Abstract

Background

Studies have suggested that the injection drug use (IDU) was no longer the main transmission route of HIV/AIDS in China. However, there has never been a study to assess the national HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs (PWIDs) based on a nationwide database.

Methods

PWIDs among new entrants in detoxification centers with HIV test results were extracted from the 2008–2016 National Dynamic Management and Control Database for Persons Who Use Drugs (NDMCD). Logistic regressions were used to analyze factors associated with HIV infection, and joinpoint regression were used to examine trends in the HIV prevalence.

Results

A total of 103,619 PWIDs among new entrants tested for HIV in detoxification centers between 2008 and 2016 were included in the analysis. The HIV prevalence was 5.0% (n = 5167) among PWIDs. A U-shaped curve of the HIV prevalence decreased from 4.9% in 2008 to 3.3% in 2010 (Annual Percent Change [APC] − 20.6, 95% CI − 32.5 to − 6.7, p < 0.05) and subsequently increased from 3.3% in 2010 to 8.6% in 2016 (APC 17.9, 95% CI 14.5–21.4, p < 0.05) was observed. The HIV prevalence in west regions in China all presented decreased trends, while central and eastern regions presented increased trends.

Conclusions

Although the HIV prevalence has been declining in general population, the HIV prevalence among PWIDs has shown an increasing trend since 2010. Current policies on HIV control in PWIDs should be reassessed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Injection drug use (IDU) is a leading cause of HIV infections because of sharing contaminated injection equipment [1]. Among persons who inject drugs (PWIDs), HIV could be transmitted through sexual contact and injection-related risk behavior, and injection-related transmission is thought to be the dominant route in most settings [2]. According to a recent study covering 99% of the population aged 15–64 years globally, the number of countries reported IDU has increased from 148 in 2008 to 179 in 2017 [3, 4]. Moreover, the global prevalence of HIV among PWIDs was 17.8% in 2017, and PWIDs were estimated to be 36 times more likely than those in the general population to be living with HIV [4, 5].

In China, the first reported 79 HIV cases among PWIDs were in Dehong, Yunnan Province in 1989 [6]. Prior to 2007, IDU were predominantly responsible for new HIV/AIDS infections [7, 8]. However, the proportion of new HIV infections through sexual transmission exceeded IDU and became the primary transmission route in 2007 [8, 9]. Several previous studies using surveillance data also indicated that the national HIV prevalence among PWIDs has decreased slightly from 10.6% in 2002 to 9.1% in 2010 [10, 11]. Lan Wang et al. found that trends in the HIV prevalence in China peaked at 30.3% among PWIDs in 1999, and then gradually decreased to 10.9% in 2011 [12]. Correspondingly, the needle sharing behavior among PWIDs has decreased from 19.5% in 2006 to 11.3% in 2011 [12]. This was made possible by the inclusion of harm reduction strategies, such as opioid substitution treatment (OST) and needle and syringe programs (NSPs) [12]. Lei Zhang et al. systematically analyzed trends in the HIV prevalence by regions and subpopulation groups from 1995 to 2010, and found the prevalence of HIV infection among PWIDs has been decreasing in all regions except for southwest China and has stabilized at a high level in northwest China [13].

National Dynamic Management and Control Database (NDMCD) is a national registry database set up by China government to register persons who use drugs (PWUDs), and it includes all administrative streets and blocks in the 31 provinces over mainland China [14]. NDMCD was designed to establish a management paradigm suitable for effective surveillance of drug use and related diseases in China [14]. Data were collected by government staffs, and drug types used by PWUDs were verified by urine tests, which are more accurate than data from questionnaires of sentinel surveillance sites [14,15,16]. All PWUDs registered in NDMCD would receive community-based or institute-based help, education and detoxification treatment [16]. Additionally, among PWUDs who need to receive detoxification treatment, HIV testing service is provided before they enter detoxification centers.

Taken together, HIV infections among PWIDs is an essential public health concern in China, and has important implications in HIV control; however, studies of nationwide HIV epidemic among PWIDs in recent years were scarce. Therefore, this study aims to assess the epidemic of HIV among PWIDs in detoxification centers nationwide from 2008 to 2016 by analyzing data extracted from the NDMCD, and we examine the HIV prevalence and its trends in PWIDs.

Methods

Definitions

PWUDs: Individuals have been found ever used prohibited psychotropic and narcotic drugs for non-medical purposes and registered in the NDMCD.

PWIDs: Individuals had self-reported ever IDU behavior and be recorded in the NDMCD.

New entrants in detoxification centers: Drug users who entered in detoxification centers were tested HIV for the first time. According to the guideline of “measures for the judgment of drug addiction,” the professional medical workers judged whether PWUDs need to enter the detoxification centers for drug treatment. PWUDs received drug-related diagnosis and evaluation, treatment, rehabilitation training, and educational and psychological correction. PWUDs in the detoxification centers must receive two years’ inpatient treatment.

HIV prevalence: HIV prevalence was calculated by the number of HIV-positive individuals (numerator) divided by the number of individuals who had done HIV test (denominator) among new entrants in detoxification centers, stratified by year.

Study design and study sample

New entrants who were PWIDs in detoxification centers tested for HIV between 2008 and 2016 were included in this analysis. Individuals who had no sociodemographic characteristics data were excluded. A total of 103,623 PWIDs were extracted from NDMCD. We excluded four individuals without sociodemographic characteristics data; finally, 103,619 PWIDs were included in the analysis.

PWUDs received HIV test service before entered detoxification centers. All new entrants in detoxification centers also needed to report IDU behavior and the HIV test registered in NDMCD from Jan 2008 to Aug 2016. We extracted sociodemographic characteristics, HIV test date and region, drug types and methadone treatment status before HIV test from the database.

The diagnosis of HIV infection by serological tests included both the screening test and the confirmation test based on "Diagnostic criteria for HIV/AIDS". HIV-positive PWUDs who meet the Chinese national treatment criteria (WHO stage 3 or 4 disease or CD4 count of 350 cells per μl or less) were referred for treatment with standard three-drug therapy. Primary outcomes were the prevalences and trends in HIV infection among total PWIDs, and secondary outcomes were the prevalences and trends in HIV infection among sub-populations, stratified by socio-demographic characteristics, drug types, HIV-related variables and risk factors related to HIV infection.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression models were conducted to calculate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs and AORs), respectively, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the HIV prevalence by characteristics [i.e., sex (male and female), age (≤ 24, 25–44, and ≥ 45 years), ethnicity (Han and minority), education (primary school or below, junior high school, and high school or above), marital status (divorced or widowed, married, and unmarried), and methadone treatment status before HIV test (yes or no)]. We also evaluated differences in the HIV prevalence among seven regions of China [northeast (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning), north (Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, and Tianjin), east (Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Anhui), central (Henan, Hubei, and Hunan), south (Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan), southwest (Yunnan, Xizang, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Guizhou), and northwest (Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Shaanxi)]. Sex, age, ethnicity, education, marital status, and methadone treatment status before HIV test, HIV test year and geographical regions were included into the adjusted analyses.

Joinpoint regression was used to examine the changing trend in the HIV prevalence during the study period. Annual percent change (APC) for each line segment and the corresponding 95% CI were estimated. The APC was tested to determine whether a difference existed from the null hypothesis of no change (0%). Each joinpoint informed a change in trends (increase or decrease) and each of trends was described by an APC.

A two-sided p value of 0.05 or less was defined as significant. Original data were double checked in PostgreSQL 9.3 and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical analyses were carried out and verified by using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS INSTITUTE INC). Trend analysis was done with Joinpoint Regression Program 4.6.0. Mapping was done with ArcGIS, version 10.0 (Esri).

Results

Demographical characteristics of the study sample

103,619 PWIDs were included in the analysis. In the total sample (n = 103,619 PWIDs), 89.3% (n = 92,548) were male, median age was 35 years old (IQR: 30–41), 84.7% (n = 87,816) was Han ethnicity, 86.6% (n = 89,782) had a junior school or below education, 53.0% (n = 54,853) were non-marital status, 99.3% (n = 102,850) ever used opioids drugs, and 79.6% (n = 82,431) never received methadone treatment before entered detoxification centers (Table 1). The residences of all PWIDs included south (30.2%), east (23.1%), central (18.4%), and southwest (16.7%) in China.

HIV prevalence and risk factors

Among 103,619 PWIDs, the HIV prevalence was 5.0% (Table 2). The HIV prevalence among female PWIDs was 5.2%, which was higher than 5.0% among male PWIDs (AOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.15–1.39, p < 0.001). Elder age had a higher risk of HIV infection (HIV prevalence 25–44 vs < 25: 5.2% vs 3.1%, AOR 2.31, 95% CI 2.03–2.64, p < 0.001; ≥ 45 vs < 25: 5.0% vs 3.1%, AOR 2.57, 95% CI 2.20–3.00, p < 0.001). 12.3% of minority PWIDs were HIV positive, and were more likely to be HIV infected compared to 4.1% of Han PWIDs (AOR 2.61, 95% CI 2.43–2.80, p < 0.001). Compared with the HIV prevalence (2.9%) of people who had high school or above education, people who had junior school education had a higher risk of HIV infection (AOR 1.41, 95% CI 1.26–1.59, p < 0.001), similar to primary school or below education (AOR 2.00, 95% CI 1.77–2.26, p < 0.001). Additionally, there was no statistical difference in the HIV prevalence between PWIDs with ever opioids injection and those without opioid injection. Individuals who received methadone treatment before were more likely to be infected HIV (AOR 1.59, 95% CI 1.49–1.71, p < 0.001).

Trends in the HIV prevalence

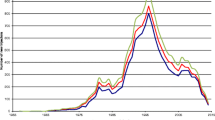

A U-shaped curve with 33% decrease (APC − 20.6, 95% CI − 32.5 to − 6.7, p < 0.05) in the HIV prevalence from 4.9% in 2008 to 3.3% in 2010 and subsequently 161% increase (APC 17.9, 95% CI 14.5–21.4, p < 0.05) from 3.3% in 2010 to 8.6% in 2016 was observed among PWIDs (Table 2, Fig. 1). After adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, HIV test region, drug types, and methadone treatment status, the U-shaped trend in HIV infections among PWIDs was still observed (Additional file 1: Table S1). Furthermore, subpopulations of HIV infections among PWIDs, such as male [a decrease (APC − 20.9, 95% CI − 35.9 to − 2.3, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2010 and an increase (APC 17.6, 95% CI 13.3–22.1, p < 0.05) from 2010 to 2016], young adults (24–45 years old) [a decrease (APC − 21.9, 95% CI − 34.6 to − 6.8, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2010 and an increase (APC 17.6, 95% CI 13.6–21.7, p < 0.05) from 2010 to 2016], minority [a decrease (APC − 38.1, 95% CI − 55.7 to − 13.6, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2010 and an increase (APC 10.8, 95% CI 3.6–18.4, p < 0.05) from 2010 to 2016], married people [a decrease (APC − 24.7, 95% CI − 42.7 to − 1.2, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2010 and an increase (APC 21.9, 95% CI 16.2–27.9, p < 0.05) from 2010 to 2016], and opioids users [a decrease (APC − 20.9, 95% CI − 33.2 to − 6.3, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2010 and an increase (APC 18.1, 95% CI 14.6–21.8, p < 0.05) from 2010 to 2016], all showed U-shaped curves for the HIV prevalence. In addition, other subpopulations, such as female, people over 45 years old, Han ethnicity, and non-marital people, all presented increased trends in recent years (Fig. 1).

Geographical differences in HIV infections

The HIV prevalence in southwest was 13.2%, higher than other regions (Table 2). A decreased trend (APC − 10.0, 95% CI − 15.5 to − 4.1, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2013 was observed in southwest (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Also, the decreased trend (APC − 27.2, 95% CI − 42.2 to − 8.4, p < 0.05) was observed in northwest. Yet an increased trend (APC − 27.2, 95% CI − 42.2 to − 8.4, p < 0.05) of the HIV prevalence was observed in south from 2011 to 2016. The HIV prevalence in north, central and east regions all presented the increased trends (North: APC 15.7, 95% CI 2.7– 30.4, p < 0.05; East: APC 27.6, 95% CI 18.1– 37.8, p < 0.05; Central: APC 29.8, 95% CI 20.0– 40.4, p < 0.05) from 2008 to 2016 (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Discussion

Overall, the HIV prevalence among PWIDs from China’s national data was 5.0%, which was higher than that among the general population (around 0.6‰) [11]. The HIV prevalence among PWIDs presented the U-shaped trend, which decreased from 4.9% in 2008 to 3.3% in 2010 and subsequently increased from 3.3% in 2010 to 8.6% in 2016. Although the HIV prevalence in west regions in China presented decreased trends, it was still the most prevalent area of HIV epidemic.

In China, HIV infection among drug users mainly arose from PWIDs by needle sharing [9, 12]. The WHO recommends that NSPs can effectively reduce HIV transmission among PWIDs, and a meta-analysis also suggested that NSPs were associated with a 58% reduction in HIV transmission [17]. China initiated the first NSP in Yunnan Province in 1998, which gradually has become a nationwide program through the support of The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and international programs since 2004 [18]. By the end of 2005, over two-thirds of NSP sites were located in southern and western provinces where the HIV among drug users was much more prevalent [19]. And the number of NSP sites increased over years, by 2010, the national government has established about 1000 NSP sites covered at least 50% of PWIDs nationwide [12, 20]. Wei Luo et al. explored the relationship between NSP and HIV infection across China, and found that in 2010, 1928 of 3494 (55.2%) interviewed PWIDs had ever attended NSP at least once; the unadjusted HIV prevalence of NSP non-attendees was 16.5%, which was 1.67 times more likely to be HIV-positive compared to 13.9% of HIV infections among NSP attendees [21]. Due to the expanded NSP coverage in China, the prevalence of HIV among PWIDs have been reduced about one third (from 4.9% in 2008 to 3.3% in 2010) reported by our study.

Although China has scaled up NSPs, it has not been extensively evaluated to explore factors associated with the acceptability and feasibility [22]. In-depth qualitative interviews with 35 PWIDs identified themes including fears of breached confidentiality, police interference in NSP sites, and tensions between the public health and law enforcement perspective [23]. Lei Zhang et al. suggested that continued law enforcement and mandatory detoxification remain as major barriers to the necessary program scale-up that may even counteract the benefits of NSPs [23]. Ongoing police crackdowns, arrests, and confinement substantially discourage PWIDs from contacting peer health educators and accessing to NSP sites [23]. NSP should be expanded to include those who had not yet attended the program before, but there are few relevant data and reports on nationwide NSP after 2010. UNAIDS 2020 data reported a high coverage of needle-syringe programs (246 needles and syringes per person who injects drugs per year) in China, but the coverage might be overestimated because those who had not yet attended the program were not included in the statistics [24]. After 2010, a more than two times (from 3.3% in 2010 to 8.6% in 2016) increased HIV prevalence among PWIDs was observed in this study, which was not consistent with the notification of the decreased HIV transmission by IDU reported by China CDC [11]. However, the lack of NSP-related data made the cause of the trend obscure, and our findings implied that the promotion and effectiveness of NSP needs to be further evaluated.

Since 2005, HIV transmission due to IDU in China has been no longer the major transmission route, and the percentage of HIV infections due to IDU has decreased rapidly from 48.6% in 2005 to 3.8% in 2016 [11, 12]. However, our findings suggest that higher HIV prevalence among PWIDs, which increased over time (Table2, Fig. 1). Females, elder ages, minorities, the lower education, and the unmarried were associated with higher risk of HIV infection among PWIDs. In recent years, the proportion of female PWIDs infected with HIV continues to increase, and the HIV prevalence of other people getting infected through sexual transmission from female PWIDs is on the rise [25]. Condom promotion and mother-to-child prevention work have become the priority [26]. A prospective cohort study of 636 male PWIDs without HIV infection showed that lack of formal education was associated with loss of follow-up, which affected the rate of new HIV infections among PWIDs [27].

In our study, an intriguing finding was that individuals who received MMT before were more likely to be HIV infected was observed. Though it has been reported that MMT is associated with reduction in the risk of HIV infection among PWIDs, and syringe sharing behaviors in MMT groups diminished substantially [28, 29]. It needs to be emphasized that in terms of therapeutic effectiveness, greater benefit might be associated with longer duration of exposure to MMT and good adherence [28, 29]. However, in our study, these PWIDs who received MMT before entered detoxification centers, which showed the failure of MMT they received. And it might because they were more addicted to drugs, or the interference of other adverse factors. This phenomenon showed that the failure of MMT can pose a greater risk. Therefore, we need to focus not only on whether to receive MMT, but also on the effectiveness and outcome of the MMT. Key actions should be taken to strengthen the management of patients in MMT programs, and to improve the treatment adherence and success rate.

From a spatial perspective, our findings indicated that the HIV prevalence among PWIDs in southwest and northwest regions presented decreased trends, and both regions were traditional epidemic areas of opioids abuse with high risk of HIV infection [12]. Our results show that NSP programs might achieve some success in reduced HIV transmission in western regions, but the HIV prevalence among PWIDs in eastern region presented an increased trend. In 2009, Wei Guo’s study concluded that the proportion of PWIDs in central region maintained at about 50% among all drug users, and suggested that, once the number of HIV infections of drug users reached a high level, it was likely to cause a rapid increase in the HIV prevalence among drug users in this area [26]. Central and eastern regions in China contain population densities of > 450 people per square kilometer and account for about 46% of China’s population [30]. This finding implies that the government needs to become more aware of the risk of HIV transmission to the general population.

The HIV prevalence in our study could provide more valuable information on HIV epidemic than the number of HIV infections reported by China CDC. Yet, our study has several limitations. First, this is a series cross-sectional study rather than a cohort study, thus the HIV prevalence might contain bias. Second, the PWIDs sample undergoing detoxification in this study may have been injecting longer than other PWIDs, and therefore this study might have a higher HIV prevalence and may overestimate the prevalence among PWIDs. The last, the limited available data make it hard to draw conclusions what actually led to the increase in the HIV prevalence among PWIDs. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the HIV prevalence among the largest population of PWIDs nationwide in China. The unexpected findings of the U-shaped curve for the HIV prevalence among PWIDs suggest that current strategies on the HIV prevention and control among PWIDs might no longer be effective, and the reassessment is urgently needed.

Conclusions

The U-shaped curve of the HIV prevalence among PWIDs implies that IDU might still be a critical transmission route of HIV infections in China. Besides the implementation of traditional model of HIV prevention, it is necessary to continue to strengthen the coverage and promotion of NSP and MMT, and pay attention to the quality of service, especially the management of MMT treatment adherence, and formulate a regular mechanism to evaluate effectiveness of comprehensive interventions. In addition to detoxification treatment, a sound social support network is needed with the community as the core. In our study, female, elder people, minority, lower education are exposed to HIV risk associated with IDU. Indicated prevention strategies should target these sub-populations. The western regions, which were traditional HIV high risk areas, the intervention of IDU is still the key point.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infectious diseases, opioids and injection drug use. 2018 Jul 19 [cited 2019 Nov 15]. https://www.cdc.gov/pwid/opioid-use.html.

Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Novick DM, et al. HIV-1 infection among intravenous drug users in Manhattan, New York City, from 1977 through 1987. JAMA. 1989;261:1008–12.

Larney S, Peacock A, Leung J, et al. Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1208–20.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1192–207.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2018. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/unaids-data-2018.

Zheng X, Tian C, Yang G. Preliminary investigation and analysis of drug use behavior and risk factors of HIV infection in 225 drug users in Ruili county, Yunnan province. China Chin J Epidemiol. 1991;12:12–4.

Bao Y, Liu Z. Systematic review of HIV and HCV infection among drug users in China. Int J Std Aids. 2009;20:399–405.

Zhan SY, Ye DQ, Tan HZ. Epidemiology. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2012. p. 492.

NCAIDS, NCSTD, China CDC. Update on the AIDS/STD epidemic in China in December, 2016. Chin J AIDS STD. 2017;23:93.

Burki T. HIV in China: a changing epidemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1311–2.

Zhang LD, Chow EPFM, Jing JP, et al. HIV prevalence in China: integration of surveillance data and a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:955–63.

Wang L, Guo W, Li D, et al. HIV epidemic among drug users in China: 1995–2011. Addiction. 2015;110:20–8.

Zhang L, Chow E, Zhang J, et al. Describing the Chinese HIV surveillance system and the influences of political structures and social stigma. The Open AIDS Journal. 2012;6:163–8.

Zhang G, Jiang H, Shen J, Wen P, Liu X, Hao W. Estimating prevalence of illicit drug use in Yunnan, China, 2011–15. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:256.

The UN Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China. HIV/AIDS: China's Titanic Peril—2001 Update of the AIDS Situation and Needs Assessment Report 2002.

Anti-Drug Law of the People’s Republic of China. Chapter IV A 32. Public security organs shall have the drug users registered. http://www.china.org.cn/china/LegislationsForm2001-2010/2011-02/11/content_21899159.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

WHO, UN Office on Drugs and Crime, UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. Technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users—2012 revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Wu Z, Lin P, Liu W, Ming ZQ, Pang L. Randomized community trial to reduce HIV risk behaviors among injecting drug users using needle social marketing strategies in China. In: 15th international AIDS conference, Bangkok, Thailand, July 11–16 2004. LbOrC16.

Liu B, Sullivan SG, Wu Z. An evaluation of needle exchange programmes in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S123–8.

Li J, Li X. Current status of drug use and HIV/AIDS prevention in drug users in China. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:S37–41.

Luo W, Wu Z, Poundstone K, et al. Needle and syringe exchange programmes and prevalence of HIV infection among intravenous drug users in China. Addiction. 2015;110:61–7.

Philbin MM, FuJie Z. Exploring stakeholder perceptions of facilitators and barriers to using needle exchange programs in Yunnan Province China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86873.

Zhang L, Chen X, Zheng J, et al. Ability to access community-based needle-syringe programs and injecting behaviors among drug users: A cross-sectional study in Hunan Province. China Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:8–8.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS Data 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/unaids-data. Accessed 24 May 2021.

Wang Y. Survey on female drug users in Zhejiang Province. J Chin People’s Public Security University (Social Sciences edition). 2008;24(6):149–56 ((in Chinese)).

Guo W, Qu SQ, Ding ZW, Yan RX, Li DM, Wang L. Situations and trends of HIV and syphilis infections among drug users in China, 1995–2009. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2010;31(6):666–9.

Samo RN, Altaf A, Shan SA. Risk factors for loss to follow-up among people who inject drugs in a risk reduction program at Karachi, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):1–11.

MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, Vickerman P, Deren S, Bruneau J, Degenhardt L, Hickman M. Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5945.

Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stöver H, Møller L, Mayet S. The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(3):501–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03676.x.

National Bureau of Statistics. China statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2017.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China and the Beijing Advanced Discipline Construction Project funded. The opinions expressed herein show the collective views of the co-authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of fundings.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 91546203, 91846302], the Chinese Ministry of Public Security [0716-1541GA590508], the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China [2020YFC0849200] and the Beijing Advanced Discipline Construction Project [BMU2019GJJXK005].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZJ, ZLu, and BZ designed the study. BZ and LLiu cleaned the data. BZ, XY and YL analyzed the data. ZJ, ZLu, BZ, and ZLiu explained the results. ZJ and BZ wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. ZJ, ZLu and ZH revised the manuscript from the preliminary draft to submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study is a secondary data analysis. The data we have were anonymized by the government to protect the privacy of persons who use drugs, and this study did not access any individually identifiable data, and thus ethical approval was waived by Peking University Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Univariate and multicariate analysis of HIV infection among PWIDs in China, 2008–2016.

Additional file 2

. Trends in the prevalence of HIV infection among PWIDs by regions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Yan, X., Li, Y. et al. Epidemic of HIV infection among persons who inject drugs in mainland China: a series, cross-sectional study. Harm Reduct J 18, 63 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00511-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00511-6