supported by Seed Fund for Basic Research, the University of Hong Kong (Reference: 201611159180).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EPHC: data analysis, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript; DYTF: design of the work, acquisition of data, interpretation of data and revising the manuscript; JYHW: design of the work, acquisition of data, interpretation of data and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB). Reference: (UW16-394).Written informed consent was obtained for each participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

The figure shows the factor structure of the revsied UCLA MCAS.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, E.P.H., Fong, D.Y.T. & Wong, J.Y.H. The use of the Multidimensional Condom Attitude Scale in Chinese young adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 331 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01577-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01577-9