Abstract

Background

Tele-harm reduction (THR) is a telehealth-enhanced, peer-led, harm reduction intervention delivered within a trusted syringe services program (SSP) venue. The primary goal of THR is to facilitate linkage to care and rapid, enduring virologic suppression among people who inject drugs (PWID) with HIV. An SSP in Miami, Florida, developed THR to circumvent pervasive stigma within the traditional healthcare system.

Methods

During intervention development, we conducted in-depth interviews with PWID with HIV (n = 25) to identify barriers and facilitators to care via THR. We employed a general inductive approach to transcripts guided by iterative readings of the raw data to derive the concepts, themes, and interpretations of the THR intervention.

Results

Of the 25 PWID interviewed, 15 were in HIV care and adherent to medication; 4 were in HIV care but non-adherent; and 6 were not in care. Themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis included the trust and confidence PWID have with SSP clinicians as opposed to professionals within the traditional healthcare system. Several barriers to treatment were reported among PWID, including perceived and actual discrimination by friends and family, negative internalized behaviors, denial of HIV status, and fear of engaging in care. Facilitators to HIV care included empathy and respect by SSP staff, flexibility of telehealth location, and an overall destigmatizing approach.

Conclusion

PWID identified barriers and facilitators to receipt of HIV care through the THR intervention. Interviews helped inform THR intervention development, centered on PWID in the destigmatizing environment of an SSP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

People who inject drugs (PWID) are at an increased risk for HIV infection due to both syringe sharing and sexual risk behaviors [1] compounded by competing priorities related to unstable housing and sex work [2,3,4,5]. Unfortunately, PWID face substantial barriers to HIV diagnosis, linkage to care, retention in care, and viral suppression [6,7,8]. Individuals retained in HIV care have a higher likelihood of viral suppression and lower mortality [9]. Stigma is a key barrier to HIV care among PWID [10]. Perceived and experienced discrimination from family and community members can discourage PWID with HIV from seeking medical care [11]. Additionally, internalized stigma can prevent PWID with HIV from accessing services [12]. Both internal and external stigma and experiences with rejection can create fear of disclosing HIV status, further impacting retention in care [5,6,7,8,9,10, 13, 14].

In cases where PWID have access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), poverty, substance use disorders, mental health disorders, social stigma, and medication side effects can limit adherence. Most patients with HIV report more than one barrier to ART adherence [15]. The HIV care continuum among PWID is disproportionally impacted by social determinants of health, including homelessness, discrimination, and medical distrust [16, 17] with only one in two PWID with HIV virally suppressed in the USA [18, 19].

Effective interventions for reducing HIV transmission among PWID include the provision of drug injection equipment through syringe services programs (SSPs) [20, 21]. SSPs can mediate access to health care services; but, in some cases, implementation has been constrained by law enforcement activities [22]. The evidence is clear: when SSPs were used in combination with other prevention interventions following injection drug-associated HIV outbreaks, there are significant declines in incident HIV infections [23, 24]. However, few studies [25, 26] focus on the relationships between PWID and community members in recovery from addiction, specifically peer workers with lived experience of substance use working at SSPs.

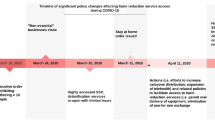

Telehealth has been used to increase access to HIV care for patients who experience challenges along the HIV care continuum, improving their adherence and retention [27]. Residing in the U.S. city with the highest rate of new HIV infections, the IDEA SSP in Miami, Florida, has previously shown how services can be leveraged for linkage to HIV care and substance use treatment [28, 29]. Partnership with the Florida Department of Health has facilitated HIV testing and rapid access to ART [26, 30, 31]. To build on this foundation, we developed Tele-Harm Reduction (THR) to facilitate access to HIV care within the non-stigmatizing environment of a harm reduction setting [32]. The purpose of this qualitative analysis was to identify experiences, perceptions, barriers, and facilitators for engagement of PWID with HIV in care via a THR model. Participants that were interviewed were actively participating in the THR model or had knowledge of the THR pilot intervention and were using SSP services at the time.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Miami (IRB# 20190893). All data were de-identified and anonymous.

Tele-harm reduction intervention

THR has been described in greater detail elsewhere [22]. In brief, tele-harm reduction has two components, meeting PWID where they are physically and emotionally. In component 1, PWID are connected to a physician to initiate ART via telehealth wherever they are (e.g. SSP, mobile unit, encampment). In component 2, a peer with lived experience facilitates ongoing telehealth visits with the physicians and psychologist. Peers may also support adherence by delivering medications stored at the SSP and providing ongoing motivational interviewing.

Recruitment and participants

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling methods. Inclusion criteria included: (1)18 years of age or older, (2) enrollment at the IDEA Miami SSP, (3) testing reactive via HIV rapid test, (4) reported history of injection drug use, and (5) English- or Spanish-speaking. Pregnant participants were excluded because they may have a unique and non-generalizable experience accessing HIV care. Some interviewees (n = 17) were already participating in the THR pilot intervention.

Semi-structured interviews

After anonymous verbal consent, semi-structured interviews were conducted by a research assistant with previous training in qualitative interviewing and experience working with PWID. Interviews were completed both at the IDEA Miami SSP fixed site and mobile unit in a private setting. Interviews ranged between 15 to 30 min and were audio recorded. Questions were designed to be open-ended, and the interview guide focused on barriers to engagement in HIV care and recommendations for the telehealth intervention, including facilitator characteristics and training. We ascertained knowledge and attitudes regarding HIV treatment for PWID, barriers and facilitators to medication adherence, and long-term retention in HIV care. Table 1 shows the domain and corresponding sample interview questions. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim by an external transcription company.

Procedure and data analysis

We employed a general inductive approach to understand the barriers and facilitators to care for PWID with HIV at an SSP as presented in the transcribed interviews. A general inductive approach is commonly used in the health and social sciences and allows findings to emerge from the most frequent and dominant codes and themes encountered throughout the analysis [33]. Authors were guided by the interview transcripts to derive the concepts, themes, and interpretations on the objectives.

Following a general inductive approach, CS read all the transcripts while BH, YR, and HA each read two different transcripts. A codebook was created that included code names, definitions, sample quotes, and coding decision rules. The approach entailed data exploration, inductive coding, and thematic analysis. Transcripts were read, re-read, and coded in an iterative fashion. An initial list of themes and subthemes were created. Data saturation was met after the 10th transcript when no new themes or subthemes emerged. Coders then coded one transcript together, discussing coding discrepancies, and adjusting coding decision rules and definitions accordingly. The coding pairs coded transcripts and calculated percent agreement based on consistency of ratings against the lead author (CS). The percentage agreement was calculated to ensure interrater reliability of the codebook. Initial rating of agreement between coding pairs ranged between 90 to 97% on independently coded transcripts, with coding pairs reaching 100% on all final codes.

All final codes were analyzed in Dedoose (Version 8.2.14, Sociocultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, CA). Specifically, code frequencies were extracted, which allowed for identification of the most highly endorsed codes in the data. Then, the information was extracted on code-cooccurrence to understand the number of times two or more codes appeared together in the same excerpt. Lastly, excerpts from each code were discussed to validate the data and codes and gather sample quotations for our themes and subthemes. To improve the quality of the research and ensure explicit and comprehensive reporting of findings, the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist guided the reporting of study methods and results [34].

Results

There was a total of 25 participants recruited that included 15 participants in HIV care and adherent to medication, 4 in HIV care but non-adherent, and 6 not in care. Age ranged from 23 to 67 years of age (with a mean age of 31 years old); 12 were males, 11 were females. Two participants had missing demographic data (Table 2). Of the 25 participants, 17 (68%) were patients who had received the THR pilot intervention and the remaining 8 participants were using SSP services and had knowledge of the THR pilot intervention.

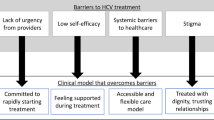

A total of 34 themes were applied 770 times in the 25 transcripts. Themes that appeared most frequently included HIV care, accessing care, confidence in medical doctors, discrimination, medication adherence, negative acceptance by peers, and syringe exchange. Codes that co-occurred the most were: medication adherence and HIV care; syringe exchange and HIV care; negative acceptance by peers and discrimination; syringe exchange and accessible physical location of medical office. Overall, we lumped codes into two themes: barriers to HIV care for PWID and facilitators to engagement, and their corresponding sub-themes (see Fig. 1). Representative quotations from 22 excerpts are provided to ensure substantial evidence of the thematic findings.

Negative experiences outside syringe exchanges with HIV services

Personal attitudes and beliefs: denial of HIV status and internalized stigma

The most common response when asked about barriers to receiving HIV care pertained to participants’ denial or avoidance of their HIV status upon initial diagnosis. Participants frequently reported the fear of being judged due to their HIV status and avoiding certain behaviors or stereotypical locations that would label them as someone who has HIV, such as attending an HIV clinic. Many described waiting until they really had to seek medical treatment to start their care:

“My fear was really bad. I hardly felt comfortably and hardly talked to anyone at all until I ended up having something happen to me that was pretty life threatening or whatever, I was just like, well I gotta start talking. I gotta start doin’ something. I was just so afraid when I found out that I was positive.”

“I didn’t do anything about my HIV until I had to.”

“I didn’t want other people to know. I knew that other people who were using drugs would spread the word that they saw me there and obviously I must have it. That was my biggest fear.”

Adherence to medication and doctor’s order: avoidance of medical care in a regular clinical setting

Participants reported difficulty adhering to medication and appointments prior to using the mobile THR pilot due to medical mistrust and mistreatment by professionals. Participants reported mistreatment or humiliation that they encountered at prior medical visits and its effect on their self-esteem and desire for ongoing treatment:

“Everywhere else I've gone, even where I’m staying right now, I was even in a treatment facility, treated me like crap. They don’t help. Even if they have information, they won’t help. I’ve been asking this lady, I signed up for a program and she wants nothing to do with me. It’s a long story, but it had to do with my HIV.”

“The lady that was getting ready to do my blood, she said it out real loud to her coworker, and everybody, even the patient sitting in chairs, make sure you get something, this guy has HIV.”

Social stigma

The most in-depth parts of conversation within the semi-structured interviews entailed beliefs regarding HIV and HIV care by SSP participants. Specifically, they described fears of being judged and rejected by the societal community, embarrassment, and feeling alone in their journey with HIV. The fear of judgment was also described as being a hindrance to their retention in HIV care. Participants reported feeling lonely in their care continuum and withdrawn from those who did not know their status. They also reported being fearful that medical professionals would treat them differently because of their HIV status. Below are sample quotations:

“I was worried about people judging me, people knowin’ my business, my personal business getting out, my personal health information getting out on the streets, you know?”

“Well, I have HIV. It’s like you risk outing yourself and putting yourself out there for people to reject you.”

“There’s a fear that everyone will find out about my HIV status and leave.”

Along with personal feelings of judgment and rejection, participants reported that their encounters with those around them were not always positive and cemented their fears of asking for help or strategy of avoiding others. Many participants reported negative encounters with other people, including medical professionals, friends, and family. These encounters took form as stereotyping, incorrect information regarding HIV, negative feelings, and perceptions of persons with HIV and/or associations with drug use. Most commonly, participants reported an over-generalized belief by those they encountered, specifically being labeled as homosexual or a person who uses drugs:

“People look at you—either you’re a homosexual or you’re an IV user—my brother was not. He just slept with the wrong person.”

“The stigma and the way everybody treated my brother before he died. I haven’t told a soul except my doctors because of that.”

“Some people I deal with, even my family, for instance. They were rude to me as far as calling me nasty or sick sometimes. Yeah, people are super cruel. It’s that they’re not educated about it. They’re just stupid, and they say harsh things.”

Physical barriers to care

Participants reported external barriers that prevented access to HIV care. Examples included lack of transportation, inaccessible location, and inflexible hours outside of working hours in a traditional clinic. Participants experiencing homelessness had many more difficulties initiating linkage to and maintaining care than those who were stably housed.

“Transportation makes it hard for me to get over and get my meds.”

“I was just gonna say that my only barrier when I’m not regularly on my medication and because I have a dope habit, is that a lot of time this is too far and it’s too hot for me to walk all the way over here. I still don’t have the energy to do it.”

“When I hadn’t got a phone, I couldn’t stay on top of it or contact people to get back into care. Then if you’re on the streets, and just really don't think of it.”

Positive experiences in the Syringe Exchange and Facilitators to HIV Care.

SSP as a protective factor staying in care

Participants reported several positive experiences within the SSP-based THR intervention that could facilitate retention in HIV care. All participants had positive remarks regarding the use of THR for HIV care. All participants were accepting of the use of THR for HIV care and utilizing a tele-health modality for services. All participants agreed it would be beneficial for the community to continue to offer this service. SSP participants reported their confidence in HIV screening and counseling services and felt inclined to share this resource with others.

“And probably one of the best resources or means of getting HIV care.”

“I think that it’s basic—you come here to get syringes because you need to use. Then, of course, they help with HIV. Because you use syringes, you—there’s a possible risk that you can get it, or- and it’s all one place, one-stop shop.”

Staying in care: encouragement from peers and clinicians at the SSP

Participants were asked if the SSP-based THR intervention was a desired venue for HIV care. All participants reported positive comments regarding their experience with the SSP. Many also cited positive attributes of the personalities of staff that should be emulated among traditional health care provider staff. Although many reported general mistrust with medical professionals, participants considered SSP clinicians trustworthy. Participants described the positivity and welcomeness they felt when visiting the physician at the SSP. Participants reported the unique attributes of staff needed to work with people with HIV and/or PWID. Participants appreciated that the SSP is in an area home to a community placed at high risk, such as PWID and those experiencing homelessness. Participants endorsed the necessity of the SSP and its services for HIV care. Lastly, confidentiality was noted throughout the participant transcripts as being very important when working with patients with HIV:

“The people that are here are very familiar and supportive of people with HIV and other diseases like hepatitis, and things like that. They don’t treat us differently.”

“As far as care, the people here—the caseworkers and everyone—they’re very supportive about it and they try their best to do the most they can to get it to me over and over and over again.”

“Just to let someone know that, if you’re open and honest with me, I’m not going to judge you. I’m still going to give you the best care, something like that to help the person understand that they’re not asking you these questions to judge you or shut you out. They're just trying to help you the best way they can.”

“I think the best thing is to have someone who does a lot more listening than talking, someone that doesn’t appear to be nosy or prying. Because just like in life in general I feel confidentiality is important.”

Discussion

In this study, we explored the perspectives of PWID with HIV regarding a novel intervention of telehealth-enhanced HIV care delivered through an SSP leveraging the expertise of peer harm reduction counselors (Tele-Harm Reduction). Consistent with previous studies, many of these participants reported stigma and discrimination in traditional healthcare settings as the main reasons they discontinued their HIV care or did not seek HIV care. Notable strengths of the THR model that facilitated HIV linkage and retention included: (1) nonjudgmental staff, including those with lived experience, who collaborated closely with participants for their HIV and addiction care, and (2) wraparound services in conjunction with telehealth visits that supported comprehensive care at one venue.

Telehealth has been proven to be feasible, cost-effective, and sustainable in SSP settings [35]. Telehealth also reduced the amount of time between an individual’s interest in treatment and getting into treatment and speaking to a provider. This shortening of time provides improved rates in substance use treatment, engagement, and retention [35, 36]. SSPs are often one of the few health-related resources with which PWID regularly engage and therefore fill a unique role in promoting health in a welcoming and non-stigmatizing way [37]. Existing literature reveals that social stigma strongly influences PWID’s healthcare system engagement [38]. Telehealth has been used for direct patient consultation for HIV care, with marginalized populations such as people with HIV in the prison system, and in remote geographical locations [39,40,41]. The research on the effectiveness of SSPs in reducing injection risk behaviors and HIV transmission dates to 1989 [42]. SSPs that have trust building communication with PWID can reduce and maintain low levels of HIV transmission [43] and further, it has been found that peers reach more diverse networks of PWID [42].

This qualitative assessment of facilitators and barriers to HIV care among PWID frequenting services at an SSP reveal that low-barrier access to compassionate medical care through telehealth could facilitate access to care for a traditionally overlooked cohort. Tookes et al. 2021 [22] reported out of the 35 PWID living with HIV enrolled in the Tele-Harm Reduction intervention, 25 (78%) were virally suppressed at 6 months. A harm reduction framework was employed afterwards to provide on demand access to HIV care among the PWID via remote technology. This telehealth model was integrated to the fixed and mobile site or the location of the patient’s choosing [22]. Centering on PWID, the engagement of peers and linkage to care coordinators in this intervention was of utmost importance. Our study shows that respondent PWID reported their engagement in treatment was influenced by the warm demeanor and non-judgmental ways of staff workers at the IDEA exchange. The majority of those interviewed reported on the stigmatization that they endured in the traditional healthcare setting which ultimately affected their care and treatment, a barrier that could be overcome by the Tele-Harm Reduction intervention.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Results may not be generalizable since it was conducted at a single SSP in a single city. Additionally, this secondary analysis of transcripts is limited in scope since the qualitative interviews were done during the implementation of THR and the interview guide was not refined in pursuit of the goals of this analysis in identification of barriers and facilitators. Finally, only one interviewer conducted the interviews, which can introduce interview bias, where the interviewer may subconsciously influence the response of the interviewee. Nonetheless, interviews were conducted within the trusted SSP setting and likely had limited social desirability bias in this context.

Next steps

This qualitative study elucidated the experience of PWID and their perspective on the importance of destigmatizing provision of HIV care. Due to the promise of the THR intervention, it is currently being tested in a multi-site efficacy trial [44] aiming to transform the way PWID access comprehensive HIV care.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

HIV among people who inject drugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 28, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/hiv-idu.html.

Arum C, Fraser H, Artenie AA, Bivegete S, Trickey A, Alary M, Astemborski J, et al. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(21)00013-x.

Chueng TA, Tookes HE, McLaughlin M, Arcaro-Vinas AM, Serota DP, Bartholomew TS. Injection and sexual behavior profiles among people who inject drugs in Miami, Florida. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(9):1374–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2022.2083171.

Glick JL, Lim S, Beckham SW, Tomko C, Park JN, Sherman SG. Structural vulnerabilities and HIV risk among sexual minority female sex workers (SM-Fsw) by identity and behavior in Baltimore, MD. Harm Reduct J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00383-2.

Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2019;33(9):1411–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000002227.

Bunda BA, Bassett IV. Reaching the second 90. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019;14(6):494–502. https://doi.org/10.1097/coh.0000000000000579.

Idrisov B, Lunze K, Cheng DM, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Quinn E, Bridden C, et al. Role of substance use in HIV care cascade outcomes among people who inject drugs in Russia. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-017-0098-5.

Lindsay BR, Mwango L, Toeque M-G, Malupande SL, Nkhuwa E, Moonga CN, Chilambe A, et al. Peer community health workers improve HIV testing and art linkage among key populations in Zambia: retrospective observational results from the Z-check project, 2019–2020. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.26030.

Yehia BR, Rebeiro P, Althoff KN, Agwu AL, Horberg MA, Samji H, Napravnik S, et al. Impact of age on retention in care and viral suppression. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000000489.

Surratt HL, Yeager HJ, Adu A, González EA, Nelson EO, Walker T. Pre-exposure prophylaxis barriers, facilitators and unmet need among rural people who inject drugs: a qualitative examination of syringe service program client perspectives. Front Psychiatry. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.905314.

Hall BJ, Sou K-L, Beanland R, Lacky M, Tso LS, Ma Q, Doherty M, Tucker JD. Barriers and facilitators to interventions improving retention in HIV care: a qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2016;21(6):1755–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1537-0.

Do M, Ho HT, Dinh HT, Le HH, Truong TQ, Dang TV, Nguyen DD, Andrinopoulos K. Intersecting stigmas among HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Vietnam. Health Serv Insights. 2021;14:117863292110135. https://doi.org/10.1177/11786329211013552.

Smith DJ, Combellick J, Jordan AE, Hagan H. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease progression in people who inject drugs (PWID): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):911–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.004.

SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35319/2020NSDUHFFR102121.htm. Accessed 20 Apr 2023

Madi D, Bhaskaran U, Ramapuram JT, Rao S, Mahalingam S, Achappa B. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(3):220. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.109196.

McKnight C, Shumway M, Masson CL, Pouget ER, Jordan AE, Des Jarlais DC, Sorensen JL, Perlman DC. Perceived discrimination among racial and ethnic minority drug users and the association with health care utilization. NYU Scholars. Routledge, October 2, 2017. https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/perceived-discrimination-among-racial-and-ethnic-minority-drug-us.

McNeil R, Kerr T, Coleman B, Maher L, Milloy MJ, Small W. Antiretroviral therapy interruption among HIV positive people who use drugs in a setting with a community-wide HIV treatment-as-prevention initiative. AIDS Behav. 2016;21(2):402–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1470-2.

Karch DL, Gray KM, Shi J, Hall HI. HIV infection care and viral suppression among people who inject drugs, 28 U.S. jurisdictions, 2012–2013. Open AIDS J. 2016;10(1):127–35. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601610010127.

Kim N, Welty S, Reza T, Sears D, McFarland W, Raymond HF. Undiagnosed and untreated HIV infection among persons who inject drugs: results of three national HIV behavioral surveillance surveys, San Francisco, 2009–2015. AIDS Behav. 2018;23(6):1586–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2284-1.

Goedel WC, King MR, Lurie MN, Galea S, Townsend JP, Galvani AP, Friedman SR, Marshall BD. Implementation of syringe services programs to prevent rapid human immunodeficiency virus transmission in rural counties in the United States: a modeling study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;70(6):1096–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz321.

Bartholomew TS, Onugha J, Bullock C, Scaramutti C, Patel H, Forrest DW, Feaster DJ, Tookes HE. Baseline prevalence and correlates of HIV and HCV infection among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program; Miami, FL. Harm Reduct J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00385-0.

Tookes HE, Bartholomew TS, Suarez E, Ekowo E, Ginoza M, Forrest DW, Serota DP, et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and pilot results of the tele-harm reduction intervention for rapid initiation of antiretrovirals among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;229:109124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109124.

Reddon H, Marshall BD, Milloy M-J. Elimination of HIV transmission through novel and established prevention strategies among people who inject drugs. Lancet HIV. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30292-3.

Sypsa V, Psichogiou M, Paraskevis D, Nikolopoulos G, Tsiara C, Paraskeva D, Micha K, et al. Rapid decline of HIV incidence among people who inject drugs during a fast-track combination prevention programme following an HIV outbreak in Athens. J Infect Dis. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix100.

Scannell C. Voices of hope: substance use peer support in a system of care. Subst Abuse Res Treat. 2021;15:117822182110503. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218211050360.

Eddie D, Hoffman L, Vilsaint C, Abry A, Bergman B, Hoeppner B, Weinstein C, Kelly JF. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: a systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Front Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052.

Boshara AI, Patton ME, Hunt BR, Glick N, Johnson AK. Supporting retention in HIV care: comparing in-person and telehealth visits in a Chicago-based infectious disease clinic. AIDS and Behavior. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35113267/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Rodriguez AE, Wawrzyniak AJ, Tookes HE, Vidal MG, Soni M, Nwanyanwu R, Goldberg D, et al. Implementation of an immediate HIV treatment initiation program in a Public/Academic Medical Center in the US South: the Miami test and treat rapid response program. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(13):287–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02655-w.

Volume 33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/index.html.

SB 366 Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA), Sess. (Florida, 2019) (enacted). www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2019/366

Tookes H, Bartholomew TS, St. Onge JE, Ford H. The University of Miami Infectious Disease Elimination Act syringe services program: a blueprint for student advocacy, education, and innovation. Acad Med. 2020;96(2):213–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003557.

Tookes H, Bartholomew TS, Geary S, Matthias J, Poschman K, Blackmore C, Philip C, et al. Rapid identification and investigation of an HIV risk network among people who inject drugs—Miami, FL, 2018—AIDS and behavior. SpringerLink. Springer US, September 25, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02680-9

A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data .... https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748. Accessed 21 Apr 2023.

Tong J, Sainsbury A, Craig P. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17872937/. Accessed n.d.

Watson DP, Swartz JA, Robison-Taylor L, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Erwin K, Gastala N, Jimenez AD, Staton MD, Messmer S. Syringe service program-based telemedicine linkage to opioid use disorder treatment: protocol for the stamina randomized control trial. BMC Public Health. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33789642/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Dennis JV, Ingram ML, Burks PW, Rachal ME. Effectiveness of streamlined admissions to methadone treatment: a simplified time-series analysis. J Psychoact Drugs. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7931865/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Wenger LD, Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Morris T, Ongais L, Lambdin BH. Ingenuity and resiliency of syringe service programs on the front lines of the opioid overdose and COVID-19 crises. Transl Res J Lab Clin Med. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33746108/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Muncan DC, Walters B, Ezell SM, Ompad J. ‘They Look at Us like Junkies’: influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm Reduct J. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32736624/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Wood BR, Unruh KT, Martinez-Paz N, Annese M, Ramers CB, Harrington RD, Dhanireddy S, Kimmerly L, Scott JD, Spach DH. Impact of a telehealth program that delivers remote consultation and longitudinal mentorship to community HIV providers. Open Forum Infect Dis. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27703991/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Young JD, Patel M, Badowski M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Vaughn P, Shicker L, Puisis M, Ouellet LJ. Improved virologic suppression with HIV subspecialty care in a large prison system using telemedicine: an observational study with historical controls. Clin Infect Dis. U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 1, 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4305134/.

Ohl M, Dillon D, Moeckli J, Ono S, Waterbury N, Sissel J, Yin J, Neil B, Wakefield B, Kaboli P. Mixed-methods evaluation of a telehealth collaborative care program for persons with HIV infection in a rural setting. J Gen Intern Med. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23475640/. Accessed 20 Apr 2023.

Broz D, Carnes N, Chapin-Bardales J, Des Jarlais DC, Handaganic S, Jones CM, McClung RP, Asher AK. Syringe services programs' role in ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S.: why we cannot do it without them. Am J Prev Med. Elsevier, October 19, 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379721003895.

Des Jarlais DC, Hagan H, Friedman SR, Friedmann P, Goldberg D, Frischer M, Green S, et al. Maintaining low HIV seroprevalence in populations of injecting drug users. Albert Einstein College of Medicine. American Medical Association, October 18, 1995. https://einstein.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/maintaining-low-hiv-seroprevalence-in-populations-of-injecting-dr-2.

Tookes HE, Oxner A, Serota DP, Alonso E, Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Ucha J, et al. Project T-sharp: study protocol for a multi-site randomized controlled trial of tele-harm reduction for people with HIV who inject drugs—trials. BioMed Central. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-023-07074-w.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Drug abuse (NIDA) under the Grant Number DP2DA053720. The content is solely responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., B.H., Y.R., and T.C. wrote the main manuscript and prepared figures. All authors reviewed and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. H.T. oversaw all steps of the manuscript as PI and mentor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Scaramutti, C., Hervera, B., Rivera, Y. et al. Improving access to HIV care among people who inject drugs through tele-harm reduction: a qualitative analysis of perceived discrimination and stigma. Harm Reduct J 21, 50 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00961-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00961-8