Abstract

Background

The literature regarding the effect of health literacy on college students’ psychological health and quality of life is scarce. The purpose of conducting this cross-sectional study was to examine the effect of health literacy on certain psychological disturbances (perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity) and quality of life of college students.

Methods

A cross-sectional quantitative design was utilized in this study. A total of 310 four-year college students participated in this study. The students completed a demographics questionnaire as well as already established and validated measures of health literacy, perceived stress, depressive symptoms, impulsivity, and quality of life. Structural equation modeling was performed to analyze the data to explore the effect of health literacy on the psychological disturbances and quality of life.

Results

The results showed that health literacy has a negative effect on three psychological disturbances commonly experienced by college students; perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity. In addition, the effect of health literacy on the quality of life was positive.

Conclusion

The proposed conceptual model was supported. College students’ counseling staff could use the findings to better address students’ needs pertinent to psychological health and quality of life. Future research is warranted to develop a more comprehensive model that explains the role of health literacy in determining college students’ psychological health and quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health literacy is a concept that describes the ability to acquire, understand, process, and utilize health-related information [1,2,3]. Individuals could be classified as having adequate/good or limited/poor health literacy levels. Being health literate enables the person to make informed decisions regarding his/her own health or the health of others, family members for example [1, 3, 4]. Conversely, limited health literacy negatively affects the overall health status of individuals and communities [5]. Despite its importance in determining the overall health and well-being, health literacy remains an area of inquiry that is often neglected in research [3]. One of the main existing issues is that most health literacy research studies have been conducted in the U.S., Europe, and Australia. Another concern is the focus on measuring functional health literacy and the reading abilities [1, 3]. Moreover, Nutbeam and colleagues maintained that the multidimensional nature of health literacy makes it a challenging concept to define and measure [2].

The relationship between health literacy and overall health has recently gained more attention in research, and limited health literacy is reportedly a key determinant of health and well-being. Health promotion and disease prevention are negatively affected by limited health literacy [3, 6]. In addition, limited health literacy affects a variety of health aspects including management of chronic health conditions, making decisions regarding healthy habits, misunderstanding of and poor compliance with prescribed medications, more frequent hospital admissions, and mortality [3, 5]. Moreover, utilization of expensive healthcare services including specialized and emergency services increases with limited health literacy [7, 8]. Such detrimental effects increase the burden on healthcare systems and inflate costs [7, 9].

Regarding the health literacy of college students, a review of the literature showed that research of this area is still evolving. A focus point of investigation has been the measurement of the level of health literacy among college students. Sansom-Daly and colleague conducted a systematic review and found that at least 60% of adolescents and young adults, including college students, have adequate health literacy [10]. Other research studies reported lower levels of health literacy [11, 12]. In addition, disparities of health literacy in college students exist related to age, gender, and field of study [13, 14]. In terms of its relationship with college students’ health, lower health literacy was associated with such health indicators of physical health as obesity and smoking [10]. However, evidence regarding the association between health literacy and other health domains including psychological disturbances and quality of life (QOL) is limited. The following discussion will summarize the literature regarding college students’ psychological disturbances and QOL.

Psychological disturbances among college students

College students experience a variety of psychological disturbances throughout their study journey. Compared to their pre-enrollment status, college students reported worsening of psychological well-being during their course of study [15]. The level of distress experienced by college students is higher than the level reported by the general population [15, 16]. Perceived stress positively correlates with psychological distress and is frequently reported as a main psychological disturbance experienced by college students [17]. Previous studies showed that perceived stress negatively impacts academic performance as well as physical and psychological health [18, 19].

Another major concern regarding college students’ psychological health is depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms affect college students around the globe [20, 21]. The prevalence of depressive symptoms is reportedly higher in college students than in the general population [22]. Depressive symptoms are not only associated with poor academic performance [23], but also convey detrimental effects on college students’ health including an increased risk of alcohol use [24], unhealthy eating [25], and sleep disturbances [26]. Moreover, there is evidence that suicidal ideation is a consequence of even mild to moderate levels of depressive symptoms among college students [27].

College students respond to psychological distress in diverse ways. Impulsivity, defined as “a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these reactions to the impulsive individual or to others” [28], is considered a key determinant of an individual’s behaviors and reaction to distress. In general, impulsivity affects nearly all aspects of daily life [29]. Many research studies have been conducted to better understand the relationship between impulsivity and unhealthy behaviors. According to the literature, impulsivity is associated with increased risk of problematic drinking and unhealthy eating [30, 31]. Chamorro and colleagues maintained that the impact of impulsivity on health behaviors is usually more apparent among younger populations, e.g. college students [32]. In addition, impulsivity interacts with psychiatric problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD) and suicidal ideation and attempts [33, 34].

QOL among college students

While there is no consensus on the definition of QOL, many resources agree that it involves an individual’s satisfaction with health and life [35, 36]. Physical and human resources as well as student services affect college students’ QOL [37]. Healthy populations, like most college students, have better QOL compared to patients with chronic diseases [38]. However, the literature shows that both psychological and physical health can impact college students’ QOL [39]. In turn, QOL is correlated with academic achievement and health promotion of college students [37]. However, the existing literature regarding health literacy effect on college students’ QOL is still not well-understood [36]. Thus, this study was conducted to examine the effect of health literacy on certain psychological disturbances (perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity) and quality of life of college students.

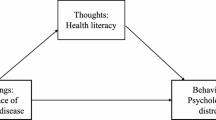

Based on the previous discussion, college students are at high risk for different psychological disturbances including depressive symptoms, stress, and impulsivity. Such disturbances could mitigate college students’ QOL. As presented earlier, the health literacy of many college students is limited. However, the effect of health literacy on college students’ psychological health and QOL is still not well-understood. Therefore, this study was conducted to better understand how health literacy affects certain psychological disturbances experienced by college students and their QOL. The current study was guided by a conceptual model that has been developed based on the extensive review of the literature.

Health literacy is hypothesized in this model as the latent exogenous construct. Health literacy was determined using the nine scales of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ) [40]. Psychological status and QOL were proposed as the latent endogenous variables. Three psychological disturbances (perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity) were purported as key determinants of college students’ psychological status. QOL was determined using the four domains of health and functioning, social and economic, psychological/spiritual, and family [35]. Two research hypotheses were formulated to test the model proposed in this study:

Hypothesis #1: the greater college students’ health literacy, the less psychological disturbances.

Hypothesis #2: college students’ health literacy positively affects their QOL.

Methods

Design and setting

This study was conducted using a cross-sectional quantitative design. It was carried out at a large, public university in north Jordan.

Sampling and participants

Proportional quota sampling method was used to conduct the current study. This sampling method was employed to recruit participants representative of both the different fields of study and the year of study. Undergraduate college students were invited to participate in the study. A total of 310 undergraduate students completed the data collection questionnaires. The average age of study participants was 20.89 years old (SD = 2.0). Male students represented 52.9% of participants. The average BMI was 24.3 kg/m2 (SD = 4.45) with a range from 16.22 to 44.4 kg/m2. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the participants.

Data collection

The participants were invited to complete paper-based questionnaires including a demographics questionnaire, HLQ, Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R), Barret Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) (BIS-11), and the generic version of the Quality of Life Index (QLI). College students’ height and weight were obtained by one trained research assistant using the same scale to enhance reliability of measurements. Using the obtained height and weight, the BMI was calculated as the college student’s weight (in Kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters).

Health literacy

The HLQ is composed of 44 items classified under nine distinct scales, identified earlier, representing the health challenges and needs of people [40]. The nine scales of the HLQ are: a) “Feeling understood and supported by healthcare providers”, b) “Having sufficient information to manage my health”, c) “Actively managing my health”, d) “Social support for health”, e) “Appraisal of health information”, f) “Ability to actively engage with healthcare providers”, g) “Navigating the healthcare system”, h) “Ability to find good health information”, and i) “Understand health information”. The first five scales contain items with responses ranging from one (strongly disagree) to four (strongly agree). On the other hand, the scales six through nine include items with five response ranging from one (cannot do or always difficult) to five (always easy). It is recommended to obtain the scores of the nine scales instead of calculating a total score of the HLQ [40]. To obtain the scores of the nine scales, the average of the items is obtained. Possible total scores range from one to four in the first five scales and one to five in the scales six through nine. Higher scores of the HLQ scales indicate better levels of health literacy. Internal consistency of the nine scales of the HLQ was supported in the current study with Cronbach’s α values ranging from .71 to .83.

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured using the PSS-10; a 10-item, easy to understand tool [41]. The participants were asked to report their own appraisal regarding how much specific situations have been stressful during the last month. The PSS-10 employs a five-point Likert scale ranging from zero (never) to four (very often). Positive items were reversed before running analyses and then the total score was obtained by summing up the scores of individual items. The higher the total score on the PSS-10, the greater the perceived stress is. The Cronbach’s α value for the PSS-10 in this study was .73.

Depressive symptoms

The CESD-R was used to screen for depressive symptoms among the participants [42]. The CESD-R is a 20-item instrument that includes questions about the nine groups of depressive symptomatology as described by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V). Each item is self-reported on a scale from zero (not at all or less than 1 day) to four (nearly every day for 2 weeks). The total score is calculated as the sum scores of individual items of the CESD-R. The higher the CESD-R score, the more severe depressive symptoms are. The Cronbach’s α value for the CESD-R in this study was .93.

Impulsivity

The BIS-11 was used to measure participants’ impulsivity. The BIS-11 is a 30-item scale that could be self-rated on a four-point scale ranging from one (rarely/never) to four (almost always/always) [43]. The scale is composed of six, first order factors: attention, cognitive instability, motor, perseverance, self-control, and cognitive complexity. After reversing the negatively worded items, the total impulsivity score is calculated by summing up the item scores. According to Patton and colleagues, higher scores indicate higher level of impulsivity. The Cronbach’s α value for the BIS-11 in this study was .66.

QOL

The generic version of the QLI was administered to measure participants’ QOL [35]. Besides measuring the overall QOL, the QLI provides information regarding the QOL in the following domains: a) health and functioning, b) social and economic, c) psychological/spiritual, and d) family. The QLI involves two sections with a total of 66 items: the first section is used to assess satisfaction with 33 items, and the second assesses the importance of those 33 items to the individual. A six-point scale is used in the QLI, with a score of one means “very dissatisfied” and “very unimportant” and a score of six means “very satisfied” and “very important”. The total QLI score ranges from zero to 30 following a syntax provided by the instrument developers, with a higher score indicating better QOL. The Cronbach’s α value for the QLI in this study was .91.

Data analysis

In this study, SPSS (Version 23) and AMOS (Version 23) were used to perform the analyses. SPSS was used to perform descriptive analysis and estimate the internal consistency of the instruments. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed using AMOS. SEM, with Maximum Likelihood Estimation, was conducted and the process involved two main phases. In the first phase, a pooled Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was done to assess the appropriateness of the proposed measurement model prior to going forward into the second phase. The main purpose of performing CFA was to assess the validity and other parameters regarding the factor structure of the measurement model. In the pooled CFA, all latent constructs were entered into the analysis and tested simultaneously. The specific parameters and criteria used to assess the measurement model appropriateness are discussed in the results section. It is worth noting that the pooled CFA method was used for two reasons: a) it is more useful to assess the whole measurement model instead of examining the factor structure of individual constructs (e.g. health literacy), and b) presenting the results regarding the CFA for each construct is beyond the limit of a single research article.

In the second phase, the structural model (i.e. SEM model causal pathways) was tested. Initially, the direct effect of health literacy on the psychological disturbances (hypothesis 1) and QOL (hypothesis 2) was examined. In this study, the results were not interpreted solely based on the Chi Square statistic because it is sensitive to large sample size [44]. According to Hair and colleagues, model fitness is better assessed using at least one fit index from three categories of model fitness (i.e. absolute fit, incremental fit, and parsimonious fit) [44]. Thus, the following indices were set a priori and used in the analyses presentation and interpretation: a) absolute fit: Root Mean Square of Error Approximation (RMSEA) < .07, b) incremental fit: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > .92, and c) parsimonious fit: Chi Square/Degrees of Freedom (Chisq/df) < 5. RMSEA and CFI values were set at these levels considering the number of observed variables in the conceptual model and the sample size [44]. Standardized regression weights (β) were also assessed and interpreted during the second phase of analysis.

Results

Preliminary analysis: measurement model using pooled CFA

The factor structure of the measurement model was assessed first. Discriminant validity was initially evaluated based on the correlations among the constructs of the proposed model. “Low correlations” are indicative of discriminant validity [44]. The results showed that the correlations were all moderate (ranging from −.46 to −.63); which could be a threat to the discriminant validity. To further assess the discriminant validity, the values of the squared root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct were calculated and compared to the inter-construct correlations. Discriminant validity is supported when the squared root AVE of a construct is greater than the inter-construct correlation with any other construct in the model [44]. The results (see Table 2) supported the discriminant validity with values of squared root AVE exceeding the inter-construct correlations, except for the construct psychological disturbances. On the other hand, convergent validity of the individual constructs was evaluated based on the AVE of ≥ .5 [44]. Then composite reliability (CR) of the individual constructs were calculated to assess factor reliability. All CR values of the constructs, except the construct “psychological disturbances, were above the cutoff point of .7 suggested by Hair et al.; indicating that convergent validity or internal consistency is supported. In Table 2, inter-construct correlations are summarized along with the AVE and CR for each construct.

Regarding the fit indices, the measurement model showed less than acceptable fit with RMSEA = .09, CFI = .904, and Chisq/df = 3.58. An investigation of the modification indices revealed that the fit of the measurement model could be improved through freeing some within-factor paths (namely e3-e5, e2-e5, e1-e8, and e1-e3). The model fitness indices have improved after adding covariances between these paths; RMSEA = .076, CFI = .936, and Chisq/df = 2.79 (See Fig. 1). Based on the results of the measurement model fit as well as its reliability and validity, we moved forward with conducting the SEM. Figure 1 shows the measurement model and the results pertinent to its reliability and validity including the standardized factor loadings and R2.

Summary of Measurement Model Fitness, Reliability, and Validity. HL: Health Literacy, HPS: Feeling understood and supported by healthcare providers, HIS: Having sufficient information to manage my health, AMH: Actively managing my health, SS: Social support for health, CA: Appraisal of health information, AE: Ability to actively engage with healthcare providers, NHS: Navigating the healthcare system, FHI: Ability to find good health information, UHI: Understand health information, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale-10, CESD-R: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised, BIS: Barret Impulsiveness Scale-11, QOL: Quality of Life, HF: Health and Functioning, Soc: Social and Economic, PsyS: Psychological/Spiritual, Fam: Family.

Hypotheses testing

The SEM analysis revealed the following fit indices: RMSEA = .074, CFI = .94, Chisq/df = 2.71 (df = 96). These fit indices, except for the RMSEA, meet the criteria set a priori. The model is depicted with a summary of model fit indices and the other parameters (see Fig. 2).

SEM Model. HL: Health Literacy, HPS: Feeling understood and supported by healthcare providers, HIS: Having sufficient information to manage my health, AMH: Actively managing my health, SS: Social support for health, CA: Appraisal of health information, AE: Ability to actively engage with healthcare providers, NHS: Navigating the healthcare system, FHI: Ability to find good health information, UHI: Understand health information, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale-10, CESD-R: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised, BIS: Barret Impulsiveness Scale-11, QOL: Quality of Life, HF: Health and Functioning, Soc: Social and Economic, PsyS: Psychological/Spiritual, Fam: Family.

Hypothesis #1

Regarding Hypothesis #1, the R2 value of the psychological disturbances construct was .21; meaning that health literacy explains 21% of the predicted variance. The standardized regression weight value regarding the effect of health literacy on the psychological disturbances construct was statistically significant (β = −.46, p < .001). This means that one standard deviation increase in health literacy produces a .46 standard deviation reduction in the psychological disturbances (Table 3).

Hypothesis #2

On the other hand, the R2 value of the QOL construct was .52; indicating that health literacy explains 52% of the predicted variance. The β value regarding the effect of health literacy on QOL was also statistically significant (β = .37, p < .001). In other words, an increase of one standard deviation in the health literacy construct results in .37 standard deviation increase in the QOL construct. These results (see Table 3) indicate that both hypotheses were supported; the greater college students’ health literacy, the less psychological disturbances and the better QOL.

Discussion

Health literacy plays a key role in determining the overall health status of individuals and communities. Research on health literacy is still evolving and the effect of health literacy on college students’ psychological health and QOL is not thoroughly understood. Therefore, the authors intended to investigate the role of health literacy on these domains of health in this study. A model was proposed, and two distinct hypotheses were tested using SEM analyses. The measurement model was assessed, and the results indicated that its factor structure is adequate. The structural model was then assessed, and the results indicated that the model fitness indices are supported. Results regarding the structural model indicated that the proposed hypotheses were supported. Health literacy had both a statistically significant negative effect on the psychological disturbances under investigation and a statistically significant positive effect on college students’ QOL.

Perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity are among the many psychological disturbances often experienced by college students. The literature shows that such disturbances negatively affect college students’ overall health and academic performance [29, 33]. In addition, psychological disturbances negatively influence health literacy and help-seeking behaviors of college students [45]. However, the opposite effect of health literacy on psychological disturbances, has not been studied yet, to the best of the authors’ knowledge. Thus, the current study adds to the existing knowledge that health literacy could decrease the risk of common psychological problems. In other words, improving college students’ health literacy could lead to better outcomes evidenced by a reduction in the perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity.

Regarding the effect of health literacy on college students’ QOL, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that health literacy has a mild correlation with college students’ QOL [36]. Further investigation of this area was recommended by Zheng and colleagues [36]. Support of the second hypothesis in this study is consistent with the findings of that systematic review. The current study did not include an investigation of the relationship between health literacy, QOL, and academic performance. However, previous research showed that improving college students’ QOL could play an essential role in achieving better academic and health-promoting outcomes [37]. Hence, the results of the current study open the door for further investigation regarding the improvement of college students’ academic performance through enhancement of health literacy and QOL.

Implications

The results of this study could be useful for college staff involved with counseling services provided to college students. Schwitzer and colleagues reported that seeking counseling services is associated with positive improvement of academic performance [46]. It was, also, concluded in a systematic review that expanding the expertise of those involved with college students’ counseling has a crucial impact on supporting college students [47]. Thus, understanding how health literacy affects psychological well-being and QOL could be useful for university counseling staff. Offering training for counseling personnel regarding health literacy and its effects on college students’ psychological disturbances and QOL is paramount. It should be emphasized that providing valid information to college students could improve their psychological well-being and QOL. In addition, the results of this study could be useful for college students to increase their awareness regarding how health literacy affects their psychological health and QOL.

Healthcare workers interested in college students’ health and health promotion could also benefit from the results of this study. Health literacy, as mentioned earlier, enables individuals to make appropriate, informed decisions regarding their own health and the health of others. Enabling individuals to make such decisions lies at the core of providing patient-centered care; a fundamental element of providing quality health care. Thus, understanding how health literacy affects psychological well-being and QOL needs to be acknowledged by healthcare professionals involved with promoting college students’ health. Healthcare providers are encouraged to meet college students’ needs through designing and implementing health promotion programs that emphasize the key role of informing and enabling individual college students. In turn, this could carry a positive effect on adopting a healthy lifestyle that could minimize the risk for chronic health problems.

Recommendations for future research

The current study provides a preliminary model about the effect of health literacy on the psychological disturbances and QOL of college students. Future research, both exploratory and interventional, is needed to better understand this area of research. Further research that integrates other indicators of psychological stress, such as anxiety, is warranted. Incorporating other domains of health, such as physical health and health promotion, seems necessary to provide more insights regarding the potential effect of health literacy on college students’ overall health. We employed a SEM analysis and examined the impact of health literacy on the psychological disturbances and QOL of college students. However, there is a need to expand the model and integrate potential mediators and/or moderators that should also be investigated. Examples include college students’ age, gender, and field of study. For example, the literature suggests that college students’ gender is considered as a source of disparity of health literacy [13, 14]. Conducting multisite research with college students from different cultural and sociodemographic backgrounds should also be considered.

Limitations

The results of the current study should be interpreted within the context of the study limitations. This study was conducted at one setting; consequently, the generalizability of the findings might be limited. A cross-sectional data collection approach was used in the current study. Conducting a longitudinal research with data collection at different time points, for example at the end of each academic year, would add more rigor. Regarding sampling, a proportional quota sampling method was used. However, the descriptive statistics showed that we had more college students from the health-related faculties, like medicine and nursing. The literature shows that the number of health education topics studied is positively correlated with college students’ health literacy [12].

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that health literacy mitigates certain psychological disturbances; perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity. In addition, it has a positive effect on improving college students’ QOL. These results add insights to the existing literature and provide ideas regarding conducting future research. The conceptual model was supported by the results; however, other domains of health should be added and tested. Expanding the model could play a key role in strengthening health promotion programs designed for college students.

Availability of data and materials

Per the regulations of the host university, sharing the datasets used and analyzed in the current study is not permissible.

References

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, Holland A, Brasure M, Lohr KN, Harden E, Tant E. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;199(1):941.

Nutbeam D, McGill B, Premkumar P. Improving health literacy in community populations: a review of progress. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(5):901–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax015.

World Health Organization. Health literacy. The solid facts. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/190655/e96854.pdf (2013). Accessed 1 Dec 2019.

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, Brand H. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington, DC: Author. Adolescent health, World Health Organization (WHO); 2010. p. 33–4.

Jayasinghe UW, Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, van Driel M, Mazza D, Del Mar C, Lloyd J, Smith J, Zwar N, Taylor R. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0471-1.

Rasu RS, Bawa WA, Suminski R, Snella K, Warady B. Health literacy impact on national healthcare utilization and expenditure. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(11):747. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.151.

Vandenbosch J, Van den Broucke S, Vancorenland S, Avalosse H, Verniest R, Callens M. Health literacy and the use of healthcare services in Belgium. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016 Oct 1;70(10):1032–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206910.

Haun JN, Patel NR, French DD, Campbell RR, Bradham DD, Lapcevic WA. Association between health literacy and medical care costs in an integrated healthcare system: a regional populationbased study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):249. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0887-z.

Sansom-Daly UM, Lin M, Robertson EG, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Girgis A, Cohn RJ. Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: an updated review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016;5(2):106–18. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2015.0059.

Ramezankhani A, Ghafari M, Rakhshani F, Ghanbari S, Azimi S. Comparison of health literacy between medical and non-medical students in Shahid Beheshti universities in the academic year 92-93. Pajoohandeh J. 2015 Jun 15;20(2):78–85.

Sukys S, Cesnaitiene VJ, Ossowsky ZM. Is health education at university associated with students’ health literacy? Evidence from cross-sectional study applying HLS-EU-Q. Biomed Res Int. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8516843.

Rababah JA, Al-Hammouri MM, Drew BL, Aldalaykeh M. Health literacy: exploring disparities among college students. BMC Public Health. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):1401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7781-2.

Vamos S, Yeung P, Bruckermann T, Moselen EF, Dixon R, Osborne RH, Chapa O, Stringer D. Exploring health literacy profiles of Texas university students. Health Behav Pol Rev. 2016;3(3):209–25. https://doi.org/10.14485/HBPR.3.3.3.

Bewick B, Koutsopoulou G, Miles J, Slaa E, Barkham M. Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Stud High Educ. 2010;35(6):633–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643.

Deasy C, Coughlan B, Pironom J, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: A mixed method enquiry. Plos One. 2014;9(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115193.

Saleh D, Camart N, Romo L. Predictors of stress in college students. Front Psychol. 2017;8:19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00019.

Thomas JJ, Borrayo EA. The impact of perceived stress and psychosocial factors on missed class and work in college students. J Coll Couns. 2016 Oct;19(3):246–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12047.

Rosiek A, Rosiek-Kryszewska A, Leksowski Ł, Leksowski K. Chronic stress and suicidal thinking among medical students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13020212.

Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054.

Schofield MJ, O'Halloran P, McLean SA, Forrester-Knauss C, Paxton SJ. Depressive symptoms among a ustralian university students: who is at risk? Aust Psychol. 2016;51(2):135–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12129.

Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatry Res. 2013;47(3):391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015.

Carton ST, Goodboy AK. College students’ psychological well-being and interaction involvement in class. Commun Res Rep. 2015;32(2):180–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2015.1016145.

Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(4):595. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025807.

Ward RM, Hay MC. Depression, coping, hassles, and body dissatisfaction: factors associated with disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2015;17:14–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.002.

Becker SP, Jarrett MA, Luebbe AM, Garner AA, Burns GL, Kofler MJ. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health. 2018;4(2):174–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.001.

Cukrowicz KC, Schlegel EF, Smith PN, Jacobs MP, Van Orden KA, Paukert AL, Pettit JW, Joiner TE. Suicide ideation among college students evidencing subclinical depression. J Am Coll Heal. 2011;59(7):575–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.483710.

Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1783–93. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783.

Piko BF, Pinczés T. Impulsivity, depression and aggression among adolescents. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;69:33–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.008.

Caswell AJ, Celio MA, Morgan MJ, Duka T. Impulsivity as a multifaceted construct related to excessive drinking among UK students. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv070.

Jasinska AJ, Yasuda M, Burant CF, Gregor N, Khatri S, Sweet M, Falk EB. Impulsivity and inhibitory control deficits are associated with unhealthy eating in young adults. Appetite. 2012;59(3):738–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.001.

Chamorro J, Bernardi S, Potenza MN, Grant JE, Marsh R, Wang S, Blanco C. Impulsivity in the general population: a national study. J Psychiatry Res. 2012;46(8):994–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.023.

Roley ME, Contractor AA, Weiss NH, Armour C, Elhai JD. Impulsivity facets’ predictive relations with DSM–5 PTSD symptom clusters. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000146.

Wang L, He CZ, Yu YM, Qiu XH, Yang XX, Qiao ZX, Sui H, Zhu XZ, Yang YJ. Associations between impulsivity, aggression, and suicide in Chinese college students. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):551. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-551.

Ferrans C, Powers M. Quality of life index: development and psychometric properties. Adv Nurs Sci. 1985;8:15–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198510000-00005.

Zheng M, Jin H, Shi N, Duan C, Wang D, Yu X, Li X. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16(1):1–0. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1031-7.

Demirdağ S. Determining the quality of life of students in higher education. J Higher Educ Sci. 2018;8(1):051–61.

Suleiman IA, Henry MT, Eneyi KE. Quality of life of healthy subjects and patients with arthritis and diabetes mellitus in Bayelsa state, Niger Delta region. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16(7):1729–35. https://doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v16i7.34.

Vaez M, Laflamme L. Health behaviors, self-rated health, and quality of life: a study among first-year Swedish university students. J Am Coll Heal. 2003;51(4):156–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480309596344.

Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, Hawkins M, Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):658. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-658.

Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. p. 31–67.

Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. p. 363–77.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::AID-JCLP2270510607>3.0.CO;2-1.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. Pearson; 2010.

Kim JE, Saw A, Zane N. The influence of psychological symptoms on mental health literacy of college students. Am J Orthop. 2015;85(6):620. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000074.

Schwitzer AM, Moss CB, Pribesh SL, John DJ, Burnett DD, Thompson LH, Foss JJ. Students with mental health needs: college counseling experiences and academic success. J Coll Stud Dev. 2018;59(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0001.

Storrie K, Ahern K, Tuckett A. A systematic review: students with mental health problems—a growing problem. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01813.x.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was fully supported by the Deanship of Research at Jordan University of Science and Technology (Award number 82/2018). The Deanship of Research fully supported printing the paper-based questionnaires and provided the financial support to buy SPSS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR: conception of the research idea, building the overall study design, and supervising the data collection. He performed the data analysis and prepared this manuscript. MA: contributed to the conception of the main idea, made substantial contribution toward preparing the data collection tools, and assisted with the data analysis. He also revised and approved this manuscript. BD: substantially contributed to building the development of the research idea and the overall study design. She also revised and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Jordan University of Science and Technology before recruiting the first participant. An informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to collecting data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rababah, J.A., Al-Hammouri, M.M. & Drew, B.L. The impact of health literacy on college students’ psychological disturbances and quality of life: a structural equation modeling analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 292 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01541-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01541-7