Abstract

Background

Nut consumption is known to reduce the risk of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease. However, in previous studies, portion sizes and categories of nut consumption have varied, and few studies have assessed the association between colorectal cancer risk and nut consumption. In this study, we investigated the relationship between nut consumption and colorectal cancer risk.

Methods

A case-control study was conducted among 923 colorectal cancer patients and 1846 controls recruited from the National Cancer Center in Korea. Information on dietary intake was collected using a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 106 items, including peanuts, pine nuts, and almonds (as 1 food item). Nut consumption was categorized as none, < 1 serving per week, 1–3 servings per week, and ≥3 servings per week. A binary logistic regression model was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between nut consumption and colorectal cancer risk, and a polytomous logistic regression model was used for sub-site analyses.

Results

High nut consumption was strongly associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer among women (adjusted ORs: 0.30, 95%CI: 0.15–0.60 for the ≥3 servings per week group vs. none). A similar inverse association was observed for men (adjusted ORs: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.17–0.47). In sub-site analyses, adjusted ORs (95% CIs) comparing the ≥3 servings per week group vs none were 0.25 (0.09–0.70) for proximal colon cancer, 0.39 (0.19–0.80) for distal colon cancer, and 0.23 (0.12–0.46) for rectal cancer among men. An inverse association was also found among women for distal colon cancer (OR: 0.13, 95% CI: 0.04–0.48) and rectal cancer (OR: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.17–0.95).

Conclusions

We found a statistically significant association between high frequency of nut consumption and reduced risk of colorectal cancer. This association was observed for all sub-sites of the colon and rectum among both men and women, with the exception of proximal colon cancer for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total global consumption of nuts has increased 59% over the past decade [1]. Per capita consumption of seeds and nuts in the Korean population was 3.0 g/day in 1998, which increased to 7.6 g/day in 2015 [2]. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the labelling of food products containing nuts to indicate that nuts may reduce the risk of heart-related diseases.

Nuts contain many nutrients, including high quality vegetable protein, fat, unsaturated fatty acids, fiber, vitamins (e.g., vitamin E, vitamin B6 folate, niacin), minerals (e.g., zinc, potassium, calcium, magnesium), phytochemicals (e.g., flavonoid, carotenoids, phytosterols), and other bioactive compounds [3,4,5,6,7,8]. These nutrients may reduce the risk of overall mortality [9, 10] and incidence of colorectal and endometrial cancer [11], cardiovascular diseases [12], type 2 diabetes [13, 14], and metabolic syndrome [15]. These health effects may be due to various mechanisms, including antioxidant activity [16], reduction of DNA damage [17], regulation of inflammatory response and immunological activity [18], and anti-carcinogenic effects [19].

Few epidemiologic studies have assessed the association between nut consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Both the Nurses’ Health Study [20] and the Adventist Health Study [21] conducted in the United States suggested a null association. In the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study [22], women in the highest nut and seed intake group had a significantly decreased risk of colon cancer. The results of studies examining peanut consumption and colorectal cancer risk in Taiwan [23] have suggested an inverse association for women. Several previous case-control studies have also been implemented, but results were conflicting [24,25,26].

The type and recipe of Korean nut intake differs from that in other countries. Nuts are mainly consumed as snacks in Korea [27]. Previous studies have grouped nuts along with peanut butter and seeds [20, 22], or had only one category for peanut products and did not consider tree nuts or seeds [23]. In addition, few studies have assessed the association of nut consumption with colorectal cancer by sub-site [20, 22]. In the current study, we investigate the relationship between nut intake and colorectal cancer risk by sub-site among Korean adults.

Methods

Study population

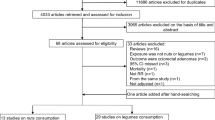

Data on newly diagnosed colorectal cancer cases were collected from August 2010 to August 2013 at the Center for Colorectal Cancer of the National Cancer Center in Korea. To minimize recall bias, colorectal cancer patients were invited to participate in the study while they were hospitalized for cancer diagnosis or surgery. Of 1427 eligible cases, 1259 were invited, and 1070 agreed to participate. A total of 168 patients were excluded for the following reasons: 1) difficulty hearing or communicating or 2) unavailable to meet in person during their hospital stay. We also excluded cases with no record of completing a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SQFFQ) (145 cases) and cases who reported energy intakes of less than 500 kcal/day or greater than 4000 kcal/day (2 cases). Controls were selected from among the Korean population who had health screenings through the National Health Insurance program at the same hospital where the cases were treated. From among the 14,201 visitors at the hospital between October 2007 and December 2014, participants with an incomplete SQFFQ (n = 5044) and 120 participants who reported inadequate or excessive intake of calories (< 500 kcal/day or ≥ 4000 kcal/day) were excluded. Cases and qualified controls (n = 9037) were matched on sex and 5-year age group (1:2 ratio). Consequently, the final analysis included 923 cases and 1846 controls. All participants were given a detailed description of the study, and written informed consent was collected from all participants. The present study guidelines were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center (IRB No. NCCNCS-10-350 and NCC 2015–0202).

Data collection

Data on general characteristics; family history of cancer; drinking, smoking, and exercise habits; and dietary intakes were collected by a trained dietitian using structured questionnaires. Dietary information was examined using an SQFFQ that was developed by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and whose reliability and validity have been demonstrated [27]. The SQFFQ was developed based on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which was conducted in 1998. Food items were selected based on the cumulative percentage contribution and cumulative multiple regression coefficients of 17 major nutrients. The SQFFQ was designed to measure typical food intake habits during the course of one year and comprised 106 food items, including peanuts, pine nuts, and almonds (as 1 food item). Data from completed SQFFQs were used to calculate daily nut and calorie intake by using the Nutritional Analysis Program for Professionals, ver. 4.0 (CAN-Pro 4.0 the Korean Nutrition Society, 2012, Seoul, Korea). The SQFFQ had 9 levels of frequency (‘none or little’, ‘once a month’, ‘2–3 times a month’, ‘1–2 times a week’, ‘3–4 times a week’, ‘5–6 times a week’, ‘once a day’, twice a day’ and ‘3 times a day’) and 3 categories for portion size (1/2 serving, 1 serving, 1–1/2 servings); 1 serving was considered to be 15 g. Average nut consumption for each type of nut was categorized as none, < 1 serving per week, 1–3 servings per week, and ≥3 servings per week. Detailed clinical information on colorectal cancer was obtained from medical records and sub-sites were classified into three categories: proximal colon (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, and splenic flexure), distal colon (descending colon, sigmoid-descending colon junction, sigmoid colon) and rectum (rectosigmoid colon, rectum) [28].

Covariates

Based on the literature, the following potential confounding variables were considered in the analyses [9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 29]: age (age < 50 years, age 50–59, and age 60 or older), education level (less than high school, high school, college or above), body mass index (BMI; < 25 kg/m2, ≥25 kg/m2), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, ex-drinker, current drinker), regular exercise (no, yes). We also considered dietary factors including intakes of fruits and vegetables, red meat, calcium, and vitamin D, as well as total energy intake (continuous). Missing data for categorical covariates were included in the multivariate logistic regression models as a dummy category.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics were compared by using Pearson’s Chi-square tests for categorical variables and general linear regression for continuous variables. Considering multi-collinearity, the final model included age; education level; alcohol consumption; BMI; regular exercise; intakes of red meat, fruits and vegetables, calcium, and vitamin D; and total energy intake by using residual methods. Binary logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between nut consumption and colorectal cancer risk. Subgroup analyses of nut consumption and colorectal cancer risk by cancer sub-site (anatomical locations) were conducted using polytomous logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were stratified by sex and performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics and demographics of colorectal cancer cases and matched controls. Among the 923 colorectal cancer cases, five cases were hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and three cases were familial adenomatous polyposis. In both sexes, colorectal cancer cases tended to have lower education levels, have lower household incomes, not be engaged in regular exercise, have higher total energy intake, be a current smoker, or have a first-degree family history of colorectal cancer compared with controls. Red meat and fruit and vegetable intakes were lower among cases compared with controls.

Table 2 describes the general characteristics of the study participants according to nut consumption. Men and women with higher frequencies of nut consumption tended to have higher levels of education, more regular exercise, higher mean fruit and vegetable intake, and higher total energy intake.

Table 3 shows ORs and 95% CIs of colorectal cancer risk according to the frequency of nut consumption. After adjustment for age, education level, alcohol consumption, BMI, regular exercise, red meat intake, fruit and vegetable intake, and total energy intake, a significant inverse relationship was observed between colorectal cancer risk and nut consumption among both men and women (OR: 0.28, 95%CI: 0.17–0.47 for ≥3serving per week vs. none, p for trend = <.001 for men; OR: 0.30, 95%CI: 0.15–0.60 for ≥3serving per week vs. none, p for trend = <.001 for women).

In sub-site analyses, among men who consumed ≥3 servings per week, a reduction in risk was observed for proximal colon cancer (OR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.09–0.70), distal colon cancer (OR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.19–0.80), and rectal cancer (OR: 0.23 95% CI: 0.12–0.46) compared to men who consumed none. Similarly, compared to women who did not consume nuts, women who consumed ≥3 servings per week showed an inverse association between nut consumption and risk of colorectal cancer overall, as well as distal colon cancer (OR: 0.13 95% CI: 0.04–0.48) and rectal cancer (OR: 0.40 95% CI: 0.17–0.95).

Discussions

Our case-control study suggests a favorable association between high frequency of nut consumption and decreased risk of colorectal cancer among both men and women. The results of sub-site analyses showed an inverse association with all sub-sites of colorectal cancer, except for proximal colon cancer for women.

Our results are consistent with some previous studies. Findings from a meta-analysis of 3 cohort studies found a 24% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer for the highest category of nut consumption [13]. A cohort study of women in Taiwan found that frequent peanut intake was associated with an approximately 58% reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer [23]. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study observed a null association between consumption of nuts and seeds and the risk of colorectal cancer among women. However, an inverse association was supported for colon cancer (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.50–0.95 for consumption of 6.2 g/day vs. ≥0 g/day) [22]. In previous case-control studies conducted in the US [26] and Korea [30], there were no statistically significant associations between consumption of nuts and other legumes and risk of colorectal cancer. In sub-site analyses, the preventive effect was observed only for cancer in the distal colon and rectum. One of two existing studies found no statistically significant results regardless of anatomical site [20], and the other study found differences according to sub-site [22]. Clinical and molecular characteristics are different according to the anatomical location of colorectal cancer [31]. The relationship of some dietary ingredients with distal colon and rectal cancer risk was stronger than with proximal colon cancer [32]. There is a general lack of studies on the relationship between nut intake and colorectal cancer, so no clear cause for these differences is known.

Despite the similarity of our results with previous literature, there were differences in the assessment of nut consumption. First, our serving size (1 serving size = 15 g) was smaller than in studies conducted in other countries (1 serving size = 28 g). Second, in our study the only types of nuts included in the SQFFQ were pine nuts, peanuts and almonds, which may be difficult to compare with studies that included seeds, legumes, peanut butter and country-specific nuts. Third, the percentage of people who have allergies to nuts varies from country to country [33]. Previous studies have shown that people born in Asia have a relatively low risk for peanut and tree nut allergies compared to those born in Western countries [34, 35].

To explain the association between nut consumption and colorectal cancer risk, several biological pathways have been proposed. Peanuts are known to be rich in isoflavones, phytosterols, resveratrol and phenolic acid [36,37,38], which may have anti-cancer effects. Phytosterols, especially beta-sitosterol, have been shown both in vivo and in vitro to help normalize hyper-proliferating cells and to inhibit colon cancer [38, 39]. Resveratrol is a natural polyphenolic antioxidant, which decreases cyclins D1 and D2 and regulates the cell cycle [40]. Almonds and pine nuts contain fiber, resveratrol, selenium, flavonoids (quercetin), polyphenols (ellagic acid), and folic acid, which may prevent cancer through antioxidants, regulation of cell differentiation and proliferation, reduction of DNA damage, regulation of inflammatory response and immunological activity [17]. Each type of nut has many nutrients and phytochemicals that may be beneficial to health, and it is likely that unknown harmony effects of nuts may be related to colorectal cancer prevention. Moreover, many studies have shown a beneficial association between high nut intake and decreased risk of obesity [41,42,43] and type 2 diabetes [44, 45], which are risk factors for colorectal cancer.

This case-control study is the first exploration of the association between nut consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in the Korean population, where nut consumption frequency and patterns may differ compared with other countries. A number of potential limitations may influence the present study. First, we did not consider the manufacturing method (raw, roasted, or boiled) or any extra content (sugar, salt, seasoning, etc.). In Korea, most nuts are consumed in a processed form or as a garnish. Different preparation methods before and after cooking, time, and temperature conditions can affect nutrient composition and content of nuts [46, 47]. Second, we could not eliminate the possibility of some residual and unmeasured confounding. Previous studies have reported that people who consume nuts were more likely to have other healthier behaviors, such as lower intakes of alcohol and sodium, lower BMI, higher physical activity levels, better dietary quality, and higher socioeconomic status [9, 10, 48,49,50,51]. Our study had similar findings in terms of higher education, more regular exercise, and higher intakes of energy and fruits and vegetables. Thus, we adjusted for major potential confounders in our analyses. Third, the item ‘nuts’ in the SQFFQ used in this study cannot represent all nuts, because it only included peanuts, pine nuts, and almonds. For this reason, direct comparisons with the results of other studies may be difficult. Fourth, hospital controls who voluntarily participate in studies such as ours may be more likely to have a healthier lifestyle compared with cancer patients. For comparability, we recruited cases and controls in the same hospital, and adjusted for factors that were different between groups. Fifth, because of the case-control study design, recall bias is an inherent weakness. It is known that people who are conscious of health may over-report or under-report some food items [52]. However, the protective effect of nuts on colorectal cancer was not generally known at the time of the survey and thus should be unrelated to recall bias. Finally, due to the small number of participants in the highest nut consumption category, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of our results are due to chance. However, the associations were consistent in both the sub-site analyses and analyses stratified by sex, which reduces the likelihood of chance findings.

Our study had a retrospective design, which is regarded to have a lower value in terms of evidence hierarchy compared with prospective studies. Nevertheless, case-control studies can provide evidence supporting the general relationship between diet and cancer, while currently available prospective studies lack sufficient duration of follow-up for cancer occurrence. Our results do need to be confirmed in a large cohort study with an appropriate dietary assessment of nut consumption.

Conclusions

In conclusion, high frequency of nut consumption appears to play a role in decreasing colorectal cancer risk in this study of a Korean population. Our findings could be used to advise the general public about nut consumption.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- SQFFQ:

-

Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

References

Nuts & Dried Fruits. Global Statistical Review 2015/2016.

Korea Health Statistics 2015 : Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-3) Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Blomhoff R, Carlsen MH, Andersen LF, Jacobs DR, Jr. Health benefits of nuts: potential role of antioxidants. Br J Nutr 2006, 96 Suppl 2:S52–S60.

Brufau G, Boatella J, Rafecas M. Nuts: source of energy and macronutrients. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(Suppl 2):S24–8.

Ros E, Mataix J. Fatty acid composition of nuts--implications for cardiovascular health. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(Suppl 2):S29–35.

Segura R, Javierre C, Lizarraga MA, Ros E. Other relevant components of nuts: phytosterols, folate and minerals. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(Suppl 2):S36–44.

Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2:652–82.

Ros E, Tapsell LC, Sabate J. Nuts and berries for heart health. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12:397–406.

Bao Y, Han J, Hu FB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Fuchs CS. Association of nut consumption with total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2001–11.

Eslamparast T, Sharafkhah M, Poustchi H, Hashemian M, Dawsey SM, Freedman ND, Boffetta P, Abnet CC, Etemadi A, Pourshams A, et al. Nut consumption and total and cause-specific mortality: results from the Golestan cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:75–85.

Wu L, Wang Z, Zhu J, Murad AL, Prokop LJ, Murad MH. Nut consumption and risk of cancer and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:409–25.

Zhou D, Yu H, He F, Reilly KH, Zhang J, Li S, Zhang T, Wang B, Ding Y, Xi B. Nut consumption in relation to cardiovascular disease risk and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:270–7.

Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Liu S, Willett WC, Hu FB. Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA. 2002;288:2554–60.

Pan A, Sun Q, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Walnut consumption is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes in women. J Nutr. 2013;143:512–8.

Fernandez-Montero A, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beunza JJ, Barrio-Lopez MT, De la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Moreno-Galarraga L, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Nut consumption and incidence of metabolic syndrome after 6-year follow-up: the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra, University of Navarra follow-up) cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:2064–72.

Kannamkumarath SS, Wrobel K, Wrobel K, Vonderheide A, Caruso JA. HPLC-ICP-MS determination of selenium distribution and speciation in different types of nut. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2002;373:454–60.

Gonzalez CA, Salas-Salvado J. The potential of nuts in the prevention of cancer. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(Suppl 2):S87–94.

Kris-Etherton PM, Hecker KD, Bonanome A, Coval SM, Binkoski AE, Hilpert KF, Griel AE, Etherton TD. Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 9B):71s–88s.

Nagel JM, Brinkoetter M, Magkos F, Liu X, Chamberland JP, Shah S, Zhou J, Blackburn G, Mantzoros CS. Dietary walnuts inhibit colorectal cancer growth in mice by suppressing angiogenesis. Nutrition. 2012;28:67–75.

Yang M, Hu FB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, Wu K, Bao Y. Nut consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:333–7.

Singh PN, Fraser GE. Dietary risk factors for colon cancer in a low-risk population. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:761–74.

Jenab M, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Norat T, Casagrande C, Overad K, Olsen A, Stripp C, Tjonneland A, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Association of nut and seed intake with colorectal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:1595–603.

Yeh CC, You SL, Chen CJ, Sung FC. Peanut consumption and reduced risk of colorectal cancer in women: a prospective study in Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:222–7.

Pickle LW, Greene MH, Ziegler RG, Toledo A, Hoover R, Lynch HT, Fraumeni JF Jr. Colorectal cancer in rural Nebraska. Cancer Res. 1984;44:363–9.

Kune S, Kune GA, Watson LF. Case-control study of dietary etiological factors: the Melbourne colorectal cancer study. Nutr Cancer. 1987;9:21–42.

Peters RK, Pike MC, Garabrant D, Mack TM. Diet and colon cancer in Los Angeles County, California. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3:457–73.

Ahn Y, Kwon E, Shim JE, Park MK, Joo Y, Kimm K, Park C, Kim DH. Validation and reproducibility of food frequency questionnaire for Korean genome epidemiologic study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:1435–41.

International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. World health. Organization. 2004;1

Han C, Shin A, Lee J, Lee J, Park JW, Oh JH, Kim J. Dietary calcium intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:966.

Chun YJ, Sohn SK, Song HK, Lee SM, Youn YH, Lee S, Park H. Associations of colorectal cancer incidence with nutrient and food group intakes in korean adults: a case-control study. Clin Nutr Res. 2015;4:110–23.

Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Wu K, Rosner B, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Comparison of risk factors for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:433–42.

Hjartaker A, Aagnes B, Robsahm TE, Langseth H, Bray F, Larsen IK. Subsite-specific dietary risk factors for colorectal cancer: a review of cohort studies. J Oncol. 2013;2013:703854.

Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:594–602.

Sicherer SH, Furlong TJ, Maes HH, Desnick RJ, Sampson HA, Gelb BD. Genetics of peanut allergy: a twin study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:53–6.

Shek LP, Cabrera-Morales EA, Soh SE, Gerez I, Ng PZ, Yi FC, Ma S, Lee BW. A population-based questionnaire survey on the prevalence of peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergy in 2 Asian populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:324–31. 331.e321–327

Awad AB, Hernandez AY, Fink CS, Mendel SL. Effect of dietary phytosterols on cell proliferation and protein kinase C activity in rat colonic mucosa. Nutr Cancer. 1997;27:210–5.

Awad AB, Chan KC, Downie AC, Fink CS. Peanuts as a source of beta-sitosterol, a sterol with anticancer properties. Nutr Cancer. 2000;36:238–41.

Arya SS, Salve AR, Chauhan S. Peanuts as functional food: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:31–41.

Woyengo TA, Ramprasath VR, Jones PJ. Anticancer effects of phytosterols. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:813–20.

Carter LG, D'Orazio JA, Pearson KJ. Resveratrol and cancer: focus on in vivo evidence. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R209–25.

Flores-Mateo G, Rojas-Rueda D, Basora J, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J. Nut intake and adiposity: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1346–55.

Jackson CL, Hu FB. Long-term associations of nut consumption with body weight and obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(Suppl 1):408s–11s.

Mohammadifard N, Yazdekhasti N, Stangl GI, Sarrafzadegan N. Inverse association between the frequency of nut consumption and obesity among Iranian population: Isfahan healthy heart program. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:925–31.

Villegas R, Gao YT, Yang G, Li HL, Elasy TA, Zheng W, Shu XO. Legume and soy food intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the shanghai Women's health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:162–7.

Asghari G, Ghorbani Z, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Nut consumption is associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes: the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:18–24.

Chukwumah Y, Walker L, Vogler B, Verghese M. Changes in the phytochemical composition and profile of raw, boiled, and roasted peanuts. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9266–73.

Schlormann W, Birringer M, Bohm V, Lober K, Jahreis G, Lorkowski S, Muller AK, Schone F, Glei M. Influence of roasting conditions on health-related compounds in different nuts. Food Chem. 2015;180:77–85.

Aranceta J, Perez Rodrigo C, Naska A, Vadillo VR, Trichopoulou A. Nut consumption in Spain and other countries. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(Suppl 2):S3–11.

King JC, Blumberg J, Ingwersen L, Jenab M, Tucker KL. Tree nuts and peanuts as components of a healthy diet. J Nutr 2008, 138:1736s–1740s.

O'Neil CE, Keast DR, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Nicklas TA. Tree nut consumption improves nutrient intake and diet quality in US adults: an analysis of National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999-2004. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19:142–50.

O'Neil CE, Keast DR, Nicklas TA, Fulgoni VL 3rd. Out-of-hand nut consumption is associated with improved nutrient intake and health risk markers in US children and adults: National Health and nutrition examination survey 1999-2004. Nutr Res. 2012;32:185–94.

Mannisto S, Pietinen P, Virtanen M, Kataja V, Uusitupa M. Diet and the risk of breast cancer in a case-control study: does the threat of disease have an influence on recall bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:429–39.

Acknowledgements

English language editing was provided by Mrs. Bethanie Rammer, BioMedEdits, United States.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, No. 2010–0010276 and No. 2013R1A1A2A10008260; and the National Cancer Center, Korea, No. 0910220 and No. 1210141.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset and statistical code are available from the corresponding authors: shinaesun@snu.ac.kr and jskim@ncc.re.kr.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS and JK contributed equally to this manuscript and are considered to be co-corresponding authors; JL performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; AS and JK provided advice on the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript; AS, JK, JHO conceived of the study and reviewed, guided, and edited the manuscript; all authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants were given a detailed description of the study, and written informed consent was collected from all participants. The present study guidelines were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center (IRB No. NCCNCS-10-350 and NCC 2015-0202).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Shin, A., Oh, J.H. et al. The relationship between nut intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a case control study. Nutr J 17, 37 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0345-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0345-y