Abstract

Background

Higher meat and protein intakes have been associated with increased body weight in adults, but studies evaluating body composition are scarce. Furthermore, our knowledge in adolescents is limited. This study aimed to investigate the prospective associations of intakes of different meat types, and their respective protein contents during childhood, with body composition during adolescence.

Methods

Dietary (using food frequency questionnaires) and body composition (measured by bioelectrical impedance) data were collected from the 10- and 15-year follow-up assessments respectively, of the GINIplus and LISAplus birth cohort studies. Sex-stratified prospective associations of meat and meat protein intakes (total, processed, red meat and poultry) with fat mass index (FMI) and fat free mass index (FFMI), were assessed by linear regression models (N = 1610).

Results

Among males, higher poultry intakes at age 10 years were associated with a higher FMI at age 15 years [β = 0.278 (SE = 0.139), p = 0.046]; while higher intakes of total and red meat were prospectively associated with higher FFMI [0.386 (0.143), p = 0.007, and 0.333 (0.145), p = 0.022, respectively]. Additionally in males, protein was associated with FFMI for total and red meat [0.285 (0.145) and 0.356 (0.144), respectively].

Conclusions

Prospective associations of meat consumption with subsequent body composition in adolescents may differ by sex and meat source.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Concerns regarding excessive meat intake include increased risks of all-cause mortality [1], cancer [2], CVD [3] and diabetes mellitus [4]. Observational studies have also associated high meat intakes with increased risk of weight gain and obesity [5]. Red and processed meats in particular, have been associated with increased weight gain. However, meat types are very diverse, and differ substantially from each other in terms of macronutrient and energy composition as well as processing. A number of observational studies have reported animal protein, the main macronutrient component of meat, to be directly associated with weight gain [6]. On the other hand, animal protein is known to increase satiety and thermogenesis [7], and intervention studies have reported beneficial effects of high protein diets on fat loss and weight maintenance [8]. Amino acids obtained from meat protein have been proposed to exert an anabolic effect on muscle mass, and may be important in the development and maintenance of lean tissue [9]. It is hence possible that the associations reported between meat intake and weight gain in observational studies could be due to gains in lean mass rather than fat mass. Indeed, positive prospective associations between animal protein intake and lean body mass from puberty to young adulthood have been reported in females [10].

A better understanding of the role of different meat types and their respective protein contents is needed in order to shed light on the underlying factors driving associations between meat intake and weight gain. Furthermore, the evaluation of body composition can determine whether weight gains associated with meat intake are a result of accumulating fat mass, fat-free mass, or both. Hence, in order to appreciate the true role of meat intake in adiposity, accurate body composition data are necessary.

In a large proportion of German adolescents, meat intakes exceed recommended amounts [11], and the prevalence of overweight and obesity is high and rising further [12]. Considering that overweight in adolescence is known to track into adulthood [13], the identification of meat as a contributor towards increased fat mass in adolescence could have important implications for the early prevention of overweight and associated comorbidities. There is a need for longitudinal studies on the association between meat intake and body composition during adolescence, a critical life stage during which fast weight-gain occurs [14]. The aims of the present study were thus to investigate prospective associations of the consumption of different sources of meat and meat-protein during childhood, with fat mass and fat-free mass during adolescence.

Methods

Subjects

The present study used data from the 10- and 15-year follow-up assessments of the ongoing GINIplus (German Infant Nutritional Intervention plus environmental and genetic influences on allergy development) and LISAplus (Influence of Lifestyle-Related Factors on the Immune System and the Development of Allergies in Childhood plus the Influence of Traffic Emissions and Genetics) birth cohort studies. Healthy full-term new-borns were recruited from obstetric clinics within four German cities between 1995 and 1999. Information was collected using identical questionnaires and at physical examinations. The study designs, recruitment and exclusion criteria have been described previously [15, 16]. For both studies, approval by the local ethics committees (Bavarian Board of Physicians, University of Leipzig, Board of Physicians of North-Rhine-Westphalia) and written consent from participant’s families were obtained.

Exposure variables

Dietary intake data was obtained from the 10-year follow-up assessment, using a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), designed and validated to assess food and nutrient intake over the past year in school-aged children [17]. In brief, subjects were asked to report estimated frequency and portion size of intakes of 80 food items. A quality control procedure was applied based on recommendations by Willett et al. for data cleaning in nutritional epidemiology [18].

Four meat types were defined: processed meat (salami, liver sausage, cold meat, bratwurst and wiener- or pork-sausage), red meat (pork, beef, veal), poultry (any poultry meat) and other meats (offal and ready meals with meat). The protein content (g/day) of each of the different meat types was calculated based on the German Food Code and Nutrient Database (BLS) version II.3.1 [19], and converted to kcal/d (g/d multiplied by 4). The daily intakes (mg/d) of essential amino acids (EAA), saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) were also obtained from the FFQ by use of the same database. Total meat intake (the sum of all meat types) and each individual meat type, as well as their respective protein contents, were included as exposures in the statistical analyses. The food-group “other meats” was rarely consumed and was not individually analysed.

Outcome variables

Measures of fat mass and fat free mass were obtained during the 15-year physical examination by means of phase sensitive bioelectrical impedance (BIA). Fat mass index (FMI) and fat-free mass index (FFMI) were calculated by dividing fat mass and fat-free mass (kg), respectively, by height squared (kg/m2) measured without shoes at the same examination. Blood samples were also obtained from willing participants during the 10- and 15-year follow-up physical examinations. The concentrations (mmol/L) of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides (TAG) were measured in serum using homogenous enzymatic colorimetric methods on a Modular Analytics System from Roche Diagnostics GmbH Mannheim according to the manufactures instructions. External controls were used in accordance with the guidelines of the German Society of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. The ratio of total to HDL cholesterol (TOTAL:HDL) was calculated by dividing total cholesterol by HDL.

Adjustment variables

Statistical models were adjusted for study (GINI observation arm; GINI intervention arm; LISA), recruitment region (Munich; Wesel; Bad Honnef; Leipzig), parental education level (highest level achieved by mother or father: ≤10thgrade = low/medium; >10thgrade = high), exact age at BIA measurement (years), sedentary behaviour at age 15 years (≤2 h screen time/day = low; > 2 h screen time/day = high), pubertal onset (any presence of acne or spots, pubic or axillary hair, breast development, menstruation, penis or testicle enlargement at age 10 years: yes; no), and weight category at age 10 years (BMI z-score ≤ 1 = normal weight; BMI z-score > 1 = overweight). BMI z-scores used to categorize body weight were calculated according to the 2007 BMI-for-age WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents [20]. Due to non-random loss-to follow-up, children with low parental education were underrepresented in our study population (Additional file 1: Table S1), therefore low (<10thgrade) and medium (10thgrade) parental education were combined into low/medium.

Statistical analysis

Subjects providing complete data for outcome, exposure and adjustment variables, were included (N = 1736). Participants were excluded if they reported an illness affecting diet at 10 or 15 years (e.g. diabetes, anorexia, coeliac disease, cancer) or medical dietary indications, such as gluten-free or lactose-free diets, at age 15 years (n = 82). Clear outliers in outcomes (n = 2) and exposures (n = 42) were visually identified using descriptive plots and excluded from the analyses (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Meat and meat protein intake variables were adjusted for daily caloric intake using the nutrient residual model. For this we computed sex-specific residuals from a regression model where meat and protein variables (kcal/day) were regressed on energy intake (kcal/day) at age 10 years. As these residuals are uncorrelated with total energy intake the variation due to the nutrient composition of the diet, rather than the combination with total amount of food, can be evaluated. Due to non-linearity, residuals were categorized into sex-specific tertiles (T1 = low, T2 = medium and T3 = high intake).

Main subject characteristics for the total study population, and stratified by energy-adjusted meat intake tertiles, were described by medians (25th percentile; 75th percentile) or counts (%). Differences between meat intake tertiles were tested using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2-test for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed and presented stratified by sex. Prospective associations of consumption of meat (total meat, processed, red meat, poultry) and meat protein (total meat protein, processed meat protein, red meat protein, poultry protein) at age 10 years with FMI and FFMI at age 15 years, were assessed by linear regression models. First, minimally adjusted models (MIN) were fit, adjusting for study, recruitment region, parental education level, pubertal onset, age at BIA measurement and sedentary behaviour. As significant associations between meat intake and BMI at age 10 years have been previously reported [21], main models (MAIN) were fit separately, further adjusting for weight category at age 10 years. We performed additional analyses where we further adjusted the main model for EAA, SFA, MUFA or PUFA, respectively. These variables were included in the model as energy-adjusted residuals (computed as described above for meat and protein residuals). We also tested for possible interactions by including an interaction term between the meat or protein exposures and weight category, following which stratified analyses (normal weight; overweight) were performed. Finally, we repeated our main analyses using blood lipid parameters as secondary outcomes in a subgroup of the study population who provided measurements at ages 10 and 15 years (n = 1309). Linear regression models were used to assess the prospective associations of consumption of meat and meat protein at age 10 years with changes in blood lipids (∆LDL, ∆HDL, ∆TAG and ∆TOTAL:HDL) from age 10 to 15 years. Models were adjusted as in the previously described main model, with further adjustment for the respective blood lipid measurement at age 10 years.

Results are presented as β-coefficients (β), along with their standard errors (SE) with reference to the lowest intake tertile (T1). Meat intake residual coefficients have an isocaloric substitution interpretation. A two-sided α-level of 5% was considered significant. For the stratified analyses, we corrected for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction, yielding a corrected two-sided alpha level of 0.025 (0.05/2 = 0.025). Since the meat group “poultry” was composed by only one food item (poultry meat), each poultry tertile includes the same subjects as its respective poultry protein tertile; therefore, the calculated regression coefficients for poultry are identical for both meat and meat protein intakes and are hence only reported when referring to meat intakes. All analyses were conducted using R (www.r-project.org), version 3.2.2 [22].

Results

Study population

Data from 1610 participants (797 females and 813 males) were included in the analyses (Figure S1). Descriptive characteristics are displayed in Table 1. At age 10 years, 16.7% females and 22.5% males were overweight according to WHO cut-off criteria (10.3 and 10.8%, respectively, according to IOTF cut-offs [23]). Children in the highest meat intake tertile were significantly more likely to be overweight at age 10 years. Most children in the study population were from Munich and from families with high parental education.

Regression analyses

Primary outcomes (FMI and FFMI)

Results of the minimally adjusted (MIN) and main (MAIN) linear regression models are presented in Table 2. In females, the MIN models showed that high (T3) total meat and poultry intakes at age 10 years were related to higher FMI at 15 years (p-value for linear trend = 0.006 and 0.019, respectively). These associations were no longer significant in the MAIN models. Similar results were observed for protein intakes in females. In males, the MIN models indicated that high (T3) poultry intakes at age 10 years were associated with higher FMI at age 15 years, and high (T3) red and processed meat intakes were related to higher FFMI; while high (T3) total meat intakes were related to both higher FMI and higher FFMI. Following further adjustment for BMI category in the MAIN model, high (T3) poultry intake at age 10 years remained significantly associated with higher FMI at age 15 years [0.278 (0.139)] (p-value for linear trend = 0.047), while high (T3) total and red meat intakes at age 10 years were significantly associated with higher FFMI at age 15 years [0.386 (0.143) and 0.333 (0.145), respectively] (p-value for linear trend = 0.007 and 0.022, respectively). Similar associations were observed with the respective protein intakes of all meat types [0.285 (0.145) for high total meat protein with higher FFMI, and 0.356 (0.144) for high red meat protein with higher FFMI].

Results from the further adjusted models (adjusted for EAA, SFA, MUFA or PUFA) are presented in Additional file 3: Tables S3a for females and S3b for males. In females, additional adjustment for MUFA or PUFA resulted in significant positive associations between high (T3) total meat and meat protein intakes with FMI. When adjusting for PUFA, high (T3) poultry intakes were also significantly associated with FMI. In males, when adjusting for EAA, SFA, MUFA or PUFA, the association between high poultry intake and FMI no longer reached statistical significance (except with adjustment for MUFA, where it was weakened but remained borderline significant). The associations between red meat, total meat protein and red meat protein with FFMI in males were no longer significant following adjustment for EAA, while the association of total meat with FFMI was weakened. On the other hand, when adjusting for SFA, an additional positive association was observed between high (T3) processed meat and FFMI. When adjusting for MUFA or PUFA, the association between total meat protein intakes with FFMI was no longer significant.

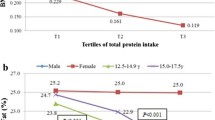

Stratified analyses (normal weight/ overweight)

Stratified analyses results are presented in Fig. 1 (exact values in Additional file 4: Tables S2a for females and S2b for males). In females, high (T3) intakes of poultry in children with normal weight at age 10 years were related to higher FMI at age 15 years [0.314 (0.125)]. In males high (T3) total meat intakes in normal weight children at age 10 years was related to higher FFMI at age 15 years [0.350 (0.150)].

Secondary outcomes (∆LDL, ∆HDL, ∆TAG and ∆TOTAL:HDL)

Blood samples at both age 10 and 15 years were available in a subsample of 1309 participants (636 females and 673 males). In males, high (T3) red meat and red meat protein intakes were associated with increasing TAG concentrations [0.131 (0.060), p-value = 0.030; and 0.130 (0.060), p-value = 0.031, respectively]. No significant associations were observed for any of the meat or meat protein types with the other blood lipid parameters (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study aimed at assessing the associations of meat intake at the age of 10 years with later body composition during adolescence, and to determine the role of protein in such associations. Our findings suggest that a higher poultry intake during childhood in males may lead to an accumulation of body fat during adolescence. This finding is in line with the notion that higher meat intakes promote increased weight gain, proposed in a number of observational studies [5]. Amongst these, Vergnaud et al. [24] have highlighted poultry as a possible determinant of gains in weight and waist circumference in adults. Contrary to other observational studies [5], our results suggest a beneficial association between the consumption of red meats and later lean body mass in adolescent males.

Two major differences between our and many other existing observational studies should be noted. Firstly, studies on the association of meat intake with overweight typically describe changes in body weight or BMI. These measures cannot indicate possible variation in body composition. Hence, gains in BMI or body weight are not analogous to gains in body fat, and without supporting information cannot be interpreted as such. Secondly, most studies reporting associations of different meat types with overweight have been carried out in adults. Our study population consisted of children assessed over a five-year follow-up period during adolescence, from ages 10 to 15 years. We have previously reported cross-sectional associations between higher total meat intakes and increased BMI in 10-year old children from the GINIplus and LISAplus birth cohort studies [21]. Additionally, Bradlee et al. [25] reported that adolescent boys (aged 12–16) with smaller waist circumferences tended to eat less meat. Nevertheless, in view of the present study findings, it could be suggested that associations between red meat and weight gain in adolescents may reflect increased lean mass rather than fat mass in males. Additional analyses indicated that associations between total meat and FFMI were stronger in lean than in overweight subjects. This suggests that the development of lean tissue triggered by higher meat intakes occurs more readily in leaner males, although it is possible that due to the smaller number of overweight individuals, there was not sufficient power for associations in this group to reach statistical significance.

Our data indicated that the subsequent increase in lean mass observed following higher red meat intakes could be attributed to the high protein content of this meat type. These findings are not unexpected, considering that red meat protein is a rich source of essential amino acids, known to be important for the development and preservation of lean tissue [9]. Indeed, when further adjusting our analyses for dietary EAA, the associations between red meat and red meat protein with FFMI in males were no longer significant. This was not the case when adjusting for other nutrients, suggesting that EAA might be a potentially responsible component in the association of red meat with lean body mass. Our findings are consistent with intervention studies which propose that higher protein intakes contribute towards increasing lean tissue, and can be beneficial for weight loss and maintenance [26]. Most observational studies however, fail to reproduce these findings longitudinally. Some studies even propose a detrimental effect of protein, in particular animal protein, on weight gain [27]. However, measurements of body composition are also scarce in these studies. A Danish study did report that the energy intake from protein was positively related to total fat mass in 36-year-old men and women [28]. On the other hand, a prospective relation between animal protein intake during puberty and FFMI in young adulthood was reported among females (and also in males when adjusting for FMI) [10]. Furthermore, in another study, higher protein was prospectively associated with higher FFMI in overweight and lower FMI in lean girls aged 8–10 years [29]. It is however of note that despite the greater lean mass observed in males in the present study, our secondary analyses also revealed an association of red meat and red meat protein with increasing TAG levels in males. This finding supports prospective studies which have reported a link between red meat and CVD [3, 30]. Attempts to explain positive associations between meat intake and blood lipids often refer to the high SFA content of meat as the responsible component [31]. Studies have also indicated that the consumption of lean meat (low in SFA) could have beneficial effects on cardio-metabolic risk markers [32]. Nevertheless, in our analyses, adjustment for SFA did not alter the observed association between red meat and TAG (data not shown). Further research is warranted in order to evaluate the specific role of lean meat on blood lipids in adolescence. Until this area is better understood, it is unclear whether all red meats represent a healthy dietary protein source for adolescents attempting to promote lean body mass development. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that other dietary components consumed in the dietary pattern along with red meat, could have contributed to its observed association with lean body mass. Unfortunately, we were not able to look at the separate role of protein intake in the association of poultry with FMI, which would have been interesting considering it promotes changes in body composition which oppose those of red meats. Adjusting for EAA, SFA or PUFA weakened the association of poultry with FMI in males, whilst a positive association was observed in females with adjustment for PUFA. These results reflect a complex, sex-specific role of this meat subtype in fat mass accumulation, which, from the present analyses cannot be attributed to any specific nutrient.

We highlight that the present study was carried out during adolescence, a period where growth occurs at its most rapid rate since infancy, and where significant weight gain and important changes in body composition take place [14]. Furthermore our findings were limited to males, who, under the influence of testosterone, at this stage undergo a significant increase in lean body tissue [14]. This process could be enhanced by higher protein intakes; however it has been suggested that increasing protein consumption is not entirely necessary to maintain nitrogen retention, due to an increased efficiency of protein utilization at this life-stage [33]. It is hence plausible that the metabolic response to meat intake in adolescents is different to that occurring in adults [14]. Considering the evidence for increased risk of disease associated with red and processed meat in particular [2], these findings should be interpreted with caution, keeping in mind that similar findings are not necessarily expected to be observed in adults.

A major strength of the present study is that it is based on data from two large population-based birth cohorts. The large sample size allows for robust prospective analyses, lacking thus far in observational studies concerning meat consumption and body composition. Our data allows us to evaluate specific associations of meat consumption with fat and lean body mass. Although we additionally assessed associations with changes in blood lipids, we were unfortunately not able to assess blood biomarkers of obesity such as adipokines, which would have provided further insight into the biological effects of meat intake in parallel to those reflected by our anthropometric measurements. Additionally, some other limitations were also encountered. Although study sampling was primarily population-based, non-random loss-to-follow-up, often occurring in cohort studies, meant children of lower social classes were underrepresented in the present analyses, and hence findings cannot be considered representative of the study area. Furthermore, the 10-year FFQ was completed by parents alongside their children, as young children might have difficulties recalling intakes or understanding portion sizes. Nevertheless, the questionnaire produced plausible values in terms of energy intake and any misreporting was most likely detected through extensive quality control. The improved quality of the data was obtained at the expense of reducing the sample size, although the study sample remained large with no substantial loss of power. The FFQ lacks questions regarding typically vegetarian protein sources such as tofu or pulses. Therefore, the relative caloric contribution of meat intake – as used in this study – could be overestimated among children whose diets are high in vegetable protein. When excluding children following a meat-free diet at age 10 years, our results remained consistent (data not shown).

Conclusions

In conclusion, prospective associations of meat consumption with subsequent body composition in adolescents may differ by sex and meat source. We found that in males high poultry intake is prospectively associated with increased fat mass, while red meat in males is related to higher fat free mass. Protein from red meat likely plays a major role in its association with lean mass. These findings provide important insight into the underlying changes in body composition occurring with meat and meat protein intakes during the period of pubertal development.

Abbreviations

- FFMI:

-

Fat free mass index

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- FMI:

-

Fat mass index

References

Sinha R, Cross AJ, Graubard BI, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A. Meat intake and mortality: a prospective study of over half a million people. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):562–71.

Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1599–1600.

Abete I, Romaguera D, Vieira AR, Lopez de Munain A, Norat T. Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(5):762–75.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2271–83.

Rouhani MH, Salehi-Abargouei A, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. Is there a relationship between red or processed meat intake and obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev. 2014;15(9):740–8.

Halkjaer J, Olsen A, Overvad K, Jakobsen MU, Boeing H, Buijsse B, Palli D, Tognon G, Du H, van der AD, et al. Intake of total, animal and plant protein and subsequent changes in weight or waist circumference in European men and women: the Diogenes project. Int J Obes (2005). 2011;35(8):1104–13.

Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1558s–61.

Clifton PM, Condo D, Keogh JB. Long term weight maintenance after advice to consume low carbohydrate, higher protein diets--a systematic review and meta analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(3):224–35.

Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, Langkamp-Henken B. Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):260–74.

Assmann KE, Joslowski G, Buyken AE, Cheng G, Remer T, Kroke A, Gunther AL. Prospective association of protein intake during puberty with body composition in young adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2013;21(12):E782–9.

Mensink GBM, Richter A, Vohmann C, Stahl A, Six J, Kohler S, Fischer J, Heseker H. EsKiMo. The nutrition module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Ernährung - Wissenschaft und Praxis. 2007;1(5):225–9.

Bibiloni Mdel M, Pons A, Tur JA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents: a systematic review. ISRN Obes. 2013;2013:392747.

Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95–107.

Rogol AD, Roemmich JN, Clark PA. Growth at puberty. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(6 Suppl):192–200.

Berg A, Kramer U, Link E, Bollrath C, Heinrich J, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Grubl A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Wichmann HE, et al. Impact of early feeding on childhood eczema: development after nutritional intervention compared with the natural course - the GINIplus study up to the age of 6 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(4):627–36.

Heinrich J, Bolte G, Holscher B, Douwes J, Lehmann I, Fahlbusch B, Bischof W, Weiss M, Borte M, Wichmann HE. Allergens and endotoxin on mothers’ mattresses and total immunoglobulin E in cord blood of neonates. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(3):617–23.

Stiegler P, Sausenthaler S, Buyken AE, Rzehak P, Czech D, Linseisen J, Kroke A, Gedrich K, Robertson C, Heinrich J. A new FFQ designed to measure the intake of fatty acids and antioxidants in children. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(1):38–46.

Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. USA: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Hartmann BM, Bell S, Va’squez-Caiquedo AL. Der Bundeslebensmittelschlüssel. German Nutrient DataBase. Karlsruhe: Federal Research Centre for Nutrition and Food (BfEL); 2005.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–7.

Pei Z, Flexeder C, Fuertes E, Standl M, Buyken A, Berdel D, von Berg A, Lehmann I, Schaaf B, Heinrich J. Food intake and overweight in school-aged children in Germany: results of the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64(1):60–70.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2000;320(7244):1240.

Vergnaud AC, Norat T, Romaguera D, Mouw T, May AM, Travier N, Luan J, Wareham N, Slimani N, Rinaldi S, et al. Meat consumption and prospective weight change in participants of the EPIC-PANACEA study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(2):398–407.

Bradlee ML, Singer MR, Qureshi MM, Moore LL. Food group intake and central obesity among children and adolescents in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(6):797–805.

Clifton P. Effects of a high protein diet on body weight and comorbidities associated with obesity. Br J Nutr. 2012;108 Suppl 2:S122–9.

Bujnowski D, Xun P, Daviglus ML, Van Horn L, He K, Stamler J. Longitudinal association between animal and vegetable protein intake and obesity among men in the United States: the Chicago Western Electric Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1150–5. e1151.

Koppes LL, Boon N, Nooyens AC, van Mechelen W, Saris WH. Macronutrient distribution over a period of 23 years in relation to energy intake and body fatness. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(1):108–15.

van Vught AJ, Heitmann BL, Nieuwenhuizen AG, Veldhorst MA, Brummer RJ, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Association between dietary protein and change in body composition among children (EYHS). Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2009;28(6):684–8.

Snowdon DA, Phillips RL, Fraser GE. Meat consumption and fatal ischemic heart disease. Prev Med. 1984;13(5):490–500.

Li D, Sinclair A, Mann N, Turner A, Ball M, Kelly F, Abedin L, Wilson A. The association of diet and thrombotic risk factors in healthy male vegetarians and meat-eaters. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53(8):612–9.

Li D, Siriamornpun S, Wahlqvist ML, Mann NJ, Sinclair AJ. Lean meat and heart health. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2005;14(2):113–9.

Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Elalaily R. Nutrition and pubertal development. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18 Suppl 1:S39–47.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the families for their participation in the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. Furthermore, we thank all members of the GINIplus and LISAplus Study Groups for their excellent work. The GINIplus Study group consists of the following: Institute of Epidemiology I, Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg (Heinrich J, Brüske I, Schulz H, Flexeder C, Zeller C, Standl M, Schnappinger M, Sußmann M, Thiering E, Tiesler C); Department of Pediatrics, Marien-Hospital, Wesel (Berdel D, von Berg A); Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich, Dr von Hauner Children’s Hospital (Koletzko S); Child and Adolescent Medicine, University Hospital rechts der Isar of the Technical University Munich (Bauer CP, Hoffmann U); IUF- Environmental Health Research Institute, Düsseldorf (Hoffmann B, Link E, Klümper C).

The LISAplus Study group consists of the following: Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Institute of Epidemiology I, Munich (Heinrich J, Schnappinger M, Brüske I, Sußmann M, Lohr W, Schulz H, Zeller C, Standl M); Department of Pediatrics, Municipal Hospital “St. Georg”, Leipzig (Borte M, Gnodtke E); Marien Hospital Wesel, Department of Pediatrics, Wesel (von Berg A, Berdel D, Stiers G, Maas B); Pediatric Practice, Bad Honnef (Schaaf B); Helmholtz Centre of Environmental Research – UFZ, Department of Environmental Immunology/Core Facility Studies, Leipzig (Lehmann I, Bauer M, Röder S, Schilde M, Nowak M, Herberth G , Müller J, Hain A); Technical University Munich, Department of Pediatrics, Munich (Hoffmann U, Paschke M, Marra S); Clinical Research Group Molecular Dermatology, Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Technische Universität München (TUM), Munich (Ollert M).

Funding

The GINIplus study was mainly supported for the first 3 years of the Federal Ministry for Education, Science, Research and Technology (interventional arm) and Helmholtz Zentrum Munich (former GSF) (observational arm). The 4 year, 6 year, 10 year and 15 year follow-up examinations of the GINIplus study were covered from the respective budgets of the 5 study centres (Helmholtz Zentrum Munich (former GSF), Research Institute at Marien-Hospital Wesel, LMU Munich, TU Munich and from 6 years onwards also from IUF - Leibniz Research-Institute for Environmental Medicine at the University of Düsseldorf) and a grant from the Federal Ministry for Environment (IUF Düsseldorf, FKZ 20462296). The LISAplus study was mainly supported by grants from the Federal Ministry for Education, Science, Research and Technology and in addition from Helmholtz Zentrum Munich (former GSF), Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Leipzig, Research Institute at Marien-Hospital Wesel, Pediatric Practice, Bad Honnef for the first 2 years. The 4 year, 6 year, 10 year and 15 year follow-up examinations of the LISAplus study were covered from the respective budgets of the involved partners (Helmholtz Zentrum Munich (former GSF), Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research - UFZ, Leipzig, Research Institute at Marien-Hospital Wesel, Pediatric Practice, Bad Honnef, IUF – Leibniz-Research Institute for Environmental Medicine at the University of Düsseldorf) and in addition by a grant from the Federal Ministry for Environment (IUF Düsseldorf, FKZ 20462296). Further, the 15 year follow-up examination of the GINIplus and LISAplus studies was supported by the Commission of the European Communities, the 7th Framework Program: MeDALL project. The 15 year follow-up examination of the GINIplus study was additionally supported l by the Mead Johnson and Nestlé companies. The work of BK is financially supported in part by the European Research Council Advanced Grant META-GROWTH (ERC-2012-AdG – no.322605).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the ongoing nature of the GINIplus and LISAplus studies.

Authors’ contributions

CH and MS were involved in the conception and design of the study; AvB, DB, IL, BH, SK, and JH in the data acquisition; CH and MS in the statistical analyses; CH, MS, BK and AB in the interpretation; CH drafted the manuscript; all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

For both studies, approval by the local ethics committees (Bavarian Board of Physicians, University of Leipzig, Board of Physicians of North-Rhine-Westphalia) and written consent from participant’s families were obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison of lost-to-follow-up and not-lost-to-follow-up study participants. (PDF 173 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Study participants. (PDF 84 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3a.

Prospective association of tertiles of meat and meat protein intakes with FMI and FFMI in females (n = 636) adjusted for EAA, SFA, MUFA or PUFA. Table S3b. Prospective association of tertiles of meat and meat protein intakes with FMI and FFMI in males (n = 673) adjusted for EAA, SFA, MUFA or PUFA. (PDF 272 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S2a.

Prospective association of tertiles of meat and meat protein intakes (T2 and T3 vs T1) with FMI and FFMI, stratified by BMI at 10y (normal weight/overweight), in females. Table S2b. Prospective association of tertiles of meat and meat protein intakes (T2 and T3 vs T1) with FMI and FFMI, stratified by BMI at 10y (normal weight/overweight), in males. (PDF 248 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, C., Buyken, A., von Berg, A. et al. Prospective associations of meat consumption during childhood with measures of body composition during adolescence: results from the GINIplus and LISAplus birth cohorts. Nutr J 15, 101 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0222-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0222-5