Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection prevalence is particularly high in people who inject drugs (PWID), a population that faces many barriers to HCV testing and care. A better understanding of the determinants of access to HCV testing is needed to improve their engagement in the HCV care cascade. We used data from a cross-sectional survey of people who inject drugs, mainly opioids, to identify factors associated with recent HCV testing.

Methods

Self-reported data on HCV antibody testing were analyzed for 550 of the 557 PWID enrolled in PrebupIV, a French cross-sectional community-based survey which assessed PWID acceptability of injectable buprenorphine as a treatment. Factors associated with recent (i.e., in the previous six months) HCV antibody testing were identified performing multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Among the study sample, 79% were men and 31% reported recent HCV antibody testing. Multivariable analysis found that PWID who did not disclose their injection practices to anyone (aOR [95% CI] 0.31 [0.12,0.82], p = 0.018), older PWID (aOR [95% CI] 0.97 [0.95,1.00], p = 0.030) and employed respondents (aOR [95% CI] 0.58 [0.37,0.92], p = 0.019) were all less likely to report recent HCV testing. No association was found between opioid agonist therapy and HCV testing.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that non-disclosure of injection practices, employment and age were all barriers to HCV antibody testing. Preventing stigma around injection practices, developing the HCV testing offer in primary care and addiction care services, and training healthcare providers in HCV care management could improve HCV testing and therefore, the HCV care cascade in PWID.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In people who inject drugs (PWID), hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission mainly occurs through the sharing of contaminated injection materials [1]. In Western Europe, estimated HCV seroprevalence in PWID was 53.2% in 2017, accounting for approximately 537,000 individuals [2]. HCV prevalence in PWID in France ranges from 48 to 64% [3, 4], depending on the sample; this is considerably higher than the estimated 1% in the French general population [5]. Micro-elimination is a nested strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO) hepatitis C elimination plan [6] which aims to eliminate HCV epidemic by 2030 (90% and 65% reduction in incidence and mortality, respectively). France has planned to reach this goal by 2025 [7].

Despite the high prevalence of HCV in PWID in France, testing is insufficient. Consequently, a large proportion of PWID with the disease are undiagnosed [8,9,10]. A recent French study conducted in harm reduction services suggested that 8% of PWID who had injected at least once during their lifetime had never been tested for HCV. That study also suggested that only half of HCV antibody-negative (52%) people who use drugs [11] had been tested during the previous six months as per official recommendations in France [12]. Testing is a key stage in the HCV care cascade; increasing testing in terms of the number of people tested and the frequency can result in prompt HCV cure, a lower risk of transmission to other PWID, and a lower HCV-related morbidity burden [13].

Although direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for HCV have led to considerably greater access to care for HCV-infected individuals, a substantial proportion of PWID do not yet benefit from this recent treatment. Furthermore, PWID face many barriers to HCV testing and care access at the individual, provider and health system levels. At the individual level, barriers include poor social conditions (unstable housing, lack of health insurance) and limited knowledge about HCV infection [14,15,16]. At the provider level, stigma and discrimination around drug injection play a large role in PWID underuse of available healthcare services [17,18,19]—including HCV testing [20]—and poor engagement in care [21]. Barriers at the health system level include limited geographical and financial accessibility to testing and criminalization of drug use [14, 15, 19, 22, 23]. For example, although integrated care could help to optimize the care cascade for PWID [12], onsite RNA testing or treatment are not systematically available in harm reduction or addiction care services in France [24]. In the context of simplifying HCV management, non-specialist primary care provider involvement [25], the HCV testing offer, and treatment uptake in prison settings [26] should all be reinforced. While certain health system barriers for PWID have been successfully tackled in recent years [12], many individual and provider-level barriers persist. These need to be explored in greater detail in order to better identify strategies to engage PWID in the HCV care cascade.

In this context, we used the PrebupIV study to identify factors associated with recent HCV antibody testing (i.e., during the previous six months) in PWID, mainly opioids, living in France.

Methods

Study design

PrebupIV is a cross-sectional community-based survey conducted between May and August 2015 in France in collaboration with the association AIDES and with the support of other associations (Psychoactif, Fédération Addiction, ASUD, Médecins du Monde). It aimed to assess PWID acceptability of intravenous buprenorphine as a treatment. The survey is described in detail elsewhere [27].

Eligibility criteria were as follows: 18 years of age or older, French speaking and having injected opioids in the previous week. The survey questionnaire was administered face to face by field workers in harm reduction services or was self-administered online using a web link available on Psychoactif.org. The contents of the questionnaire did not differ between the questionnaire types (i.e., face-to-face versus online). The questionnaire collected self-reported data about sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral and health data, drug use practices, and access to HCV testing. A total of 557 PWID completed the questionnaire. No reimbursement was provided for participation. The survey was authorized by the national French Data Protection Authority [Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL)] (approval number 1812588v0–05/12/2014). The protocol was designed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and all participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion.

Study sample

For the present study, we selected 550 PWID among PrebupIV’s 557 participants. People without data on history of HCV testing (n = 7) (Fig. 1) were excluded.

Variables

The main outcome ‘recent HCV testing’ was created as a dichotomous variable by identifying participants who reported testing for HCV in the previous six months, and those tested either more than six months previously or never tested. People who answered “Do not know” were classified in the latter group. This variable was created in accordance with current French recommendations on HCV testing frequency for at-risk populations [12]. At the time of the study, only HCV antibody testing was available in harm reduction services; RNA testing was not available.

Independent variables were sociodemographic data (age, gender, unstable housing, employment), behavioral and health data [experience of recent incarceration, taking opioid agonist therapy (OAT)] and drug use practices (most frequently injected opioid, other injected substances, time since first injection of opioids, drug injection during the previous month, sharing of injecting equipment).

The variable ‘unstable housing’ included people living in a squat, or a caravan and those who reported being homeless (‘yes’ vs. ‘no’). The variable ‘recent incarceration’ included people who were incarcerated in the previous two years. The variable ‘currently on OAT’ reflected people who declared taking a prescribed OAT (buprenorphine, methadone, morphine sulfate) during the previous month; OAT was always prescribed in oral form. The variable ‘most frequently injected opioid’ was created considering the number of days of injection per month. The dichotomous variable ‘disclosure of injection practices’ comprised two categories: not having disclosed to anyone and having disclosed to someone, irrespective of whether this was a healthcare provider (e.g., addiction specialist, other specialist physician, nurse, general practitioner, pharmacist, harm reduction service worker) or other person (e.g., family, friend, internet forum).

Statistical analyses

We described and compared participants recently tested with those who were not, using a Chi-square and Wilcoxon test for categorical and continuous data, respectively.

To identify factors associated with recent HCV testing, we first performed univariable logistic regressions to identify eligible variables for the multivariable model at a threshold p value < 0.20. We then performed multivariable logistic regression using a backward stepwise procedure. Only variables with a p value < 0.05 were retained in the final model. The latter was adjusted for the type of questionnaire to take into account differences between people recruited in harm reduction services and those recruited online (Psychoactif.org). All statistical analyses were performed with Stata SE 14.2 software (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Descriptive analysis of the study sample

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the 550 PWID in PrebupIV selected for the analyses.

One third (31.3%) reported recent (i.e., in the previous six months) HCV testing, while 68.7% did not (i.e., tested more than six months previously or never tested).

Eighty (81.3%) percent were men and 18.7% women. Median age was 34 years [interquartile range (IQR): 28–41]. Twenty-two percent had unstable housing and 69% were unemployed. Thirteen percent reported recent incarceration (i.e., in the previous two years).

Buprenorphine was the opioid injected most frequently (46.2%), followed by heroin (17.1%) and morphine (15.3%). Over half (55.5%) the study sample reported injecting substances other than opioids (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines). Median time since first injection of opioids was seven years (IQR: 3–11). Seventy percent were currently on OAT and 17.1% reported sharing injection equipment. Nine percent had never disclosed their injection practices to anyone.

PWID recently tested for HCV were more likely to have answered the face-to-face questionnaire, to be unemployed, to have unstable housing, to be recently incarcerated, and to have talked with someone about their injection practices.

Factors associated with HCV testing in the study sample

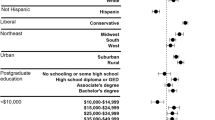

Table 2 presents the results of the univariable and multivariable regression analyses.

Univariable analyses showed that participants who answered the face-to-face questionnaire were more likely to have been recently tested for HCV (odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (95% CI)] 1.84 [1.20,2.83], p = 0.005). They also highlighted a significant association between recent HCV testing and some sociodemographic characteristics. Employed PWID were less likely to have been recently tested for HCV than those who were unemployed (OR [95% CI] 0.50 [0.33,0.78], p = 0.002). Unstable housing (OR [95% CI] 1.60 [1.06,2.43], p = 0.027) and recent incarceration (OR [95% CI] 1.84 [1.10,3.06], p = 0.019) were associated with a greater likelihood of recent HCV testing. PWID who had not disclosed their injection practices to anyone were less likely to have been recently tested (OR [95% CI] 0.23 [0.09,0.59], p = 0.002) than those who had disclosed them. No association was found between being on OAT and recent testing for HCV.

In the multivariable analysis, after adjusting for the type of questionnaire (face-to-face versus online), older (aOR [95% CI] 0.97 [0.95,1.00], p = 0.030) and employed (aOR [95% CI] 0.58 [0.37,0.92], p = 0.019) PWID were less likely to have been recently tested for HCV. PWID who had not disclosed their injection practices to anyone were also less likely to have been recently tested (aOR [95% CI] 0.31 [0.12,0.82], p = 0.018) than those who had disclosed them.

Discussion

The main finding from our analyses is that the non-disclosure of injection practices—whether to a healthcare professional or other person—was associated with less HCV testing in our study sample of PWID. This suggests that a taboo surrounding drug injection exists and that this taboo limits health promotion and PWID empowerment. The literature highlights that previous negative experiences with healthcare providers and the fear of being stigmatized or being treated poorly by them are huge barriers to testing and treatment for PWID [14, 15, 19]. Current and former PWID adopt strategies to avoid stigma and discrimination, including delaying healthcare as much as possible and not disclosing their drug use [28, 29]. In terms of HCV, this can lead to delayed testing and diagnosis as well as unwillingness to seek healthcare once diagnosed [20, 30]. A non-judgmental trustful healthcare provider-PWID relationship can facilitate HCV testing uptake [15, 30]. However, some healthcare providers feel that they do not have enough training to adequately consult PWID [31] or to manage HCV care for them (i.e., testing, diagnosis, liver disease assessment, treatment) [32]. Improved training of healthcare providers could change their representations and stereotypes of PWID. This could reduce stigma and discrimination and consequently improve the provider-patient relationship.

Employed PWID and older PWID were less likely to have been recently tested for HCV in our study. This suggests that employed PWID may not attend harm reduction services (where HCV testing is part of routine practice), a hypothesis supported by data from another study indicating that French harm reduction services mostly receive individuals living in social precarity [11]. Employed PWID probably attended primary care services more frequently, a setting where HCV testing is not routinely proposed. With regard to older PWID, our findings contradict previous French data which suggested that PWID under 25 years old was less frequently tested for HCV in harm reduction services than older persons [11]. One explanation for this contradiction may be that there was a lower prevalence of risk practices in older PWID in our study [33]. Another is that older PWID may have a more stable socioeconomic situation, which could translate into less use of harm reduction services in favor of primary care.

Moreover, participants in our study sample who answered the face-to-face questionnaire (i.e., recruited in harm reduction services) were more likely to have been recently tested for HCV. This is not surprising given that access to HCV testing is routine practice in these services (unlike in primary care).

Indeed, since 2016, the ‘targeted testing strategy’ has been recommended in France for people at risk of HCV contamination. Point-of-care (POC) testing strategies are also encouraged to facilitate access to HCV testing for marginalized PWID who do not attend healthcare facilities (primary care, hospitals, etc.) and for PWID who attend harm reduction services or primary care services but are at high risk of HCV infection [34].

In this context, innovative testing practices should be considered, such as point-of-care (POC) HCV RNA testing, in order to improve access to HCV testing for PWID who attend harm reduction centers and POC HCV antibody testing for those attending primary care services. A recent meta-analysis found that the use of onsite POC RNA viral load had a positive impact on reduced turnaround times between HCV antibody testing and treatment initiation, and on testing and treatment uptake for PWID, especially when it was proposed at the same visit and on the same day [35]. In France, a recent study demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of a ‘test and treat’ strategy based on dedicated screening days, proposing both HCV antibody and RNA testing in addiction care centers [36]. More generally, combining ‘test and treat’ strategies, linkage to care and early treatment initiation, would be a cost-effective option for reducing HCV incidence and improving PWID life expectancy in the French context [37]. POC antibody and RNA testing should be proposed in primary care settings, particularly for people at risk of HCV infection, as primary care providers can initiate HCV treatment in the context of simplified HCV management.

Finally, unlike other studies, our results did not find any association between OAT receipt and recent testing for HCV [38,39,40]. A recent French study found that access to HCV treatment for people with opioid use disorders was proportional to the number of hepatologists and gastroenterologists in an area [41]. This would suggest a lack of involvement of primary care providers or addiction physicians in the HCV cascade of care. Previous studies in contexts outside France where primary care physicians are more involved in HCV care, suggested that primary care represented an excellent opportunity for HCV testing for PWID [15, 39] and that OAT receipt was associated with a greater likelihood of having been tested [40, 42]. These results highlight the importance of proposing testing in settings where OAT is prescribed. The training of primary care providers should be fostered and specialized centers for addiction care promoted, especially given that DAAs can be initiated in both these medical settings, thanks to the recent (2019) simplification of HCV management in France which permits primary care providers to prescribe and manage DAA-based HCV treatment [43]. Reinforcing cooperation between specialists and primary care providers could also be a lever to improve the HCV care cascade for PWID.

The PrebupIV study highlighted very good acceptability by PWID of an injectable treatment for opioid use disorder [27]. Developing such a treatment in France could empower PWID to talk more about their injection practices. In turn, this could help healthcare providers to identify at-risk practices and consequently offer HCV testing.

A primary care network called ‘microstructures’ has been in place for several years in France. It provides tailored primary care to people who use drugs characterized by psychosocial vulnerabilities [44, 45]. These medical microstructures, which are less stigmatizing than harm reduction services, may be more adapted for PWID who do not attend harm reduction services. Developing this offer and making it more visible for PWID could improve HCV testing uptake and therefore the HCV cascade of care. Further studies are needed to confirm these possibilities.

The present study has limitations. First, responses to the questionnaires were self-reported leading to possible social desirability bias. However, the validity and reliability of self-reports in terms of drug use among PWID were previously demonstrated in a literature review. It analyzed studies which assessed these two dimensions using test–retest methods or comparisons of urinalysis results, respectively [46]. Second, the study’s cross-sectional design and lack of randomization means that the study sample may not be representative of all French PWID. However, people who inject opioids represent the majority of PWID [11]. Third, women were under-represented in our sample (20%). Finally, the study was conducted in 2015 before universal access to DAAs; the French context may have changed since then. Having said that, access to HCV testing is still very much a multi-dimensional issue today for PWID [47], especially healthcare providers’ stigmatization of this population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in our study sample of PWID, non-disclosure of injection practices constituted a barrier to accessing HCV testing; this barrier may be influenced by healthcare providers’ behaviors. Employment and age were also individual barriers to HCV testing and should be taken into consideration when investigating access to HCV testing in this population. No association was found between being on OAT and HCV testing. Removing the stigma surrounding injection practices, developing a HCV testing offers in routine primary care and addiction care services, and training healthcare providers in HCV care management are all actions which could enhance HCV testing in PWID and so improve their HCV care cascade.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. IA had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Change history

10 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00848-0

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- DAAs:

-

Direct-acting antiviral agents

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OAT:

-

Opioid agonist therapy

- POC testing:

-

Point-of-care testing

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

References

Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Stanaway J, Larney S, Alexander LT, Hickman M, et al. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to injecting drug use as a risk factor for HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1385–98.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1192–207.

Weill-Barillet L, Pillonel J, Semaille C, Léon L, Le Strat Y, Pascal X, et al. Hepatitis C virus and HIV seroprevalences, sociodemographic characteristics, behaviors and access to syringes among drug users, a comparison of geographical areas in France, ANRS-Coquelicot 2011 survey. Rev d’Épidémiol Santé Publique. 2016;64(4):301–12.

Grebely J, Larney S, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Hickman M, et al. Global, regional, and country-level estimates of hepatitis C infection among people who have recently injected drugs. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2019;114(1):150–66.

Pioche C. Estimation de la prévalence de l’hépatite C en population générale, France métropolitaine, 2011. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2016;13–14:224–9.

World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016–2021. 2016. p. 52. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246177/1/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?ua=1.

Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. La stratégie nationale de santé 2018–2022; 2017. p. 104.

Day E, Hellard M, Treloar C, Bruneau J, Martin NK, Øvrehus A, et al. Hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: challenges and recommendations for action within a health systems framework. Liver Int Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2019;39(1):20–30.

Grebely J, Bruneau J, Lazarus JV, Dalgard O, Bruggmann P, Treloar C, et al. Research priorities to achieve universal access to hepatitis C prevention, management and direct-acting antiviral treatment among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:51–60.

Lazarus JV, Sperle I, Spina A, Rockstroh JK. Are the testing needs of key European populations affected by hepatitis B and hepatitis C being addressed? A scoping review of testing studies in Europe. Croat Med J. 2016;57(5):442–56.

Cadet-Taïrou A, Janssen É, Guilbaud F. Profils et pratiques des usagers reçus en CAARUD en 2019. Tendances. 2020;142:4.

Delile JM, de Ledinghen V, Jauffret-Roustide M, Roux P, Reiller B, Foucher J, et al. Hepatitis C virus prevention and care for drug injectors: the French approach. Hepatol Med Policy. 2018;3(1):7.

Cousien A, Tran VC, Deuffic-Burban S, Jauffret-Roustide M, Dhersin JS, Yazdanpanah Y. Hepatitis C treatment as prevention of viral transmission and liver-related morbidity in persons who inject drugs. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD). 2016;63(4):1090–101.

Dillon JF, Lazarus JV, Razavi HA. Urgent action to fight hepatitis C in people who inject drugs in Europe. Hepatol Med Policy. 2016;1:2.

Barocas JA, Brennan MB, Hull SJ, Stokes S, Fangman JJ, Westergaard RP. Barriers and facilitators of hepatitis C screening among people who inject drugs: a multi-city, mixed-methods study. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11:1.

Wright C, Cogger S, Hsieh K, Goutzamanis S, Hellard M, Higgs P. “I’m obviously not dying so it’s not something I need to sort out today”: considering hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antivirals. Infect Dis Health. 2019;24(2):58–66.

Ward KM, McCormick SD, Sulkowski M, Latkin C, Chander G, Falade-Nwulia O. Perceptions of network based recruitment for hepatitis C testing and treatment among persons who inject drugs: a qualitative exploration. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;88:103019.

Swan D, Long J, Carr O, Flanagan J, Irish H, Keating S, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C testing, management, and treatment among current and former injecting drug users: a qualitative exploration. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(12):753–62.

Harris M, Rhodes T. Hepatitis C treatment access and uptake for people who inject drugs: a review mapping the role of social factors. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:7.

Skeer MR, Ladin K, Wilkins LE, Landy DM, Stopka TJ. ‘Hep C’s like the common cold’: understanding barriers along the HCV care continuum among young people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:246–54.

Madden A, Hopwood M, Neale J, Treloar C. Beyond interferon side effects: what residual barriers exist to DAA hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs? PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0207226.

Litwin AH, Drolet M, Nwankwo C, Torrens M, Kastelic A, Walcher S, et al. Perceived barriers related to testing, management and treatment of HCV infection among physicians prescribing opioid agonist therapy: the C-SCOPE Study. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(9):1094–104.

Grebely J, Hajarizadeh B, Lazarus JV, Bruneau J, Treloar C. Elimination of hepatitis C virus infection among people who use drugs: ensuring equitable access to prevention, treatment, and care for all. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;72:1–10.

Maticic M, Pirnat Z, Leicht A, Zimmermann R, Windelinck T, Jauffret-Roustide M, et al. The civil society monitoring of hepatitis C response related to the WHO 2030 elimination goals in 35 European countries. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):89.

Pol S, Fouad F, Lemaitre M, Rodriguez I, Lada O, Rabiega P, et al. Impact of extending direct antiviral agents (DAA) availability in France: an observational cohort study (2015–2019) of data from French administrative healthcare databases (SNDS). Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanepe/article/PIIS2666-7762(21)00267-2/fulltext.

Goujard C, Ayachi L, Artières P, Celse M, Fischer H, Musso S, et al. Prévention, dépistage et traitement de l’hépatite C chez les personnes détenues en France. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2022;3–4:40–7.

Roux P, Rojas Castro D, Ndiaye K, Briand Madrid L, Laporte V, Mora M, et al. Willingness to receive intravenous buprenorphine treatment in opioid-dependent people refractory to oral opioid maintenance treatment: results from a community-based survey in France. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2017;12(1):46.

Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, Drainoni ML, Salhaney P, Edeza A, et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:80–6.

Harris M, Ward E, Gore C. Finding the undiagnosed: a qualitative exploration of hepatitis C diagnosis delay in the United Kingdom. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23(6):479–86.

Muncan B, Walters SM, Ezell J, Ompad DC. ‘They look at us like junkies’: influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):53.

Lang K, Nei J, Wright J, Dell C, Berenbaum S, El-Aneed A. Qualitative investigation of barriers to accessing care by people who inject drugs in Saskatoon, Canada: perspectives of service providers. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8:35.

Grebely J, Drolet M, Nwankwo C, Torrens M, Kastelic A, Walcher S, et al. Perceptions and self-reported competency related to testing, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among physicians prescribing opioid agonist treatment: the C-SCOPE study. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:29–38.

Horyniak D, Dietze P, Degenhardt L, Higgs P, McIlwraith F, Alati R, et al. The relationship between age and risky injecting behaviours among a sample of Australian people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):541–6.

Dhumeaux D. Prise en charge thérapeutique et suivi de l’ensemble des personnes infectées par le virus de l’hépatite C -Rapport de recommandations 2016 [Internet]. Paris: Sous l’égide de l’ANRS et du CNS et avec le concours de l’AFEF; 2016 [cited 2021 Jul 21] p. 106. (La Documentation française). http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/rapportspublics/164000667/index.shtml.

Trickey A, Fajardo E, Alemu D, Artenie AA, Easterbrook P. Impact of hepatitis C virus point-of-care RNA viral load testing compared with laboratory-based testing on uptake of RNA testing and treatment, and turnaround times: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(3):253–70.

Debette-Gratien M, François S, Chevalier C, Alain S, Carrier P, Rigaud C, et al. Towards hepatitis C elimination in France: Scanvir, an effective model to test and treat drug users on dedicated days. J Viral Hepat. 2023;00:1–7.

Cousien A, Tran VC, Deuffic-Burban S, Jauffret-Roustide M, Mabileau G, Dhersin JS, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting harm reduction and chronic hepatitis C cascade of care in people who inject drugs: the case of France. J Viral Hepat. 2018;10:1197.

Anagnostou O, Fotiou A, Kanavou E, Antaraki A, Terzidou M, Richardson C, et al. Factors associated with HCV test uptake in heroin users entering substitution treatment in Greece. HIV Med. 2018;19(Suppl 1):34–9.

Butler K, Day C, Sutherland R, van Buskirk J, Breen C, Burns L, et al. Hepatitis C testing in general practice settings: a cross-sectional study of people who inject drugs in Australia. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:102–6.

Grebely J, Tran L, Degenhardt L, Dowell-Day A, Santo T, Larney S, et al. Association between opioid agonist therapy and testing, treatment uptake, and treatment outcomes for hepatitis C infection among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2021;73(1):e107–18.

Marcellin F, Roux P, Lazarus JV, Rolland B, Carrieri P. France removes hepatitis C treatment prescriber restrictions—but what is the impact of the delay for key populations? Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2418–9.

Gibbs D, Price O, Grebely J, Larney S, Sutherland R, Read P, et al. Hepatitis C virus cascade of care among people who inject drugs in Australia: factors associated with testing and treatment in a universal healthcare system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:109050.

HAS. Hépatite C : prise en charge simplifiée chez l’adulte [Internet]. Haute Autorité de Santé. 2019. p. 4. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2911891/fr/hepatite-c-prise-en-charge-simplifiee-chez-l-adulte#voirAussi.

Di Nino F. Impact du travail en réseau de la médecine de ville. Réduction Risques Infect Chez Usagers Drogue INSERM « Expert Collect ». 2010;489–92.

Di Nino F, Imbs JL, Melenotte GH, Réseau RMS, Doffoel M. Dépistage et traitement des hépatites C par le réseau des microstructures médicales chez les usagers de drogues en Alsace, France, 2006–2007. Bull Épidémiol Hebd BEH. 2009;37:400–4.

Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(3):253–63 (discussion 267–268).

Day E, Broder T, Bruneau J, Cruse S, Dickie M, Fish S, et al. Priorities and recommended actions for how researchers, practitioners, policy makers, and the affected community can work together to improve access to hepatitis C care for people who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;66:87–93.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the PrebupIV Study Group and all the stakeholders involved, especially participating centers, their staff, and the study participants. We also thank the Public Health Doctoral Network of EHESP for funding Ilhame Anwar’s PhD. Finally, our thanks to Jude Sweeney (Milan, Italy) for the English revision and copyediting of our manuscript. The PrebupIV Study Group: P.Carrieri, P.Chappard, E.Choucair, M.Debrus, R. Delacroix, M.Dematteis, V.Dor_e, N. Joannard, V.Laporte, M.Mora, A.Morel, S.Morel, K.Ndiaye, F.Olivet, E.Pletschinger, D.Rojas-Castro, P.Roux, B.Spire, M.Suzan, G.Maradan, F. Vorspan. Participating centers and their staff: S.Longere (Marseille (Bus 31/32)); J.Levy (Marseille (Nouvelle Aube)); ASUD (Marseille); M.Debrus (Paris (Gaïa)); CAARUD AIDES: G.Penavayre (Pau), C.Labbe (Lille), R.Delacroix (Paris 02), T.Salaun (Rouen/Le Havre), S.Ngiema (Le Havre), D.Abouhari (Chartres), S.Le Friec (Brest), F.Crossouard (Rennes), V.Meignan (Laval), A.Celdran (La Roche-sur-Yon), J.Kubath (Bayonne), N.Fleuranceau-Rodier (Limoges), L.Baptiste (Niort), Y.Charrier (Angoulême), J.Lamant (La Rochelle), S.Coulmain (Poitiers), G.Collin (Clermont-Ferrand), C.De Froment (Toulouse), S.MC.Cormack (Béziers), C.Urdiales (Nîmes), T.Pivi (Nancy), A.Herter (Metz), JL.Ferry (Thionville), M.Daoud (Epinal), E.Bauer (Besançon), P.Skamba (Mulhouse), R.Taugourdeau (Nevers), L.Bernard (Avignon), LA.Parent (Toulon), E-Y.Lemonnier (Grenoble), E.Marty (Bourg en Bresse).

Funding

This study was funded in full by France’s Inter-ministerial Mission for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviors (Mission interministérielle de lutte contre les drogues et les conduites addictives (MILDECA)). The funder had no role in the study design, analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PR and PC were involved in the study concept, design and the acquisition of data. Statistical analyses and interpretation of data were performed by IA, PR, CD, CP and PC. IA was principally involved in the drafting of the manuscript with the contribution of PR and PC. All the authors critically revised the article for important intellectual content and gave final approval for submission for publication. All agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey was authorized by the national French Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL)) (approval number 1812588v0–05/12/2014). The survey protocol was designed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and all participants provided informed consent prior to their inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Anwar, I., Donadille, C., Protopopescu, C. et al. Non-disclosure of drug injection practices as a barrier to HCV testing: results from the PrebupIV community-based research study. Harm Reduct J 20, 98 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00841-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00841-7