Abstract

Purpose and method

Necrotizing tracheobronchitis is a rare clinical entity presented as a necrotic inflammation involving the mainstem trachea and distal bronchi. We reported a case of severe necrotizing tracheobronchitis caused by influenza B and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) co-infection in an immunocompetent patient.

Case presentation

We described a 36-year-old man with initial symptoms of cough, rigors, muscle soreness and fever. His status rapidly deteriorated two days later and he was intubated. Bronchoscopy demonstrated severe necrotizing tracheobronchitis, and CT imaging demonstrated multiple patchy and cavitation formation in both lungs. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) culture supported the co-infection of influenza B and MRSA. We also found T lymphocyte and NK lymphocyte functions were extremely suppressed during illness exacerbation. The patient was treated with antivirals and antibiotics including vancomycin. Subsequent bronchoscopy and CT scans revealed significant improvement of the airway and pulmonary lesions, and the lymphocyte functions were restored. Finally, this patient was discharged successfully.

Conclusion

Necrotizing tracheobronchitis should be suspected in patients with rapid deterioration after influenza B infection. The timely diagnosis of co-infection and accurate antibiotics are important to effective treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Necrotizing tracheobronchitis is a rare clinical entity presented as a necrotic inflammation involving the mainstem trachea and distal bronchi. Most necrotizing tracheobronchitis is usually developed in patients with immunocompromised conditions, like long term mechanical ventilation [1], low birth weight infant [2], metastatic carcinoma or use of immunosuppressants [3]. However, especially in immunocompetent patients, necrotizing tracheobronchitis associated with influenza is very rare. Most of the published cases reported the necrotizing tracheobronchitis with influenza A only [4], or the complication of influenza A with bacterial co-infection [5,6,7]. There are few reported instances of co-infection involving other types of influenza and bacteria in necrotizing tracheobronchitis. Here we report a case of necrotizing tracheobronchitis caused by influenza B and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) co-infection in an immunocompetent patient.

Case report

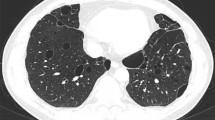

A 36-year-old man with no underlying history or tobacco use presented to the emergency department of local hospital with 3-days history of cough, rigors, muscle soreness and fever. Vital signs: blood pressure (BP) 133/75 mmHg, pulse rate (PR) 105 beats per minute, respiratory rate (RR) 19 breaths per minute, temperature (T) 39.0 °C, and SpO2 97% on air. Rapid influenza test using colloidal gold assay was positive for influenza B. Routine blood test showed normal white blood cell (WBC) count with neutrophils 74.6%, but decreased lymphocyte of 0.63 × 109/L (normal range 1.10 × 109/L − 3.20 × 109/L). Empiric ibuprofen and oseltamivir were started. However, the symptoms aggravated with dyspnea and chest pain. The patient presented to the emergency department 2 days later. Vital signs: BP 122/86 mmHg, PR 132 beats per minute, RR 37 breaths per minute, T 37.5 °C, and SpO2 78% on air. Coarse breathing sounds were noted in both lung fields on auscultation. He was admitted, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of the throat swabs confirmed the influenza B infection. Laboratory tests showed: WBC 5.87 × 109/L, neutrophils 80.7%, platelet 118 × 109/L, lymphocyte 0.41 × 109/L, creatinine 88 umol/L, blood urea nitrogen 4.96 mmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 25 IU/L, total bilirubin 37.8 umol/L, direct bilirubin 7.8 umol/L, procalcitonin 5.33 ng/mL, lactate 1.9 mmol/L, respectively. The proBNP and cTNI levels were normal. Arterial blood gas showed pH 7.52, PCO2 33 mm Hg, PO2 60 mm Hg, and bicarbonate 28.1 mmol/L on mask of 10 L/min oxygen. Invasive mechanical ventilation was needed 4 h after admission due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and was started on imipenem 2.0 g q6h, moxifloxacin 0.4 g qd, Baloxavir marboxil 40 mg qd, methylprednisolone, and prone position ventilation. Bronchoscopy showed severe hemorrhagic tracheobronchitis involving the mainstem trachea and distal bronchi with sloughing and diffuse mucosal swelling (Fig. 1A). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was sent for next-generation sequencing (NGS) and culture. Staphylococcus aureus (homogenized sequence 11,597, 3,134,324 copies/mL) and influenza B (homogenized sequence 25, 6757 copies/mL) were detected from NGS, and other bacteria, fungi, and parasites were not detected. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which was susceptible to vancomycin, linezolid, and teicoplanin by drug sensitivity test, was isolated from the culture. BALF Gram stain showed Gram positive cocci phagocytosed by white blood cells (Fig. 2). Chest computed tomography (CT) and plain chest radiographs demonstrated patchy consolidations and multifocal nodular opacities with cavitations in both lungs (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Consecutive multiple sputum specimens yielded the same cultures of MRSA. The imipenem was de-escalated to piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g q8h, and moxifloxacin was switched to vancomycin 1.0 g q12h after the NGS reports on the 3rd day after admission, with the maintenance of other treatment plans. Bronchoscopy showed much improvement during follow-up (Fig. 1B-D). The methylprednisolone was stopped on the 4th day after admission; the patient was extubated on the 7th day after admission; Baloxavir marboxil and piperacillin/tazobactam was stopped on the 8th day after admission; Vancomycin was switched to oral linezolid on the 9th day after admission. Finally, he was discharged to home on the 15th day after admission. The patient’s lymphocyte count was followed until discharge, and lymphocyte subsets were measured using the FACSCanto Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). In lymphocyte subsets, CD3 + CD8 + T cell, CD3 + CD4 + T cell, and CD3-CD16+/56 + NK cell counts are extremely low on the 3rd day after admission (Table 1). After antibiotics adjustment focusing on MRSA, these indices gradually recovered and restored to normal range on the 12th day after admission.

Follow-up bronchoscopy. (A) Severe hemorrhagic tracheobronchitis involving the mainstem trachea and distal bronchi with sloughing and diffuse mucosal swelling observed on the 2nd day after admission. (B) Severe mucosal inflammation and purulent secretion were observed on the 3rd day after admission. (C) Inflammatory mucosal change with reduced secretion on the 4th day after admission, one day after switching to vancomycin. (D) The affected mucosa resolved on the 7th day after admission, four days after switching to vancomycin. Carina (black star)

Chest computed tomography images. (A) Patchy consolidations in both lungs observed on the 1st day after admission. (B) Multifocal nodular opacities with new cavitations in left lung (blue arrow) and right lung (red arrow) observed on the 8th day after admission. (C) Residual cavitations in left lung (blue arrow) and enlarged cavitations in right lung (red arrow) observed on the 15th day after admission (discharge). (D) Resolved cavitations in left lung and resolved patchy consolidations with residual cavitations in right lung (red arrow) observed on the 4th day after discharge. (E) Resolved cavitations in both lungs observed 1 month later after discharge

Plain chest radiographs. (A) On the 1st day after admission. (B) On the 4th day after admission. (C) Multiple small cavitations in nodular opacities in right upper lung (black arrow) observed on the 8th day after admission. (D) A large cavitation formed in right upper lung (black arrow) observed on the 15th day after admission (discharge). (E) one month later after discharge

Discussion

Influenza virus infection is mainly prevalent in the winter season. Mostly, the symptoms are self-limiting and mild, but influenza can also lead to life threatening pneumonia and ARDS. There are several influenza A pandemics in history [8]. However, the awareness of influenza B infection is less than influenza A due to its lack of pandemic potential. Infections caused by Influenza B were previously believed to lead to a milder severity than influenza A, but the published data suggest that the rate of mortality may be similar between these two influenza types in the overall population [9].

Necrotizing tracheobronchitis is a rare complication usually presumed to be caused by a non-infectious origin, or a secondary bacterial infection following a primary viral respiratory infection. It has been reported in autopsy studies involving pandemic 1918 H1N1 and pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza patients [10, 11]. Co-infection with bacteria commonly occurs in critically ill patients infected with influenza. Necrotizing tracheobronchitis due to co-infection of the influenza A virus and MRSA has been reported in several cases [5,6,7, 12]. Unlike these previous cases, there are few reported instances of co-infection involving other types of influenza and bacteria. Only one case reported co-infection of the influenza B virus and MRSA in an old man with a history of chronic diseases [13]. Complication rates in influenza infection are highest in patients with underlying chronic diseases, immunosuppressed status, or older subjects. However, no predisposing factors could be identified. Interestingly, in all the previously reported necrotizing tracheobronchitis cases following the influenza infection in immunocompetent patients, including in this case, Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly detected co-infection bacteria. It has been well known that culturing positive rate of Staphylococcus aureus is high in critically ill patients infected with influenza, and is associated with an increased risk of death [14]. It is still unexplained why the complication rate of necrotizing tracheobronchitis is high in influenza and Staphylococcus aureus co-infection. In previous reports, the reasons may be the toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) or panton-valentine leukocidin (PVL) expressed by some hypervirulent Staphylococcus aureus strains [7, 15]. Lymphocyte function is very important in host defense against pathogenic microorganism. In this case, the lymphocyte subsets may indicate the attenuated T lymphocyte and NK lymphocyte functions by the synergy of influenza and Staphylococcus aureus, which is supported by published studies [16, 17].

In this case, early empirical antiviral treatment and antibiotic treatment with anti-Gram negative antibiotic combined with anti-Gram positive antibiotic was administered when this patient was suspected of co-infection. Empirical using of vancomycin or linezolid should be considered in patients suspected of Gram positive cocci infection. It is recommended that antibiotics regimen should be changed according to the culture results of high-quality respiratory specimens. In this case, intravenous vancomycin has a significant clinical effect in the treatment of MRSA tracheobronchitis.

In conclusion, here we report a young immunocompetent patient with severe necrotizing tracheobronchitis caused by influenza B and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus co-infection. Particularly, we find T lymphocyte and NK lymphocyte functions are extremely suppressed during illness exacerbation. Necrotizing tracheobronchitis should be suspected in patients with rapid deterioration after influenza B infection. The timely diagnosis of co-infection and accurate antibiotics are important to effective treatment.

Data availability

All relevant data has been presented in the manuscript and further inquiry can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Cho JY, Kim Y, Lee SH, et al. Bronchoscopic improvement of Tracheobronchitis due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus after Aerosolized Vancomycin: a Case Series. J Aerosol Med Pulmonary drug Delivery. 2018;31:372–5.

Hasegawa H, Nagase Y, Sakai M, et al. Tracheoplasty using the thymus against tracheo-esophageal fistula due to necrotizing tracheobronchitis in a very low birth weight infant. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:E135–139.

Nakatsumi H, Watanabe S, Gohara K et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Necrotizing Bronchitis after Radiotherapy in Combination with Axitinib. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2022; 61:2931–4.

Chang J, Kim TO, Yoon JY, et al. Necrotizing tracheobronchitis causing airway obstruction complicated by pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza: a case report. Med (Baltim). 2020;99:e18647.

Park SS, Kim SH, Kim M, et al. A case of severe pseudomembranous Tracheobronchitis complicated by co-infection of Influenza A (H1N1) and Staphylococcus aureus in an Immunocompetent patient. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2015;78:366–70.

Tsokos M, Zollner B, Feucht HH. Fatal influenza a infection with Staphylococcus aureus superinfection in a 49-year-old woman presenting as sudden death. Int J Legal Med. 2005;119:40–3.

Gabrilovich MI, Huff MD, McMillen SM, et al. Severe necrotizing Tracheobronchitis from Panton-Valentine Leukocidin-positive MRSA Pneumonia Complicating Influenza A-H1N1-09. J Bronchol Interventional Pulmonol. 2017;24:63–6.

Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Hampson AW. The epidemiology and clinical impact of pandemic influenza. Vaccine. 2003;21:1762–8.

Su S, Chaves SS, Perez A, et al. Comparing clinical characteristics between hospitalized adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza A and B virus infection. Clin Infect Diseases: Official Publication Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59:252–5.

Kuiken T, Taubenberger JK. Pathology of human influenza revisited. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 4):D59–66.

Nakajima N, Sato Y, Katano H, et al. Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings of 20 autopsy cases with 2009 H1N1 virus infection. Mod Pathology: Official J United States Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2012;25:1–13.

Yamazaki Y, Hirai K, Honda T. Pseudomembranous tracheobronchitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:211–3.

Takahashi S, Nakamura M. Necrotizing tracheobronchitis caused by influenza and Staphylococcus aureus co-infection. Infection. 2018;46:737–9.

Rice TW, Rubinson L, Uyeki TM, et al. Critical illness from 2009 pandemic influenza a virus and bacterial coinfection in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1487–98.

Hatanaka D, Nakamura T, Kusakari M, et al. A case of necrotizing tracheobronchitis successfully treated with immunoglobulin. Pediatr Int. 2021;63:1538–40.

Robinson KM, Kolls JK, Alcorn JF. The immunology of influenza virus-associated bacterial pneumonia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;34:59–67.

Small CL, Shaler CR, McCormick S, et al. Influenza infection leads to increased susceptibility to subsequent bacterial superinfection by impairing NK cell responses in the lung. J Immunol. 2010;184:2048–56.

Funding

This research is supported by the Chongqing Medical Scientific Research Project (Joint Project of Chongqing Health Commission and Science and Technology Bureau), No. 2020FYYX163.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW and WS: drafted the main manuscript text. SW, JY and YT: treated the patient in ward. SW and WS prepared the figures and the table. YT: critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and clinical images were obtained from the patient. A copy of the written consent will be available for reviewing by the Editor-in-Chief when needed.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Yang, J., Sun, W. et al. Severe necrotizing tracheobronchitis caused by influenza B and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus co-infection in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 23, 55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00715-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00715-1