Abstract

Background

Recent reports have suggested that air pollution may impact thyroid function, although the evidence is still scarce and inconclusive. In this study we evaluated the association of exposure to air pollutants to thyroid function parameters in a nationwide sample representative of the adult population of Spain.

Methods

The Di@bet.es study is a national, cross-sectional, population-based survey which was conducted in 2008-2010 using a random cluster sampling of the Spanish population. The present analyses included 3859 individuals, without a previous thyroid disease diagnosis, and with negative thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO Abs) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels of 0.1-20 mIU/L. Participants were assigned air pollution concentrations for particulate matter <2.5μm (PM2.5) and Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), corresponding to the health examination year, obtained by means of modeling combined with measurements taken at air quality stations (CHIMERE chemistry-transport model). TSH, free thyroxine (FT4), free triiodothyronine (FT3) and TPO Abs concentrations were analyzed using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Modular Analytics E170 Roche).

Results

In multivariate linear regression models, there was a highly significant negative correlation between PM2.5 concentrations and both FT4 (p<0.001), and FT3 levels (p<0.001). In multivariate logistic regression, there was a significant association between PM2.5 concentrations and the odds of presenting high TSH [OR 1.24 (1.01-1.52) p=0.043], lower FT4 [OR 1.25 (1.02-1.54) p=0.032] and low FT3 levels [1.48 (1.19-1.84) p=<0.001] per each IQR increase in PM2.5 (4.86 μg/m3). There was no association between NO2 concentrations and thyroid hormone levels. No significant heterogeneity was seen in the results between groups of men, pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women.

Conclusions

Exposures to PM2.5 in the general population were associated with mild alterations in thyroid function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Air pollution is recognized as the largest environmental health risk worldwide [1,2,3]. A large proportion of the world population lives in places where the air quality standards for the protection of human health are exceeded. Spain is not an exception to this global problem. In fact during 2019, 98% and 66% of the monitoring stations in Spain recorded levels of PM2.5 and NO2 which were above the current WHO standard guidelines [4]

Air pollution exposure has been linked to a wide range of adverse health outcomes including cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, type 2 diabetes, impaired cognitive function and adverse pregnancy outcomes [1,2,3]. Oxidative stress, immune and inflammatory responses and epigenetic changes are some of the underlying factors mediating these adverse effects [5].

Increasing the knowledge about the potential emerging health effects of air pollution is essential for a better assessment of the global burden of disease attributable to these hazards [1].

Accordingly, recent reports, focused mainly on pregnancy and birth cohorts [6,7,8,9,10,11,12], but also on the general adult population [13,14,15], have suggested that air pollution may have an impact on thyroid function, although the evidence in this regard is still scarce and inconclusive. This association may however be of potential global health importance, since air pollution exposure is widespread, and thyroid hormones play essential roles in growth and development, and affect virtually every organ system, including the heart, the nervous system, the bones, the gastrointestinal system and metabolism.

Therefore, in the present study we aimed to investigate whether the exposure to air pollutants [particles with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5), and Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2)] was associated with thyroid function parameters in a nationwide sample representative of the adult population of Spain.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

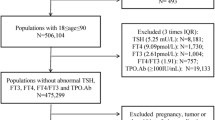

The Di@bet.es Study is a national, cross-sectional, population-based study which was conducted in 2008-2010 using a random cluster sampling of the Spanish population [16]. The study sample consisted of 5072 not pregnant adults (> 18 years), randomly selected from the National Health System registries distributed into 110 clusters (primary health care centers). Thyroid function studies [thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH], free thyroxine (FT4), free triiodothyronine (FT3) and thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO Abs)], were performed in 90% of this sample [17]. Individuals with missing data did not differ in age, sex or other characteristics of interest from individuals with complete data.

For the present analysis, we excluded all the subjects with a previous thyroid disease diagnosis, and/or taking interfering medications (levothyroxine, thionamides, amiodarone or lithium). We also excluded individuals with a positive TPO Abs test (≥ 50 IU/ml), or with very high (>20 mIU/L) or suppressed (<0.1 mIU/L) TSH levels.

This research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association [18]. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the Ethics and Clinical Investigation Committee of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (Málaga, Spain) in addition to other regional ethics and clinical investigation committees all over Spain.

Variables and procedures

The participants were invited to attend a single examination visit at their health center. Information was collected by means of an interviewer administered structured questionnaire, followed by a physical examination and blood sampling. Information on age, gender, educational level (none/basic/high school/college), and smoking habit (current, former or never been smokers) was obtained by questionnaire. Medical history and medications were also recorded. Menopause was considered in women who reported more than 12 months of amenorrhea without any other obvious pathological or physiological cause. Weight and height were measured and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated by standardized methods.

Blood samples were obtained in fasting conditions, were immediately centrifuged and the serum was frozen until analysis. A casual urinary sample was also collected and samples were frozen until analysis. Samples were managed by the biochemistry laboratory of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, the IBIMA Biobank and by the CIBERDEM Biorepository (IDIBAPS Biobank). TSH, FT4, FT3 and TPO Abs concentrations were analyzed using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Modular Analytics E170, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The functional sensitivity of the TSH assay was 0.014 mIU/L. The intra-assay coefficients of variation were: TSH, 1.5–1.2%; FT4 1.8–1.6%; FT3 1.3–2.0% and TPOAb 4.8–2.8%. The inter-assay coefficients of variation for the low and high levels of serum TSH, FT4, FT3 and TPO Abs quality control materials were 3.5 and 2.7%, 4.17 and 2.64%, 3.78 and 2.21%, and 8.5 and 5.2%, respectively. All samples were analyzed at the biochemistry laboratory of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga. Urinary iodine (UI) was analyzed using the modified method of Benotti and Benotti [19]. The intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation of UI assay were 2.01% and 4.53%, respectively. The UI assay was subjected to a program of external quality assessment for the determination of iodine in urine of the Spanish Association of Neonatal Screening (AECNE) and of Ensuring the Quality of Iodine Procedures (EQUIP) Program. All UI samples were analyzed in the Research Laboratory of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (Spain).

Exposure assessment

Modeled mean annual PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations in Spain for the period 2008 to 2010 were calculated with the CHIMERE chemistry-transport model [20]. This model calculates the concentration of gaseous species and both inorganic and organic aerosols of primary and secondary origin, including primary particulate matter, mineral dust, sulphate, nitrate, ammonium, secondary organic species and water. This model has been broadly evaluated in Spain by comparison with measured air pollutants at a large set of monitoring sites [21, 22]. The model was applied to a domain covering the Iberian Peninsula at a horizontal resolution of 0.1x0.1º. The modelled concentrations were corrected with observed values, by considering a methodology described by Martín et al [23] in which 1) a bias is calculated with regard to the observations in the Spanish air quality network of monitoring sites, 2) these biases are spatially interpolated using a krigging methodology to obtain a gridded bias, and 3) this gridded bias is applied to the modelled concentration grid. This methodology considers a different bias grid for rural and urban sites that are then combined and weighted by population density. We assigned the average annual exposure to air pollutants corresponding to the health examination year of each participant by interpolating the estimated concentrations to the centroid of their residential postal codes.

Data on mean annual temperature (°C) from each municipality of residence were obtained from the Spanish National Meteorological Agency [24]

Statistical analysis

We applied linear regression models to assess associations between air pollutant and thyroid hormone levels (TSH, FT4, FT3), which were log transformed to normalize distributions and also to limit the influence of extreme values. First, we explored any indications of non-linearity in the associations using Curve Estimation procedures. None of the models tested improved the linear model and there was no indication of a threshold effect. Association estimates were presented as percent changes with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (calculated by 100 × [exp(b)-1]), per each interquartile range (IQR) increase in air pollutant concentrations which equated to 4.86 μg/m3 PM2.5, and 12.62 μg/m3 NO2.

We also used logistic regression models to investigate the associations of ambient air pollutants with high TSH levels (defined as a percentile (p) >95), low FT4 (≤p5) and low FT3 (≤p5). These results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs again per each interquartile range (IQR) increase in air pollutants.

All these models were controlled for possible confounders such us age, sex, UI, BMI, education level, smoking status and ambient temperature. In addition, we performed subgroup analyses to test potential effect modifications in subgroups according to sex and menopausal status. Homogeneity of the ORs between subgroups was tested with the Breslow-Day test. All the statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics 23.0. Reported p values were based on two-sided tests with statistical significance set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 3859 individuals were included in the analysis (Table 1). The sample was composed of 1757 men (45.5%), 1100 premenopausal women (28.5%) and 1002 post-menopausal women (26.0%). Mean age of the population was 50.1±17.1 years (range 18–93 years). Mean and median UI concentrations were 132.2±81.6 and 114.9 μg/L respectively, concordant with an iodine sufficient population. Mean and median concentrations of TSH, FT4 and FT3 were within the expected range, taking into consideration the exclusion criteria for this analysis.

Table 2 summarizes residential estimates of outdoor air pollution concentrations assigned to the study participants in the year of examination. The median (25th-75th percentile) PM2.5 and NO2 exposure levels were 12.19 (10.50-15.36) and 16.77 (12.28-24.90) μg/m3, respectively. Most values were within the current European Ambient Air Quality Directive target values (Directive 2008/50/EC) [25].

Table 3 shows the results of the linear correlations between air pollutant concentrations and thyroid hormone levels (TSH, FT4, FT3) in crude, and multivariate adjusted linear regression models. The results showed a small, but highly significant negative correlation between PM2.5 concentrations and both FT4 and FT3 levels, which remained after multivariate adjustment of the data. In the fully adjusted model, there was a 0.5 and 0.9% reduction in FT4 and FT3 levels per each IQR increase in PM2.5 (4.86 μg/m3) . Models were run again after exclusion of potential outliers in the log-scale without any significant changes in the results. There were no associations between NO2 and thyroid hormone levels.

Table 4 shows the crude and multivariate-adjusted ORs for presenting high TSH levels (>P95), low FT4 (≤p5) and low FT3 (≤p5) per each IQR increase in air pollutant concentrations. There was a significant association between PM2.5 concentrations and the odds of presenting lower FT4 [OR 1.30 (1.08-1.57) p=0.006] and FT3 levels [OR 1.34 (1.11-1.62) p=0.002] per each IQR increase in PM2.5 (4.86 μg/m3). Again, the association remained after multivariate adjustment. There was also a reciprocal association between PM2.5 concentrations and the odds of presenting high TSH levels which reached statistical significance after multivariate adjustment [OR 1.24 (1.01-1.52) p=0.043]. As in the linear model, there was no association between NO2 concentrations and thyroid hormone levels in this model.

Figure 1 shows the results of the logistic regression analyses between PM2.5 exposures and high TSH levels (>P95), low FT4 (≤p5) and low FT3 (≤p5) in different population subgroups. Although there were some small differences between groups, no significant heterogeneity was seen in the results between the studied groups (men, pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women).

Discussion

In this nationwide sample representative of the adult population of Spain we found significant negative associations between exposures to PM2.5 and thyroid hormone levels whereas exposures to NO2 were not associated with any changes in thyroid function.

These findings are in line with previous studies suggesting that air pollution might impact thyroid function in pregnant women and neonates [6,7,8,9,10,11,12], and also in the general adult population [13,14,15]. In fact, our data almost completely coincide with those of the studies in early pregnancy by Zhao et al [6] and Ghassabian et al [8], showing significant associations between PM2.5 exposure and higher odds of maternal hypothyroxinemia. Other studies in general population samples have also shown a negative association between PM2.5 and both FT4 and FT3 levels [15] whereas in the recent study from Kim et al [14] in a national sample of Korean adults, there was an association between NO2 and CO and reduced FT4 concentration, but this association was not observed with PM10. Also, Zaccarelli-Marino et al [13] reported that the odds for hypothyroidism tended to rise when NO2, CO, and VOC concentrations increased, whereas this pattern was not observed for PM10 and SO2. It is of note that both Kim et al [14], and Zaccarelli-Marino et al [13] did not include exposures to PM2.5 in their estimations. Although PM mass is well acknowledged as an imperfect metric, PM2.5 particles differ to coarse particles in their composition, and are known to have a higher penetration capacity and reactivity. In fact, most evidence supports PM2.5 as the principal air pollutant with the greatest threat to global public health [2].

Interestingly, as suggested in other studies [8], our findings also indicate that the associations of air pollution exposure with thyroid function may occur within relatively low PM2.5 concentration ranges. In fact, the association we describe in our study occurs within exposure concentration ranges which are well below the existing European Ambient Air Quality Directive target values (PM2.5<25 µg/m3) [25]. In contrast, the WHO guidelines have recently lowered the PM2.5 recommended maximum annual exposure to 5 µg/m3 [3].

The underlying mechanisms for this association remain unclear.

Thyroid endocrine disruption could be a possibility. The thyroid hormone system is a main target of endocrine disruptor compounds at all levels [26]. Although, to the best of our knowledge, there is no conclusive evidence linking air pollutants with thyroid disruption, experimental data have demonstrated that these compounds may in fact interfere with other nuclear receptors such as oestrogen receptor signalling [27, 28]. Another potential mechanism could be related to oxidative stress (OS), and inflammatory response, secondary to the inhalation of air pollutants. In fact, OS and activation of pro-inflammatory signaling are hallmarks of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying air pollution–mediated systemic effects [5, 29]. The fact that the thyroid gland can be damaged by OS has been demonstrated in iodine excess studies [30]. Interestingly, however, the observed differences could also represent an adaptive response. Accordingly, it is well known that thyroid hormones regulate OS and increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by promoting oxidative phosphorylation [31]. IL6, among other cytokines, induces OS and has been shown to induce suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, and suppresses T3 generation by D1 and D2 deiodinases, in the setting of nonthyroidal illness [30]. In line with this, lower thyroid hormone levels could be interpreted as a compensatory mechanism to buffer ROS damage reactive to air pollutants.

Finally, due to the observational nature of the associations and the lack of toxicological studies we cannot currently explain the full spectrum of the mechanisms underlying these associations and further studies are warranted.

Our study has several strengths, including the population-based design and the inclusion of a complete thyroid function evaluation in all subjects (TSH, FT4, FT3, TPOAbs), as well as other extensive individual-level data of clinical, demographic and lifestyle variables, and iodine status, which allowed us to perform an adequate sample selection, and multivariate adjustment of the data. Also, we have analysed and expanded data to subgroups like men or post-menopausal women whereas most previous data were based on pregnant women or in the general population as a whole. Finally, our nationwide perspective, allows us to extrapolate our results more widely than local or regional studies increasing the public health implications of the findings.

The limitations of our study include its observational cross-sectional nature; therefore, as already mentioned, we cannot establish causal associations or exclude residual confounding in the relation between air pollutants and thyroid function. Also, we used ambient outdoor measurements modelled at the residential addresses of the participants as a proxy for exposure to air pollution, whereas no other relevant information such as time–activity patterns, proximity to main roads and occupational exposures was available. This is however a common limitation to most studies assessing the health effects of air pollution and, in fact, air quality guidelines focus primarily on ambient (outdoor) air pollution for their recommendations [3]. Finally, our exposure models were developed based on yearly exposures to air pollutants, whereas more refined measures to look at different lags were not available.

Conclusions

In summary, our study reports an association between the exposure to PM2.5 and markers of thyroid dysfunction in the general population which is concordant with previous studies. The nature of this association remains unknown. Additional studies are warranted to expand the data in this field. In the meantime, the association of air pollution exposure with thyroid function is of global health importance because air pollution exposure is widespread and its effect on the thyroid could have potential clinical effects on the health of the population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FT4:

-

Free thyroxine

- FT3:

-

Free triiodothyronine

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NO2 :

-

Nitrogen Dioxide

- OS:

-

Oxidative Stress

- P:

-

Percentile

- PM2.5 :

-

Particles with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 microns

- ROS:

-

Reactive Oxygen Species

- TPOAbs:

-

Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- UI:

-

Urinary iodine

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, Adeyi O, Arnold R, Basu NN, et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet. 2018;391:462–512.

Ambient air pollution: Health impacts. WHO. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/health-impacts/en/. Accessed 29 September 2021.

WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) , ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide.WHO. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228

European Environment Agency (EEA). Air quality statistics. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/dashboards/air-quality-statistics Accessed 4 May 2022

Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, Cowl CT, De Matteis S, Jung SH, Mortimer K, et al. Air Pollution and Noncommunicable Diseases: A Review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies’ Environmental Committee, Part 1: The Damaging Effects of Air Pollution. Chest. 2019;155:409–16.

Zhao Y, Cao Z, Li H, Su X, Yang Y, Liu C, et al. Air pollution exposure in association with maternal thyroid function during early pregnancy. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2019;367:188–93.

Wang X, Liu C, Zhang M, Han Y, Aase H, Villanger GD, et al. Evaluation of Maternal Exposure to PM2.5 and Its Components on Maternal and Neonatal Thyroid Function and Birth Weight: A Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2019;29:1147–57.

Ghassabian A, Pierotti L, Basterrechea M, Chatzi L, Estarlich M, Fernández-Somoano A, et al. Association of Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution with Thyroid Function During Pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912902.

Janssen BG, Saenen ND, Roels HA, Madhloum N, Gyselaers W, Lefebvre W, et al. Fetal Thyroid Function, Birth Weight, and in Utero Exposure to Fine Particle Air Pollution: A Birth Cohort Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:699–705.

Howe CG, Eckel SP, Habre R, Girguis MS, Gao L, Lurmann FW, et al. Association of Prenatal Exposure to Ambient and Traffic-Related Air Pollution with Newborn Thyroid Function: Findings from the Children’s Health Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182172.

Shang L, Huang L, Yang W, Qi C, Yang L, Xin J, et al. Maternal exposure to PM2.5 may increase the risk of congenital hypothyroidism in the offspring: a national database-based study in China. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1412.

Irizar A, Txintxurreta A, Molinuevo A, Jimeno-Romero A, Anabitarte A, Álvarez JI, et al. Association between prenatal exposure to air pollutants and newborn thyroxine (T4) levels. Environ Res. 2021;28:34621–9.

Zaccarelli-Marino MA, Alessi R, Balderi TZ, Martins MAG. Association between the Occurrence of Primary Hypothyroidism and the Exposure of the Population Near to Industrial Pollutants in São Paulo State, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3464.

Kim HJ, Kwon H, Yun JM, Cho B, Park JH. Association Between Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Thyroid Function in Korean Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:2912–20.

Zeng Y, He H, Wang X, Zhang M, An Z. Climate and air pollution exposure are associated with thyroid function parameters: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44:1515–23.

Soriguer F, Goday A, Bosch-Comas A, Bordiú E, Calle-Pascual A, Carmena R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: The Di@bet.es Study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:88–93.

Valdés S, Maldonado-Araque C, Lago-Sampedro Ana, Lillo JA, Garcia-Fuentes E, Perez-Valero V, et al. Population-Based National Prevalence of Thyroid Dysfunction in Spain and Associated Factors: Di@bet.es Study. Thyroid. 2017;2:156–66.

Association WM. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:2191–4.

Benotti J, Benotti N. Protein-bound iodine, total iodine, and butanol-extractable iodine by automation. Clin Chem. 1963;12:408–16.

Menut L, Bessagnet B, Khvorostyanov D, Beekmann M, Blond N, Colette A, CHIMERE, et al. a model for regional atmospheric composition modelling. Geosci Model Dev. 2013;2013(6):981–1028.

Vivanco MG, Palomino I, Vautard R, Bessagnet B, Martin F, Menut L, et al. Multi-year assessment of photochemical air quality simulation over Spain. Environ Model Softw. 2009;24:63–73.

Vivanco MG, Azula O, Palomino I, Martín F. Evaluating the impact of resolution on the predictions of an air quality model over Madrid area (Spain). In: Murgante B, Borruso G, Lapucci A, editors. Geocomputation, sustainability and environmental planning. Berlin: Springer; 2011. p. 145–62.

Martín F, Palomino I, Vivanco MG. Combination of measured and modelling data in air quality assessment in Spain. Int J Environ Pollut. 2012;49:36–44.

Spanish National Meteorological Agency. http://www.aemet.es Accessed 4 May 2022

Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/50/2015-09-18. Accessed 29 September 2021.

Köhrle J, Frädrich C. Thyroid hormone system disrupting chemicals. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(5):101562.

Klein GP, Hodge EM, Diamond ML, Yip A, Dann T, Stern G, et al. Gas-phase ambient air contaminants exhibit significant dioxin-like and estrogen-like activity in vitro. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:697–703.

Clemons JH, Allan LM, Marvin CH, Wu Z, McCarry BE, Bryant DW, et al. Evidence of estrogen- and TCDD-like activities in crude and fractionated extracts of PM10 air particulate material using in vitro gene expression assays. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:1853–60.

Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2054–70.

Mancini A, Di Segni C, Raimondo S, Olivieri G, Silvestrini A, Meucci E, et al. Thyroid Hormones, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6757154.

Sinha RA, Singh BK, Zhou J, Wu Y, Farah BL, Ohba K, et al. Thyroid hormone induction of mitochondrial activity is coupled to mitophagy via ROS-AMPK-ULK1 signaling. Autophagy. 2015;11:1341–57.

Acknowledgements

The di@bet.es project is a collaborative study with various phases and sub-projects in which a large number of researchers and technicians have collaborated, to whom we are indebted. Our profound appreciation goes to the primary care managers and personnel of the participating health centers, to all the fieldworkers, nurses, and technicians, and to the study participants for their altruistic participation. Samples were managed by the biochemistry laboratory of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, the IBIMA Biobank and by the CIBERDEM Biorepository (IDIBAPS Biobank), integrated in the Spanish National Biobank Network.

Funding

CIBERDEM (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad-ISCIII), Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad-ISCIII, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI17/02136, PI20/01322), Consejería de Salud y familias (PI-0144-2018), European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way to build Europe”. GRM belongs to the regional Nicolás Monardes research program of the Consejería de Salud (RC-0006-2016; Junta de Andalucía, Spain). CMA is recipient of a “Rio Hortega” research contract (CM19/00186, Instituto de Salud Carlos III). VKDG is recipient of a “Rio Hortega” research contract (CM21/00214, Instituto de Salud Carlos III).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: G.R.M, S.V. and E.G.F. Acquisition of epidemiological data: A.C.P., L.C., E.D., E.M., J.F.N., S.G., J.G., F.J.C., F.S. and G.R.M. Thyroid hormones samples management: P.O. Urinary iodine samples management: E.G.F. and C.G.R. Air Pollution modelling: M.G.V., J.L.G., M.T., V.G. and F.M.L. Creation of new software used in the work: J.L.G.G and G.A.V. Analysis and interpretation of data: G.R.M., S.V., C.M.A., N.C. and E.G.F. Drafting the article: S.V., V.K.D.G. and J.C.F.G. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Valdés, S., Doulatram-Gamgaram, V., Maldonado-Araque, C. et al. Ambient air pollution and thyroid function in Spanish adults. A nationwide population-based study (Di@bet.es study). Environ Health 21, 76 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00889-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00889-1