Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) exerts an intense impact on host lipid metabolism. Hence the aim of present study is to determine metabolic derangement that occurred in subjects suffering from hepatitis B patients.

Methods

The fasting blood samples were collected from hepatitis B patients (n = 50) attended in Taluka hospital TandoAdam, Sindh with age and gender matched controls (n = 50). Serum lipid profile and fatty acid (FA) composition were analyzed by micro-lab and gas chromatography.

Results

The hepatitis B patients have significantly lower level (p < 0.01) of lipid profile including total cholesterol (TC), triacylglyceride (TAG), high density lipoprotein-C (HDL-C) very low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (VLDL-C), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), and total lipid (TL) in comparison to controls, indicating hypolipidemia in patients. The result of total FA composition of HBV patients in comparison to controls reveal that myristic, palmitic, docosahexaenoic acids were significantly (p < 0.05) higher, while linoleic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic acids were lower in HBV patients in comparison to controls. The elongase, ∆5 and ∆6-desaturase enzymes activities were found lower, while ∆9-desaturase activity was higher in hepatitis B patients as compared to controls, which indicates the impaired lipid metabolism.

Conclusion

The serum saturated fatty acid (SFA) and monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) were increased while polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) was reduced in both total and free form in hepatitis B patients due to altered activities of enzyme desaturases with impaired PUFA metabolism and non-enzymatic oxidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis B is a substantial health concern disturbing people all around the world. The World Health Organization in 2015 estimated that 240 million people have been already suffering in the chronic stage of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection Worldwide, and 780,000 people lost their lives every year from hepatitis B [1]. Pakistan is having high dominance of HBV infection in all provinces. Approximately 9 million people are infected with HBV and its infection is growing evermore in our country day by day [2].

Ress et al., in 2016 [3] has reported that diseases agents interfere with the lipid metabolism by altering the liver function, which results in gathering of lipid drops in the liver cells that may cause in hepatic steatosis which results in defective secretion of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and alteration in the beta-oxidation. The fatty acid (FA) synthesis pathways are also affected by increased production of non-esterified FA, which is a major causing factor of fatty liver patients with HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [4]. Over the past decade, HBV and altered plasma metabolites and their impaired functions become the subject of interest for biomedical researchers. The liver is an essential regulating organ plays a critical role by modulating exogenous and endogenous lipid metabolism. It is involved in the generating and reprocessing of lipid metabolites including lipoproteins such as high density lipoprotein-C (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein-C (LDL-C), total plasma cholesterol and triacylglyceride (TAG). The circulating level of those metabolites in plasma depends upon the functional capability of liver cells and tissues. Chronic HBV infection is directly affecting the functional capability of liver cells [5]. Mild to severe liver disrupting reasons such as chronic HBV infection could probably affect directly or indirectly on the levels of these lipid substrates in the plasma [6].

The fatty acids analysis in serum provided direct evidence on the fatty acids synthesis in the liver [7]. The saturated fatty acid (SFA), such as palmitic acid and yields of its conversion in to monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) from the n-3 and n-6 families are connected through the metabolic activity of the liver [8]. Unger., in 2003 [9] has reported that free fatty acids (FFAs) are important mediators of lipotoxicity, they act as possible cellular toxins and leads to the lipid over-accumulation. When lipids are over-accumulated in non-adipose tissue, they may enter into non-oxidative deleterious pathways leading to cell injury and death. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the FFA in serum provide an ancillary source of evidence on the synthesis of FA in the liver [10].

This information proposes that a relationship between metabolic alterations and HBV infection. Hence, the present study was undertaken to explore the changes and metabolic derangement in lipid metabolism of total lipid (TL), total cholesterol (TC), TAG, HDL–C, LDL–C, VLDL–C, total fatty acid (TFA) and FFA as reflected in the circulation of hepatitis B patients to compare this with that of healthy controls.

Methods

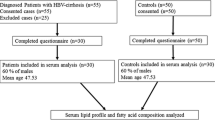

Hepatitis B is a severe form of viral hepatitis transmitted in infected blood, causing fever, debility, and jaundice. The patients attended in Taluka hospital TandoAdam with fever, headache, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain and jaundice, their blood samples were subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) test. The HBV positive patients with elevated ALT levels were further confirmed by Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) HBV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) active replication (> 1.30–8.23 log IU/mL reactive and < 1.3 log IU/mL non-reactive) and enrolled in the study. Age and gender matched controls with the negative history of hepatitis B (confirmed by ELISA test) were also included in the study. The flow chart of study is presented in Fig. 1.

Sample collection and analysis

5 ml intravenous blood samples from HBV-positive patients and healthy controls (HBV-negative) were collected after 14 h overnight fasting. Serum was separated and stored at − 40 °C until analyzed for lipid profile and fatty acids by micro-lab 300 and gas chromatograph 8700 (Perkin–Elmer Ltd). FAs were analyzed as TFA and FFA. TFA, as well as FFA contents of the samples, were analyzed as per reported method [11]. Peaks were identified by authentic standards supplied by Fluka Chemika (Buchs, Switzerland). Analytical grade reagents and solvents were utilized throughout the study. The peak area was used to calculate FA composition as a relative ratio of the total FA.

The desaturase and elongase enzymes activities calculation

Desaturase and elongase activities were calculated as the ratio of product to the precursor of an individual FA in serum (g/100 g) according to the following expression:

Δ-9 desaturase (D9D) = 16:1/16:0 and 18:1/18:0;

Δ-6 desaturase (D6D) = 18:3/18:2.

Δ-5 desaturase (D5D) = 20:4/20:3; and elongase = 18:0/16:0. [12].

Model for end stage liver disease (MELD) calculation

MELD score was calculated by using the base line characteristics through “Online UNOS MELD calculator” [13]:

Statistical analysis

The data values are stated as mean with standard deviation. Student’s t-test /the Mann- Whitney U test was used for the relationship among the groups (controls vs. patients) with SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Independent relationship of individual factor with Hepatitis B patients was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analysis by the SAS statistical software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Odds ratios and confidence intervals (CI) at 95% were designed to evaluate the risk factor for quartiles and continuous variables. Logistic-regression model was used to perform trends within each group. Quartile cut points with the lowest quartile were used as a reference to determine the division of the FA contents. The significant variations were observed when the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

For the study, eighty hepatitis B patients consented; thirty patients were excluded by fulfilling criteria for exclusion as they were suffering from hepatitis co-infection, hypertension, diabetes, malnutrition, malabsorption, hyperthyroidism, renal failure, malignancy and immunoglobulin disorders. The blood specimens were also collected from fifty patients and fifty age and gender matched controls. The mean ± SD age of cases and controls was 31.7 ± 11.01 (age range17–60 years). Among the cases 53% were male.

Base line characteristics

The base characteristics were collected during filling of the questionnaire and laboratory results of patients recorded. Table 1 shows the base line characteristics of hepatitis B patients including; random blood sugar, total protein, serum albumin, creatinine, total bilirubin, urea with in the normal limits and ALT level was increased in hepatitis B patients. The quartiles were calculated for base line characteristics of hepatitis B patients which reveals that cut-off for the first quartile is the 25th percentile, second quartile is the 50th percentile, which is the median and third quartile is the 75th percentile. It is evident that from the 25th percentile score majority of hepatitis B patients have serum albumin ≥3.4 g/dl. In addition score of 75th percentile indicated that most of hepatitis B patients possessed serum creatinine and total bilirubin below 1.0 mg/dl.

MELD score of hepatitis B patients

The MELD score was used to estimate relative disease severity and likely survival of patients awaiting liver transplantation. The hepatitis B patients MELD scores was 20 points showed 6.0% estimated 3 months mortality risk (Table 2).

Lipid profile

The hepatitis B patients have significantly lower serum level (p < 0.001) of lipid profile including TC, VLDL-C, LDL-C, HDL-C, TAG and TL in comparison to controls (Table 3).

Fatty acid composition

The results of hepatitis B patients for serum TFA composition in comparison to controls revealed that myristic, palmitic, stearic, lignoceric, palmitoleic, oleic, docosenoic, docosahexaenoic acids were higher in hepatitis B patients and a significant difference was observed in myristic, palmitic, eicosapentaenoic acids. The linoleic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic acids were significantly lower (< 0.05) in hepatitis B patients in comparison to control subjects. The α-linolenic was decreased but not significant. The PUFA: SFA ratio was reduced in HBV patients as compared to healthy subjects (Table 4).

The serum SFA and MUFA was increased significantly (p < 0.001) in hepatitis B patients compared with normal controls and PUFA (n-3 and n-6) contents were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in hepatitis B patients in comparison to controls both total and free form (Figs. 2 and 3).

The serum FFA profile of hepatitis B patient’s, showed significantly elevated (p < 0.05) level of palmitic and stearic acid. The arachidic, nervonic, linoleic acid, α-linolenic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic and docosapentaenoic acids were significantly lower (< 0.05) in HBV patients in comparison to controls (Table 5). The serum SFA and MUFA was increased significantly (p < 0.05) in hepatitis B patients compared with normal controls and PUFA (n – 3 and n – 6) contents were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in hepatitis B patients in comparison to controls (Table 4).

Enzyme activities

Activities of elongase and desaturase enzymes by the FA composition with a range of serum lipids in hepatitis B patients and controls were calculated (Table 6). The elongase, Δ 5 desaturase, and Δ 6 desaturase activities were found lower whereas Δ 9 desaturase activity was found higher in hepatitis B patients in comparison to controls.

Fatty acids association with hepatitis B virus

Odds ratios were calculated (Table 7) for both hepatitis B patients and controls by quartile of serum fatty acids. Present study found an increased risk of HBV progression associated positively with increasing levels of myristic, palmitic, stearic, arachidic, palmitoleic, oleic and docosenoic acids. The significant association between serum FA’s and HBV was found when we compared the odds ratio for the highest quartile with the lowest one. For myristic acid odd ratio was found significant as 4.7 (95% CI: 0.2, 212.2; p value = < 0.01), for palmitic acid 3.2 (95% CI: 0.1, 121.0; p value = < 0.01). On the contrary PUFA was inversely associated with HBV progression; odds ratio for the highest quartile with the lowest one was calculated as linoleic acid 0.1 (95% CI: 0.003, 2.4; p value = < 0.01),α-linolenic acid 0.2 (95% CI: 0.01, 5.1; p value = 0.03), eicosatrienoic acid 0.2 (95% CI: 0.01, 4.8; p value = 0.02), arachidonic acid 0.8 (95% CI: 0.01, 42.6; p value = < 0.01), eicosapentaenoic acid 0.3 (95% CI: 0.01, 6.3; p value = 0.003) and docosapentaenoic acid odds ratio was 1.2 (95% CI: 0.2, 8.4; p value = 0.05).

Difference biomarkers

The Fig. 4 shows the plot of difference in the average fatty acids concentrations, which exhibited significant changes between hepatitis B cirrhosis with hepatitis B patients. The hepatitis B cirrhosis patient’s data was used from our previous paper [14]. The increase in nervonic, α-linolenic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acids were observed as potential differentiating biomarkers in hepatitis B in comparison of hepatitis B cirrhosis patients.

Discussion

HBV cells interact with cholesterol molecules for involving and spreading of infection in the target cells, although binding to the cell surface remains unaffected, which suggested that cholesterol within the viral envelope is required for later step in viral fusion [15]. The lipids have been considered to play an important role in the host immune response mechanism to infections [16]. Lipoproteins can bind a variety of viruses and reduces their toxic effects [17]. The binding of apolipoprotein H (apo H) to the HBsAg with subsequent lowering of the plasma apolipoprotein. The prolonged surge in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and interferon-alpha (IFN-α) has been linked with dyslipidemia in studies following the chronic state of the HBV-infection. Thus, interaction of HBsAg with apo H and lipidemic effect of cytokines could have contributed to the observed distortions in the various lipid indices of the hepatitis B infected population [18].

Decreased levels of total cholesterol and HDL-C in patients with asymptomatic chronic HBV infection may reduce their antiviral response. In patients with chronic hepatitis B, a high viral load is usually associated with active disease and histological progression in the long run [19]. The detailed mechanism responsible for the HDL-C reducing effect of chronic HBV infection remains to be clear. An enzyme involved in the biotransformation of HDL-C, Lecithin-Cholesterol Acyl Transferase (LCAT), was reported to reduce in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, probably with the reason of impaired hepatic synthesis [20]. This reduction may also decrease HDL-C and TC in the case of mild hepatic damage that is not reflected.

Chronic HBV infection was associated with the metabolic syndrome that possibly enhances the risk of fibrosis progression in liver cirrhosis and responsible for the development of HCC. If fibrosis continues unopposed, it would disrupt the normal architecture of the liver which alters the normal function of the organ, ultimately leading to pathophysiological damage of the liver [21]. In current study, the hepatitis B patients belongs to the early stage of fibrosis because cirrhosis represents the final stages of fibrosis. When liver function in cirrhotic liver proceeds into decompensated, it is no doubt that liver transplantation is the only effective way to save patients’ lives. The criteria of urgent liver transplantation depend upon the MELD score for non-cirrhotic patients with acute HBV flare up and liver failure. The MELD score was found 20 for hepatitis B patient showed 6.0% estimated mortality risk within 3 months. King College’s criteria was used for the evaluation of liver transplantation necessity, when the level of serum total bilirubin is 17.5 mg/dL, that indicates urgent liver transplantation upon MELD scores ≥35 at beginning and increased in the subsequent 1 to 2 weeks [22].

The percentile provides more information about the relationship of exposure to disease risk than the common method of grouping the data by specific percentiles, e.g. quartiles. It has been reported previously that the percentiles of triacylglycerol, serum fatty acids phospholipid and cholesterol ester provides population-based reference ranges against which the fatty acid status/lipid profile of individuals or groups can be compared. In addition, these reference ranges can be useful to researchers and epidemiologists [23].

It’s been identified in the current study, that the FA metabolic features are associated with HBV infection. The palmitic acid in hepatitis B patients is found significantly elevated and reduced stearic acid which may be due to impaired FA molecular structure elongation. This theory was explained by Moon et al., (2001) [24] after experimental studies on rodents, it is estimated that 90% of the endogenously synthesized stearate occurs through the elongation of palmitate in the endoplasmic reticulum and not through cytosolic fatty acids. The data presented suggest that long chain fatty acyl elongase is a member of the elusive elongation system present in the endoplasmic reticulum of mammals that is likely responsible for elongation of palmitic acid to stearic acid in vivo.

The low level of stearic acid while an increase in oleic acid and higher oleic to stearic acid ratios in hepatitis B patients has shown decreased levels of downstream metabolites arachidic acids; similar results are also reported in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis due to decreased activity of elongase and increased activity of Δ 9 desaturase [25].

The fatty acyl elongases (ELOVL; elongation of very long chain fatty acids) catalyze elongation process of FA. These enzymes are playing an important role in the initial step (condensation of FA) in elongation pathway. The seven family members of fatty acyl elongase (ELOVL1 to ELOVL7) have been identified in humans and mice with the characteristic of specific FA substrate. The ELOVL1, ELOVL3, ELOVL6, and ELOVL7 use SFA and MUFA as substrates, whereas ELOVL2, ELOVL4, and ELOVL5 prefer PUFA as substrates [26]. The elongase enzyme activity was found lower in hepatitis B patients in comparison to controls. The Elovl-6 enzyme elongates saturated FA palmitic to stearic acid [27]. The reduced level of stearic acid indicates the lower activity of the Elovl-6 enzyme. The decreased levels of PUFA in hepatitis patients in comparison to controls, which specifies the reduced activities of ELOVL2, ELOVL4 and ELOVL5 enzymes. The lower level of nervonic acid in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients in comparison of hepatitis B patients indicate the ELOVL1 lower activity in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients, because ELOVL1 production of lignoceric acid and nervonic acid acyl-CoAs is essential for the synthesis of C24 sphingolipids [28]. The nervonic acid is an essential molecule for the growth and maintenance of the brain and peripheral nervous tissue enriched in sphingomyelin, as sphingomyelin is a key constituent of myelin, it is abundant in the white matter of the brain [29].

FA of the n-6 series and n-3 series are essential for mammals. FA in the omega-6 family, linoleic (n-6) and arachidonic (n-6), and those in the omega-3 family, α-linolenic (n-3) must be supplied in human diets. The synthesis pathways of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids compete for the ∆5 and ∆6 desaturases though both enzymes preferentially catalyze the reactions of the n-3 pathway. The α-linolenic can be converted to eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid in the mammalian liver by a series of desaturation and elongation reactions and the ∆ 5-desaturation of arachidonic acid generates eicosapentaenoic acid (n-3) [30, 31]. The fatty acid desaturase 1 (FADS1) is also termed as ∆5 desaturase and fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) named as ∆ 6 desaturase, these enzymes catalyzed desaturation of PUFA in the liver, signifying as key enzymes for biosynthesis of long chain PUFA [32]. The reduced level of PUFA (n-3, n-6), is possibly due to lower activities of ∆ 5 desaturase and ∆ 6 desaturase enzymes and higher activity of ∆ 9 desaturase in hepatitis B patients that enumerate impair activity of FADS1 and FADS2.

The nervonic, α-linolenic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acids were higher in hepatitis B patients observed as potential differentiating biomarkers in comparison of hepatitis B cirrhosis patients. The lower level of α-linolenic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients indicate ∆5 and ∆6 desaturases was lower in hepatitis B cirrhosis in comparison of hepatitis patients. Arachidonic acid enhances the release of glutamate neurotransmitter, inhibits neurotransmitter uptake, stimulates stress hormone secretion, and enhances synaptic transmission. In the immune system, arachidonic acid can trigger an inflammatory response and increase oxidants in the brain and eicosapentaenoic acid can protect neurons from inflammation and oxidants [33].

The PUFA levels are reduced in hepatitis B patients includes linoleic, α- linolenic, eicosatrienoic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic acids furthermore responsible for the decrease in the total PUFA contents and PUFA to SFA ratio in HBV patients. The similar results were reported in alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients, as low levels of PUFA was found which in turn due to changes of Δ-5, Δ-6 and Δ-9 desaturase activity, which may lead to an increased degradation of PUFA due to lipid peroxidation [34].

In the hepatitis B patients, serum docosapentaenoic acid was elevated with downstream metabolite docosahexaenoic acid. The decline in docosahexaenoic acid is potentially important because docosahexaenoic acid is formed in peroxisomes from docosapentaenoic acid. The increase in docosapentaenoic acid along with declines in docosahexaenoic acid proposes the impaired peroxisomal PUFA metabolism [35]. These results provide motivation to forthcoming studies for the role of peroxisomal dysfunction in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B patients.

The palmitic and stearic acid in free form is significantly higher in hepatitis B patients. The FFA contain lipotoxic properties reported in the literature [36]. The saturated FFA’s, palmitic acid and stearic acid are more cytotoxic than monounsaturated FFAs. The foundation of reactive oxygen species through another lipid metabolic pathways, such as modulation of death receptor expression, ceramide synthesis and direct activation of cellular proapoptotic machinery are putative mechanisms by which lipoapoptosis is thought to occur [37], which promote the hepatic lipotoxicity in hepatitis B patients.

The eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid is reduced in hepatitis B patients. The FA’s immunomodulating activities are also reported in the literature [38]. The n-3 fatty acids contained the most effective immunomodulatory activities; eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid are highly biological active than α-linolenic acid [39]. The impaired immunity and deficiency of immunomodulating nutrients reactivity may be linked with hepatitis B antigen. It is possible that management of n-3 fatty acid decrease infection frequency and increases recovery of liver function in Hepatitis B patients suffering from hepatitis B infection.

Host immune factors play essential roles in the outcome of HBV infection. Thus, ineffective immune response against HBV may result in persistent virus replications and liver necro-inflammations. Cytokine balance was shown to be an important immune characteristic in the development and progression of hepatitis B, as well as in an effective antiviral immunity. The cytokines are the primary causes of inflammation and mediates liver injury after HBV infection, the roles of various cytokines [including T helper type 1 cells (Th1), Th2, Th17, regulatory T cells (Treg)-related cytokines] in different phases of HBV infection and cytokine-related mechanisms for impaired viral control and liver damage during HBV infection. Th17 cells are a newly identified subset of T helper cells and are closely related to the progression of HBV disease. Research interest in these cells has indicated that patients with chronic HBV infection were found to have significantly elevated Th17 cell frequency and Th17-secreted cytokines, including interleukin IL-17A, IL-21, and IL-22, and it was proposed that these pro-inflammatory effectors may perform a vital function in pathogenesis of prolonged hepatitis B infection [40].

The present study supports an inverse association of PUFA with HBV progression. The lipids emulsion has the capability to transform the immune mechanism. The n-3fatty acids are known for their capability to modify leukocyte activity, amend lipid-mediator generation and to modulate cytokine release. The declining of infectious phase was reported after the initiation of n-3 FA’s a by enteral nutrition to hepatic trauma patients [41]. It is also suggested by the current study that use of n-3 and n-6 FA’s significantly decreases the rate and complications of disease when meaningfully added in the diet of hepatitis B patients.

Conclusion

Hypolipidemia is observed in hepatitis B patients due to impaired liver function. The increased level of SFA and decreased the level of PUFA were detected in hepatitis B patients due to altered activities of enzyme elongase, ∆5, ∆6 and ∆9-desaturase with impaired PUFA metabolism and non-enzymatic oxidation.

Limitations of the study

In present study numbers of samples are not large enough, though ideally larger group of subjects are required to delineate the role of lipid synthesis across the HBV spectrum.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- D5D:

-

∆5-desaturase

- D6D:

-

∆6-desaturase

- D9D:

-

∆9-desaturase

- FA:

-

Fatty acids

- FADS:

-

Fatty acid desaturase

- FAS:

-

Fatty-acid synthase

- FID:

-

Flame ionization detector

- GC:

-

Gas chromatography

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- PUFA:

-

Poly unsaturated fatty acid

- SCD:

-

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acid

- TAG:

-

Triacylglycerol

- VLDL-C:

-

very low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

References

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ (Updated July 2017).

Noorali S, Hakim ST, McLean D, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus genotype D in females in Karachi, Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2(5):373–8.

Ress C, Kaser S. Mechanisms of intrahepatic triglyceride accumulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jan 28;22(4):1664.

Miyoshi H, Moriya K, Tsutsumi T, Shinzawa S, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Fujinaga H, Goto K, Todoroki T, Suzuki T, Miyamura T. Pathogenesis of lipid metabolism disorder in hepatitis C: polyunsaturated fatty acids counteract lipid alterations induced by the core protein. J Hepatol. 2011;54(3):432–8.

Kwarteng JK, Owusu L, Afihene M, et al. Lowered serum triglyceride levels among chronic hepatitis B-infected patients in Ghana. J Sci Technol. 2012;32(3):1–10.

Kwarteng JK, Owusu L, Afihene M, Mica E, Opare-Sem O, Arthur FK. Lowered serum triglyceride levels among chronic hepatitis B-infected patients in Ghana. J Sci Technol (Ghana) 2012;32(3):1–0.

Serviddio G, Bellanti F, Villani R, Tamborra R, Zerbinati C, Blonda M, Ciacciarelli M, Poli G, Vendemiale G, Iuliano L. Effects of dietary fatty acids and cholesterol excess on liver injury: a lipidomic approach. Redox Biol. 2016;9:296–305.

Conlon BA, Beasley JM, Aebersold K, et al. Nutritional management of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Nutrients. 2013;5(10):4093–114.

Unger RH. The physiology of cellular liporegulation. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003 Mar;65(1):333–47.

Carpentier YA, Portois L, Sener A. Correlation between liver and plasma fatty acid profile of phospholipids and triglycerides in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22(2):255–62.

Arain SQ, Talpur FN, Channa NA. Clinical evaluation and serum lipid profile between individuals with acute hepatitis C. IJBRR. 2015;6:37–45.

Gray RG, Kousta E, McCarthy MI, Godsland IF, Venkatesan S, Anyaoku V, Johnston DG. Ethnic variation in the activity of lipid desaturases and their relationships with cardiovascular risk factors in control women and an at-risk group with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12(1):25.

Jiang M, Liu F, Xiong WJ, Zhong L, Chen XM. Comparison of four models for end-stage liver disease in evaluating the prognosis of cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2008 Nov 14;14(42):6546.

Arain SQ, Talpur FN, Channa NA, Ali MS, Afridi HI. Serum lipid profile as a marker of liver impairment in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):51.

Bremer CM, Bung C, Kott N, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection is dependent on cholesterol in the viral envelope. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11(2):249–60.

Field CJ, Johnson IR, Nutrients SPD. Their role in host resistance to infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(1):16–32.

Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Lipids: a key player in the battle between the host and microorganisms. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(12):2487–9.

Agbecha A, Usoro CA, Etukudo MH. Serum lipids in chronic viral hepatitis B patients in Makurdi, Nigeria. CHRISMED J Health Res. 2017;4(2):81.

Niederau C. Chronic hepatitis B in 2014: great therapeutic progress, large diagnostic deficit. WJG. 2014;20(33):11595–617.

Wong T, Lee SS, Hepatitis C. A review for primary care physicians. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):649–59.

Wang CC, Tseng TC, Kao JH. Hepatitis B virus infection and metabolic syndrome: fact or fiction? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(1):14–20.

Lee WC, Lee CS, Wang YC, Cheng CH, Wu TH, Lee CF, Soong RS, Chang ML, Wu TJ, Chou HS, Chan KM. Validation of the model for end-stage liver disease score criteria in urgent liver transplantation for acute flare up of hepatitis B. Medicine. 2016;95(22)

Bradbury KE, Skeaff CM, Crowe FL, Green TJ, Hodson L. Serum fatty acid reference ranges: percentiles from a New Zealand national nutrition survey. Nutrients. 2011 Jan 20;3(1):152–63.

Moon YA, Shah NA, Mohapatra S, et al. Identification of a mammalian long chain fatty acyl elongase regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):45358–66.

Puri P, Wiest MM, Cheung O, et al. The plasma lipidomic signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol. 2009;50(6):1827–38.

Xue X, Feng CY, Hixson SM, Johnstone K, Anderson DM, Parrish CC, Rise ML. Characterization of the fatty acyl elongase (elovl) gene family, and hepatic elovl and delta-6 fatty acyl desaturase transcript expression and fatty acid responses to diets containing camelina oil in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Comp Biochem Physiol B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;175:9–22.

Wang Y, Torres-Gonzalez M, Tripathy S, Botolin D, Christian B, Jump DB. Elevated hepatic fatty acid elongase-5 activity affects multiple pathways controlling hepatic lipid and carbohydrate composition. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(7):1538–52.

Sassa T, Kihara A. Metabolism of very long-chain fatty acids: genes and pathophysiology. Biomol Ther. 2014;22(2):83.

Kageyama Y, Kasahara T, Nakamura T, Hattori K, Deguchi Y, Tani M, Kuroda K, Yoshida S, Goto YI, Inoue K, Kato T. Plasma nervonic acid is a potential biomarker for major depressive disorder: a pilot study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx089.

White HM, Richert BT, Latour MA. Impacts of nutrition and environmental stressors on lipid metabolism. InLipid metabolism. InTech. 2013;211–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/51204.

Kaur N, Chugh V, Gupta AK. Essential fatty acids as functional components of foods-a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2014 Oct 1;51(10):2289–303.

Araya J, Rodrigo R, Pettinelli P, Araya AV, Poniachik J, Videla LA. Decreased liver fatty acid Δ-6 and Δ-5 desaturase activity in obese patients. Obesity. 2010 Jul 1;18(7):1460–3.

Song C, Leonard BE. Depression and stress. Role of n-3 and n-6 Fatty Acids. 2007:754–60.

Ristic-Medic D, Takic M, Vucic V, et al. Abnormalities in the serum phospholipids fatty acid profile in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis - a pilot study. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2013;53(1):49–54.

Ferdinandusse S, Denis S, Mooijer PA, et al. Identification of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of docosahexaenoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(12):1987–95.

Arain SQ, Talpur FN, Channa NA. A comparative study of serum lipid contents in pre and post IFN-alpha treated acute hepatitis C. BMC Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14(117):1–9.

Malhi H, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, et al. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(17):12093–101.

Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, et al. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatol. 2004;40(1):185–94.

Li Z, Berk M, McIntyre TM, et al. The lysosomal mitochondrial axis in free fatty acid-induced hepatic lipotoxicity. Hepatol. 2008;47:1495–503.

Wu W, Li J, Chen F, Zhu H, Peng G, Chen Z. Circulating Th17 cells frequency is associated with the disease progression in HBV infected patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:750–7.

Wu Z, Qin J, Pu L. omega-3 fatty acid improves the clinical outcome of hepatectomized patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biomed Res 2012; 26(6):395–399.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to the doctors and staff of Taluka hospital TandoAdam, Sindh, Pakistan for their cooperation in samples collection taking consent from patients and fill the questioner voluntary.

Funding

The study work was completed with the support of departmental facilities at National Centre of Excellence in Analytical Chemistry and Institute of the Biochemistry University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. Moreover the staff of Taluka hospital TandoAdam, Sindh, Pakistan helped in collecting samples and taking consent from patients voluntary.

Availability of data and materials

SQA and FNT are responsible for raw fatty acid data, whereas, SQA and NAC are responsible for the raw lipid profile data sharing and publication and is available in the Additional files 1 and 2. All authors are supporters of data sharing and release from all types of research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NAC acquired the permission from Ethical Committee. Sampling was done by SQA with the help of the staff at Taluka hospital TandoAdam district Sanghar. SQA and FNT carried out the serum lipid analysis by Gas chromatography and compiled the results. While NAC helped in Microlab analysis. MSA and HIA helped in statistical analysis. The manuscript was drafted by SQA and FNT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients were well informed in their local languages and with their full knowledge and understanding a written consent were signed in their familiar languages, in case of illiterate patients verbal information provided to the patient and consent was taken with thumb impressions in the presence of their trustworthy witnesses and enrolled in the study. The direct benefits receive as participants were free analysis of lipid profile and fatty acid composition, counted as social service in public benefit.

Consent for publication

Participants were informed for data sharing while their name and identity will be hidden as per consent.

Competing interest

Sadia Qamar Arain, Farah Naz Talpur, Naseem Aslam Channa, Muhammad Shahbaz Ali, and Hassan Imran Afridi declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Chromatogram of fatty acids standards. Figure S2 (a). Chromatogram of serum total fatty acids of hepatitis B patients. (b). Chromatogram of serum total fatty acids of control subject. Figure S3 (a). Chromatogram of serum free fatty acids of hepatitis B patient. (b). Chromatogram of serum free fatty acids of control subject. (DOCX 1378 kb)

Additional file 2:

Lipid profile and serum fatty acid composition data of hepatitis B patients and controls. (XLSX 57 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Arain, S.Q., Talpur, F.N., Channa, N.A. et al. Serum lipids as an indicator for the alteration of liver function in patients with hepatitis B. Lipids Health Dis 17, 36 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0683-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0683-y