Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown a correlation between depression and obesity, as well as between depression and the Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP). However, there is limited research on the association between visceral obesity and depression, as well as the potential mediating role of AIP in this relationship.

Methods

This study included 13,123 participants from the 2005–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Visceral obesity was measured with the Body Roundness Index (BRI), while depression was evaluated with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. The AIP served as a marker for lipid disorders. To investigate the association between the BRI and depression, multivariate logistic regressions, restricted cubic spline models, subgroup analyses, and interaction tests were used. Additionally, a mediation analysis was conducted to explore the role of AIP in mediating the effect of BRI on depression.

Results

There was a positive linear correlation between the BRI and depression. After controlling for all covariates, individuals in the highest BRI (Q4) group had an OR of 1.42 for depression (95% CI: 1.12–1.82) in comparison with individuals in the lowest BRI (Q1) group. Moreover, the AIP partially mediated the association between the BRI and depression, accounting for approximately 8.64% (95% CI: 2.04-16.00%) of the total effect.

Conclusion

The BRI was positively associated with depression, with the AIP playing a mediating role. This study provides a novel perspective on the mechanism that connects visceral obesity to depression. Managing visceral fat and monitoring AIP levels may contribute to alleviating depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent psychological disorder marked by feelings of sadness and diminished interest in activities [1, 2]. This condition damages individuals’ physical, mental, and social well-being, exacerbating the burden on public health [3]. Previous researches have shown a greater prevalence of depression among obese individuals [4]. However, Body Mass Index (BMI) was deemed as the major indicator to assess obesity in these studies. While BMI can effectively evaluate the relationship between overall obesity and diseases [5], it does not effectively reflect the impact of fat distribution on depression. Additionally, waist circumference (WC), an indicator used to assess abdominal obesity, cannot accurately differentiate between subcutaneous fat and visceral fat [6]. Visceral fat is considered more harmful than fat in other parts of the body, and even individuals with a normal BMI or WC may have a significant accumulation of visceral fat [7]. Thomas and his team introduced the Body Roundness Index (BRI) through mathematical modeling to assess visceral fat levels [8]. Compared to WC, the BRI offers a more accurate depiction of visceral fat distribution [8]. Moreover, the BRI has been proven to be a convenient, fast, and cost-efficient alternative to approaches requiring X-ray scans for visceral fat evaluation [9]. Previous studies have shown correlations between the BRI and various health conditions, such as diabetes [10], and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [11]. However, there is limited research on the relationship between the BRI and depression.

Previous studies have identified dyslipidemia as a contributing factor to the occurrence and progression of depression [12, 13]. A newly recognized lipid marker named the atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) is used to evaluate lipid metabolism disorders [14]. The AIP was originally used for the prediction of atherosclerosis risk [15]. However, recent studies have shown that there was an association between the AIP and the incidence of depression [16,17,18]. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated strong correlations between visceral obesity and dyslipidemia [19, 20]. Considering that lipids and AIP can serve as indicators for drug intervention, and can help differentiate the risk of depression among patients with visceral obesity, investigating the mediating effect of AIP on the relationship between BRI and depression is of significant importance. Therefore, in this study, we utilized a large dataset from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to investigate the relationship between BRI and depression. Additionally, we hypothesized that BRI could be associated with AIP, and that AIP might serve as a mediator between BRI and depression. To reveal this mediating effect, a two-step mediation analysis was employed.

Methods

Data source and participants selection

NHANES is a project of the National Center for Health Statistics that provides a thorough and continuous assessment of the health and nutrition of the American population. A sophisticated stratified sampling methodology was applied in the NHANES to enhance the accuracy and reliability of representative samples. Comprehensive data, including socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, dietary habits, and health-related information, are collected by trained personnel. All participants must provide signed consent forms in order to participate in the study.

This study utilized data from the NHANES cycles from 2005 to 2018, aligning with the availability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) from 2005 to 2018. The present investigation included a total of 70,190 participants from these cycles. In the analysis, 30,441 participants under the age of 20 years were excluded. Additionally, 771 pregnant individuals were excluded due to alterations in blood lipid profiles, WC, and depression status. Those with missing PHQ-9 data (n = 5,543), BRI data (n = 1,119), and AIP data (n = 17,483) were also omitted. Individuals without information on covariates such as alcohol consumption status, smoking status, poverty income ratio (PIR), marital status, and education level were excluded (n = 1,770) (Fig. 1). Ultimately, this study included 13,123 individuals.

Ascertainment of depression

The PHQ-9 [21] is a questionnaire widely used for screening depression. It consists of a total of 9 questions, graded on criteria from 0 to 3, resulting in a cumulative score scale from 0 to 27. A total score of 10 or higher was indicative of the presence of depression [21]. This cut-off point is commonly used in epidemiological research for the identification of individuals with depression and has been validated through clinical assessment [21].

Ascertainment of the BRI

The model proposed by Thomas et al. was used to calculate the BRI [8]. This model incorporates two primary variables (height, and WC), to evaluate visceral fat content. A higher BRI indicates a greater accumulation of visceral fat. The specific mathematical formula for BRI calculation is as follows: 364.2-365.5 × (1-[WC (m)/2π]2/[0.5×height(m)]2)½. The BRI is categorized into four levels, ranging from low to high with the quartile intervals as follows: Q1 (1.19 ~ 3.82), Q2 (3.82 ~ 5.07), Q3 (5.07 ~ 6.67), and Q4 (6.67 ~ 19.00).

Ascertainment of the AIP

The calculation of the AIP is based on indicators of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglyceride (TG) levels in the blood. The specific mathematical formula for AIP calculation is as follows: log10 [TG (mmol/L)/HDL-C (mmol/L)] [14].

Covariates

In this study, the covariates included demographic characteristics (age, sex, and race), socioeconomic indicators (marital status, PIR, and education level), alcohol consumption status, smoking status, antidepressant use, and health conditions. Marital status was categorized as coupled (including married or living with a partner) and single/separated (including never married, separated, divorced, or widowed). Race was classified as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic White, other Hispanic (including Mexican American), or other. The participants’ education level was divided into three levels: less than high school, high school, and above high school. The PIR was grouped into three categories: < 1.30, 1.31 ~ 3.50, and > 3.50, with a higher PIR reflecting a better family economic status [22, 23]. Alcohol consumption condition was categorized into three groups: never drinkers (those who had consumed < 12 times in their lifetime), former drinkers (those who had consumed ≥ 12 times in a year but had not consumed any alcohol in the past year or did not consume alcohol in the last year but had consumed ≥ 12 times in their lifetime), and current drinkers (those who currently consumed at least one drink) [24, 25]. Detailed information on smoking status, diabetes status, CVD status, chronic kidney disease (CKD) status, cancer status, and antidepressant use is provided in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

To enhance the representativeness of the research results, we followed the NHANES official recommended weighted procedures to process the data in this study. Based on the PHQ-9 scores of the participants, this study classified them into two groups: depression and non-depression [21]. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student t tests to compare the continuous variables and chi-square tests to compare the categorical variables between the two groups. To explore the relationship between the BRI and depression, weighted linear regression models (for continuous PHQ-9 scores) and logistic regression models (for depression) were used in the three statistical models to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and adjusted odds ratios (ORs). Model 1 served as a crude model with no adjustments of variables. Model 2 was adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age, sex, and race) [26]. Model 3 was more adjusted for the PIR, marital status, education level, alcohol consumption status, smoking status, CVD status, diabetes status, CKD status, cancer status, and antidepressant use. In these models, when the BRI was considered an ordered four-category variable, trend tests were also conducted. Additionally, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was conducted to determine whether the association between BRI and depression is linear. We also conducted subgroup analyses to assess the influence of the BRI on depression concerning several stratified covariates, including age (category), sex, PIR, education level, and disease status (diabetes, CVD, CKD, and cancer).

The two-step mediation analysis was used to evaluate the mediating effect of AIP. Firstly, a fully adjusted regression model was employed to investigate the impact of the BRI on AIP as well as the impact of the AIP on depression, aiming to ascertain the potential of the AIP to serve as a mediating factor between the BRI and depression. Subsequently, mediation analysis was conducted using the RMediation package to assess the indirect, direct, and overall effect of the BRI on depression mediated by the AIP [27]. After dividing the indirect effect by the total effect, the percentage of the mediating effect mediated by the AIP was determined. The 95% CI for the mediated proportion was estimated through nonparametric bootstrapping with 1000 iterations.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software (version 4.2.3). When the two-sided P value ≤ 0.05, it is considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic information

As shown in Table 1, this study comprised 13,123 individuals with a mean age of 47.51 ± 0.55 years. Of all these individuals, 1,085 (8.27%) were identified as having depression (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10). Females and individuals with a single/separated marital status exhibited a greater prevalence of depression. Moreover, individuals with depression tended to have lower education and income levels. Furthermore, the BRI of individuals with depression was higher than those without depression (P < 0.001).

Relationship between the BRI and depression

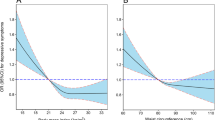

As shown in Table 2, the BRI was positively correlated with the PHQ-9 score in both the crude model (β coefficients: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.16–0.23) and the fully adjusted model (β coefficients: 0.12, 95% CI: 0.08–0.16). A similar correlation between the BRI and depression was also observed. After adjusting for all covariates, the likelihood of depression increased by 7.0% for each unit increase in the BRI (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 1.04–1.10). Furthermore, this study revealed that individuals in the highest BRI (Q4) group had an OR of 1.42 for depression (95% CI: 1.12–1.82) in comparison with participants in the lowest BRI (Q1) group. RCS analyses indicated a linear association between the BRI and depression, as well as between the BRI and PHQ-9 score (Fig. 2).

(A) The dose–response relationship between BRI and PHQ-9 score; (B) The dose–response relationship between BRI and depression. The associations were adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, marital status, poverty income ratio, smoking status, alcohol status, diabetes status, cardiovascular disease status, chronic kidney disease status, cancer status and antidepressant use

Subgroup analysis

To investigate the association between the BRI and depression across diverse populations stratified by age, sex, the PIR, education level, and disease status (diabetes, CVD, CKD, and cancer), subgroup analyses were performed. This study revealed a significant gender interaction effect between the BRI and depression (interaction P value < 0.05). Among females, each one-unit increase in the BRI corresponded to a 14.0% increase in the incidence of depression (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.11–1.18). However, other covariates, such as age and PIR, were not identified to have interactive effects on the association between depression and BRI (Table 3).

Mediation analysis

In the mediation analysis, the BRI, the AIP, and depression were considered the independent variable, mediator variable, and dependent variable, respectively. The mediation model and paths are shown in Fig. 3. The research findings demonstrated a noteworthy correlation between the BRI and AIP (β coefficients: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–34.42), as well as between the AIP and depression (β coefficients: 0.31, 95% CI: 0.11–2.72). Further analysis demonstrated a noteworthy indirect impact of the BRI on depression through the AIP, with an indirect effect size of 0.013 (P = 0.008). It suggests that the AIP partially mediated the association between the BRI and depression, accounting for approximately 8.64% (95% CI: 2.04-16.00%) of the total effect.

Discussion

This study revealed a positive association between BRI and depression, with a notably stronger association among females. Additionally, the mediation analysis revealed that the AIP partially mediated the association between the BRI and depression.

The current research represents one of the largest investigations to date in exploring the relationship between the BRI and depression, involving a representative cohort of 13,123 American adults from the NHANES. A previous cross-sectional study in the elderly population in China discovered a positive correlation between the BRI and depression [28], aligning with the results of this study. However, Lotfi et al.‘s study conducted among healthcare and administrative personnel in Iran did not reveal this association [29]. The difference in research findings between Lotfi’s study and ours can be explained by the following reasons. First, our study sample covered a broader range, including populations of different ages, and races. The mean age of individuals in our study is 47.51 years old, whereas Lotfi’s study reported a mean participant age of 36.6 years. Lotfi’s study involved a younger population, and age is an important covariate that may affect the association between BRI and depression. Second, this study used the PHQ-9 for depression screening, while Lotfi et al. used the HADS. However, in the general population, the PHQ-9 has shown higher levels of sensitivity and specificity, which is beneficial for identifying depression patients [30].

The interaction analysis revealed that there may be a certain interaction effect between the BRI and sex on depression, with the BRI having a greater impact on depression in females. Firstly, this may be because depression is more common among females. Another possible explanation is that sex differences lead to differences in hormone levels, consequently influencing the correlation between BRI and depression. For example, oestrogen has an impact on fat distribution [31] and the occurrence of depression [32]. Oestrogen is believed to regulate the distribution of fat, favouring the accumulation of subcutaneous fat rather than visceral fat [31]. Moreover, baseline levels and fluctuations in oestrogen are thought to increase the risk of depression in females [32], so the accumulation of visceral fat could be strongly linked to depression in females. In addition, there are other possible mechanisms that are worthy of further research.

The research findings indicate that the AIP partially mediates the correlation between visceral obesity (as determined by the BRI) and depression. This suggests that monitoring the AIP levels of patients with high BRIs is crucial. Previous researches have indicated a close relationship between lipid metabolism disorders and depression [12, 33]. Regulating the AIP, especially by increasing HDL-C levels and reducing TG levels, may help reduce the risk of depression in individuals with high BRIs.

Strengths and limitations

The study presented several advantages. Firstly, compared to methods such as X-ray and computed tomography, which require complex diagnostic equipment or invasive assessments of visceral fat, the BRI is simpler, more convenient, easier to implement, provides greater clinical utility, and has economic feasibility [8]. Secondly, this study utilized weighted NHANES national sample data, which can better reflect the relationship between the BRI and depression in American adults. Thirdly, we thoroughly reviewed previous literature, considered and controlled for various potential confounders that might influence the relationship between the BRI and depression, and employed multivariable regression models to derive more accurate conclusions. Fourthly, this study conducted an intermediary analysis to investigate the associations between lipid-related characteristics, visceral obesity, and depression.

This study also bears limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes establishing a causal link between the BRI and depression. Secondly, the study cannot account for all potential confounding factors, such as adverse childhood experiences and personality traits. These variables are related to visceral fat [34,35,36] and depression [37, 38], but the NHANES database lacks relevant variable records. Thirdly, the slightly low proportion of mediation by the AIP suggests that further research may be necessary to explore the mechanisms that underlie the association between the BRI and depression. Moreover, the study found interaction effects between gender and BRI on depression, suggesting the necessity for additional investigation.

Conclusion

The BRI was positively associated with depression, with the AIP playing a mediating role. This study provides a novel perspective on the mechanism that connects visceral obesity to depression. Managing visceral fat and monitoring AIP levels may contribute to alleviating depression.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- BRI:

-

Body Roundness Index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- AIP:

-

Atherogenic Index of Plasma

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

References

Malhi GS, Mann JJ, Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299–312.

Marx W, Penninx BWJH, Solmi M, Furukawa TA, Firth J, Carvalho AF, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:44.

Stecher C, Cloonan S, Domino ME. The Economics of Treatment for Depression. Annu Rev Public Health. 2023.

Treviño-Alvarez AM, Sánchez-Ruiz JA, Barrera FJ, Rodríguez-Bautista M, Romo-Nava F, McElroy SL, et al. Weight changes in adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2023;332:1–8.

He K, Pang T, Huang H. The relationship between depressive symptoms and BMI: 2005–2018 NHANES data. J Affect Disord. 2022;313:151–7.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Li C, Tsai J, Dhingra S, Balluz LS. Waist circumference, abdominal obesity, and depression among overweight and obese U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:130.

Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després J-P, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:715–25.

Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obes (Silver Spring). 2013;21:2264–71.

Gao W, Jin L, Li D, Zhang Y, Zhao W, Zhao Y, et al. The association between the body roundness index and the risk of colorectal cancer: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2023;22:53.

Wu L, Pu H, Zhang M, Hu H, Wan Q. Non-linear relationship between the body roundness index and incident type 2 diabetes in Japan: a secondary retrospective analysis. J Transl Med. 2022;20:110.

Zhang X, Ding L, Hu H, He H, Xiong Z, Zhu X. Associations of body-roundness index and Sarcopenia with Cardiovascular Disease among Middle-aged and older adults: findings from CHARLS. J Nutr Health Aging. 2023;27:953–9.

Huang T, Chen J. Cholesterol And Lipids In Depression: Stress, Hypothalamo-Pituitary‐Adrenocortical Axis, And Inflammation/Immunity. Advances in Clinical Chemistry [Internet]. Elsevier; 2005 [cited 2024 Mar 31]. pp. 81–105. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065242304390037.

Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP. Vascular risk factors and depression in later life: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:406–13.

Dobiásová M, Frohlich J. The plasma parameter log (TG/HDL-C) as an atherogenic index: correlation with lipoprotein particle size and esterification rate in apob-lipoprotein-depleted plasma (FER(HDL)). Clin Biochem. 2001;34:583–8.

Fernández-Macías JC, Ochoa-Martínez AC, Varela-Silva JA, Pérez-Maldonado IN. Atherogenic index of plasma: Novel Predictive Biomarker for Cardiovascular illnesses. Arch Med Res. 2019;50:285–94.

Ye Z, Huang W, Li J, Tang Y, Shao K, Xiong Y. Association between atherogenic index of plasma and depressive symptoms in US adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 to 2018. J Affect Disord. 2024;356:239–47.

Nunes SOV, Piccoli de Melo LG, Pizzo de Castro MR, Barbosa DS, Vargas HO, Berk M, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma and atherogenic coefficient are increased in major depression and bipolar disorder, especially when comorbid with tobacco use disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:55–62.

Zhang H, Zhang G, Fu J. Exploring the L-shaped relationship between Atherogenic Index of plasma and depression: results from NHANES 2005–2018. J Affect Disord. 2024;359:133–9.

Després JP. Visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia: contribution of endurance exercise training to the treatment of the plurimetabolic syndrome. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1997;25:271–300.

Salmón-Gómez L, Catalán V, Frühbeck G, Gómez-Ambrosi J. Relevance of body composition in phenotyping the obesities. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2023;24:809–23.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kruszon-Moran D, Dohrmann SM et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat 2. 2013;1–24.

Bao W, Liu B, Simonsen DW, Lehmler H-J. Association between exposure to pyrethroid insecticides and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the General US Adult Population. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:367–74.

Hicks CW, Wang D, Matsushita K, Windham BG, Selvin E. Peripheral neuropathy and all-cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in U.S. adults: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:167–74.

Rattan P, Penrice DD, Ahn JC, Ferrer A, Patnaik M, Shah VH, et al. Inverse Association of Telomere length with Liver Disease and Mortality in the US Population. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:399–410.

Wan Z, Guo J, Pan A, Chen C, Liu L, Liu G. Association of serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;44:350–7.

Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43:692–700.

Wang Y, Zhang X, Li Y, Gui J, Mei Y, Yang X, et al. Predicting depressive symptom by cardiometabolic indicators in mid-aged and older adults in China: a population-based cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1153316.

Lotfi K, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A, Saneei P, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. A body shape index and body roundness index in relation to anxiety, Depression, and psychological distress in adults. Front Nutr. 2022;9:843155.

Negeri ZF, Levis B, Sun Y, He C, Krishnan A, Wu Y, et al. Accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for screening to detect major depression: updated systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;375:n2183.

Steiner BM, Berry DC. The Regulation of Adipose Tissue Health by Estrogens. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 31];13. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.889923/full.

Barth C, Crestol A, de Lange A-MG, Galea LAM. Sex steroids and the female brain across the lifespan: insights into risk of depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:926–41.

Guillemot-Legris O, Muccioli GG. Obesity-Induced Neuroinflammation: beyond the Hypothalamus. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:237–53.

Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:544–54.

Jiang D-X, Huang T-Y, Chen J, Xiao W-C, Shan R, Liu Z. The association of personality traits with childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;340:598–606.

Gerlach G, Herpertz S, Loeber S. Personality traits and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2015;16:32–63.

Zheng X, Cui Y, Xue Y, Shi L, Guo Y, Dong F, et al. Adverse childhood experiences in depression and the mediating role of multimorbidity in mid-late life: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:217–24.

Klein DN, Kotov R, Bufferd SJ. Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:269–95.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the implementers and participants of the NHANES project, whose assistance has led to the completion of this study.

Funding

This study did not receive funding support from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.-S.Z. and H.-K.Z. contributed in the data curation; G.-S.Z., Y.-F.Z. and J.F. in the formal analysis; G.-S.Z., Y.-F.Z. and J.F. in project conceiving, designing, and initiating; G.-S.Z. and H.-K.Z. in project administration; Y.-F.Z. and J.F. in supervision; G.-S.Z. in writing of the original draft; G.-S.Z., H.-K.Z., J.F. and Y.-F.Z. in writing of the review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a publicly available database, implemented with the approval of the National Center for Health Statistics review board. All participants provided written informed consent when participating in the survey. Therefore, this study is exempt from the requirements of ethical review and approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Zhang, H., Fu, J. et al. Atherogenic Index of Plasma as a Mediator in the association between Body Roundness Index and Depression: insights from NHANES 2005–2018. Lipids Health Dis 23, 183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02177-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02177-y