Abstract

Background

It is apparent that the interaction between platelets and eosinophils plays a critical role in the activation of allergic inflammation. We investigated whether blocking of the glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptor can attenuate allergic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness through inhibition of platelet–eosinophil aggregation (PEA) in asthma.

Methods

BALB/c mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of ovalbumin (OVA) on days 0 and 14, followed by 3 nebulized OVA challenges on days 28–30. On each challenge day, 5 mg/kg tirofiban was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the challenge. Mice were assessed for airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), airway inflammation, and the degree of PEA. Finally, the activation levels of platelets and eosinophils were evaluated.

Results

Tirofiban treatment decreased AHR and eosinophilic inflammation in Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) fluid. This treatment also reduced the levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in BAL fluid and airway inflammatory cell infiltration in histological evaluation. Interestingly, the blocking of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor more reduced PEA in both blood and lung tissue of tirofiban-treated mice than in those of the positive control mice, and both eosinophilic and platelet activations were attenuated in tirofiban-treated mice.

Conclusions

The blocking of GP IIb/IIIa receptor with tirofiban can attenuate AHR and airway inflammation through the inhibition of PEA and activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Platelets are well-known primary cells in the hemostasis and tissue repair process, and they are also known as effector cells in chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma [1]. Platelet activation has been observed in allergic diseases since 1972 [2], and increased release of chemokines and mediators from platelets, such as platelet factor (PF) 4 and RANTES, were found in asthmatic patients after bronchial challenge [3, 4]. Asthmatic patients have also been reported to have mild thrombocytopenia [5] and to have more shortened platelet lifespan in the circulation than healthy controls [6]. These results mean that continuous platelet activation may play a role in the pathogenesis of asthma.

The platelet–leukocyte interaction is a fundamental cellular process that is characterized by the exchange of signals between platelets and different types of leukocytes in atherosclerosis and inflammatory reactions. This interaction can amplify the synthesis of pro-inflammatory compounds such as the leukotrienes and thromboxane A2. In asthma, the frequency of platelet-adherent leukocytes, especially eosinophils, is strikingly increased in the blood of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) patients [7], and the degree of platelet–leukocyte aggregation (PEA) are elevated in the blood and nasal polyp of AERD where cysteinyl leukotrienes are their main pathogenesis [8]. Moreover, AERD patients who had greater baseline platelet activation completely inhibited all aspirin-induced symptoms after treatment with P2Y12 receptor antagonism, prasugrel [9]. Platelet–leukocyte interactions are also found in other inflammatory diseases except asthma. For example, platelet activation and coagulation abnormalities were found in inflammatory bowel disease patients [10], and the platelet to lymphocyte ratio was correlated with the disease severity of systemic lupus erythematosus patients [11]. These results highlight the potential for the role of platelets in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases [12]. However, the clinical significance of platelet activation in pathologic mechanisms and its use for asthma therapy have not been elucidated. Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the respiratory tract, and many asthmatics are eosinophil-dominant. Therefore, most asthmatic patients are well controlled with inhaled corticosteroid treatment [13]. However, a considerable number of asthmatic patients are not controlled after treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid, which leads to an urgent unmet need for new therapeutic strategies.

When platelets are activated and aggregated with leukocytes, they can directly interact with other cells via contact-dependent or soluble mediator-dependent mechanisms [14]. P-selectin/P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1), CD40/CD40 ligand, and the glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptor are involved in contact-dependent interactions [7], and cysteinyl leukotrienes, which can bind to P2Y12 receptor, are well known as soluble mediator-dependent factors. In our previous study, the inhibition of the P2Y12 receptor, which is a soluble mediator-dependent factor in clopidogrel treatment, has been shown to attenuate airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness through diminishing the platelet–eosinophil interaction as well as platelet‐dependent eosinophil recruitment and degranulation in the asthma mouse model [15]. However, there have been few studies on direct contact-dependent interactions between platelets and leukocytes in asthma. The GP IIb/IIIa receptor is known as a major factor for contact-dependent interactions between platelets and leukocytes [16], and the blocking effect of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor by tirofiban which is a GP IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor widely used for cardiovascular and antithrombotic effects [17].

In this study, we hypothesized that blocking of the direct contact-dependent interaction between platelets and eosinophils will reduce the formation of PEA as well as platelet and eosinophil activations. We also compared the blocking effects of GP IIb/IIIa and P2Y12 in an eosinophilic asthma model, which could decrease asthma symptoms in an eosinophilic asthma model and have the therapeutic potential for new asthma treatment.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice (6 weeks old; weight, 20 ± 2 g) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. All animal experiments conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ajou University (IACUC 2017-0068).

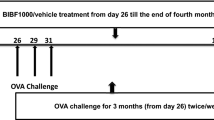

Eosinophilic asthma mouse model and tirofiban treatment

BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally sensitized with 10 µg/mg ovalbumin (OVA) and aluminum hydroxide solution on days 0 and 14, followed by 3 nebulized OVA challenges on days 28–30 using an ultrasonic nebulizer (NE-SM1; Ktmed Inc., Seoul, South Korea) [18]. On each challenge day, 5 mg/kg tirofiban was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the challenge. The mice were assayed for the next experiments 48 h after the last challenge.

Airway resistance measurement and sample collection

The FlexiVent system (Scireq, Montreal, QC, Canada) was employed to measure airway resistance. On the day indicated, the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium and intubated with a cannula. After connecting them to a computer-controlled small-animal ventilator, the mice were ventilated with a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg at a frequency of 150 breaths/min. The baseline airway resistance (RL) of each mouse was recorded. Subsequently, a dilution series of acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride (MCh) from 3.12 to 50 mg/mL were gradually introduced to the mice, and the RL values at each concentration were recorded.

Harvest of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung histology analysis

After measuring airway resistance, BAL fluid was harvested with a wash of 1 mL of PBS plus 2 % bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After the BAL fluid was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, leukocytes were quantified with a hemocytometer, and differential cell counts were performed by counting at least 200 cells on cytospin slides stained with Wright–Giemsa stain. The supernatant was collected and stored at − 70 °C until further analysis. Tissue sections were evaluated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). To detect inflammatory cells, sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and mucus-containing cells were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). The number of inflammatory cells per µm2 of perivascular and peribronchial areas and the number of mucus-containing cells per µm2 of basement membrane were determined.

Measurement of cytokine levels

The levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), PF-4 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) (MyBiosource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) in the BAL fluid were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Identification of PEA in whole blood

Flow cytometry of PEA in whole blood was performed as previously described [19]. Mouse whole blood was harvested by cardiac puncture into tubes containing 3.8 % sodium citrate to prevent coagulation. The whole blood was incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse Siglec-F and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD41 for 30 min at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Next, red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed with the RBC Lysis/Fixation solution (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 10 min and washed once with 1× PBS. The cells were analyzed immediately by flow cytometry with the BD FACSCanto II (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described [19]. A leukocyte gate was set in terms of size and granularity. Within the leukocyte gating, eosinophils were labeled by PE-conjugated anti-mouse Siglec-F. PEA was identified as CD41+ eosinophils (Siglec-F+/CD41+), and at least 1000 events were recorded for each sample. A pooled sample from 3 mice was used to obtain a sufficient number of eosinophils for the analysis.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF was performed using the immunofluorescence technique on 5 μm-thick paraffin sections. After deparaffinization, tissue sections were sequentially incubated with blocking buffer (0.05 % PBS-Tween 20 containing 5 % bovine serum albumin and 10 % normal donkey serum) for 1 h at RT and then incubated with rabbit anti-eosinophil peroxidase (EPX) antibody (Bioss Antibodies), rat anti-PSGL-1 antibody (Ray Biotech) overnight at 4 °C. For IF labeling, the sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies. The Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rat antibody (Life Technologies) and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Life Technologies) were applied for 50 min at 37 °C. Finally, after nuclear staining with DAPI (0.5 µg/mL) for 5 min, biomeda mounting solution (Biomeda) was dropped on the glass slide, and the coverslips were inverted and placed onto glass microscope slides.

Detection MAC-1 of by western blotting

Thirty-five micrograms of protein was isolated from each tissue homogenate with RIPA buffer. Proteins was separated 12 % SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Blocking in 5 % skim milk (Sigma Aldrich) in Tris buffered saline containing 0.01 % Tween 20 (TBST-T) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies against MAC-1 (bs-1014R, Bioss antibodies) and β-actin antibody (sc-47,778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as an internal control. After extensive washing in Tween-TBS, The membranes were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Antibody binding was visualized using an ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), and images were acquired using a gel doc system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies used against the mouse target proteins were anti-PSGL-1 antibody (Q14242; Ray Biotech, USA), anti-EPX antibody (bs-3881R; Bioss Antibodis), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21206), and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG (A21209) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP)-conjugated anti-Ly6G (127,654, Biolegend), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated CD11c (117,309, Biolegend), PE-conjugated anti-Siglec-F (552,126, BD Bioscience), FITC-conjugated anti-CD41 (133,904, Biolegend), and PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-CD62P (148,310, Biolegend) antibodies were used for flow cytometry and cell sorting. All drugs used for treatment were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless indicated otherwise.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. The differences between treatment groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test unless indicated otherwise. The differences between the stimulated and control cells in the in vitro assay were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Tirofiban administration attenuates AHR and airway inflammation in BAL fluid and lung tissue

To determine the therapeutic effects of tirofiban on OVA-induced AHR and airway inflammation in the eosinophilic asthma model, mice were treated with 5 mg/kg tirofiban at the OVA-challenge phase. Airway responses to inhaled MCh were more attenuated and eosinophil counts were more decreased in tirofiban-treated mice than in the positive control mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A, B). Also, the BAL fluid levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were more reduced in the tirofiban-treated mice than in the positive control mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Histopathological examination revealed peribronchial and perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration in the positive control mice; however, tirofiban treatment significantly decreased the numbers of inflammatory cells and PAS-positive mucus-containing goblet cells in lung tissue (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Tirofiban suppresses PEA in mouse blood

Platelets have been investigated whether they aggregate with eosinophils in the blood and BAL fluid of asthmatic patients, especially with asthma exacerbation [20]. Therefore, PEA formation was evaluated on the basis of cells containing CD41 and siglec-F in mouse whole blood using the FACS method. The percentage of PEA was increased in the positive control mice than in the negative control mice (19.4 % vs. 5.4 %). In contrast, the increased level of PEA (9.0 %) was significantly decreased by tirofiban treatment in mouse whole blood (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Moreover, the ratio of eosinophils which attached to platelets was calculated. These ratios were 1.26, 0.94, and 1.56 in control, OVA, and tirofiban groups, respectively. This result means that eosinophils attached to platelets are increased in asthmatic mice, and these cells are reduced after tirofiban treatment.

Tirofiban inhibits both platelet and eosinophil activations in BAL fluid and lung tissue

Next, the activation markers of platelets and eosinophils were measured in BAL fluid. The BAL fluid levels of PF4 and ECP were more elevated in the positive control mice than in the negative control mice. However, both activations markers were more effectively suppressed in the tirofiban-treated mice than in the positive control mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

The activation markers were also evaluated in lung tissue. The levels of P-selectin and EPX were measured using the immunofluorescence method. The expression of EPX and PSGL-1 was markedly increased in the positive control mice, but the increased levels of EPX and PSGL-1 were significantly abrogated by tirofiban treatment in mouse lung tissue (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). The data are quantified in Fig. 5B.

Tirofiban decreases adhesion molecule on eosinophil surface

MAC-1 on eosinophil is the well-known ligand of GPIIb/IIIa on platelet in PEA formation. Therefore, the levels of MAC-1 were measured in lung homogenate after tirofiban treatment by western blot. The expression levels of MAC-1 were significantly enhanced in the positive control mice compared to negative control mice, but these levels were significantly decreased by tirofiban treatment in lung homogenate (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6).

The comparative effect of tirofiban and clopidogrel in the eosinophilic model of asthma

The GP IIb/IIIa receptor which can be blocked by tirofiban is a representative contact-dependent mediator for platelet–leukocyte interaction; in contrast, P2Y12 receptor which can be antagonized by clopidogrel is a soluble mediator related mediator on platelet–leukocyte interactions. Finally, their blocking effects were compared with our previous results in the eosinophilic asthma model [19]. When the results of OVA-positive control mice were designated as 100 %, the blocking effects of tirofiban and clopidogrel treatments were calculated as decreased percentages.

All asthma parameters, including AHR and type 2 inflammation markers, were decreased after clopidogrel or tirofiban treatments. However, the inhibitory effects of these 2 treatments were not significantly different.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence suggests that platelets play a critical role in immunity and inflammation besides their well-known role as a cellular mediator in thrombosis. Platelets can contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis, transplant rejection, rheumatoid arthritis, and asthma directly through contact-dependent mechanisms or indirectly through secreted immune mediator-driven mechanisms [14]. Interactions between platelets and inflammatory cells usually promote pro-inflammatory action and can have a beneficial effect on the inflammatory process. However, exaggerated platelet interactions with leukocytes can lead to adverse effects of excessive immune stimulation and harmful inflammatory results. Increased platelet–neutrophil aggregation was found in acute coronary syndrome, which leads to cardiac dysfunction and vascular plaque formation [21]. Activated platelets aggregate with leukocytes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [22], nephritis [23], or skin contact hypersensitivity [24]. The therapeutic effects of tirofiban have been suggested in some previous studies. Selective platelet inhibition by tirofiban resulted in reduced leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions in antigen induced arthritis [25], and antiplatelet therapy with tirofiban even showed effective improvement in the ventilation/perfusion ratio in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure [26]. Clinical importance of platelet–leukocyte interactions, especially eosinophils, has been reported in asthmatic patients. Platelet depletion can reduce eosinophilic inflammation of the lung and decrease hyperresponsiveness in mouse asthma models [27]. Many eosinophils attached to platelets was observed in blood from asthmatic patients [8], and the administration of prasugrel, which is P2Y12 receptor antagonist showed decreased airway hyperresponsiveness compared to control treatment in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study [28]. Taken together, the pathological role of platelets is strongly suggested in asthma, but not clearly understood especially as a therapeutic target.

Platelets can interact with other blood cells via 2 different ways: contact-dependent or soluble mediator-dependent. Our previous study demonstrated significant therapeutic effects of platelets and decreased PEA in a mouse asthma model after the blockade of P2Y12 which is a soluble mediator of platelets [19]. The GP IIb/IIIa receptor which is an integrin complex is one of the representative contact-dependent mediators of platelets to aggregate with other blood cells [29]. In this study, we evaluated the blocking effect of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor by tirofiban in an eosinophilic asthma model and found that AHR, eosinophilic inflammation, and the levels of type 2 inflammatory markers were significantly more decreased in the tirofiban-treated mice than in the positive control mice. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report regarding the blocking effect of GP IIb/IIIa in asthma. So far, tirofiban has been used primarily in heart and vascular diseases [30, 31]. However, tirofiban has a therapeutic effect in chronic inflammatory diseases other than coronary disease by its involvement in the interaction between platelets and other blood cells [32]. Selective inhibition of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor by tirofiban significantly reduces platelet–endothelium interactions, which reduces knee-joint diameter in antigen-induced arthritis [25]. Although there are not a few publications about the blocking effect of GP IIb/IIIa in chronic inflammatory diseases other than coronary disease, other integrin families have been under investigation as therapeutic candidates due to their key role in cellular trafficking and activation [33, 34].

Importantly, PEA was more reduced in the tirofiban-treated mice than in the positive control mice and is the hallmark of allergic asthma after allergen challenge, which leads to platelet and eosinophil activations [27, 35]. Therefore, the activation levels of platelets and eosinophils were measured after the GP IIb/IIIa receptor was blocked with tirofiban. Platelets express a variety of chemokine receptors, immunoglobulin receptors, toll-like receptors, and adhesion molecules. They also store inflammatory mediators such as PF4 [36,37,38,39], and ECP is a well-known eosinophil chemoattractant and an augmenting agent for eosinophil adhesion [12]. We found that the activation of these markers was effectively suppressed by tirofiban treatment in BAL fluid and that the expression levels of EPX and PSGL-1 were significantly abrogated by tirofiban treatment in mouse lung tissue. PF4 and EPX are known to directly contribute to the induction of AHR in asthma models [40, 41]. Therefore, it is speculated that the therapeutic effects of tirofiban may rely on interactions between platelets and eosinophils.

Finally, we compared the blocking effects of tirofiban and clopidogrel administration in the same asthma model. As shown in Table 1, the therapeutic effect of clopidogrel seems more beneficial than that of tirofiban, albeit without any statistical significance. The P2Y12 receptor is more expressed in various immune cells than the GP IIb/IIIa receptor. Eosinophils, which are the most important effector cells in asthma, posses the P2Y12 receptor; dendritic cells, mast cells, lymphocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells also express this receptor on their surface [42]. In contrast, the GP IIb/IIIa receptor is specifically expressed on platelets and have strong cell-specific properties. Therefore, the combination of clopidogrel and tirofiban would be warranted in future asthma studies.

Conclusions

The blocking of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor with tirofiban can significantly inhibit PEA as well as platelet and eosinophil activation, thereby attenuating AHR and airway inflammation in an eosinophilic asthma model. The results of this study suggest that the GP IIb/IIIa receptor can be used as a novel therapeutic target for asthma.

Availability of data and materials

All data and models used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Abbreviations

- OVA:

-

Ovalbumin

- AHR:

-

Airway hyperresponsiveness

- GP:

-

Glycoprotein

- AERD:

-

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

- PEA:

-

Platelet–leukocyte aggregation

- PSGL-1:

-

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

- ECP:

-

Eosinophilic cationic protein

- EPX:

-

Eosinophil peroxidase

- PF:

-

Platelet factor

- MCh:

-

Acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

References

Golebiewska EM, Poole AW. Platelet secretion: from haemostasis to wound healing and beyond. Blood Rev. 2015;29(3):153–62.

Benveniste J, Henson PM, Cochrane CG. Leukocyte-dependent histamine release from rabbit platelets. The role of IgE, basophils, and a platelet-activating factor. J Exp Med. 1972;136(6):1356–77.

Yasuba H, Chihara J, Kino T, Satake N, Oshima S. Increased releasability of platelet products and reduced heparin-induced platelet factor 4 release from endothelial cells in bronchial asthma. J Lipid Mediat. 1991;4(1):5–21.

Hasegawa S, Tashiro N, Matsubara T, Furukawa S, Ra C. A comparison of FcepsilonRI-mediated RANTES release from human platelets between allergic patients and healthy individuals. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2001;125(Suppl 1):42–7.

Kowal K, Pampuch A, Kowal-Bielecka O, DuBuske LM, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A. Platelet activation in allergic asthma patients during allergen challenge with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(4):426–32.

Taytard A, Guenard H, Vuillemin L, Bouvot JL, Vergeret J, Ducassou D, et al. Platelet kinetics in stable atopic asthmatic patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134(5):983–5.

Mitsui C, Kajiwara K, Hayashi H, Ito J, Mita H, Ono E, et al. Platelet activation markers overexpressed specifically in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(2):400–11.

Laidlaw TM, Kidder MS, Bhattacharyya N, Xing W, Shen S, Milne GL, et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease is driven by platelet-adherent leukocytes. Blood. 2012;119(16):3790–8.

Laidlaw TM, Cahill KN, Cardet JC, Murphy K, Cui J, Dioneda B, et al. A trial of type 12 purinergic (P2Y12) receptor inhibition with prasugrel identifies a potentially distinct endotype of patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):316–24. e7.

Matowicka-Karna J. Markers of inflammation, activation of blood platelets and coagulation disorders in inflammatory bowel diseases. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2016;70:305–12.

Qin B, Ma N, Tang Q, Wei T, Yang M, Fu H, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were useful markers in assessment of inflammatory response and disease activity in SLE patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26(3):372–6.

Idzko M, Pitchford S, Page C. Role of platelets in allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(6):1416–23.

Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, Coleman CI, White CM, Lazarus SC, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1485–96.

Morrell CN, Aggrey AA, Chapman LM, Modjeski KL. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood. 2014;123(18):2759–67.

Suh DH, Trinh HK, Liu JN, Pham le D, Park SM, Park HS, et al. P2Y12 antagonist attenuates eosinophilic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of asthma. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20(2):333–41.

Shah SA, Page CP, Pitchford SC. Platelet-eosinophil interactions as a potential therapeutic target in allergic inflammation and asthma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017;4:129.

Caron A, Theoret JF, Mousa SA, Merhi Y. Anti-platelet effects of GPIIb/IIIa and P-selectin antagonism, platelet activation, and binding to neutrophils. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;40(2):296–306.

Takeda K, Miyahara N, Kodama T, Taube C, Balhorn A, Dakhama A, et al. S-carboxymethylcysteine normalises airway responsiveness in sensitised and challenged mice. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):577–85.

Trinh HKT, Nguyen TVT, Choi Y, Park HS, Shin YS. The synergistic effects of clopidogrel with montelukast may be beneficial for asthma treatment. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(5):3441–50.

Ulfman LH, Joosten DP, van Aalst CW, Lammers JW, van de Graaf EA, Koenderman L, et al. Platelets promote eosinophil adhesion of patients with asthma to endothelium under flow conditions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28(4):512–9.

Sarma J, Laan CA, Alam S, Jha A, Fox KA, Dransfield I. Increased platelet binding to circulating monocytes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2002;105(18):2166–71.

Pamuk GE, Vural O, Turgut B, Demir M, Umit H, Tezel A. Increased circulating platelet-neutrophil, platelet-monocyte complexes, and platelet activation in patients with ulcerative colitis: a comparative study. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(10):753–9.

Kuligowski MP, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ. Leukocyte recruitment to the inflamed glomerulus: a critical role for platelet-derived P-selectin in the absence of rolling. J Immunol. 2006;176(11):6991–9.

Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N, Ueda E, Takenaka H, Kita M, Kishimoto S. The role of platelets in leukocyte recruitment in chronic contact hypersensitivity induced by repeated elicitation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(6):2019–29.

Schmitt-Sody M, Metz P, Gottschalk O, Zysk S, Birkenmaier C, Goebl M, et al. Selective inhibition of platelets by the GPIIb/IIIa receptor antagonist Tirofiban reduces leukocyte–endothelial cell interaction in murine antigen-induced arthritis. Inflamm Res. 2007;56(10):414–20.

Viecca M, Radovanovic D, Forleo GB, Santus P. Enhanced platelet inhibition treatment improves hypoxemia in patients with severe Covid-19 and hypercoagulability. A case control, proof of concept study. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158:104950.

Pitchford SC, Yano H, Lever R, Riffo-Vasquez Y, Ciferri S, Rose MJ, et al. Platelets are essential for leukocyte recruitment in allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(1):109–18.

Lussana F, Di Marco F, Terraneo S, Parati M, Razzari C, Scavone M, et al. Effect of prasugrel in patients with asthma: results of PRINA, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(1):136–41.

Pawelski H, Lang D, Reuter S. Interactions of monocytes and platelets: implication for life. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2014;6:75–91.

Kondo K, Umemura K. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tirofiban, a nonpeptide glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist: comparison with the monoclonal antibody abciximab. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(3):187–95.

Li X, Zhang S, Wang Z, Ji Q, Wang Q, Li X, et al. Platelet function and risk of bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndrome following tirofiban infusion. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1158.

Pitchford SC. Novel uses for anti-platelet agents as anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(7):987–1002.

Woodside DG, Vanderslice P. Cell adhesion antagonists: therapeutic potential in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BioDrugs. 2008;22(2):85–100.

Totani L, Evangelista V. Platelet–leukocyte interactions in cardiovascular disease and beyond. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(12):2357–61.

Benton AS, Kumar N, Lerner J, Wiles AA, Foerster M, Teach SJ, et al. Airway platelet activation is associated with airway eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. J Investig Med. 2010;58(8):987–90.

Clemetson KJ, Clemetson JM, Proudfoot AE, Power CA, Baggiolini M, Wells TN. Functional expression of CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CXCR4 chemokine receptors on human platelets. Blood. 2000;96(13):4046–54.

Semple JW, Freedman J. Platelets and innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(4):499–511.

Cognasse F, Nguyen KA, Damien P, McNicol A, Pozzetto B, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, et al. The inflammatory role of platelets via their TLRs and Siglec receptors. Front Immunol. 2015;6:83.

Hayashi N, Chihara J, Kobayashi Y, Kakazu T, Kurachi D, Yamamoto T, et al. Effect of platelet-activating factor and platelet factor 4 on eosinophil adhesion. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;104(Suppl 1(1):57–9.

Coyle AJ, Uchida D, Ackerman SJ, Mitzner W, Irvin CG. Role of cationic proteins in the airway. Hyperresponsiveness due to airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(5 Pt 2):63–71.

Gundel RH, Letts LG, Gleich GJ. Human eosinophil major basic protein induces airway constriction and airway hyperresponsiveness in primates. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(4):1470–3.

Mansour A, Bachelot-Loza C, Nesseler N, Gaussem P, Gouin-Thibault I. P2Y12 inhibition beyond thrombosis: effects on inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1931.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant, funded by a Grant from the Ministry and Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI16C0992).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this section.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SH., Trinh, H.K.T., Park, HS. et al. The blocking effect of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in the mouse model of asthma. Clin Mol Allergy 19, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12948-021-00149-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12948-021-00149-6