Abstract

Stigma and other barriers limit harm reduction practice integration by clinicians within acute psychiatric settings. The objective of our study was to explore mental health clinician attitudes towards substance use and associations with clinical experience and education level. The Brief Substance Abuse Attitudes Survey was completed among a convenience sample of mental health clinicians in Vancouver, British Columbia. Five predefined attitude subgroups were evaluated. Respondents’ attitudes towards substance use were associated with level of education on questions from two (non-stereotyping [p = 0.012] and treatment optimism [p = 0.008]) subscales. In pairwise comparisons, postgraduate education was associated with more positive attitudes towards relapse risk (p = 0.004) when compared to diploma-educated respondents. No significant associations were observed between years of clinical experience and participant responses. Our findings highlight important aspects of clinician attitudes that could improve harm reduction education and integration into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

North America is currently in the midst of an unprecedented opioid epidemic. The number of opioid-related deaths is rising steadily across Canada, with the highest mortality rate occurring in British Columbia [1]. Many individuals with opioid use present with several comorbidities including co-occurring mental illness and polysubstance use [2]. These factors contribute to several cross-cutting health and social challenges, often limiting treatment initiation and increasing opioid-related harms [3]

Individuals with both psychiatric and substance use issues are at increased risk for drug-related death [4], especially following periods of abstinence and reduced tolerance, such as hospitalization [5]. Harm reduction interventions, such as take-home naloxone and supervised consumption sites, are important elements of care and are associated with a reduced risk of overdose death [6]. Despite a robust body of evidence supporting the public health benefit of harm reduction interventions [7], stigma and related barriers (e.g. discrimination, lack of knowledge) can limit their availability across the health system [8]. Existing research consistently reveals that health care professionals hold negative beliefs about people with substance use disorders [9], and these attitudes may worsen over time for dually diagnosed patients [10]. Unfortunately, these stigmatized perceptions, such as abuse of health system resources or failure to adhere to recommended care and treatment [11, 12], often contribute to inequitable and poor provision of care including reduced access to harm reduction resources [13]. For example, in acute psychiatric settings addiction-related stigma among clinicians has been associated with poor harm reduction integration [14, 15]. The acceptability of harm reduction approaches among clinicians is an important determinant of increased implementation of essential, evidence-based services to combat the ongoing opioid epidemic.

Given the disconnect between the scientific evidence for and the resistance to harm reduction among health care providers, it is critical to examine how clinician attitudes towards substance use influence the harm reduction best practices in psychiatric settings. The objective of our study was to explore mental health clinician attitudes towards substance use and associations with clinical experience and education level.

Methods

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey among a convenience sample (n = 71) of mental health clinicians (nurses, physicians and allied health) between May and June 2022 at a tertiary care hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia. Participants were recruited via email based on internal distribution lists and informed consent was obtained electronically. Eligible participants were employed fulltime, parttime or casual within the hospital and had at least one year of experience in an acute psychiatric setting. The survey included socio-demographic questions (gender, education, clinical experience) and the 25-item Brief Substance Abuse Attitudes Survey (BSAAS). The BSAAS [16] was derived from a 50-item instrument, the Substance Abuse Attitudes Survey, using a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to examine attitudes towards various aspects of drug and alcohol use and five predefined attitude subgroups were evaluated: permissiveness, non-stereotypes, treatment intervention, treatment optimism and non-moralism [17]. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine the association between attitudes towards substance use and years of clinical experience and education level. Hochberg procedure [18] was applied to adjust p values for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. Ethics approval was obtained from the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Review Board.

Results

Among the 71 respondents who completed the survey, the majority identified as female (85%), were employed as nurses (48%), with bachelor’s (44%) or master’s (23%) level education and fewer than ten years of experience in their primary clinical role (71%) (Table 1). Over half (60%) of respondents reported a high level of daily contact (> 71% of workload) with individuals who use substances, but low levels of comfort in providing care and treatment (Table 1).

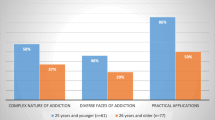

Respondents’ attitudes and views towards substance use were associated with level of education on questions from two subgroups, non-stereotyping (p = 0.012) and treatment optimism (p = 0.008) (Table 2). In pairwise comparisons within the treatment optimism subgroup, postgraduate education was associated with more positive attitudes towards relapse risk (p = 0.004) when compared to diploma-educated respondents. In contrast, no pairwise effect was observed between education type with respect to propensity for hard drug use (p = 0.310) within the non-stereotyping subgroup. No significant associations were demonstrated between years of clinical experience and attitudes towards substance use (Table 2).

Discussion

We found that postgraduate education contributes to less stereotyping attitudes and a higher level of treatment optimism when working with individuals with substance use or dependence. These findings highlight important dimensions of clinician attitudes (e.g. beliefs) that could improve harm reduction education and integration into clinical practice.

Prior research has identified that negative attitudes are consistently viewed as barriers to evidence-based harm reduction practices [19]. Even though combating stigma has been a focus of public health professionals, there are few interventions that demonstrate measurable improvements towards stigmatizing beliefs among health care providers [20]. Livingston and colleagues [21] in a systematic review identified that on-the-job education, which includes contact-based training, has demonstrated improvements in reducing stigma but the evidence base remains equivocal. Our results add to the literature by demonstrating a significant effect between less stigmatizing views and individuals with postgraduate education. This finding is important and may reflect the focus on anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive practices within postgraduate pedagogy which challenges personal values and social norms regarding substance use [22].

We observed no associations between years of experience and clinician attitudes in our sample. This nonsignificant finding was in contrast to our hypothesis and existing literature which suggests that more experience and therefore increased contact with individuals who use substances fosters more positive attitudes [23]; however, this effect appears to be stronger for the general public [24] than health care providers. Moreover, this null finding highlights opportunities to provide workplace education for clinicians across all stages of their career, regardless of experience level.

Further research is required to understand elements of education and training that are associated with more positive attitudes towards and improved care for individuals who use substances. The limitations of this study include a low proportion of non-nursing providers, generalizability to other regions or settings and the cross-sectional survey design with assessments of attitudes at a single time-point.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Coroners B. Illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC. Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General; 2022. p. 1–25. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf. Accessed 31 Dec 2022.

Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019;394(10208):1560–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32229-9.

Opioid-related harms in Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018. https://www.cihi.ca/en/opioid-related-harms-in-canada. Accessed 3 Dec 2022.

Fridell M, Bäckström M, Hesse M, Krantz P, Perrin S, Nyhlén A. Prediction of psychiatric comorbidity on premature death in a cohort of patients with substance use disorders: a 42-year follow-up. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2098-3.

Lewer D, Menezes D, Cornes M, et al. Hospital readmission among people experiencing homelessness in England: a cohort study of 2772 matched homeless and housed inpatients. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2021;75(7):681–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215204.

Hawk KF, Vaca FE, D’Onofrio G. Reducing fatal opioid overdose: prevention, treatment and harm reduction strategies. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(3):235–45.

Tran MTN, Luong QH. Community harm reduction initiatives: essential investments for illicit drug prevention and control in the future. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;18:100373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100373.

Aronowitz S, Meisel ZF. Addressing stigma to provide quality care to people who use drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146980. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46980.

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018.

Avery J, Han BH, Zerbo E, et al. Changes in psychiatry residents’ attitudes towards individuals with substance use disorders over the course of residency training. Am J Addict. 2017;26(1):75–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12406.

Henderson S, Stacey CL, Dohan D. Social stigma and the dilemmas of providing care to substance users in a safety-net emergency department. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1336–49. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0088.

Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):277–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600595053.

Knaak S, Christie R, Mercer S, Stuart H. Harm reduction, stigma and the problem of low compassion satisfaction. J Ment Health Addict Nurs. 2019;3(1):e8–21. https://doi.org/10.22374/jmhan.v3i1.37.

Howard V, Holmshaw J. Inpatient staff perceptions in providing care to individuals with co-occurring mental health problems and illicit substance use. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(10):862–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01620.x.

Khan GK, Harvey L, Johnson S, et al. Integration of a community-based harm reduction program into a safety net hospital: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00622-8.

Veach C. Physician attitudes in chemical dependency: The effects of personal experience and recovery. Subst Abuse. 1990;2(11):97–101.

Chappel JN, Veach TL, Krug RS. The substance abuse attitude survey: an instrument for measuring attitudes. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46(1):48–52. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1985.46.48.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x.

McGinty EE, Barry CL. Stigma reduction to combat the addiction crisis—developing an evidence base. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1291–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2000227.

Bielenberg J, Swisher G, Lembke A, Haug NA. A systematic review of stigma interventions for providers who treat patients with substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;131:108486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108486.

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review: Reducing substance use-related stigma. Addiction. 2011;107(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x.

Richmond I, Foster J. Negative attitudes towards people with co-morbid mental health and substance misuse problems: an investigation of mental health professionals. J Ment Health. 2003;12(4):393–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963823031000153439.

Kennedy-Hendricks A, McGinty EE, Summers A, Krenn S, Fingerhood MI, Barry CL. Effect of exposure to visual campaigns and narrative vignettes on addiction stigma among health care professionals. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146971. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46971.

Wild TC, Koziel J, Anderson-Baron J, et al. Public support for harm reduction: A population survey of Canadian adults. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0251860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251860.

Funding

Providence Health Care Knowledge Translation Grant. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. AR had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AR, MC, EJD and Kolar contributed to concept and design. AR, MG and JD acquired, analysed or interpreted data. AR drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MG contributed to statistical analysis. MC and EB provided administrative, technical or material support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Russolillo, A., Guan, M., Dogherty, E.J. et al. Attitudes towards people who use substances: a survey of mental health clinicians from an urban hospital in British Columbia. Harm Reduct J 20, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00733-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00733-w