Abstract

Across a broad range of human cancers, gain-of-function mutations in RAS genes (HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS) lead to constitutive activity of oncoproteins responsible for tumorigenesis and cancer progression. The targeting of RAS with drugs is challenging because RAS lacks classic and tractable drug binding sites. Over the past 30 years, this perception has led to the pursuit of indirect routes for targeting RAS expression, processing, upstream regulators, or downstream effectors. After the discovery that the KRAS-G12C variant contains a druggable pocket below the switch-II loop region, it has become possible to design irreversible covalent inhibitors for the variant with improved potency, selectivity and bioavailability. Two such inhibitors, sotorasib (AMG 510) and adagrasib (MRTX849), were recently evaluated in phase I-III trials for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with KRAS-G12C mutations, heralding a new era of precision oncology. In this review, we outline the mutations and functions of KRAS in human tumors and then analyze indirect and direct approaches to shut down the oncogenic KRAS network. Specifically, we discuss the mechanistic principles, clinical features, and strategies for overcoming primary or secondary resistance to KRAS-G12C blockade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

KRAS is the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancer and has challenged the development of clinical anticancer therapeutics in the last 30 years.

-

Mutated KRAS oncoprotein disrupts GAP-mediated GTP hydrolysis and thus remains in a continuous GTP binding activation state.

-

Small-molecule inhibitors that directly target KRAS-G12C mutants provide new tools for precision oncology.

-

Clinical trials involving covalent KRAS-G12C inhibitors (adagrasib and sotorasib) have shown promising activity against lung cancers harboring KRAS-G12C mutations.

-

Secondary KRAS mutations, gain-of-function mutations of the MAPK pathway, loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes, and other gene alterations are conducive to acquired resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors.

-

The design and implementation of strategies to minimize or overcome drug resistance is an important goal for the further development of KRAS inhibitors.

Introduction

The RAS gene was initially identified as a virus-encoded gene in 1964 [1], and later was found to be a genome-encoded oncogene that is frequently mutated in human cancers [2]. Thus, activating mutations of RAS are found in 19% of neoplasias, corresponding to approximately 3.4 million new diagnoses of malignant disease worldwide each year [2]. The RAS gene family includes HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS, which are encoding proteins that play partially overlapping but specific roles in signaling transduction [3]. For example, the knockout of Kras is embryonically lethal in mice, while the depletion of Nras or Hras does not affect development [4]. The mutation of human KRAS was first detected in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [5,6,7]. The earliest evidence that RAS is an oncogene was based on the fact that transfecting mouse Kras causes morphological transformation of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts [8]. Subsequent studies involving transgenic mice confirmed that the mutation of Hras, Nras, or Kras mimicked human oncogenesis by triggering the stochastic transformation of cells [9,10,11,12]. Clinical studies revealed the prognostic impact of RAS mutations in certain cancers [2]. However, in spite of decades-long efforts of academia and industry to target RAS protein for cancer therapy [13], the design of direct RAS pharmacological inhibitors has only achieved a major breakthrough during recent years [14]. In 2021, two covalent inhibitors of KRAS-G12C protein (hereafter referred to as G12Ci), sotorasib (AMG 510) [15] and adagrasib (MRTX849) [16], were clinically approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to treat patients with advanced NSCLC carrying the KRAS-G12C mutation. Monotherapies or combination therapies using G12Ci are being evaluated in clinical trials for advanced or metastatic solid cancer, including NSCLC, colorectal cancer (CRC), and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [17]. This progress is inspiring scientists to continue to design drugs targeting key oncogenic drivers, even those that previously were considered to be “undruggable” like KRAS [18].

Here, we summarize recent therapeutic advances in mutant KRAS blockade that have led to clinical approval or are currently being evaluated in trials (Table 1), while discussing attempts to target upstream regulators, downstream effectors, and mutant KRAS protein itself. We also discuss the challenges associated with G12Ci-based treatments and the future prospects of this evolving topic.

Type and frequency of KRAS mutation

RAS genes are mutated at different prevalence rates in human cancers (Fig. 1a) [19]. Elucidating similarities and differences among these RAS mutations from a developmental or evolutionary perspective remains a challenge [20, 21]. Some RAS gene mutations are innocuous, but others cause cancer by producing oncoproteins. For example, three amino acid residues (G12, G13, and Q61) in HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS are mutational hot spots, though with distinct frequencies in different human tumor types (Fig. 1b) [14]. A KRAS-G12 mutation is a common event in pancreatic (91%), colorectal (68%), and lung adenocarcinoma (85%; a subtype of NSCLC) [14]. Among these, KRAS-G12D is the leading mutation in pancreatic (45%) and colorectal adenocarcinoma (45%), while KRAS-G12C mainly occurs in lung adenocarcinoma (46%) (Fig. 1c) [14]. In contrast, 85% of human melanomas have KRAS-Q61 mutations, especially Q61R (46%) [14]. Whole-exome sequencing of human PDAC or NSCLC tumors shows that, despite the genetic heterogeneity within the tumor, KRAS is mutated in different regions [22, 23]. Consistent with this, the co-mutational interactions between each KRAS allele and other unrelated genes are highly tissue-specific, emphasizing the complexity of cell type-specific oncogenesis [24]. KRAS mutations usually co-occur with mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) in PDAC, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) and/or serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11) in NSCLC, or APC regulator of WNT signaling pathway (APC) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) in CRC. While mutations in exon 2 of KRAS are the most common, it is important to note that they affect the differential use of exon 4, giving rise to two splice variants, KRAS4A and KRAS4B (Fig. 1b) [25]. These KRAS variants differ in their C-terminal membrane targeting region, posttranslational modifications, and interactomes, thus exhibiting different signal behaviors in development, metabolism, and proliferation [26,27,28]. Therefore, to target KRAS, investigators must consider changes in the protein structure caused by point mutations, but also isoform-specific properties [29].

Type and frequency of RAS mutations in human cancers. a. Somatic mutations of RAS oncogene in the top 10 human cancers. b. The frequency and location of G12, G13, and Q61 mutations in the exons of RAS oncogenes. c. The frequency and type of KRAS mutations in codon 12 in pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma. The data were derived from recent studies using the COSMIC or cBioPortal database [2, 14, 19]

Prognostic and predictive value of KRAS mutations

Depending on the clinical settings, the prognostic and predictive values of KRAS mutations are variable and even conflicting. For example, an early study of lung adenocarcinoma patients showed that the KRAS mutation in code 12 is an unfavorable prognostic factor [30]. Similarly, a meta-analysis found that KRAS mutations are associated with poor survival in patients with early resectable NSCLC [31]. In contrast, a pooled analysis of NSCLC patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy revealed that a KRAS mutation was not a prognostic factor [32]. Of note, a KRAS mutation is a negative predictor of response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; e.g., cetuximab, gefitinib, or erlotinib) (Table 2) [33,34,35,36], but a positive predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs; including anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1) (Table 3) [37,38,39]. However, response rates are variable and dissenting reports suggest that KRAS mutations cannot guide the therapeutic choice between TKIs and ICIs in NSCLC patients [40, 41].

In PDAC, patients with KRAS-G12D mutations (but not total KRAS mutations) have a worse prognosis than patients with wild-type KRAS [42,43,44]. Other studies suggest that the prognosis of KRAS-G12V is poorer than that for other mutations [45, 46], commensurate to a KRAS-G12V–associated increase in circulating regulatory T cells that most likely limits antitumor immunity [47]. In advanced PDAC, KRAS mutation status is predictive for the efficacy of erlotinib rather than prognostic [48]. This contradicts other studies reporting that KRAS wild-type patients with PDAC have a significant advantage after treatment with gemcitabine/nimotuzumab [49] or gemcitabine/erlotinib [50] with respect to overall survival. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has recently become a minimally invasive tool used in precision oncology to evaluate genetic alterations. Mutant KRAS in ctDNA might be a more sensitive predictor of survival than the ELISA-based detection of cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) [51, 52]. Before a clear conclusion can be drawn regarding the impact of KRAS mutations on overall survival in PDAC [53, 54], additional data from analyses of other genetic alterations are needed.

In localized CRC, KRAS mutations usually suggest a poor prognosis [55,56,57]. Some KRAS mutations, including KRAS-G12V, are more aggressive than others [58]. In contrast to BRAF mutations, KRAS mutations have no major prognostic value in advanced CRC patients [59]. The association between KRAS mutations and poor clinical outcomes from TKI treatment has been confirmed in several independent studies [60,61,62,63]. Compared with KRAS-G12V mutations or wild-type tumor groups, CRC patients with KRAS-G13D mutations are insensitive to cetuximab therapy [64, 65]. Nevertheless, the impact of KRAS mutations on cetuximab treatment needs to be further evaluated in prospective randomized trials. Reportedly, KRAS-G12D–mediated inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 2 (IRF2) drives CRC resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in preclinical models [66]. However, the clinical implications of these findings remain elusive.

In conclusion, the prognostic and predictive values of KRAS mutations are affected by many factors, such as tumor type, stage, patient age, sex, the coexistence of mutations affecting other oncogenes or tumor suppressors, and treatment regimens. For this reason, the clinical utility of detecting KRAS mutations may be over- or underestimated. Careful meta-analyses that avoid nonrandom systematic errors due to variations between trials [67] are needed to clarify this issue.

Activation and modulation of KRAS mutations

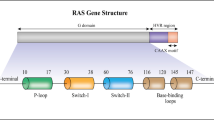

Wild-type KRAS protein mostly resides on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane, as well as at membranes of intracellular organelles, and is guided by protein localization signals (such as lipid moieties added to the carboxyl terminus) [68]. The RAS family of proteins belongs to a class of enzymes called small GTPases, which play a central role in cell signal transduction [69]. The functions and activities of RAS protein depend on the transition from an inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound state to an active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound state (Fig. 2a) [69]. Normally, this conversion process of RAS status is reversible and is maintained in a balanced manner by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). GAPs, such as neurofibromin 1 (NF1), accelerate the GTP hydrolysis of RAS, leading RAS to an inactive state [70, 71]. GEFs, including the most universally expressed SOS Ras/Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1 (SOS1), are responsible for producing active GTP-bound RAS [72,73,74]. The balance between hydrolysis and exchange determines the level of activated KRAS in the cell [75]. Oncogenic mutations of RAS disrupt GAP-mediated GTP hydrolysis, allowing these oncoproteins to accumulate in a continuous GTP-binding active state (Fig. 2b) [13]. Among distinct KRAS mutants, the KRAS-G12C protein exhibits the highest intrinsic GTP hydrolysis rate [76].

Principle of inhibiting oncogenic KRAS activation. a. The wild-type (WT) KRAS protein maintains a balance between the inactive state of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) binding and the active state of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) binding. This process is mediated by GTPase activating protein (GAP) and guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). b. The KRAS oncoprotein (e.g., KRAS-G12C) disrupts GAP-mediated GTP hydrolysis, allowing these mutants to accumulate in a continuous GTP-binding active state, which is responsible for oncogenic activity. c. The covalent inhibitor of KRAS-G12C protein (G12Ci) achieves allosteric inhibition of mutant cysteine 12 (12C) to prevent GEF-catalyzed nucleotide exchange and block subsequent effector pathways

The upstream regulators of the RAS pathway involve receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which are cell surface receptors for many growth factors, cytokines, and hormones (Fig. 3). One particular RTK subclass, the EGFR family, is composed of four closely related members, EGFR (also known as ERBB1 or HER1), ERBB2/HER2, ERBB3/HER3, and ERBB4/HER4. EGFR/ERBB1, the best characterized activator of RAS signaling, acts through binding to an adaptor protein, namely growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (GRB2) [77, 78]. GRB2 further mediates the recruitment and activation of SOS1- and SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2) to activate GTP-bound RAS [79,80,81,82,83,84]. Activated EGFR mutations are often found in human cancers, especially NSCLC, and lead to the constitutive activation of downstream signals, including RAS [85]. G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), the largest group of membrane receptors, also participate in RAS activation [86, 87]. Thus, the interplay between RTKs and GPCRs may increase the plasticity of RAS activation.

Indirect KRAS suppression strategy. The activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, such as members of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family, activate KRAS through the growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2)-SH2–containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2)-SOS Ras/Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1 (SOS1) pathway. The mutant KRAS protein accumulates in the guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound state, leading to the activation of downstream effector pathways, especially the RAF-MEK-extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT-mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. The localization of KRAS on the cell membrane is the first step in subsequent KRAS activation, which is mediated by enzymes, including but not limited to farnesyltransferase (FT), geranylgeranyltransferase 1 (GGT1), and isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (ICMT). In addition to directly inhibiting KRAS (exemplified by covalent allele-specific inhibitors that bind to KRAS-G12C), multiple approaches can indirectly inhibit the oncogenic pathway of KRAS by targeting upstream regulators, downstream effectors, and KRAS expression and processing. The main drugs or reagents used for indirect KRAS inhibition are shown in red (for clinical trials or approved for use in patients) or green (for preclinical research)

The downstream effectors of the RAS pathway are mainly involved in the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways, which favor anabolic processes including cell growth, protein translation, and proliferation (Fig. 3) [88, 89]. Thus, the constitutive activation of membrane RAS-dependent signal pathways favors oncogenesis [90]. The aggregation of mitochondrial KRAS-G12V protein also favors tumor cell growth through metabolic effects [91]. Another distinctive feature of KRAS-G12D protein is that it can be released by PDAC cells into the tumor microenvironment and then mediates the polarization of pro-tumor macrophages (Fig. 4) [92]. Indeed, PDAC patients with KRAS-G12D–positive macrophages exhibit low survival rates [92]. There is also strong preclinical evidence that mutated KRAS requires additional factor (such as chronic inflammation or a high-fat or high-iron diet) to deploy its full carcinogenic activity [93,94,95]. Further work is needed to elucidate the likely complex cell-autonomous and non-autonomous effects of mutated and unmutated KRAS protein on the tumor microenvironment [21].

The immunosuppressive function of extracellular KRAS-G12D protein in the tumor microenvironment. KRAS-G12D protein can be released during ferroptosis, which is a regulated cell death caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent lipid peroxidation. The release of KRAS-G12D protein is mediated by exosomes, which are cargo extracellular vesicles produced by multivesicular bodies derived from endosomes. The small GTPase RAB27A regulates exocytosis of multivesicular endosomes, which leads to exosome secretion. This process is further enhanced by autophagy-related 5 (ATG5)-dependent autophagosome formation and autophagy-meditated secretion. Once released, the extracellular KRAS-G12D protein from exosomes is taken up by advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor (AGER) on macrophages, leading to phosphorylation and activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Nuclear STAT3 acts as a transcription factor to produce cytokines, such as transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1), interleukin 10 (IL10), and arginase 1 (ARG1), for polarization of M2 macrophages, which limits antitumor immunity

Indirect KRAS suppression strategies

The most successful way to inhibit oncogenic kinases is to develop inhibitors that compete with ATP to bind to the kinase domain. However, KRAS uses GTP instead of ATP as a phosphate donor for signal transmission. Attempts to directly enzymatically inhibit KRAS function have been largely frustrated, leading to the development of indirect methods for KRAS inhibition. Below, we highlight some representative drugs that exemplify the main strategies for indirectly targeting mutant KRAS (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Inhibition of KRAS expression

AZD4785 is a constrained ethyl-containing antisense oligonucleotide that is complementary to the sequence of the 3'UTR of KRAS mRNA, leading to the downregulation of wild-type and mutant KRAS protein [96]. AZD4785 selectively inhibits the proliferation of mutant KRAS-driven tumor cells in vitro or in xenograft models [96, 97]. However, intravenously infused AZD4785 failed to completely reduce KRAS mRNA in patients with NSCLC (NCT03101839) [14], calling for adjustments of the dose and method of administration. Another approach for transcriptionally inhibiting KRAS expression involves the use of a specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) named siG12D-LODER that specifically targets G12D but not wild-type KRAS. This agent showed promise in a phase I study (NCT01188785) in combination with chemotherapy (gemcitabine or FOLFIRINOX, i.e., a combination of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) in 12 patients with advanced PDAC [98]. A phase II study (NCT01676259) evaluating this therapeutic strategy is now underway.

Inhibition of KRAS processing

The location of RAS on the cell membrane is the initial step of RAS activation and requires multiple posttranslational processing steps, especially lipid-related prenylation [99]. The two enzymes involved in KRAS prenylation are farnesyltransferase (FT) and geranylgeranyltransferase 1 (GGT1). Although preclinical studies suggest anticancer activity for FT inhibitors (for example, tipifarnib/R115777 and lonafarnib/SCH 66336) against RAS-mutant tumors, clinical studies have been disappointing [100,101,102,103]. One possible explanation for this failure is functional redundancy among FT and GGT1 [104]. A single molecule with dual inhibitory activity on FT and GGT1, such as FGTI-2734 [105], might have the potential to eliminate RAS-mutant tumors. Alternatively, targeting downstream RAS processing enzymes, such as isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (ICMT), may be attempted. Two ICMT inhibitors (cysmethynil and UCM-1336) impair the membrane localization of RAS (including that of KRAS) [106], but their application in vivo remains to be studied. Once RAS is effectively processed, membrane RAS protein undergoes activating self-association, and this process can be blocked by a synthetic binding protein called NS1 [107]. Since NS1 is an alien protein, its possible recognition by the immune system needs to be evaluated before it is introduced into clinical trials.

Inhibition of upstream signaling molecules

Gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib (pan-EGFR inhibitors), icotinib, and osimertinib are first-line EGFR TKIs for treating NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations [108]. Lapatinib is the first dual inhibitor of EGFR and ERBB2/HER2 for treating ERBB2-positive breast cancer, whereas brigatinib is a mixed inhibitor of ALK and EGFR used for the treatment of metastatic NSCLC. The clinical benefit of small-molecule EGFR inhibitors on KRAS-mutant cancers is context-dependent. For example, gefitinib alone is not effective against KRAS-mutant NSCLC [109], while the combination of erlotinib and gemcitabine provides transient benefit to patients with KRAS-mutant PDAC [110]. Another approach to inhibit EGFR activity consists of the use of monoclonal antibodies [108]. Cetuximab and panitumumab are approved for metastatic CRC, while necitumumab is used for the treatment of squamous NSCLC. However, some studies suggest that antibodies against EGFR have no effect on KRAS-mutant CRC [60, 62], while others report that CRC patients with KRAS-G13D are sensitive to cetuximab treatment [65]. Regardless, acquired KRAS mutations are a common mechanism of resistance to EGFR inhibitors [111]. Recently, rybrevant, a bispecific antibody against EGFR and MET receptors, has been approved for the treatment of NSCLC patients with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations. Other EGFR-specific monoclonal antibodies in clinical development are zalutumumab, nimotuzumab, and matuzumab. It will be important to understand how preexisting or acquired KRAS mutations will affect the clinical activity of such drugs.

The proteins SOS1 and SOS2 promote RAS activation by binding to GRB2. The SOS1 inhibitor BI-1701963 is used in combination with MEK inhibitors (trametinib and BI-3011441) or a topoisomerase I inhibitor (irinotecan) in clinical trials enrolling patients with advanced or metastatic solid cancer (Table 1). BI-1701963 has been designed to bind to the catalytic domain of SOS1 to prevent its interaction with KRAS-GDP [79]. SOS1 mutations lead to dysregulated enzymatic activities, which may cause drug resistance [112]. Because there is currently no SOS2-specific inhibitor, it is unclear whether targeting SOS2 would have the same effects as SOS1 inhibitors. It can be speculated that pan-SOS inhibitors might be particularly efficient in blocking the activation of RAS.

SHP2 not only mediates the RTK-stimulated activation of RAS [113] but also acts as a promoter of immune checkpoint pathways [114]. Certain SHP2 inhibitors are in early-phase clinical development for treating advanced or metastatic solid cancer (Table 1). TNO155 is an allosteric inhibitor that maintains SHP2 in a self-inhibited conformation [115]. Preclinical studies have shown promising anticancer activity from TNO155 combined with inhibitors of EGFR, MEK, ERK, CDK4/6, or KRAS-G12C and anti–PD-1 antibodies in xenograft models of NSCLC or CRC cells [116]. The efficacy and toxicity of combination regimens involving TNO155 together with TKIs or ICIs remain to be determined in clinical trials.

Inhibition of downstream signaling molecules

Oncogenic transformation mediated by RAS requires the downstream activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. In theory, inhibition of any of these effectors should block oncogenic KRAS signaling. In fact, these two pathways intersect with each other and even form a feedforward loop to activate KRAS as an upstream signal [14]. Nonetheless, the success of targeting KRAS-mutant tumors by inhibiting single downstream molecules has been limited [18]. Despite these results, certain MAPK and PI3K pathway inhibitors have been approved or are entering clinical trials for combination therapies (Table 1) [88, 89]. In this section, we highlight some of these drugs and their application for KRAS-mutant cancers.

RAF inhibitors

The RAF family consists of ARAF, BRAF, and CRAF, all sharing RAS as a common upstream activator. Belvarafenib (HM95573) is a pan-RAF dimerization inhibitor that demonstrates selective anticancer activity with either cobimetinib or cetuximab in preclinical models, as well as in cancer patients with RAS or RAF mutations, especially melanoma patients (Table 1). ARAF mutations are conducive to resistance to bevacafenib, indicating that the RAF subtype has a compensatory function, and a secondary mutation of a RAF member may reactivate the MAPK pathway to avoid cell death [117].

LXH-254, an ATP-competitive inhibitor of BRAF and CRAF [118], is used in multiple clinical trials for patients with NSCLC or melanoma (Table 1). The anticancer activity of LXH-254 is demonstrated in tumors carrying BRAF/RAS co-mutations, but it has moderate activity against cancers driven by KRAS mutants [119]. ARAF may also mediate LXH-254 resistance in RAS-mutant cancer cell lines [119], supporting the hypothesis that all RAF isoforms need to be suppressed at the same time in order to achieve tangible antineoplastic effects.

Lifirafenib (BGB-283), a dual inhibitor of RAF and EGFR, is being used in clinical studies enrolling patients with BRAF- or KRAS/NRAS-mutated solid tumors [120]. Preclinical study suggests that lifirafenib enhances the antitumor activity of MEK inhibitors (mirdametinib and selumetinib) in KRAS-mutant tumors [121]. A phase I study on the safety and pharmacokinetics of the combination with lifirfenib and mirdametinib in KRAS-mutant NSCLC is ongoing (NCT03905148).

Other RAF inhibitors, such as PLX8394 and TAK-580 (MLN2480), are being evaluated as single-agent therapeutics in patients with advanced unresectable solid tumors (NCT02428712) or low-grade glioma (NCT03429803), respectively. Vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib are RAF inhibitors approved for the treatment of tumors with BRAF-V600E/K, but not RAS, mutations. It appears that monotherapy with RAF inhibitors is not efficient against cancers with KRAS mutations, suggesting that combination with other MAPK pathway inhibitors should be attempted.

MEK inhibitors

Three MEK inhibitors, including trametinib (GSK1120212), cobimetinib (XL518), and binimetinib (MEK162), are approved in combination with BRAF inhibitors for the treatment of patients with advanced melanoma harboring BRAF mutations (V600E or V600K). Although the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244) is not efficient against melanoma, it has recently been approved for the treatment of neurofibromatosis type 1 in children. Compared with standard treatments, MEK inhibitors alone are not efficient against solid tumors driven by KRAS mutations [122,123,124,125]. However, the combination of a MEK inhibitor and RAF inhibitor has shown promising activity against KRAS-mutant (especially KRAS-G13D) cells in vitro [126]. These findings provide the rationale for ongoing clinical trials that combine RAF (belvarafenib or LXH-254) and MEK inhibitors (cobimetinib or trametinib) to treat solid cancer with KRAS mutations (Table 1).

Two MEK inhibitors, pimisertib (MSC1936369B) and mirdametinib (PD0325901), are being evaluated for clinical activity against KRAS-mutant solid cancers (Table 1). Pimasertib alone is better than dacarbazine for improving progression-free survival in patient with BRAF- and NRAS-mutant melanoma [127, 128]. A combination of pimasertib and the MDM2 (a repressor of tumor suppressor TP53) inhibitor SAR405838 has shown preliminary antitumor activity in the treatment of solid cancers with RAS or RAF mutations [129]. Thus, targeting MEK combined with pharmacological TP53 induction may constitute a strategy for combating KRAS-mutant cancers.

ERK inhibitors

Although ERK inhibition is an effective strategy to overcome resistance to upstream MEK or RAF inhibitors [130,131,132], the clinical development of ERK inhibitors has been retarded when compared to that of MEK and RAF inhibitors. In 2020, the FDA granted an expanded access program for the ERK inhibitor ulixertinib (BVD-523) for the treatment of cancer patients with abnormal MAPK pathways, including but not limited to those involving KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, BRAF, MEK, and ERK mutations [133]. Ulixertinib is currently being evaluated in combination with hydroxychloroquine (an autophagy inhibitor) or palbociclib (a CDK4/6 inhibitor) in patients with advanced pancreatic and other solid tumors (NCT041452973 and NCT03454035).

Certain ERK inhibitors, such as LY3214996, GDC-0994, and MK-8353, alone or in combination with other drugs, are in the early stages of clinical development. LY3214996 is being used with abemaciclib, hydroxychloroquine, or RMC-4630, in solid tumors, including KRAS-mutant cancers (Table 1). Despite strong preclinical data [134], patients with advanced solid tumors cannot tolerate combination therapy with GDC-0994 and cobimetinib [135]. However, GDC-0994 alone has acceptable side effects and showed anticancer activity in two patients with BRAF-mutant CRC [136]. The toxicity of GDC-0994 in combination with other MAPK inhibitors needs to be further investigated.

MK-8353 shows a tolerable safety profile and antitumor activity in melanoma patients with a BRAF-V600 mutation, rather than RAS mutation [137]. MK-8353 in combination with selumetinib or pembrolizumab is being investigated in patients with advanced malignancies, including CRC (Table 1). Although preclinical studies have shown that ERK mutations confer resistance to MAPK inhibitors [138], clinical studies have not yet reported the occurrence of acquired resistance to ERK inhibitors.

PI3K pathway inhibitors

Class I phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) is a lipid kinase that phosphorylates the signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), resulting in the recruitment of protein kinase B (PKB, best known as AKT) to the plasma membrane and subsequent activation of mTOR for cell growth and proliferation [139]. In contrast, PTEN, a tumor suppressor, can convert PIP3 to PIP2, thereby diminishing PI3K activity. PI3K consists of a catalytic subunit (p110, including p110α, p110β, p110γ, and p110δ isoforms) and a regulatory subunit (p85α or p85β). Compared with p110γ and p110δ, which are mainly expressed in immune cells, the expression of p110α and p110β is common in various cells or tissues. PIK3CA, which encodes p110α, is frequently mutated in cancer as an important drug target [139]. PIK3CA mutations can coexist with RAS mutations, while RAS mutations and MAPK pathway mutations are usually mutually exclusive [140, 141]. These co-mutation patterns might guide clinical trials to target different signals from the MAPK and PI3K pathways.

In May 2019, the FDA approved the first drug, alpelisib, as a specific p110α inhibitor for treating breast cancer. The combination of alpelisib with other chemotherapy (capecitabine or paclitaxel) is being tested in patients with PIK3CA-mutant CRC or gastric cancer patients (Table 1). The secondary p110α inhibitor GDC-0077 is under clinical development for the treatment of breast cancer (NCT04632992). Additionally, copanlisib (a pan class I PI3K inhibitor), duvelisib (a p110γ/p110δ inhibitor), and idelalisib (a p110δ inhibitor) are approved to treat adult patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, but not solid tumors, with RAS mutations. Despite considerable efforts to combine PI3K and MEK inhibitors in preclinical models [142], such a combination can cause significant toxicity in patients with RAS-mutated cancers [143, 144]. Similarly, the combination of AKT or mTOR inhibitors and MAPK inhibitors is generally poorly tolerated by patients, which may limit their applications [145, 146].

In summary, compared with MAPK pathway inhibitors, monotherapy or combination therapy with PI3K pathway inhibitors has limited benefits for patients with KRAS-mutated cancers, although such PI3K inhibitors may reverse resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors (discussed later). Current PI3K inhibitors are still challenged by insufficient selectivity, which results from the close structural resemblance among ATP binding sites of different PI3K isoforms [139].

Others

The MAPK and PI3K pathways activate transcription factors to induce or suppress the expression of genes involved in multiple cellular processes. Targeting related downstream processes (for example, autophagy, glycolysis, and immunosuppression) also may help to mitigate the carcinogenic activity of RAS but will not be discussed in this review. Of note, genomic screenings have enabled the discovery of synthetic lethal partners to inhibit tumor growth in KRAS-mutant cancer cells (Table 4).

Direct KRAS inhibition

Covalent KRAS-G12C inhibitors

Historically, KRAS was considered "undruggable" because it does not have a classical pocket suitable for binding small inhibitory molecules [18]. Recent structural studies and drug design efforts to produce G12Ci have changed this view (Table 5). The pioneering work of Shokat and colleagues uncovered a hidden pocket (switch-II) in the KRAS-GDP complex that is located next to the mutant cysteine 12 [172]. The proximity of switch-II to cysteine 12 facilitated the development of covalent inhibitors of switch-II, thereby achieving allosteric inhibition of cysteine 12 to prevent the nucleotide exchange catalyzed by GEF and diminish the subsequent interaction between RAS and RAF (Fig. 2c) [170, 172, 173]. Since wild-type KRAS lacks cysteine in the active site, the covalent inhibition of cysteine 12 is expected to be highly specific. ARS-1620 structurally modified from compound 12 [172], 1_AM [169], and ARS-853 [170] turned out to be the first G12Ci to elicit effective tumor suppression in patient-derived xenograft modes [171].

Amgen and Mirati Therapeutics developed two structure-optimized covalent G12Ci formulations, sotorasib [15] and adagrasib [16]. Compared with ARS-1620, sotorasib and adagrasib have larger surface grooves, which enhance the effectiveness of irreversible interactions with the H95 residue in the 3 helix of KRAS-G12C protein [15, 16]. Sotorasib and adagrasib mediate selective tumor suppression activity across a panel of cancer cell lines harboring the KRAS-G12C mutation [14, 16, 174]. Durable responses to sotorasib have been observed in immunocompetent rather than immunodeficient tumor-bearing mice [175]. This may be explained by the fact that sotorasib induces the production of chemokines (CXCL10 and CXCL11) and potential damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), leading to an immune response mediated by cytotoxic lymphocytes (Fig. 5) [175]. Accordingly, the combined use of anti–PD-1 antibodies further enhances sotorasib-induced tumor suppression in mouse models [175]. Whether G12Ci can be used to produce cancer-preventive or therapeutic immune responses is an open question. Interestingly, patient-derived xenograft models indicate that individual genetic alteration (such as in KRAS, TP53, STK11, or CDKN2A) cannot predict the anticancer activity of adagrasib [176]. CRISPR screens have identified negative (MYC, SHP2, mTOR, RPS6, CDK1, CDK2, CDK4/6, and RB1) and positive (KEAP1 and CBL) regulators of adagrasib sensitivity in NSCLC cells [176]. Drug screening further revealed that a pan-EGFR family inhibitor (afatinib), a SHP2 inhibitor (RMC-4550), mTOR inhibitors (vistusertib and everolimus), and a CDK4/6 inhibitor (palbociclib) increase the response rate to adagrasib in cell cultures and mouse models [176], providing potential optimization strategies for translational research.

Immunostimulation by sotorasib acting on the tumor microenvironment. Sotorasib is a highly selective inhibitor of KRAS-G12C that reacts with mutant cysteine at position 12 by connecting to a structural feature called the switch II pocket. Sotorasib can induce the production of chemokines, such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and CXCL11, as well as the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), leading to dendritic cell (DC) maturation and activation. The priming of naive T cells to generate cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) requires mature DC-mediated antigen presentation. The number and function of tumor-targeted CTLs is a prerequisite for the immune system to attack cancer cells. However, the expression of immune checkpoint substances (such as programmed cell death protein 1 [PD-1]) limit the anticancer activity of CTLs, and the administration of anti–PD-1 antibodies reverses this process

Clinical studies have shown some promising antitumor activity of sotorasib or adagrasib in patients with KRAS-G12C-mutated NSCLC that previously had been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and/or PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. In a phase II trial, 37.1% (46/124) of such NSCLC patients responded to single-agent sotorasib (900 mg/kg, once daily) with a median duration of response of 11.1 months across all PD-L1 expression level subgroups (Table 6) [178]. The activity of sotorasib has been observed in patients with mutations in TP53, STK11, and KEAP1 [178], which are associated with a poor prognosis in NSCLC [179]. Another phase I/II trial involved 129 KRAS-G12C–mutant cancer patients, in which 32.2% of NSCLC, 7.1% of CRC, and 14.3% of other tumor patients showed an objective response to sotorasib (Table 6) [177]. In May 2021, the FDA granted accelerated approval to sotorasib for the treatment of KRAS-G12C–mutated NSCLC. In June 2021, the FDA awarded breakthrough therapy designation to adagrasib for KRAS-G12C–mutated NSCLC based on an unpublished phase I/II study showing that 45% (23/51) of participants responded and 51% (26/51) of them were in stable conditions after using adagrasib (600 mg/kg, twice daily). Although the elimination half-lives of sotorasib (6 hours) and adagrasib (25 hours) are different, they have similar treatment-related adverse events (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting). A number of clinical trials are underway to evaluate the antitumor activity of sotorasib or adagrasib alone or in combination with target drugs (docetaxel, pembrolizumab, cetuximab, afatinib, or TNO155) in solid cancers carrying KRAS-G12C mutations (Table 1). Specifically, two phase III trials will test the combination of sotorasib or adagrasib with docetaxel or cetuximab to treat KRAS-G12C–mutant NSCLC or CRC, respectively (NCT04685135 and NCT04793958).

The clinical development of other G12Ci compounds, such as GDC-6036 and D-1553, might provide additional opportunities for selectively targeting advanced solid tumors with KRAS-G12C mutations (Table 1). Notably, the clinical trial of two G12Ci formulations, LY3499446 and JNJ-74699157, has been terminated due to significant toxicity (NCT04165031 and NCT04006301). It remains to be seen whether these toxicities are caused by covalent or noncovalent off-targets.

Pan-KRAS inhibitors

BI-2852 is a pan-KRAS inhibitor that binds between the switch-I and switch-II pockets, thereby blocking the interaction of KRAS protein with GEF, GAP, and its downstream effectors [180]. Early preclinical studies confirmed its activity in blocking the KRAS pathway in NSCLC cells [180]. Using FR054 to inhibit glycosylation reactions further enhances the anticancer activity of BI-2852 against PDAC cells [181], supporting that the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway is a potential target for the treatment of KRAS-mutant cancers [182].

Revolution Medicines utilized a tri-complex technology platform to design a type of RAS(ON) inhibitor. RAS(ON) inhibitors (for example, RM-007 and RM-008) act as molecular glues to mediate protein-protein interactions between different mutant KRAS proteins and an endogenous protein (cyclophilin), thereby inhibiting the binding of mutant KRAS to SOS1 and effector proteins. Thus, the mode of action of RAS(ON) inhibitors is different from that of RAS(OFF) inhibitors, including G12Ci.

More recently, a small-molecule compound called Pen-cRaf-v1 has been identified as a pan-RAS inhibitor capable of targeting G12C and non-G12C RAS mutants to inhibit RAS-effector interaction [183]. Further animal studies are needed to determine the activity, metabolism, and toxicity of pan-KRAS inhibitors before their translational application into clinical medicine.

Others

An interesting trend in recent drug discovery is the selective induction of protein degradation through the proteasome. Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology can be used to design new drugs that bridge the target protein to E3 ligases, hoping to achieve the target’s degradation to nonfunctional fragments. Whether this approach may be successful for the destruction of oncogenic RAS remains to be explored [184, 185].

Mechanisms of adaptation or resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors

Producing new KRAS-G12C protein

The activation of the EGFR-SHP2 pathway maintains newly synthesized KRAS-G12C protein in an active GTP-binding form, thereby leading to the adaptation of KRAS-G12C–mutated cancer cells to ARS-1620 (Fig. 6a) [186]. The cell cycle regulator aurora kinase A (AURKA) binds newly produced KRAS-G12C, which in turn stabilizes the interaction between CRAF and KRAS and mediates subsequent ERK effector signals for cell cycle progression [186]. Consequently, the inhibition of EGFR or AURKA reverses the adaptation of cancer cells to ARS-1620. These preclinical studies provide clues for the development of combined strategies that target EGFR or the cell cycle regulator to delay the development of resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors [186]. In addition to AURKA inhibitors (e.g., alisertib), many drugs that are already in clinical use or under development target various cell cycle regulators, especially CDKs. AURKA inhibitors and CDK inhibitors both have shown promise in the treatment of various types of cancer, including KRAS-mutant cancers [187,188,189,190,191,192].

Mechanisms of adaptation or resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors. a. Production of new KRAS-G12C protein. Activation of the pathway involving epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2)–SOS Ras/Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1 (SOS1) is necessary to maintain the newly produced KRAS-G12C protein in an active GTP-bound form, which leads to the adaptation of ARS-1620 through the RAF-MEK-extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. The cell cycle regulator aurora kinase A (AURKA) can further enhance KRAS-G12C–mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) effector pathways. b. Activating wild-type NRAS and HRAS. Multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), rather than a single RTK, activate wild-type NRAS and HRAS, leading to acquired resistance to ARS-1620 and sotorasib by the RAF-MEK-ERK and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT-mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. c. Inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR)-insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) pathway mediates PI3K activation in a SHP2-independent manner, leading to acquired resistance to sotorasib or ARS-1620 through snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1)-mediated EMT. d. Inducting secondary genetic alterations. An analysis of the genetic alterations of patients with acquired adagrasib resistance showed that 45% of the cases had a putative genetic mechanism of drug resistance. In short, acquired KRAS mutations in drug binding sites or oncogenic hotspots, gain-of-function mutations in the MAPK pathway, and loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes favor the acquisition of resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors

Activating wild-type RAS

Wild-type and mutant RAS subtypes co-exist in the same cell, thus providing a feedback mechanism to reactivate RAS signaling if one of the two RAS pathways is blocked. As such, even if KRAS-G12C is effectively and completely inhibited, residual wild-type RAS (NRAS and HRAS) activity may confer resistance to G12Ci. Multiple RTKs (EGFR, HER2, FGFR, and c-MET), instead of a single RTK, activate wild-type RAS, resulting in acquired resistance to ARS-1620 and sotoracide (Fig. 6b) [193]. This feedback reactivation of wild-type RAS occurs in parallel to the neosynthesis of KRAS-G12C protein, resulting in drug resistance. Since SHP2 and SOS1 are the common nodes of RTK signals, SHP2 inhibitors (e.g., TNO155, SHP099, and RMC-4550) or SOS1 inhibitors (e.g., BAY-293) may either enhance the activity of G12Ci or reverse adaptive resistance. This hypothesis has been confirmed in preclinical models [83, 116, 186, 193,194,195,196,197], and such inhibitors are now entering clinical evaluation (NCT04330664).

Inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the process whereby epithelial cells are transformed into mesenchymal cells, is one of the acquired resistance mechanisms to antineoplastic therapies, including TKIs [198]. The induction of EMT in sotorasib-sensitive NSCLC cells by adding TGFβ or using transfection with SNAIL leads to acquired resistance to sotorasib through the activation of the PI3K pathway, which is not associated with significant AKT activation [199]. This suggests that the classical KRAS-PI3K-AKT pathway is not essential for acquired resistance to sotorasib, whereas KRAS-independent PI3K activation favors such resistance in lung cancer cells [200]. In the latter, the insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR)-IRS1 pathway, as a key upstream signal, mediates PI3K activation in a SHP2-independent manner, leading to acquired resistance to sotorasib or ARS-1620 in NSCLC cells (Fig. 6c) [199]. Therefore, the clinical optimization of G12Ci may profit from patient stratification based on EMT status.

In other cases, the activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway clearly limits the efficacy of G12Ci, such as sotoracide or ARS1620, against NSCLC and PDAC cells [176, 201, 202]. Hence, the mechanisms of PI3K pathway-mediated resistance to G12Ci may depend on the tumor type and the degree of cellular (de)differentiation.

Inducing secondary genetic alterations

Specific secondary genetic alterations may provide additional information to predict G12Ci responses (Fig. 6d). Among 38 patients with KRAS-G12C-mutated solid cancers who received adagrasib monotherapy, 45% displayed a putative genetic mechanism for resistance [203]. The reactivation of RAS-MAPK signaling by 10 genetic alterations affecting the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway has been described in an NSCLC patient with acquired adagrasib resistance [204]. Secondary KRAS mutations, gain-of-function mutations of the MAPK pathway, loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes, gene fusion, and gene amplification are conducive to acquired resistance to G12Ci (Fig. 6d).

In vitro and in vivo, KRAS mutation studies further confirmed that the expression of clinically observed switch-II pocket mutations conferred resistance to adagrasib in KRAS-G12C–mutant BaF3 cells (a murine interleukin-3–dependent pro-B cell line) [203, 204]. Thus, the mutations Y96C, Y96D, or Y96S led to resistance to both adagrasib and sotorasib [203, 204]. In contrast, H95D, H95Q, and H95R mutants remained sensitive to sotorasib [203]. Interestingly, a RAS(ON) inhibitor retained its therapeutic index against cells harboring dual G12C/Y96D mutations [204], supporting the notion that RAS(ON) inhibitors mediate the inhibition of oncogenic RAS by a completely different mechanism.

Collectively, these studies provide proof of concept and mechanistic support for a combination therapy that suppresses adaptive genetic alterations. In fact, clinical trials evaluating adagrasib or sotorasib in combination with inhibitors of RTKs, MAPK, SOS1, or SHP2 are underway (NCT04330664 and NCT04185883) to explore novel strategies for overcoming cancer drug resistance [79, 205].

Conclusions and future perspectives

With the development of G12Ci, we now have a tool to directly and irreversibly inhibit KRAS-G12C oncoprotein in patients [17]. However, the excitement spurred by this discovery has been dampened by the fact that the vast majority of patients fail to respond to G12Ci treatment due to primary or acquired resistance [177, 203, 204, 206]. Thus, there are still many outstanding problems to be solved.

First, how can we develop next-generation inhibitors?

Different G12Ci compounds exhibit distinct activities and toxicities. For example, adagrasib was found to bind to KRAS-G12C equally in a series of different cell lines, despite the major variability in downstream signals [176]. The main risk of covalent inhibitors is the possibility of nonspecific reactions with off-target proteins containing cysteine residues [173]. Thus, the molecular identification of proteins accounting for off-target effects of G12Ci may improve structure-based drug design [203]. In addition to organ-mediated drug metabolism, tumor-resident microorganisms can directly decompose chemotherapeutic drugs to cause drug resistance [207]. Hence, optimizing the in vivo pharmacokinetic properties of KRAS inhibitors and evaluating the (in)activity of their metabolites is still an important area for examination. Finally, it remains to be seen whether it is possible to develop additional mutation-specific inhibitors or pan-mutant KRAS inhibitors [208].

Second, how can we design combination therapies?

The design and implementation of strategies to minimize or overcome drug resistance is an important goal of clinical oncology in order to achieve complete and durable clinical responses [209]. The observed tumor heterogeneity and the extensive feedback between RAS and other tumor-related signals may promote drug resistance. The combination of several drugs intercepting different signaling pathways (e.g., upstream signaling, downstream signaling, parallel signaling, cell cycle processes, or immune checkpoints) may prevent or delay the development of therapy resistance, but usually at the cost of increased toxicity [14, 17]. A number of clinical trials combining G12Ci with other established agents (including TKIs and ICIs) are being launched. The design of such trials should avoid random combinations and follow a rationale based on the genetic, metabolic, and immune mechanisms of drug resistance.

Third, how can we develop predictive cancer biomarkers?

Predictive biomarkers can guide treatment decisions by indicating the likely impact of a particular therapy on a patient. Some genetic alterations, especially secondary gene mutation, are associated with the development of adagrasib resistance in patients. In addition to using endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration, the analysis of circulating tumor DNA combined with next-generation sequencing technologies provides a way for examining the genetic characteristics of tumors. Despite these obvious technological advances, circulating metabolites or proteins should not be neglected as potential biomarkers, given that their quantitation would be much more convenient.

In summary, the development of ever more efficient and specific drugs blocking oncogenic RAS must be in parallel with major efforts to avoid and overcome therapeutic resistance. Given the continued efforts of industry, academia, and health care providers, as well as the latest breakthroughs in basic, clinical, and translational research on G12Ci, the prospects look bright.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Harvey JJ. An Unidentified Virus Which Causes the Rapid Production of Tumours in Mice. Nature. 1964;204:1104–5.

Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The Frequency of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80(14):2969–74.

Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–65.

Johnson L, Greenbaum D, Cichowski K, Mercer K, Murphy E, Schmitt E, et al. K-ras is an essential gene in the mouse with partial functional overlap with N-ras. Genes Dev. 1997;11(19):2468–81.

Shimizu K, Goldfarb M, Suard Y, Perucho M, Li Y, Kamata T, et al. Three human transforming genes are related to the viral ras oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(8):2112–6.

Shimizu K, Birnbaum D, Ruley MA, Fasano O, Suard Y, Edlund L, et al. Structure of the Ki-ras gene of the human lung carcinoma cell line Calu-1. Nature. 1983;304(5926):497–500.

Santos E, Martin-Zanca D, Reddy EP, Pierotti MA, Della Porta G, Barbacid M. Malignant activation of a K-ras oncogene in lung carcinoma but not in normal tissue of the same patient. Science. 1984;223(4637):661–4.

Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Presence of a Kirsten murine sarcoma virus ras oncogene in cells transformed by 3-methylcholanthrene. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3(12):2298–301.

Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Tuveson DA, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1111–6.

Sukumar S, Notario V, Martin-Zanca D, Barbacid M. Induction of mammary carcinomas in rats by nitroso-methylurea involves malignant activation of H-ras-1 locus by single point mutations. Nature. 1983;306(5944):658–61.

Chen X, Mitsutake N, LaPerle K, Akeno N, Zanzonico P, Longo VA, et al. Endogenous expression of Hras(G12V) induces developmental defects and neoplasms with copy number imbalances of the oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(19):7979–84.

Burd CE, Liu W, Huynh MV, Waqas MA, Gillahan JE, Clark KS, et al. Mutation-specific RAS oncogenicity explains NRAS codon 61 selection in melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(12):1418–29.

Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(11):761–74.

Moore AR, Rosenberg SC, McCormick F, Malek S. RAS-targeted therapies: is the undruggable drugged? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(8):533–52.

Lanman BA, Allen JR, Allen JG, Amegadzie AK, Ashton KS, Booker SK, et al. Discovery of a Covalent Inhibitor of KRAS(G12C) (AMG 510) for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. J Med Chem. 2020;63(1):52–65.

Fell JB, Fischer JP, Baer BR, Blake JF, Bouhana K, Briere DM, et al. Identification of the Clinical Development Candidate MRTX849, a Covalent KRAS(G12C) Inhibitor for the Treatment of Cancer. J Med Chem. 2020;63(13):6679–93.

Kim D, Xue JY, Lito P. Targeting KRAS(G12C): From Inhibitory Mechanism to Modulation of Antitumor Effects in Patients. Cell. 2020;183(4):850–9.

Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(11):828–51.

Murugan AK, Grieco M, Tsuchida N. RAS mutations in human cancers: Roles in precision medicine. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;59:23–35.

Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72(10):2457–67.

Li S, Balmain A, Counter CM. A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: finding the sweet spot. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(12):767–77.

Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1114–7.

Zhang J, Fujimoto J, Zhang J, Wedge DC, Song X, Zhang J, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung adenocarcinomas delineated by multiregion sequencing. Science. 2014;346(6206):256–9.

Cook JH, Melloni GEM, Gulhan DC, Park PJ, Haigis KM. The origins and genetic interactions of KRAS mutations are allele- and tissue-specific. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1808.

Zhang X, Cao J, Miller SP, Jing H, Lin H. Comparative Nucleotide-Dependent Interactome Analysis Reveals Shared and Differential Properties of KRas4a and KRas4b. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4(1):71–80.

Tsai FD, Lopes MS, Zhou M, Court H, Ponce O, Fiordalisi JJ, et al. K-Ras4A splice variant is widely expressed in cancer and uses a hybrid membrane-targeting motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(3):779–84.

Amendola CR, Mahaffey JP, Parker SJ, Ahearn IM, Chen WC, Zhou M, et al. KRAS4A directly regulates hexokinase 1. Nature. 2019;576(7787):482–6.

Plowman SJ, Williamson DJ, O'Sullivan MJ, Doig J, Ritchie AM, Harrison DJ, et al. While K-ras is essential for mouse development, expression of the K-ras 4A splice variant is dispensable. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(24):9245–50.

Haigis KM. KRAS Alleles: The Devil Is in the Detail. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(10):686–97.

Slebos RJ, Kibbelaar RE, Dalesio O, Kooistra A, Stam J, Meijer CJ, et al. K-ras oncogene activation as a prognostic marker in adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(9):561–5.

Pan W, Yang Y, Zhu H, Zhang Y, Zhou R, Sun X. KRAS mutation is a weak, but valid predictor for poor prognosis and treatment outcomes in NSCLC: A meta-analysis of 41 studies. Oncotarget. 2016;7(7):8373–88.

Shepherd FA, Domerg C, Hainaut P, Janne PA, Pignon JP, Graziano S, et al. Pooled analysis of the prognostic and predictive effects of KRAS mutation status and KRAS mutation subtype in early-stage resected non-small-cell lung cancer in four trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2173–81.

Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, Mok T, Socinski MA, Gervais R, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):744–52.

Zhu CQ, da Cunha SG, Ding K, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Liu N, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4268–75.

Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, Xavier AC, Ozburn NC, Liu DD, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(10):2890–6.

Hames ML, Chen H, Iams W, Aston J, Lovly CM, Horn L. Correlation between KRAS mutation status and response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2016;92:29–34.

Kim JH, Kim HS, Kim BJ. Prognostic value of KRAS mutation in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis and review. Oncotarget. 2017;8(29):48248–52.

Jeanson A, Tomasini P, Souquet-Bressand M, Brandone N, Boucekine M, Grangeon M, et al. Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(6):1095–101.

Sun L, Hsu M, Cohen RB, Langer CJ, Mamtani R, Aggarwal C. Association Between KRAS Variant Status and Outcomes With First-line Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Based Therapy in Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):937–9.

Kartolo A, Feilotter H, Hopman W, Fung AS, Robinson A. A single institution study evaluating outcomes of PD-L1 high KRAS-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with first line immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;27:100330.

Nardo G, Carlet J, Marra L, Bonanno L, Boscolo A, Dal Maso A, et al. Detection of Low-Frequency KRAS Mutations in cfDNA From EGFR-Mutated NSCLC Patients After First-Line EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Front Oncol. 2020;10:607840.

Bournet B, Muscari F, Buscail C, Assenat E, Barthet M, Hammel P, et al. KRAS G12D Mutation Subtype Is A Prognostic Factor for Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e157.

Heinemann V, Vehling-Kaiser U, Waldschmidt D, Kettner E, Marten A, Winkelmann C, et al. Gemcitabine plus erlotinib followed by capecitabine versus capecitabine plus erlotinib followed by gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: final results of a randomised phase 3 trial of the 'Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie' (AIO-PK0104). Gut. 2013;62(5):751–9.

Qian ZR, Rubinson DA, Nowak JA, Morales-Oyarvide V, Dunne RF, Kozak MM, et al. Association of Alterations in Main Driver Genes With Outcomes of Patients With Resected Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):e173420.

Ako S, Nouso K, Kinugasa H, Dohi C, Matushita H, Mizukawa S, et al. Utility of serum DNA as a marker for KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer tissue. Pancreatology. 2017;17(2):285–90.

Cheng H, Liu C, Jiang J, Luo G, Lu Y, Jin K, et al. Analysis of ctDNA to predict prognosis and monitor treatment responses in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(10):2344–50.

Cheng H, Luo G, Jin K, Fan Z, Huang Q, Gong Y, et al. Kras mutation correlating with circulating regulatory T cells predicts the prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2020;9(6):2153–9.

Haas M, Ormanns S, Baechmann S, Remold A, Kruger S, Westphalen CB, et al. Extended RAS analysis and correlation with overall survival in advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(11):1462–9.

Schultheis B, Reuter D, Ebert MP, Siveke J, Kerkhoff A, Berdel WE, et al. Gemcitabine combined with the monoclonal antibody nimotuzumab is an active first-line regimen in KRAS wildtype patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter, randomized phase IIb study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2429–35.

Boeck S, Jung A, Laubender RP, Neumann J, Egg R, Goritschan C, et al. KRAS mutation status is not predictive for objective response to anti-EGFR treatment with erlotinib in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(4):544–8.

Perets R, Greenberg O, Shentzer T, Semenisty V, Epelbaum R, Bick T, et al. Mutant KRAS Circulating Tumor DNA Is an Accurate Tool for Pancreatic Cancer Monitoring. Oncologist. 2018;23(5):566–72.

Del Re M, Vivaldi C, Rofi E, Vasile E, Miccoli M, Caparello C, et al. Early changes in plasma DNA levels of mutant KRAS as a sensitive marker of response to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7931.

Watanabe F, Suzuki K, Tamaki S, Abe I, Endo Y, Takayama Y, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of KRAS-mutated circulating tumor DNA enables the prediction of prognosis and therapeutic responses in patients with pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0227366.

Ogura T, Yamao K, Hara K, Mizuno N, Hijioka S, Imaoka H, et al. Prognostic value of K-ras mutation status and subtypes in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration specimens from patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(5):640–6.

Cerottini JP, Caplin S, Saraga E, Givel JC, Benhattar J. The type of K-ras mutation determines prognosis in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;175(3):198–202.

Yoon HH, Tougeron D, Shi Q, Alberts SR, Mahoney MR, Nelson GD, et al. KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in relation to disease-free survival in BRAF-wild-type stage III colon cancers from an adjuvant chemotherapy trial (N0147 alliance). Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(11):3033–43.

Taieb J, Zaanan A, Le Malicot K, Julie C, Blons H, Mineur L, et al. Prognostic Effect of BRAF and KRAS Mutations in Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Treated With Leucovorin, Fluorouracil, and Oxaliplatin With or Without Cetuximab: A Post Hoc Analysis of the PETACC-8 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):643–53.

Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Oates JR, Clarke PA. Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the multicenter "RASCAL" study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(9):675–84.

Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):466–74.

Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Freeman DJ, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1626–34.

De Roock W, Piessevaux H, De Schutter J, Janssens M, De Hertogh G, Personeni N, et al. KRAS wild-type state predicts survival and is associated to early radiological response in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(3):508–15.

Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–65.

Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):1023–34.

Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M, Sartorius U, Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E. Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(29):3570–7.

De Roock W, Jonker DJ, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Tu D, Siena S, et al. Association of KRAS p.G13D mutation with outcome in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1812–20.

Liao W, Overman MJ, Boutin AT, Shang X, Zhao D, Dey P, et al. KRAS-IRF2 Axis Drives Immune Suppression and Immune Therapy Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(4):559–72 e7.

Ahn E, Kang H. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2018;71(2):103–12.

Hancock JF. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(5):373–84.

Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):269–309.

Xu GF, O'Connell P, Viskochil D, Cawthon R, Robertson M, Culver M, et al. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell. 1990;62(3):599–608.

Trahey M, McCormick F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science. 1987;238(4826):542–5.

Bonfini L, Karlovich CA, Dasgupta C, Banerjee U. The Son of sevenless gene product: a putative activator of Ras. Science. 1992;255(5044):603–6.

Buday L, Downward J. Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell. 1993;73(3):611–20.

Ebinu JO, Bottorff DA, Chan EY, Stang SL, Dunn RJ, Stone JC. RasGRP, a Ras guanyl nucleotide- releasing protein with calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding motifs. Science. 1998;280(5366):1082–6.

Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell. 2017;170(1):17–33.

Hunter JC, Manandhar A, Carrasco MA, Gurbani D, Gondi S, Westover KD. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of Common Cancer-Associated KRAS Mutations. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13(9):1325–35.

Egan SE, Giddings BW, Brooks MW, Buday L, Sizeland AM, Weinberg RA. Association of Sos Ras exchange protein with Grb2 is implicated in tyrosine kinase signal transduction and transformation. Nature. 1993;363(6424):45–51.

Gale NW, Kaplan S, Lowenstein EJ, Schlessinger J, Bar-Sagi D. Grb2 mediates the EGF-dependent activation of guanine nucleotide exchange on Ras. Nature. 1993;363(6424):88–92.

Hofmann MH, Gmachl M, Ramharter J, Savarese F, Gerlach D, Marszalek JR, et al. BI-3406, a Potent and Selective SOS1-KRAS Interaction Inhibitor, Is Effective in KRAS-Driven Cancers through Combined MEK Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(1):142–57.

Mainardi S, Mulero-Sanchez A, Prahallad A, Germano G, Bosma A, Krimpenfort P, et al. SHP2 is required for growth of KRAS-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer in vivo. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):961–7.

Ruess DA, Heynen GJ, Ciecielski KJ, Ai J, Berninger A, Kabacaoglu D, et al. Mutant KRAS-driven cancers depend on PTPN11/SHP2 phosphatase. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):954–60.

Wong GS, Zhou J, Liu JB, Wu Z, Xu X, Li T, et al. Targeting wild-type KRAS-amplified gastroesophageal cancer through combined MEK and SHP2 inhibition. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):968–77.

Hillig RC, Sautier B, Schroeder J, Moosmayer D, Hilpmann A, Stegmann CM, et al. Discovery of potent SOS1 inhibitors that block RAS activation via disruption of the RAS-SOS1 interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(7):2551–60.

Lin CC, Wieteska L, Suen KM, Kalverda AP, Ahmed Z, Ladbury JE. Grb2 binding induces phosphorylation-independent activation of Shp2. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):437.

Sigismund S, Avanzato D, Lanzetti L. Emerging functions of the EGFR in cancer. Mol Oncol. 2018;12(1):3–20.

Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Allen LF, Lefkowitz RJ. Direct evidence that Gi-coupled receptor stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase is mediated by G beta gamma activation of p21ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(26):12706–10.

Wan Y, Kurosaki T, Huang XY. Tyrosine kinases in activation of the MAP kinase cascade by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 1996;380(6574):541–4.

Vanhaesebroeck B, Perry MWD, Brown JR, Andre F, Okkenhaug K. PI3K inhibitors are finally coming of age. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00209-1. Online ahead of print.

Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C, Drula R, Gulei D, Raduly L, et al. A Comprehensive Review on MAPK: A Promising Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1618.

Uprety D, Adjei AA. KRAS: From undruggable to a druggable Cancer Target. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;89:102070.

Hu Y, Lu W, Chen G, Wang P, Chen Z, Zhou Y, et al. K-ras(G12V) transformation leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and a metabolic switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. Cell Res. 2012;22(2):399–412.

Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Kroemer G, Klionsky DJ, et al. Autophagy-Dependent Ferroptosis Drives Tumor-Associated Macrophage Polarization via Release and Uptake of Oncogenic KRAS Protein. Autophagy. 2020;16(11):2069–83.

Carriere C, Young AL, Gunn JR, Longnecker DS, Korc M. Acute pancreatitis markedly accelerates pancreatic cancer progression in mice expressing oncogenic Kras. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382(3):561–5.

Philip B, Roland CL, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Chatterjee D, Gomez SB, et al. A high-fat diet activates oncogenic Kras and COX2 to induce development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1449–58.

Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Zeh HJ, Kang R, et al. Ferroptotic damage promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis through a TMEM173/STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6339.

Ross SJ, Revenko AS, Hanson LL, Ellston R, Staniszewska A, Whalley N, et al. Targeting KRAS-dependent tumors with AZD4785, a high-affinity therapeutic antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of KRAS. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(394):eaal5253.

Sacco A, Federico C, Todoerti K, Ziccheddu B, Palermo V, Giacomini A, et al. Specific targeting of the KRAS mutational landscape in myeloma as a tool to unveil the elicited anti-tumor activity. Blood. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020010572. Online ahead of print.

Golan T, Khvalevsky EZ, Hubert A, Gabai RM, Hen N, Segal A, et al. RNAi therapy targeting KRAS in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):24560–70.

Berndt N, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. Targeting protein prenylation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(11):775–91.

Cohen SJ, Ho L, Ranganathan S, Abbruzzese JL, Alpaugh RK, Beard M, et al. Phase II and pharmacodynamic study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 as initial therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1301–6.

Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawlowski A, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1430–8.

Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG, O'Bryant CL, Schultz MK, Morrow M, Grolnic S, et al. A phase I safety, pharmacological, and biological study of the farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor, lonafarnib (SCH 663366), in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62(4):631–46.

Sharma S, Kemeny N, Kelsen DP, Ilson D, O'Reilly E, Zaknoen S, et al. A phase II trial of farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor SCH 66336, given by twice-daily oral administration, in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(7):1067–71.

Whyte DB, Kirschmeier P, Hockenberry TN, Nunez-Oliva I, James L, Catino JJ, et al. K- and N-Ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein transferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(22):14459–64.

Kazi A, Xiang S, Yang H, Chen L, Kennedy P, Ayaz M, et al. Dual Farnesyl and Geranylgeranyl Transferase Inhibitor Thwarts Mutant KRAS-Driven Patient-Derived Pancreatic Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5984–96.

Manu KA, Chai TF, Teh JT, Zhu WL, Casey PJ, Wang M. Inhibition of Isoprenylcysteine Carboxylmethyltransferase Induces Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis through p21 and p21-Regulated BNIP3 Induction in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(5):914–23.

Spencer-Smith R, Koide A, Zhou Y, Eguchi RR, Sha F, Gajwani P, et al. Inhibition of RAS function through targeting an allosteric regulatory site. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):62–8.

Ayati A, Moghimi S, Salarinejad S, Safavi M, Pouramiri B, Foroumadi A. A review on progression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors as an efficient approach in cancer targeted therapy. Bioorg Chem. 2020;99:103811.

Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):786–92.

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):1960–6.

Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S, Scala E, Janakiraman M, Liska D, et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature. 2012;486(7404):532–6.

Cai D, Choi PS, Gelbard M, Meyerson M. Identification and Characterization of Oncogenic SOS1 Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(4):1002–12.

Chen YN, LaMarche MJ, Chan HM, Fekkes P, Garcia-Fortanet J, Acker MG, et al. Allosteric inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase inhibits cancers driven by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature. 2016;535(7610):148–52.

Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, Hashimoto-Tane A, Azuma M, Saito T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209(6):1201–17.

LaMarche MJ, Acker M, Argintaru A, Bauer D, Boisclair J, Chan H, et al. Identification of TNO155, an Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Cancer. J Med Chem. 2020;63(22):13578–94.

Liu C, Lu H, Wang H, Loo A, Zhang X, Yang G, et al. Combinations with Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitor TNO155 to Block Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(1):342–54.

Yen I, Shanahan F, Lee J, Hong YS, Shin SJ, Moore AR, et al. ARAF mutations confer resistance to the RAF inhibitor belvarafenib in melanoma. Nature. 2021;594(7863):418–23.

Park S, Kim TM, Cho SY, Kim S, Oh Y, Kim M, et al. Combined blockade of polo-like kinase and pan-RAF is effective against NRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2020;495:135–44.

Monaco KA, Delach S, Yuan J, Mishina Y, Fordjour P, Labrot E, et al. LXH254, a Potent and Selective ARAF-Sparing Inhibitor of BRAF and CRAF for the Treatment of MAPK-Driven Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(7):2061–73.

Desai J, Gan H, Barrow C, Jameson M, Atkinson V, Haydon A, et al. Phase I, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation/Dose-Expansion Study of Lifirafenib (BGB-283), an RAF Family Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(19):2140–50.

Yuan X, Tang Z, Du R, Yao Z, Cheung SH, Zhang X, et al. RAF dimer inhibition enhances the antitumor activity of MEK inhibitors in K-RAS mutant tumors. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(8):1833–49.

Janne PA, van den Heuvel MM, Barlesi F, Cobo M, Mazieres J, Crino L, et al. Selumetinib Plus Docetaxel Compared With Docetaxel Alone and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With KRAS-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The SELECT-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1844–53.

Blumenschein GR Jr, Smit EF, Planchard D, Kim DW, Cadranel J, De Pas T, et al. A randomized phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) compared with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)dagger. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):894–901.

Bodoky G, Timcheva C, Spigel DR, La Stella PJ, Ciuleanu TE, Pover G, et al. A phase II open-label randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244 [ARRY-142886]) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who have failed first-line gemcitabine therapy. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30(3):1216–23.

Bennouna J, Lang I, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Boer K, Adenis A, Escudero P, et al. A Phase II, open-label, randomised study to assess the efficacy and safety of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus capecitabine monotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. Investig New Drugs. 2011;29(5):1021–8.

Yen I, Shanahan F, Merchant M, Orr C, Hunsaker T, Durk M, et al. Pharmacological Induction of RAS-GTP Confers RAF Inhibitor Sensitivity in KRAS Mutant Tumors. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(4):611–25 e7.

Lebbe C, Italiano A, Houede N, Awada A, Aftimos P, Lesimple T, et al. Selective Oral MEK1/2 Inhibitor Pimasertib in Metastatic Melanoma: Antitumor Activity in a Phase I, Dose-Escalation Trial. Target Oncol. 2021;16(1):47–57.