Abstract

Background

Pretomanid is a key component of new regimens for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) which are being rolled out globally. However, there is limited information on the prevalence of pre-existing resistance to the drug.

Methods

To investigate pretomanid resistance rates in China and its underlying genetic basis, as well as to generate additional minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) data for epidemiological cutoff (ECOFF)/breakpoint setting, we performed MIC determinations in the Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube™ (MGIT) system, followed by WGS analysis, on 475 Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) isolated from Chinese TB patients between 2013 and 2020.

Results

We observed a pretomanid MIC distribution with a 99% ECOFF equal to 0.5 mg/L. Of the 15 isolates with MIC values > 0.5 mg/L, one (MIC = 1 mg/L) was identified as MTB lineage 1 (L1), a genotype previously reported to be intrinsically less susceptible to pretomanid, two were borderline resistant (MIC = 2–4 mg/L) and the remaining 12 isolates were highly resistant (MIC ≥ 16 mg/L) to the drug. Five resistant isolates did not harbor mutations in the known pretomanid resistant genes.

Conclusions

Our results further support a breakpoint of 0.5 mg/L for a non-L1 MTB population, which is characteristic of China. Further, our data point to an unexpected high (14/475, 3%) pre-existing pretomanid resistance rate in the country, as well as to the existence of yet-to-be-discovered pretomanid resistance genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) remains a threat to public health. In 2021, approximately 450,000 new cases of rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB)/ multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB; defined as RR-TB with additional resistance to isoniazid) were reported worldwide [1]. Historically, RR/MDR-TB has been more difficult and costly to treat, necessitating more toxic and less effective drugs administered for a longer period of time, as compared to drug-susceptible TB (DS-TB) [2]. The recent introduction of novel drugs – the diarylquinoline bedaquiline (B) and the nitroimidazoles delamanid and pretomanid (Pa) – alongside the repurposing of the oxazolidinone linezolid (L), promise to revolutionize RR/MDR-TB therapy. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the BPaL and BPaLM (BPaL plus moxifloxacin) regimens for the treatment of RR/MDR-TB, based on data from clinical trials [3].

However, the worldwide rollout of BPaL/BPaLM regimens has been carried out despite limited information on the prevalence of resistance to these drugs, particularly the nitroimidazoles, which is mainly the result of not having rapid molecular tests. Pretomanid and delamanid are pro-drugs that share the same activation pathway, the products of ddn, fgd1, fbiA-D [4]. Loss-of-function and certain other mutations in any of these 6 genes have been associated with high delamanid/pretomanid resistance in M. tuberculosis (MTB) – in most cases, we see delamanid/pretomanid cross-resistance, but exceptions exist [5, 6]. In addition, other mechanisms must be involved in delamanid/pretomanid resistance, as strains exhibiting high minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to the drugs but no polymorphisms in these (canonical) genes have been identified [7, 8]. Because of their complex genetics, it will be difficult to develop rapid molecular tests for nitroimidazoles and, for the foreseeable future, we will most likely continue to rely on phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (pDST). pDST methods for both drugs have been described [9, 10], but a breakpoint (critical concentration) has been established only for delamanid [11, 12]. The definition of a breakpoint for pretomanid has been complicated by the discovery that one of the common MTB genotypes, lineage 1 (L1), is intrinsically less susceptible to the drug and shows a higher epidemiological cutoff (ECOFF), as compared to other lineages [10], but still lower than MICs of mutants in the canonical delamanid/pretomanid resistance genes. For the MTB L1 ECOFF to be assigned as the clinical breakpoint for all MTB lineages, it is necessary to consider treatment outcomes of patients harboring MTB L1 and treated with pretomanid-containing regimens. This type of data is still lacking.

In China, a country with high DR-TB burden, three previous studies have tested MTB clinical isolates against delamanid and/or pretomanid. Two of these studies employed the microplate Alamar Blue assay (MABA), which is not a WHO-recommended pDST method, did not present QC/reproducibility data or MTB lineage information [7, 13]. In the study by Zhang and collaborators, out of 72 MTB isolates tested, none exhibited high MICs for pretomanid; whereas in the study by Wen and coworkers, out of 220 MTB isolates analyzed, 7 (3%) and 3 (1%) were markedly resistance to delamanid and pretomanid, respectively. We used the well-established CRyPTIC UKMYC6 broth microdilution (BMD) plate for pDST [10, 12], followed by whole genome sequence (WGS) analysis [14], to test 1603 clinical MTB isolates selected from the Chinese 2015 National Drug Resistance Surveillance Collection. We reported resistance rates near 0.7%, 0.4% and 0.4% to delamanid, bedaquiline or linezolid, respectively [15]. Here, we performed pretomanid MIC determinations in the Becton and Dickinson Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube™ (MGIT) system [10], followed by WGS analysis, in 475 MTB isolated from Chinese TB patients between 2013 and 2020. The aims of this work were to further investigate the prevalence of pre-existing pretomanid resistance and its underlying genetic basis, as well as to generate additional MIC data for ECOFF/breakpoint setting in the MGIT system.

Materials and methods

MTB isolate Collection

MTB isolates were obtained from delamanid- and pretomanid-naïve TB patients from 21 provinces, 2 municipalities and 2 autonomous regions, corresponding to all 6 regions included in the Chinese Drug Resistance Surveillance Program running between 2013 and 2020 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table). 15 isolates had been previously included in an analysis of the prevalence of delamanid resistance [15]. All isolates were stored frozen on 20% glycerol and sub-cultured on Löwenstein-Jensen medium prior to further analyses at the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory (NTRL).

Broth microdilution DST

Phenotypic DST for a panel of 12 anti-TB drugs (amikacin, cycloserine, ethambutol, ethionamide, isoniazid [INH], kanamycin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, para-aminosalicylic acid, rifabutin, rifampicin [RIF] and streptomycin) was performed using the BMD method and a commercial dry plate, as previous described [10]. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration without obvious visible bacterial growth compared with positive controls.

MTB H37Rv (ATCC 27,294) strain was used to quality control (QC) all tests. The breakpoints for all 12 drugs were as described previously [12]. MDR isolates were defined as MTB resistant to at least INH and RIF, and pre-XDR were RR/MDR isolates with additional resistance to fluoroquinolones [16].

Pretomanid MIC in the MGIT

The pretomanid MIC determinations were performed as described previously [10]. The concentrations used for MIC testing were 2-fold serial dilution from 0.03 mg/L to 2 mg/L. If the MIC fell outside of this range, the test was repeated at higher (2–16 mg/L) or lower (0.004–0.016 mg/L) concentrations to avoid truncating the phenotypically wild-type MIC distribution. H37Rv was included as reference in each batch of MIC testing. This generated 19 data points, which all fell within a 4-dilution range (0.06–0.5 mg/L; Supplemental Fig. 1). This QC range is identical to the one reported by Bateson and collaborators [10]. The ECOFF for pretomanid was determined using the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) software ECOFFinder (https://www.eucast.org/mic_and_zone_distributions_and_ecoffs).

WGS Analysis

Genomic DNA was prepared using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method, then subjected to WGS using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform as described previously [17, 18]. All raw WGS data were processed with the Clockwork pipeline, originally developed for the CRyPTIC Consortium by the European Bioinformatics Institute [19]. Minimum coverage was 10 X. Sequences containing genes of the proline–glutamic acid (PE)/proline–proline–glutamic acid (PPE) family and other repetitive sequences were excluded from the analysis. Sequencing reads corresponding to ddn, fbiA-D and fgd1 were aligned to those from the H37Rv reference genome (GenBank ID: NC_000962.3). Site statistics were generated using SAMtools mpileup and gene annotation generated using snpEff software. Phylogenetic tree was visualized and modified with iTOL (v 6.4.3).

Results

Characterization of the MTB isolate Collection

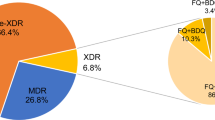

A total of 475 MTB isolates were randomly selected from the NTRL collection, including 171 (36%) isolates susceptible to all 12 drugs tested (pan-susceptible), 95 (20%) INH resistant (HR), 23 (5%) RR, 114 (24%) MDR and 48 (10%) pre-XDR isolates. The remaining 24 (5%) isolates were susceptible to INH and RIF, but resistant to at least one other drug included in the BMD plate (Supplementary Table). All the major MTB complex lineages were represented; from most abundant to least, lineage 2 (L2) (78.7%, 374/475), L4 (17.1%, 81/475), L3 (3.6%, 17/475) and L1 (0.4%, 2/475). In addition, one Mycobacterium bovis isolate was identified (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table).

Pretomanid MIC distribution in the MTB isolates

Testing of the 475 isolates for pretomanid revealed a MIC distribution with a mode equal to 0.25 mg/L and 99% statistical ECOFF equal to 0.5 mg/L (Fig. 3). Of the 15 isolates with MIC values > 0.5 mg/L, one had MIC = 1 mg/L and was identified as MTB L1 and 12 (2.5%) isolates had high MICs (≥ 16 mg/L) and can be considered resistant. The two (0.4%) remaining isolates, NTRL00030 and NTRL00212 had MICs equal to 2 mg/L and 4 mg/L, respectively, and were called “borderline” resistant. Both isolates belong to the L2 clade. There was no obvious correlation between pretomanid MIC levels and susceptibility to the 12 other anti-TB drugs tested (Table 1; Supplemental Table).

Delamanid susceptibility data was available for 9 of the pretomanid-resistant isolates (Table 1). All, except for NTRL00030 and NTRL00032, had been shown to be also resistant to delamanid.

Genomic analyses

Among the 460 pretomanid-susceptible (MIC ≤ 1 mg/L) isolates, we found 21 different synonymous and 35 nonsynonymous substitutions, affecting the 6 canonical pretomanid resistance genes, ddn, fbiA-D and fgd1. These polymorphisms were harbored by 412 (89.6%) and 48 (10.4%) isolates, respectively (Supplementary Table). Out of the 14 isolates borderline-resistant/resistant to pretomanid, only 9 isolates had non-synonymous or indel mutations in at least one of those genes, more specifically, ddn, fbiA, fbiC and fbiD. Three isolates showed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) upstream the coding region of fbiA, but they were positioned far from the putative start codon, thus unlikely to affect fbiA expression (Table 1).

Of note, NTRL00025 and NTRL00034 harbored the same 21 base-pair deletion in ddn and were both isolated from patients in Xinjiang Province. However, they were separated by 18 SNPs, including a fabG1 -15 C > T mutation conferring resistance to INH in NTRL00034; this genetic distance is greater than what has been seen in epidemiologically linked TB cases [20].

Discussion

A widely accessible test for pretomanid resistance is urgently needed to determine pre-existing resistance rates in countries where the BPaL/BPaLM regimens are to be implemented, monitor resistance trends following implementation and, more importantly, for proper management of TB patients who are candidates to begin receiving these regimens, or who fail or relapse treatment with BPaL/BPaLM. Because of the complex genetics of pretomanid (and delamanid) resistance, rapid molecular tests will require considerable effort and time to develop. We are currently limited to pDST methods, which take weeks to produce a result and demand complex laboratory infrastructure but, at least some, are robust and accessible worldwide. pDST based on the MGIT system is currently the only commercial method that has been fully validated for pretomanid testing [10]; it is already in use for MIC testing in several countries [23]. However, a breakpoint (critical concentration) has yet to be recommended by WHO, although a screen value of ≤ 2 mg/L has been published by EUCAST [24].

Our study with 475 Chinese MTB clinical isolates provided additional pretomanid MGIT MIC data to be used for breakpoint setting. Basically, we confirmed the QC range (0.06–0.5 mg/L; Supplemental Fig.) for the test, as well as the ECOFF for MTB lineages other than L1 (0.5 mg/L; Fig. 3) first reported by Bateson and collaborators [10]. MTB L1 are not well represented in the Chinese population [25] and, indeed, only one isolate in our study proved to be MTB L1 (with an MIC = 1 mg/L; Supplemental Table). In addition to this isolate, 14 others had MIC > 0.5 mg/L (Table). These included NTRL00030 and NTRL00212, MTB L2 isolates with “borderline resistance” (MIC values of 2 and 4 mg/L, respectively). NTRL00030 had been found susceptible to delamanid previously and, here, was shown to carry wild-type canonical delamanid/pretomanid resistant genes (Table). We hypothesize that the slightly higher pretomanid MIC result in this isolate is simply the result of technical variation and may have no clinical impact. On the other hand, NTRL00212 was found to harbor a mutation in the fbiD gene, which may explain the borderline resistance phenotype; to our knowledge, this mutation has never been described (Table). All the remaining 12 isolates were resistant to the highest pretomanid concentration typically tested (16 mg/L). Interestingly, only 8 of these harbored a mutation in the canonical delamanid/pretomanid resistant genes. Also of note, NTRL00032 had been tested delamanid susceptible in our previous study [15]. These observations add to data formally published [7, 8], strongly suggesting the existence of other, still unidentified delamanid/pretomanid resistance genes and mutations leading to resistance to one but not the other nitroimidazole.

The prevalence of pretomanid resistance seen in this study, near 3%, is similar to the delamanid resistance rate we reported previously [15], but greater than rates reported elsewhere [26, 27]. This highlights the importance of ensuring that delamanid/pretomanid resistance is carefully monitored in China.

We also acknowledge some limitations in this study. First, the 475-isolate collection studied here does not provide a full picture of MTB circulating in China; some provinces/municipalities contributed few, if any, isolates; and there was only one MTB L1. Parenthetically, the determination of a critical concentration for pretomanid that includes MTB L1 will require clinical outcome data from cohorts of patients infected with this MTB genotype and treated with BPaL/BPaLM. Second, the novel mutations in pretomanid resistance genes identified here, except for the loss-of-function ddn_p.Tyr29STOP, must have their association to resistance confirmed by further experimental evidence, including larger WGS/pDST association studies, protein modeling and, ideally, allelic exchange experiments.

Conclusions

Our study with 475 MTB isolates suggests that the rate of pre-existing resistance to pretomanid in China, 3%, is higher than expected, and that unknown genetic mechanisms may contribute to this. Follow-up studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further substantiate these findings.

Data availability

The datasets in the present study are accessible from the corresponding author, ZHAO YL.

Abbreviations

- ECOFF:

-

Epidemiological cutoff

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MGIT:

-

Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube™

- DR-TB:

-

Drug-resistant tuberculosis

- RR-TB/MDR-TB:

-

Rifampicin-resistant TB/ multidrug-resistant TB

- DS-TB:

-

Drug-susceptible TB

- B:

-

Bedaquiline

- Pa:

-

Pretomanid

- L:

-

Linezolid

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MTB:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- pDST:

-

Phenotypic drug susceptibility testing

- L:

-

Lineage

- MABA:

-

Microplate Alamar Blue assay

- BMD:

-

Broth microdilution

- WGS:

-

Whole genome sequence

- NTRL:

-

National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- RIF:

-

Rifampicin

- QC:

-

Quality control

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- PE/PPE:

-

Proline–glutamic acid/proline–proline–glutamic acid

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

Lange C, Dheda K, Chesov D, Mandalakas AM, Udwadia Z, Horsburgh CR. Management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):953–66.

WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Rifat D, Li SY, Ioerger T, Shah K, Lanoix JP, Lee J, Bashiri G, Sacchettini J, Nuermberger E. Mutations in fbiD (Rv2983) as a novel determinant of resistance to Pretomanid and Delamanid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 2021;65(1).

Kadura S, King N, Nakhoul M, Zhu HY, Theron G, Koser CU, Farhat M. Systematic review of mutations associated with resistance to the new and repurposed Mycobacterium tuberculosis drugs bedaquiline, clofazimine, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2020;75(8):2031–43.

Lee BM, Harold LK, Almeida DV, Afriat-Jurnou L, Aung HL, Forde BM, Hards K, Pidot SJ, Ahmed FH, Mohamed AE, et al. Predicting Nitroimidazole antibiotic resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis with protein engineering. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(2):e1008287.

Wen SA, Jing W, Zhang TT, Zong ZJ, Xue Y, Shang YY, Wang F, Huang HR, Chu NH, Pang Y. Comparison of in vitro activity of the nitroimidazoles delamanid and pretomanid against multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 2019;38(7):1293–6.

Timm J, Bateson A, Solanki P, Paleckyte A, Witney AA, Rofael SAD et al. Baseline and acquired resistance to bedaquiline, linezolid and pretomanid, and impact on treatment outcomes in four tuberculosis clinical trials containing pretomanid. PLoS Global Public Health (in press).

Schena E, Nedialkova L, Borroni E, Battaglia S, Cabibbe AM, Niemann S, Utpatel C, Merker M, Trovato A, Hofmann-Thiel S, et al. Delamanid susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using the resazurin microtitre assay and the BACTEC (TM) MGIT (TM) 960 system. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2016;71(6):1532–9.

Bateson A, Canseco JO, McHugh TD, Witney AA, Feuerriegel S, Merker M, Kohl TA, Utpatel C, Niemann S, Andres S, et al. Ancient and recent differences in the intrinsic susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex to pretomanid. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2022;77(6):1685–93.

World Health Organization. Technical Report on critical concentrations for drug susceptibility testing of medicines used in the treatment of drug resistant tuberculosis Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018.

Fowler PW, Barilar I, Battaglia S, Borroni E, Brandao AP, Brankin A, Cabibbe AM, Carter J, Cirillo DM, Claxton P et al. Epidemiological cut-off values for a 96-well broth microdilution plate for high-throughput research antibiotic susceptibility testing of M. Tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(4).

Zhang FZ, Li SS, Wen SA, Zhang TT, Shang YY, Huo FM, Xue Y, Li L, Pang Y. Comparison of in vitro susceptibility of Mycobacteria against PA-824 to identify key residues of Ddn, the Deazoflavin-Dependent Nitroreductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:815–22.

Coll F, Preston M, Guerra-Assuncao JA, Hill-Cawthorn G, Harris D, Perdigao J, Viveiros M, Portugal I, Drobniewski F, Gagneux S, et al. PolyTB: a genomic variation map for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2014;94(3):46–54.

He WC, Liu CF, Liu DX, Ma AJ, Song YM, He P, Bao JJ, Li YC, Zhao B, Fan JL, et al. Prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to bedaquiline and delamanid in China. J Glob Antimicrob Re. 2021;26:241–8.

World Health Organization. Meeting report of the WHO expert conslutation on the definition of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis, 27–29 October 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Liu DX, Huang F, Zhang GL, He WC, Ou XC, He P, Zhao B, Zhu BL, Liu F, Li ZY et al. Whole-genome sequencing for surveillance of tuberculosis drug resistance and determination of resistance level in China. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2022;28(5).

He WC, Tan YH, Liu CF, Wang YT, He P, Song ZX, Liu DX, Zheng HW, Ma AJ, Zhao B et al. Drug-resistant characteristics, genetic diversity, and Transmission Dynamics ofrifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Hunan, China, revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1).

Rodrigues C, Moore D, Crook DW, Cirillo DM, Fowler PW, Iqbal Z, Ismail NA, Mistry N, Niemann S, Peto TEA et al. Genome-wide association studies of global Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to 13 antimicrobials in 10,228 genomes identify new resistance mechanisms. Plos Biol. 2022;20(8).

Diel R, Kohl TA, Maurer FP, Merker M, Walter KM, Hannemann J, Nienhaus A, Supply P, Niemann S. Accuracy of whole-genome sequencing to determine recent tuberculosis transmission: an 11-year population-based study in Hamburg, Germany. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(5).

Manjunatha UH, Boshoff H, Dowd CS, Zhang L, Albert TJ, Norton JE, Daniels L, Dick T, Pang SS, Barry CE. Identification of a nitroimidazo-oxazine-specific protein involved in PA-824 resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:431–6.

Gomez-Gonzalez PJ, Perdigao J, Gomes P, Puyen ZM, Santos-Lazaro D, Napier G, Hibberd ML, Viveiros M, Portugal I, Campino S, et al. Genetic diversity of candidate loci linked to Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to bedaquiline, delamanid and pretomanid. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19431.

Bhalla M, Sahalchyk E, Omar SV, Aubry Nguyen H, Timm J et al. Pretomanid Resistance Surveillance Program 2020 to 2025 – An interim report. Union World Conference on Lung Health. 2023.

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 13.0, 2023.

Liu QY, Ma AJ, Wei LH, Pang Y, Wu BB, Luo T, Zhou Y, Zheng HX, Jiang Q, Gan MY, et al. China’s tuberculosis epidemic stems from historical expansion of four strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2(12):1982–92.

Liu Y, Matsumoto M, Ishida H, Ohguro K, Yoshitake M, Gupta R, Geiter L, Hafkin J. Delamanid: from discovery to its use for pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Tuberculosis. 2018;111:20–30.

Puyén ZM, Santos-Lázaro D, Vigo AN, Coronel J, Alarcón MJ, Cotrina VV, Moore DAJ. Evaluation of the broth microdilution plate methodology for susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Peru. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):705.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2305204), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7224328), Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (22JR5RA712) and Science and Technology Plan Project of Gansu Province (21JR11RA184).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H. and Y.Z. contributed in study design. B.Z., R.X., F.L., Q.L., Y.L. and F.J. conducted laboratory testing. Z.S., S.P., L.M., Y.G. and C.T. conducted data collection, and analysis. H.Z., L.H., N.W., A.G., and S.J. conducted in manuscript writing. J.T. and X.O. revised the manuscript. All the authors have read the manuscript and have approved it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of China CDC (202223). Patient consent was waived due to all isolates used in this study were from previous drug-resistance surveillance (DRS) work, and no additional data and specimens were collected. Each patient signed an informed consent form during the routine DRS.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, B., Zheng, H., Timm, J. et al. Prevalence and genetic basis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to pretomanid in China. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 23, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00697-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00697-0