Abstract

Alcohol is the leading cause of healthy years lost. There is significant variation in alcohol consumption patterns and harms in Australia, with those residing in the Northern Territory (NT), particularly First Nations Australians, experiencing higher alcohol-attributable harms than other Australians. Community leadership in the planning and implementation of health, including alcohol, policy is important to health outcomes for First Nations Australians. Self-determination, a cornerstone of the structural and social determinants of health, is necessary in the development of alcohol-related policy. However, there is a paucity of published literature regarding Indigenous Peoples self-determination in alcohol policy development. This study aims to identify the extent to which First Nations Australians experience self-determination in relation to current alcohol policy in Alice Springs/Mbantua (Northern Territory, Australia).

Semi-structured qualitative yarns with First Nations Australian community members (n = 21) were undertaken. A framework of elements needed for self-determination in health and alcohol policy were applied to interview transcripts to assess the degree of self-determination in current alcohol policy in Alice Springs/Mbantua. Of the 36 elements, 33% were not mentioned in the interviews at all, 20% were mentioned as being present, and 75% were absent. This analysis identified issues of policy implementation, need for First Nations Australian leadership, and representation.

Alcohol policy for First Nations Australians in the NT is nuanced and complicated. A conscious approach is needed to recognise and implement the right to self-determination, which must be led and defined by First Nations Australians.

First Nations Australians’ experiences of current alcohol policy in Central Australia: evidence of self-determination?

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide alcohol is the leading cause of healthy years lost in people aged 15–49 years [1]. Alcohol was estimated to cost Australians at least $33 billion AUD in 2017–18 (and as high as AUD $214 billion) [2]. In the Northern Territory (NT) Australia (2015–16), it was estimated that the social cost of alcohol was $7,577.94 per adult [3]. Alcohol consumption patterns also vary greatly across populations and jurisdictions [4]. One in 12 residents (Territorians) drink every day, compared to one in 20 in the wider Australian population [5]. Furthermore, First Nations AustraliansFootnote 1 who drink, do so more often than their non-Indigenous counterparts (11 + drinks per occasion:11% versus 7%) [5, 6]. These are at levels that exceed both the single occasion and lifetime risk according to the Australian Guidelines [7].

As a result, the NT population and in particular First Nations Territorians, experience higher alcohol-attributable morbidity and mortality than other Australians [3, 8]. Alcohol-related deaths among First Nations Australians in Central Australia are more than three times the national rate (14 compared to 4.17 per 10,000; data only available from 2007) [9]. Further it this, between July 2015 and June 2017 alcohol-related hospitalisations in the NT (19.2/1000) are significantly higher than the national rate (9.1/1000) [10]. While there may be many factors that that influence this difference, including how hospitals define and record alcohol-related hospitalisations, it is not possible to identify the degree to which these factors affect the data. Nevertheless, NT residents experience alcohol-related harms at significant rates. These disparities, need to be understood within the wider context of First Nations Australians’ experiences of intergenerational trauma, colonisation, dispossession, and exclusion [11, 12].

First Nations Australians were prohibited from purchasing and consuming alcohol in the NT until the Licensing Ordinance 1964 (NT) [13]. Whilst ending such discrimination is necessary, the sudden change increased the prevalence of alcohol use and related harms. A suite of harm minimisation strategies have been developed by and with First Nations Australians to reduce harms from alcohol [14]. For example, supply reduction strategies in Alice Springs/Mbantua (the largest town in Central Australia, NT) have included: the purchase and operation of a local drinking club by Tangentyere Council; the purchase of a liquor outlet by the Central Australian Aboriginal Congress and then their intentional cancelation of the liquor licence [15]; and broad community-level restrictions on the take-away sale of alcohol [16]. These strategies have been coupled with innovative community initiatives such as night patrols and sobering-up shelters [17].

Ensuring community involvement in the planning and implementation of health policy, including in relation to alcohol, is vital to positive health outcomes for First Nations Australians [18, 19, 20]. Self-determination, an internationally recognised right for Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 2, is a cornerstone of the structural and social determinants of health. Self-determination is challenging to define and means different things to different people in varying contexts [11, 21, 22, 23]. In this paper, we define self-determination as: “… the internationally recognised and on-going right of Indigenous Peoples to collectively determine their own pathway, within and outside of existing settler societies [20].” Edwards (1980) observed that prevention cannot be imposed on a society or a community – there needs to be an invitation to change – this is still relevant today particularly for marginalised groups [24]. For Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations Australians, self-determination is a human right that is necessary in all aspect of their lives. Furthermore there is a paucity of published literature regarding Indigenous Peoples self-determination in alcohol policy development [20].

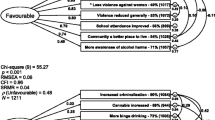

To progress the literature, we conducted a Delphi study with First Nations Australian experts to identify the elements needed for First Nations Australians’ self-determination in health and alcohol policy development [25]. The current study applies this framework (Fig. 1) to the second largest town in the Northern Territory, Alice Springs/Mbantua [25]. This study aims to identify the extent to which First Nations Australians perceive they have experienced self-determination in relation to current alcohol policy in Alice Springs/Mbantua in the Central Australian region of the Northern Territory.

A framework of elements needed for self-determination in the development of alcohol policy (adapted from [25])

Methods

First Nations Australian leadership

This study was led by AES, a Nyungar Footnote 3 woman; although based in Western Australia (WA) since 2004, she has worked, and intermittently lived in, Alice Springs/Mbantua [26]. AES has conducted a number of evaluations of alcohol and other drug interventions led by First Nations Australians in Central Australia [27, 28, 29, 30]. A priority of this work was to build and support the research capacity of the Central Arrernte peoples, who are the traditional owners for Alice Springs/Mbantua [31].

Ethical approvals

Ethical approval was provided by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2019-0729) and the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CA-19-3525). Participation was opt-in and voluntary. Both verbal and written consent was sought. Participants were offered a gift-card (supermarket gift-card value $40), in appreciation of their time [32].

Setting

As the historical and cultural context is critical to this topic, some detail will follow. The Northern Territory is Australia’s third largest and least populated mainland state/territory (1.4 million km2); comprising just 1% of the national population (229,000) [33]. Alice Springs/Mbantua is the main town for the Central Australian region (549,564 sq km) [34], and second largest outside of the capital city (Darwin). The Central Arrernte peoples refer to Alice Springs as “Mbantua” [31], and this term will be used here. Mbantua is a traditional meeting place and primary service centre for the Central Australian region. More than one-third (36%) of Central Australian residents identify as First Nations Australian and speak one or more of six prominent First Nations Australian languages [31, 33].

In addition to suburban housing, Mbantua has 18 town camps. These camps were originally on the outskirts of Mbantua and where First Nations Australians stayed while visiting the town, but have become multi-generational ‘suburbs’ with permanent housing [31]. As a result, Mbantua’s population is highly transient and likely much greater than indicated by census figures [34]. Since 1978, the NT has been self-governing; however, as a territory (rather than a state) the Australian Government can override or impose any legislation made by the NT Government. For example, the overruling of the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, 1995 (NT) [35] (voluntary assisted dying legislation) with the Euthanasia Laws Act, 1997 (Cth) [36].

Overview of NT alcohol policy

Several layers of alcohol-related legislation and by-laws are currently active in the NT (Table 1). In 2016, following years of reactionary and punitive alcohol-related legislation (e.g. Alcohol Mandatory Treatment Act, 2013 (NT)) [16, 37, 38, 39], the newly-elected Labor government initiated the Riley Review of the NT alcohol policies [40]. Following 138 written submissionsFootnote 4 and public consultations in 21 towns and communities, 220 recommendations were made by the review panel (which included one First Nations Australian woman) [40].

The NT Government supported (n = 186) or gave ‘in-principle support’ (n = 33) for the majority of recommendations. The only recommendation not supported was the cessation of Sunday take-away trading [40, 41].

As the result of the Riley Review, NT alcohol policy and legislation has been systematically reformed. Two new alcohol-related acts were implemented – the Alcohol Harm Reduction Act 2017 (NT) [42] and the Liquor Act 2019 (NT) [43]. Both pieces of legislation apply to the entire NT, including visitors. However, these reforms were also required to comply with the Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act, 2012 (Cth) [44] (Stronger Futures). Numerous reforms were made, including a minimum unit price for take-away alcohol ($1.30 per standard drink; the first Australian jurisdiction to do so) [45], re-introduction of the amended Banned Drinkers Register [46], and formalising the presence of Police Auxiliary Liquor Inspectors outside retail liquor outlets in three large regional towns – Alice Springs/Mbantua, Tennant Creek/Anyinginyi, and Katherine [39, 41].

Stronger Futures in the NT

In 2007, the Australian Government suspended the Racial Discrimination Act, 1975 (Cth) [47] in the NT to impose the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act, 2007 (Cth) [48] (‘NT Intervention’) [49, 50]. In 2012, the NT Intervention was superseded by the Stronger Futures Act in the Northern Territory 2012 (Cth) [44]. Both legislations were applicable to residents and visitors of ‘prescribed areas’ in the NT (affecting an estimated 70% of NT First Nations Australians) [50]. Prescribed areas consisted of lands under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) [51], ‘town camps’ in urban centres, and anywhere else deemed by the Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. It applied to 600,000 km2 of the NT (42%), including 500 First Nations Australian communities [50].

Criminalising possession of alcohol in prescribed areas was a key focus of the NT Intervention and Stronger Futures. However, this led to existing alcohol restrictions being overridden in more than 100 First Nations Australian communities across the NT, the majority of which were in Central Australia [37, 52, 53, 54]. Two significant amendments to alcohol policy were enforced under Stronger Futures: [i] harsher penalties for possession of alcohol in prescribed areas (fines of more than $74,000 and/or 18-months in prison), and [ii] community-developed alcohol management plans (AMPs) [40]. AMPs needed to comply with NT and Australian Government legislation and required approval from the Federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs. In 2016 these requirements were amended due to implementation difficulties. D’Abbs [55] described the barriers faced by an NT community in getting an AMP approved including changes in Government, the minister responsible, the requirements and the legislation. By late 2015 just one AMP had been approved [56]. As a result of the Parliamentary review, the Australian and NT Governments partnered to implement community-led ‘Alcohol Action Initiatives’ [37, 40]. The Initiatives are short-term partnership projects with First Nations Australian communities to implement locally led supply, harm, or demand reduction strategies [39, 57].

Alcohol policy in Mbantua

In addition to NT-wide measures, locally specific alcohol policy measures also applied in Mbantua. Since 2006, numerous local AMPs have been introduced [58], the most notable of which was the 2007 AMP that declared Mbantua to be a “dry town” under the restricted areas of the Liquor Act 1978 (NT) [59]. “Dry” areas or towns use provisions within NT legislation to prohibit the possession or consumption of alcohol within a defined area [60, 61]. In 2008, Mbantua was the first NT location to introduce scanning of identification at point-of-sale in liquor outlets [58, 62]. In 2014, starting as Temporary Beat Locations, police officers were stationed outside liquor outlets to ask people purchasing alcohol their place of residence [16, 63]; a measure now embedded in the Liquor Act 2019 (NT) [43]. Cumulatively these factors bring unique challenges for all Mbantua residents when navigating local liquor regulations [58, 62].

Participant recruitment

A multi-staged convenience sample was used to recruit First Nations Australian community members and key stakeholders. Eligibility criteria were: able to legally purchase alcohol (18 years or older); living in Central Australia; and, identifying as First Nations Australians. Participants were invited if they were: [i] community leaders who have advocated or supported community-led alcohol measures; [ii] past and current leaders and/or staff of Central Australian-based Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (including health); and [iii] community members with experience of the current alcohol policy.

To initiate the study, AES visited Mbantua in February 2020 to discuss the study scope and purpose with key community members (n = 9; seven First Nations Australians), and to identify key individuals who could be involved. Agreement was made with local Arrernte researchers and key staff of a local community-controlled organisation to conduct interviews in April 2020. However, interviews were postponed due to Covid-19 travel restrictions between Western Australia and the Northern Territory [64]. When WA’s Covid-19 restrictions eased in December 2020, AES visited Mbantua (over 3 days) to connect with possible participants, discuss the proposed interview approach, and identify appropriate timing for interviews.

Interviews were conducted in English (by AES) over 16 days in Mbantua (March 2021). Prior to arrival, invitations for interviews were emailed (by AES) to key community members and leadership of Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (n = 18), including five individuals with whom AES had existing professional relationships. While in Mbantua, three participants did not respond to follow-up phone calls, and so no further contacts were made. An additional eight participants were recommended by other participants, of whom two agreed to participate, and one brought another three participants with them for a group interview.

Interviews

Yarning

The interviews were conducted using a ‘yarning’ method [65]. Yarning is a conversational approach to interviewing that allows for the authority and foundations of the knowledge and social systems of First Nations Australians, founded on a shared understanding of relationships and accountability between all involved [65, 66]. Bessarab and Ng’andu (2010) describe three key components of yarning in a research context: (i) social yarning (to connect and establish relationship); (ii) research topic yarning (focused on experience of current alcohol policy and self-determination in Mbantua); and (iii) collaborative yarning (where solutions were discussed) [67]. The interview yarns varied depending on the experience and role of interviewees [67]. A semi-structured schedule was developed to help direct the yarn if necessary, however the conversations were participant-led [67].

Interviews were conducted in a variety of locations (e.g. public spaces, places of employment, and individuals’ homes by invitation) and when convenient for each participant (between 9:30am and 8:30pm). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by the interviewer [AES] and an Anaiwan (a First Nations Australian nation in the jurisdiction of New South Wales) research assistant. Interviews ranged in duration from 20 to 90 min (average length: 47 min). Transcripts were de-identified and pseudonyms given to all individuals and organisations mentioned.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 [68] and de-identified. The framework of self-determination in a health (and alcohol) policy context, delineated in Fig. 1, was used as the lens for analysis. This framework was developed through a Delphi study with involvement from 20 Australian experts (n = 9 First Nations Australians) [25]. Framework elements were operationalised for use in this study (by AES) – into overarching themes (n = 5), elements (n = 32), and sub-elements (n = 4). Each item of the framework was imported into NVivo12 as a node (or theme) and arranged according to a hierarchy. Three additional nodes were added under every item – to code if the interview mentioned the element, and the context of the mention (present, neutral, or absent).

Interviews were coded in three stages: [i] for evidence of an element of self-determination mentioned within current NT alcohol policy; [ii] confirmation the evidence supported the presence or absence of self-determination, or if the element was discussed as being important but not present or absent (neutral); and [iii] coding verification. A sample of de-identified coded statements (25%) were provided to co-author KSKL with 98% agreement. The one code where there was disagreement, this was discussed, and agreement reached. Once coding was verified, number of interviews (not participants) mentioning the element were collated against each element, and the percentage of interviews (not participants) mentioning the element were presented in Table 3.

Results

Participants

Twenty-one First Nations Australians aged at least 18 years and living in Central Australia participated in this study (Table 2). More than half of the participants were women (n = 12, 57%) and aged over 50 years (n = 11, 52%). Almost 40% (n = 8/21) of participants had expertise in advocacy of community-led alcohol measures, and one-third have held leadership roles in local First Nations Australian community-controlled organisations (n = 7/21). Six in ten participants were known to AES prior to the study (n = 13/21). Eleven participants were approached directly, and 10 were referred to the study by another participant. Most interviews were conducted face-to-face (n = 18/21; 86%), with the remainder conducted via phone or video conference (n = 3). Face-to-face interviews (n = 12) were comprised of one-on-one (n = 8), and group interviews (n = 4) conducted with between two and four participants (total group interview participants: n = 10).

Elements of self-determination discussed in interviews

Overall, 20 participants (n = 14 interviews) shared their experiences of current alcohol policy in Central Australia drawing on all themes from the framework of First Nations Australians’ self-determination in alcohol policy. One participant focused on their professional role in Mbantua and made no mention of the elements of self-determination contained in this framework. Table 3 shows the proportion of interviews that mentioned each element, and the related context within current alcohol policy in Central Australia (as being: present, absent, neutral). Selected quotes from interviews representing the context of each mention (present, absent, neutral) are presented in Table 4.

As shown in Table 3, 12 of the 36 elements (including 2/4 sub-elements) were not mentioned in the interviews at all. Of the elements that were mentioned, just 20% (n = 7/36) were ‘present’. In contrast, 75% of the elements were absent from current alcohol policy processes (n = 27/36). Just over a quarter (28%) of elements were seen to be important, but as no mention was made as to it being present or absent, these were coded as ‘neutral’ (n = 10/36).

Support of systemic elements needed for recognition of First Nations Australians’ self-determination

At the top level of this framework, there are six systemic (macro-level) elements needed for self-determination to occur. Five participants (all with experience in leading Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations or ACCOs Footnote 5) made 16 mentions of four of the six elements. The two elements that were not mentioned were – the need for democratic process to be embedded in the policy development system (1.4) and the need for First Nations Australians’ recognition of sovereignty through treaties (1.5). The recognition of First Nations Australian worldview (1.2), constitutional recognition (1.3), and addressing of structural determinants of health (1.6) were all mentioned by participants as needed but absent from current policy processes. Participants were mixed in relation to the importance and support of ACCOs (1.1). Interviews mentioning this element were evenly distributed and discussed the role and importance of ACCOs in providing a First Nations Australian voice to policy processes.

Values underpinning policy development processes needed for self-determination

Of the seven key values (elements) necessary for self-determination, 13 interviews (n = 19/21 participants) mentioned at least one element. Overall, these elements were mostly described as being absent from current alcohol processes. The only element present (n = 1/10) was also the one with the most mentions of it being needed (Neutral; n = 5/10; 2.3; priorities of local community to inform the process). Three elements were mentioned as absent or needed – consideration of First Nations Australians’ human rights (2.1), importance of culture (2.2) and recognition of diversity (2.4). The remaining three elements were mentioned as being absent for First Nations Australians – lives’ to be improved (2.5), to direct the process (2.6), and to have influence over policy (2.7).

Elements needed for the alcohol-related policy development process

The next level of the framework presents elements necessary for the overall policy development process. Twelve interviews (18 participants) mentioned eight elements and three sub-elements. Overall, this theme had the greatest proportion of elements which were not mentioned in the interviews (n = 6/11; 67%). Two elements were mentioned as absent from the current policy processes – First Nations Australians involvement in evaluation of policy (3.1.3) and being able to hold policymakers accountable (3.5). The remaining three elements were mentioned in the context of being both absent and needed (neutral) – the policy-making process should: involve First Nations Australians (3.1), have a feedback process (3.3) and be adjusted for the local culture (3.8). Within this theme, 85% of mentions discussed First Nations Australians as being absent from the policy development process (n = 29/34).

Decision-making elements for self-determination in alcohol policy development

The next level of the framework presents elements that focus on decision-making in alcohol policy development processes. Twelve interviews (n = 18 participants) mentioned five of these elements and one sub-element. The only element not mentioned was decision-making that has been adapted for local context (4.5). Two elements were both present and absent – decision-making involvement (4.1) and recognition of cultural obligations of First Nations Australians (4.4). Three elements were absent from the policy development process: decision-making processes led by First Nations Australians (4.1.1), participation from all parties (4.2) and involvement in evaluation with feedback (4.3).

Elements needed to implement alcohol policy

Twelve interviews (18 participants) mentioned evidence related to all six elements that were needed for implementation of alcohol policy. Just one element was absent from the current alcohol policy process – First Nations Australians’ involvement in resource allocation (5.2). Two elements were absent and needed (neutral) – implementation should be evaluated (5.1) and not discriminatory (5.3). The remaining three elements were mentioned as being both present and absent in the current context – implementation is: respectful of community priorities (5.4), results in change desired by communities (5.5), and involves First Nations Australians (5.6).

Discussion

This study qualitatively assessed the degree of self-determination experienced by First Nations Australians in alcohol policy against a framework of elements [25]. This unique framework, was derived from expert opinion in a previous study by this research team, as a broader program of work [25]. The framework was applied to participants’ yarns about their experiences of current alcohol policy in Central Australia. Critically, little evidence was found of self-determination in the participants’ experiences of current alcohol policy. A diversity of experience of self-determination was described, with 19% of elements noted as being both present and absent (n = 7/36). Implementation (Theme 5) was the most frequently referenced theme from the self-determination framework. The absence of First Nations Australian leadership and representation were notable.

Implementation of policy

Implementation was primarily discussed in the context of elements being absent from the current alcohol policy process. Participants spoke of not being consulted or having the opportunity to contribute to the development of current alcohol policies. While the recent Riley Review worked to ensure that First Nations Australians had greater opportunities to contribute to NT alcohol policy than previous policies, there is little detail of the degree to which First Nations Territorians participated in the process [40]. This likely also speaks to the uniquely layered and tangled alcohol policy context for First Nations Territorians [39, 55]. Unlike their non-Indigenous counterparts, First Nations Territorians are required to comply with the Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012 (Cth) [44], in addition to the NT-wide Alcohol Harm Reduction Act 2017 (NT) [43] and Liquor Act 2019 (NT) [43]. On face-value the alcohol restrictions in prescribed areas introduced by the Australian Government were similar to community-led ‘dry’ area rules. However, in reality, the NT Intervention replaced the carefully negotiated and locally-constructed alcohol policy measures with blanket punitive penalties [69].

First Nations Australian leadership

Fundamental to addressing alcohol-related harms is the need for First Nations Australian leadership in alcohol-related policy. However, with alcohol, this is rarely prioritised to the same degree as has been observed for other health issues [37, 70]. A consequence of this lack of leadership is that while current policies may be evidence-based, they do not recognise the specific cultural diversity and uniqueness of the NT population, nor how alcohol-related policies could be facilitating experiences of disempowerment, social exclusion, and racism which in turn have been found to have negative effects on health, including alcohol-related harm [71].

The framework applied in these data (Fig. 1) has a number of elements related to First Nations Australians being involved in or leading the development and implementation of policy (n = 12) [25]. The study participants indicated that community-based leadership in Central Australia was absent from current alcohol policy processes. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of First Nations Australian community leadership in leading policy responses to address alcohol-related harms [15, 72, 73]. For example, First Nations Australian women in Fitzroy Crossing (Western Australia) led efforts to reduce widespread alcohol-related harms [72, 74]. The collaborative process undertaken by these women enabled everyone to contribute to the process [72, 74]. As another example, over nearly a decade (1988–1997), the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council successfully advocated to reduce supply of alcohol in Curtin Springs (Northern Territory) because of significant alcohol-related harms [75]. In comparison with the Fitzroy Crossing and NPY Women’s Council examples, the absence of any First Nations Australian consultation, let alone leadership, in the NT Intervention and Stronger Futures legislation cannot be ignored [76, 77, 78].

Later amendments to Stronger Futures allowed for First Nations Australian communities in prescribed areas to develop their own AMPs [37, 39]. However, as discussed earlier in this paper, communities that did develop AMPs faced significant impediments, with just one AMP approved by late 2015 [39, 55, 56]. In 2016, AMPs were replaced with Alcohol Action Initiatives, a collaborative partnership between the Australian and NT governments and communities [39, 55, 79]. While current NT Government alcohol-related legislation allows for location-specific measures, such the dry-area rules under the Alice Springs (Mbantua) Alcohol Management Plan [58], communities in prescribed areas must also comply with the Stronger Futures legislation. Overall, this complex landscape does not allow for much space for First Nations Australians to have any leadership in alcohol-related policy.

Representation

Inclusion of First Nations Australians in the development and implementation of policy also warrants consideration of representation. All the participants who had held leadership positions within First Nations Australian community-controlled organisations (ACCOs), discussed the role of ACCOs as a representative voice. Some participants were supportive and others, while supportive, suggested that ACCOs should not be solely relied on to provide the First Nations Australian perspective. ACCOs grew from a history of communities taking leadership to ensure access to culturally secure and safe care [80]. Recently ACCOs, and their peak bodies have become the pathway for providing a “representative voice” especially in the health-sector [81]. However, the participants in this study highlighted the need to recognise the diversity of First Nations Australian perspectives and the multiple pathways taken to include an entire community [82]. Similarly, Hunt [83] and Thorpe et al., [84] describe effective engagement needed for First Nations Australians to actively participate in the policy development process, from defining the problem to evaluation of outcomes. Dreise and colleagues [82] discussed and explored the nature of First Nations Australians representation in policy, and the related consideration of how representative decision-making occurs in the layered policy development process. This supports findings from our previous studies [20, 25] which found that First Nations Australians’ self-determination, requires representation from the entire community and not just one group. The importance of policy development on a foundation of human rights, which includes self-determination, and cannot be understated [82, 84].

Implications

The framework used in this study could help assess evidence of First Nations Australians’ self-determination in alcohol and other areas of policy development. However, involvement by First Nations Australians would be required to refine and adapt this framework to suit each context. This could enable communities to take a lead role in monitoring the degree of self-determination present in local policy development processes, rather than it being defined by policymakers. While this study demonstrated an overall absence of self-determination from the context of current alcohol policy in Mbantua (Alice Springs), it does provide some evidence of areas that could be improved for greater engagement of the local First Nations Australian community (e.g., communication of outcomes and progress of current legislation). For policymakers, change is needed throughout the policy development stages – not just when implementing policy – for First Nations Australians’ right to self-determination to be recognised. While these results have identified the absence of self-determination within this context, there is also a need to explore the way that First Nations Australians’ self-determination could be recognised and part of the alcohol policy development process for First Nations Australians in Mbantua.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the interviews focused on participants’ experiences of current alcohol policy in the NT, however, the framework itself [25] was finalised after the interviews were conducted, meaning that its elements were applied to the interview yarning data retrospectively. As such, participants were not probed about specific elements of self-determination contained in this framework. Although most elements contained in this framework were mentioned in the interviews (n = 24/36), the majority of the discussion was on the absence (n = 24/36), rather than presence (n = 7/36), of framework elements. Despite this, the framework provided a useful independent comparator to gauge the degree of self-determination evident in current alcohol policy in Central Australia. Secondly, a relatively small sample was recruited (n = 21) and yarning interviews focused on the experiences of only First Nations Australian community members, not of policy makers or non-First Nations Australian community members. The participants, however, shared their vast experience and knowledge in this study (Table 2). Thirdly, AES’ existing professional relationship with many participants (n = 13/21) was a strength and a limitation. While First Nations Australian participants were willing to take part in an interview, the longstanding relationship between AES and participants could be a potential source of bias. All efforts were taken to minimise bias (e.g., the yarning method used in the interview schedule enabled participants to discuss their priorities in relation to current alcohol policy). The existing relationships also ensured that there was both cultural accountability to the local community, and a longstanding relationship founded on reciprocity [85, 86]. Finally, this study was conducted at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. It is unclear to what extent this had any influence on perceptions of self-determination.

Conclusion

Alcohol policy for First Nations Australians in the NT, is nuanced and complicated. The self-determination framework used to assess local current alcohol policy processes, while identifying some evidence of First Nations Australians’ self-determination, there were more elements absent. The importance of self-determination and how it contributes to the health and wellbeing of First Nations Australians needs consideration when developing policy. Self-determination is not something that can be simply applied. A conscious approach is needed to recognise and implement the right to self-determination, which must be led and defined by First Nations Australians. To achieve this, in relation to alcohol policy, a shift is needed in the way First Nations Australians and their health needs are considered and recognised.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to small participant numbers, protection of confidentiality, and in line with the ethical approvals from Curtin University and the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committees.

Notes

First Nations Australians has been used to collectively refer to the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. First Nations Territorians has been used to refer to those First Nations Australians residing in the Northern Territory (Australia). Where possible to the local language group has been used.

Indigenous Peoples has been used in reference to Indigenous Peoples in an international context, specifically those in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Nyungar people are First Nations Australians traditionally residing in the South-west region of Australia (Geraldton to Esperance, Western Australia) [26]. Co-author MW is also a member of the Nyungar nation. MW has a background in social work, and research focuses on culturally secure systems change framework for service providers in partnership with Nyungar elders. Other authors (KSKL, AS, SA) have heritage from outside Australian.

Submissions came from many sources including researchers and research institutes, government and Aboriginal community-controlled service providers, and alcohol retailers and suppliers [40].

ACCOs: Aboriginal (First Nations Australian) Community-Controlled Organisations are First Nations Australian community-developed and controlled service providers with First Nations Australian community elected boards of governance [87].

Abbreviations

- ACCOs:

-

Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations or ACCOs

- AES:

-

Annalee Elizabeth Stearne (Author)

- AMP:

-

Alcohol management plans

- AUD:

-

Australian dollar

- BDR:

-

Banned drinkers register

- ID:

-

Identification

- KSKL:

-

KS Kylie Lee (Co-Author)

- NHMRC:

-

National health and medical research council

- NT:

-

Northern Territory

- WA:

-

Western Australia

References

Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SRM, Tymeson HD, Venkateswaran V, Tapp AD, Forouzanfar MH, Salama JS, et al: Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31310-2

Whetton S, Tait RJ, Gilmore W, Dey T, Agramunt S, Abdul Halim S, McEntee A, Mukhtar A, Roche A, Allsop S, Chikritzhs T: Examining the Social and Economic Costs of Alcohol Use in Australia: 2017/18. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University; 2021.

Smith J, Whetton S, d’Abbs P: The Social and Economic Costs and Harms of Alcohol Consumption in the NT. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research; 2019.

Conigrave JH, Lee KSK, Zheng C, Wilson S, Perry J, Chikritzhs T, Slade T, Morley K, Room R, Callinan S, et al: Drinking risk varies within and between Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander samples: a meta-analysis to identify sources of heterogeneity. Addiction. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15015

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare: National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019 – Northern Territory Fact Sheet. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare; 2020.

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare: National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Drug Statistics series no. 32. PHE 270. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare; 2020.

Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2020.

Skov S, Chikritzhs T, Li S, Pircher S, Whetton S: How much is too much? Alcohol consumption and related harm in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 2010. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03905.x

Chikritzhs T, Pascal R, Gray D, Stearne AE, Saggers S, Jones P: Trends in Alcohol-Attributable Deaths Among Indigenous Australians 1998–2004. National Alcohol Indicators Bulletin 11. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University; 2007.

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare; 2020.

Mazel O: Indigenous health and human rights: A reflection on law and culture. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040789

Gray D, Cartwright K, Stearne AE, Saggers S, Wilkes E, Wilson M: Review of the harmful use of alcohol among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet; 2018.

Licensing Ordinance 1964, NT http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nt/num_ord/lo196435o1964203/.

Gray D, Sputore B, Stearne AE, Bourbon D, Strempel P: Indigenous Drug and Alcohol Projects: 1999–2000. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs; 2002.

Brady M: Teaching ‘Proper’ Drinking? Clubs and pubs in Indigenous Australia. Canberra: ANU Press; 2017.

d’Abbs P: Widening the gap: The gulf between policy rhetoric and implementation reality in addressing alcohol problems among Indigenous Australians. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12299

Blagg H, Valuri G: An Overview of Night Patrol Services in Australia. Canberra: Attorney-General’s Department in partnership with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission; 2003.

Gray D, Saggers S, Sputore B, Bourbon D: What works? A review of evaluated alcohol misuse interventions among Aboriginal Australians. Addiction 2000. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951113.x

Gray D, Stearne AE, Wilson M, Doyle M: Indigenous-specific Alcohol and Other Drug Interventions: Continuities, Changes, and Areas of Greatest Need. ANCD Research Paper 20. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs; 2010.

Stearne AE, Allsop S, Shakeshaft A, Symons M, Wright M: Identifying how the principles of self-determination could be applied to create effective alcohol policy for First Nations Australians: Synthesising the lessons from the development of general public policy. Int J Drug Policy. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103260

Behrendt L: Self-determination and Indigenous policy: The rights framework and practical outcomes. Journal of Indigenous Policy. 2002.

Behrendt L, Vivian A: Indigenous elf-determination and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities: A Framework for Discussion. Occassional Paper. Victoria: Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission; 2010.

Te Hiwi BP: “What is the spirit of this gathering?” Indigenous sport policy-makers and self-determination in Canada. Int Indig Policy J. 2014. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2014.5.4.6

Edwards G. Prevention and the balance of strategies. In: Drug Problems in the Socio Cultural Context: A Basis for Policies and Programme Planning. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. p. 224–32.

Stearne AE, Lee KSK, Allsop S, Shakeshaft A, Wright M: First Nations Australians’ self-determination in health and alcohol policy development: a Delphi Study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00813-6

South West Aboriginal Land Council, Host J, Owen C: “It’s Still in My Heart, This is My Country”: The Single Noongar Claim History. Perth: UWA Publishing; 2009.

Saggers S, Stearne AE: The Foundation for Young Australians Youth Led Futures. Stage 1 Jaru Pirrjirdi (Strong Voices) Project: Final Report. Perth: Centre for Social Research Edith Cowan University; 2007.

Stearne AE: Drug and Alcohol Services Association of Alice Springs Community-Based Outreach Report. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology; 2007.

Stearne AE, Wedemeyer S, Miller S, Miller G, McDonald G, White M, Ramp J: Indigenous community-based outreach program: the program and its evaluation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28:A60.

Saggers S, Stearne AE: Building ‘strong voices’ for Indigenous young people: Addressing substance misuse and mental health issues in Australia. Invited presentation. In 1st International Conference of Indigenous Mental Health: 1st National Meeting of Indigenous Mental Health. Brasilia, DF, Brazil; 2007.

Foster D, Williams R, Campbell D, Davis V, Pepperill L: ‘Researching ourselves back to life’: new ways of conducting Aboriginal alcohol research. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230600644673

National Health and Medical Research Council: Payment of participants in research: information for researchers, HRECs and other ethics review bodies. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2019.

2016 Census of Population and Housing: General Community Profile. Alice Springs (70201). Catalogue number 2001.0 [https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/70201?opendocument]

Foster D, Mitchell J, Ulrik J, Williams R: Population and mobility in the town camps of Alice Springs. A report prepared by Tangentyere Council Research Unit. Canberra: Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre; 2005.

Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995, NT https://legislation.nt.gov.au/en/Legislation/RIGHTS-OF-THE-TERMINALLY-ILL-ACT-1995.

Euthanasia Laws Act 1997, Cth https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2004A05118.

d’Abbs P: Alcohol Policy in the Northern Territory: Toward a Critique and Refocusing. Darwin: A submission to the Northern Territory Alcohol Policies and Legislation Review; 2017.

Stearne AE, Lee KSK, Allsop S, Shakeshaft A, Wright M. Self-determination by First Nations’ Australians in alcohol policy: lessons from Mbantua/Alice Springs (Northern Territory, Australia). Self-determination by First Nations’ Australians in alcohol policy: lessons from Mbantua/Alice Springs (Northern Territory, Australia). Int J Drug Policy. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103822.

Clifford S, Smith J, Livingston M, Wright C, Griffiths K, Miller P: A historical overview of legislated alcohol policy in the Northern Territory of Australia: 1979–2021. BMC Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11957-5

Riley T, Angus P, Stedman D, Matthews R: Alcohol Policies and Legislation Review. Final Report. Darwin: Northern Territory Government; 2017.

Northern Territory Government: Northern Territory Government Response to the Alcohol Policies and Legislation Review. Final Report. Darwin: Northern Territory Government; 2017.

Alcohol Harm Reduction Act 2017, NT https://legislation.nt.gov.au/Search/~/link.aspx?_id=C052FFBA4B0C408492E327095CD82ACE&_z=z

Liquor Act 2019, NT https://legislation.nt.gov.au/en/Legislation/LIQUOR-ACT-2019.

Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012, Cth https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00446.

Taylor N, Miller P, Coomber K, Livingston M, Scott D, Buykx P, Chikritzhs T: The impact of a minimum unit price on wholesale alcohol supply trends in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13055

Smith J, Livingston M, Miller P, Stevens M, Griffiths K, Judd J, Thorn M. Emerging alcohol policy innovation in the Northern Territory, Australia. Health Promot J Austr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.222.

Racial Discrimination Act 1975, Cth https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00089.

Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007, Cth https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2011C00053

Altman J, Hinkson M (Eds.): Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia. Melbourne: Arena Printing; 2007.

Parliament of Australia The Senate: Select Committee on Regional and Remote Indigenous Communities. Second Report 2009. Canberra: Senate Printing Unit Department of the Senate; 2009.

Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act 1976, Cth https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00111

Hudson S: Alcohol Restrictions in Indigenous Communities and Frontier Towns. CIS Policy Monograph 116. Sydney: Centre for Independent Studies; 2011.

Brady M: Out from the shadow of prohibition. In Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia. Edited by Altman J, Hinkson M. Melbourne: Arena Printing; 2007: 185–194

Vivian A, Schokman B: The Northern Territory Intervention and the fabrication of special measures. Aust Indig Law Rev. 2009.

d’Abbs P, Burlayn J: Aboriginal alcohol policy and practice in Australia: A case study of unintended consequences. Int J Drug Policy. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.004

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights: 2016 Review of Stronger Futures Measures Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2016.

Alcohol Action Initiatives [https://health.nt.gov.au/professionals/alcohol-and-other-drugs-health-professionals/alcohol-for-health-professionals/alcohol-management-plans/alcohol-action-initiatives]

Alice Springs Alcohol Reference Group: Alice Springs Alcohol Management Plan 2016–2018. Alice Springs: Alice Springs Alcohol Reference Group; 2016.

Liquor Act 1978, NT https://legislation.nt.gov.au/en/LegislationPortal/Acts/~/link.aspx?_id=63EF7B180554439DA50A21BA6D8A1FFF&_z=z&format=assented

National Drug Research Institute, Chikritzhs T, Gray D, Lyons Z, Saggers S: Restrictions on the Sale and Supply of Alcohol: Evidence and Outcomes. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology; 2007.

Brady M: Equality and difference: persisting historical themes in health and alcohol policies affecting Indigenous Australians. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.057455

Senior K, Chenhall R, Ivory B, Stevenson C: Moving Beyond the Restrictions: The Evaluation of the Alice Springs Alcohol Management Plan.For the Northern Territory Department of Justice, Liquor Licensing Commission. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research; 2009.

Fisher A. (2016, Feb 8). Violence rising in Darwin, as homeless drinkers relocate, NT Police Association says. ABC News (Online). https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-07/nt-police-association-claims-problem-drinkers-relocate-to-darwin/7146580?WT.ac=statenews_nt&fbclid=IwAR1b219XXKG9VO-zUW3FLs-pAA7E9BZKKGRzsCqJuI_Uu2P6sO9kxPPlkbo

Laschon E. WA’s hard border is about to end, but have its residents forgotten the cononavirus messages? ABC News (Online). 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-13/are-west-australians-ready-for-the-hard-border-to-come-down/12876056

Dean C. A yarning place in narrative histories. Hist Educ Rev. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1108/08198691201000005

Rynne J, Cassematis P: Assessing the prison experience for Australian First Peoples: A prospective research approach. Int J Crime Justice Soc Democr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v4i1.208

Bessarab D, Ng’andu B: Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int J Crit Indig. 2010. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

QSR International: NVivo 12. 12.1, / 26 June 2018 edition: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2018.

Australian Human Rights Commission: Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Bill 2011 and two related Bills. Australian Human Rights Commission: Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission; 2012.

Brady M: Indigenous Australia and Alcohol Policy: Meeting Difference with Indifference. Sydney: UNSW Press; 2004.

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, Gee G: Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Shanthosh J, Angell B, Wilson A, Latimer J, Hackett ML, Eades AM, Jan S: Generating sustainable collective action: Models of community control and governance of alcohol supply in Indigenous minority populations. Int J Drug Policy. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.09.011

Gray D, Wilkes E: Alcohol restrictions in Indigenous communities: an effective strategy if Indigenous-led. Med J Aust. 2011. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03083.x

Elliott E, Latimer J, Fitzpatrick J, Oscar J, Carter M: There’s hope in the valley. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02422.x

Factsheet: NPY Women’s Council: Advocacy Substance Abuse: Alcohol [http://www.npywc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/13-Substance-Abuse-Alcohol.pdf]

Nicholson A, Watson N, Vivian A, Longman C, Priest T, Santolo JD, Gibson P, Behrendt L, Cox E: Listening but not hearing: a response to the NTER Stronger Futures Consultations June to August 2011. Sydney: Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning Research Unit, University of Technology Sydney 2012.

Research for a better future. Keynote address at the Coalition for Research to Improve Aboriginal Health: 3rd Aboriginal Health Research Conference (5 May 2011) [https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/PDF/Pat_Anderson-CRIAH-27_04_2011.pdf]

Cowan A: UNDRIP and the Intervention: Indigenous self-determination, participation, and racial discrimination in the Northern Territory of Australia. Indigenous rights in the Pacific Rim. Pacific Rim Law Policy J. 2013.

Northern Territory Government: Northern Territory Alcohol Harm Minimisation Action Plan 2018–19. Darwin: Northern Territory Government; 2019.

Mazel O: Self-Determination and the right to health: Australian Aboriginal community controlled health services. Human Rights Law Review. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngw010

Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations (Coalition of the Peaks) [https://coalitionofpeaks.org.au/]

Dreise T, Markham F, Lovell M, Fogarty W, Wighton A: First Nations Regional and National Representation: Aligning Local Decision Making in NSW with Closing the Gap and the Proposed Indigenous Voice. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU; 2021.

Hunt J: Engaging with Indigenous Australia – exploring the conditions for effective relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. In Issues paper no 5 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Australian Government; 2013.

Thorpe A, Arabena K, Sullivan P, Silburn K, Rowley K: Engaging First Peoples: A Review of Government Engagement Methods for Developing Health Policy. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute; 2016.

National Health and Medical Research Council: Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003.

National Health and Medical Research Council: National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Research Involving Humans. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2007.

Khoury P: Beyond the biomedical paradigm: The formation and development of Indigenous community-controlled health organizations in Australia. Int J Health Serv. 2015, 45:471–494.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the time and support of the study participants, Mbantua advisors and those that have inspired this study. Further to this the support of the investigators, the students and the staff of Centre of Research Excellence in Indigenous Health and Alcohol, especially Taleah Reynolds who assisted with interview transcription. This study is part of a wider PhD study (AES), exploring how self-determination by First Nations Australians can be recognised and included in the development of alcohol policy. Two of the authors, including AES, are First Nations Australians, providing an Indigenous perspective and worldview to this research.

Funding

This study was funded and supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council for the Centre of Research Excellence in Indigenous Health and Alcohol (ID#1117198). Funding for publication was provided by Curtin University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.S, K.S.K.L.; methodology, A.E.S.; validation, A.E.S. K.S.K.L.; formal analysis, A.E.S.; investigation, A.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.S.; writing—review and editing, A.E.S., K.S.K.L., S.A., A.S., M.W.; planning and implementation supervision, K.S.K.L., S.A., A.S., M.W; project administration, A.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council and approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2019-0729) and the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CA‐19‐3525). Participation was opt-in and voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study, prior to the commencement of the interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Stearne, A.E., Lee, K.K., Allsop, S. et al. First Nations Australians’ experiences of current alcohol policy in Central Australia: evidence of self-determination?. Int J Equity Health 21, 127 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01719-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01719-z