Abstract

Background

Many free-form-text referral requisitions for transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) provide insufficient information to adequately evaluate their adherence to Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC). We developed a structured referral requisition algorithm based on requisition deficiencies identified retrospectively in a derivation cohort of 1303 TTE referrals and evaluated the performance of the algorithm in a consecutive series of cardiology outpatient referrals.

Methods

The validation cohort comprised 286 consecutive TTE outpatient cardiology referrals over a 2-week period. The relevant AUC indication was identified from information extracted from the free-form-text requisition. The structured referral algorithm was applied prospectively to the same cohort using information from the free-form-text requisition, electronic medical record and ordering clinicians. Referrals were classified as appropriate, uncertain, non-adherent (inappropriate) or unclassifiable based on the American College of Cardiology Foundation 2011 AUC.

Results

Only 28.7 % of free-form-text requisitions provided adequate information to identify the relevant AUC indication, as compared to 94.4 % of referrals using the structured referral algorithm (p < 0.001). The structured algorithm improved identification in the AUC categories of general evaluation of cardiac structure/function (100 % vs. 43.0 %, p < 0.001); valvular function (100 % vs. 23.0 %, p < 0.001); hypertension, heart failure or cardiomyopathy (100 % vs. 20.3 %, p < 0.001); and adult congenital heart disease (100 % vs. 0 %, p < 0.001). By applying the algorithm, the number of identifiable non-adherent studies increased from 2.6 to 10.4 % (p <0.001).

Conclusions

Use of a structured TTE referral algorithm, as opposed to a free-form-text requisition, allowed the vast majority of referrals to be monitored for AUC adherence and facilitated the identification of potentially inappropriate referrals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The last 15 years have seen significant increases in health care expenditures leading to concerns about the sustainability of such growth [1, 2]. Cardiac diagnostic imaging represents a large component of the increase in health care expenditures, and the use of echocardiography, in particular, continues to rise [2–5]. There have been significant recent efforts to ensure that the use of diagnostic imaging is clinically indicated and of value. The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) Task Force has developed guidelines for the appropriate use of cardiac diagnostic services [6–9]. The first set of Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) for echocardiography were published in 2007 [9] and later updated in 2011 [6]. These criteria have been incorporated into educational efforts directed at physicians and patients in an attempt to limit unnecessary tests, treatments and procedures, such as the Choosing Wisely campaign, introduced in the United States in 2012 and in Canada in 2014 [10]. While the rate of increase in echocardiography use has slowed in recent years in association with the development of AUC and a reduction in reimbursement for echocardiography, the proportion of US Medicare beneficiaries receiving echocardiography services in 2011 exceeded those in 2007 when the AUC guidelines were published, and the average number of echocardiography studies per recipient per annum has continued to rise [4, 11]. It is estimated that approximately $750 billion of health care spending per year in the United States is wasted, with overuse of services beyond evidence-established levels playing a significant role [12].

Implementing AUC in echocardiography can have a direct clinical impact as appropriate studies are more likely to reveal new and major findings and are more likely to result in a patient care intervention [13]. Unfortunately ~10 % of transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) referrals are inappropriate or non-adherent to AUC [13, 14]. The prevalence of non-adherent referrals tends to be greater in outpatients [14–17], community settings [18] and non-specialist referrals [15, 19]; however inappropriate referrals have been reported in all clinical settings [13–20]. Therefore, adherence to AUC is important for cost containment, effective resource utilization and best practice clinical medicine.

Although the clinician orders the echocardiogram, the onus for the application of AUC has in part become the responsibility of the echocardiography laboratory. Demonstration of AUC monitoring and adherence is a requirement for the accreditation of echocardiography laboratories by government insurers, provincial regulatory bodies and international accreditation organizations such as the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC) [21, 22]. Unfortunately, monitoring adherence to AUC can be challenging. Clinicians usually request echocardiograms by completing free-form-text requisitions, whether in an electronic or paper format. In a recent study at our institution, of 1303 consecutive TTE referrals, more than 26 % of requisitions did not provide enough information to determine if the referral met AUC [17]. Further, 41 % of requisitions from cardiologists provided insufficient information [17]. Banihashemi and colleagues concluded that structured requisition formats that required referring physicians to provide AUC-relevant information were needed to facilitate the monitoring and application of AUC in the echocardiography laboratory.

Using information from this study [17], we designed a structured TTE referral requisition algorithm with mandatory fields that included the most common inadequacies identified, along with components of the ACCF 2011 AUC. The objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of the structured TTE referral algorithm compared to the standard free-form text referral requisition to evaluate AUC adherence in a consecutive series of cardiology outpatient referrals over a 2 week period.

Methods

Echocardiography laboratory

The University of Ottawa Heart Institute (UOHI) echocardiography laboratory provides outpatient and inpatient echocardiography services for both community and hospital based primary care physicians and specialists and is staffed by seven full-time Level 3 echocardiographers. The laboratory is accredited by IAC and has an annual TTE volume of 18,934 studies (2015).

Structured requisition algorithm

In our previous study of 1303 consecutive echocardiogram requisitions, 26.2 % of requisitions contained inadequate information to determine whether the referral was adherent to AUC [17]. The vast majority of inadequate requisitions occurred within the AUC categories of (1) evaluation of cardiac structure and function, (2) evaluation of valvular function, (3) evaluation of hypertension, heart failure, or cardiomyopathy and (4) adult congenital heart disease. The inadequacy related primarily to a failure of the requisition to report on a change in clinical status, provide the date of a previous echocardiogram if one had been done, or report the type and/or severity of a known valve lesion.

Using this information, we developed a structured requisition algorithm with mandatory fields which included the most common inadequacies, along with components of the ACCF 2011 AUC (Fig 1). This was applied retrospectively to the initial derivation cohort of 1303 requisitions and was successful in classifying all but 6 requisitions based on AUC.

Study population

The utility of the newly-designed structured referral requisition algorithm relative to the standard free-form-text requisition was assessed by applying the structured referral requisition algorithm prospectively to a validation cohort of consecutive TTE referrals from our outpatient cardiology clinic over a 2-week period (n = 286).

Echocardiography requisition review protocol

The review protocol was divided into two sequential phases.

First, the 286 free-form-text referral requisitions were evaluated by two reviewers for appropriateness of indication using only information extracted from the referral requisition (see Appendix). Requisition information was matched to the relevant indication in the ACCF 2011 AUC and categorized as classifiable, if they provided adequate information to identify a specific AUC indication, or not classifiable. If the referral requisition was classifiable, it was further categorized as appropriate, uncertain or non-adherent (inappropriate) based on the ACCF 2011 AUC.

Second, the structured requisition algorithm was applied to the same 286 referral requisitions by the same two reviewers, with all of the mandatory fields populated by information known to the ordering clinician (either provided in the free-form-text requisition, taken from previous clinic notes within the electronic medical records, or acquired through direct contact with the ordering clinician when required). Each requisition was again categorized as classifiable or not using the ACCF 2011 AUC, and further categorized as appropriate, uncertain or non-adherent based on the ACCF 2011 AUC.

Identification of the relevant ACCF 2011 AUC indication during review of the free-form-text requisitions and application of the structured algorithm was performed by the consensus of two reviewers, and a third reviewer if consensus was not achieved.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the percent of referral requisitions that were classifiable using the free-form-text referral requisition and the structured requisition algorithm. The secondary outcome measure was the percent of echocardiograms found to be non-adherent to AUC using each approach. Comparisons were made using Fisher’s exact test, with statistical significance set at p <0.05.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 286 consecutive TTE referrals received over the 2-week period. Median age was 61 years old [46–73 inter-quartile range]. 57.3 % were male. Of the 286 TTE referrals, 4 referrals were excluded because the structured referral requisition algorithm could not be used as additional medical information was not available (n = 2), the request was cancelled (n = 1), or the patient did not provide consent for chart review (n = 1). Of the remaining 282 TTE referrals, 268 (95.0 %) were for an indication outlined in the ACCF 2011 AUC, as determined by a complete review of the referral requisition, electronic medical record and information from the referring physician.

In those patients with a TTE referral encompassed in the ACCF 2011 AUC, only 28.7 % (n = 77) of the free-form-text requisitions provided adequate information to classify the referral to a specific indication in the ACCF 2011 AUC (Table 1). In 71.3 % (n = 191) of TTE referrals, the free-form-text requisition was unclassifiable, containing insufficient information to identify the relevant ACCF 2011 AUC indication.

When the structured referral requisition algorithm was applied to the same 268 TTE referrals encompassed in the ACCF 2011 AUC, 94.4 % (n = 253) of requests were classifiable, a significant improvement from the 28.7 % classifiable requisitions achieved using the free-form-text requisition (p <0.001) (Table 1). The structured referral requisition algorithm performed well in patients with both a classifiable and non-classifiable free-form text referral requisition. In 191 patients with a non-classifiable free-form-text requisition, application of the structured requisition algorithm resulted in 96.9 % (n = 185) of referrals being classifiable. The structured requisition algorithm classified 88.3 % of referrals when the free-form text requisition was classifiable. TTE referrals for ACCF 2011 AUC indications that were unclassifiable by our structured requisition algorithm (n = 15) are shown in Table 2. Evaluation/re-evaluation of ventricular function following ACS accounted for 80 % of unclassifiable requisitions using our structured referral requisition algorithm.

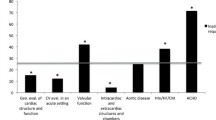

The prevalence of unclassifiable free-form-text requisitions in each ACCF 2011 AUC indication category is shown in Fig. 2. Over 50 % of free-form-text referral requisitions were unclassifiable in the categories of (1) adult congenital heart disease (100 % of requisitions unclassifiable), (2) evaluation of hypertension, heart failure or cardiomyopathy (79.7 % of requisitions unclassifiable), (3) evaluation of valvular function (77.0 % of requisitions unclassifiable), and (4) general evaluation of cardiac structure and function (57.0 % of requisitions unclassifiable). The structured algorithm improved the identification of the relevant ACCF 2011 AUC indication in all four categories such that 100 % were classifiable (p <0.001 for each) (Fig. 3).

Prevalence of classifiable TTE referrals using the free-form-text requisition (blue bars) and structured referral requisition algorithm (red bars) in the four AUC categories with the largest patient numbers. * p <0.001 for comparison of prevalences between the structured referral requisition algorithm and free-form-text requisition

The prevalence of appropriate, uncertain, non-adherent (inappropriate) and unclassifiable referrals using the free-form-text requisition and structured referral requisition algorithm are shown in Fig. 4. With application of the structured referral algorithm, the number of identifiable non-adherent studies based on the ACCF 2011 AUC increased from 2.6 to 10.4 % (p <0.001).

Discussion

The recently published ACCF 2011 AUC for echocardiography is a useful tool for physicians to guide their use of echocardiography, ensuring that echocardiography is used in clinical settings where it can provide the greatest diagnostic and prognostic value while also identifying scenarios where the diagnostic benefit is minimal. AUC have been adopted within the United States and other countries and serves as a quality measure during the accreditation of echocardiography laboratories by government and international organizations [21–23].

Unfortunately, most echocardiography laboratories use free-form-text referral requisitions, either in paper or electronic format, which limits the ability of an echocardiography laboratory to apply AUC to their referrals. In our study cohort, only 29 % of requisitions provided sufficient information to determine the specific AUC indication. Many physicians are not familiar with the specific information required for an AUC indication and as such may not provide the necessary information on the referral requisition for the echocardiography laboratory to determine the AUC indication and appropriateness of the referral. The most common deficiencies identified on free-form-text referrals relate to: 1) assessment of valvular heart disease, as the severity of the lesion, date of last assessment, and/or date of valve surgery (if applicable) must be provided to determine the AUC indication and appropriateness; 2) assessment of heart failure, as the date of last assessment and presence of any change in clinical condition must be provided; and 3) inadequate information about clinical status, which is applicable across multiple AUC indication categories [17]. Clearly, free-form-text referral requisitions provide a poor tool for evaluating the appropriateness of a referral.

To date, published studies evaluating the appropriateness of echocardiography have employed an extensive review of the patient’s medical record, including diagnostic requisitions, written or electronic patient charts, electronic databases and contact with the referring physicians [14, 15, 20, 24–30]. This retrospective process requires a significant investment of time and personnel by an echocardiography laboratory, is challenging without electronic access to the patient’s complete medical record, and is limited in scope since the echocardiography laboratory cannot evaluate all referrals in real-time, but rather only retrospectively sample a small portion of their volume for AUC adherence.

Our new structured referral requisition algorithm, when prospectively applied to consecutive referrals from our centre’s outpatient cardiology clinic, resulted in a dramatic reduction in unclassifiable TTE referral requisitions compared to the free-form-text requisition. The specific AUC indication could be identified in 94.4 % of TTE referrals using the structured requisition algorithm, compared to only 28.7 % using the free-form-text requisition. Importantly, the structured referral requisition algorithm improved our ability to identify non-adherent or potentially inappropriate studies; 10.4 % of requisitions were ultimately identified as non-adherent to AUC using the structured referral requisition algorithm, as compared to only 2.6 % of referrals using the free-form-text referral requisition.

Fifteen referrals (5.6 %) were not classifiable with our algorithm. This was primarily due to a failure of the algorithm to include fields for the assessment of ventricular function following an acute coronary syndrome (n = 12) and the assessment of aortopathy (n = 2). We used strict criteria and deemed a referral request unclassifiable if the reason for the referral did not clearly fall within the listed mandatory fields of our structured algorithm. While our algorithm does not specifically address ventricular function following an acute coronary syndrome, it is conceivable and likely that many physicians would describe a recent acute coronary syndrome as a recent change in clinical status and/or cardiac symptoms/signs. This would fulfill an indication field in the structured referral requisition algorithm and make the requisition classifiable, resulting in an even lower rate of unclassifiable requisitions than we have reported using our strict methodology. Nevertheless, with a further clarification and modification of the structured referral algorithm to address these two issues, all but one requisition would be classifiable.

The vast majority of echocardiography laboratories use free-form-text referral requisitions, although the requisition format may differ and may include a limited number of mandatory fields. This could impact on the prevalence of classifiable requisitions and lead to a prevalence of classifiable requisitions that differs from the 29 % observed in our cohort. However, our fully structured referral requisition algorithm avoids any requirement of the ordering physician to have knowledge of specific criteria for an AUC indication and thus has an inherent advantage over requisitions with more limited mandatory fields.

This study was conducted at a single tertiary-care academic centre, and it is possible that referral practices may differ at other institutions and could impact on the prevalence of unclassifiable requisitions. Although the structured referral algorithm was derived in a large unselected inpatient and outpatient referral population (n = 1303) with only 6 unclassifiable requisitions, the algorithm was prospectively tested in a cohort of consecutive TTE referrals from an outpatient cardiology clinic consisting of >30 cardiologists. In the 2010–2011 fiscal year in Ontario, Canada, 84.5 % of all echocardiograms were performed on an outpatient basis and approximately 60 % were referred from cardiologists, significantly more than any other specialty. Outpatient referrals from cardiologists have the highest rate of unclassifiable requisitions and therefore provide a suitable population to evaluate our structured referral algorithm [17]. However, caution should be taken in applying these results to other patient populations, specifically inpatients or outpatient referrals from non-cardiology practices, until these populations are more formally evaluated.

The ordering physician completed the free-form-text referral requisition; however, completion of the structured referral requisition algorithm was performed by study reviewers rather than the ordering physicians themselves. This was required to avoid introducing bias to the information provided by an ordering physician on subsequent free-form-text referral requisition submissions. While completion of the structured referral requisition algorithm by ordering physicians rather than study reviewers might affect the observed performance of our structured referral requisition algorithm, we believe the impact is likely small. First, reviewers only used information from the initial free-form-text referral requisitions, the referring physician’s notes or direct contact with the referring physician when populating the mandatory fields of the structured algorithm, information readily known to the ordering physician. Second, the questions in the structured algorithm are straightforward and minimize any ambiguity in interpretation. Third, referral requests were deemed unclassifiable by reviewers if the reason for the referral did not clearly fall within the listed mandatory fields. We believe this approach helped to eliminate any potential bias in favour of the structured referral algorithm. Nevertheless, performance of the structured referral requisition algorithm when completed by the ordering physician should be confirmed in a prospective study.

Our new structured TTE requisition shows promise in its ability to classify requisitions based on ACCF 2011 AUC that were unclassifiable using our standard free-form-text referral form. The new structured referral algorithm is relatively simple to fill out, and could be even further simplified using an electronic format in which the defaults for each question could be set to “not applicable” and only the question that applies would require further completion. Further, an electronic requisition could be programmed not to let an ordering physician submit a requisition if insufficient information is provided, or identify unclassifiable or non-adherent requisitions for further review between the referring physician and echocardiography laboratory, serving as a constraint or stop function.

The benefits of our structured referral requisition algorithm to classify previously unclassifiable requisitions are multiple. Firstly, the algorithm facilitates the process of real-time evaluation of appropriateness at the time of referral. Secondly, studies identified as non-adherent to AUC could be postponed in advance for review and cancelled if warranted, reducing both echocardiography laboratory costs and wait times. Thirdly, such a structured referral requisition algorithm would provide an opportunity for physician education as to the reason for the cancellation/postponement. Educational intervention has been demonstrated to reduce both the number of inappropriate outpatient transthoracic echocardiograms ordered by cardiology physicians-in-training [31] as well as the number of inappropriate echocardiograms on an inpatient medical service [29], and another study is ongoing looking at the benefit of a similar intervention in a more general population of physicians ordering echocardiograms [32]. If a submitted requisition is flagged as being non-adherent, further discussion with the echocardiography laboratory as needed could explain the rationale for the cancellation/postponement or conclude that the indication is actually appropriate after more information is provided. If it is found that the majority of these previously unclassifiable requisitions are in fact appropriate, then it may suggest that the main limiting factor in echocardiogram wait-times is not inappropriate referrals as some have argued [33], but rather resource availability. Correctly classifying the vast majority of referral requisitions using the structured referral requisition would provide transparency to the process of TTE referral that has yet to be achieved. It is our hope that with further investigation into different referral populations, the application of this structured referral requisition will allow echocardiography labs, accreditation organizations and government to better streamline the TTE referral process and optimize resource allocation.

Conclusion

In a consecutive cohort of TTE referrals from an outpatient cardiology clinic, free-form-text referral requisitions provided adequate information to determine AUC adherence in only 28.7 % of referrals. In contrast, use of a structured referral requisition algorithm with mandatory fields allowed AUC adherence to be determined in 94.4 % of TTE referrals. Importantly, the structured referral requisition algorithm improved our ability to identify non-adherent TTE referrals compared to a free-form-text referral requisition. Application of a structured TTE referral algorithm by an echocardiography laboratory has the potential to provide real-time monitoring of AUC adherence.

Abbreviations

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AUC, appropriate use criteria; IAC, Intersocietal Accreditation Commission; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; UOHI, University of Ottawa Heart Institute

References

Bailey SA, Mosteanu I, Tietjen PA, et al. The use of transthoracic echocardiography and adherence to appropriate use criteria at a regional hospital. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:1015–22. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2012.05.014.

Pearlman AS, Ryan T, Picard MH, et al. Evolving trends in the use of echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2283–91. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.048.

Blecker S, Bhatia RS, You JJ, et al. Temporal trends in the utilization of echocardiography in Ontario, 2001 to 2009. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:515–22. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.10.026.

Virnig BA, Shippee ND, O'Donnell B, Zeglin J, Parashuram S. Trends in the Use of Echocardiography, 2007 to 2011. Echocardiography Trends. Data Points #20 (prepared by the University of Minnesota DEcIDE Center, under Contract No. HHSA290201000131). Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 14-EHC034-EF.

Fonseca R, Otahal P, Wiggins N, Marwick TH. Growth and geographical variation in the use of cardiac imaging in Australia. Intern Med J. 2015;45:1115–27. doi:10.1111/imj.12867.

Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:229–67. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2010.12.008.

Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 Appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1864–94. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.005.

Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, et al. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 Multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:380–406. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.009.

Douglas PS, Khandheria B, Stainback RF, et al. ACCF/ASE/ACEP/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2007 Appropriateness criteria for transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria working group, American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:787–805.

Levinson Y, Huynh T. Engaging physicians and patients in conversations about unnecessary tests and procedures: Choosing Wisely Canada. CMAJ. 2014;186:325–6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.131674.

Levin DC, Rao VM, Parker L, Frangos AJ, Sunshine JH. Bending the curve: the recent marked slowdown in growth of noninvasive diagnostic imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W25–9. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.4835.

Institute of Medicine. Best Care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2013. doi:10.17226/13444.

Alqarqaz M, Koneru J, Mahan M, et al. Applicability, limitations and downstream impact of echocardiography utilization based on the appropriateness use criteria for transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:1951–8. doi:10.1007/s10554-012-0008-6.

Patil HR, Coggins TR, Kusnetzky LL, Main ML. Evaluation of appropriate use of transthoracic echocardiography in 1,820 consecutive patients using the 2011 revised appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1814–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.025.

Ward RP, Mansour IN, Lemieux N, Gera N, Mehta R, Lang RM. Prospective evaluation of the clinical application of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Society of Echocardiography Appropriateness Criteria for transthoracic echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:663–71. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.07.004.

Matulevicius SA, Rohatgi A, Das SR, Price AL, DeLuna A, Remold SC. Appropriate use and clinical impact of transthoracic echocardiography. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1600–7. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8972.

Banihashemi B, Maftoon K, Chow BJ, et al. Limitations of free-form-text diagnostic requisitions as a tool for evaluating adherence to appropriate use criteria for transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2015;13:4. doi:10.1186/1476-7120-13-4.

Ballo P, Bandini F, Capecchi I, et al. Application of 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Society of Echocardiography appropriate use criteria in hospitalized patients referred for transthoracic echocardiography in a community setting. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:589–98. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2012.03.006.

Chiriac A, Kadkhodayan A, Pislaru SV, et al. Clinical importance of transthoracic echocardiography with direct input from treating physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:195–204. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2015.11.009.

Ward RP, Krauss D, Mansour IN, et al. Comparison of the clinical application of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Society of Echocardiography Appropriateness Criteria for outpatient transthoracic echocardiography in academic and community practice settings. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1375–81. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2009.08.005.

Sanfilippo AJ, Chan KL, Hughes W, et al. Standards for provision and accreditation of echocardiography in Ontario. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:396–8. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.024.

Intersocietal Accreditation Commission. Echocardiography facility accreditation. Available at: www.intersocietal.org/echo. Accessed 5 April 2015.

Gurzun MM, Ionescu A. Appropriateness of use criteria for transthoracic echocardiography: are they relevant outside the USA? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:450–5. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jet186.

Martin NM, Picard MH. Use and appropriateness of transthoracic echocardiography in an academic medical center: a pilot observational study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:48–52. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2008.10.003.

Kirkpatrick JN, Ky B, Rahmouni HW, et al. Application of appropriateness criteria in outpatient transthoracic echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:53–9. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2008.10.020.

Willens HJ, Gómez-Marín O, Heldman A, et al. Adherence to appropriateness criteria for transthoracic echocardiography: comparisons between a regional department of Veterans Affairs health care system and academic practice and between physicians and mid-level providers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:793–9. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2009.04.018.

Rao G, Sajnani N, Kusnetzky LL, Main ML. Appropriate use of transthoracic echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1640–2. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.026.

Parikh PB, Asheld J, Kort S. Does the revised appropriate use criteria for echocardiography represent an improvement over the initial criteria? A comparison between the 2011 and the 2007 appropriateness use criteria for echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:228–33. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2011.09.017.

Bhatia RS, Milford CE, Picard MH, Weiner RB. An educational intervention reduces the rate of inappropriate echocardiograms on an inpatient medical service. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:545–55. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.01.010.

Bhatia RS, Carne DM, Picard MH, Weiner RB. Comparison of the 2007 and 2011 appropriate use criteria for transthoracic echocardiography in various clinical settings. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:1162–9. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2012.07.018.

Bhatia RS, Dudzinksi DM, Malhotra R, et al. Educational intervention to reduce outpatient inappropriate echocardiograms: a randomized control trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:857–66. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.04.014.

Bhatia RS, Ivers N, Yin CX, et al. Design and methods of the Echo WISELY (Will Inappropriate Scenarios for Echocardiography Lessen SignificantlY) study: An investigator-blinded randomized controlled trial of education and feedback intervention to reduce inappropriate echocardiograms. Am Heart J. 2015;170:202–9. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.022.

Iglehart JK. Health insurers and medical-imaging policy--a work in progress. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1030–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr0808703.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There are no sources of funding.

Availability of data and materials

Available data is presented in the main paper.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: SP, BB, IGB. Acquisition of data: SP, JGA, BB, KM, IGB. Analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis: SP, JGA, IGB. Drafting of the manuscript: SP, JGA, IGB. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SP, JGA, BJC, GD, IGB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (Protocol 20150464).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Promislow, S., Abunassar, J.G., Banihashemi, B. et al. Impact of a structured referral algorithm on the ability to monitor adherence to appropriate use criteria for transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 14, 31 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12947-016-0075-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12947-016-0075-2