Abstract

Background

An increasing number of international organisations and national governments have committed to well-being promotion. Unfortunately, important questions regarding how to assess well-being are still unresolved, making policy implementation and evaluation difficult.

Methods

This research expanded on Huppert and So’s (Soc Indic Res. 110, 837–861 2013) multidimensional subjective well-being framework by investigating the replicability of the model in two non-European regions (South America, represented by Brazil and Colombia, and Eastern Africa, represented by Uganda), and the United Kingdom. Additionally, previous limitations of the framework were also addressed.

ESS Round Six items were crucially improved in terms of temporal and response scale consistency. Bayesian approximate measurement invariance was applied on a sample of 381 young adult participants to test for consistency across countries.

Results

The Huppert & So (Soc Indic Res. 110, 837–861 2013) model was found to fairly replicate across non-European regions, where meaningful differences in well-being patterns across regions were observed. Additionally, estimated well-being was related with other well-being measures (Five Ways): Learn and Connect were the strongest predictors of general well-being, with Take Notice and Give being associated with specific aspects of it.

Conclusions

Based on this narrow sample of young adults, it appears the ten-item measure proposed by Huppert & So (Soc Indic Res. 110, 837–861 2013) is useful for assessing population mental health outside of Europe. This is only an initial attempt to assess qualities, so further testing should be done before applying at scale for identifying policy opportunities to address well-being of populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is an increasing prevalence in arguments highlighting the limitations of traditional economic measurements as indicators of population well-being [1]. Major supranational organisations, including the OECD, WHO and UN, have acknowledged the need for the direct measurement of well-being due to such evidence-based assertions. Significantly, for the first time the promotion of well-being has been recognised as part of the global development agenda in the United Nation’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals outlined in 2016. Progress towards the direct measurement of well-being has concurrently been made on a national-level, with more than 40 countries reportedly measuring citizens’ well-being [1]. For example, there have been initiatives in the United Kingdom assessing the impact of specific policies on well-being since 2010. Nevertheless, although there have been a number of attempts to develop a cross-culturally validated well-being measurement tool for international use and comparisons, such attempts have had limited success (e.g. [2, 3]).

Determining the standards by which to measure or define “well-being” has proven to be a persistent challenge. However, one increasingly common framework distinguishes between hedonic well-being, which corresponds to “positive feeling”, and eudaimonic well-being, which corresponds to “positive functioning” [4]. A number of multidimensional scales integrating these two components have been developed, such as the “Satisfaction with Life Scale” [5], Lyubomirsky and Lepper’s “Subjective Happiness Scale” [6], the “Flourishing Scale” [7], the PANAS scale [8], and the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire [9]. Such multidimensional approaches to the measurement of well-being are increasingly favoured because they offer a more holistic assessments of an individual’s experience, as well as a robust framework upon which improvements can be made. Cross-cultural validation is a particularly important consideration since the integrity of international comparisons will rely on the premise that the same construct is being adequately captured across diverse populations [5, 10].

This paper seeks to build on previous work conducted on multidimensional well-being assessments. Specifically, the well-being module developed for the European Social Survey [11] represents a unique undertaking because of the scope of its sample (more than 43,000 Europeans), the cross-cultural validity of the model derived (including representative samples of 23 countries), and the anticipated applications of their findings to policy. Within this framework, 19 items were later identified by Huppert and So [4] as markers of ten crucial well-being dimensions. These dimensions were derived as opposites of the diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Episode, Depressive Episode, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) of the International Classification of the American Psychiatric Association (1994) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) of the World Health Organization (1993). From their analyses of the ESS data, Huppert and So [4] developed a two-factor model to account for their ten proposed dimensions of well-being. The first factor, which they termed “Positive Characteristics” (PC) included: emotional stability, vitality, resilience, optimism, positive emotion and self-esteem. The second, which they termed “Positive Functioning” (PF) included: engagement, meaning, positive relationships and competence.

Unfortunately, the Huppert and So [4] approach presented relevant limitations, as some items referred to different time windows and made use of different response scales (p.843, [4]). Additionally, this framework was only assessed using European samples, hindering its generalisability to alternative populations. In our application, we aim to amend both issues: whereas questions from the ESS survey use a range of words to indicate time-period, from specific phrases such as ‘in the past week’ to more general ones such as ‘often’, this questionnaire prompted participants to answer with reference to ‘in general’ for every question. Additionally, all items were presented using a common response scale. We tested this improved questionnaire in countries across different geographical regions (following United Nation’s regions) outside the ESS application region: Brazil, Colombia (South America) and Uganda (Easter Africa). Accordingly, the primary purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility of the measures in new settings, not to conclude the overall fit of items or a final recommendation for application at scale. Lastly, original scale characteristics (i.e., the presence of two well-being factors) were retained in this study so the results obtained with the improved scale were directly comparable with those of the original publication.

We further assessed the criterion validity of the new scale version by investigating how the dimensions proposed by Huppert and So’s model [4] were linked to alternative well-being behavioural markers. Among those, the Five Ways to Wellbeing (Five Ways, namely Connect, Be Active, Take Notice, Give and Learn; Government Office for Science, 2008), reflect some specific behaviours associated with improved well-being [12, 13]. Accordingly, this article will evaluate how each of the Five Ways impacted the different well-being components across the explored regions.

Methods

Participants

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Department of Psychology Ethics Committee (PEC), University of Cambridge. Consent was obtained from all participants, and a debrief was presented upon completion of the study. Recruitment was conducted over a period of 3 weeks between March and April 2017 in Brazil, Uganda, Colombia, and the United Kingdom with the support from local non-governmental organizations and academics. Qualtrics was used to recruit participants from Colombia due to difficulties in collecting complete questionnaires through other methods. While a larger sample had been targeted for a full-scale validation, the aim of this study is to provide initial evidence of the psychometric properties of an improved scale in alternative contexts outside European regions.

Importantly, the diverse geographical regions under investigation were selected to represent areas not previously tested within the context of the ESS. The geographic area selection intentionally aimed to avoid introducing systematic bias of presenting highly similar countries belonging to similar cultural, geographical and economic backgrounds. We additionally control for age differences by only including participants who were aged 18 to 24 years. Lastly, even though respondents were requested to have some proficiency in English (to respond to opening demographic questions), well-being and the Five Ways items were translated to local languages.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform, and participants were granted access to the questionnaire through an emailed link. The self-report questionnaire (Appendix A) consisted of sociodemographic questions, ten items assessing different ‘dimensions’ of well-being [4, 11] and the Five Ways items as follows:

Firstly, sociodemographic measures for age, gender, primary nationality, years of education, and employment status were included at the start of the questionnaire and were written in English. Following the initial sociodemographic questions, participants were asked to select their native language before accessing the main questionnaire. The main questionnaire contained the ten well-being dimension’s items plus the Five Ways questions. The well-being dimension items were those designed for ESS Round Three [11] and later selected by Huppert and So [4] to develop their well-being model. It is noteworthy that these items were additionally found in ESS Round Six (2012), where they presented minor changes in the former due to floor effects observed in Round Three. Additionally, the Five Ways to Wellbeing [14] were measured using the items also included in the ESS Round Six well-being module. Accordingly, the original questions that we aimed to improve were those of the ESS Round Six well-being model.

Two major changes were conducted: firstly, all items were placed on the same seven-point Likert scale to ensure better internal consistency and to ameliorate the negatively skewed responses that were found in the ESS Round Three and Six. Secondly, all items were adjusted to achieve temporal consistency across items such that all questions were answered with reference to the prompt “in general” instead of referring to specific time periods (e.g. in the last week, in the last year). We further modified the wording of the resilience item to ensure the same directionality of all questions. The specific questions associated with each of these items are displayed in Table 1.

Huppert and So’s [4] and the Five Ways questionnaire items were translated from English to Spanish, and Portuguese, following World Health Organization (WHO) translation guidelines (Appendix B).

Statistical analyses

Bayesian Structural Equation Modelling (BSEM) was used to study whether: a) evidence supported previous findings regarding multidimensional well-being (whether the dimensions and well-being factors were found); b) to assess meaningful cross-country differences. To this end, we employed approximate measurement invariance. BSEM represents a critical improvement over traditional SEM and CFA models, where cross-loadings and residual correlations are not fixed to zero, but given “informative, small-variance priors” ([15], p.316). This flexibility represents a substantive improvement in terms of model fit and parameter estimation, and its use has been widely adopted in cross-cultural survey analysis (see references in Appendix C). Following the guidelines described in [16,17,18,19], a nested-model approach was followed for estimating the BSEM models. Additionally, a comparison of BSEM with traditional estimation frameworks (confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis) was performed. A detailed report of the analyses can be found in Appendix C.

All models were estimated in Mplus 7 [20, 21]. Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis (BCFA) models were sampled in four different chains, with a maximum of 500,000. Each parameter convergence was confirmed through visual inspections of the trace plots and autocorrelation plots. Additionally, the potential scale reduction (PSR) criterion [22] was lower than 1.05 for each parameter (where values lower than 1.10 assure chain convergence). BSEM model fit was assessed by means of the Posterior Predictive Checking (PPC). A PPC lower than .05 indicates poor fit, while values close to .50 and 95% PPC CIs that include zero values indicate a good model fit. DIC and BIC statistics are also reported, where lower values represent a better model fit.

Results

Participants

Sample characteristics by country are described in Table 1. Of the 700 survey respondents, 381 (54.4%) fulfilled the participation criteria. These included 161 Brazilian respondents, 78 Ugandan respondents, 86 Colombian respondents, and 56 British respondents.

Bayesian structural equation modeling

A partial approximate measurement invariance (PAMI) model was found to fit the data best and was preferred over several alternative models (exploratory factor analysis, classical confirmatory factor analysis, BCFA with informative priors over cross-loadings and BCFA with informative priors for cross-loadings and residual correlations; Appendix C). The PAMI model held factor loadings and items intercept equally across countries. There were two exceptions for Meaning and Competence, which were shown to be higher and lower for the United Kingdom, respectively. Therefore, the PAMI model resembled traditional partial scalar invariance models. The PAMI model successfully reproduced the factor pattern hypothesized by Huppert and So [4], including two additional cross-loadings: meaning for positive characteristics (PC) and positive emotion in positive functioning (PF; Table 2). Additionally, several minor residual correlations were found, as reported in Appendix C. Sensitivity analyses revealed that under more informative priors over item intercepts (e.g., using σ2 = .001 instead of σ2 = .01), these could be considered as equal across countries. Nevertheless, only the PAMI model applying σ2 = .01 prior is presented depicting the most conservative results found (Table 3).

Differences in latent means are further explored using the PAMI model (Table 4). This reflects how participants in each country scored on average on each well-being dimension. Firstly, participants from Colombia scored the highest in both PC and PF. Participants from Uganda scored the second highest in PC, but the lowest of all countries in PF. Participants from Brazil and the United Kingdom showed a similar response pattern, scoring lower than those from Uganda and Colombia in PC, but higher than those from Uganda and as high as those from Colombia in PF.

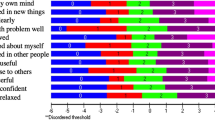

Five ways to wellbeing

In order to understand the relationship between the Five Ways and the two well-being factors, we ran two regression models that predicted the well-being score on each factor from the Five Ways. As before, approximate invariance was considered for the regression slopes (PPp = .06 (− 17.75, 162.91), DIC = 16,215.76, BIC = 18,058.79). Regression parameters for each country are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 1. Analysis showed that no regression coefficient significantly varied across countries. Previous findings regarding invariance of factor loadings and intercepts, and factor latent intercept interpretation remained unchanged.

Overall, the patterns found were similar for all countries. Learn and Connect were strong predictors of both PF and PC well-being factors for all countries. Give predicted PF in all countries, while Take Notice predicted PC in all countries. Lastly, Be Active was not a significant predictor of any of the well-being factors, except for PC in Brazil.

Discussion

This study investigated the properties of an improved version of Huppert and So [4] multidimensional well-being framework, with a particular emphasis in its cross-cultural and criterion validity. We expanded previous findings in the field in three main areas: a) the psychometric properties of the scale items, as we ensured item time and response scale consistency across items; b) the generalizability of the model to non-European areas, by testing Huppert and So [4] model in geographically diverse regions beyond those that participated in the original study; c) we investigated the extent that each well-being factor was connected with five different behavioural markers of well-being. This work suggested that improving the assessments of well-being allowed for more nuanced evaluations and better identification of areas for improvement, and its usefulness to inform future policies and well-being interventions.

One of the key strengths of this research is that we have adapted the items used in the ESS Round Six to improve internal consistency. Temporal consistency was achieved by setting all items within the same timeframe, addressing concerns that temporal inconsistencies between items may lead to a distorted measure of life satisfaction that unduly combines information from different time periods [23]. As a result, the survey items presented here, while comparable to the ESS Round Six items, represents an improvement in terms of consistency, which makes them preferable for future use and data collection. We further replicated the original model, including the distinction between “Positive Functioning” (PF) and “Positive Characteristics” (PC), as well as their respective item loadings. Only two domains (“Positive Emotion” and “Meaning”) were found to load on both factors. However, the presence of such cross-loadings was already suggested in the exploratory solution presented by Huppert and So’s (Table 3 [4];). Thus, the proposed scale was able to capture the original theoretical model while improving its psychometric properties.

By employing a novel, methodologically sound framework (i.e., Bayesian approximate measurement invariance) for testing cross-cultural invariance, this research advanced that the multidimensional well-being framework proposed by Huppert and So [4] could potentially replicate in non-European regions. Our results suggest that the multidimensional well-being framework originally suggested by Huppert and So [4] could be explored in future research including larger, representative and diverse samples with a higher degree of confidence, given the psychometrics improvements here presented. Moreover, this research highlights the necessity of continuing to improve well-being assessments tools under different contexts.

Our results also suggest the existence of regional differences for both well-being dimensions, which could be further explored for local policy precision, but are still useful for macro level monitoring. What would further add to local policy is that results indicate that not all Five Ways were similarly related with both well-being factors. Moreover, the specificity with which each “way” affects the two well-being domains highlights this well-being measurement’s potential for evaluating policy actions. Naturally, this should only be applied for fully powered and focused samples. Such research endeavours should aim to confirm or discard the differences in patterns observed here. Nevertheless, the proposed scale and the Huppert and So’s [4] model (with various revisions and iterations) remains useful in broad policy research investigating the relationship between different well-being predictors and specific components of this construct.

Limitations

This research is subject to a number of limitations, many of which have been previously outlined in Huppert and So’s [4] original research. For example, the scales have not been extended to include constructs fundamental to certain conceptualisations of well-being, including Autonomy, which is considered central to certain theoretical models [24,25,26,27], the psychodynamic domains of “personal-growth”, and “self-acceptance” [26]. As formerly noted by Huppert and So, Autonomy might be a dimension that is particularly sensitive to different cultural and societal norms, specifically when considering the balance between individualism and collectivism, and as such might not be considered as necessary to well-being in all societies. Although the questionnaire was also translated into Arabic and French with the aim of collecting data in North Africa, this intention proved impossible to realise within the timeframe of this research.

The study was designed such that the opening demographic questions were in English, which necessarily excluded individuals who do not speak the languages in certain countries and thus could have been a source of bias. Furthermore, the age requirement for the participants means that whilst an equivalency has been found for a sub-population, the scales might not be equivalent within the whole population. Lastly, it would be important to study in further detail cross-country differences observed in the PAMI model, such as United Kingdom individuals scoring higher in Meaning and Competence items.

Conclusions

In summary, this research aimed to improve multidimensional well-being assessments by enhancing Huppert and So’s [4] proposed items. The proposed assessment tool has a number of benefits: (a) the items in the scale have a theoretically sound rationale for inclusion, and have been (b) critically evaluated and refined across different studies, (c) the scale itself is short, reliable and valid, (d) and has been found to be cross-culturally invariant across limited European, South American and Eastern African populations. As a result, it provides a time-efficient measure that can capture how different policies may influence specific aspects of well-being, offering insights beyond single-item well-being measures (e.g., life satisfaction or happiness).

One of the reasons why valid, reliable, and robust measures of well-being are critical is that such instruments are necessary to identify potentially unmet needs in a population. Naturally, truly comprehensive measures would cover wider and culturally or contextually specific items, but for high level national surveying, the instrument presented in this study does offer insight for policy and other interventions to tackle unmet needs on a population level. These findings contribute to the improvement of well-being measures for informing policy decisions on local, national, and international levels. We argue that using this consistent, fully aligned, and temporally coherent approach to measurement offers an improvement on existing measures. Moreover, evidence suggests that the scale represents a valid tool for assessing well-being, with further testing needed in additional countries and cultures.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available from the author on request since this is a mental health study and was carried out prior to data sharing requirments. We are happy to provide subsets of anonymised cases on request.

References

Diener E, Seligman MEP. Beyond Money: Progress on an Economy of Well-Being. Perspectives Psychological Sci. 2018;13(2):171–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616689467.

Dolan P, White MP. How can measures of subjective well-being be used to inform public policy? Perspectives Psychological Sci. 2007;2(1):71–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00030.x.

Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J. Report of the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social Progress (CMEPSP); 2009.

Huppert FA, So TTC. Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc Indic Res. 2013a;110(3):837–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7.

Diener E, Diener M, Diener C. Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):851–64 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.851.

Lyubomirsky S, Lepper H. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:137–55.

Diener E, et al. New Measures of Well-Being. In: Diener E, editor. Assessing Well-Being. Social Indicators Research Series, vol. 39. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Hills P, Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality Individual Differences. 2002;33:1073–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00213-6.

Dolan P, Peasgood T, White M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J Economic Psychology. 2008;29(1):94–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001.

Huppert, F.A., Marks, N., Clark, A. E., Siegrist, J., Stutzer, A. Vittersø, J. & Whrendorf, M. (2008) Measuring well-being across Europe: Description of the ESS Well-being Module and preliminary findings (Working Paper N° 2008–40). Retrieved from HAL website: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00586267/document.

New Economics Foundation. Happy Planet Index. 2016a:2016 Retrieved from: http://happyplanetindex.org/countries.

New Economics Foundation. Looking through the Wellbeing Kaleidoscope. Results from the European Social Survey, 2016b Retrieved from https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/3e7752db1667d8adf2_hjm6iwz1u.pdf.

Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project. Final Project report. London: The Government Office for Science; 2008.

Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Bayesian SEM: a more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychol Methods. 2012;17:313–35.

Kim ES, Cao C, Wang Y, Nguyen T. Measurement Invariance Testing with Many Groups: A Comparison of Five Approaches. Structural Equation Modelling. Multidisciplinary J. 2017a;24(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1304822.

Kim ES, Cao C, Wang Y, Nguyen T. Measurement invariance testing with many groups: a comparison of five approaches. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2017b;24(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1304822.

Muthén B, Asparouhov T. BSEM measurement invariance analysis. Mplus Web Notes: No 17 January 11, 2013; 2013b.

Muthén, B.O. & Asparouhov, T. BSEM measurement invariance analysis. Mplus Web Note No. 17; 2013a http://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnote.shtml.

Muthen LK, Muthen B. Mplus User's Guide. 7th. ed. Los Angeles: CA Muthen & Muthen; 2012a.

Muthen LK, Muthen B. 1998–2012, Mplus User's guide (7th ed.). CA Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles; 2012b.

Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall; 2014a.

Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164.

Jahoda M. Current concepts of positive mental health: New York Basic Books; 1958.

Ryan RM, Deci LE. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and Eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):141–66.

Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(4):719.

Marsh HW, Morin AJS, Parker PD, Kaur G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: an integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:85–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700.

Chiorri C, Day T, Malmberg LE. An approximate measurement invariance approach to within-couple relationship quality. Front Psychol. 2014;5(983). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00983.

Millsap RE. Statistical approaches to measurement invariance. London, England: Routledge; 2011. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203821961.

Davidov E, Cieciuch J, Meuleman B, Schmidt P, Algesheimer R, Hausherr M. The comparability of measurements of attitudes toward immigration in the European social survey: exact versus approximate measurement equivalence. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2015;79:244–66.

Van de Schoot R, Kluytmans A, Tummers L, Lugtig P, Hox J, Muthén B. Facing off with Scylla and Charybdis: a comparison of scalar, partial, and the novel possibility of approximate measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, article 770. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00770.

Cieciuch J, Davidov E, Schmidt P, Algesheimer R, Schwartz SH. Comparing results of an exact. Vs an approximate (Bayesian) measurement invariance test: a cross-country illustration with a scale to measure 19 human values. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, article 962. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00982.

De Bond N, Van Petegem P. Psychometric evaluation of the Overexcitability questionnaire-two applying Bayesian structural equation modeling (BSEM) and multiple-group BSEM-based alignment with approximate measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, article 1963. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01963.

Zercher F, Schmidt P, Cieciuch J, Davidov E. The comparability of the universalism value over time and across countries in the European social survey: exact vs approximate measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, article 733. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00733.

Van de Schoot R, Broere J, Perryck KH, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg M, van Loey NE. Analyzing small data sets using Bayesian estimation: the case of posttraumatic stress symptoms following mechanical ventilation in burn survivors. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6. Article 25216. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.25216.

Van Erp S, Mulder J, Oberski DL. (conditionally accepted). Prior sensitivity analysis in default Bayesian structural equation modeling. Psychol Methods. 2017;23(2):363.

Asparouhov T, Muthén B, Morin AJS. Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual Covariances. J Manag. 2015;41(6):1561–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315591075.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Eduardo Garcia-Garzon is funded through Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain (Grant FPU 15/03246). Tomas Folke is funded through the UK Research and Innovation GCRF RESEARCH FOR HEALTH IN CONFLICT (R4HC-MENA); developing capability, partnerships and research in the Middle and Near East (MENA) ES/P010962/1. This study was supported in part by the UK Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/LO14629/1 as well as through the UKRI-GCRF ES/P010962/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGBN, AB and KR made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, EGG and TF were critical in the interpretation of data. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Department of Psychology Ethics Committee (PEC), University of Cambridge. Consent was obtained from all participants, and a debrief was presented upon completion of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A Global Mental Health Measurement Survey (English Translation)

Participant Consent

The following survey seeks to assess general measures of well-being, which will be used to inform policy in that area. All we ask is about five to ten minutes to answer 20 simple questions on the subject. There is nothing hidden in this study: you will be presented with a series of questions and simply asked to choose the answer you deem most appropriate. Nothing personal is requested, and there are no right or wrong answers.

Once you have submitted all items, you will receive a score that gives you information about the types of answers you have given. However, there are no right or wrong answers - these are simply your choices. This is not a clinical study, and therefore the score is not a formal health assessment.

If you have questions, please contact Kai Ruggeri at dar56@cam.ac.uk. Your responses will only be used for the purposes of research that may eventually inform policy. Nothing personal is requested or stored.

Data will not be shared outside the Policy Research Group in the Department of Psychology at the University of Cambridge. By clicking the ‘Next question’ button below, you consent to complete the study and having your results analysed within this study. You may stop at any time and any unanswered questions will not be included.

Q1. In what year were you born?

Q2. Which gender are you?

-

Male

-

Female

-

Prefer not to say

-

Other

Q3. What is your primary nationality?

Q4. What is your primary country of residence?

Q5. Which employment status is most applicable to you?

EDIT: If you are a full-time student who works part-time, please choose Education. If you are a full-time employee that studies part-time, please choose Employed. If you are unsure, please simply choose the option you feel BEST describes you.

A) Employed (full-time, part-time, self-employed, temporarily away or working for your family business).

B) In education (not paid by for an employer) (EDIT: ‘for’ was included after the survey was already being circulated).

C) Unemployed, and actively looking for a job.

D) Unemployed, wanting a job but not actively looking for a job.

Q6. How many years of education have you completed, whether full-time or part-time? EDIT: Please report in full-time equivalents and include compulsory years of schooling, including primary, secondary and any post-secondary (university, vocational) formal education.

Please select your native languages:

-

English

-

French

-

Spanish

-

Portuguese

Arabic

Please rate how strongly you agree or disagree with the following statements.

1-Could not disagree more.

2-Strongly disagree.

3-Disagree.

4-Neutral.

5-Agree.

6-Strongly agree.

7-Could not agree more.

In general…

1. I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do.

2. I feel calm and peaceful.

3. I feel absorbed in what I am doing.

4. I feel what I do in my life is valuable and worthwhile.

5. I am optimistic about my future.

6. I feel happy.

7. I receive help and support from people I am close to when I need it.

8. I recover quickly from things that go wrong in my life.

9. I feel positive about myself.

10. I feel full of energy.

11. I feel I am free to decide for myself how to live my life.

12. I am able to take advantage of the good things in my life.

13. I pursue opportunities to try new things.

14. I take time during my daily activities to appreciate my surroundings.

15. I give help and support to those close to me.

16. I am spending time socialising with friends, peers and other people close to me.

17. In a typical week, how many days are you active for at least 30 min? Active means are doing enough to raise your breathing rate.

0 days.

1 days.

2 days.

3 days.

4 days.

5 days.

6 days.

7 days.

Debrief:

Thank you for your time. For further information, please visit our website:

http://www.psychol.cam.ac.uk/pol-res-group/projects

What your score means:

This survey does not diagnose mental illness. It can only give an indication of whether you are carrying out certain activities recommended by psychologists to promote flourishing and wellbeing.

30–35/35: Excellent.

You are engaging in many of the activities recommended improving your mental health and wellbeing.

25–29/35: Very good.

You carry out many of the activities recommended to improve your mental health and wellbeing and could think about engaging in them even further.

20–24/35: Good.

You engage in some of the activities recommended for improving your mental health and wellbeing, but you could do more!

0–19/35: Room for improvement.

You might want to consider whether there are ways you could fit activities that enhance wellbeing into your daily routine.

Appendix B Global Mental Health Measurement Survey (Foreign translations of core questions)

To come to the final foreign translations, World Health Organisation guidelines on the process of translation were followed. This comprises:

-

Forward translation

-

Back translation

-

Pre-testing

-

Final version

However, contrary to the guidelines, the back translation results were not reviewed by an ‘expert panel’ but merely commented on by native speakers of each languages. Furthermore, pre-testing did not involve their minimum of ten individuals but ranged from 2 to 5 native speakers of each languages.

This appendix includes the final version translation for each languages.

Note: In this initial pilot study, the French and Arabic versions were not in fact used due to difficulties or delays in testing in regions where these were the primary languages.

French.

1. Je me sens calme et serein(e).

2. Ce que je fais me donne un sentiment de réussite.

3. Je me sens absorbé(e) par ce que je suis en train de faire.

4. J’ai le sentiment que ce que je fais dans ma vie a de la valeur et est. utile.

5. Je suis optimiste par rapport à mon avenir.

6. Je me sens heureux.

7. Je reçois l’aide et le soutien de mes proches en cas de besoin.

8. Je retombe rapidement sur mes pieds quand les choses tournent mal dans ma vie.

9. J’ai une image positive de moi-même.

10. Je me sens plein(e) d’énergie.

11. Je me sens libre de décider moi-même comment vivre ma vie.

12. Je sais profiter des bonnes choses dans ma vie.

13. Je recherche des occasions d’apprendre de nouvelles choses.

14. Je prends le temps d’apprécier mon environnement pendant mes activités quotidiennes.

15. J’apporte de l’aide et du soutien à mes proches.

16. Je passe du temps avec mes amis, pairs, et autres de mes proches.

17. Dans une semaine ordinaire, combien de jours pratiquez-vous une activité physique pendant au moins 30 min? Ici, une activité physique suffisamment intense pour entrainer une hausse de votre rythme respiratoire.

Scale:

- Tout a fait en désaccord

-

Fortement en désaccord

-

En désaccord

-

Ni d’accord, ni en désaccord

-

D’accord

-

Fortement d’accord

-

Tout a fait d’accord

Spanish.

1. Siento una sensación de logro por lo que hago.

2. Me siento tranquilo/a y relajado/a.

3. Me siento implicado/a en lo que hago.

4. Siento que lo que hago en mi vida tiene valor y vale la pena.

5. Soy optimista con respecto a mi futuro.

6. Me siento feliz.

7. Recibo ayuda y apoyo de las personas más cercanas a mi cuando lo necesito.

8. Me recupero rápidamente de las cosas que salen mal en mi vida.

9. Me siento bien conmigo mismo/a.

10. Me siento rebosante de energía.

11. Tengo la sensación de poder decidir con libertad como vivir mi vida.

12. Busco oportunidades para aprender cosas nuevas.

13. Tomo tiempo durante mis actividades diarias para apreciar mi entorno.

14. Presto ayuda y apoyo a las personas cercanas a mi cuando lo necesitan.

15. Paso tiempo en compañía de amigos, compañeros y otras personas cercanas.

16. Consigo aprovechar las cosas buenas de mi vida.

17. En una semana típica, ¿cuantos días estás activo/a durante al menos 30 minutos? Active significa hacer lo suficiente para aumentar la frecuencia respiratoria.

Scale:

-No podría estar más en desacuerdo.

-Muy en desacuerdo.

-En desacuerdo.

-Ni de acuerdo ni en desacuerdo.

-De acuerdo.

-Muy de acuerdo.

-No podría estar más de acuerdo.

Portuguese.

1.Sinto- me realizado (a) com o que faco.

2. Sinto-me calmo(a) e tranquilo(a).

3. Sinto-me absorvido(a) por aquilo que estou a fazer.

4. Sinto que o que faco na minha vida tem valor e vale a pena.

5. Sou otimista em relacao ao meu futuro.

6. Sou feliz.

7. Recebo apoio e ajuda das pessoas que sao proximas de mim quando preciso.

8. Eu me recupero rapidamente quando as coisas dao errado na minha vida.

9. Eu me sinto positivo(a) em relaco a mim mesmo(a).

10. Sinto-me cheio(a) de energia.

11. Sinto que sou livre para decidir por mim proprio(a) como viver a minha vida.

12. Eu procuro oportunidades para experimentar coisas novas.

13. Eu tomo o tempo durante minhas atividades diárias para apreciar meus arredores.

14. Dou apoio e ajuda as pessoas que sao proximas de mim quando elas precisam.

15. Eu passo tempo socializando com amigos, colegas e outras pessoas perto de mim.

16. Consigo aproveitar as coisas boas na minha vida.

17. Em uma semana típica, quantos dias você está ativo/a por pelo menos 30 minutos? Ativo significa fazer o suficiente para aumentar a taxa de respiração.

Scale:

-Eu nao poderia discordar mais.

-Discorda muito.

-Discorda.

-Nem concorda nem discorda.

-Concorda.

-Concorda muito.

-Eu nao poderia concordar mais

Appendix C: Statistical Analyses

Due to the high volume of tested models, only a brief commentary of the outputs is presented here. Appendix C is further divided into three main sections. Firstly, a brief introduction of the statistical reasoning behind Bayesian SEM and approximate measurement is made. Second, the model results are succinctly commented on. Thirdly, the results from sensitivity analysis are presented. Detailed results of each model are available on request, which includes the input code and model results.

1. Statistical approach.

2. Model results.

3. Sensitivity Analyses.

Statistical approach.

Bayesian Structural Equation Modelling.

Traditional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) measurement models often represent the simplest structure, where each item is only allowed to load in one factor, with both remaining cross-loadings and residual covariance between items fixed to zero. Unfortunately, this practice has been deemed inadequate, and it is recommended that it be avoided [28]. Alternatively, Bayesian Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling (BSEM) provides a solid framework for estimating measurement models and studying measurement invariance which has shown to overcome some of the limitations associated with traditional techniques and represents a mixture between confirmatory and exploratory approaches [15, 18, 19]. Furthermore, it applies the benefits of Bayesian estimation with regards to parameter and model estimation. Given space limitations, readers interested in Bayesian inference in measurement invariance can refer to Chiorri, Day and Malmerg [29], and Kim, Cao, Wang and Nguyen [16, 17] among others.

The idea behind BSEM models is to use Bayesian inference to avoid fixing parameters to zero (as in CFA). Instead, such parameters (i.e., cross-loadings or residual variances) are given an “informative, small-variance priors” ([15], p.316), which reflects the possibility for these parameters to take small values around zero (i.e., absolute value .20). Such small deviations from zero are to be realistically expected, and generally lead to the improved estimation of factor structures [18, 19, 28].

Approximate measurement invariance.

Similarly, traditional measurement invariance is studied by means of applying Multi-Group CFA (MGCFA), where a set of nested models are fitted by restricting certain groups of parameters to be equal between groups: (a) configural invariance model (equal factor structure across groups, different factor loadings, intercept and residual variances); (b) metric model (factor loadings are now constrained to be equal across countries); (c) scalar invariance (loadings and intercepts are restricted to be equal across groups). To fulfil this research’s objective (i.e., to compare latent means across countries) scalar invariance is to be achieved, as it indicates that differences in means and covariates of indicators are solely due to latent factor distribution differences [18, 19, 30]. Unfortunately, strict measurement invariance models are often incorrectly rejected based on poor model fit. Nevertheless, such situation is often caused from small deviations that do not interfere with the establishment of measurement invariance across groups [31, 32]. BSEM substitute the notion of zero difference across groups underlying MGCFA for approximate zero differences if factor loadings and item intercepts, applying cero-centred, small-variance priors [18, 19]. Simulation studies results showed that BSEM approximate invariance had been shown to be equal or superior to traditional alternatives [16,17,18,19, 32], and it has been successfully applied in many studies (e.g., [29, 32,33,34,35]). Additionally, BSEM provides a reliable alternative to parameter estimation when dealing with limited sample sizes, as in our case [36, 37].

Statistical approach.

Our analysis approach was performed as suggested by Muthén & Asparouhov [18, 19] and Kim [16, 17]: First, BCFA and traditional CFA models were fitted. Additionally, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) model was specified to inspect an unrestricted solution where cross-loadings are freed, but not residual correlations. Accordingly, these two models represent a theoretically-driven restricted solution (CFA), an unrestricted measurement model (EFA), and an intermediate model where all factor loadings and residual correlations are estimated, but with parameters expected to be close to zero by the theory being shrunk to that value (BCFA).

Three BCFA models of interest were explored: Firstly, a model resembling CFA zero-restrictions for cross-loadings and residual inter-item correlations was explored. Default Mplus non-informative priors were specified for factor loadings, factor variance and the correlation of the factor. Secondly, a BCFA model where cross-loadings were given normal informative priors with zero means and .01 variances (bounding 95% cross-loading posterior distribution to be within .20) was explored. Thirdly, residual correlations were additionally explored using specifying informative priors. Priors explored included Inverse Wishart distributions with df = 16 (corresponding to zero mean, .01 variances [34];). Sensibility studies for the Inverse Wishart distribution are reported in the third section of this appendix. Second, approximate measurement invariance for the best-fitting model from the first was explored using specifying informative priors (normal distribution with zero-mean and .01 variance parameters) on factor loading and item intercept differences between countries. Again, sensitivity analysis for variance differences is presented later. The remaining parameters were given uninformative parameters as in Muthén & Asparouhov [15]. This model allows us to inspect if any parameter (either factor loadings or factor intercepts) was to be considered as non-invariant. In our last model, all the invariant parameters are restricted to be strictly similar across groups (exact invariance), with non-invariant parameters given informative priors (approximate invariance). Therefore, this model becomes a partial approximate measurement invariance model. Factor means and factor variances for the last group (Uganda) were fixed to zero and one, respectively, in order to identify the model.

Lastly, to understand the effect of the Five Ways to Well-being on positive functioning and positive characteristic, the CFA, EFA and BCFA models were expanded to SEM, ESEM and BSEM models, respectively. Similarly, to previous analyses, SEM represents a restricted, theory-driven solution where non-expected parameters are restricted to zero (i.e., cross-loadings and residual correlations). ESEM represents a new perspective where an SEM model with an EFA measurement model is computed. Therefore, it represents an unrestricted approach where all cross-loadings, but no residual correlations, are freed. To compute the BSEM model, the measurement model used was the AMI model previously estimated.

Computation details.

All models were estimated in Mplus 7 [15]. CFA models were fitted using a robust maximum likelihood estimator. EFA and ESEM models were fitted using a robust maximum likelihood with oblique target rotation. BCFA models were sampled in four different chains, applying a maximum of 500,000 iterations or chain convergence was reached, with no thinning applied.

Model fit and convergence criteria.

Each parameter convergence was confirmed by visual inspections of trace plots and autocorrelation plots. Additionally, the potential scale reduction (PSR) criterion [22] was ensured to be lower than 1.05 for each parameter. Values lower than 1.10 indicate that the MCMC chain has successfully converged into its target distribution. After convergence was assured, each model fit was assessed as follows: For CFA models, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) fit indexes were evaluated. CFI and TLI values over .95 and RMSEA values lower than .05 indicate a good model fit. BSEM models were assessed using the Posterior Predictive Checking (PPC). A PPC lower than .05 indicates poor fit, while values close to .50 and 95% PPC CI including zero value indicate good model fit. The Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) statistics are also reported, where lower values represent a better model fit.

Model Results.

Traditional confirmatory analyses.

Table 6 indicates each model fit. As expected, the traditional CFA measurement model did not fit the data well when evaluating model fit statistics. Logically, the fully exploratory model showed an improved model fit and was considered to have a good fit as measured by CFI, TLI and RMSEA statistics.

Bayesian Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Neither BCFA models with cross-loadings and residual variances fixed to zero (BCFA1) or BCFA model with informative prior for cross-loadings and residual variances fixed to zero (BCFA2) provided a good fit to the data. Unsurprisingly, the last model (BCFA3) including informative prior for both cross-loadings and residual variances, showed a good fit to the data. The model fitted the data even when applying more informative priors (see next section). Huppert and So’s [4] factor structure was fully reproduced with five additional cross-loadings (meaning and positive relationships in positive functioning and emotional stability, optimism and positive emotion in positive characteristics). A total of 31 residual correlations were found as relevant (95% credibility interval does not cover zero), with a mean absolute value of .14 (range of −.26 to .19). Moreover, the two factors were positively correlated (r = .31, .95% CI = .22–.40; Table 7). Lastly, DIC and PPp values showed that the BCFA3 model should also be preferred to both BCFA1 and BCFA2 models. Even though BIC indicates that BCFA2 is the model representing best model fit, Asparouhov, Muthén & Morin [38] have strongly argued that the DIC statistic should be favoured when comparing BSEM parameters using strong, informative priors.

Bayesian Approximate Measurement Invariance.

Metric and scalar invariance (the latter being necessary before comparing group latent means) were explored using establishing informative priors over group differences for factor loadings and factor intercepts, respectively. Both, metric and scalar invariance were successfully established, as reflected by the adequate model converge and fit (Table 8). Sensitivity analyses (following section) revealed that modifying the prior over group differences for either factor loadings or intercepts revealed adequate fit even for more informative priors. Parameter estimations for each group are available in model files.

When inspecting model results under the most uninformative prior (i.e., N(0,.01)), two non-invariant parameters were identified. In the case of the United Kingdom, the intercept of meaning was higher while the intercept of competence was lower than the between-group average (95% CI of the difference did not cover zero). These observed differences disappear when using a more informative prior (N (0,.001)) over intercept differences. Alternatively, as suggested by Muthén and Asparouhov [18, 19], a partial approximate measurement model (PAMI), where only these two intercepts were given informative prior over their differences, and the other parameters were constrained to be equal, was fitted. This model fitted the data better than the AMI model attending the BIC criterion but provided the worst fit to the data as suggested by an increasing DIC and lower PPp values.

SEM model including the Five Ways.

A traditional SEM model including the Five Ways as predictors of the two factors of well-being did not fit the data adequately. Alternatively, even though the ESEM improved SEM model fit it did not show a good TLI or RMSEA indexes. Following inadequate, but extended practices on the field, an ESEM model (ESEM-MI) freeing parameters as suggested by modification indexes until achieving adequate TLI model fit was tested for the sake of comparison. Three additional residual variances were freed (covariances for pairs optimism with meaning, positive relationships with positivity and positive relationship with vitality). This model showed a barely adequate model fit to the data.

BSEM model invariance when including the Five Ways.

Given that no traditional alternative provided a compelling alternative, an approximate measurement invariance model was fitted in order to understand countries differences for the regression parameters. Therefore, a BSEM-AMI model was tested. This model provided an adequate fit to the data (PP. = .16; 95% CI (−.17.75; 162.91); DIC = 16,215.76; BIC = 18,058.79).

Sensitivity Analyses.

Sensitivity analyses for the BCFA3 model are presented. Table 10 shows that varying the informativeness of the prior settled over the variance term for the residual variance terms from 16 df to 70 df provided an acceptable fit to the data. Remarkably, the model which provided a better fit to the data, according to DIC and BIC statistics, was a BCFA model with an IW distribution with 20 degrees of freedom.

Table 11 presents a sensitivity analysis for the normal distribution prior set over the variance parameters of the differences for the groups in the PAMI model. All tested models provided an acceptable fit to the data, even when applying a normal prior with variance parameter as lower as 10− 4. The preferred model, following BIC indications, was the model including a prior normal distribution with .01 variance parameter.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Graeff-Buhl-Nielsen, S., Garcia-Garzon, E., Benzerga, A. et al. Global mental health: an improved measure of well-being in multiple languages. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18, 209 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01375-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01375-3