Abstract

Background

The prevalence of age-related neurodegenerative diseases has risen in conjunction with an increase in life expectancy. Although there is emerging evidence that air pollution might accelerate or worsen dementia progression, studies on Asian regions remains limited. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between long-term exposure to PM10 and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in the elderly population in South Korea.

Methods

The baseline population was 1.4 million people aged 65 years and above who participated in at least one national health checkup program from the National Health Insurance Service between 2008 and 2009. A nationwide retrospective cohort study was designed, and patients were followed from the date of cohort entry (January 1, 2008) to the date of dementia occurrence, death, moving residence, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2019), whichever came first. Long-term average PM10 exposure variable was constructed from national monitoring data considering time-dependent exposure. Extended Cox proportional hazard models with time-varying exposure were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Results

A total of 1,436,361 participants were selected, of whom 167,988 were newly diagnosed with dementia (134,811 with Alzheimer’s disease and 12,215 with vascular dementia). The results show that for every 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10, the HR was 0.99 (95% CI 0.98-1.00) for Alzheimer’s disease and 1.05 (95% CI 1.02–1.08) for vascular dementia. Stratified analysis according to sex and age group showed that the risk of vascular dementia was higher in men and in those under 75 years of age.

Conclusion

The results found that long-term PM10 exposure was significantly associated with the risk of developing vascular dementia but not with Alzheimer’s disease. These findings suggest that the mechanism behind the PM10-dementia relationship could be linked to vascular damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increase in life expectancy leads to an increase in the prevalence of age-related neurodegenerative diseases [56]. Most of these diseases progress to dementia and are usually diagnosed when social and/or occupational functions cannot be performed because of acquired cognitive impairment [24]. According to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), dementia, a major neurocognitive disorder, results from severe dysfunction in one or more cognitive domains including memory, language, visuospatial ability, and social/behavioral function [15, 24]. Dementia is often divided into two broad categories: neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and non-neurodegenerative diseases such as vascular dementia [20]. According to the pathophysiological process, the clinical classification of dementia is divided into Alzheimer’s disease (50–70%), vascular dementia (20%), Lewy body dementia (5%), and frontotemporal dementia (5%) [15].

In 2016, approximately 47 million people worldwide were reported to suffer from dementia; this number is expected to triple to approximately 115.4 million by 2050 [47, 56]. In particular, the prevalence of dementia in the population aged 65 years and older is estimated to double every five years [26]. The cost of health services, including caring for people with dementia, is increasing, and patients’ families are burdened by physical, emotional, and financial stress [3, 15, 24].

Currently, there is no established cure for dementia, emphasizing the importance of prevention and early intervention [56]. While aging serves as the principal risk factor for dementia, it remains non-modifiable. Thus, identifying modifiable risk factors for dementia is crucial in order to effectively prevent and manage the risk of dementia within the population. Potential modifiable risk factors include apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4, hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes, depression, cardiovascular disease, head injury, and social isolation. Some protective factors include physical activity, healthy diet, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [15, 18, 24, 38, 43]. Environmental exposure is another risk factor that can be modified, and recent epidemiological studies have suggested that air pollution may accelerate or worsen dementia [5, 51]. In a recent systematic review, long-term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with the risk of dementia [19, 46, 58] and cognitive decline [57]. Other findings provided inconsistent evidence on the effects of PM10 and air pollution such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), or ozone (O3) exposure on dementia development and cognitive function [1, 59, 60].

Studies on air pollution and dementia remain limited in Asian cities [48]. In Korea, some studies have reported the effects of air pollution on cognitive function and Parkinson’s disease [31, 44, 52], and the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of South Korea (CREDOS) study cohort reported that PM2.5 exposure was exacerbated neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with cognitive impairment [32]. There was no PM10-dementia study in Korea, and this study is the first study to investigate the relationship between PM10 and dementia. Korea is a serious aging society, and age-related neurodegenerative diseases will put an economic burden [29]. This study aimed to determine the relationship between long-term exposure to PM10 and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in an older population using the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS).

Methods

Data source

The national health insurance service (NHIS) is a public database that covers the entire population of South Korea, and the population included in the data is over 50 million [50]. The NHIS, as the single insurer, covers 100% of the Korean population and consists of national health insurance (NHI) for both employees (70.4%) and self-employed insured individuals (26.8%), as well as medical aid (MA) beneficiaries (2.8%) in 2019 [27]. The NHIS database contains demographic and medical claims data, including types of medical care facilities, dates of visits, diagnosis codes, medical costs, procedures, prescribed drug information, and examinations. In addition, this database is linked to the death records of National Statistics Korea. The diagnostic records were coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University, which waived the need for informed consent because only de-identified data were used (IRB code KUIRB-2021-0003-01).

Study design and population

This was a nationwide, retrospective cohort study. The baseline population for our study consisted of individuals aged 65 years or older who participated in the national health screening program between 2008 and 2009. Patients were followed from the date of cohort entry to the date of dementia occurrence, death, moving residence, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2019), whichever came first. We assumed that individuals with only one health record during the study period were a result of administrative record errors, as this data source is secondary data for the national health insurance. Therefore, individuals with fewer than two health records documented between 2008 and 2019 were excluded. Additionally, the following patients were excluded: (1) those who were diagnosed with dementia or had a history of dementia-related drugs between 2005 and 2007; (2) those who died before the cohort entry date; (3) those for whom there was no information on covariates; and (4) those for whom there was no air pollution information at baseline.

We created two separate cohorts for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. The Alzheimer’s disease cohort consisted of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia-free groups, and the vascular dementia cohort consisted of vascular dementia and dementia-free groups.

Outcome definition

Referring to a previous study [4], we identified an incident case of dementia up to the fifth diagnosis code. A dementia event was defined as ≥ 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient records in the neurology or psychiatry department and prescription of dementia-related medications (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine hydrobromide, and memantine). Dementia type was classified as Alzheimer’s disease (ICD-10: F00, G30), vascular dementia (ICD-10: F01), and others (ICD-10: F02-F03, F05.1, G31.1, G31.0, G31.8).

To detect incident cases of dementia, patients who developed dementia within one year of cohort entry were censored at the time of dementia onset in each subject. Moreover, several definitions were compared to validate the definition of outcome as follows: (1) restricted to primary and secondary diagnosis codes, presence of ≥ 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient diagnoses, and a prescription of dementia medication (strict definition); a case of dementia up to the fifth diagnosis code with (2) presence of ≥ 1 record of an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis, and a prescription of dementia medication; (3) presence of ≥ 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient diagnoses, or a prescription of dementia medication; and (4) presence of either a dementia diagnosis or a prescription of dementia medication.

Exposure assessment

Air Korea (www.airkorea.or.kr) was used to collect data from the region-specific sites. The data were sent to the National Ambient Air Monitoring Information System (NAMIS), and these were confirmed and finalized by the National Institute of Environmental Research. If more than 75% of the data were complete, they were considered valid.

We obtained hourly concentrations of particles < 10 μm in diameter (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O3), and carbon monoxide (CO) at each monitoring site from 2008 to 2019. The study area included 137 districts (study population per district: 1,733 − 30,939, median size of districts: 73,512,354 km2) and 186 monitoring stations across South Korea (Supplementary Table 1), each of which had at least one monitoring site. If there were more than one monitoring station in a district, the average of the measurements was taken every hour within each district.

We then calculated district-specific daily 24-hour mean concentrations for PM10, NO2, and SO2and the daytime 8-hour [09:00–17:00] concentrations for O3and CO. We selected weekly averages of O3and CO concentrations to better represent outdoor exposure. If more than 6 h (25%) of the 24-hour measurements are missing, the concentration for that date was treated as missing. Next, we averaged the daily values over 12 months (all-season) for each district and calendar year. We also treated the values for a year as missing if more than 25% of the data were missing.

To calculate the time-varying exposure, district-specific yearly mean concentrations were assigned to individuals based on their residence in each calendar year. The time-varying exposures were defined as the 1-year averages. When the study population moved away from their residence, the moving date was assumed to be July 1, the year in which they moved.

Covariates

Potential confounders were identified in the literature, including demographic variables (age, sex, body mass index (BMI)), socioeconomic factors (insurance premium), behavioral factors (smoking, drinking, physical activity), comorbidities (depression, traumatic brain injury, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)), and ecological factors (Supplementary Table 2).

Ecological factors were collected from KOSIS (the Korean Statistical Information Service) at a province or district scale. The proportion of the elderly was calculated as the ratio of the population aged 65 years and older to the total population, and the proportion of basic livelihood security was the ratio of the number of recipients of basic livelihood security. The proportion of people without a high school diploma was defined as the population without a high school diploma, divided by those aged 25–64. Education data were available for 2005; therefore, the 2008–2009 study population’s education categories were based on the 2005 data. The ratio of the elderly and education was calculated as a single value for each district, and the proportion of basic livelihood security was calculated on the provincial scale.

Statistical analysis

Extended Cox proportional hazard models were used with time-varying exposure to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for the long-term effects of PM10. As the exposure varied over the years, the dataset was prepared for analysis using the Andersen-Gill counting process. The counting process method had a yearly record for each participant, and records were generated until one of the following occurred first: dementia onset, death, moving, or ending of a cohort event. For example, one person with no events up to 2019 had 12 annual records. Furthermore, the association between the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease was estimated according to annual mean PM10 exposure.

The final models were adjusted for potential confounders, including sex, age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, insurance premium, and comorbidities, including depression, traumatic brain injury, diabetes mellitus, stroke, CCI, proportion of basic livelihood security recipients, and proportion of people with no high school diploma. All covariates were treated as fixed variables except for age. Age was assigned to time-dependent covariates. The results are reported as estimated HRs with 95% CIs per 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10. The effects of PM10 on dementia were estimated as both continuous and categorical variables, and average exposure levels were categorized into quartiles (Q1, < 42.9 µg/m3; Q2, 42.9–47.6 µg/m3; Q3, 47.7–53.3 µg/m3; Q4, ≥ 53.4 µg/m3). To test the exposure-response relationship between PM10 and dementia, we used a restricted natural cubic spline function with 4 knots.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to estimate the potential effect modifications according to sex (male and female), age (< 75 or ≥ 75 years), stroke (yes or no), depression (yes or no), brain injury (yes or no), and diabetes mellitus (yes or no). Sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the robustness of the results to the exposure time window, potential outcome misclassifications, and confounding factors. First, the annual average concentrations of PM10 were computed for the previous three and five years (3-year, and 5-year moving). Second, alternative definitions of outcomes were applied. Third, we excluded participants who died during the study period, as death could be considered as a competing risk for dementia. Fourth, regional indicators (16 province levels) as alternative ecological factor were applied. Finally, we adjusted the models for other pollutants including NO2, SO2, O3, and CO. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 for Windows and R version 4.1.0. The statistical significance level was set at p = 0.05.

Results

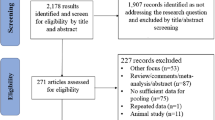

A total of 1,436,361 participants were followed after excluding 991,757 individuals by predefined exclusion criteria. A total of 167,988 participants were newly diagnosed with dementia during the study period, accounting for 11.7% of the study population. Among them, 134,811 and 12,215 individuals were identified as having Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, respectively, accounting for 80.3% and 7.3% of the total number of dementia cases, respectively (Fig. 1).

Of the 1,436,361 participants, 53.4% were female, 20.8% were aged 75 years or older, and 62.8% were overweight or obese. The majority of participants were non-smokers (75.5%), non-drinkers (78.0%), and exercised less (41.7%). Compared to all subjects, patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, particularly depression, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, and CCI. The mean follow-up time was 8.6 years and the mean concentration of PM10 was 48.4 µg/m3 (Table 1).

In the univariate model, the HR for Alzheimer’s disease with an increase in 10 µg/m3 of PM10 was 0.94 (95% CI 0.94–0.95) and that for vascular dementia was 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.06). After adjustment for demographic variables, behavioral factors, socioeconomic factors, comorbidities and ecologic variables, the HR was 0.99 (95% CI 0.98–1.00) for Alzheimer’s disease and 1.05 (95% CI 1.02–1.08) for vascular dementia for every 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10. In the case of vascular dementia, the risk of dementia increased in Q3 compared with the lowest quartile (Q1) of PM10, but it was not statistically significant in Q4 (Table 2). The exposure-response curves between PM10 and dementia showed a linear relationship up to a specific concentration but became constant at specific concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In stratification analyses by sex and age, positive and statistically significant association between PM10 and vascular dementia were observed in male and those younger than 75 years of age (HR [95% CI] per 10 µg/m3 for male:1.08 [1.03–1.12], < 75 years:1.07 [1.03–1.11]). In the subgroup with or without stroke, the HRs of vascular dementia incidence associated with PM10 exposure were 0.96 (95% CI 0.89-1.02) and 1.07 (95% CI 1.04–1.10), respectively (Table 3).

In the sensitivity analyses, the robustness of the results was confirmed by exposure time windows, outcome definitions, exclusion of subjects who died, and adjustment for the indicator variable of region. According to the co-pollutant analyses, our estimated HRs for PM10showed consistent, significant associations on vascular dementia after adjusting for 1-year moving average concentrations of other pollutants (Table 4).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between long-term exposure to PM10 and risk of dementia in Korea from 2008 to 2019. The results revealed that long-term exposure to PM10increased the risk of developing vascular dementia but was not positively associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Stratified analysis according to sex and age group showed that the risk of vascular dementia was higher in male and in those under 75 years of age. The associations were robust to various sensitivity analyses, including exposure time window and outcome definition. These findings provide evidence of a potentially significant implication of exposure to PM10 on vascular dementia.

Previous studies have suggested that long-term exposure to PM2.5significantly increases the risk of dementia [9, 19, 30, 51, 53]. Also, exposure to PM2.5was observed to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia [7, 34, 48]. In contrast to consistent evidence supporting the adverse effects of PM2.5on cognitive decline, the research on PM10has been limited and the results have not been conclusive [59]. The inconsistency in the results for PM10may be attributed to several factors, including study populations, exposure measurement methods, and statistical analysis methods. Despite the potential for heterogeneity in estimates, the effect estimate (PM10estimate per 10 µg/m3) from the prior Rome study [8] (for vascular dementia, HR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.10; for Alzheimer’s disease, HR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.91–0.99) was line with our findings (for vascular dementia, HR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.08; for Alzheimer’s disease, HR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.00).

The most common mechanisms are believed to be inflammation and oxidative stress, and PM can affect the central nervous system (CNS) through direct and indirect pathways [6, 41]. Fine particles less than 2.5 μm (PM2.5) or smaller particles can enter directly the nasal olfactory pathway, where the inhaled particles can enter systemic circulation or penetrate through cellular membranes to reach the brain [6]. Another pathway is the peripheral immune system, where PM10and PM2.5induce pro-inflammatory signals in the immune system triggering a cytokine response that transmits inflammation to the brain [6, 48]. In vivo study, long-term exposure to PM10was associated with an increased risk of amyloid-ß (Aβ) positivity with regard to CNS pathologies [33]. Another study reported that exposure to PM10and PM2.5was associated with higher concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid, a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease [2].

PM-induced systemic inflammation, especially interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), is likely to cause stroke [40], lung disease, [54], cardiovascular disease [49] and neurodegenerative diseases [13, 14, 45]. Vascular dementia is known to causes damage to brain function owing to vascular lesions, and these vascular disorders frequently occur in the brain of the elderly [55]. In addition, cardiovascular disease (CVD) associated with chronic PM exposure leads to be a pathway that can induce cerebrovascular dysregulation through vasoconstriction [35].

Stratified analysis according to sex and age group showed that the risk of vascular dementia was higher in male and in those under 75 years of age. Studies investigating gender differences in cognitive health have reported that women may be more susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease due to several factors, including longer life expectancy and higher disease morbidity [28, 42]. According to the ILSA study, men have been found to have a significantly higher risk of developing vascular dementia compared to women [16]. Another study reported that before the age of 79, vascular dementia was more prevalent among men, but after the age of 85, it became more prevalent among women [39]. The relationship between age, gender, and vascular dementia risk may be complex and influenced by risk factors, such as body size, smoking, diabetes, obesity, myocardial infarction, and stroke. For instance, some comorbidity, such as diabetes, and obesity may have a more significant negative effect on women than men, while some cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia and myocardial infarction, may be a greater influence on men [21]. Taken together, our findings suggest that the relationship between PM10exposure and vascular dementia risk may be influenced by gender and age differences, as well as other risk factors. Further research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay of these factors and their impact on cognitive health.

We conducted stratified analysis on depression, brain damage, diabetes, and stroke to determine if there was a difference in effect size based on the presence of comorbidities. In particular, we examined the difference in effect size between patients with and without stroke, which showed a significant difference. Previous studies have used effect modifiers and mediators via CVD to establish an association between air pollution and dementia [22, 25]. Although no clear effect modification was identified, our study found a potentially higher incident risk of vascular dementia related to PM10exposure among participants without stroke (HR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.03–1.11) compared to those with stroke (HR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.89–1.02). One potential explanation for this observation could be selection bias, as it is possible that patients with stroke may die before developing dementia. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to fully understand the underlying mechanisms.

To test the potential non-linear relationship between PM10and dementia, we assessed the shape of the exposure-response curve by using a restricted natural cubic spline function with 4 knots. In our curves, the slope for PM10-vascular dementia was steeper at concentrations lower than 50 µg/m3, and the slopes seed to flatter at high ranges. Some previous studies also have suggested a violation of the log-linearity assumption for particulate matter effects on population mortality and morbidity [17, 36, 37]. One possible explanation could be that populations living in areas with high exposure to PM may develop an adaptive response, resulting in smaller estimates of exposure changes per unit [37]. Also, when the PM concentration is high, there is a possibility that the actual individual’s exposure may change due to public health policy interventions such as wearing masks and reducing outdoor activities [11]. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the risk of vascular dementia may still be present even at PM10concentrations below 50 µg/m3, which is the national annual standard for PM10.

This study has some limitations. First, there is a possibility of misclassification the onset of dementia. Owing to the nature of the administrative dataset, some dementia patients might not had been diagnosed. Also, the dataset included both incident and progressive cases among people diagnosed with dementia according to ICD-10 codes. To reduce outcome misclassification, predefined criteria were defined, and the robustness of the results was tested. The dementia subtypes in this study were Alzheimer’s disease (80.3%) and vascular dementia (7.3%), which showed a distribution similar to a previous study conducted in Korea (Alzheimer’s disease:86.1% in 2016; vascular dementia:10.6% in 2016) [12].

Second, our exposure assessment was based on district-level address information at the baseline, which did not completely reflect personal exposure. Although assigning an average exposure to each individual at a fixed monitoring site would introduce a Berkson error, the error is not expected to significantly affect the measurements and estimates [23]. In addition, there was no information regarding the distance from the road. In a cohort study, living close to a major road was associated with an increased risk of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease [10].

Previous studies have mostly reported the effect of PM2.5 exposure on dementia, and PM2.5 may be a more appropriate indicator in terms of biological mechanism. Although PM2.5 exposure estimates were not available because the data were established in 2015, the correlation between PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations was high (r > 0.73) within our data (2015–2019). When other air pollutants, including NO2, SO2, O3, and CO, were added to the model, PM10 estimates were robust.

One of the strengths of this study is the first study to examine the long-term effect of PM10 on dementia, in a representative, a large population-based cohort using data from a nationwide database collected over 15 years. This provided significant statistical power to detect the association between PM10 and dementia. Second, we were able to determine the residential mobility of the study population, which could have reduced the exposure measurement error. Third, we included various covariates in the model to minimize the residual confounding. Using medical records, pre-existing diseases were identified at baseline and behavioral variables were obtained in connection with health examination data. In addition, the models were adjusted for ecological variables such as the proportion of basic livelihood security recipients and people with no high school diploma.

Conclusions

In this large population-based cohort, long-term exposure to PM10 was associated with a higher incidence of vascular dementia but not Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, the risk of vascular dementia was higher in men and those under 75 years of age. These results may contribute to understanding the relationship between air pollution and dementia by providing information on populations vulnerable to air pollution. This study may implicate the evidence that exposure to air pollution may be more associated with dementia, especially in terms of vascular damage.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study was used under license for the current study, and hence not publicly available. Data codebooks and syntaxes used for the statistical analyses are however available from the authors upon request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- EDU:

-

Proportion of people with no high school diploma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases

- NHIS:

-

National Health Insurance Service

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- PM:

-

Particulate matter

- RECIP:

-

Proportion of basic livelihood security recipients

References

Abolhasani E, Hachinski V, Ghazaleh N, Azarpazhooh MR, Mokhber N, Martin J. Air Pollution and incidence of dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Neurology. 2023;10:100. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201419.

Alemany S, Crous-Bou M, Vilor-Tejedor N, Milà-Alomà M, Suárez-Calvet M, Salvadó G, Cirach M, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Sanchez-Benavides G, Grau-Rivera O, Minguillon C, Fauria K, Kollmorgen G, Gispert JD, Gascón M, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Sunyer J, Molinuevo JL. ALFA study. Associations between air pollution and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Environ Int. 2021;157:106864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106864.

Alzheimer’s A. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013; 9:208–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003.

Baek YH, Lee H, Kim WJ, Chung J-E, Pratt N, Ellett LK, Shin J-Y. Uncertain Association between Benzodiazepine Use and the risk of dementia: a Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:201–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.017.

Bhatt DP, Puig KL, Gorr MW, Wold LE, Combs CK. A pilot study to assess effects of long-term inhalation of airborne particulate matter on early Alzheimer-like changes in the mouse brain. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127102.

Block ML, Calderon-Garciduenas L. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:506–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009.

Carey IM, Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Beevers SD, Cook DG, Strachan DP, Dajnak D, Gulliver J, Kelly FJ. Are noise and air pollution related to the incidence of dementia? A cohort study in London, England. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022404. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022404.

Cerza F, Renzi M, Gariazzo C, Davoli M, Michelozzi P, Forastiere F, Cesaroni G. Long-term exposure to air pollution and hospitalization for dementia in the Rome longitudinal study. Environ Health. 2019;18:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0511-5.

Chen H, Kwong JC, Copes R, Hystad P, van Donkelaar A, Tu K, Brook JR, Goldberg MS, Martin RV, Murray BJ, Wilton AS, Kopp A, Burnett RT. Exposure to ambient air pollution and the incidence of dementia: a population-based cohort study. Environ Int. 2017a;108:271–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.020.

Chen H, Kwong JC, Copes R, Tu K, Villeneuve PJ, van Donkelaar A, Hystad P, Martin RV, Murray BJ, Jessiman B, Wilton AS, Kopp A, Burnett RT. Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017b;389:718–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32399-6.

Chen R, Yin P, Meng X, Liu C, Wang L, Xu X, Ross JA, Tse LA, Zhao Z, Kan H, Zhou M. Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Daily Mortality. A nationwide analysis in 272 chinese cities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017c;196(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201609-1862OC.

Choi YJ, Kim S, Hwang YJ, Kim C. Prevalence of Dementia in Korea Based on Hospital Utilization Data from 2008 to 2016. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62:948–53. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2021.62.10.948.

Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R, Anstey KJ, Seaton A. Exposure to air pollution and cognitive functioning across the life course–A systematic literature review. Environ Res. 2016;147:383–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.018.

Cunningham C, Campion S, Lunnon K, Murray CL, Woods J, Deacon R, Rawlins J, Perry VH. Systemic inflammation induces acute behavioral and cognitive changes and accelerates neurodegenerative disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:304–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.024.

Cunningham EL, McGuinness B, Herron B, Passmore AP. Dement Ulster Med J. 2015;84:79–87.

Di Carlo A, Baldereschi M, Amaducci L, Lepore V, Bracco L, Maggi S, Bonaiuto S, Perissinotto E, Scarlato G, Farchi G, Inzitari D. Incidence of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia in Italy. The ILSA Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):41–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50006.x.

Forastiere L, Carugno M, Baccini M. Assessing short-term impact of PM10 on mortality using a semiparametric generalized propensity score approach. Environ Health. 2020;19:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00599-6.

Ford E, Greenslade N, Paudyal P, Bremner S, Smith HE, Banerjee S, Sadhwani S, Rooney P, Oliver S, Cassell J. Predicting dementia from primary care records: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0194735. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194735.

Fu P, Guo X, Cheung FMH, Yung KKL. The association between PM2.5 exposure and neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2019;655:1240–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.218.

Gale SA, Acar D, Daffner KR, Dementia. Am J Med. 2018;131:1161–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.022.

Gannon OJ, Robison LS, Custozzo AJ, Zuloaga KL. Sex differences in risk factors for vascular contributions to cognitive impairment & dementia. Neurochem Int. 2019;127:38–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2018.11.014.

Grande G, Ljungman PLS, Eneroth K, Bellander T, Rizzuto D. Association between Cardiovascular Disease and Long-term exposure to Air Pollution with the risk of Dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:801–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4914.

Heid IM, Kuchenhoff H, Miles J, Kreienbrock L, Wichmann HE. Two dimensions of measurement error: classical and Berkson error in residential radon exposure assessment. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;14:365–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500332.

Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30:421–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001.

Ilango SD, Chen H, Hystad P, van Donkelaar A, Kwong JC, Tu K, Martin RV, Benmarhnia T. The role of cardiovascular disease in the relationship between air pollution and incident dementia: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz154.

Jorm AF, Jolley D. The incidence of dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 1998;51:728–33. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.51.3.728.

Kim H, Song S, Noh J, Jeong I-K, Lee B-W. Data Configuration and Publication Trends for the Korean National Health Insurance and Health Insurance Review & Assessment Database. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(5):671–8. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0207.

Kim H, Noh J, Noh Y, Oh SS, Koh S-B, Kim C. Gender Difference in the Effects of Outdoor Air Pollution on Cognitive Function Among Elderly in Korea. Front. Public Health. 2019;10;7:375. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00375.eCollection 2019.

Kim YJ, Han JW, So YS, Seo JY, Kim KY, Kim KW. Prevalence and trends of dementia in Korea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:903–12. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.7.903.

Kioumourtzoglou MA, Schwartz JD, Weisskopf MG, Melly SJ, Wang Y, Dominici F, Zanobetti A. Long-term PM2.5 exposure and neurological hospital admissions in the northeastern United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:23–9. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408973.

Lee H, Myung W, Kim DK, Kim SE, Kim CT, Kim H. Short-term air pollution exposure aggravates Parkinson’s disease in a population-based cohort. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44741. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44741.

Lee H, Kang JM, Myung W, Choi J, Lee C, Na DL, Kim SY, Lee J-H, Han S-H, Choi SH, Kim SY, Cho S-J, Yeon BK, Kim DK, Lewis M, Lee E-M, Kim CT, Kim H. Exposure to ambient fine particles and neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitive disorder: a repeated measure analysis from the CREDOS (Clinical Research Center for Dementia of South Korea) study. Sci Total Environ. 2019a;10:668:411–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.447.

Lee JH, Byun MS, Yi D, Ko K, Jeon SY, Sohn BK, Lee J-Y, Lee Y, Joung H, Lee DY, KBASE Research Group. Long-term exposure to PM10 and in vivo Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78:745–56. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200694.

Lee M, Schwartz J, Wang Y, Dominici F, Zanobetti A. Long-term effect of fine particulate matter on hospitalization with dementia. Environ Pollut. 2019b;254:112926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.094.

Li C-Y, Li C-H, Martini S, Hou W-H. Association between air pollution and risk of vascular dementia: a multipollutant analysis in Taiwan. Environ Int. 2019a;133:105233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105233.

Li T, Guo Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Wang Q, Sun Z, He MZ, Shi X. Estimating mortality burden attributable to short-term PM2.5 exposure: a national observational study in China. Environ Int. 2019b;125:245–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.073.

Liu C, Chen R, Sera F, Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Guo Y, Tong S, Coelho M, Saldiva PHN, Lavigne E, Matus P, Ortega NV, Garcia SO, Pascal M, Stafoggia M, Scortichini M, Hashizume M, Honda Y, Hurtado-Díaz Ma, Cruz J, Nunes B, Teixeira JP, Kim H, Tobias A, Íñiguez C, Forsberg B, Åström C, Ragettli MS, Guo Y-L, Chen B-Y, Bell ML, Wright CY, Scovronick N, Garland RM, Milojevic A, Kyselý J, Urban A, Orru H, Indermitte E, Jaakkola JJK, Ryti NRI, Katsouyanni K, Analitis A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Chen J, Wu T, Cohen A, Gasparrini A, Kan H. Ambient Particulate Air Pollution and Daily Mortality in 652 cities. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:705–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817364.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6.

Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, Andersen K, Di Carlo A, Breteler MM, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Jagger C, Martinez-Lage J, Soininen H, Hofman A. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000;54(11 Suppl 5):4–9.

McColl BW, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Systemic infection, inflammation and acute ischemic stroke. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1049–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.019.

Mills NL, Donaldson K, Hadoke PW, Boon NA, MacNee W, Cassee FR, Sandström T, Blomberg A, Newbyet DE. Adverse cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1399.

Nebel RA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Gallagher A, Goldstein JM, Kantarci K, Mallampalli MP, Mormino EC, Scott L, Yu WH, Maki PM, Mielke MM. Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: a call to action. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(9):1171–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008.

Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X.

Park SY, Han J, Kim SH, Suk HW, Park JE, Lee DY. Impact of long-term exposure to Air Pollution on Cognitive decline in older adults without dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86:553–63. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-215120.

Perry VH, Cunningham C, Holmes C. Systemic infections and inflammation affect chronic neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:161–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2015.

Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, Booth A, Mudway I, Anstey KJ. Air Pollution and Dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70:145–S163. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180631.

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007.

Ran J, Schooling CM, Han L, Sun S, Zhao S, Zhang X, Chan K-P, Guo F, Lee RS-Y, Qiu Y, Tian L. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and dementia incidence: a cohort study in Hong Kong. Environ Pollut. 2021;271:116303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116303.

Ruckerl R, Greven S, Ljungman P, Aalto P, Antoniades C, Bellander T, Berglind N, Chrysohoou C, Forastiere F, Jacquemin B, von Klot S, Koenig W, Küchenhoff H, Lanki T, Pekkanen J, Perucci CA, Schneider A, Sunyer J, Peters A, AIRGENE Study Group. Air pollution and inflammation (interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen) in myocardial infarction survivors. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1072–80. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10021.

Seong SC, Kim Y-Y, Khang Y-H, Park J, Kang H-J, Lee H, Do C-H, Song J-S, Bang J, Ha S, Lee E-J, Shin S. Data Resource Profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):799–800. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw253.

Shi L, Wu X, Danesh Yazdi M, Braun D, Awad YA, Wei Y, Liu P, Di Q, Wang Y, Schwartz J, Dominici F, Kioumourtzoglou M-A, Zanobetti A. Long-term effects of PM2.5 on neurological disorders in the american Medicare population: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:e557–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30227-8.

Shin J, Han S-H, Choi J. Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Cognitive Impairment in Community-Dwelling older adults: the korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193767.

Smargiassi A, Sidi EAL, Robert LE, Plante C, Haddad M, Gamache P, Burnett R, Goudreau S, Liu L, Fournier M, Pelletier E, Yankoty I. Exposure to ambient air pollutants and the onset of dementia in Quebec. Can Environ Res. 2020;190:109870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109870.

Tamagawa E, van Eeden SF. Impaired lung function and risk for stroke: role of the systemic inflammation response? Chest. 2006;130:1631–3. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.6.1631.

Thal DR, Grinberg LT, Attems J. Vascular dementia: different forms of vessel disorders contribute to the development of dementia in the elderly brain. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:816–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.05.023.

Tipton PW, Graff-Radford NR. Prevention of latelife dementia: what works and what does not. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018;128:310–6. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.4263.

Thompson R, Smith RB, Karim YB, Shen C, Drummond K, Teng C, Toledano MB. Air pollution and human cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2023;10:160234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160234.

Tsai T-L, Lin Y-T, Hwang B-F, Nakayama SF, Tsai C-H, Sun X-L, Ma C, Jung C-R. Fine particulate matter is a potential determinant of Alzheimer’s disease: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2019;177:108638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.108638.

Weuve J, Bennett EE, Ranker L, Gianattasio KZ, Pedde M, Adar SD, Yanosky JD, Power MC. Exposure to Air Pollution in Relation to Risk of Dementia and related outcomes: an updated systematic review of the Epidemiological Literature. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:96001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP8716.

Zhao T, Markevych I, Romanos M, Nowak D, Heinrich J. Ambient ozone exposure and mental health: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Environ Res. 2018;165:459–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.04.015.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Health Insurance Service for offering raw data (NHIS-2021-1-323). The paper’s contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Health Insurance Service.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C1006661).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jung-Im Shim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Garam Byun: Methodology, Writing—review.

Jong-Tae Lee: Supervision, Methodology, Writing—review and editing.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval of Korea university were waived for this study due to the use of only de-identified data (IRB code KUIRB-2021-0003-01).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shim, JI., Byun, G. & Lee, JT.T. Long-term exposure to particulate matter and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in Korea: a national population-based Cohort Study. Environ Health 22, 35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-023-00986-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-023-00986-9